Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

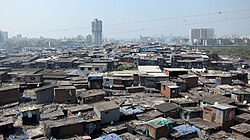

Dharavi

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Dharavi is a residential area in Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. It has often been considered one of the world's largest slums.[1][2] Dharavi has an area of just over 2.39 square kilometres (0.92 sq mi; 590 acres)[3] and a population of about 1,000,000.[4] With a population density of over 418,410/km2 (1,083,677/sq mi), Dharavi is one of the most densely populated areas in the world.

The Dharavi slum was founded in 1884 during the British colonial era, and grew because of the expulsion of factories and residents from the peninsular city centre by the colonial government, and due to the migration of rural Indians into urban Mumbai. For this reason, Dharavi is currently a highly diverse settlement religiously and ethnically.[5]

Dharavi has an active informal economy in which numerous household enterprises employ many of the slum residents[6]—leather, textiles and pottery products are among the goods made inside Dharavi. The total annual turnover has been estimated at over US$1 billion.[7]

Dharavi has suffered from many epidemics and other disasters, including a widespread plague in 1896 which killed over half of the population of Bombay.[8] Sanitation in the slums remains poor.[9]

History

[edit]In the 18th century, Dharavi was an island with a predominantly mangrove swamp.[10] It was a sparsely populated village before the late 19th century, inhabited by Koli fishermen.[11][12] Dharavi was then referred to as the village of Koliwada.[13]

Colonial era

[edit]In the 1850s, after decades of urban growth under East India Company and British Raj, the city's population reached half a million. The urban area then covered mostly the southern extension of Bombay peninsula, the population density was over 10 times higher than London at that time.[13]

The most polluting industries were tanneries, and the first tannery moved from peninsular Bombay into Dharavi in 1887. People who worked with leather, typically a profession of lowest Hindu castes and of Muslim Indians, moved into Dharavi. Other early settlers included the Kumbhars, a large Gujarati community of potters. The colonial government granted them a 99-year land-lease in 1895. Rural migrants looking for jobs poured into Bombay, and its population soared past 1 million. Other artisans, like the embroidery workers from Uttar Pradesh, started the ready-made garments trade.[11] These industries created jobs, labor moved in, but there was no government effort to plan or investment in any infrastructure in or near Dharavi. The living quarters and small scale factories grew haphazardly, without provision for sanitation, drains, safe drinking water, roads or other basic services. But some ethnic, caste and religious communities that settled in Dharavi at that time helped build the settlement of Dharavi by forming organizations and political parties, building school and temples, constructing homes and factories.[12] Dharavi's first mosque, Badi Masjid, started in 1887 and the oldest Hindu temple, Ganesh Mandir, was built in 1883 and organizing Ganesh Chaturthi of 112th year since 1913 folloing the Southern Tirunelveli Culture.[13]

Post-independence

[edit]At India's independence from colonial rule in 1947, Dharavi had grown to be the largest slum in Bombay and all of India. It still had a few empty spaces, which continued to serve as waste-dumping grounds for operators across the city.[13] Bombay, meanwhile, continued to grow as a city. Soon Dharavi was surrounded by the city, and became a key hub for informal economy.[14] Starting from the 1950s, proposals for Dharavi redevelopment plans periodically came out, but most of these plans failed because of lack of financial banking and/or political support.[12] Dharavi's Co-operative Housing Society was formed in the 1960s to uplift the lives of thousands of slum dwellers by the initiative of Shri. M.V. Duraiswamy, a well-known social worker and Congress leader of that region. The society promoted 338 flats and 97 shops and was named as Dr. Baliga Nagar. By the late 20th century, Dharavi occupied about 175 hectares (432 acres), with an astounding population density of more than 2,900 people per hectare (1,200/acre).[13][15]

Redevelopment plan

[edit]The area is a hub for around 5,000 businesses and 15,000 single-room factories across leather, textiles, pottery, metalwork, and recycling, contributing to an annual economic output estimated at over $1 billion (₹10,000 crore). Despite being an economic powerhouse, Dharavi faces significant challenges. A 2006 UNHDR report highlighted an average of one toilet for every 1,440 residents, underscoring the area's inadequate sanitation infrastructure.

There have been many plans since 1997 to redevelop Dharavi like the former slums of Hong Kong such as Tai Hang. In 2004, the cost of redevelopment was estimated to be ₹5,000 crore (US$590 million).[16] The first formal plan for Dharavi’s redevelopment was announced in 2004, but it took the government five years to act on it. When the first tender was finally released in 2009, it saw zero bids which was a sign that developers saw the project as too risky. The tender was cancelled in 2011, and the project stalled once again. Companies from around the world have bid to redevelop Dharavi,[17] including Lehman Brothers, Dubai's Limitless and Singapore's Capitaland Ltd.[17] In 2010, it was estimated to cost ₹15,000 crore (US$1.8 billion) to redevelop.[16]

In 2008 German students Jens Kaercher and Lucas Schwind won a Next Generation prize for their innovative redevelopment strategy designed to protect the current residents from needing to relocate.[18]

Other redevelopment schemes include the "Dharavi Masterplan" devised by British architectural and engineering firm Foster + Partners, that proposes "double-height spaces that create an intricate vertical landscape and reflect the community's way of life" built-in phases that the firm says would "eliminate the need for transit camps," instead catalyzing the rehabilitation of Dharavi "from within."

