Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

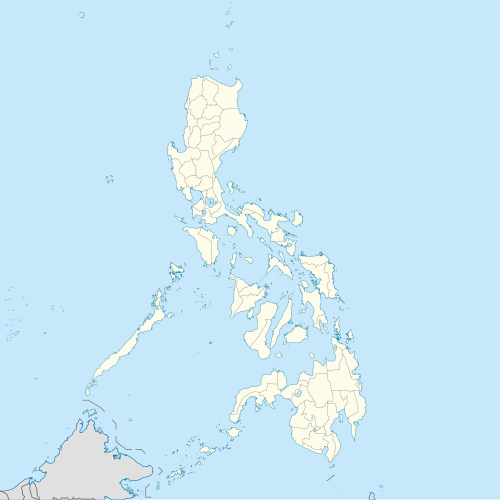

History of the Philippines (900–1565)

View on Wikipedia

| |

| Horizon | Philippine history |

|---|---|

| Geographical range | Southeast Asia |

| Period | c. 900–1560s |

| Dates | c. Before 900 AD |

| Major sites | Tondo, Maynila, Pangasinan, Limestone tombs, Idjang citadels, Panay, Cebu (historical polity), Butuan (historical polity), Sanmalan, Sultanate of Maguindanao, Sultanate of Sulu, Ma-i, Bo-ol, Gold artifacts, Singhapala |

| Characteristics | Indianized kingdoms, Hindu and Buddhist Nations, Malay Sultanates |

| Preceded by | Prehistory of the Philippines |

| Followed by | Colonial era |

The recorded pre-colonial history of the Philippines,[1][2] sometimes also referred to as its "protohistoric period"[1]: 15 begins with the creation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription in 900 AD and ends with the beginning of Spanish colonization in 1565. The inscription on the Laguna Copperplate Inscription itself dates its creation to 822 Saka (900 AD). The creation of this document marks the end of the prehistory of the Philippines at 900 AD, and the formal beginning of its recorded history.[2][3][4] During this historical time period, the Philippine archipelago was home to numerous kingdoms and sultanates and was a part of the Indosphere and Sinosphere.[5]

Sources of precolonial history include archeological findings; records from contact with the Song dynasty, the Brunei Sultanate, Korea, Japan, and Muslim traders; the genealogical records of Muslim rulers; accounts written by Spanish chroniclers in the 16th and 17th centuries; and cultural patterns that at the time had not yet been replaced through European influence.[6]

Societal categories

[edit]Early Philippine society was composed of diverse subgroups such as fishermen, farmers and hunter-gatherers, with some living in mountainside swiddens, some on houseboats and some in commercially developed coastal ports. Some subgroups were economically self-sufficient, and others had symbiotic relationships with neighboring subgroups.[7]: 138 Society can be classified into four categories as follows:[7]: 139

- Classless societies, societies with no terms which distinguish one social class from another;

- Warrior societies, societies with a recognized class distinguished by prowess in battle;

- Petty plutocrats, societies with a recognized class characterized by inherited real property; and

- Principalities, societies with a recognized ruling class with inherited rights to assume political office, or exercise central authority

Social classes

[edit]The fourth societal category above can be termed the datu class, and was a titled aristocracy.[7]: 150–151

The early polities were typically made up of three-tier social structure: a nobility class, a class of "freemen", and a class of dependent debtor-bondsmen:[8][1]

Laguna Copperplate Inscription

[edit]

The Laguna Copperplate Inscription (LCI) is the earliest record of a Philippine language and the presence of writing in the islands.[11] The document measures around 20 cm by 30 cm and is inscribed with ten lines of writing on one side.

Text

[edit]The text of the LCI was mostly written in Old Malay with influences of Sanskrit, Tamil, Old Javanese and Old Tagalog using the Kawi script. Dutch anthropologist Antoon Postma deciphered the text. The date of the inscription is in the "Year of Saka 822, month of Vaisakha", corresponding to April–May in 900 AD.

The text notes the acquittal of all descendants of a certain honorable Namwaran from a debt of 1 kati and 8 suwarna, equivalent to 926.4 grams of gold, granted by the Military Commander of Tundun (Tondo) and witnessed by the leaders of Pailah, Binwangan and Puliran, which are places likely also located in Luzon. The reference to the contemporaneous Medang Kingdom in modern-day Indonesia implies political connections with territories elsewhere in the Maritime Southeast Asia.

Politics

[edit]Emergence of Independent polities

[edit]Early settlements, referred to as barangays, ranged from 20 to 100 families on the coast, and around 150–200 people in more interior areas. Coastal settlements were connected over water, with much less contact occurring between highland and lowland areas.[12] By the 1300s, a number of the large coastal settlements had emerged as trading centers, and became the focal point of societal changes.[8] Some polities had exchanges with other states across Asia.[1][13][14][15][16]

Polities founded in the Philippines from the 10th–16th centuries include Maynila,[17] Tondo, Namayan, Kumintang, Pangasinan, Caboloan, Cebu, Butuan, Maguindanao, Buayan, Lanao, Sulu, and Ma-i.[18] Among the nobility were leaders called datus, responsible for ruling autonomous groups called barangay or dulohan.[8] When these barangays banded together, either to form a larger settlement[8] or a geographically looser alliance group,[1] the more esteemed among them would be recognized as a "paramount datu",[8][19] rajah, or sultan[20] which headed the community state.[21] There is little evidence of large-scale violence in the archipelago prior to the 2nd millennium AD,[22][better source needed] and throughout these periods population density is thought to have been low.[23]

| History of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Other political systems by ethnic group

[edit]

In Luzon

[edit]In the Cagayan Valley, the head of the Ilongot city-states was called a benganganat, while for the Gaddang it was called a mingal.[24][25][26]

The Ilocano people in northwestern Luzon were originally located in modern-day Ilocos Sur and were led by a babacnang. Their polity was called samtoy which did not have a royal family but, rather, was a collection of certain barangays (chiefdoms).

