Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Serial Peripheral Interface

View on WikipediaThis article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as it reads like a guide or textbook. (March 2021) |

| Type | Serial communication bus | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Production history | |||

| Designer | Motorola | ||

| Designed | Around early 1980s[note 1] | ||

| Manufacturer | Various | ||

| Daisy chain | Depends on devices | ||

| Connector | Unspecified | ||

| Electrical | |||

| Max. voltage | Unspecified | ||

| Max. current | Unspecified | ||

| Data | |||

| Width | 1 bit (bidirectional) | ||

| Max. devices | Multidrop limited by slave selects. Daisy chaining unlimited. | ||

| Protocol | Full-duplex serial | ||

| Pinout | |||

| MOSI | Master Out Slave In | ||

| MISO | Master In Slave Out | ||

| SCLK | Serial Clock | ||

| SS | Slave Select (one or more) | ||

| (pins may have alternative names) | |||

Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) is a de facto standard (with many variants) for synchronous serial communication, used primarily in embedded systems for short-distance wired communication between integrated circuits.

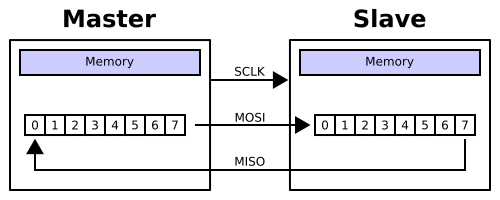

SPI follows a master–slave architecture,[1] where a master device orchestrates communication with one or more slave devices by driving the clock and chip select signals. Some devices support changing master and slave roles on the fly.

Motorola's original specification (from the early 1980s) uses four logic signals, aka lines or wires, to support full duplex communication. It is sometimes called a four-wire serial bus to contrast with three-wire variants which are half duplex, and with the two-wire I²C and 1-Wire serial buses.

Typical applications include interfacing microcontrollers with peripheral chips for Secure Digital cards, liquid crystal displays, analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog converters, flash and EEPROM memory, and various communication chips.

Although SPI is a synchronous serial interface,[2] it is different from Synchronous Serial Interface (SSI). SSI employs differential signaling and provides only a single simplex communication channel.

Operation

[edit]

Commonly, SPI has four logic signals. Variations may use different names or have different signals.

Abbr. Name Description SSSlave SelectActive-low chip select signal from master to

enable communication with a specific slave deviceSCLKSerial ClockClock signal from master MOSIMaster Out Slave InSerial data output from master MISOMaster In Slave OutSerial data output from slave

MOSI on a master outputs to MOSI on a slave. MISO on a slave outputs to MISO on a master.

Each device internally uses a shift register for serial communication, which together forms an inter-chip circular buffer.

Slave devices should use tri-state outputs so their MISO signal becomes high impedance (electrically disconnected) when the device is not selected. Slaves without tri-state outputs cannot share a MISO line with other slaves without using an external tri-state buffer.

Data transmission

[edit]

To begin communication, the SPI master first selects a slave device by pulling its SS low. (The bar above SS indicates it is an active low signal, so a low voltage means "selected", while a high voltage means "not selected")

If a waiting period is required, such as for an analog-to-digital conversion, the master must wait for at least that period of time before issuing clock cycles.[note 2]

During each SPI clock cycle, full-duplex transmission of a single bit occurs. The master sends a bit on the MOSI line while the slave sends a bit on the MISO line, and then each reads their corresponding incoming bit. This sequence is maintained even when only one-directional data transfer is intended.

Transmission using a single slave involves one shift register in the master and one shift register in the slave, both of some given word size (e.g. 8 bits). The transmissions often consist of eight-bit words, but other word-sizes are also common, for example, sixteen-bit words for touch-screen controllers or audio codecs, such as the TSC2101 by Texas Instruments, or twelve-bit words for many digital-to-analog or analog-to-digital converters.

Data is usually shifted out with the most-significant bit (MSB) first but the original specification has a LSBFE ("LSB-First Enable") to control whether data is transferred least (LSB) or most significant bit (MSB) first. On the clock edge, both master and slave shift out a bit to its counterpart. On the next clock edge, each receiver samples the transmitted bit and stores it in the shift register as the new least-significant bit. After all bits have been shifted out and in, the master and slave have exchanged register values. If more data needs to be exchanged, the shift registers are reloaded and the process repeats. Transmission may continue for any number of clock cycles. When complete, the master stops toggling the clock signal, and typically deselects the slave.

If a single slave device is used, its SS pin may be fixed to logic low if the slave permits it. With multiple slave devices, a multidrop configuration requires an independent SS signal from the master for each slave device, while a daisy-chain configuration only requires one SS signal.

Every slave on the bus that has not been selected should disregard the input clock and MOSI signals. And to prevent contention on MISO, non-selected slaves must use tristate output. Slaves that are not already tristate will need external tristate buffers to ensure this.[3]

Clock polarity and phase

[edit]In addition to setting the clock frequency, the master must also configure the clock polarity and phase with respect to the data. Motorola[4][5] named these two options as CPOL and CPHA (for clock polarity and clock phase) respectively, a convention most vendors have also adopted.

The SPI timing diagram shown is further described below:

- CPOL represents the polarity of the clock. Polarities can be converted with a simple inverter.

- SCLKCPOL=0 is a clock which idles at the logical low voltage.

- SCLKCPOL=1 is a clock which idles at the logical high voltage.

- CPHA represents the phase of each data bit's transmission cycle relative to SCLK.

- For CPHA=0:

- The first data bit is output immediately when SS activates.

- Subsequent bits are output when SCLK transitions to its idle voltage level.

- Sampling occurs when SCLK transitions from its idle voltage level.

- For CPHA=1:

- The first data bit is output on SCLK's first clock edge after SS activates.

- Subsequent bits are output when SCLK transitions from its idle voltage level.

- Sampling occurs when SCLK transitions to its idle voltage level.

- Conversion between these two phases is non-trivial.

- MOSI and MISO signals are usually stable (at their reception points) for the half cycle until the next bit's transmission cycle starts, so SPI master and slave devices may sample data at different points in that half cycle, for flexibility, despite the original specification.

