Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Myelodysplastic syndrome

View on Wikipedia

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Preleukemia, myelodysplasia[1][2] |

| |

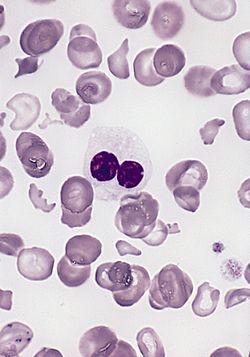

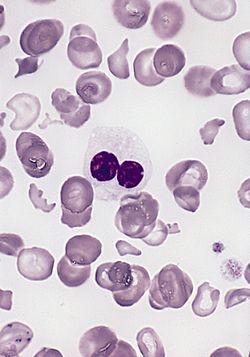

| Blood smear from a person with myelodysplastic syndrome. A hypogranular neutrophil with a pseudo-Pelger-Huet nucleus is shown. There are also abnormally shaped red blood cells, in part related to removal of the spleen. | |

| Specialty | Hematology, oncology |

| Symptoms | None, feeling tired, shortness of breath, easy bleeding, frequent infections[3] |

| Risk factors | Previous chemotherapy, radiation therapy, certain chemicals such as tobacco smoke, pesticides, and benzene, exposure to mercury or lead[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood test, bone marrow biopsy[3] |

| Treatment | Supportive care, medications, stem cell transplantation[3] |

| Medication | Lenalidomide, antithymocyte globulin, azacitidine[3] |

| Prognosis | Typical survival time 2.5 years[3] |

A myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is one of a group of cancers in which blood cells in the bone marrow do not mature, and as a result, do not develop into healthy blood cells.[3] Early on, no symptoms are typically seen.[3] Later, symptoms may include fatigue, shortness of breath, bleeding disorders, anemia, or frequent infections.[3] Some types may develop into acute myeloid leukemia.[3]

Risk factors include previous chemotherapy or radiation therapy, exposure to certain chemicals such as tobacco smoke, pesticides, and benzene, and exposure to heavy metals such as mercury or lead.[3] Problems with blood cell formation result in some combination of low red blood cell, platelet, and white blood cell counts.[3] Some types of MDS cause an increase in the production of immature blood cells (called blasts), in the bone marrow or blood.[3] The different types of MDS are identified based on the specific characteristics of the changes in the blood cells and bone marrow.[3]

Treatments may include supportive care, drug therapy, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.[3] Supportive care may include blood transfusions, medications to increase the making of red blood cells, and antibiotics.[3] Drug therapy may include the medications lenalidomide, antithymocyte globulin, and azacitidine.[3] Some people can be cured by chemotherapy followed by a stem-cell transplant from a donor.[3]

About seven per 100,000 people are affected by MDS; about four per 100,000 people newly acquire the condition each year.[4] The typical age of onset is 70 years.[4] The prognosis depends on the type of cells affected, the number of blasts in the bone marrow or blood, and the changes present in the chromosomes of the affected cells.[3] The average survival time following diagnosis is 2.5 years.[4] MDS was first recognized in the early 1900s;[5] it came to be called myelodysplastic syndrome in 1976.[5]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Signs and symptoms are nonspecific and generally related to the blood cytopenias:

- Anemia (low RBC count or reduced hemoglobin) – chronic tiredness, shortness of breath, chilled sensation, sometimes chest pain[6]

- Neutropenia (low neutrophil count) – increased susceptibility to infection[7]

- Thrombocytopenia (low platelet count) – increased susceptibility to bleeding and ecchymosis (bruising), as well as subcutaneous hemorrhaging resulting in purpura or petechiae[8][9]

Many individuals are asymptomatic, and blood cytopenia or other problems are identified as a part of a routine blood count:[10]

- Neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia

- Splenomegaly or rarely hepatomegaly

- Abnormal granules in cells, abnormal nuclear shape and size

- Chromosome abnormality, including chromosomal translocations and abnormal chromosome number

Patients with MDS have an overall risk of almost 30% for developing acute myelogenous leukemia.[11]

Anemia dominates the early course. Most symptomatic patients complain of the gradual onset of fatigue and weakness, dyspnea, and pallor, but at least half the patients are asymptomatic and their MDS is discovered only incidentally on routine blood counts. Fever, weight loss and splenomegaly should point to a myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm (MDS/MPN) rather than pure myelodysplastic process.[12]

Cause

[edit]Some people have a history of exposure to chemotherapy (especially alkylating agents such as melphalan, cyclophosphamide, busulfan, and chlorambucil) or radiation (therapeutic or accidental), or both (e.g., at the time of stem cell transplantation for another disease). Workers in some industries with heavy exposure to hydrocarbons, such as the petroleum industry, have a slightly higher risk of contracting the disease than the general population. Xylene and benzene exposures have been associated with myelodysplasia. Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange are at risk of developing MDS.[13] A link may exist between the development of MDS "in atomic-bomb survivors 40 to 60 years after radiation exposure" (in this case, referring to people who were in close proximity to the dropping of the atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II).[14] Children with Down syndrome are susceptible to MDS, and a family history may indicate a hereditary form of sideroblastic anemia or Fanconi anemia.[15] GATA2 deficiency and SAMD9/9L syndromes each account for about 15% of MDS cases in children.[16]

Pathophysiology

[edit]MDS most often develops without an identifiable cause. Risk factors include exposure to an agent known to cause DNA damage, such as radiation, benzene, and certain chemotherapies; other risk factors have been inconsistently reported. Proving a connection between a suspected exposure and the development of MDS can be difficult, but the presence of genetic abnormalities may provide some supportive information. Secondary MDS can occur as a late toxicity of cancer therapy (therapy-associated MDS, t-MDS). MDS after exposure to radiation or alkylating agents such as busulfan, nitrosourea, or procarbazine, typically occurs 3–7 years after exposure and frequently demonstrates loss of chromosome 5 or 7. MDS after exposure to DNA topoisomerase II inhibitors occurs after a shorter latency of only 1–3 years and can have an 11q23 translocation. Other pre-existing bone-marrow disorders, such as acquired aplastic anemia following immunosuppressive treatment and Fanconi anemia, can evolve into MDS.[15]

MDS is thought to arise from mutations in the multipotent bone-marrow stem cell, but the specific defects responsible for these diseases remain poorly understood. Differentiation of blood precursor cells is impaired, and a significant increase in levels of apoptotic cell death occurs in bone-marrow cells. Clonal expansion of the abnormal cells results in the production of cells that have lost the ability to differentiate. If the overall percentage of bone-marrow myeloblasts rises over a particular cutoff (20% for WHO and 30% for FAB), then transformation to acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is said to have occurred. The progression of MDS to AML is a good example of the multistep theory of carcinogenesis in which a series of mutations occurs in an initially normal cell and transforms it into a cancer cell.[17]

Although recognition of leukemic transformation was historically important (see History), a significant proportion of the morbidity and mortality attributable to MDS results not from transformation to AML, but rather from the cytopenias seen in all MDS patients. While anemia is the most common cytopenia in MDS patients, given the ready availability of blood transfusion, MDS patients rarely experience injury from severe anemia. The two most serious complications in MDS patients resulting from their cytopenias are bleeding (due to lack of platelets) or infection (due to lack of white blood cells). Long-term transfusion of packed red blood cells leads to iron overload.[18]

Genetics

[edit]The recognition of epigenetic changes in DNA structure in MDS has explained the success of two (namely the hypomethylating agents 5-azacytidine and decitabine) of three (the third is lenalidomide) commercially available medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat MDS. Proper DNA methylation is critical in the regulation of proliferation genes, and the loss of DNA methylation control can lead to uncontrolled cell growth and cytopenias. The recently approved DNA methyltransferase inhibitors take advantage of this mechanism by creating a more orderly DNA methylation profile in the hematopoietic stem cell nucleus, thereby restoring normal blood counts and retarding the progression of MDS to acute leukemia.[19]

Some authors have proposed that the loss of mitochondrial function over time leads to the accumulation of DNA mutations in hematopoietic stem cells, and this accounts for the increased incidence of MDS in older patients. Researchers point to the accumulation of mitochondrial iron deposits in the ringed sideroblast as evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction in MDS.[20]

