Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rocinha

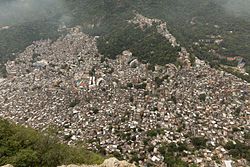

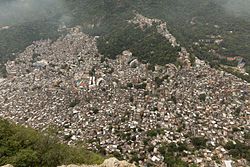

View on WikipediaRocinha (Portuguese pronunciation: [ʁɔˈsĩɲɐ], lit. 'little farm') is a favela, located in Rio de Janeiro's South Zone between the districts of São Conrado and Gávea. Rocinha is built on a steep hillside overlooking Rio de Janeiro, and is located about one kilometre from a nearby beach. Most of the favela is on a very steep hill, with many trees surrounding it. Around 72,000 people live in Rocinha, making it the most populous favela in Rio de Janeiro.[2]

Key Information

Although Rocinha is officially categorized as a neighbourhood, many still refer to it as a favela. It developed from a shanty town into an urbanized slum. Today, almost all the houses in Rocinha are made from concrete and brick. Some buildings are three and four storeys tall and almost all houses have basic plumbing and electricity. Compared to simple shanty towns or slums, Rocinha has a better developed infrastructure and hundreds of businesses such as banks, medicine stores, bus routes, cable television, including locally based channel TV ROC TV Rocinha, and, at one time, a McDonald's franchise.[3] These factors help classify Rocinha as a favela bairro, or favela neighborhood.

History

[edit]In the mid-20th century, Rio de Janeiro's industrial growth attracted many migrants from Brazil's drought-stricken northeast, leading to the formation of informal settlements like Rocinha. Due to a lack of affordable housing, residents built homes themselves, often without proper infrastructure. Rocinha grew rapidly and was recognized as a favela by the 1960s. From the 1970s to 1990s, Rocinha expanded vertically in a crowded and unplanned manner. The government largely neglected the area, leading to the rise of drug cartels and gangs that took control of parts of the community. But with the strong sense of community, the local people established community groups that locally improved town infrastructure and educational facilities and healthcare services.[4]

Community

[edit]

There are a number of community organizations at work in Rocinha, including neighbourhood associations and numerous NGOs and non-profit educational and cultural institutions.[5][6] Rocinha is home to most of the service workers in Zona Sul (the South Zone of Rio).[citation needed]

In recent years, due to its relative safety in comparison to other favelas, Rocinha has developed tourism-oriented activities such as hostels, nightclubs and guided tours. In September 2017, between 150 and 601 tourists were estimated to visit the slum per day, despite foreign governments' and the Rio police's safety warnings recommending against it. In October 2017, a Spanish tourist died after being shot by the police while visiting Rocinha during a turf war.[7]

During the years of 2014 to 2017, Rocinha was controlled by Amigos dos Amigos,[8] and is often caught in violent disputes among (and within) different criminal organizations.[9][7]

Police and military operations

[edit]In November 2011, a security operation was undertaken where hundreds of police and military patrolled the streets of Rocinha to crack down on rampant drug dealers and bring government control to the neighbourhood.[10]

In December 2017, drug kingpin Rogério da Silva, known as Rogério 157, was arrested in Rocinha, in an operation involving 3,000 members of the Brazilian military and police forces. Rogério was wanted on charges of homicide, extortion, and drug trafficking.[11][12]

Rocinha is one of the most developed favelas.[13] Rocinha's population was estimated at between 150,000 and 300,000 inhabitants during the 2000s;[14] but the IBGE Census of 2010 counted only 69,161 people.[15] In 2017, The Economist reported a population of 100,000 in an area of 1 km2 (250 acres).[8]

In literature, film and music

[edit]Robert Neuwirth discusses Rocinha in his book entitled Shadow Cities.[16] Rio de Janeiro was made the setting for the animation film Rio, where many scenes take place in Rocinha.

