Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

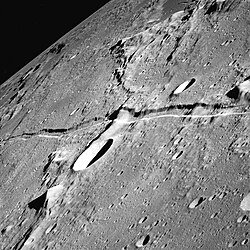

Rille

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

Rille /ˈrɪl/[2] (German for 'groove') is typically used to describe any of the long, narrow depressions in the surface of the Moon that resemble channels. The Latin term is rima, plural rimae. Typically, a rille can be several kilometers wide and hundreds of kilometers in length. However, the term has also been used loosely to describe similar structures on a number of planets in the Solar System, including Mars, Venus, and on a number of moons. All bear a structural resemblance to each other.

Structures

[edit]Three types of rille are found on the lunar surface:

- Sinuous rilles meander in a curved path like a mature river, and are commonly thought to be the remains of collapsed lava tubes or extinct lava flows. They usually begin at an extinct volcano, then meander and sometimes split as they are followed across the surface. As of 2013[update], 195 sinuous rilles have been identified on the Moon.[3] Vallis Schröteri in Oceanus Procellarum is the largest sinuous rille, and Rima Hadley is the only one visited by humans, on the Apollo 15 mission. Another prominent example is Rima Herigonius.

- Arcuate rilles have a smooth curve and are found on the edges of the dark lunar maria. They are believed to have formed when the lava flows that created a mare cooled, contracted and sank. These are found all over the Moon, examples can be seen near the south-western border of Mare Tranquillitatis and on the south-eastern border of Mare Humorum. Rima Sulpicius Gallus is a clear example in southwestern Mare Serenitatis.

- Straight rilles follow long, linear paths and are believed to be grabens, sections of the crust that have sunk between two parallel faults. These can be readily identified when they pass through craters or mountain ranges. Vallis Alpes is by far the largest graben rille, indeed it is regarded as too large to be called a rille and is itself bisected by a linear rille; Rima Ariadaeus, west of Mare Tranquillitatis, is a clearer example.

Rilles which show more than one structure are termed hybrid rilles. Rima Hyginus in Sinus Medii is an example, initially formed through a fault and subsequently subject to volcanic activity.

Formation

[edit]Precise formation mechanisms of rilles have yet to be determined. It is likely that the different types are formed by different processes. Common features shared by lunar rilles and similar structures on other bodies suggest that common causative mechanisms operate widely in the solar system. Leading theories include lava channels, collapsed lava tubes, near-surface dike intrusion, nuée ardente (pyroclastic cloud), subsidence of lava-covered basin and crater floors, and tectonic extension. On-site examination would be necessary to clarify exact methods.

Sinuous rilles

[edit]According to NASA, the origin of lunar sinuous rilles remains controversial.[4] The Hadley Rille is a 1.5 km wide and over 300 m deep sinuous rille. It is thought to be a giant conduit that carried lava from an eruptive vent far to the south. Topographic information obtained from the Apollo 15 photographs supports this possibility; however, many puzzles about the rille remain.[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Selenocromatica". GAWH. Retrieved 19 January 2025.

- ^ "rille". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Hurwitz, D.M.; Head, J.W.; Kring, D.A. (2019). "Atlas of Lunar Sinuous Rilles". Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ a b "ch6.2". History.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2012-09-17.

- General

- Ewen A. Whitaker, Mapping and Naming the Moon, Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-521-62248-4.

- American Astronomers Report: What Formed the Moon's Sinuous Rilles?, Sky & Telescope, Vol. XXVI, No. 1, July, 1963.

- Atlas of Lunar Sinuous Rilles