DNA damage

[edit]Hematopoietic stem cell aging is thought to be associated with the accrual of multiple genetic and epigenetic aberrations leading to the suggestion that MDS is, in part, related to an inability to adequately cope with DNA damage.[21] An emerging perspective is that the underlying mechanism of MDS could be a defect in one or more pathways that are involved in repairing damaged DNA.[22] In MDS an increased frequency of chromosomal breaks indicates defects in DNA repair processes.[23] Also, elevated levels of 8-oxoguanine were found in the DNA of a significant proportion of MDS patients, indicating that the base excision repair pathway that is involved in handling oxidative DNA damages may be defective in these cases.[23]

5q- syndrome

[edit]Since at least 1974, the deletion in the long arm of chromosome 5 has been known to be associated with dysplastic abnormalities of hematopoietic stem cells.[24][25] By 2005, lenalidomide, a chemotherapy drug, was recognized to be effective in MDS patients with the 5q- syndrome,[26] and in December 2005, the US FDA approved the drug for this indication. Patients with isolated 5q-, low IPSS risk, and transfusion dependence respond best to lenalidomide. Typically, the prognosis for these patients is favorable, with a 63-month median survival. Lenalidomide has dual action, by lowering the malignant clone number in patients with 5q-, and by inducing better differentiation of healthy erythroid cells, as seen in patients without 5q deletion.[citation needed]

Splicing factor mutations

[edit]Mutations in splicing factors have been found in 40–80% of people with MDS, with a higher incidence of mutations detected in people who have more ring sideroblasts.[27]

IDH1 and IDH2 mutations

[edit]Mutations in the genes encoding for isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 (IDH1 and IDH2) occur in 10–20% of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome,[28] and confer a worsened prognosis in low-risk MDS.[29] Because the incidence of IDH1/2 mutations increases as the disease malignancy increases, these findings together suggest that IDH1/2 mutations are important drivers of progression of MDS to a more malignant disease state.[29]

GATA2 deficiency

[edit]GATA2 deficiency is a group of disorders caused by a defect, familial, or sporadic inactivating mutations, in one of the two GATA2 genes. These autosomal dominant mutations cause a reduction in the cellular levels of the gene's product, GATA2. The GATA2 protein is a transcription factor critical for the embryonic development, maintenance, and functionality of blood-forming, lymph-forming, and other tissue-forming stem cells. In consequence of these mutations, cellular levels of GATA2 are low, and individuals develop over time hematological, immunological, lymphatic, or other presentations. Prominent among these presentations is MDS that often progresses to acute myelocytic leukemia, or less commonly, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.[30][31]

Transient myeloproliferative disease

[edit]Transient myeloproliferative disease, renamed Transient Abnormal Myelopoiesis (TAM),[32] is the abnormal proliferation of a clone of noncancerous megakaryoblasts in the liver and bone marrow. The disease is restricted to individuals with Down syndrome or genetic changes similar to those in Down syndrome, develops during pregnancy or shortly after birth, and resolves within 3 months, or in about 10% of cases, progresses to acute megakaryoblastic leukemia.[33][30][34]

Diagnosis

[edit]The elimination of other causes of cytopenias, along with a dysplastic bone marrow, is required to diagnose a myelodysplastic syndrome, so differentiating MDS from other causes of anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia is important.[35] MDS is diagnosed with any type of cytopenia (anemia, thrombocytopenia, or neutropenia) being present for at least 6 months, the presence of at least 10% dysplasia or blasts (immature cells) in 1 cell lineage, and MDS associated genetic changes, molecular markers or chromosomal abnormalities.[36]

A typical diagnostic investigation includes:

- Full blood count and examination of blood film: The blood film morphology can provide clues about hemolytic anemia, clumping of the platelets leading to spurious thrombocytopenia, or leukemia.

- Blood tests to eliminate other common causes of cytopenias such as lupus, hepatitis, B12, folate, or other vitamin deficiencies, kidney failure or heart failure, HIV, hemolytic anemia, monoclonal gammopathy: Age-appropriate cancer screening should be considered for all anemic patients.

- Bone marrow examination by a hematopathologist: This is required to establish the diagnosis since all hematopathologists consider dysplastic marrow the key feature of myelodysplasia.[37]

- Cytogenetics or chromosomal studies: This is ideally performed on the bone marrow aspirate. Conventional cytogenetics requires a fresh specimen since live cells are induced to enter metaphase to allow chromosomes to be seen.

- Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization testing, usually ordered together with conventional cytogenetic testing, offers rapid detection of several chromosome abnormalities associated with MDS, including del 5q, −7, +8, and del 20q.

- Virtual karyotyping can be done for MDS,[38] which uses computational tools to construct the karyogram from disrupted DNA. Virtual karyotyping does not require cell culture and has a dramatically higher resolution than conventional cytogenetics, but cannot detect balanced translocations.

- Flow cytometry is helpful to identify blasts, abnormal myeloid maturation, and establish the presence of any lymphoproliferative disorder in the marrow.

- Testing for copper deficiency should not be overlooked, as it can morphologically resemble MDS in bone-marrow biopsies.[39] Risk factors for copper deficiency include bariatric surgery, zinc supplementation, and celiac disease.[40]

The features generally used to define an MDS are blood cytopenias, ineffective hematopoiesis, dyserythropoiesis, dysgranulopoiesis, dysmegakaropoiesis, and increased myeloblasts.[citation needed]

Dysplasia can affect all three lineages seen in the bone marrow. The best way to diagnose dysplasia is by morphology and special stains (PAS) used on the bone marrow aspirate and peripheral blood smear. Dysplasia in the myeloid series is defined by:

- Granulocytic series[citation needed]:

- Hypersegmented neutrophils (also seen in vit B12/folate deficiency)

- Hyposegmented neutrophils (pseudo Pelger-Huet)

- Hypogranular neutrophils or pseudo Chediak-Higashi (large azurophilic granules)

- Auer rods – automatically RAEB II (if blast count < 5% in the peripheral blood and < 10% in the bone marrow aspirate); also note Auer rods may be seen in mature neutrophils in AML with translocation t(8;21)

- Dimorphic granules (basophilic and eosinophilic granules) within eosinophils

- Erythroid series[citation needed]:

- Binucleated erythroid precursors and karyorrhexis

- Erythroid nuclear budding

- Erythroid nuclear strings or internuclear bridging (also seen in congenital dyserythropoietic anemias)

- Loss of e-cadherin in normoblasts is a sign of aberrancy.

- PAS (globular in vacuoles or diffuse cytoplasmic staining) within erythroid precursors in the bone marrow aspirate (has no bearing on paraffin-fixed bone-marrow biopsy). Note: one can see PAS vacuolar positivity in L1 and L2 blasts (FAB classification; the L1 and L2 nomenclature is not used in the WHO classification)

- Ringed sideroblasts (10 or more iron granules encircling one-third or more of the nucleus) seen on Perls' Prussian blue iron stain (>15% ringed sideroblasts when counted among red cell precursors for refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts)

- Megakaryocytic series (can be the most subjective)[citation needed]:

- Hyposegmented nuclear features in platelet-producing megakaryocytes (lack of lobation)

- Hypersegmented (osteoclastic appearing) megakaryocytes

- Ballooning of the platelets (seen with interference contrast microscopy)

On the bone-marrow biopsy, high-grade dysplasia (RAEB-I and RAEB-II) may show atypical localization of immature precursors, which are islands of immature precursors cells (myeloblasts and promyelocytes) localized to the center of the intertrabecular space rather than adjacent to the trabeculae or surrounding arterioles. This morphology can be difficult to differentiate from treated leukemia and recovering immature normal marrow elements. Also, topographic alteration of the nucleated erythroid cells can be seen in early myelodysplasia (RA and RARS), where normoblasts are seen next to bony trabeculae instead of forming normal interstitially placed erythroid islands.[citation needed]

Classification

[edit]World Health Organization and International Consensus Classification

[edit]In the late 1990s, a group of pathologists and clinicians working under the World Health Organization (WHO) modified this classification, introducing several new disease categories and eliminating others. In 2008, 2016, and 2022, the WHO developed new classification schemes that incorporated genetic findings (5q-) alongside morphology of the cells in the peripheral blood and bone marrow. As of 2024, the WHO 5th edition and International Consensus Classification (ICC)[41] systems are both actively in use.[11]

The list of dysplastic syndromes under the 2008 WHO system included the following:

| Myelodysplastic syndrome | Description and WHO 5th ed. counterparts |

|---|---|

| Refractory cytopenia with unilineage dysplasia | Refractory anemia, Refractory neutropenia, and Refractory thrombocytopenia. Revised to MDS with LB (low blasts) |

| Refractory anemia with ringed sideroblasts (RARS) | Revised to MDS with LB and RS or MDS with LB and SF3B1 mutation

Includes the subset Thrombocytosis (MDS/MPN-T) myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative disorder |

| Refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia (RCMD) | Includes the subset Refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia and ring sideroblasts (RCMD-RS). Revised to MDS with LB. |

| Refractory anemia with excess blasts I and II | RAEB was divided into RAEB-I (5–9% blasts) and RAEB-II (10–19%) blasts, which has a poorer prognosis than RAEB-I.