- For CPHA=0:

Mode numbers

[edit]The combinations of polarity and phases are referred to by these "SPI mode" numbers with CPOL as the high order bit and CPHA as the low order bit:

| SPI mode | Clock polarity (CPOL) |

Clock phase (CPHA) |

Data is shifted out on | Data is sampled on |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | falling SCLK, and when SS activates | rising SCLK |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | rising SCLK | falling SCLK |

| 2 | 1 | 0 | rising SCLK, and when SS activates | falling SCLK |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | falling SCLK | rising SCLK |

Notes:

- Another commonly used notation represents the mode as a (CPOL, CPHA) tuple; e.g., the value '(0, 1)' would indicate CPOL=0 and CPHA=1.

- In Full Duplex operation, the master device could transmit and receive with different modes. For instance, it could transmit in Mode 0 and be receiving in Mode 1 at the same time.

- Different vendors may use different naming schemes, like CKE for clock edge or NCPHA for the inversion of CPHA.

Valid communications

[edit]Some slave devices are designed to ignore any SPI communications in which the number of clock pulses is greater than specified. Others do not care, ignoring extra inputs and continuing to shift the same output bit. It is common for different devices to use SPI communications with different lengths, as, for example, when SPI is used to access an IC's scan chain by issuing a command word of one size (perhaps 32 bits) and then getting a response of a different size (perhaps 153 bits, one for each pin in that scan chain).

Interrupts

[edit]Interrupts are outside the scope of SPI; their usage is neither forbidden nor specified, and so may be implemented optionally.

From master to slave

[edit]Microcontrollers configured as slave devices may have hardware support for generating interrupt signals to themselves when data words are received or overflow occurs in a receive FIFO buffer,[6] and may also set up an interrupt routine when their slave select input line is pulled low or high.

From slave to master

[edit]SPI slaves sometimes use an out-of-band signal (another wire) to send an interrupt signal to a master. Examples include pen-down interrupts from touchscreen sensors, thermal limit alerts from temperature sensors, alarms issued by real-time clock chips, SDIO[note 3] and audio jack insertions for an audio codec. Interrupts to master may also be faked by using polling (similarly to USB 1.1 and 2.0).

Software design

[edit]SPI lends itself to a "bus driver" software design. Software for attached devices is written to call a "bus driver" that handles the actual low-level SPI hardware. This permits the driver code for attached devices to port easily to other hardware or a bit-banging software implementation.

Bit-banging the protocol

[edit]The pseudocode below outlines a software implementation ("bit-banging") of SPI's protocol as a master with simultaneous output and input. This pseudocode is for CPHA=0 and CPOL=0, thus SCLK is pulled low before SS is activated and bits are inputted on SCLK's rising edge while bits are outputted on SCLK's falling edge.

- Initialize SCLK as low and SS as high

- Pull SS low to select the slave

- Loop for however many number of bytes to transfer:[note 4]

- Initialize

byte_outwith the next output byte to transmit - Loop 8 times:

- Left-Shift[note 5] the next output bit from

byte_outto MOSI - NOP for the slave's setup time

- Pull SCLK high

- Left-Shift the next input bit from MISO into

byte_in - NOP for the slave's hold time

- Pull SCLK low

- Left-Shift[note 5] the next output bit from

byte_innow contains that recently-received byte and can be used as desired

- Initialize

- Pull SS high to unselect the slave

Bit-banging a slave's protocol is similar but different from above. An implementation might involve busy waiting for SS to fall or triggering an interrupt routine when SS falls, and then shifting in and out bits when the received SCLK changes appropriately for however long the transfer size is.

Bus topologies

[edit]Though the previous operation section focused on a basic interface with a single slave, SPI can instead communicate with multiple slaves using multidrop, daisy chain, or expander configurations.

Multidrop configuration

[edit]

In the multidrop bus configuration, each slave has its own SS, and the master selects only one at a time. MISO, SCLK, and MOSI are each shared by all devices. This is the way SPI is normally used.

Since the MISO pins of the slaves are connected together, they are required to be tri-state pins (high, low or high-impedance), where the high-impedance output must be applied when the slave is not selected. Slave devices not supporting tri-state may be used in multidrop configuration by adding a tri-state buffer chip controlled by its SS signal.[3] (Since only a single signal line needs to be tristated per slave, one typical standard logic chip that contains four tristate buffers with independent gate inputs can be used to interface up to four slave devices to an SPI bus)

Caveat: All SS signals should start high (to indicate no slaves are selected) before sending initialization messages to any slave, so other uninitialized slaves ignore messages not addressed to them. This is a concern if the master uses general-purpose input/output (GPIO) pins (which may default to an undefined state) for SS and if the master uses separate software libraries to initialize each device. One solution is to configure all GPIOs used for SS to output a high voltage for all slaves before running initialization code from any of those software libraries. Another solution is to add a pull-up resistor on each SS, to ensure that all SS signals are initially high.[3]

Daisy chain configuration

[edit]

Some products that implement SPI may be connected in a daisy chain configuration, where the first slave's output is connected to the second slave's input, and so on with subsequent slaves, until the final slave, whose output is connected back to the master's input. This effectively merges the individual communication shift registers of each slave to form a single larger combined shift register that shifts data through the chain. This configuration only requires a single SS line from the master, rather than a separate SS line for each slave.[7]

In addition to using SPI-specific slaves, daisy-chained SPI can include discrete shift registers for more pins of inputs (e.g. using the parallel-in serial-out 74xx165)[8] or outputs (e.g. using the serial-in parallel-out 74xx595)[9] chained indefinitely. Other applications that can potentially interoperate with daisy-chained SPI include SGPIO, JTAG,[10] and I2C.

Expander configurations

[edit]Expander configurations use SPI-controlled addressing units (e.g. binary decoders, demultiplexers, or shift registers) to add chip selects.