Sector-Based Approach Fails: 2016

[edit]The next attempt came in 2016, with a different approach which divided Dharavi into five sectors, with MHADA (Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority) handling one, while private developers were invited to bid for the remaining four. Yet, once again, no bidders came forward. Developers feared there was a low return on investment and the challenge of relocating thousands of businesses and families without resistance was a big one.[19]

The Seclink Controversy: 2018 – 2020

[edit]After the unsuccessful bid process and various concessions through the 5 November 2018 Government Resolution, the Dharavi Redevelopment Project/Slum Rehabilitation Authority came out with a tender process in November 2018. Seclink Technology Corporation (STC), a UAE-based firm emerged as the highest bidder with a bid of Rs. 7,200 crore. However, the state government was in talks with Indian Railways to acquire the 45 acres of additional land in Mahim, which posed a major roadblock in the project’s scope. This also led to a legal debate if the government should continue with the existing tender or if a fresh bidding process was required.[20]

In August 2020, the Committee of Secretaries (CoS) finally decided to cancel the 2018 Dharavi redevelopment tender, citing material changes due to the inclusion of 45 acres of railway land. This decision was based on Attorney General Ashutosh Kumbhkoni’s opinion who advised that a fresh tender was the right way to proceed. The Maha Vikas Aghadi (MVA) government, led by Uddhav Thackeray, approved the cancellation on 29 October 2020, and the Housing Department issued a formal resolution on 5 November 2020. Against GoM’s decision, the Highest Bidder (Seclink) filed a writ petition in the High Court, however, the High Court did not issue any stay for the fresh tender process.[21]

A Fresh Start: 2022 – 2023

[edit]In 2022, the newly elected government made significant changes to the tendering process for the fourth time. Taking the learnings from past failures, the Government of Maharashtra issued a global Request for Qualification (RFQ) and Request for Proposal (RFP) with revised terms. This time around, instead of dividing Dharavi into five sectors, the entire redevelopment was consolidated into a single Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV), allowing for integrated planning and execution.[22]

Adani Wins the Bid: 2023

[edit]The fresh bidding process attracted multiple participants, but ultimately, in July 2023, Adani Properties Pvt Ltd sent out a ₹5,069 crore bid and secured the project. In the spring of 2023, it became known that the Indian billionaire Gautam Adani intends to do the reconstruction of Dharavi. Adani Properties Pvt. offers the largest amount of construction investments - 615 million dollars. Mumbai authorities estimate the total cost of the work at $2.4 billion.[23]

This is how Dharavi Redevelopment Project Private Limited (DRPPL) finally started, founded in. As of April 2024, a survey is being conducted by Adani Group to rehabilitate Dharavi residents for redevelopment.[24] On 20 December 2024, the High Court of Bombay awarded the Adani Group after the SecLink Group tried to sue.[25][26]

On 8 March 2025 the Supreme Court refused to stay the redevelopment work by Adani group based on the lawsuit by SecLink Group.[27]

Navbharat Mega Developers Private Limited

[edit]The DRPPL has since been renamed to Navbharat Mega Developers Pvt. Ltd. (NMDPL) is an SPV Company constituted to execute the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP). The Dharavi Redevelopment Project is a first-of-its-kind initiative that aims to transform the Dharavi slum into a state-of-the-art township while preserving its legacy.[28]

NMDPL operates with a strong public-private partnership model: • The Government of Maharashtra holds a 20% stake. • Adani Group holds the remaining 80% and has to bear the responsibility to invest and execute. For the first time in decades, Dharavi’s redevelopment has moved beyond paperwork and politics.[29]

Dharavi’s redevelopment has been nearly two decades in the making pushed now and then due to bureaucratic delays, failed tenders, and concerns over displacement. The land, split between BMC, Indian Railways, and state agencies, saw unplanned settlement growth and demanded immediate course correction. This is when the Government of Maharashtra introduced the Maharashtra Slum Areas (Improvement, Clearance, and Redevelopment) Act of 1971 to rehabilitate the slums rather than displace them. In 1976, the census also attempted to formalize residency through photo passes, but large-scale redevelopment remained elusive.

Demographics

[edit]The total current population of the Dharavi slum is unknown because of fast changes in the population of migrant workers coming from neighbouring Gujarat state, though voter turnout for the 2019 Maharashtra state legislative assembly election was 119,092 (yielding a 60% rate). Some sources suggest it is 300,000[30][31] to about a million.[32] With Dharavi spread over 200 hectares (500 acres), it is also estimated to have a population density of 869,565 people per square mile. Among the people, about 20% work on animal skin production, tanneries and leather goods. Other artisans specialise in pottery work, textile goods manufacturing, retail and trade, distilleries and other caste professions – all of these as small-scale household operations. With a literacy rate of 69%, Dharavi is the most literate slum in India.[33]

The western edge of Dharavi is where its original inhabitants, the Kolis, reside. Dharavi consists of various language speakers such as Gujarati, Hindi, Marathi, Tamil, Telugu, and many more.[34] The slum residents are from all over India, people who migrated from rural regions of many different states.[35]

About 29% of the population of Dharavi is Muslim.[36][37] The Christian population is estimated to be about 6%,[38] while the rest are predominantly Hindus with some Buddhists and other minority religions. The slum has numerous mosques, temples and churches to serve people of Hindu, Islam and Christian faiths, with Badi Masjid, a mosque, as the oldest religious structure in Dharavi.