Revised to MDS with IB1 and MDS with IB2. (Increased Blasts) |

| 5q- syndrome | Typically seen in older women with normal or high platelet counts and isolated deletions of the long arm of chromosome 5 in bone marrow cells. |

| Myelodysplasia unclassifiable | Seen in those cases of megakaryocyte dysplasia with fibrosis and others. |

| Refractory cytopenia of childhood (dysplasia in childhood) | – |

MDS with single lineage dysplasia

[edit]MDS may present with isolated neutropenia or thrombocytopenia without anemia and with dysplastic changes confined to a single lineage. This is called MDS-Low Blasts in the WHO 5th ed.[11]

MDS with increased blood counts

[edit]Patients with MDS occasionally present with leukocytosis or thrombocytosis instead of the usual cytopenia. This may represent overlap syndromes with myeloproliferative neoplasms.[11]

MDS unclassifiable

[edit]Most cases of unclassifiable MDS from the 2008 WHO version would be considered Clonal Cytopenias of Undetermined Significance (CCUS) by the WHO 5th ed.[11] CCUS is defined[42] as:

- One or more somatic mutations otherwise found in patients with myeloid neoplasms detected in bone marrow or peripheral blood cells with an allele burden of ≥ 2%

- Persistent cytopenia (≥ 4 months) in one or more peripheral blood cell lineages

- Diagnostic criteria of myeloid neoplasm not fulfilled

- All other causes of cytopenia and molecular aberration excluded

New categories in WHO 5th ed.

[edit]Hypoplastic MDS, MDS with fibrosis, MDS with bi-allelic TP53 inactivation, and CCUS were added to the WHO 5th ed.[11] Another subtype called Myeloid neoplasms with germ line predisposition and organ dysfunction includes CEBPA/DDX41/RUNX1 disorders, GATA2 deficiency and SAMD9/9L syndromes.[16]

Management

[edit]The goals of therapy are to control symptoms, improve quality of life, improve overall survival, and decrease progression to AML.

The IPSS scoring system can help guide therapy for patients with MDS.[43][44] In those with low risk MDS (designated by an IPSS score less than 3.5), no disease specific treatment has been found to be helpful and treatment is focused on supportive care by maintaining blood counts.[36] Erythrostimulating agents such as darbepoetin alfa or erythropoietin may be used to raise the red blood cell count. The mean duration of response to erythrostimulating agents is 8-23 months, and the response rate is about 39% (with a response defined as a 1 mg/dL rise in the hemoglobin level or a person not requiring a transfusion).[36]

Romiplostim and eltrombopag are thrombopoietin receptor agonists which act on megakaryocytes (platelet precursor cells) to increase platelet production. They are used to increase platelet counts and have been shown to reduce the need for platelet transfusions.[36] However, the two drugs increase the risk of progression to AML, so they are not used in MDS with excess blasts.[36]

For those with high risk MDS (characterized by an IPSS score greater than 3.5), the hypomethylating agent azacitidine showed increased survival compared to standard care (supportive care, cytarabine or chemotherapy) and is considered the standard of care.[36][45] Azacitidine had increased survival (24 months vs 15 months) and higher rates of partial or complete therapeutic response (29% vs 12%) as compared to conventional care.[30] The hypomethylating agent decitabine has shown a similar survival benefit to azacitidine and has a response rate as high as 43%.[36][46][47][48] Decitabine is available in combination with cedazuridine as Decitabine/cedazuridine (Inqovi) is a fixed-dosed combination medication for the treatment of adults with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML).[49]

Lenalidomide is effective in reducing red blood cell transfusion requirement in patients with the chromosome 5q deletion subtype (5q- syndrome) of MDS, and the median duration of response is greater than 2 years.[50][36]

Luspatercept is a TGFβ ligand that acts to decrease SMAD2 and SMAD3 signaling involved in erythropoeisis and may be used in MDS with anemia that is not responsive to erythrocyte-stimulating agents or mild MDS with ring sideroblasts. Luspatercept was shown to decrease the need for transfusions, and this effect lasted for a median of 30.6 weeks.[51][36][52]

HLA-matched allogeneic stem cell transplantation, particularly in younger (i.e., less than 40 years of age) and more severely affected patients, offers the potential for curative therapy. The success of bone marrow transplantation has been found to correlate with severity of MDS as determined by the IPSS score, with patients having a more favorable IPSS score tend to have a more favorable outcome with transplantation.[53]

Iron levels

[edit]Iron overload may develop in MDS as a result of repeated RBC transfusions, which are a major part of the supportive care for anemic MDS patients. Although the specific therapies patients receive may obviate the need for RBC transfusion, many MDS patients may not respond to these treatments, and thus may develop secondary hemochromatosis due to iron overload from repeated transfusions. Patients with chronic iron overload can have iron deposits in their liver, heart, and endocrine glands.[citation needed]

For patients requiring many transfusions, serum ferritin levels, the number of transfusions received, and associated organ dysfunction (heart, liver, and pancreas) should be monitored to determine iron levels. The goal is to maintain ferritin levels to < 1000 µg/L.[citation needed] Currently, two iron chelators are available in the US, deferoxamine for intravenous use and deferasirox for oral use. A third chelating agent is available, deferiprone, but it has limited utility in MDS patients because of a major side effect of neutropenia.[54]

Reversal of some of the consequences of iron overload in MDS by iron chelation therapy has been shown. Iron overload not only leads to organ damage but also induces genomic instability and modifies the hematopoietic niche, favoring progression to acute leukemia. Chelation therapy should be considered to decrease iron overload in selected MDS patients.[54] Although deferasirox is generally well tolerated (other than episodes of gastrointestinal distress and kidney dysfunction), it is associated with a rare risk of kidney failure or liver failure. Due to these risks, close monitoring is required.[citation needed]

Prognosis

[edit]The outlook in MDS is variable, with about 30% of patients progressing to refractory AML. Low-risk MDS (which is associated with favorable genetic variants, decreased myeloblastic cells [less than 5% blasts], less severe anemia, thrombocytopenia, or neutropenia or lower International Prognostic Scoring System scores) is associated with a life expectancy of 3–10 years. Whereas high-risk MDS is associated with a life expectancy of less than 3 years.[36]

Stem-cell transplantation offers a possible cure, with survival rates of 50% at 3 years, although older patients do poorly.[55]

Indicators of a good prognosis: Younger age; normal or moderately reduced neutrophil or platelet counts; low blast counts in the bone marrow (< 20%) and no blasts in the blood; no Auer rods; ringed sideroblasts; normal or mixed karyotypes without complex chromosome abnormalities; and in vitro marrow culture with a nonleukemic growth pattern

Indicators of a poor prognosis: Advanced age; severe neutropenia or thrombocytopenia; high blast count in the bone marrow (20–29%) or blasts in the blood; Auer rods; absence of ringed sideroblasts; abnormal localization or immature granulocyte precursors in bone marrow section; completely or mostly abnormal karyotypes, or complex marrow chromosome abnormalities and in vitro bone marrow culture with a leukemic growth pattern

Karyotype prognostic factors:

- Good: normal, -Y, del(5q), del(20q)

- Intermediate or variable: +8, other single or double anomalies

- Poor: complex (>3 chromosomal aberrations); chromosome 7 anomalies[56]

Cytogenetic abnormalities can be detected by conventional cytogenetics, a FISH panel for MDS, or virtual karyotype.