In Mindanao

[edit]The Lumad people from inland Mindanao are known to have been headed by a datu.

The Subanon people in the Zamboanga Peninsula were ruled by a timuay until they were overcome by the Sultanate of Sulu in the 13th century.

The Sama-Bajau people in Sulu who were not Muslims nor affiliated with the Sultanate of Sulu were ruled by a nakurah before the arrival of Islam.

Trade

[edit]Trade with China is believed to have begun during the Tang dynasty, but grew more extensive during the Song dynasty.[27] By the 2nd millennium AD, some Philippine polities were known to have sent trade delegations which participated in the Tributary system enforced by the Chinese imperial court, trading but without direct political or military control.[28][page needed][1] The items much prized in the islands included jars, which were a symbol of wealth throughout South Asia, and later metal, salt and tobacco. In exchange were traded feathers, rhino horns, hornbill beaks, beeswax, bird's-nests, resin, and rattan.

Indian influence

[edit]Indian cultural traits, such as linguistic terms and religious practices, began to spread within the Philippines during the 10th century, likely via the Hindu Majapahit empire.[15][8][29]

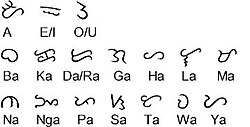

Writing systems

[edit]Brahmic scripts reached the Philippines in the form of the Kawi script, and later the Baybayin writing system.[30] The Laguna Copperplate Inscription was written using the Kawi script.

Baybayin

[edit]

By the 13th or 14th century, the baybayin script was used for the Tagalog language. It spread to Luzon, Mindoro, Palawan, Panay and Leyte, but there is no proof it was used in Mindanao.

There were at least three varieties of baybayin in the late 16th century. These are comparable to different variations of Latin which use slightly different sets of letters and spelling systems.[31][better source needed]

In 1521, the chronicler Antonio Pigafetta from the expedition of Ferdinand Magellan noted that the people that they met in Visayas were not literate. However, in the next few decades the Baybayin script seemed to have been introduced to them. In 1567 Miguel López de Legaspi reported that "they [the Visayans] have their letters and characters like those of the Malays, from whom they learned them; they write them on bamboo bark and palm leaves with a pointed tool, but never is any ancient writing found among them nor word of their origin and arrival in these islands, their customs and rites being preserved by traditions handed down from father to son without any other record."[32]

Earliest documented Chinese contact

[edit]The earliest date suggested for direct Chinese contact with the Philippines was 982. At the time, merchants from "Ma-i" (now thought to be either Bay, Laguna on the shores of Laguna de Bay,[33] or a site called "Mait" in Mindoro[34][35]) brought their wares to Guangzhou and Quanzhou. This was mentioned in the History of Song and Wenxian Tongkao by Ma Duanlin which were authored during the Yuan Dynasty.[34]

Arrival of Islam

[edit]

Beginnings

[edit]

Muslim traders introduced Islam to the then-Indianized Malayan empires around the time that wars over succession had ended in the Majapahit Empire in 1405. Islam in the Philippines had established itself in Simunul, Tawi-Tawi, the oldest mosque in the country. By the 15th century, Islam was established in the Sulu Archipelago and spread from there.[36] Subsequent visits by Arab, Persians, Malay and Javanese missionaries helped spread Islam further in the islands.[citation needed]

the Islamic "Raja" of the Philippines were good at defending the island nations, they often built their own: fleets, outposts, fortifications and ports. The Islamic community often ruled the country from their presence in Manila. Their legitimacy is known through their diplomatic relations that extended from China to India.

At the peak of Islam in the Philippines the Sultanate of Sulu once encompassed parts of modern-day: Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. Their progress is recognized on the maps as evidence of political and military strength.

Spanish expeditions

[edit]This article or section appears to contradict itself on leaders of the expeditions subsequent to Magellen's expedition in 1521. (September 2020) |

The following table summarizes expeditions made by the Spanish to the Philippine archipelago.

| Year | Leader | Ships | Landing |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1521 | Trinidad, San Antonio, Concepcion, Santiago and Victoria | Homonhon, Limasawa, Cebu | |

| 1525 | Santa María de la Victoria, Sancti Spiritus, Anunciada, San Gabriel, Santa María del Parral, San Lesmes, and Santiago | Surigao, Visayas, Mindanao | |

| 1527 | Florida, Santiago, and Espiritu Santo | Mindanao | |

| 1542 | Santiago, Jorge, San Antonio, San Cristóbal, San Martín, and San Juan | Samar, Leyte, Saranggani | |

| 1564 | San Pedro, San Pablo, San Juan and San Lucas | first landed on Samar, established colonies as part of Spanish Empire |

First expedition

[edit]

Although the archipelago may have been visited before by the Portuguese (who conquered Malacca City in 1511 and reached Maluku Islands in 1512),[citation needed] the earliest European expedition to the Philippine archipelago was led by the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan in the service of King Charles I of Spain in 1521.[37]

The Magellan expedition sighted the mountains of Samar at dawn on March 17, 1521, making landfall the following day at the small, uninhabited island of Homonhon at the mouth of Leyte Gulf.[38] On Easter Sunday, March 31, 1521, in the island of Mazaua, Magellan planted a cross on the top of a hill overlooking the sea and claimed the islands he had encountered for the King of Spain, naming them Archipelago of Saint Lazarus as stated in "First Voyage Around The World" by his companion, the chronicler Antonio Pigafetta.[39]

Magellan sought alliances among the people in the islands beginning with Datu Zula of Sugbu (Cebu) and took special pride in converting them to Christianity. Magellan got involved in the political conflicts in the islands and took part in a battle against Lapulapu, chief of Mactan and an enemy of Datu Zula.

