Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

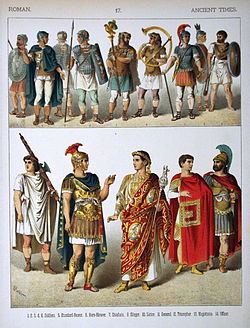

Ancient Roman military clothing

View on Wikipedia

The legions of the Roman Republic and Empire had a fairly standardised dress and armour, particularly from approximately the early to mid 1st century onward, when Lorica Segmentata (segmented armour) was introduced.[1] However the lack of unified production for the Roman army meant that there were still considerable differences in detail. Even the armour produced in state factories varied according to the province of origin.[2]

The other problem is that the Romans took or stole most of the designs from other peoples. Fragments of surviving clothing and wall paintings indicate that the basic tunic of the Roman soldier was of red or undyed (off-white) wool.[3] Senior commanders are known to have worn white cloaks and plumes. The centurions, who made up the officer ranks, had decorations on their chest plates corresponding to modern medals, and the long cudgels that they carried.

Examples of items of Roman military personal armour included:

- Galea or soldier's helmet. Variant forms included the Coolus helmet, Montefortino helmet, and Imperial helmet.

- Greaves, to protect the legs.

- Lorica (armour), including:

- Lorica hamata (mail armour)

- Lorica manica (arm guards)

- Lorica plumata (a form of scale armour resembling feathers)

- Lorica segmentata (segmented armour)

- Lorica squamata (scale armour)

- Lorica musculata (muscle armour)

- Pteruges, perhaps mostly for senior ranks, formed a defensive skirt of leather or multi-layered fabric (linen) strips or lappets worn dependant from the waists of cuirasses

Other garments and equipment included:

- A tunic

- The baldric, a belt worn over one shoulder that is typically used to carry a weapon (usually a sword) or other implement such as a bugle or drum

- The balteus, the standard belt worn by the Roman legionary. It was probably used to tuck clothing into or to hold weapons.

- Braccae (trousers), popular among Roman legionaries stationed in cooler climates to the north of southern Italy

- Caligae, heavy-soled military shoes or sandals which were worn by Roman legionary soldiers and auxiliaries throughout the history of the Roman Republic and Empire.

- The focale, a scarf worn by the Roman legionary to protect the neck from chafing caused by constant contact with the soldier's armor

- The loculus, a satchel, carried by legionaries as a part of their sarcina (marching pack)

- The paludamentum, a cloak or cape fastened at one shoulder, worn by military commanders and (less often) by their troops. Ordinary soldiers wore a sagum instead of a paludamentum.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Michael Simkins, page 17 "The Roman Army from Hadrian to Constantine", Osprey Publishing 1979"

- ^ Windrow, Martin (1996). Imperial Rome at War. p. 16. ISBN 962-361-608-2.

- ^ Sumner, Graham (2009). Roman Military Dress. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-07524-4576-2.

External links

[edit]- Beginners' Guide to Roman Military Equipment at museums.ncl.ac.uk

- Graham Sumner's website

.JPG/250px-Ancient_Times,_Roman._-_017_-_Costumes_of_All_Nations_(1882).JPG)

.JPG/1523px-Ancient_Times,_Roman._-_017_-_Costumes_of_All_Nations_(1882).JPG)