The best prognosis is seen with RA and RARS, where some nontransplant patients live more than a decade (typical is on the order of three to five years, although long-term remission is possible if a bone-marrow transplant is successful). The worst outlook is with RAEB-T, where the mean life expectancy is less than one year. About one-quarter of patients develop overt leukemia. The others die of complications of low blood count or unrelated diseases. The International Prognostic Scoring System is the most commonly used tool for determining the prognosis of MDS, first published in Blood in 1997,[57] then revised to IPSS-R and IPSS-M.[11] This system takes into account the percentage of blasts in the marrow, cytogenetics, and number of cytopenias, as well as molecular features in the case of IPSS-M. Other prognostic tools include the 2007 WHO Prognostic Scoring System (WPSS), the MDA-LR (MD Anderson Lower-Risk MDS Prognostic Scoring System), EuroMDS, and the Cleveland Clinic Foundation/Munich Leukemia Laboratory scoring systems.[58]

Genetic markers

[edit]The IPSS-M incorporates 31 somatic genes in its risk stratification model. IPSS-M determined that multihit TP53 mutations, FLT3 mutations, and partial tandem duplication mutations of KMT2A (MLL) were strong predictors of adverse outcomes. Some SF3B1 mutations were associated with favorable outcomes, whereas certain genetic subsets of SF3B1 mutations were not.[11] In low-risk MDS, IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are associated with worsened survival.[29]

Epidemiology

[edit]The exact number of people with MDS is not known because it can go undiagnosed, and no tracking of the syndrome is mandated. Some estimates are on the order of 10,000 to 20,000 new cases each year in the United States alone. The number of new cases each year is probably increasing as the average age of the population increases, and some authors propose that the number of new cases in those over 70 may be as high as 15 per 100,000 per year.[59]

The typical age at diagnosis of MDS is between 60 and 75 years; a few people are younger than 50, and diagnoses are rare in children. Males are slightly more commonly affected than females.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Since the early 20th century, some people with acute myelogenous leukemia have been recognized to have a preceding period of anemia and abnormal blood cell production. These conditions were grouped with other diseases under the term "refractory anemia". The first description of "preleukemia" as a specific entity was published in 1953 by Block et al.[60] The early identification, characterization and classification of this disorder were problematical, and the syndrome went by many names until the 1976 FAB classification was published and popularized the term MDS.[citation needed]

French-American-British (FAB) classification

[edit]In 1974 and 1975, a group of pathologists from France, the US, and Britain produced the first widely used classification of these diseases. This French-American-British classification was published in 1976,[61] and revised in 1982. It was used by pathologists and clinicians for almost 20 years. Cases were classified into five categories:

| ICD-O | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| M9980/3 | Refractory anemia (RA) | characterized by less than 5% primitive blood cells (myeloblasts) in the bone marrow and pathological abnormalities primarily seen in red cell precursors |

| M9982/3 | Refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts (RARS) | also characterized by less than 5% myeloblasts in the bone marrow, but distinguished by the presence of 15% or greater of red cell precursors in the marrow, being abnormal iron-stuffed cells called "ringed sideroblasts" |

| M9983/3 | Refractory anemia with excess blasts (RAEB) | characterized by 5–19% myeloblasts in the marrow |

| M9984/3 | Refractory anemia with excess blasts in transformation (RAEB-T) | characterized by 5–19% myeloblasts in the marrow (>20% blasts is defined as acute myeloid leukemia) |

| M9945/3 | Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), not to be confused with chronic myelogenous leukemia or CML | characterized by less than 20% myeloblasts in the bone marrow and greater than 1*109/L monocytes (a type of white blood cell) circulating in the peripheral blood. |

(A table comparing these is available from the Cleveland Clinic.[62])

People with MDS

[edit]- Michael Brecker, musician[63]

- Laurentino Cortizo, the President of Panama[64]

- Roald Dahl, writer[65]

- Nora Ephron, journalist, writer, and filmmaker

- Pat Hingle, actor[66]

- Paul Motian, musician[67]

- Amrish Puri, actor[68]

- Carl Sagan, astrophysicist[69]

- Susan Sontag, author[70]

- Norm Macdonald, comedian[71]

References

[edit]- ^ "Myelodysplasia". SEER. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ "Myelodysplastic Syndromes". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Myelodysplastic Syndromes Treatment (PDQ®) – Patient Version". NCI. 12 August 2015. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ a b c Germing U, Kobbe G, Haas R, Gattermann N (November 2013). "Myelodysplastic syndromes: diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 110 (46): 783–90. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2013.0783. PMC 3855821. PMID 24300826.

- ^ a b Hong WK, Holland JF (2010). Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine (8th ed.). PMPH-USA. p. 1544. ISBN 978-1-60795-014-1. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016.

- ^ "Anemia: Overview". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ "Neutropenia". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ Myelodysplastic Syndrome. White Plains, NY: The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. 2001. p. 24. OCLC 64551506.

- ^ "Thrombocytopenia". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ "Myelodysplastic Syndromes". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hasserjian RP, Germing U, Malcovati L (December 2023). "Diagnosis and classification of myelodysplastic syndromes". Blood. 142 (26): 2247–57. doi:10.1182/blood.2023020078. PMID 37774372.

- ^ Patnaik MM, Lasho T (4 December 2020). "Evidence-Based Minireview: Myelodysplastic syndrome/myeloproliferative neoplasm overlap syndromes: a focused review". Hematology. 2020 (1): 460–4. doi:10.1182/hematology.2020000163. PMC 7727594. PMID 33275673.

- ^ Sperling AS, Leventhal M, Gibson CJ, Ebert BL, Steensma DP (March 2020). "Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) occurring in Agent Orange exposed individuals carry a mutational spectrum similar to that of de novo MDS". Leuk Lymphoma. 61 (3): 728–731. doi:10.1080/10428194.2019.1689394. PMC 7268906. PMID 31714164.

- ^ Iwanaga M, Hsu WL, Soda M, Takasaki Y, Tawara M, Joh T, et al. (February 2011). "Risk of myelodysplastic syndromes in people exposed to ionizing radiation: a retrospective cohort study of Nagasaki atomic bomb survivors". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (4): 428–34. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.31.3080. PMID 21149671.

- ^ a b Dokal I, Vulliamy T (August 2010). "Inherited bone marrow failure syndromes". Haematologica. 95 (8): 1236–40. doi:10.3324/haematol.2010.025619. PMC 2913069. PMID 20675743.

- ^ a b Hall T, Gurbuxani S, Crispino JD (May 2024). "Malignant progression of preleukemic disorders". Blood. 143 (22): 2245–55. doi:10.1182/blood.2023020817. PMC 11181356. PMID 38498034.

- ^ Bejar R (December 2018). "What biologic factors predict for transformation to AML?". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Haematology. 31 (4): 341–5. doi:10.1016/j.beha.2018.10.002. PMID 30466744. S2CID 53712886.

- ^ Rasel M, Mahboobi SK (2022), "Transfusion Iron Overload", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32965817, retrieved 3 February 2022

- ^ Wolach O, Stone RM (2015). "How I treat mixed-phenotype acute leukemia". Blood. 125 (16): 2477–85. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-10-551465. PMID 25605373.

- ^ Cazzola M, Invernizzi R, Bergamaschi G, Levi S, Corsi B, Travaglino E, et al. (March 2003). "Mitochondrial ferritin expression in erythroid cells from patients with sideroblastic anemia". Blood. 101 (5): 1996–2000. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-07-2006. PMID 12406866. S2CID 5729203.

- ^ Zhou T, Chen P, Gu J, Bishop AJ, Scott LM, Hasty P, et al. (January 2015). "Potential relationship between inadequate response to DNA damage and development of myelodysplastic syndrome". Int J Mol Sci. 16 (1): 966–89. doi:10.3390/ijms16010966. PMC 4307285. PMID 25569081.

- ^ Zhou T, Hasty P, Walter CA, Bishop AJ, Scott LM, Rebel VI (August 2013). "Myelodysplastic syndrome: an inability to appropriately respond to damaged DNA?". Exp Hematol. 41 (8): 665–74. doi:10.1016/j.exphem.2013.04.008. PMC 3729593. PMID 23643835.

- ^ a b Jankowska AM, Gondek LP, Szpurka H, Nearman ZP, Tiu RV, Maciejewski JP (March 2008). "Base excision repair dysfunction in a subgroup of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome". Leukemia. 22 (3): 551–8. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2405055. PMID 18059482.