At dawn on April 27, 1521, Magellan with 60 armed men and 1,000 Visayan warriors had great difficulty landing on the rocky shore of Mactan where Lapulapu had an army of 1,500 waiting on land. Magellan waded ashore with his soldiers and attacked Lapulapu's forces, telling Datu Zula and his warriors to remain on the ships and watch. Magellan underestimated the army of Lapulapu, and, grossly outnumbered, Magellan and 14 of his soldiers were killed. The rest managed to reboard the ships.[citation needed]

The battle left the expedition with too few crewmen to man three ships, so they abandoned the "Concepción". The remaining ships – "Trinidad" and "Victoria" – sailed to the Spice Islands in present-day Indonesia. From there, the expedition split into two groups. The Trinidad, commanded by Gonzalo Gómez de Espinoza tried to sail eastward across the Pacific Ocean to the Isthmus of Panama. Disease and shipwreck disrupted Espinoza's voyage and most of the crew died. Survivors of the Trinidad returned to the Spice Islands, where the Portuguese imprisoned them. The Victoria continued sailing westward, commanded by Juan Sebastián Elcano, and managed to return to Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Spain in 1522.

Subsequent expeditions

[edit]After Magellan's expedition, four more expeditions were made to the islands, led by García Jofre de Loaísa in 1525, Sebastian Cabot in 1526, Álvaro de Saavedra Cerón in 1527, and Ruy López de Villalobos in 1542.[40]

In 1543, Villalobos named the islands of Leyte and Samar Las Islas Filipinas in honor of Philip II of Spain, at the time Prince of Asturias.[41]

Conquest of the islands

[edit]Philip II became King of Spain on January 16, 1556, when his father, Charles V, abdicated both the Spanish and HRE thrones, the latter went to his uncle, Ferdinand I. On his return to Spain in 1559, the king ordered an expedition to the Spice Islands, stating that its purpose was "to discover the islands of the west".[42] In reality its task was to conquer the Philippine islands.[43]

On November 19 or 20, 1564, a Spanish expedition of a mere 500 men led by Miguel López de Legazpi departed Barra de Navidad, New Spain, arriving at Cebu on February 13, 1565.[44] It was this expedition that established the first Spanish settlements. It also resulted in the discovery of the tornaviaje return route to Mexico across the Pacific by Andrés de Urdaneta,[45] heralding the Manila galleon trade, which lasted for two and a half centuries.

See also

[edit]- Anito

- Antonio de Morga

- Antonio Pigafetta

- Barangay (pre-colonial)

- Baybayin

- Boxer Codex

- Butuan (historical polity)

- Cainta (historical polity)

- Pangasinan (historical polity)

- Caboloan

- Dambana

- Datu

- Enrique of Malacca

- Ferdinand Magellan

- First Mass in the Philippines

- Tondo (historical polity)

- Lacandola Documents

- Lakan

- Lapulapu

- List of sovereign state leaders in the Philippines

- Luzones

- Ma-i

- Madja-as

- Maginoo

- Maharlika

- Maynila (historical polity)

- Kumintang (historical polity)

- Philippine shamans

- Pintados

- Pulilu

- Rajah

- Rajah Humabon

- Rajahnate of Butuan

- Rajahnate of Cebu

- Sandao

- Sanmalan

- Sultanate of Maguindanao

- Sultanate of Sulu

- Sultanate of Buayan

- Confederate States of Lanao

- Suyat

- Thimuay

- Timawa

- Warfare in pre-colonial Philippines

- Tawalisi

- Use of gold in early Philippine history

- History of the Philippines

- Prehistory of the Philippines

- History of the Philippines (Spanish Era 1521–1898)

- History of the Philippines (American Era 1898–1946)

- History of the Philippines (Third Republic 1946–65)

- History of the Philippines (Marcos Era 1965–86)

- History of the Philippines (Contemporary Era 1986–present)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Junker, Laura Lee (1999). Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8248-2035-0. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1992), Looking for the Prehispanic Filipino. New Day Publishers, Quezon City. 172 pp. ISBN 9711005247

- ^ Patricia Herbert; Anthony Crothers Milner (1989). South-East Asia: Languages and Literatures : a Select Guide. University of Hawaii Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8248-1267-6.

- ^ "Philippines | The Ancient Web". theancientweb.com. Archived from the original on October 3, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ Scott, William Henry. (1984). Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History (Revised Edition). New Day Publishers, Quezon City. ISBN 9711002264.

- ^ a b c Scott, William Henry (1979). "Class Structure in the Unhispanized Philippines". Philippine Studies. 27 (2). Ateneo de Manila University: 137–159. JSTOR 42632474.

- ^ a b c d e f Jocano, F. Landa (2001). Filipino Prehistory: Rediscovering Precolonial Heritage. Quezon City: Punlad Research House, Inc. ISBN 978-971-622-006-3.[page needed]

- ^ Scott, William Henry (1992). Looking for the Prehispanic Filipino.. p. 2.

- ^ Woods, Damon L. (1992). "Tomas Pinpin and the Literate Indio: Tagalog Writing in the Early Spanish Philippines" (PDF). UCLA Historical Journal. 12.

- ^ Postma, Antoon (1992). "The Laguna Copper-Plate Inscription: Text and Commentary". Philippine Studies. 40 (2): 182–203.

- ^ Newson, Linda A. (2009). Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. University of Hawaii Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8248-6197-1.

- ^ Miksic, John N. (2009). Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery. Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 978-981-4260-13-8.[page needed]

- ^ Sals, Florent Joseph (2005). The history of Agoo : 1578–2005. La Union: Limbagan Printhouse. p. 80.