For example, one SS can be used for transmitting to a SPI-controlled demultiplexer an index number controlling its select signals, while another SS is routed through that demultiplexer according to that index to select the desired slave.[11]

Pros and cons

[edit]Advantages

[edit]- Full duplex communication in the default version of this protocol

- Push-pull drivers (as opposed to open drain) provide relatively good signal integrity and high speed

- Higher throughput than I²C or SMBus

- SPI's protocol has no maximum clock speed, however:

- Individual devices specify acceptable clock frequencies

- Wiring and electronics limit frequency

- SPI's protocol has no maximum clock speed, however:

- Complete protocol flexibility for the bits transferred

- Not limited to 8-bit symbols

- Arbitrary choice of message size, content, and purpose

- Simple hardware and interfacing

- Hardware implementation for slaves only requires a selectable shift register

- Uses only four pins on IC packages, and wires in board layouts or connectors, much fewer than parallel interfaces

- At most one unique signal per device (SS); all others are shared

- The daisy-chain configuration does not need more than one shared SS

- At most one unique signal per device (SS); all others are shared

- Typically lower power requirements than I²C or SMBus due to less circuitry (including pull up resistors)

- Single master means no bus arbitration (and associated failure modes) - unlike CAN-bus

- Transceivers are not needed - unlike CAN-bus

- Signals are unidirectional, allowing for easy galvanic isolation

Disadvantages

[edit]- Requires more pins on IC packages than I²C, even in three-wire variants

- Only handles short distances compared to RS-232, RS-485, or CAN-bus (though distance can be extended with the use of transceivers like RS-422)

- Extensibility severely reduced when multiple slaves using different SPI Modes are required

- Access is slowed down when master frequently needs to reinitialize in different modes

- No formal standard

- So validating conformance is not possible

- Many existing variations complicate support

- No built-in protocol support for some conveniences:

- No hardware flow control by the slave (but the master can delay the next clock edge to slow the transfer rate)

- No hardware slave acknowledgment (the master could be transmitting to nowhere and not know it)

- No error-checking protocol

- No hot swapping (dynamically adding nodes)

- Interrupts are outside the scope of SPI (see § Interrupts)

Applications

[edit]SPI is used to talk to a variety of peripherals, such as

- Sensors: temperature, pressure, ADC, touchscreens, video game controllers

- Control devices: audio codecs, digital potentiometers, DACs

- Camera lenses: Canon EF lens mount

- Memory: flash and EEPROMs

- Real-time clocks

- LCDs, sometimes even for managing image data

- Any MMC or SD card (including SDIO variant[note 3])

- Shift registers for additional I/O[8][9]

Board real estate and wiring savings compared to a parallel bus are significant, and have earned SPI a solid role in embedded systems. That is true for most system-on-a-chip processors, both with higher-end 32-bit processors such as those using ARM, MIPS, or PowerPC and with lower-end microcontrollers such as the AVR, PIC, and MSP430. These chips usually include SPI controllers capable of running in either master or slave mode. In-system programmable AVR controllers (including blank ones) can be programmed using SPI.[12]

Chip or FPGA based designs sometimes use SPI to communicate between internal components; on-chip real estate can be as costly as its on-board cousin. And for high-performance systems, FPGAs sometimes use SPI to interface as a slave to a host, as a master to sensors, or for flash memory used to bootstrap if they are SRAM-based.

The full-duplex capability makes SPI very simple and efficient for single master/single slave applications. Some devices use the full-duplex mode to implement an efficient, swift data stream for applications such as digital audio, digital signal processing, or telecommunications channels, but most off-the-shelf chips stick to half-duplex request/response protocols.

Variations

[edit]SPI implementations have a wide variety of protocol variations. Some devices are transmit-only; others are receive-only. Slave selects are sometimes active-high rather than active-low. Some devices send the least-significant bit first. Signal levels depend entirely on the chips involved. And while the baseline SPI protocol has no command codes, every device may define its own protocol of command codes. Some variations are minor or informal, while others have an official defining document and may be considered to be separate but related protocols.

Original definition

[edit]Motorola in 1983 listed[13] three 6805 8-bit microcomputers that have an integrated "Serial Peripheral Interface", whose functionality is described in a 1984 manual.[14]

AN991

[edit]Motorola's 1987 Application Node AN991 "Using the Serial Peripheral Interface to Communicate Between Multiple Microcomputers"[15] (now under NXP, last revised 2002[5]) informally serves as the "official" defining document for SPI.

Timing variations

[edit]Some devices have timing variations from Motorola's CPOL/CPHA modes. Sending data from slave to master may use the opposite clock edge as master to slave. Devices often require extra clock idle time before the first clock or after the last one, or between a command and its response.

Some devices have two clocks, one to read data, and another to transmit it into the device. Many of the read clocks run from the slave select line.

Transmission size

[edit]Different transmission word sizes are common. Many SPI chips only support messages that are multiples of 8 bits. Such chips can not interoperate with the JTAG or SGPIO protocols, or any other protocol that requires messages that are not multiples of 8 bits.

No slave select

[edit]Some devices do not use slave select, and instead manage protocol state machine entry/exit using other methods.

Connectors

[edit]Anyone needing an external connector for SPI defines their own or uses another standard connection such as: UEXT, Pmod, various JTAG connectors, Secure Digital card socket, etc.

Flow control

[edit]Some devices require an additional flow control signal from slave to master, indicating when data is ready. This leads to a 5-wire protocol instead of the usual 4. Such a ready or enable signal is often active-low, and needs to be enabled at key points such as after commands or between words. Without such a signal, data transfer rates may need to be slowed down significantly, or protocols may need to have dummy bytes inserted, to accommodate the worst case for the slave response time. Examples include initiating an ADC conversion, addressing the right page of flash memory, and processing enough of a command that device firmware can load the first word of the response. (Many SPI masters do not support that signal directly, and instead rely on fixed delays.)

SafeSPI

[edit]SafeSPI[16] is an industry standard for SPI in automotive applications. Its main focus is the transmission of sensor data between different devices.

High reliability modifications

[edit]In electrically noisy environments, since SPI has few signals, it can be economical to reduce the effects of common mode noise by adapting SPI to use low-voltage differential signaling.[17] Another advantage is that the controlled devices can be designed to loop-back to test signal integrity.[18]

Intelligent SPI controllers

[edit]A Queued Serial Peripheral Interface (QSPI; different to but has same abbreviation as Quad SPI described in § Quad SPI) is a type of SPI controller that uses a data queue to transfer data across an SPI bus.[19] It has a wrap-around mode allowing continuous transfers to and from the queue with only intermittent attention from the CPU. Consequently, the peripherals appear to the CPU as memory-mapped parallel devices. This feature is useful in applications such as control of an A/D converter. Other programmable features in Queued SPI are chip selects and transfer length/delay.