- ^ Bunn HF (November 1986). "5q- and disordered haematopoiesis". Clinics in Haematology. 15 (4): 1023–35. PMID 3552346.

- ^ Van den Berghe H, Cassiman JJ, David G, Fryns JP, Michaux JL, Sokal G (October 1974). "Distinct haematological disorder with deletion of long arm of no. 5 chromosome". Nature. 251 (5474): 437–38. Bibcode:1974Natur.251..437V. doi:10.1038/251437a0. PMID 4421285. S2CID 4286311.

- ^ List A, Kurtin S, Roe DJ, Buresh A, Mahadevan D, Fuchs D, et al. (February 2005). "Efficacy of lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromes". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (6): 549–57. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041668. PMID 15703420.

- ^ Rozovski U, Keating M, Estrov Z (July 2013). "The significance of spliceosome mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia". Leuk Lymphoma. 54 (7): 1364–6. doi:10.3109/10428194.2012.742528. PMC 4176818. PMID 23270583.

- ^ Molenaar RJ, Radivoyevitch T, Maciejewski JP, van Noorden CJ, Bleeker FE (December 2014). "The driver and passenger effects of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations in oncogenesis and survival prolongation". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer. 1846 (2): 326–41. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.05.004. PMID 24880135.

- ^ a b c Molenaar RJ, Thota S, Nagata Y, Patel B, Clemente M, Przychodzen B, et al. (November 2015). "Clinical and biological implications of ancestral and non-ancestral IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in myeloid neoplasms". Leukemia. 29 (11): 2134–42. doi:10.1038/leu.2015.91. PMC 5821256. PMID 25836588.

- ^ a b c Crispino JD, Horwitz MS (April 2017). "GATA factor mutations in hematologic disease". Blood. 129 (15): 2103–10. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-09-687889. PMC 5391620. PMID 28179280.

- ^ Hirabayashi S, Wlodarski MW, Kozyra E, Niemeyer CM (August 2017). "Heterogeneity of GATA2-related myeloid neoplasms". International Journal of Hematology. 106 (2): 175–82. doi:10.1007/s12185-017-2285-2. PMID 28643018.

- ^ Takasaki K, Chou ST (2024). "GATA1 in Normal and Pathologic Megakaryopoiesis and Platelet Development". Transcription factors in blood cell development. Adv Exp Med Biol. Vol. 1459. pp. 261–287. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-62731-6_12. ISBN 978-3-031-62730-9. PMID 39017848.

- ^ Bhatnagar N, Nizery L, Tunstall O, Vyas P, Roberts I (October 2016). "Transient Abnormal Myelopoiesis and AML in Down Syndrome: an Update". Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports. 11 (5): 333–41. doi:10.1007/s11899-016-0338-x. PMC 5031718. PMID 27510823.

- ^ Seewald L, Taub JW, Maloney KW, McCabe ER (September 2012). "Acute leukemias in children with Down syndrome". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 107 (1–2): 25–30. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.07.011. PMID 22867885.

- ^ Mecham B, Drissi W, Brummell G, Dadi N, Martin DE (May 2024). "Severe B12 Deficiency Causing a Maturation Defect Mimicking Myelodysplastic Syndrome With Excess Blasts". Cureus. 16 (5) e60837. doi:10.7759/cureus.60837. PMC 11191413. PMID 38910768.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sekeres MA, Taylor J (6 September 2022). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Myelodysplastic Syndromes: A Review". JAMA. 328 (9): 872–880. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.14578. PMID 36066514.

- ^ "Rudhiram Hematology Clinic - Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ Gondek LP, Tiu R, O'Keefe CL, Sekeres MA, Theil KS, Maciejewski JP (February 2008). "Chromosomal lesions and uniparental disomy detected by SNP arrays in MDS, MDS/MPD, and MDS-derived AML". Blood. 111 (3): 1534–42. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-05-092304. PMC 2214746. PMID 17954704.

- ^ Huff JD, Keung YK, Thakuri M, Beaty MW, Hurd DD, Owen J, et al. (July 2007). "Copper deficiency causes reversible myelodysplasia". American Journal of Hematology. 82 (7): 625–30. doi:10.1002/ajh.20864. PMID 17236184. S2CID 44398996.

- ^ Luo T, Zurko J, Astle J, Shah NN (2021). "Mimicking Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Importance of Differential Diagnosis". Case Rep Hematol. 2021 9661765. doi:10.1155/2021/9661765. PMC 8648467. PMID 34881068.

- ^ Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian RP, Borowitz MJ, Calvo KR, Kvasnicka HM, et al. (September 2022). "International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data". Blood. 140 (11): 1200–28. doi:10.1182/blood.2022015850. PMC 9479031. PMID 35767897.

- ^ DeZern AE, Malcovati L, Ebert BL (January 2019). "CHIP, CCUS, and Other Acronyms: Definition, Implications, and Impact on Practice". Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 39 (39): 400–410. doi:10.1200/EDBK_239083. PMID 31099654.

- ^ Cutler CS, Lee SJ, Greenberg P, Deeg HJ, Pérez WS, Anasetti C, et al. (July 2004). "A decision analysis of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for the myelodysplastic syndromes: delayed transplantation for low-risk myelodysplasia is associated with improved outcome". Blood. 104 (2): 579–85. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-01-0338. PMID 15039286. S2CID 17907118.

- ^ Bernard E, Tuechler H, Greenberg PL, Hasserjian RP, Arango Ossa JE, Nannya Y, et al. (July 2022). "Molecular International Prognostic Scoring System for Myelodysplastic Syndromes". NEJM Evid. 1 (7) EVIDoa2200008. doi:10.1056/EVIDoa2200008. PMID 38319256.

- ^ Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, Santini V, Finelli C, Giagounidis A, et al. (March 2009). "Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomised, open-label, phase III study". The Lancet Oncology. 10 (3): 223–232. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70003-8. PMC 4086808. PMID 19230772.

- ^ Kantarjian HM, O'Brien S, Shan J, Aribi A, Garcia-Manero G, Jabbour E, et al. (January 2007). "Update of the decitabine experience in higher risk myelodysplastic syndrome and analysis of prognostic factors associated with outcome". Cancer. 109 (2): 265–73. doi:10.1002/cncr.22376. PMID 17133405. S2CID 41205800.

- ^ Kantarjian H, Issa JP, Rosenfeld CS, Bennett JM, Albitar M, DiPersio J, et al. (April 2006). "Decitabine improves patient outcomes in myelodysplastic syndromes: results of a phase III randomized study". Cancer. 106 (8): 1794–803. doi:10.1002/cncr.21792. PMID 16532500. S2CID 9556660.

- ^ Kantarjian H, Oki Y, Garcia-Manero G, Huang X, O'Brien S, Cortes J, et al. (January 2007). "Results of a randomized study of 3 schedules of low-dose decitabine in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia". Blood. 109 (1): 52–57. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-05-021162. PMID 16882708.

- ^ "FDA Approves New Therapy for Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) That Can Be Taken at Home". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 7 July 2020. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ List A, Dewald G, Bennett J, Giagounidis A, Raza A, Feldman E, et al. (October 2006). "Lenalidomide in the myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion". The New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (14): 1456–65. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061292. PMID 17021321.

- ^ Fenaux P, Platzbecker U, Mufti GJ (9 January 2020). "Luspatercept in Patients with Lower-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndromes". New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (2): 140–151. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1908892. hdl:2158/1193441. PMID 31914241.

- ^ Hellström-Lindberg ES, Kröger N (December 2023). "Clinical decision-making and treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes". Blood. 142 (26): 2268–81. doi:10.1182/blood.2023020079. PMID 37874917.

- ^ Oosterveld M, Wittebol SH, Lemmens WA, Kiemeney BA, Catik A, Muus P, et al. (October 2003). "The impact of intensive antileukaemic treatment strategies on prognosis of myelodysplastic syndrome patients aged less than 61 years according to International Prognostic Scoring System risk groups". British Journal of Haematology. 123 (1): 81–89. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04544.x. PMID 14510946. S2CID 24037285.

- ^ a b Parisi S, Finelli C (December 2021). "Prognostic Factors and Clinical Considerations for Iron Chelation Therapy in Myelodysplastic Syndrome Patients". Journal of Blood Medicine. 12: 1019–30. doi:10.2147/JBM.S287876. PMC 8651046. PMID 34887690.