Location and characteristics

[edit]

Dharavi is a large area situated between Mumbai's two main suburban railway lines, the Western and Central Railways. It is also adjacent to Mumbai Airport. To the west of Dharavi are Mahim and Bandra, and to the north lies the Mithi River. The Mithi River empties into the Arabian Sea through the Mahim Creek. The area of Antop Hill lies to the east while the locality called Matunga is located in the South. Due to its location and poor sewage and drainage systems, Dharavi particularly becomes vulnerable to floods during the wet season.

Dharavi is considered one of the largest slums in the world.[39] The low-rise building style and narrow street structure of the area make Dharavi very cramped and confined. Like most slums, it is overpopulated.

Economy

[edit]

In addition to the traditional pottery and textile industries in Dharavi,[11] there is an increasingly large recycling industry, processing recyclable waste from other parts of Mumbai. Recycling in Dharavi is reported to employ approximately 250,000 people.[40] While recycling is a major industry in the neighborhood, it is also reported to be a source of heavy pollution in the area.[40] The district has an estimated 5,000 businesses[41] and 15,000 single-room factories.[40] Two major suburban railways feed into Dharavi, making it an important commuting station for people in the area going to and from work.

Dharavi exports goods around the world.[6] Often these consist of various leather products, jewellery, various accessories, and textiles. Markets for Dharavi's goods include stores in the United States, Europe, and the Middle East.[6] The total (and largely informal economy) turnover is estimated to be between US$500 million,[7] and US$650 million per year,[42] to over US$1 billion per year.[40] The per capita income of the residents, depending on estimated population range of 300,000 to about 1 million, ranges between US$500 and US$2,000 per year.

A few travel operators offer guided tours through Dharavi, showing the industrial and the residential part of Dharavi and explaining about the problems and challenges Dharavi is facing. These tours give a deeper insight into a slum in general and Dharavi in particular.[43]

Utility services

[edit]Potable water is supplied by the MCGM to Dharavi and the whole of Mumbai. However, a large amount of water is lost due to water thefts, illegal connection and leakage.[44] The community also has a number of water wells that are sources of non-potable water.[citation needed]

Cooking gas is supplied in the form of liquefied petroleum gas cylinders sold by state-owned oil companies,[45] as well as through piped natural gas supplied by Mahanagar Gas Limited.[46]

There are settlement houses that still do not have legal connections to the utility service and thus rely on illegal connection to the water and power supply which means a water and power shortage for the residents in Dharavi.[citation needed]

Sanitation issues

[edit]

Dharavi has severe problems with public health. Water access derives from public standpipes stationed throughout the slum. Additionally, with the limited lavatories they have, they are extremely filthy and broken down to the point of being unsafe. Mahim Creek is a local river that is widely used by local residents for urination and defecation causing the spread of contagious diseases.[11] The open sewers in the city drain to the creek causing a spike in water pollutants, septic conditions, and foul odours. Due to the air pollutants, diseases such as lung cancer, tuberculosis, and asthma are common among residents. There are government proposals in regards to improving Dharavi's sanitation issues. The residents have a section where they wash their clothes in water that people defecate in. This spreads the amount of disease as doctors have to deal with over 4,000 cases of typhoid a day. In a 2006 Human Development Report by the UN, they estimated there was an average of 1 toilet for every 1,440 people.[47]

Epidemics and other disasters

[edit]Dharavi has experienced a long history of epidemics and natural disasters, sometimes with significant loss of lives. The first plague to devastate Dharavi, along with other settlements of Mumbai, happened in 1896, when nearly half of the population died. A series of plagues and other epidemics continued to affect Dharavi, and Mumbai in general, for the next 25 years, with high rates of mortality.[48][49] Dysentery epidemics have been common throughout the years and explained by the high population density of Dharavi. Other reported epidemics include typhoid, cholera, leprosy, amoebiasis and polio.[8][50] For example, in 1986, a cholera epidemic was reported, where most patients were children of Dharavi. Typical patients to arrive in hospitals were in late and critical care condition, and the mortality rates were abnormally high.[51] In recent years, cases of drug resistant tuberculosis have been reported in Dharavi.[52][53]

Fires and other disasters are common. For example, in January 2013, a fire destroyed many slum properties and caused injuries.[54] In 2005, massive floods caused deaths and extensive property damage.[55]

The COVID-19 pandemic also affected the slum. The first case was reported in April 2020.[56]

In the media

[edit]From the main road leading through Dharavi, the place makes a desperate impression. However, once having entered the narrow lanes Dharavi proves that the prejudice of slums as dirty, underdeveloped, and criminal places does not fit real living conditions. Sure, communal sanitation blocks that are mostly in a miserable condition and overcrowded space do not comfort the living. Inside the huts, it is, however, very clean, and some huts share some elements of beauty. Nice curtains at the windows and balconies covered by flowers and plants indicate that people try to arrange their homes as cosy and comfortable as possible.

— Denis Gruber et al. (2005)[57]

In the West, Dharavi was most notably used as the backdrop in the British film Slumdog Millionaire (2008).[58] It has also been depicted in a number of Indian films, including Deewaar (1975), Nayakan (1987), Salaam Bombay! (1988), Parinda (1989), Dharavi (1991), Bombay (1995), Ram Gopal Varma's "Indian Gangster Trilogy" (1998–2005), the Sarkar series (2005–2017), Footpath (2003), Black Friday (2004), Mumbai Xpress (2005), No Smoking (2007), Traffic Signal (2007), Aamir (2008), Mankatha (2011), Thalaivaa (2013), Bhoothnath Returns (2014), Kaala (2018) and Gully Boy (2019).