SPI controllers from different vendors support different feature sets; such direct memory access (DMA) queues are not uncommon, although they may be associated with separate DMA engines rather than the SPI controller itself, such as used by Multichannel Buffered Serial Port (MCBSP).[note 6] Most SPI master controllers integrate support for up to four slave selects,[note 7] although some require slave selects to be managed separately through GPIO lines.

Note that Queued SPI is different from Quad SPI, and some processors even confusingly allow a single "QSPI" interface to operate in either quad or queued mode![20]

Microwire

[edit]Microwire,[21] often spelled μWire, is essentially a predecessor of SPI and a trademark of National Semiconductor. It's a strict subset of SPI: half-duplex, and using SPI mode 0. Microwire chips tend to need slower clock rates than newer SPI versions; perhaps 2 MHz vs. 20 MHz. Some Microwire chips also support a three-wire mode.

Microwire/Plus

[edit]Microwire/Plus[22] is an enhancement of Microwire and features full-duplex communication and support for SPI modes 0 and 1. There was no specified improvement in serial clock speed.

Three-wire

[edit]Three-wire variants of SPI restricted to a half-duplex mode use a single bidirectional data line called SISO (slave out/slave in) or MOMI (master out/master in) instead of SPI's two unidirectional lines (MOSI and MISO). Three-wire tends to be used for lower-performance parts, such as small EEPROMs used only during system startup, certain sensors, and Microwire. Few SPI controllers support this mode, although it can be easily bit-banged in software.

Dual SPI

[edit]For instances where the full-duplex nature of SPI is not used, an extension uses both data pins in a half-duplex configuration to send two bits per clock cycle. Typically a command byte is sent requesting a response in dual mode, after which the MOSI line becomes SIO0 (serial I/O 0) and carries even bits, while the MISO line becomes SIO1 and carries odd bits. Data is still transmitted most-significant bit first, but SIO1 carries bits 7, 5, 3 and 1 of each byte, while SIO0 carries bits 6, 4, 2 and 0.

This is particularly popular among SPI ROMs, which have to send a large amount of data, and comes in two variants:[23][24]

- Dual read sends the command and address from the master in single mode, and returns the data in dual mode.

- Dual I/O sends the command in single mode, then sends the address and return data in dual mode.

Quad SPI

[edit]Quad SPI (QSPI; different to but has same abbreviation as Queued-SPI described in § Intelligent SPI controllers) goes beyond dual SPI, adding two more I/O lines (SIO2 and SIO3) and sends 4 data bits per clock cycle. Again, it is requested by special commands, which enable quad mode after the command itself is sent in single mode.[23][24]

- SQI Type 1

- Commands sent on single line but addresses and data sent on four lines

- SQI Type 2

- Commands and addresses sent on a single line but data sent/received on four lines

QPI/SQI

[edit]Further extending quad SPI, some devices support a "quad everything" mode where all communication takes place over 4 data lines, including commands.[25] This is variously called "QPI"[24] (not to be confused with Intel QuickPath Interconnect) or "serial quad I/O" (SQI)[26]

This requires programming a configuration bit in the device and requires care after reset to establish communication.

Double data rate

[edit]In addition to using multiple lines for I/O, some devices increase the transfer rate by using double data rate transmission.[27][28]

JTAG

[edit]Although there are some similarities between SPI and the JTAG (IEEE 1149.1-2013) protocol, they are not interchangeable. JTAG is specifically intended to provide reliable test access to the I/O pins from an off-board controller with less precise signal delay and skew parameters, while SPI has many varied applications. While not strictly a level sensitive interface, the JTAG protocol supports the recovery of both setup and hold violations between JTAG devices by reducing the clock rate or changing the clock's duty cycles. Consequently, the JTAG interface is not intended to support extremely high data rates.[29]

SGPIO

[edit]SGPIO is essentially another (incompatible) application stack for SPI designed for particular backplane management activities.[citation needed] SGPIO uses 3-bit messages.

Intel's Enhanced Serial Peripheral Interface

[edit]Intel has developed a successor to its Low Pin Count (LPC) bus that it calls the Enhanced Serial Peripheral Interface (eSPI) bus. Intel aims to reduce the number of pins required on motherboards and increase throughput compared to LPC, reduce the working voltage to 1.8 volts to facilitate smaller chip manufacturing processes, allow eSPI peripherals to share SPI flash devices with the host (the LPC bus did not allow firmware hubs to be used by LPC peripherals), tunnel previous out-of-band pins through eSPI, and allow system designers to trade off cost and performance.[30][31]

An eSPI bus can either be shared with SPI devices to save pins or be separate from an SPI bus to allow more performance, especially when eSPI devices need to use SPI flash devices.[30]

This standard defines an Alert# signal that is used by an eSPI slave to request service from the master. In a performance-oriented design or a design with only one eSPI slave, each eSPI slave will have its Alert# pin connected to an Alert# pin on the eSPI master that is dedicated to each slave, allowing the eSPI master to grant low-latency service, because the eSPI master will know which eSPI slave needs service and will not need to poll all of the slaves to determine which device needs service. In a budget design with more than one eSPI slave, all of the Alert# pins of the slaves are connected to one Alert# pin on the eSPI master in a wired-OR connection, which requires the master to poll all the slaves to determine which ones need service when the Alert# signal is pulled low by one or more peripherals that need service. Only after all of the devices are serviced will the Alert# signal be pulled high due to none of the eSPI slaves needing service and therefore pulling the Alert# signal low.[30]

This standard allows designers to use 1-bit, 2-bit, or 4-bit communications at speeds from 20 to 66 MHz to further allow designers to trade off performance and cost.[30]

Communications that were out-of-band of LPC like general-purpose input/output (GPIO) and System Management Bus (SMBus) should be tunneled through eSPI via virtual wire cycles and out-of-band message cycles respectively in order to remove those pins from motherboard designs using eSPI.[30]

This standard supports standard memory cycles with lengths of 1 byte to 4 kilobytes of data, short memory cycles with lengths of 1, 2, or 4 bytes that have much less overhead compared to standard memory cycles, and I/O cycles with lengths of 1, 2, or 4 bytes of data which are low overhead as well. This significantly reduces overhead compared to the LPC bus, where all cycles except for the 128-byte firmware hub read cycle spends more than one-half of all of the bus's throughput and time in overhead. The standard memory cycle allows a length of anywhere from 1 byte to 4 kilobytes in order to allow its larger overhead to be amortised over a large transaction. eSPI slaves are allowed to initiate bus master versions of all of the memory cycles. Bus master I/O cycles, which were introduced by the LPC bus specification, and ISA-style DMA including the 32-bit variant introduced by the LPC bus specification, are not present in eSPI. Therefore, bus master memory cycles are the only allowed DMA in this standard.[30]

eSPI slaves are allowed to use the eSPI master as a proxy to perform flash operations on a standard SPI flash memory slave on behalf of the requesting eSPI slave.[30]

64-bit memory addressing is also added, but is only permitted when there is no equivalent 32-bit address.[30]

The Intel Z170 chipset can be configured to implement either this bus or a variant of the LPC bus that is missing its ISA-style DMA capability and is underclocked to 24 MHz instead of the standard 33 MHz.[32]

The eSPI bus is also adopted by AMD Ryzen chipsets.