- ^ Kasper, Dennis L, Braunwald, Eugene, Fauci, Anthony, et al. (2005). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (16th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 625. ISBN 978-0-07-139140-5.

- ^ Solé F, Espinet B, Sanz GF, Cervera J, Calasanz MJ, Luño E, et al. (February 2000). "Incidence, characterization and prognostic significance of chromosomal abnormalities in 640 patients with primary myelodysplastic syndromes. Grupo Cooperativo Español de Citogenética Hematológica". British Journal of Haematology. 108 (2): 346–56. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01868.x. PMID 10691865. S2CID 10149222.

- ^ Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, Fenaux P, Morel P, Sanz G, et al. (March 1997). "International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes". Blood. 89 (6): 2079–88. doi:10.1182/blood.V89.6.2079. PMID 9058730.

- ^ DeZern AE, Greenberg PL (December 2023). "The trajectory of prognostication and risk stratification for patients with myelodysplastic syndromes". Blood. 142 (26): 2258–67. doi:10.1182/blood.2023020081. PMID 37562001.

- ^ Aul C, Giagounidis A, Germing U (June 2001). "Epidemiological features of myelodysplastic syndromes: results from regional cancer surveys and hospital-based statistics". International Journal of Hematology. 73 (4): 405–10. doi:10.1007/BF02994001. PMID 11503953. S2CID 24340387.

- ^ Block M, Jacobson LO, Bethard WF (July 1953). "Preleukemic acute human leukemia". Journal of the American Medical Association. 152 (11): 1018–28. doi:10.1001/jama.1953.03690110032010. PMID 13052490.

- ^ Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DA, Gralnick HR, et al. (August 1976). "Proposals for the classification of the acute leukaemias. French-American-British (FAB) co-operative group". British Journal of Haematology. 33 (4): 451–58. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.1976.tb03563.x. PMID 188440. S2CID 9985915.

- ^ "Table 1: French-American-British (FAB) Classification of MDS". Archived from the original on 17 January 2006.

- ^ "Saxophonist Brecker dies from MDS". Variety. 14 January 2007. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- ^ "Panama says President Cortizo still in remission from rare blood disorder". Reuters. 6 December 2023. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ "Deaths England and Wales 1984–2006". Findmypast.com. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ^ Staff J (4 January 2009). "Veteran actor Pat Hingle dies at 84 in NC home". Winston-Salem Journal.

- ^ McClellan D (24 November 2011). "Paul Motian dies at 80; jazz drummer and composer". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India – Main News". Tribuneindia.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ "Remembering Carl Sagan". Universe Today. 9 November 2012. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ "Illness as More Than Metaphor". The New York Times Magazine. 4 December 2005. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ Edgers G (29 May 2022). "Norm Macdonald had one last secret". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 May 2025.

External links

[edit]- Fenaux P, Haase D, Sanz GF, Santini V, Buske C (September 2014). "Myelodysplastic syndromes: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up". Ann Oncol. 25 (Suppl 3): III57 – III69. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu180. hdl:2158/1078046. PMID 25185242.

Myelodysplastic syndrome

View on GrokipediaClinical Features

Signs and Symptoms

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) often presents with symptoms arising from peripheral blood cytopenias, which result from ineffective hematopoiesis in the bone marrow. Many patients are asymptomatic in the early stages and are diagnosed incidentally during routine blood tests, such as complete blood counts performed for unrelated reasons.[5][1] Anemia, the most common cytopenia in MDS, leads to fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath, and pallor due to reduced oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.[5][1] Thrombocytopenia manifests as easy bruising, petechiae (small red or purple spots on the skin caused by minor bleeding), and increased bleeding tendencies, including epistaxis (nosebleeds) or gingival bleeding.[5][9] Neutropenia predisposes patients to recurrent infections, fever, and a heightened risk of sepsis, often presenting as frequent or prolonged episodes of illness such as pneumonia or urinary tract infections.[5][8] Less common findings include splenomegaly, which occurs in approximately 5–15% of patients with pure MDS and is enriched for adverse mutations such as ASXL1, RUNX1, and EZH2; it suggests marrow stress or fibrosis with extramedullary hematopoiesis and is more typical of MDS/MPN overlap syndromes or primary myelofibrosis.[10] Less common symptoms include unexplained weight loss, which may occur in more advanced cases.[11]Complications

One of the most significant complications of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is its potential progression to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), occurring in approximately 30% of cases overall, with rates reaching up to 40% in higher-risk subtypes characterized by increased bone marrow blasts or adverse cytogenetic features.[12][13] This transformation typically arises from the accumulation of genetic mutations in hematopoietic stem cells, leading to a more aggressive clonal expansion.[14] Chronic anemia and thrombocytopenia in MDS often necessitate repeated red blood cell transfusions, resulting in iron overload that can deposit in vital organs such as the heart, liver, and endocrine glands, causing cardiomyopathy, cirrhosis, diabetes, and hypogonadism.[15][16] This secondary hemochromatosis exacerbates morbidity and mortality, particularly in transfusion-dependent patients without chelation therapy.[17] Persistent neutropenia predisposes MDS patients to severe bacterial, fungal, and viral infections, which account for a substantial portion of non-leukemic deaths due to impaired immune function and mucosal barriers.[18][19] Common sites include the lungs, skin, and gastrointestinal tract, with chronic low-grade neutropenia amplifying the risk of sepsis and multi-organ failure.[20] Thrombocytopenia can lead to bleeding complications ranging from mucocutaneous petechiae to life-threatening hemorrhages in critical areas like the gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system, or retina, affecting up to 10% of patients severely.[21][20] These events are often exacerbated by concurrent platelet dysfunction, increasing the likelihood of spontaneous or trauma-induced bleeding in vital organs.[19] Less commonly, MDS is associated with autoimmune phenomena, such as hemolytic anemia, vasculitis, or Sweet syndrome, occurring in 10-20% of cases and potentially driven by dysregulated immune responses to clonal hematopoiesis.[22] Additionally, there is an elevated risk of secondary solid tumors, including breast, lung, and prostate cancers, linked to shared genetic predispositions or prior exposures, though the absolute incidence remains low compared to hematologic progression.[23]Etiology and Risk Factors

Causes

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is idiopathic in the majority of cases, with no identifiable cause despite extensive evaluation.[5][1] A significant proportion of MDS cases, approximately 10-20%, arise as therapy-related MDS (t-MDS) following prior exposure to chemotherapy or radiation therapy for other malignancies.[24][25] Alkylating agents, such as cyclophosphamide, are commonly implicated in t-MDS, typically manifesting 5-7 years after exposure and often associated with complex cytogenetic abnormalities.[6] Topoisomerase II inhibitors, including etoposide and doxorubicin, also contribute to t-MDS pathogenesis, frequently leading to balanced translocations like 11q23 rearrangements.[6] Environmental and occupational exposures represent another established causal pathway for MDS. Benzene, a solvent found in industrial settings, has been directly linked to MDS development through its genotoxic effects on hematopoietic stem cells.[6] Similarly, prolonged contact with pesticides, fertilizers, or heavy metals such as mercury and lead increases MDS risk, particularly in agricultural or manufacturing workers.[26][1] Certain inherited genetic predisposition syndromes confer susceptibility to MDS. Fanconi anemia, characterized by DNA repair defects, heightens the lifetime risk of developing MDS due to genomic instability in bone marrow progenitors.[6] Down syndrome (trisomy 21) is another well-documented predisposition, where the extra chromosome 21 disrupts normal hematopoiesis and predisposes individuals to transient myeloproliferative disorders that can evolve into MDS.[6] Iatrogenic causes, beyond cytotoxic therapies, include prolonged use of immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, which has been associated with MDS emergence through induction of chromosomal aberrations in hematopoietic cells.[6]Risk Factors