Dharavi, Slum for Sale (2009) by Lutz Konermann and Rob Appleby is a German documentary.[59] In a programme aired in the United Kingdom in January 2010, Kevin McCloud and Channel 4 aired a two-part series titled Slumming It[60] which centered around Dharavi and its inhabitants. The poem "Blessing" by Imtiaz Dharker is about Dharavi not having enough water. For The Win, by Cory Doctorow, is partially set in Dharavi. In 2014, Belgian researcher Katrien Vankrunkelsven made a 22-minute film on Dharavi which is entitled The Way of Dharavi.[61]

Hitman 2, a video game released in 2018, featured the slums of Mumbai in one of its missions.[62][63] The Mumbai based video game Mumbai Gullies is expected to feature the slums of Dharavi in the fictional map.[64][65][needs update]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Dharavi in Mumbai is no longer Asia's largest slum". The Times of India. 2011. Archived from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ^ Arora, Payal (2019). The Next Billion Users: Digital Life Beyond the West. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 75. ISBN 9780674983786. OCLC 1057240289.

- ^ Ramanathan, Gayatri (6 July 2007). "Shanty-towns emerge targets for development". Livemint. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Grey, Deborah. "India's biggest slum faces wrecking ball as residents fear change". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ Sharma, Kalpana; Rediscovering Dharavi: Story From Asia's Largest Slum (2000) – Penguin Books ISBN 0-14-100023-6

- ^ a b c Ahmed, Zubair (20 October 2008). "Indian slum hit by New York woes". BBC News. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ a b "Jai Ho Dharavi". Nyenrode Business Universiteit. Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ^ a b Swaminathan, M. (1995). "Aspects of urban poverty in Bombay." Environment and Urbanization, 7(1), 133–144

- ^ The Bombay Slum Sanitation Program – Partnering with Slum Communities for SustainableSanitation in a Megalopolis (PDF). Washington: World bank. 1 September 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ D'Cunha, Jose Gerson (1900). "IV The Portuguese Period". The Origins of Bombay (3 ed.). Bombay: Asian Educational Services. p. 265. ISBN 978-81-206-0815-3. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b c d Jacobson, Mark (May 2007). "Dharavi Mumbai's Shadow City". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ a b c Weinstein, Liza (June 2014). Globalization and Community, Volume 23 : Durable Slum : Dharavi and the Right to Stay Put in Globalizing Mumbai. Minneapolis, MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780816683109.

- ^ a b c d e Jan Nijman, A STUDY OF SPACE IN BOMBAY'S SLUMS, Tijdschrift Voor economic en social geographies, Volume 101, Issue 1, pages 4–17, February 2010

- ^ , Eyre, L. (1990), "The shanty towns of central Bombay." Urban Geography 11, pages 130–152

- ^ Graber et al. (2005), "Living and working in slums of Bombay." Working paper 36. Magdeburg: Otto-von-Guericke Universitat, Netherlands

- ^ a b "Calls to scrap Dharavi makeover gain ground". The Times of India. 20 August 2010. Archived from the original on 25 September 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ^ a b Nandy, Madhurima (23 April 2010). "US firm exits Dharavi project citing delays". Livemint. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ info@lafargeholcim-foundation.org, LafargeHolcim Foundation for Sustainable Construction. "Realizing solutions for the redevelopment of Dharavi, Mumbai, In". LafargeHolcim Foundation website. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ "Dharavi redevelopment project: Tender terms turn off developers, no bids". The Indian Express. 21 April 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ Desk, NDTV Profit (20 December 2024). "Dharavi Redevelopment Project: Timeline Of 'Reckless' Seclink Case That Bombay High Court Dismissed". NDTV Profit. Retrieved 7 March 2025.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Plea lacks force, says HC; dismisses SecLink's petition against awarding Dharavi project to Adani". Hindustan Times. 21 December 2024. Archived from the original on 17 January 2025. Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ "Dharavi redevelopment project's special purpose vehicle renamed to avoid confusion with govt authority". The Times of India. 28 December 2024. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ "Миллиардер из Индии решил перестроить район из "Миллионера из трущоб"". RBC (in Russian). 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Mumbai: 2nd Phase Of Dharavi Housing Survey Begins, New Flats To Have Attached Kitchen, Toilets". TimesNow. 2 April 2024. Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ "Bombay HC upholds tender awarded to Adani Group to redevelop Dharavi slum". The Hindu. 20 December 2024. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ "Dharavi slum redevelopment project: Bombay HC dismisses plea against tender awarded to Adani Group". Telegraph India. 20 December 2024. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ "Supreme Court refuses to stay Adani Group's Dharavi redevelopment project". The Indian Express. 8 March 2025. Retrieved 8 March 2025.

- ^ "Dharavi Redevelopment Project Private Ltd (DRPPL) Changes Name To Navbharat Mega Developers Private Ltd (NMDPL)". Free Press Journal. Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ "Dharavi Redevelopment Project renamed to Navbharat Mega Developers". India Today. 29 December 2024. Retrieved 7 March 2025.

- ^ Lewis, Clara (6 July 2011). "Dharavi in Mumbai is no longer Asia's largest slum". The Times of India. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Neelima Risbud (2003). Urban Slums Reports: The case of Mumbai, India, Risbud 2003.

