Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Splitting of the Moon

View on Wikipedia

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Career Views and Perspectives

|

||

| Quran |

|---|

The Splitting of the Moon (Arabic: انشقاق القمر, romanized: Anshiqāq al-Qamar) is a miracle in the Muslim faith attributed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad. The event is referenced in Surah Al-Qamar 54:1–2, where the Moon is said to have split, and is further elaborated in hadith and later Quranic exegesis. Within Islamic belief, many commentators regard it as a literal miracle performed by Muhammad in response to demands from the Meccan polytheists for a supernatural sign, while others interpret the verses as a metaphorical statement.

Origin

[edit]The earliest available tafsir compilations mention the Splitting of the Moon.[1] There is a suggestion that the event would be likely due to a lunar eclipse.[2] The Quran identifies the eclipsed or split Moon as a "sign" (aya, pl. ayat) showcasing the might of Muhammad's God, akin to other natural happenings such as the seed germination and rainfall.[3][4] However, the disbelievers during Muhammad's time referred to this as "enchantment" (sihr), meaning that Muhammad was trying to beguile them into accepting the astronomical event as proof of his prophethood, as they also dismissed as sihr the verbal signs he recited to them, particularly the Quranic warnings about the end of times.[5] Instead, they asked him to provide visual signs that defy the law of nature (miracles), such as causing a fountain to burst forth from the ground, creating a lush garden with flowing rivers amidst palm and grape trees, and building a golden house. Nevertheless, it is opined that Muhammad was able to perform such miraculous signs and thus provided them with various reasons.[6][7][8]

Some are of the opinion that some post-Quranic scholars, aiming at attributing miracles to Muhammad, reinterpreted the verb inshaqqa in the verse from its original figurative meaning to a literal one. As a result, the event of Muhammad interpreting the natural phenomenon of a lunar eclipse in an eschatological context was transformed into an extraordinary miracle of considerable magnitude—the splitting of the Moon.[1][9][10] The narrative was used by some later Muslims to convince others of the prophethood of Muhammad. Annemarie Schimmel for example quotes the following from Muslim scholar Qadi Iyad, who worked in the 12th century:

It has not been said of any people on the earth that the Moon was observed that night such that it could be stated that it was not split. Even if this had been reported from many different places, so that one would have to exclude the possibility that all agreed upon a lie, yet, we would not accept this as proof to the contrary, for the Moon is not seen in the same way by different people... An eclipse is visible in one country but not in the other one; in one place it is total, in the other one only partial.[11]

Other perspectives

[edit]Al-Raghib al-Isfahani, Al-Mawardi and Al-Zamakhshari in their commentaries, in addition to mentioning the miracle, also note that the second half of verse 54:1 can be read as "and the moon will be cleaved", referring to one of the signs of the Islamic end of times.[12]

According to Sebastian R. Prange, during the 12th to 14th centuries CE, the Muslims in Malabar, who were at the time a minority there, composed a story to solidify their community’s influence in the region,[13] claiming that a king of the medieval Chera dynasty called Cheraman Perumal (lit. "Great lord of the Cheras"), or in its Arabic rendering, Shakarwatī Farmad, had witnessed the Moon splitting in his dream. He then partitioned his realm among different lieutenants, journeyed to Arabia to see Muhammad, and died some years later.[14][15] Prange maintains that historical research has found this story to be fictitious.[16]

The Muslim scholar Yusuf Ali provides three different interpretations of the verse. He holds that perhaps all three are applicable to the verse: Moon once appeared cleft asunder at the time of Muhammad to convince the unbelievers. It will split again when the Day of Judgment approaches (here the prophetic past tense is taken to indicate the future). Yusuf Ali connects this incident with the disruption of the Solar System mentioned in 75:8-9. Lastly, he says that the verses can be metaphorical, meaning that the matter has become clear as the Moon.[17]

Some dissenting commentators who do not accept the miracle narration believe that the verse only refers to the splitting of the Moon at the Day of Judgment.[18][19] Likewise, M. A. S. Abdel Haleem writes:

The Arabic uses the past tense, as if that Day were already here, to help the reader/listener imagine how it will be. Some traditional commentators hold the view that this describes an actual event at the time of the Prophet, but it clearly refers to the end of the world.[20]

Historians including A. J. Wensinck and Denis Gril reject the historicity of the miracle, arguing that the Quran itself denies miracles, in the traditional sense, in connection with Muhammad.[21][22]

Debate over the inviolability of heavenly bodies

[edit]Quran 54:1–2 was part of the debate between medieval Muslim theologians and Muslim philosophers over the issue of the inviolability of heavenly bodies. The philosophers held that nature was composed of four fundamental elements: Earth, air, fire, and water. These philosophers however held that the composition of heavenly bodies was different. This belief was based on the observation that the motion of heavenly bodies, unlike that of terrestrial bodies, was circular and without any beginnings or ends. This appearance of eternity in the heavenly bodies led the philosophers to conclude that the heavens were inviolable. Theologians, on the other hand, proposed their own conception of terrestrial matter: Nature was composed of uniform atoms that were re-created at every instant by God (this latter idea was added to defend God's omnipotence against the encroachment of the independent secondary causes). According to this conception, heavenly bodies were essentially the same as terrestrial bodies and thus could be pierced.[23]

To deal with the implications of the traditional understanding of the Quranic verse 54:1–2, some philosophers argued that the verse should be interpreted metaphorically (e.g. the verse could have referred to a partial lunar eclipse, in which then Earth obscured part of the Moon).[23]