Advanced age is the most significant demographic risk factor for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), with approximately 86% of cases occurring in individuals aged 60 years or older.[27] The median age at diagnosis is typically in the 70s, reflecting the disease's strong association with aging bone marrow stem cell dysfunction.[28] MDS also exhibits a male predominance, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 1.5:1, potentially influenced by higher rates of exposure to risk factors such as smoking among men.[29] Among modifiable lifestyle factors, cigarette smoking has been consistently linked to increased MDS risk, with meta-analyses showing an odds ratio of about 1.45 for ever-smokers compared to non-smokers, attributed to carcinogenic compounds in tobacco that damage hematopoietic stem cells.[30] Evidence regarding alcohol consumption is mixed; some studies suggest a dose-dependent increase in risk, while others, including larger cohort analyses, find no significant association or even a potential protective effect from moderate intake.[31][32] Prior hematologic disorders elevate MDS susceptibility, particularly in cases where aplastic anemia evolves into clonal hematopoiesis; up to 15% of acquired aplastic anemia patients may progress to MDS within 10 years due to shared pathogenic mechanisms involving immune dysregulation and genetic instability.[33] Familial history plays a role in rare hereditary forms of MDS, often linked to germline mutations in genes such as GATA2, which predispose affected families to MDS or acute myeloid leukemia through haploinsufficiency and impaired hematopoiesis.[34] Chemical exposures, such as to benzene, represent additional environmental risks that may contribute to MDS development.[28]Pathophysiology

Dysplasia and Ineffective Hematopoiesis

Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are characterized by morphologic dysplasia in bone marrow precursors across one or more myeloid lineages, reflecting abnormal cellular maturation and differentiation.[6] In the erythroid lineage, megaloblastoid changes manifest as enlarged, immature-appearing erythroblasts with asynchronous nuclear and cytoplasmic development, contributing to defective red blood cell production.[6] Dysgranulopoiesis often includes the pseudo-Pelger-Huët anomaly, where neutrophils exhibit hyposegmented, bilobed nuclei and hypogranular cytoplasm, impairing their functionality.[6] Ring sideroblasts, a hallmark of certain MDS subtypes, appear as erythroid precursors with iron-laden mitochondria encircling at least one-third of the nucleus, detectable by Prussian blue staining and indicative of mitochondrial dysfunction in heme synthesis.[6] These dysplastic features arise from intrinsic defects in hematopoietic progenitors, leading to multilineage involvement in many cases.[35] A central mechanism in MDS pathophysiology is ineffective hematopoiesis, particularly ineffective erythropoiesis, where erythroid progenitors undergo accelerated intramedullary apoptosis, resulting in reduced mature cell output despite initial proliferation.[35] This apoptosis is mediated by upregulated death receptors such as Fas and TRAIL, as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, predominantly in low-risk MDS, causing premature cell death within the bone marrow.[36] Granulopoiesis is similarly impaired, with dysplastic neutrophils showing reduced maturation and survival, while megakaryopoiesis features micromegakaryocytes—small, hypolobated cells with abnormal nuclear features—that fail to produce adequate platelets.[6] These processes collectively disrupt normal blood cell production, exacerbated by clonal expansion of mutated hematopoietic stem cells that outcompete and displace healthy progenitors, further suppressing effective hematopoiesis.[35] Despite these defects, the bone marrow in MDS is typically hypercellular or normocellular, reflecting compensatory proliferation of abnormal clones that paradoxically leads to peripheral blood cytopenias, including anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.[6] This discordance between marrow cellularity and peripheral counts underscores the inefficiency of the dysplastic process, where increased progenitor turnover fails to yield functional cells due to ongoing apoptosis and maturation blocks.[36] Genetic alterations in stem cells drive this clonal dominance, but the phenotypic dysplasia and functional impairments remain the proximate causes of cytopenias.[35]Molecular and Genetic Alterations

Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) is characterized by a heterogeneous array of molecular and genetic alterations that disrupt normal hematopoiesis and contribute to disease progression. These changes include both cytogenetic abnormalities and somatic mutations in key genes involved in RNA splicing, epigenetic regulation, and other cellular processes. Approximately 50% of MDS cases harbor chromosomal abnormalities at diagnosis, which often correlate with clinical outcomes.[37] Common chromosomal alterations in MDS include deletions of the long arm of chromosome 5 (del(5q)), monosomy 7 (-7), and complex karyotypes defined as three or more independent abnormalities. Del(5q) occurs in about 10% of cases, frequently as an isolated anomaly or with limited additional changes, and is associated with a distinct subtype featuring macrocytic anemia and thrombocytosis. Monosomy 7 or del(7q) is seen in roughly 10% of patients and is linked to more aggressive disease, often occurring in younger individuals and conferring a higher risk of leukemic transformation. Complex karyotypes, present in 10-15% of MDS cases, are particularly adverse, especially when combined with specific mutations, and are found in up to 91% of high-risk subgroups.[38][39][40] Somatic mutations in splicing factor genes are among the most frequent molecular events in MDS, affecting up to 50% of patients and leading to aberrant RNA processing that impairs hematopoietic differentiation. The SF3B1 gene, mutated in 20-30% of cases, is the most common, with over 90% of these mutations occurring in patients with ring sideroblasts—abnormal erythroid precursors containing iron-laden mitochondria. SF3B1 alterations typically define a lower-risk subtype with indolent progression and favorable survival, though co-occurring mutations can modify this prognosis. Other splicing factors like SRSF2, U2AF1, and ZRSR2 are mutated in 10-15% of cases combined, often associating with multilineage dysplasia.[41][42][43] Mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene occur in 10-20% of MDS patients and are strongly tied to therapy resistance and dismal outcomes, with median survival often under one year in affected cases. These alterations, particularly biallelic or "multi-hit" variants (e.g., high variant allele frequency >50% or combined with loss of the wild-type allele), are enriched in complex karyotypes and predict rapid progression to acute myeloid leukemia. TP53 mutations disrupt DNA repair and apoptosis, rendering cells more vulnerable to genomic instability.[38][44][45] Epigenetic dysregulation plays a central role in MDS pathogenesis through mutations in genes controlling DNA methylation and chromatin modification, affecting up to 50% of cases. TET2 mutations, found in 20-25% of patients, impair DNA demethylation by reducing 5-hydroxymethylcytosine levels, leading to hypermethylation of hematopoietic regulators and clonal expansion. ASXL1 alterations, present in 15-20% of cases, disrupt polycomb repressive complex 2 function, promoting aberrant histone modifications and multilineage involvement with worse survival. DNMT3A mutations, occurring in 10-15% of MDS, cause de novo methyltransferase deficiency, resulting in global hypomethylation that facilitates leukemic evolution, though their prognostic impact varies with co-mutations. These epigenetic changes often arise early, as seen in clonal hematopoiesis, and sensitize cells to hypomethylating agents like azacitidine.[39][46][47] IDH1 and IDH2 mutations, detected in 5-10% of MDS cases, encode isocitrate dehydrogenases that produce the oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate, inhibiting TET enzymes and histone demethylases to induce hypermethylation and block differentiation. IDH2 mutations are more common than IDH1 (roughly 4% vs. 2%), and both are enriched in higher-risk disease with severe neutropenia, associating with inferior survival and potential responsiveness to targeted IDH inhibitors.[48][49][50]Diagnosis

Clinical and Laboratory Evaluation

The clinical evaluation of suspected myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) begins with a detailed medical history to identify persistent cytopenias, recurrent infections, or unexplained bleeding, which often prompt initial assessment.[51][7] A thorough review of prior exposure to chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or other risk factors is essential, as these can contribute to MDS development.[52][53] Physical examination focuses on signs of anemia such as pallor, tachycardia, or fatigue, as well as evidence of thrombocytopenia including easy bruising or petechiae.[51][7] Splenomegaly, if present, is uncommon in MDS and may suggest alternative diagnoses.[52][53] Laboratory evaluation starts with a complete blood count (CBC), which typically reveals persistent cytopenias, including hemoglobin less than 13 g/dL in men or 12 g/dL in women, absolute neutrophil count below 1.8 × 10^9/L, and platelet count under 150 × 10^9/L.[51][7][52][54] These findings, when unexplained by other causes, raise suspicion for MDS.[53] A peripheral blood smear is then examined to detect dysplastic features, such as hypogranular or hyposegmented neutrophils (pseudo-Pelger-Huët anomaly), macro-ovalocytes, or anisopoikilocytosis in red blood cells.[51][7][52] These morphologic abnormalities support the need for further investigation while helping differentiate MDS from nutritional deficiencies or reactive processes.[53] Additional initial laboratory tests include a reticulocyte count, which is often inappropriately low relative to the degree of anemia, indicating ineffective erythropoiesis.[51][7] Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels may be elevated, suggesting increased cell turnover, and measurements of vitamin B12 and folate are performed to exclude deficiencies as alternative causes of cytopenias.[52][53]Bone Marrow Examination