- ^ Yardley, Jim. "Dharavi: Self-created special economic zone for the poor". Deccan Herald. International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ "Mumbai's slums are India's most literate". Dnaindia.com. 27 February 2006. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ^ Fernando, Benita (2 April 2014). "An urbanist's guide to the Mumbai slum of Dharavi". the Guardian. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ Sharma, Kalpana (2000). Rediscovering Dharavi: Stories from Asia's Largest Slum. Penguin Books India; ISBN 978-0141000237

- ^ Dharavi: Mumbai's Shadow City Archived 14 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine National Geographic (2007)

- ^ Census Data: India Archived 15 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine Government of India

- ^ History of Dharavi churches Archived 27 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Dharavi Deanery (2011)

- ^ "Slum areas of Mumbai (Bombay) in India". Kristian Bertel Photography. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d McDougall, Dan (4 March 2007). "Waste not, want not in the £700m slum". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Nandy, Madhurima (23 March 2010). "Harvard students get lessons on Dharavi". Livemint. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Dharavi". BBC News. Archived from the original on 6 September 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ "Mumbai slum tour: why you should see Dharavi". The Times. Archived from the original on 22 May 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Now, a toll-free helpline to check water leakage, theft – Indian Express". Indian Express. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ "Cooking gas cylinders to be sold at petrol pumps". Daily News and Analysis. 24 July 2013. Archived from the original on 15 June 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ^ "Piped gas becomes more attractive for the kitchen". Daily News and Analysis. 14 September 2012. Archived from the original on 15 June 2015.

- ^ Human Development Report 2006 (PDF) (Report). United Nations Development Programme. 2006. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- ^ Gandy, M. (2008), "Landscapes of disaster: water, modernity, and urban fragmentation in Mumbai." Environment and Planning. A, 40(1), 108

- ^ Renapurkar, D. M. (1988). "Distribution and Susceptibility of Xenopsylla astia to DDT in Maharashtra State, India." International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, 9(03), 377–380

- ^ Thomas, Anjali (12 September 2013). "India Restarts Battle Against Leprosy". India Ink. Retrieved 29 July 2024.

- ^ Mehta et al., "An outbreak of cholera in children of Bombay slums," Journal of Diarrhoeal Diseases Research, 4 June(2): page 94

- ^ Udwadia, Z. F., Pinto, L. M., & Uplekar, M. W. (2010). "Tuberculosis management by private practitioners in Mumbai, India: has anything changed in two decades?" PLoS One, 5(8), e12023

- ^ Loewenberg, S. (2012), "India reports cases of totally drug-resistant tuberculosis," The Lancet, 379(9812), 205

- ^ Dharavi turns into fireball as flames engulf slum Archived 25 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine Indian Express (22 January 2013)

- ^ Samaddar, S., Misra, B. A., Chatterjee, R., & Tatano, H. (2012). Understanding Community’s Evacuation Intention Development Process in a Flood Prone Micro-hotspot[permanent dead link], Mumbai. IDRiM Journal, 2(2)

- ^ Joshi, Sahil (1 April 2020). "First coronavirus case reported from Mumbai's Dharavi slum". India Today. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Denis Gruber, Andrea Kirschner, Sandra Mill, Manuela Schach, Steffen Schmekel, and Hardo Seligman, "Living and Working in Slums of Mumbai," Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg, Institut für Soziologie, Magdeburg, Germany, ISSN 1615-8229 (April 2005)

- ^ Mendes, Ana Cristina (2010). "Showcasing India Unshining: Film Tourism in Danny Boyle'sSlumdog Millionaire". Third Text. 24 (4): 471–479. doi:10.1080/09528822.2010.491379. ISSN 0952-8822. S2CID 145021606.

- ^ Dharavi, Slum for Sale at IMDb

- ^ "Slumming It: Dharavi". Channel 4. Archived from the original on 18 January 2010. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ^ Sse Productions bvba (3 April 2015). "Documentary – The Way Of Dharavi 2014". Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Hitman 2: 10 Things To Do In Mumbai That The Game Doesn't Tell You About". TheGamer. 19 July 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ "HITMAN™ 2 - Mumbai on Steam". store.steampowered.com. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ "WHAT IS MUMBAI GULLIES?". GameEon. 27 November 2020. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ January 2021, Bodhisatwa Ray 19 (19 January 2021). "Mumbai Gullies, a GTA styled game from an Indian developer, set to launch soon". TechRadar. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Dharavi: Documenting Informalities. Practical Action June 2018. Jonatan Habib Engqvist and Maria Lantz. ISBN 978-1853397103

Further reading

[edit]- Sharma, Kalpana; "Rediscovering Dharavi: Story From Asia's Largest Slum" (2000) – Penguin Books ISBN 0-14-100023-6

- "Life in a Slum" – BBC News

- Jacobson, Mark (May 2007). "Dharavi Mumbai's Shadow City". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- "Urban poverty in India: A flourishing slum" and "Recycling: A soul-searching business", The Economist, 19 December 2007

- Everyone Wants a Slice of the Dharavi Pie – Live Mint

- Facts About Asia's Largest Slum, Dharavi, Mumbai - TabloidXO

External links

[edit]Dharavi

View on GrokipediaGeography and Location

Physical Layout and Environmental Features

Dharavi occupies approximately 2.1 square kilometers (520 acres) of low-lying reclaimed marshland in central Mumbai, originally comprising mangrove swamps and serving as a sparsely populated fishing village in the 18th century.[8][9] The settlement's layout features a labyrinthine network of narrow lanes, frequently under one meter wide, interspersed with multi-story buildings constructed from corrugated sheets, brick, and recycled materials. These structures house intertwined residential and industrial functions, including leather processing, pottery kilns, and garment workshops clustered in distinct zones such as the Kumbharwada pottery area and the 13th Compound recycling hub.[10][11][12] Environmentally, the area's flat, swamp-derived terrain promotes waterlogging and flooding during monsoons, as heavy rainfall elevates the shallow water table and overflows open sewers integrated into the street layout. Industrial activities discharge effluents into adjacent water bodies like Mahim Creek, exacerbating pollution, while open defecation and unmanaged waste contribute to soil and groundwater contamination.[13][14][15] Water supply is irregular, with many households receiving municipal water for only a few hours daily via communal taps, supplemented by private tankers, heightening vulnerability to microbial contamination and scarcity. Air quality suffers from emissions of unregulated small-scale industries and biomass burning, with studies indicating elevated particulate levels in enclosed workspaces and homes.[16][17][18]Urban Integration and Boundaries