Literature

[edit]This tradition has inspired many Muslim poets, especially in India.[21][24] In poetry, Muhammad is sometimes equated with the Sun or the morning light. Sana'i, an early twelfth century Persian Sufi poet, writes: "the Sun should split the Moon in two".[11] In one of his poems, the poet and mystic Jalal ad-Din Rumi expresses that the greatest bliss for the lowly moon is to be split by Muhammad's finger, and a devoted believer splits the moon with Muhammad's finger.[11] In another place, Rumi, according to Schimmel, alludes to two miracles attributed to Muhammad in tradition, i.e. the splitting of the Moon (which shows the futility of man's scientific approach to nature), and the other that Muhammad was illiterate.[11]

Abd ar-Rahman Jami, one of the classical poets and mystics of Persia, plays with the shapes and numerical values of Arabic letters in a complicated way: the full Moon, Jami says, resembles the Arabic letter for M, a circular mīm (ـمـ), with the numerical value 40. When Muhammad split the Moon, its two halves each became like a crescent-shaped nūn (ن) (the Arabic letter for N) whose numerical value is 50 each. This would mean that thanks to the miracle, the value of the Moon had increased.[11]

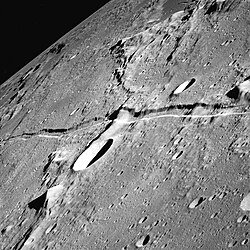

NASA photograph

[edit]

After NASA made an Apollo mission photograph of Rima Ariadaeus available online, it began circulating in the Muslim online community, with "the moon's crack line" being interpreted as evidence that the Moon had once split.[27] NASA clarified that the image shows a lunar rille similar to Earth's geological faults, stretching about 300 km.[28] Astronomer Paul Groot from Radboud University explained that the "split" seen in the photo does not encircle the entire lunar surface, and it possibly relates to the impact that formed the Tycho crater nearby the feature. Additionally, NASA scientist Brad Bailey stated,

No current scientific evidence reports that the Moon was split into two (or more) parts and then reassembled at any point in the past.[27][29]

Therefore, the commonly circulated image is not considered scientific evidence of a literal splitting of the Moon.

See also

[edit]- Islamic view of miracles

- Musa's splitting the sea, for the miracle of splitting the Red Sea, as told in the Quran

- Muhammad in Mecca

- Muhammad's eclipse

References

[edit]- ^ a b Brockopp 2010, p. 47.

- ^ Al-Azmeh 2017, p. 309.

- ^ Brockopp 2010, p. 44.

- ^ Sirry 2021, p. 193–4.

- ^ Brockopp 2010, p. 46.

- ^ Brockopp 2010, p. 45.

- ^ Phipps 2016, p. 40.

- ^ Peters 2010, p. 204.

- ^ Peters 2010, p. 204–5.

- ^ Sirry 2021, p. 193–6.

- ^ a b c d e Schimmel 1985, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Seyyed Hossein Nasr, ed. (2017). "The Moon, al-Qamar". The Study Quran: A New Translation and Commentary.

- ^ Prange 2018, p. 101.

- ^ Prange 2018, p. 93–5.

- ^ (Hurvitz et al. 2020, p. 257)

- ^ Prange 2018, p. 94–5, 100.

- ^ Yusuf Ali, Meaning of The Noble Qur’an, Sura 54, v.1

- ^ Allameh Tabatabaei, Tafsir al-Mizan, Verse 54:1-2

- ^ Majma Ul-Bayan

- ^ M. A. S. Abdel Haleem: The Qur'an, a new translation, note to 54:1

- ^ a b Wensinck, A.J. "Muʿd̲j̲iza". Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C. E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W. P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2007.

- ^ Denis Gril, Miracles, Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, Brill, 2007.

- ^ a b Robert G. Mourison, The Portrayal of Nature in a Medieval Qur’an Commentary, Studia Islamica, 2002

- ^ "Muhammad". Encyclopædia Britannica in Islamic mythology. 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online, p. 13

- ^ "Moon Split Miracle Chain Letter". Hoax Slayer. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020.

- ^ Soora, Gayathri (14 April 2020). "Split Moon image goes viral on WhatsApp; Fact Check | Digit Eye". Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ^ a b "Social media posts falsely claim the Moon 'was once split in two'". AFP Fact Check. 2022-05-04. Archived from the original on 5 August 2023. Retrieved 2023-11-19.

- ^ "Rima Ariadaeus, a Linear Rille". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 March 2010. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

Experts agree that Rima Ariadaeus, about 300 km (186.4 mi) long, is a fault system similar to those on Earth.

- ^ Bailey, Brad (21 June 2010). "Evidence of the moon having been split in two". Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Prange, Sebastian R. (2018-05-03). Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-42438-7.

- Hurvitz, Nimrod; Sahner, Christian C.; Simonsohn, Uriel; Yarbrough, Luke (2020-12-15). Conversion to Islam in the Premodern Age: A Sourcebook. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-29672-5.

- Al-Azmeh, Aziz (2017-02-23). The Emergence of Islam in Late Antiquity: Allah and His People. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-64155-2.

- Brockopp, Jonathan E. (2010-04-19). The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-82838-3.

- Peters, F. E. (2010). Jesus and Muhammad: Parallel Tracks, Parallel Lives. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-978004-4.

- Phipps, William E. (6 October 2016). Muhammad and Jesus: A Comparison of the Prophets and Their Teachings. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4742-8935-1.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1985). And Muhammad Is His Messenger: The Veneration of the Prophet in Islamic Piety. University of North Carolina Press.

- Sirry, Mun'im (2021-06-21). Controversies over Islamic Origins: An Introduction to Traditionalism and Revisionism. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5275-7134-1.