Development tools

[edit]Single-board computers

[edit]Single-board computers may provide pin access to SPI hardware units. For instance, the Raspberry Pi's J8 header exposes at least two SPI units that can be used via Linux drivers or python.

USB to SPI adapters

[edit]There are a number of USB adapters that allow a desktop PC or smartphone with USB to communicate with SPI chips (e.g. CH341A/B[33] based or FT221xs[34]). They are used for embedded systems, chips (FPGA, ASIC, and SoC) and peripheral testing, programming and debugging. Many of them also provide scripting or programming capabilities (e.g. Visual Basic, C/C++, VHDL) and can be used with open source programs like flashrom, IMSProg, SNANDer or avrdude for flash, EEPROM, bootloader and BIOS programming.

The key SPI parameters are: the maximum supported frequency for the serial interface, command-to-command latency, and the maximum length for SPI commands. It is possible to find SPI adapters on the market today that support up to 100 MHz serial interfaces, with virtually unlimited access length.

SPI protocol being a de facto standard, some SPI host adapters also have the ability of supporting other protocols beyond the traditional 4-wire SPI (for example, support of quad-SPI protocol or other custom serial protocol that derive from SPI[35]).

Protocol analyzers

[edit]Logic analyzers are tools which collect, timestamp, analyze, decode, store, and view the high-speed waveforms, to help debug and develop. Most logic analyzers have the capability to decode SPI bus signals into high-level protocol data with human-readable labels.

Oscilloscopes

[edit]SPI waveforms can be seen on analog channels (and/or via digital channels in mixed-signal oscilloscopes).[36] Most oscilloscope vendors offer optional support for SPI protocol analysis (both 2-, 3-, and 4-wire SPI) with triggering.

Alternative terminology

[edit]Various alternative abbreviations for the four common SPI signals are used. (This section omits overbars indicating active-low.)

- Serial clock

- SCK, SCLK, CLK, SCL

- Master Out Slave In (MOSI)

- SIMO, MTSR, SPID - correspond to MOSI on both master and slave devices, connects to each other

- SDI, DI, DIN, SI, SDA - on slave devices; various abbreviations for serial data in; connects to MOSI on master

- SDO, DO, DOUT, SO - on master devices; various abbreviations for serial data out; connects to MOSI on slave

- COPI, PICO for peripheral and controller,[37][38] or COTI for controller and target[39]

- Master In Slave Out (MISO)

- Slave Select (SS)

- Chip select (CS)

- CE (chip enable)

- Historical: SSEL, NSS, /SS, SS#

Microchip uses host and client though keeps the abbreviation MOSI and MISO.[40]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The earliest definitive mention of a "Serial Peripheral Interface" in bitsavers archives of Motorola manuals is from 1983 (see § Original definition). While some sources on the web allege that Motorola introduced SPI when 68000 was introduced in 1979, however many of those appear to be citogenesis or speculation, and Motorola's 1983 68000 manual has no mention of "Serial Peripheral Interface", so the alleged 1979 date does not seem to be reliable information. Please only add a specific design_date if you have a definitive source from Motorola around then.

- ^ Some slaves require a falling edge of the Slave Select signal to initiate an action. An example is the Maxim MAX1242 ADC, which starts conversion on a high→low transition.

- ^ a b Not to be confused with the SDIO (Serial Data I/O) line of the half-duplex implementation of SPI sometimes also called "3-wire" SPI. Here e.g. MOSI (via a resistor) and MISO (no resistor) of a master is connected to the SDIO line of a slave.

- ^ Peripherals may allow or require a particular number (or any number) of transfer bytes while selected, as specified in their datasheet.

- ^ Left-shifts are used because SPI normally transmits the most-significant bit first. Right-shifts could instead be used to transfer least-significant bit first.

- ^ Such as with the MultiChannel Serial Port Interface, or McSPI, used in Texas Instruments OMAP chips. (https://www.ti.com/product/OMAP3530)

- ^ Such as the SPI controller on Atmel AT91 chips like the at91sam9G20, which is much simpler than TI's McSPI.

References

[edit]- ^ Stoicescu, Alin (2018). "Getting Started with SPI" (PDF). Microchip.

- ^ "What is Serial Synchronous Interface (SSI)?". Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ^ a b c Better SPI Bus Design in 3 Steps

- ^ SPI Block Guide v3.06; Motorola/Freescale/NXP; 2003.

- ^ a b "AN991/D: Using the Serial Peripheral Interface to Communicate Between Multiple Microcomputers" (PDF). NXP. 2004 [1994]. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-04-04. Retrieved 2021-10-14.

- ^ "TMS320x281x Serial Peripheral Interface Reference Guide". Texas Instruments. 2002. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Maxim-IC application note 3947: "Daisy-Chaining SPI Devices"

- ^ a b Gammon, Nick (2013-03-23). "Gammon Forum : Electronics : Microprocessors : Using a 74HC165 input shift register". Gammon Forum. Archived from the original on 2023-07-29. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ a b Gammon, Nick (2012-01-31). "Gammon Forum : Electronics : Microprocessors : Using a 74HC595 output shift register as a port-expander". Gammon Forum. Archived from the original on 2023-07-14. Retrieved 2023-08-03.

- ^ Interfaces, 1977, pp. 80, 84

- ^ "Serial-Control Multiplexer Expands SPI Chip Selects" (PDF). Premier Farnell. 2001-07-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-19.

- ^ "AVR910 - In-system programming" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-03-02.