Dharavi spans approximately 520 acres in central Mumbai, positioned strategically between the city's Western and Central railway commuter lines, which form natural boundaries separating it from neighboring formal developments.[19] To the south, it abuts Mahim and the Mahim Creek, while to the north and east, it interfaces with Bandra, Sion, and expanding commercial zones near the Bandra-Kurla Complex.[8] These boundaries, often marked by highways like the Western Express Highway and informal extensions, highlight Dharavi's compact footprint amid Mumbai's heterogeneous urban landscape.[20] The settlement's urban integration stems from its central location, enabling residents and businesses to access Mumbai's broader infrastructure, including nearby stations like Mahim Junction and Bandra, as well as arterial roads such as 90 Feet Road that link it to commercial hubs and the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport.[19] This connectivity supports daily commutes and economic exchanges, with Dharavi's informal pathways and lanes feeding into the city's formal road and rail networks despite inadequate internal provisioning.[21] Economically, Dharavi functions as an embedded component of Mumbai's urban economy, with its clusters of manufacturing—such as leather tanning, pottery, and recycling—directly supplying raw materials and finished goods to formal markets across the city, fostering a symbiotic yet unequal relationship characterized by high productivity amid infrastructural deficits.[22] This integration underscores Dharavi's role as a de facto industrial suburb, where spatial proximity to affluent areas like Bandra-Kurla Complex amplifies its contributions to Mumbai's globalized supply chains, even as boundary demarcations remain contested in ongoing urban planning discourses.[21]Historical Development

Pre-Colonial and Early Colonial Origins

The area now occupied by Dharavi originated as a sparsely populated mangrove swamp and fishing village in pre-colonial India, primarily inhabited by the indigenous Koli community at the northern tip of Parel island, one of the seven islands comprising early Bombay. The Kolis, traditional fisherfolk, established a settlement known as Koliwada, deriving their sustenance from the adjacent Mahim Creek, which served as a vital waterway for fishing and navigation.[23][24] This Koliwada is recorded in historical accounts, such as the Bombay Gazetteers, as one of the six principal Koli settlements in the region, reflecting the community's longstanding presence tied to coastal resources.[23] During the early colonial era, Portuguese control over the Bombay islands from the 16th century introduced limited infrastructure nearby, including a fort and church at Bandra across from Dharavi, but without substantial disruption to the Koli village.[24] After the British East India Company acquired Bombay from Portugal in 1661, initial colonial activities focused on consolidation rather than transformation of peripheral areas like Dharavi; however, early 18th-century swamp reclamation efforts to unify the islands accelerated, causing Mahim Creek to silt up and undermine the Kolis' fishing economy, leading to their gradual displacement.[23][24] In 1737, the British constructed Riwa Fort—also called Kala Qila—in Dharavi as a strategic watchtower to counter threats from Portuguese forces and Maratha expansions, marking one of the earliest permanent colonial structures in the area.[24][23] A survey map by Captain Thomas Dickinson, prepared between 1812 and 1816, illustrates the persisting Koliwada amid rural surroundings, underscoring Dharavi's character as an underdeveloped outpost rather than an urban settlement at the onset of the 19th century.[23]Expansion Under British Rule

Dharavi began forming as a distinct settlement in the marshy lands south of Mahim in the 1880s, during the height of British colonial administration in Bombay, when urban expansion and industrial policies displaced polluting trades from the city center.[7] British municipal authorities, aiming to improve sanitation in the densely packed southern wards, relocated tanneries, potteries, and other odoriferous industries to peripheral swamps like Dharavi, which had previously served as fishing grounds for local Koli communities.[25] This relocation, starting in the mid-19th century amid Bombay's rapid urbanization, attracted migrant artisans barred from central areas due to caste-based occupational restrictions and hygiene regulations enforced under colonial governance.[26] The settlement's expansion accelerated with waves of rural migration driven by economic opportunities in Bombay's burgeoning textile and port sectors, particularly after the establishment of cotton mills in the 1850s, which swelled the city's population to approximately 500,000 by that decade.[7] Famines in the Deccan regions, such as the widespread scarcity of 1876–1878, pushed laborers from Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Tamil Nadu toward the city, where Dharavi offered affordable, unregulated space for informal housing and workshops.[26] Potters from Saurashtra and Muslim leather tanners from southern India formed early enclaves, establishing Kumbharwada as a pottery hub by relocating kilns from overcrowded urban fringes, while the absence of formal planning allowed haphazard growth across the swampy terrain.[24] [25] By the late 19th century, Dharavi had evolved into a sprawling informal economy hub, incorporating diverse trades like embroidery and recycling, sustained by the colonial economy's demand for cheap labor but unchecked by infrastructure investments that prioritized the European-dominated Fort area.[26] The 1896–1897 bubonic plague epidemic prompted British clearances in central Bombay, further funneling displaced residents and small-scale manufacturers into Dharavi, where lax enforcement of building codes enabled vertical expansion and densification without municipal oversight.[7] This pattern reflected broader colonial priorities favoring commercial zones over proletarian housing, resulting in Dharavi's transformation from isolated potter and tanner colonies into a consolidated shanty network by the early 20th century.[24]Post-Independence Evolution to 2000