Bone marrow examination is a cornerstone of diagnosing myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), involving both aspiration and biopsy to directly assess marrow cellularity, morphology, and other features in the context of persistent cytopenias observed on peripheral blood evaluation.[54][6] Bone marrow aspiration typically yields 2-3 mL of liquid marrow, which is air-dried and stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa or Wright-Giemsa for morphologic analysis; if aspiration results in a "dry tap," touch preparations from the biopsy core can substitute.[54] The concomitant bone marrow trephine biopsy provides a tissue core for histologic evaluation, complementing the aspirate by revealing architectural details and excluding alternative pathologies such as fibrosis or metastatic disease.[6][55] Assessment of bone marrow cellularity, expressed as the percentage of hematopoietic cells relative to fat and stroma in the biopsy, is routinely performed and often reveals hypercellularity exceeding 30% of the marrow space in MDS cases, though normocellular or hypocellular marrows can occur, particularly in subtypes like hypocellular MDS.[54][6] This evaluation helps contextualize the ineffective hematopoiesis underlying the disease, as hypercellularity contrasts with the peripheral cytopenias.[56] Morphologic evaluation focuses on identifying dysplasia, defined as abnormal maturation and development in hematopoietic cells, requiring at least 10% dysplastic cells in one or more lineages—erythroid, granulocytic, or megakaryocytic—on the aspirate smear for diagnostic significance.[54][6] Dysplastic features may include megaloblastoid changes in erythroids, hypogranulation or pseudo-Pelger-Huët anomalies in granulocytes, or micromegakaryocytes and hypolobated forms in megakaryocytes, with multilineage involvement common in higher-risk MDS.[56] This assessment, performed by counting at least 200-500 cells per lineage, is essential for confirming the dysplastic nature of the marrow.[54] Iron staining, typically using Prussian blue, is applied to the bone marrow aspirate to detect ring sideroblasts, which are erythroid precursors with iron-laden mitochondria forming a ring around at least one-third of the nucleus; their presence is quantified as at least 15% of mature erythroid cells, or 5% in cases associated with specific mutations, indicating subtypes like MDS with ring sideroblasts.[54][6] This finding highlights disordered iron utilization in erythropoiesis and supports subtype delineation when combined with other morphologic data.[56] Flow cytometry on bone marrow samples enhances diagnostic precision by detecting aberrant antigen expression on hematopoietic cells, particularly on CD34-positive blasts and maturing myeloid or erythroid progenitors, which may show abnormal patterns such as underexpression of CD13 or CD33, overexpression of CD56, or dyssynchronous maturation (e.g., altered CD11b/CD16 ratios on neutrophils).[57][54] These immunophenotypic abnormalities, assessed via multiparameter panels including markers like CD45, CD117, HLA-DR, and lineage-specific antigens, occur in over 80% of MDS cases and provide supportive evidence when morphology is equivocal, though they are not entirely specific to MDS.[57] Standardized scoring systems, such as the Ogata or integrated flow cytometry scores, can quantify these aberrancies to aid in risk assessment.[57] Enumeration of blasts in the bone marrow, counted as a percentage of total nucleated cells on the aspirate smear (at least 500 cells), is critical, with levels below 20% supporting an MDS diagnosis and distinguishing it from acute myeloid leukemia, where blasts reach or exceed 20%.[54][6] Increased blasts (5-19%) indicate higher-risk disease, while counts under 5% align with lower-risk categories, guiding further management.[56] Cytogenetic analysis of the bone marrow, including conventional karyotyping (at least 20 metaphases) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for common abnormalities if needed, is essential to identify chromosomal changes such as deletion 5q, monosomy 7, or complex karyotypes, which inform diagnosis, subtype, and prognosis. Molecular genetic testing, typically via targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) panels, detects somatic mutations in recurrently mutated genes including SF3B1, TP53, DNMT3A, ASXL1, and others; these findings are crucial for defining genetically driven MDS subtypes and refining risk assessment per current classifications.[54]Classification Systems

The classification of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) relies on two primary contemporary frameworks: the 5th edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of haematolymphoid tumours (WHO5), published in 2022, and the International Consensus Classification (ICC), also released in 2022.[54][58] These systems integrate morphologic, cytogenetic, and genetic features to define subtypes, aiming to reflect shared pathogenesis and guide clinical management, while resolving ambiguities from prior iterations like the 2016 WHO revision.[59] In the WHO5, MDS is categorized into entities defined by genetics or morphology, with blasts limited to less than 20% in bone marrow or blood to distinguish from acute myeloid leukemia (AML).[54] Genetically defined subtypes include MDS with low blasts and SF3B1 mutation (requiring ≥15% ring sideroblasts or ≥5% if SF3B1-mutated), MDS with low blasts and isolated del(5q), and MDS/acute myeloid leukemia with mutated TP53 (biallelic inactivation, blasts <20%).[54] Morphologic subtypes encompass MDS with low blasts and single lineage dysplasia (SLD, dysplasia ≥10% in one lineage), MDS with low blasts and multilineage dysplasia (MLD, dysplasia ≥10% in ≥2 lineages), and MDS with increased blasts type 1 (IB1, 5-9% bone marrow blasts or 2-4% peripheral blood blasts) or type 2 (IB2, 10-19% bone marrow blasts or 5-19% peripheral blood blasts).[54] Additional categories recognize MDS, hypoplastic (bone marrow cellularity <30-40%, adjusted for age) and MDS with fibrosis (grade 2-3 myelofibrosis).[54] The ICC similarly emphasizes integrated diagnostics but introduces refinements for overlap with AML.[58] Genetically defined types include MDS with mutated SF3B1 (variant allele frequency >10%, blasts <5% in bone marrow and <2% in blood), MDS with del(5q) (isolated or with one other abnormality excluding -7/del(7q), blasts <5%), and MDS with mutated TP53 (multi-hit, variant allele frequency >10%, blasts 0-9% for MDS or 10-19% for MDS/AML).[58] Morphologic categories fall under MDS, not otherwise specified (NOS), with single lineage dysplasia, multilineage dysplasia, or without dysplasia (all blasts <5%), alongside MDS with excess blasts (5-9% bone marrow blasts, 2-5% peripheral blood blasts) and a distinct MDS/AML for cases with 10-19% blasts. Unlike WHO5, ICC does not designate separate hypocellular or fibrotic subtypes as primary entities.[58] Key differences between the systems include WHO5's explicit incorporation of hypocellularity and fibrosis as defining features, reflecting their prognostic relevance, whereas ICC prioritizes genetic drivers and creates an MDS/AML hybrid for intermediate blast counts to better align with AML thresholds.[54] WHO5 also permits SF3B1-mutated MDS with wild-type ring sideroblasts under certain conditions, while ICC mandates the mutation without requiring sideroblasts.[54] Both frameworks eliminate prior ambiguous categories like refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts and unify dysplasia thresholds at ≥10% per lineage, but ICC more aggressively integrates complex karyotypes with TP53 for higher-risk designations.[59][58]| Feature/Subtype | WHO5 (2022) | ICC (2022) |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Defined: SF3B1 | MDS-LB-SF3B1 (≥15% RS or ≥5% if mutated; <5% blasts) | MDS-SF3B1 (>10% VAF; <5% blasts) |

| Genetically Defined: del(5q) | MDS-LB-del(5q) (isolated; <5% blasts) | MDS-del(5q) (isolated or +1 abn.; <5% blasts) |

| Genetically Defined: TP53 | MDS/AML-TP53 (biallelic; <20% blasts) | MDS-TP53 (multi-hit; 0-9% blasts) or MDS/AML-TP53 (10-19% blasts) |

| Morphologic: SLD/MLD | MDS-LB-SLD/MLD (<5% blasts) | MDS-NOS-SLD/MLD (<5% blasts) |

| Excess Blasts | MDS-IB1 (5-9% BM) / IB2 (10-19% BM) | MDS-EB (5-9% BM); MDS/AML (10-19% blasts) |

| Hypocellular | MDS, hypoplastic (<30-40% cellularity) | Not a primary subtype |

| Fibrosis | MDS with fibrosis (grade 2-3) | Not a primary subtype |