- ^ a b Jocano, Felipe Jr. (2012). Wiley, Mark (ed.). A Question of Origins. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0742-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)[page needed] - ^ "Timeline of history". Archived from the original on November 23, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ Ring, Trudy; Robert M. Salkin & Sharon La Boda (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. pp. 565–569. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ Historical Atlas of the Republic. The Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. 2016. p. 64. ISBN 978-971-95551-6-2.

- ^ Legarda, Benito Jr. (2001). "Cultural Landmarks and their Interactions with Economic Factors in the Second Millennium in the Philippines". Kinaadman (Wisdom) A Journal of the Southern Philippines. 23: 40.

- ^ Carley, Michael (November 4, 2013) [2001]. "7". Urban Development and Civil Society: The Role of Communities in Sustainable Cities. Routledge. p. 108. ISBN 9781134200504. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

Each boat carried a large family group, and the master of the boat retained power as leader, or datu, of the village established by his family. This form of village social organization can be found as early as the 13th century in Panay, Bohol, Cebu, Samar and Leyte in the Visayas, and in Batangas, Pampanga and Tondo in Luzon. Evidence suggests a considerable degree of independence as small city-states with their heads known as datu, rajah or sultan.

- ^ Tan, Samuel K. (2008). A History of the Philippines. UP Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-971-542-568-1. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ Mallari, Perry Gil S. (April 5, 2014). "War and peace in precolonial Philippines". Manila Times. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Newson, Linda (2009) [2009]. "2". Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. University of Hawaii Press. p. 18. doi:10.21313/hawaii/9780824832728.001.0001. ISBN 9780824832728. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

Given the significance of the size and distribution of the population to the spread of diseases and their ability to become endemic, it is worth commenting briefly on the physical and human geography of the Philippines. The hot and humid tropical climate would have generally favored the propagation of many diseases, especially water-borne infections, though there might be regional or seasonal variations in climate that might affect the incidence of some diseases. In general, however, the fact that the Philippines comprise some seven thousand islands, some of which are uninhabited even today, would have discouraged the spread of infections, as would the low population density.

- ^ "The Islands of Leyte and Samar – National Commission for Culture and the Arts". Archived from the original on July 12, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ^ "ILONGOT – National Commission for Culture and the Arts". Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ^ "GLIMPSES: Peoples of the Philippines". Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ^ Glover, Ian; Bellwood, Peter; Bellwood, Peter S.; Glover, Dr (2004). Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to History. Psychology Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-415-29777-6. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

- ^ Scott 1994.

- ^ Osborne, Milton (2004). Southeast Asia: An Introductory History (Ninth ed.). Australia: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74114-448-2.[page needed]

- ^ Baybayin, the Ancient Philippine script Archived August 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed September 4, 2008.

- ^ Morrow, Paul. "Baybayin Styles & Their Sources". Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ de San Agustin, Caspar (1646). Conquista de las Islas Filipinas 1565–1615.

'Tienen sus letras y caracteres como los malayos, de quien los aprendieron; con ellos escriben con unos punzones en cortezas de caña y hojas de palmas, pero nunca se les halló escritura antinua alguna ni luz de su orgen y venida a estas islas, conservando sus costumbres y ritos por tradición de padres a hijos din otra noticia alguna.'

- ^ Go, Bon Juan (2005). "Ma'l in Chinese Records – Mindoro or Bai? An Examination of a Historical Puzzle". Philippine Studies. 53 (1). Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University: 119–138. Retrieved October 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Patanne, E. P. (1996). The Philippines in the 6th to 16th Centuries. San Juan: LSA Press. ISBN 971-91666-0-6.

- ^ Scott, William Henry. (1984). "Societies in Prehispanic Philippines". Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. p. 70. ISBN 971-10-0226-4.

- ^ McAmis, Robert Day. (2002). Malay Muslims: The History and Challenge of Resurgent Islam in Southeast Asia. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 18–24, 53–61. ISBN 0-8028-4945-8. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ Zaide, Gregorio F.; Sonia M. Zaide (2004). Philippine History and Government (6th ed.). All-Nations Publishing Company. pp. 52–55. ISBN 971-642-222-9.

- ^ Zaide 2006, p. 78

- ^ Zaide 2006, pp. 80–81

- ^ Zaide 2006, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Scott 1985, p. 51.

- ^ Williams 2008, p. 14

- ^ Williams, Patrick (2008). "Philip II, the Philippines and the Hispanic World". In Ramírez, Dámaso de Lario (ed.). Re-shaping the World: Philip II of Spain and His Time. Ateneo University Press. pp. 13–33. ISBN 978-971-550-556-7.

- ^ M.c. Halili (2004). Philippine History' 2004 Ed.-halili. Rex Bookstore, Inc. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.

- ^ Zaide 1939, p. 113

Further reading

[edit]- Scott, William Henry (1985), Cracks in the parchment curtain and other essays in Philippine history, New Day Publishers, ISBN 978-971-10-0074-5.

- Zaide, Gregorio F. (1939), Philippine History and Civilization, Philippine Education Co..

- Zaide, Sonia M (2006), The Philippines: A Unique Nation, All-Nations Publishing Co Inc, Quezon City, ISBN 971-642-071-4.