Following India's independence in 1947, Dharavi experienced accelerated expansion driven by sustained rural-to-urban migration, as economic opportunities in Bombay's textile mills, docks, and emerging industries attracted laborers from across the country, particularly from Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar.[27] Although already the largest slum in the city by that time, its footprint grew on former swampland and marshy areas, with informal settlements densifying around key sectors like leather tanning, which diversified into pottery, garment manufacturing, and small-scale recycling to accommodate the influx.[27] This organic growth reflected broader Mumbai trends, where the squatter population surged post-1947, eventually comprising about 63% of the city's residents by the early 2000s, occupying just 8% of land at extreme densities exceeding 18,000 persons per square kilometer.[19] In the 1950s and 1960s, municipal and state authorities pursued slum clearance under acts like the Bombay Slum Clearance Act of 1956, aiming to demolish hutments and relocate residents to subsidized housing on the city's periphery; however, these efforts largely failed in Dharavi, as evicted dwellers quickly reoccupied sites due to proximity to employment hubs and the impracticality of distant relocations amid ongoing migration.[28][29] By the 1961 census, Mumbai's slum population stood at around 12% of the total urban populace, with Dharavi—spanning approximately 330 acres—solidifying as the preeminent informal settlement, its persistence underscoring the limitations of clearance-focused policies that ignored economic embeddedness and land scarcity. The 1970s marked a policy pivot toward in-situ improvement, exemplified by the national Slum Improvement Programme, which introduced basic amenities like water taps, community latrines, roads, drainage, and street lighting to Dharavi and similar areas, though coverage remained uneven due to funding constraints and rapid densification.[29] In 1971, the Maharashtra Slum Areas (Improvement, Clearance and Redevelopment) Act formally recognized Dharavi as a slum area, granting eligible residents provisional tenure rights and facilitating incremental upgrades rather than wholesale eviction, which stabilized some tenancies while enabling further industrial clustering in pottery and textiles.[23][30] By the 1980s and 1990s, approaches evolved to incorporate market mechanisms, with pilot projects testing cross-subsidized redevelopment where private developers built replacement housing in exchange for saleable floor space on upper floors; yet, in Dharavi, implementation lagged owing to land title disputes, resident resistance to relocation, and the area's entrenched informal economy.[29] The establishment of the Slum Rehabilitation Authority in 1995 under the Shiv Sena-BJP administration introduced a structured scheme with incentives for developers, setting a January 1, 1995, cut-off for eligibility to curb post-policy encroachments, though actual rehousing in Dharavi remained minimal by 2000, preserving its status as a dense, self-sustaining enclave amid Mumbai's metropolitan boom.[19][29]Redevelopment Efforts from 2000 to 2025

In 2004, the Maharashtra state government approved the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP), appointing the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) to oversee the transformation of the informal settlement into planned housing and infrastructure, with an initial focus on rehabilitating eligible residents through public-private partnerships.[31][32] Early efforts included surveys conducted between 2007 and 2008 to identify pre-2000 residents eligible for free rehabilitation housing, typically 350 square feet per family, while developers would fund the project by selling a portion of the redeveloped land commercially.[31][33] The project faced repeated delays through the 2010s due to legal challenges, tender disputes, and allegations of irregularities in the bidding process, including a 2010 scandal involving the previous tender winner, which led to its cancellation.[32] In 2018, the state issued a new tender for a seven-year redevelopment timeline under a model allocating 20% of land for government use and 80% for private development to cross-subsidize rehabilitation costs.[26] Dubai-based Emaar Properties initially secured the bid but faced court challenges from competitors, stalling progress until 2022, when the Adani Group's consortium, Navbharat Mega Developers Private Limited, emerged as the winning bidder with a commitment to invest over ₹20,000 crore in rehabilitation alone.[26][32] From 2022 onward, implementation accelerated under the Adani-led plan, valued at approximately ₹3 lakh crore overall, with rehabilitation targeted for completion in seven years and full development spanning up to 17 years by 2032 or later.[34][35] Key milestones included ongoing resident surveys to verify eligibility—limited to those settled before January 1, 2000—and the release of the first eligibility list on July 2, 2025, covering thousands of households.[33][36] The master plan, incorporating upgraded infrastructure, commercial spaces, and skill-training centers, was nearing final approval by mid-2025, though post-2000 migrants—estimated to comprise a significant portion of the population—faced relocation risks without guaranteed in-situ housing.[36][37] Controversies persisted, with opposition parties, including Congress leaders like Prithviraj Chavan and Varsha Gaikwad, labeling the project a "scam" involving undervalued land allocation to Adani and potential displacement of ineligible residents, claims the state government dismissed as politically motivated ahead of the 2024 Maharashtra elections.[38][39] Resident groups expressed concerns over transparency in surveys and the adequacy of 350-square-foot units for preserving small-scale industries, while the ruling Mahayuti alliance's 2024 election victory facilitated renewed momentum, including land reallocations like the transfer of 43% of project land for free sale to offset costs.[40][41][42] Adani executives described the initiative as their "most transformative" endeavor, emphasizing social impact through infrastructure like roads, water supply, and economic hubs, though independent verification of long-term viability remains pending as construction phases commence.[43][44]Demographics