- ^ components :: motorola :: dataBooks :: 1983 Motorola 8-Bit Microprocessor and Peripheral Data.

- ^ motorola :: dataBooks :: 1984 Motorola Single-Chip Microcomputer Data.

- ^ "Using the Serial Peripheral Interface to Communicate Between Multiple Microcomputers" (PDF). Bitsavers.

- ^ SafeSPI.org

- ^ "Transmitting SPI over LVDS Interfaces" (PDF). Texas Instruments. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ "SPI Master Loopback Example". Nordic Semiconductor. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ "Freescale Semiconductor, Inc. - QSM - Queued Serial Module - Reference Manual" (PDF). NXP. 1996 [1991]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-24.

- ^ "Quad-SPI Brings Fast Parallel Data Transmission". Cadence Design Systems. 2023-01-11. Archived from the original on 2023-06-01. Retrieved 2023-06-30.

- ^ MICROWIRE Serial Interface National Semiconductor Application Note AN-452

- ^ MICROWIRE/PLUS Serial Interface for COP800 Family National Semiconductor Application Note AN-579

- ^ a b "W25Q16JV 3V 16M-bit serial flash memory with Dual/Quad SPI" (PDF) (data sheet). Revision D. Winbond. 12 August 2016. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- ^ a b c "D25LQ64 1.8V Uniform Sector Dual and Quad SPI Flash" (PDF) (data sheet). version 0.1. GigaDevice. 11 February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2017. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- ^ "QuadSPI flash: Quad SPI mode vs. QPI mode". NXP community forums. December 2014. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

- ^ "SST26VF032B / SST26VF032BA 2.5V/3.0V 32 Mbit Serial Quad I/O (SQI) Flash Memory" (PDF) (Data sheet). version E. Microchip, Inc. 2017. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- ^ Patterson, David (May 2012). "Quad Serial Peripheral Interface (QuadSPI) Module Updates" (PDF) (Application note). Freescale Semiconductor. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ Pell, Rich (13 October 2011). "Improving performance using SPI-DDR NOR flash memory". EDN.

- ^ IEEE 1149.1-2013

- ^ a b c d e f g h Enhanced Serial Peripheral Interface (eSPI) Interface Base Specification (for Client and Server Platforms) (PDF) (Report). Revision 1.0. Intel. January 2016. Document number 327432-004. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ^ Enhanced Serial Peripheral Interface (eSPI) Interface Specification (for Client Platforms) (PDF) (Report). Revision 0.6. Intel. May 2012. Document Number 327432-001EN. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ^ "Intel® 100 Series Chipset Family PCH Datasheet, Vol. 1" (PDF). Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- ^ "USB Bridge Controller CH341 with UART, SPI and I2C". WCH. Retrieved 27 February 2025.

- ^ "USB to SPI converter". FTDI. 2 August 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ SPI Storm – Serial Protocol Host Adapter with support of custom serial protocols, Byte Paradigm.

- ^ "N5391B I²C and SPI Protocol Triggering and Decode for Infiniium scopes".

- ^ a b SPI; OSHWA.

- ^ a b "Product Overview - Translate Voltages for SPI" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-03-17.

- ^ a b "Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) Devices". NXP. Archived from the original on 2023-06-01. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Stoicescu, Alin. "Getting Started with Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI)". Microchip Technology. Archived from the original on 2023-12-21. Retrieved 2023-12-21.

External links

[edit]Serial Peripheral Interface

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

History and Origins

The Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) was developed by Motorola in the mid-1980s as a straightforward synchronous serial communication protocol intended for short-distance data exchange between integrated circuits on the same circuit board. This interface emerged to meet the growing demand for efficient, full-duplex serial links in early embedded systems, where simplicity and speed were prioritized over long-range capabilities. Unlike more complex protocols, SPI was engineered for minimal overhead, using a master-slave architecture to synchronize data transfer via a dedicated clock line. A pivotal document in SPI's formalization was Motorola's Application Note AN991, originally published in 1987, which provided the first detailed description of the protocol. Titled "Using the Serial Peripheral Interface to Communicate Between Multiple Microcomputers," it outlined the original four-wire configuration: Serial Clock (SCK) for synchronization, Master Out Slave In (MOSI) for data from master to slave, Master In Slave Out (MISO) for data from slave to master, and Slave Select (SS) to designate active devices. The note demonstrated SPI's implementation in hardware on the MC68HC05C4 microcontroller and in software on the MC68705R3, highlighting its versatility for inter-microcomputer communication without requiring additional protocol layers.[8] SPI saw initial adoption within Motorola's product lineup, notably in the 68HC11 family of 8-bit microcontrollers introduced in 1984, where it served as a built-in peripheral for interfacing with sensors, memory, and other ICs. By the late 1980s, the protocol expanded to other vendors, fostering broader interoperability. Although never ratified as an official standard by bodies like IEEE or ISO, SPI evolved into a de facto industry norm by the 1990s, driven by its integration into countless embedded applications and the absence of licensing restrictions. By 1990, it had achieved widespread use in microcomputer-based systems for tasks requiring reliable, high-speed local data transfer.[9][10]Basic Principles

The Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) is a synchronous serial communication protocol designed for short-distance data exchange between a microcontroller and peripheral devices, such as sensors or memory chips. It operates in full-duplex mode, enabling simultaneous transmission and reception of data over dedicated lines.[11][12] At its core, SPI employs four primary signal lines: the Serial Clock (SCK), which is generated by the master device to synchronize data transfer; Master Out Slave In (MOSI), for data output from the master to the slave; Master In Slave Out (MISO), for data input from the slave to the master; and Slave Select (SS) or Chip Select (CS), which activates a specific slave device. These lines facilitate a straightforward, hardware-based interface without requiring complex protocol overhead.[12][11] SPI follows a master-slave architecture, where a single master device—typically a microcontroller—controls the communication by providing the clock signal and initiating transfers, while one or more slave devices respond passively without generating their own clock. This setup ensures deterministic timing and simplifies implementation, as slaves only need to detect the clock and select signals to participate. The full-duplex nature allows the master and slave to exchange data bits concurrently during each clock cycle, doubling the effective throughput compared to half-duplex alternatives.[12][11][13] The protocol is optimized for short-distance connections, commonly spanning within a single printed circuit board (PCB) or up to approximately 10 meters with appropriate buffering to mitigate signal degradation. Unlike protocols with built-in addressing schemes, SPI lacks formal device addressing; instead, the master selects slaves individually using dedicated SS lines or through software-based decoding on a shared line, enabling point-to-point or multi-slave bus configurations.[11][14][12]Operation