External links

[edit] Media related to History of the Philippines (900–1565) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of the Philippines (900–1565) at Wikimedia Commons- Pre-colonial Manila Archived December 22, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

History of the Philippines (900–1565)

View on GrokipediaPrimary Evidence and Sources

Documentary Artifacts like the Laguna Copperplate Inscription

The Laguna Copperplate Inscription (LCI), discovered in 1989 near the Lumbang River in Barangay Wawa, Lumban, Laguna province, represents the earliest surviving written record from the Philippines, dated to the Saka era year 822, equivalent to 10 May 900 CE in the Gregorian calendar.[12] This thin, blackened copper plate, measuring approximately 20 by 17.5 centimeters and weighing 925 grams, was dredged from a riverbed and subsequently acquired by the National Museum of the Philippines in 1990 for study.[13] Its inscription, executed in a form of Old Malay using the Kawi script derived from Pallava Grantha, incorporates Sanskrit loanwords and indigenous toponyms, evidencing literacy and administrative sophistication in 10th-century Luzon.[12] [14] The document functions as a royal decree of manumission, absolving a certain Namwaran, along with his relatives Jayadewa and Dapunta Hyu Bajah Param, from a debt obligation of one-sixth of a kati—approximately 333 grams—of gold, payable to the "Lord Minister of Dewata."[14] It references polities such as Tondo, Pailah, and Puliran, and invokes higher authorities including the "Supreme Lord" (likely a sovereign in the Srivijayan mandala) and the "Lord in charge of Tagalog," indicating interconnected chiefdoms with hierarchical titles like parammahesvara and hayam wuruk, reflective of Indianized cultural influences via maritime trade networks with Java and Sumatra.[12] The text employs a Hindu-Buddhist lunisolar calendar for dating, underscoring religious and calendrical adoption from Southeast Asian intermediaries rather than direct Indian contact.[14] This artifact's significance lies in its demonstration of pre-colonial Philippine societies' engagement in written legal transactions, debt systems, and supra-local diplomacy centuries before European arrival, countering narratives of isolated, non-literate barangays.[13] It implies economic complexity, with gold as a standardized medium, and cultural ties to the Srivijaya Empire, facilitating the flow of Indic scripts and concepts into the archipelago.[12] No comparable indigenous documentary inscriptions from the 900–1565 period have been identified, rendering the LCI uniquely pivotal for reconstructing early political and social structures through direct epigraphic evidence rather than solely foreign chronicles.[12]Archaeological Discoveries and Sites

Archaeological evidence from the Philippines during 900–1565 supplements sparse documentary records, revealing complex societies with maritime prowess, international trade, and metallurgical expertise. Excavations at key sites like Butuan in Mindanao and Calatagan in Luzon have uncovered boats, burials, ceramics, and gold artifacts indicative of interconnected polities engaging in regional commerce with China, Southeast Asia, and beyond. These findings demonstrate indigenous technological continuity, such as plank-built vessels, and economic specialization in goldworking, often tied to elite hierarchies.[15][16][17] The Butuan archaeological complex in Agusan del Norte, excavated primarily in the 1970s, centers on riverine sites like Ambangan and Libertad, yielding evidence of a thriving port from the 10th to 15th centuries. At least 11 balangay boats, large sewn-plank vessels up to 15 meters long using edge-peg construction, date to the 10th–13th centuries, representing the highest concentration of such prehistoric watercraft in Southeast Asia and affirming advanced indigenous shipbuilding for open-sea voyages. Wooden coffin burials from the 14th–15th centuries feature intentionally deformed frontal skulls, accompanied by trade goods including Chinese ceramics (10th–15th centuries), Thai wares (14th–15th), Persian items, and over 100 clay crucibles for gold smelting, alongside ornaments like earrings and lingling-o pendants. An ivory seal inscribed with Indian script and a silver paleograph further indicate administrative and mercantile activities, positioning Butuan as a hub for gold export and exotic imports.[15][18][17] In Calatagan Peninsula, Batangas, systematic digs from the 1940s–1960s, including over 1,000 burials at sites like Pulong Bacao and Kay Tomas, date to the 15th century based on imported ceramics. Grave goods encompass local undecorated and stamped earthenware pots, Chinese Yuan–Ming porcelains (bowls, jarlets), Vietnamese and Thai stonewares, glass beads, shells for currency, Chinese coins, and gold fragments, evidencing stratified burial practices with elites receiving foreign prestige items. The Calatagan Pot, a ritual vessel with undeciphered script possibly ancestral to Baybayin, was recovered here, alongside signs of interpersonal violence like cranial fractures in skeletons. These assemblages highlight Luzon's integration into East Asian trade circuits and ritual economies.[16] Gold artifacts from these and related sites, such as Surigao hoards, include intricate jewelry like forearm bands, barter rings, and funerary masks from the 10th–13th centuries, sourced from abundant local deposits and processed via lost-wax casting. Such regalia, often found in elite contexts, underscore gold's role in status display and exchange, with Butuan's crucibles confirming on-site fabrication for export.[17][19]Social Organization