Population Estimates and Density

Estimates of Dharavi's population vary due to the absence of formal census data in this informal settlement, with figures commonly ranging from 700,000 to over 1 million as of 2025.[45] Recent reports tied to redevelopment planning assess the current population at nearly 1 million residents.[46] [47] The area encompasses approximately 2.39 square kilometers.[48] Alternative measurements cite 2.1 square kilometers.[49] Population density, derived from these estimates, reaches over 400,000 persons per square kilometer when using the higher population figure and larger area, marking it among the world's most densely populated urban zones.[48] A 2021 analysis reported a density of 340,000 per square kilometer based on an 850,000 population in 2.16 square kilometers.[11] Redevelopment projections anticipate reducing the population to around 485,000, thereby lowering density significantly.[46]Socioeconomic and Migration Profiles

Dharavi's residents face low socioeconomic standing, characterized by limited access to formal employment and basic amenities, with most households reporting monthly incomes below 5,000 Indian rupees (approximately 60 USD), far undercutting Mumbai's citywide average exceeding 20,000 rupees.[50] Per capita annual income estimates range from 500 to 2,000 USD, reflecting reliance on informal labor in small-scale industries where unskilled workers earn around 12,500 rupees monthly and skilled ones up to 30,000 rupees.[51][52] A majority of the working-age population—predominantly aged 18-45—participates in the informal economy, with employment dynamics varying by sector but often involving long hours in household-based enterprises that yield variable and low wages.[53] Migration drives Dharavi's demographic composition, with residents primarily consisting of internal migrants from rural India seeking urban job prospects amid limited opportunities in home regions.[54] Key origins include Uttar Pradesh for garment and embroidery trades, Tamil Nadu for leather tanning and pottery, Bihar and Bengal for general labor, and Gujarat for pottery, alongside smaller inflows from Nepal.[19][55][34] This pattern aligns with Mumbai's broader influx, where 1971 census data showed 57% of the population born outside the city, fueling slum growth through chains of kinship and skill-based networks rather than random settlement.[54] Recent increases in migrants from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar have sustained population density despite redevelopment pressures.[56]Ethnic, Religious, and Linguistic Diversity

Dharavi's ethnic composition reflects India's internal migration patterns, with residents primarily from southern, western, and northern states, including significant Tamil communities engaged in pottery and tanning, Gujarati potters, and Uttar Pradesh migrants in embroidery and garment work.[19][57] A 2009 survey indicated Tamils comprising about 55% of the population, Marathi speakers around 20%, and Gujaratis a notable minority, though these proportions may have shifted with ongoing migration.[57] The area hosts diverse castes, with a substantial proportion of Scheduled Castes and other backward classes, including many Dalits who faced exclusion in rural areas.[58][59] Religiously, Dharavi exhibits pluralism, with Hindus forming the majority at approximately 60-63%, Muslims around 30-33%, Christians about 6-9%, and smaller Buddhist and other groups.[60][55][3] These estimates derive from local surveys and redevelopment studies, though exact figures vary due to informal settlement challenges in census enumeration; historical data from the 1990s suggested higher Muslim proportions near 40% amid communal tensions.[61] Coexistence occurs amid shared economic spaces, with temples, mosques, and churches integrated into neighborhoods.[59] Linguistically, over 30 languages are spoken, underscoring the settlement's role as a pan-Indian melting pot, with Tamil, Marathi, Hindi, and Gujarati predominant alongside regional dialects from migrants' origins.[62] Multilingualism facilitates trade but also reinforces ethnic enclaves within sub-areas like Kumbharwada (potters) or Muslim-dominated tanning zones.[63][64] This diversity stems from post-independence rural-to-urban flows, enabling cultural festivals and hybrid practices across groups.[65]Economic Dynamics

Key Industries in the Informal Sector

Dharavi's informal sector features a proliferation of small-scale, household-based enterprises focused on manufacturing and processing, including recycling, leather goods, textiles, and pottery, often operating in single-room factories estimated at 15,000 units.[53] These activities leverage low-cost labor and proximity to raw materials, fostering interlinked supply chains where waste from one industry fuels another, such as leather scraps used to power pottery kilns.[66] Self-employment in tailoring, textiles, and related trades accounts for a significant portion of local livelihoods, with surveys indicating 48% of residents engaged in such independent work.[53] Recycling stands out as a dominant industry, with operations processing around 60% of Mumbai's plastic waste through manual sorting, shredding, and resale to formal manufacturers, employing 10,000 to 12,000 workers in collection and processing roles.[67][68] This sector handles diverse materials like plastics, metals, and paper, contributing to Mumbai's overall waste management by diverting landfill-bound refuse into reusable commodities.[5] Leather processing, including tanning and crafting of bags, shoes, and apparel, occupies dedicated areas and supports export markets, with businesses enduring challenges like fires while maintaining operations in cramped workshops.[69] These units rely on imported hides and local dyeing, integrating with global fashion supply chains despite regulatory hurdles on pollution.[51] Textile production encompasses dyeing, printing, embroidery, and garment assembly, with thousands of workers producing items for domestic retail and international brands in informal clusters that emphasize speed and customization.[70] Pottery manufacturing, centered in Kumbharwada, involves artisan communities shaping clay into utilitarian and decorative items using traditional wheel-throwing and kiln-firing methods, sustained by intergenerational skills.[53] These industries collectively underscore Dharavi's role as a hub of adaptive, resource-efficient production amid urban constraints.[71]