Data Transmission Protocol

The Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) operates as a synchronous, full-duplex master-slave protocol for serial data exchange between integrated circuits, where the master device controls the timing and flow of communication using four primary signal lines: serial clock (SCK), master out slave in (MOSI), master in slave out (MISO), and slave select (SS).[12] The master initiates each transaction by asserting the SS line low for the specific slave device, signaling the start of data transfer and enabling the slave to prepare for reception.[13] This selection mechanism ensures that only the targeted slave responds, while others remain inactive.[15] Once initiated, the master generates the SCK signal to synchronize the bit stream, shifting data serially in frames that are typically 8 bits long, with transmission occurring most significant bit (MSB) first.[15] On the MOSI line, the master outputs its data bits, which the slave samples on designated clock edges; concurrently, the slave outputs its response data on the MISO line, which the master samples on the same or corresponding edges, facilitating simultaneous bidirectional transfer.[12] This full-duplex capability allows efficient data exchange without waiting for unidirectional cycles, though the exact sampling edges depend on the configured mode without altering the overall protocol flow.[13] In the idle state, the SS line remains high and the clock idles at the level defined by the clock polarity (CPOL), preventing any unintended data activity and maintaining a stable bus condition.[15] A transaction concludes when the master deasserts the SS line high, which resets the slave's internal shift registers and counters, preparing it for the next selection.[12] This deassertion marks the end of the frame and ensures proper synchronization for subsequent operations.[13] SPI lacks built-in error detection or correction mechanisms, such as cyclic redundancy checks (CRC) or hardware acknowledgments, making it a lightweight protocol that depends on overlying software layers for verifying data integrity and handling transmission errors.[16] This design prioritizes speed and simplicity over robustness, suitable for short-distance, low-error environments like on-chip or board-level communications.[16]Clock Polarity and Phase

The Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) protocol incorporates two key configurable parameters for the serial clock (SCLK): clock polarity (CPOL) and clock phase (CPHA). These parameters define the clock's idle state and the timing of data sampling relative to clock edges, ensuring synchronization between the master and slave devices during transmission.[11][17] Clock polarity, denoted as CPOL, determines the default logic level of the SCLK line during the idle period, which occurs when the chip select (CS) signal is deasserted (high). A CPOL value of 0 configures the clock to idle low (logic 0), while CPOL = 1 sets it to idle high (logic 1). This polarity affects the initial state from which clock transitions occur when CS is asserted, influencing the overall waveform and compatibility with connected peripherals.[11][3] Clock phase, denoted as CPHA, specifies when data is captured (sampled) by the receiver relative to the clock edges. With CPHA = 0, data is sampled on the first clock edge after CS assertion—the leading edge—while the transmitter shifts data on the opposite (trailing) edge. For CPHA = 1, sampling occurs on the second clock edge—the trailing edge—with shifting on the leading edge. This distinction separates the setup phase (where data is prepared) from the capture phase (where it is read), preventing timing conflicts in bidirectional communication.[11][17][3] The combination of CPOL and CPHA yields four distinct operating configurations, conventionally labeled as SPI modes 0 through 3, each producing unique clock waveforms that dictate data validity windows. In mode 0 (CPOL=0, CPHA=0), the clock idles low; data is sampled on the rising edge and shifted on the falling edge, resulting in a waveform where the first rising edge captures the initial bit after CS assertion. Mode 1 (CPOL=0, CPHA=1) also idles low but samples on the falling edge and shifts on the rising edge, with data setup occurring before the first falling edge. For mode 2 (CPOL=1, CPHA=0), the clock idles high; sampling happens on the falling edge (first transition from high), with shifting on the rising edge. Finally, mode 3 (CPOL=1, CPHA=1) idles high, sampling on the rising edge and shifting on the falling edge, where the first rising edge follows an initial high-to-low transition. These waveforms ensure data stability during transfers, with the master initiating pulses to align bits across MOSI and MISO lines.[11][17][3] To maintain reliable operation, data must adhere to minimum setup and hold times around the sampling edges, as specified in device datasheets. Setup time is the duration data must be stable before the sampling edge, typically around 10 ns, while hold time requires stability after the edge, often exceeding 15 ns in some implementations to account for propagation delays. Clock cycle times must accommodate these, for example, supporting frequencies up to 10 MHz with periods of at least 100 ns in certain peripherals. Mismatches in these timings can lead to bit errors, necessitating careful configuration.[17][3] Among the modes, mode 0 (CPOL=0, CPHA=0) serves as the most common default in many systems due to its alignment with natural clock behaviors in CMOS logic, promoting broad interoperability unless a peripheral datasheet specifies otherwise. Masters are often designed to support all four modes for flexibility, while slaves may be fixed to one or two.[17][3]Mode Numbers and Valid Sequences

The Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) defines four standard operating modes based on the combination of clock polarity (CPOL) and clock phase (CPHA) settings, which determine the clock's idle state and the timing of data sampling and shifting. These modes ensure compatibility between master and slave devices by standardizing how data is captured relative to clock edges.[11][3] In Mode 0, CPOL is 0 and CPHA is 0, resulting in a clock that idles low and samples data on the leading (rising) edge while shifting data on the trailing (falling) edge. Mode 1 sets CPOL to 0 and CPHA to 1, with the clock idling low but sampling data on the trailing (falling) edge and shifting on the leading (rising) edge. Mode 2 uses CPOL=1 and CPHA=0, where the clock idles high and samples data on the leading (falling) edge, shifting on the trailing (rising) edge. Finally, Mode 3 combines CPOL=1 and CPHA=1, with the clock idling high, sampling on the trailing (rising) edge, and shifting on the leading (falling) edge.[11][3][5] The following table summarizes the four SPI modes:| Mode | CPOL | CPHA | Idle Clock Level | Data Sample Edge | Data Shift Edge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | Low | Rising (leading) | Falling (trailing) |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | Low | Falling (trailing) | Rising (leading) |

| 2 | 1 | 0 | High | Falling (leading) | Rising (trailing) |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | High | Rising (trailing) | Falling (leading) |