Hierarchical Classes and Slavery

Pre-colonial Philippine society from the 10th to 16th centuries featured a hierarchical structure divided into three primary estates: the nobility (maginoo), freemen (timawa or maharlika), and dependents (alipin).[20] This organization was evident in barangay communities of 30 to 100 households, where authority derived from birthright, martial prowess, and economic control rather than rigid caste inheritance.[20] Nobles held political and military leadership, freemen provided service in exchange for protection, and dependents rendered tribute or labor, reflecting a system sustained by kinship, warfare, and debt relations rather than centralized state enforcement.[20] The ruling class consisted of datus or maginoo, birthright aristocrats who governed barangays and led raids for captives and resources.[20] A datu typically inherited status through lineage but could ascend via demonstrated valor in combat, commanding vassal loyalty through redistribution of spoils.[20] In Luzon, maharlikas formed a warrior subclass within this nobility, serving datus in battle while retaining personal land and arms, though their autonomy diminished over time due to economic pressures.[20] Timawas, comprising the freemen estate, were non-aristocratic vassals who owed military or agricultural service to datus but enjoyed personal freedom, land usufruct, and the ability to shift allegiances between leaders.[20] This class formed the bulk of the population, including farmers, artisans, and fighters, with origins often tracing to freed alipin or lesser maginoo descendants.[20] Alipin represented the dependent estate, bound by obligation rather than absolute ownership by masters, with status acquired through debt, wartime capture, purchase, or inheritance.[20] Two main types existed: alipin namamahay, householders who retained family units, personal property, and land rights (paying tribute such as half their crops or four cavans of rice annually), functioning more as serfs than chattel; and alipin sa gigilid, or "hearth slaves," fully attached to a master's household without independent property, liable to sale, transfer, or even ritual sacrifice.[20] Gintubo denoted inherited alipin status, passed down maternally or through parental bondage.[20] Unlike transatlantic chattel slavery, alipin could own movables, marry freely (with offspring inheriting partial status based on parental mix, e.g., half-alipin from alipin-timawa unions), and achieve manumission by repaying debts in gold (typically 10 taels for namamahay or 30 pesos for sa gigilid).[20] Social mobility existed, as accumulated debt could demote timawas to alipin, while prosperous alipin might buy freedom and rise, though creditors sometimes exploited distinctions to enforce harsher terms.[20] Evidence for this structure derives primarily from 16th-century Spanish chroniclers like Miguel de Loarca (1582) and Fray Martín de Rada (1577), who documented Visayan and Tagalog practices, corroborated by artifacts such as the 900 AD Laguna Copperplate Inscription implying early debt-based bondage.[20] Regional variations occurred, with Visayans emphasizing tumao nobles and similar alipin divisions, while northern groups like the Tagalogs highlighted maharlika autonomy, but the core hierarchy persisted across islands due to shared maritime and kinship economies.[20] Slavery's scale reflected chronic population shortages from warfare and disease, incentivizing manumission to bolster labor pools rather than perpetual bondage.[20]Family Structures, Gender Roles, and Daily Life

Pre-colonial Philippine societies from 900 to 1565 were organized around kinship-based barangays, where the basic family unit consisted of parents, children, slaves, and relatives, forming the core of social and economic life.[21] Kinship was traced bilaterally through both maternal and paternal lines, emphasizing equal inheritance rights for sons and daughters unless otherwise specified, with children from outside wedlock receiving a lesser share.[22] Extended families lived in stilt houses accommodating multiple households, fostering communal support and allegiance to the datu leader.[21] Marriage was consensual and often arranged through negotiations involving bride-prices such as gold, slaves, or gongs paid by the groom to the bride's family, with grooms sometimes providing labor service for a year.[21][22] Divorce was readily available for reasons like incompatibility, with dowries redistributed—typically forfeited by the initiating party—and remarriage common, reflecting serial monogamy more than strict polygyny, though elite datus practiced the latter with secondary wives or concubines.[21][22] Adoption integrated children into families, as seen in cases like Rajah Soliman's adoption of his deceased brother's offspring, ensuring continuity of lineage and property.[21] Gender roles exhibited a clear division of labor, with men responsible for heavy fieldwork like clearing swidden plots, boat-building, blacksmithing, hunting, fishing, and warfare, often marked by tattoos signifying valor.[21] Women handled household management, rice harvesting, weaving abaca or cotton cloth, pottery-making, and cooking, while also serving as shamans (babaylan) who led rituals and held spiritual authority, sometimes amassing wealth equivalent to 350 pesos over two years.[21] High-status women, such as binokot daughters of datus, were secluded to preserve virginity and light skin, enhancing marriage value, yet women generally retained property ownership, equal legal standing in disputes, and the ability to initiate divorce.[21][22] Daily life centered on subsistence activities in barangays of 30 to 100 families, with agriculture dominated by rice cultivation via swidden methods, supplemented by root crops, fishing from outrigger boats, and raising domestic animals like pigs and chickens.[21] Communities emphasized hygiene through frequent bathing, communal labor for fields and feasts, and social rituals involving betel nut chewing, tuba distillation for drinkfests, and oral epics recited during gatherings.[21] Household routines included gendered tasks supported by slaves, with diets of rice, fish, and vegetables, and cultural practices like ancestor veneration tying daily existence to spiritual kinship networks.[21] Regional variations existed, such as Igorot gold mining or Cagayan rice farming, but maritime trade and seasonal cycles unified island-wide patterns.[21]Political Systems

Barangay Chiefdoms and Leadership

The barangay constituted the basic unit of socio-political organization in pre-colonial Philippine societies from at least the 10th century, functioning as a kinship-based chiefdom led by a datu who commanded the allegiance of 30 to 100 households, typically encompassing a few hundred individuals. This structure emphasized personal loyalty to the datu rather than territorial sovereignty, with communities often relocating based on resource availability or conflict.[20][23] The datu held multifaceted authority, serving as governor, judge, military commander, and spiritual intermediary in many polities. Responsibilities included settling disputes through customary law, leading raids or defenses (known as mangayaw or magahat), apportioning communal lands and harvests, and mediating alliances with neighboring barangays. Judicial powers allowed the datu to impose fines, enslavement, or execution for offenses like murder or theft, often executing sentences personally when personal honor was at stake; communal consensus via elders influenced broader decisions.[23][20] Leadership succession was primarily hereditary within the noble maginoo class, transmitted through male lines via endogamous marriages to preserve pedigree, though competitive merit—demonstrated by prowess in battle, wealth from trade or raids, or sagacity—enabled selection among eligible kin by a council of elders or fellow nobles. Female datus existed in some instances, particularly where capable women assumed roles absent male heirs. This system balanced aristocratic continuity with pragmatic evaluation, preventing stagnation through proven competence.[23] Archaeological and documentary evidence, such as the Laguna Copperplate Inscription dated to 900 CE, reveals early precedents for this hierarchy, documenting titled officials including "tuhan" (regional leaders of locales like Puliran and Pailah) and "pamgat" (chiefs), alongside a "senapati" (commander), who witnessed a debt remission under a structured authority in the Laguna region, implying decentralized yet interconnected chiefdoms with legal and economic oversight. Spanish chroniclers from the 1580s, drawing on observations of extant systems, corroborate the datu's role, attributing it to indigenous traditions predating contact, though filtered through colonial lenses.[3][23]Regional Variations Across Islands