Also, Rocinha is the setting of the book Nemesis: One Man and the Battle for Rio by Misha Glenny in which he describes the rise and fall of Antônio Francisco Bonfim Lopes.

In 1998, Philip Glass wrote an orchestral piece titled "Days and Nights in Rocinha". It was meant as a reference to Ravel's Boléro, written for Dennis Russell Davies, to thank him for putting Glass' works on stage. He was inspired by dance music that he heard during the carnival, resulting in a samba-like rhythmical structure with a lot of time signature changes and varieties, such as 14/8, 15/8 and 9/8+4/4.

The 2008 film The Incredible Hulk featured aerial footage of Rocinha, showing the large number of intermodal containers repurposed as housing, and included an extensive chase scene filmed in the favela on the ground and across rooftops.[17][better source needed] It was also featured in the 2011 film Fast Five.

In mass media and popular culture

[edit]

Many celebrities have visited Rocinha, including Mikhail Gorbachev (during the Earth Summit of 1992) and actor Christopher Lambert. Some episodes of the Brazilian television series Cidade dos Homens (City of Men) were filmed there.

Video games

[edit]- In the 2009 video game Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2, two of the main campaign missions and a multiplayer map based on it are set in the favela.

- In Call of Duty: Black Ops III, Rocinha is mentioned as the hometown of the specialist Outrider.

- In the 2015 tactical first-person shooter game Tom Clancy's Rainbow Six Siege, a map called "Favela" is based on Rocinha.

- Harran, the city in which Dying Light takes place, was inspired in part by the favela.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2022 Census: 16.4 million persons in Brazil lived in Favelas and Urban Communities | News Agency". Agência de Notícias - IBGE. 8 November 2024. Retrieved 19 September 2025.

- ^ "2022 Census: 16.4 million persons in Brazil lived in Favelas and Urban Communities | News Agency". Agência de Notícias - IBGE. 8 November 2024. Retrieved 19 September 2025.

- ^ Chetwynd, Gareth (2004-04-17). "Deadly setback for a model favela". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2013-08-28. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ acash.org.pk (2025). "The History of Rocinha: Rural Settlement to Urban Favela". acash.org.pk. Retrieved 2025-08-07.

- ^ "Favela Community NGOs Fill the Gaps in Rio's Educational System". RioOnWatch. 17 November 2016. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "Rocinha / Organizações". www.riomaissocial.org (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ a b Kiernan, Paul (28 October 2017). "Rio Police Killing of Spaniard Spotlights Perils of Slum Tourism". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 3 November 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Rio's post-Olympic blues". The Economist. 5 October 2017. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ Glenny, Misha (25 September 2017). "One of Rio de Janeiro's Safest Favelas Descends Into Violence, the Latest Sign of a City in Chaos". The Intercept. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "Brazil police target drug gangs in Rio's biggest slum". BBC News. 13 November 2011. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ Dom Phillips, Rio police hail arrest of drug kingpin in 3,000-strong favela operation Archived 2018-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian (December 6, 2017).

- ^ Dom Phillips & Júlio Carvalho, Arrest of Rio drug kingpin brings fear of power grab – and further violence Archived 2018-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian (December 10, 2017).

- ^ St. Louis, Regis; Draffen, Andrew (2005). Brazil (6 ed.). Lonely Planet. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-74104-021-0. Archived from the original on 2014-06-28. Retrieved 2016-10-16.

- ^ Fodor's Brazil. Random House. 2008. p. 47. ISBN 9781400019663.

- ^ Garcia, Janaina (21 December 2011). "Mais de 11 milhões vivem em favelas no Brasil, diz IBGE; maioria está na região Sudeste". UOL Notícias (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ "Publishers Weekly review - Shadow Cities: A Billion Squatters, a New Urban World". Publishers Weekly. November 2004. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ "Filming locations for The Incredible Hulk". Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ "The Develop Post-Mortem: Dying Light". MCVUK. 1 February 2017. Archived from the original on 27 August 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.