| Master Mode | Compatible Slave Modes | Incompatible Slave Modes |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1, 2, 3 |

| 1 | 1 | 0, 2, 3 |

| 2 | 2 | 0, 1, 3 |

| 3 | 3 | 0, 1, 2 |

Chip Select and Interrupts

The Chip Select (CS), also known as Slave Select (SS), serves as an active-low control signal in the Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) to designate and enable a specific slave device for data exchange with the master.[18] The master asserts the CS line low to activate the targeted slave, initiating the transaction, while deasserting it high concludes the exchange and places the slave's output in a high-impedance state to prevent bus contention.[19] This mechanism ensures synchronous, full-duplex communication occurs exclusively between the master and the selected slave during the assertion period.[20] In multi-slave configurations, the master utilizes distinct CS lines, each connected to a general-purpose input/output (GPIO) pin, to individually address slaves without requiring additional hardware decoding.[18] Software on the master manages these lines by asserting only the CS corresponding to the intended slave for each transaction, thereby supporting scalable bus architectures while maintaining isolation between devices.[19] Interrupts in SPI primarily support event-driven operation within controller modules but extend to basic signaling for transaction coordination between master and slave. From the master to the slave, the falling edge of the CS signal can generate an interrupt in the slave if supported by the hardware, alerting it to prepare for incoming data or to begin transmission synchronization.[19] This edge detection leverages the CS assertion to trigger hardware interrupts for receive or transmit buffer management in the slave.[18] Slave-to-master signaling lacks a uniform protocol in core SPI specifications, relying instead on implementation-specific techniques such as toggling the Master In Slave Out (MISO) line with predefined patterns to indicate data availability or using a dedicated interrupt request (IRQ) line.[20] A prevalent method involves the slave asserting a separate GPIO or IRQ pin low when data is ready for transmission, which the master monitors via its own interrupt handler to prompt an SPI read operation. Overall, SPI's interrupt mechanisms for device coordination are not standardized beyond module-level flags for events like transfer completion or buffer status, resulting in vendor-dependent approaches that differ across microcontroller implementations from manufacturers like Texas Instruments and Microchip Technology.[18][19] This flexibility accommodates diverse applications but requires careful design consideration for interoperability.[20]Software Implementation

The Serial Peripheral Interface (SPI) is commonly implemented in software through dedicated hardware controllers or bit-banging techniques, depending on the microcontroller's capabilities and application requirements. Hardware SPI controllers are integrated peripherals in many microcontrollers, providing efficient, high-speed communication without significant CPU overhead. For instance, the AVR family from Microchip includes an SPI module configurable via registers like SPCR for mode selection (e.g., master/slave, clock polarity/phase) and SPSR/SPCR for baud rate control, supporting clock rates derived from the system clock.[21] Similarly, STM32 microcontrollers from STMicroelectronics feature SPI peripherals with registers such as SPI_CR1 for mode and baud rate settings, and SPI_CR2 for operational control, enabling full-duplex transfers. These controllers can achieve baud rates up to 100 Mbps in advanced implementations, though typical rates range from 1 to 50 MHz to ensure reliable signal integrity across short distances.[11] The baud rate in hardware controllers is calculated based on the system clock and prescaler values; for example, , where is the peripheral clock frequency and the prescaler divides it to set the desired SPI clock speed.[22] This configuration allows developers to match the clock to peripheral device specifications, with common prescalers yielding rates like 8 MHz from a 16 MHz clock using a prescaler of 1. In STM32 devices, the formula aligns similarly, using the APB bus clock divided by a programmable prescaler (powers of 2 from 2 to 256).[23] When hardware controllers are unavailable or flexibility is needed (e.g., on pin-constrained devices), bit-banging emulates SPI using general-purpose I/O (GPIO) pins to toggle the clock (SCK), master-out-slave-in (MOSI), master-in-slave-out (MISO), and slave select (SS) lines manually in software. This approach is simple to implement but CPU-intensive, as it requires the processor to handle timing and data shifting for each bit, limiting throughput to a fraction of hardware capabilities—often below 1 MHz on low-end MCUs.[24] Precise timing is critical in bit-banging to avoid protocol violations; developers typically insert delays between pin changes or use hardware timers for more accurate clock generation, as imprecise delays can cause data misalignment or missed edges.[25] A basic pseudocode example for an 8-bit full-duplex transfer in master mode (assuming mode 0: CPOL=0, CPHA=0) illustrates the process:void spi_transfer(uint8_t tx_data, uint8_t* rx_data) {

*rx_data = 0;

digital_write(SS, LOW); // Assert slave select

for (int i = 7; i >= 0; i--) {

digital_write(MOSI, (tx_data >> i) & 1); // Set MOSI bit

delay_us(half_period); // Setup time (clock low duration)

digital_write(SCK, HIGH); // Clock high (rising edge)

*rx_data |= (digital_read(MISO) << i); // Sample MISO on rising edge

delay_us(half_period); // Clock high duration

digital_write(SCK, LOW); // Clock low (falling edge)

}

digital_write(SS, HIGH); // Deassert slave select

}

void spi_transfer(uint8_t tx_data, uint8_t* rx_data) {

*rx_data = 0;

digital_write(SS, LOW); // Assert slave select

for (int i = 7; i >= 0; i--) {

digital_write(MOSI, (tx_data >> i) & 1); // Set MOSI bit

delay_us(half_period); // Setup time (clock low duration)

digital_write(SCK, HIGH); // Clock high (rising edge)

*rx_data |= (digital_read(MISO) << i); // Sample MISO on rising edge

delay_us(half_period); // Clock high duration

digital_write(SCK, LOW); // Clock low (falling edge)

}

digital_write(SS, HIGH); // Deassert slave select

}

half_period tuned to half the desired clock period for a 50% duty cycle (e.g., via a timer interrupt for better precision).[24]

To simplify development, libraries abstract these low-level details. The Arduino SPI library (SPI.h) provides functions like SPI.beginTransaction() for configuring modes and rates on supported boards, handling register setup internally.[26] On Linux systems, the Python spidev module interfaces with the kernel's SPI driver for user-space access, offering methods like xfer() for data exchange and max_speed_hz for baud rate setting.[27] These tools enable rapid prototyping while leveraging underlying hardware or software emulation.