In Luzon, particularly the Tagalog polities around Manila Bay such as Tondo and Maynila, political structures showed higher degrees of centralization compared to other regions, with paramount leaders like the lakan or rajah overseeing networks of subordinate datus through tribute, alliances, and control of trade routes. The Laguna Copperplate Inscription from 900 CE documents a debt remission involving a rajah of Tondo and officials bearing Indianized titles such as maharajah and guapunan, suggesting a hierarchical system integrated with regional commerce and possibly Srivijayan influences.[24] By the 16th century, Tondo's leadership maintained influence over approximately 20-30 barangays via kinship ties and economic leverage from exporting beeswax, deerskins, and gold to China, though authority remained personalistic rather than bureaucratic.[24] Visayan islands featured more decentralized confederations of barangays, often led by datus selected through consensus among freemen (timawa) and emphasizing martial prowess over hereditary prestige, as observed in Panay and Cebu chiefdoms. In Cebu, Rajah Humabon's polity in the early 16th century comprised around 12-15 allied barangays with fleets for raiding and defense, but internal autonomy persisted, with subordinate leaders retaining control over local resources like rice fields and boat-building.[24] Panay's settlements, while lacking the legendary centralized "Madja-as" of later folklore—which historical analysis attributes to 19th-20th century fabrication rather than primary evidence—operated as loose alliances vulnerable to external threats, prompting migrations and pacts as recorded in Spanish contacts around 1569.[25] This structure fostered frequent inter-barangay warfare but enabled flexible responses to trade opportunities with Borneo and the Moluccas.[24] In Mindanao, polities like the Rajahnate of Butuan exhibited kingdom-scale organization from the 10th to 13th centuries, with rajahs directing tributary missions to China's Song dynasty—evidenced by 11th-century records of 200+ tribute items including gold and beeswax—and commanding large balangay fleets for riverine and maritime control.[24] Butuan's structure integrated multiple barangays under a central authority supported by metallurgy and shipbuilding expertise, contrasting with smaller northern units. Southern Mindanao diverged further with Islam's arrival via Sulu around 1250-1300 CE, forming sultanates like Sulu and Maguindanao by the 15th century, where sultans and datus adopted Sharia-influenced hierarchies, expanded territories through jihad and slave-raiding, and formalized alliances with Brunei, leading to more stratified classes and enduring resistance to external domination.[24][25] These variations stemmed causally from geographic factors—island fragmentation limiting unification, coastal access enabling trade hierarchies—and external contacts, with Indianized elements stronger in trade hubs like Tondo and Butuan, while interior and central islands retained simpler kinship-based systems.[24] Archaeological evidence, including Butuan's 9th-10th century boat burials and Luzon's gold artifacts, corroborates textual accounts of differential complexity without implying uniform "state" formation across the archipelago.[26]Inter-Polity Warfare and Alliances

Inter-polity warfare in the precolonial Philippines was characterized by frequent small-scale raids and occasional pitched battles among barangay chiefdoms, driven primarily by the capture of slaves for labor and trade, as well as disputes over resources, territory, and prestige.[24] Slaves, known as alipin, formed a significant portion of the population—up to 80% in some accounts—and were acquired through warfare, debt, or birth, with raids targeting neighboring settlements to replenish this economic base.[24] Warfare tactics emphasized mobility, utilizing swift balangay outrigger boats for coastal and riverine assaults, ambushes in forested terrain, and close-quarters combat with weapons such as wooden shields (kalasag), spears (sibat), bows (pana), and edged blades like the kampilan sword in later periods.[24] Archaeological evidence, including hilltop fortifications (idjang) in Batanes dated to circa 1200–1500 CE, indicates defensive responses to such raids, likely from internal rivals or external maritime threats, with stone walls up to 10 meters high protecting communities of several hundred inhabitants.[27] Larger conflicts arose between regional polities, often escalating from raids into organized campaigns. In the Visayas, the Kedatuan of Madja-as, a loose confederation of barangays on Panay Island established around the 13th century, engaged in defensive wars against incursions from neighboring groups and external powers, including reported resistance to Srivijayan influences and later Chola expansions from India via Southeast Asian networks.[28] Ethnohistoric accounts preserved in 16th-century records suggest inter-island rivalries, such as Visayan raids on Luzon coastal settlements for plunder, with polities like Cebu and Butuan competing for control of trade routes linking to Chinese and Borneo ports by the 14th–15th centuries.[24] In northern Luzon, chiefdoms around Tondo and Maynila maintained hegemony through martial prowess, with evidence of fortified river-mouth positions facilitating both offensive expeditions and defense against inland rivals like Namayan, though specific battle dates remain elusive due to reliance on oral traditions recorded post-contact.[29] Alliances among polities were fluid and kinship-based, often forged through inter-datu marriages to secure mutual defense or trade access, rather than formal treaties.[24] Barangays could coalesce into temporary confederacies under a paramount datu for joint raids or against common foes, as seen in the Madja-as structure, where allied chiefdoms spanned multiple islands and coordinated via maritime networks.[28] Such pacts were pragmatic, dissolving over leadership disputes or resource gains; for instance, Luzon polities like Tondo formed loose networks with subordinate barangays for riverine dominance, while Visayan groups allied sporadically against Moro slavers from Mindanao in the 15th century.[24] These arrangements facilitated the spread of technologies like ironworking via allied trade but were undermined by betrayal, as chronicled in post-arrival accounts reflecting pre-1565 dynamics.[29] Overall, warfare and alliances reinforced hierarchical structures, with victorious datus gaining followers and status, perpetuating a cycle of expansion and rivalry amid growing external commerce.[24]Economy and Trade

Agricultural and Local Production

Pre-colonial Philippine societies from 900 to 1565 primarily relied on swidden (slash-and-burn or kaingin) agriculture for upland rice cultivation, involving the clearing of forested hillsides by felling trees and burning slash to enrich soil with ash, followed by planting using dibble sticks where men poked holes and women inserted seeds.[30] This method produced dry rice varieties suited to natural drainage on slopes, with fields rotated or abandoned after 2–3 years to allow soil regeneration, reflecting low-intensity subsistence adapted to tropical environments rather than permanent intensive farming.[30] In lowland riverine areas, particularly in parts of Luzon and possibly Visayas, limited wet-rice cultivation occurred through transplanting seedlings into flooded paddies, supporting up to 41 documented varieties by the 16th century, though yields remained insufficient for daily consumption across most communities.[30] Root crops served as dietary staples alongside rice, including taro (Colocasia esculenta, known as gabi or bungangon), yams (ubi), and millet, which were planted in swidden plots or home gardens for reliable harvests less vulnerable to dry spells or pests affecting rice.[30] Supplementary crops and gathered foods included bananas, sago starch extracted from palm trunks via grating and washing, and wild edibles from forests, providing carbohydrates when rice fields lay fallow.[30] Protein sources complemented agriculture through communal fishing using weirs, nets, traps, and hooks in rivers, lakes, and coasts, as well as hunting with blowpipes, bows, and snares targeting deer, wild pigs, and birds, with practices varying by island ecology—coastal barangays emphasizing marine resources while interior groups focused on terrestrial game.[30] Harvesting was labor-intensive and gendered: women cut rice panicles individually with small knives (yabi or gunit), threshing by beating against logs and winnowing with baskets, then storing in elevated field granaries (pilon) or under house floors to deter rodents and pests.[30] Rice preparation involved boiling unhusked grains in water without seasoning, pounded into cakes or porridge for meals, while root crops were similarly boiled; surpluses formed tribute (buwis) to datus, underscoring agriculture's role in social hierarchies rather than surplus economies.[30] Archaeological continuity from Neolithic sites suggests these practices persisted from earlier Austronesian introductions of rice around 2000 BCE, with no evidence of large-scale irrigation systems like terraces before Spanish contact, though localized bunding occurred in fertile valleys.[31] Local non-agricultural production supported subsistence through household crafts, including pottery fired in open pits for storage jars (burnay) and cooking vessels, weaving of abaca fiber into mats, clothing, and sails using backstrap looms, and blacksmithing of iron tools like bolos and dibble points from imported ores smelted in clay furnaces.[32] These activities, often kin-based, produced goods for barter within barangays, with goldworking for ornaments emerging in polities like Tondo by the 10th century, as evidenced by artifacts, but remained small-scale without mechanized industry.Maritime Trade Routes and Goods

Philippine polities maintained maritime trade routes primarily through the South China Sea and Sulu Sea, connecting ports in Luzon, Mindoro, the Visayas, and Mindanao to Chinese coastal cities like Guangzhou and Quanzhou, as well as Southeast Asian hubs in Vietnam, Borneo, and the Malay Peninsula, from the 10th century onward.[33] These routes formed part of the broader Nanhai (South Sea) trade network, with Filipino traders navigating monsoon winds to reach Fujian and Guangdong provinces by at least 982 AD, as evidenced by Song dynasty records of Ma-i envoys and merchants arriving in Canton.[34] Archaeological evidence from sites like Butuan confirms active participation in regional circuits, with imported ceramics from China, Thailand, and Vietnam appearing in 10th–13th century layers, indicating voyages eastward to the Lingayen Gulf and southward via the Sulu Archipelago.[35] Key trading polities included Ma-i (likely centered on Mindoro or southern Luzon), which dispatched annual tribute-trade missions to China during the Song (960–1279) and Yuan (1271–1368) dynasties, and Tondo in Manila Bay, which served as a redistribution center for goods funneled to Java and the Srivijaya Empire.[36] By the 15th century, eastern routes gained prominence, as demonstrated by shipwrecks such as Pandanan (off Palawan) and Lena Shoal (South China Sea), which carried Vietnamese Dong Son drums, Thai sawankhalok wares, and Chinese celadon porcelain, suggesting circuits linking the Visayas to Annam and Champa.[7] These pathways relied on outrigger vessels capable of long-haul voyages, with polities like Butuan facilitating transshipment of goods from interior riverine networks to coastal entrepôts.[37] Exported commodities from Philippine ports emphasized forest and marine products, including beeswax, cotton textiles, tortoise shells, true pearls, medicinal betel nuts, and yuta cloth, as detailed in the 1225 Song text Zhu Fan Zhi for Ma-i traders bartering in Quanzhou markets.[36] Gold ornaments and abaca fiber also featured in exchanges, with Butuan excavations yielding evidence of local metallurgy integrated into export streams.[35] Imports comprised prestige goods like porcelain vessels, silk fabrics, iron implements, and glass beads, which archaeological assemblages from 10th–16th century sites attribute to Chinese, Vietnamese, and Thai origins, often arriving in bulk cargoes that bolstered chiefly prestige economies.[38]| Category | Exported Goods | Imported Goods |

|---|---|---|

| Organic | Beeswax, betel nuts, cotton/yuta cloth | Silk fabrics |

| Marine/Forest | Tortoise shells, pearls, abaca | - |

| Mineral | Gold | Iron caldrons, glass beads |

| Ceramics/Metal | - | Porcelain (Chinese celadon), Thai wares, Vietnamese drums[36][35][7] |