Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

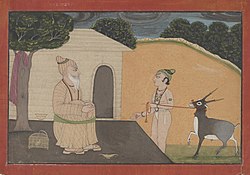

Guru–shishya tradition

View on Wikipedia

The guru–shishya tradition, or parampara (lit. 'lineage'), denotes a succession of teachers and disciples in Indian-origin religions such as Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism and Buddhism (including Tibetan and Zen traditions). Each parampara belongs to a specific sampradaya, and may have its own gurukulas for teaching, which might be based at akharas, gompas, mathas, viharas or temples. It is the tradition of spiritual relationship and mentoring where teachings are transmitted from a guru, teacher, (Sanskrit: गुरु) or lama, to a śiṣya (Sanskrit: शिष्य, disciple), shramana (seeker), or chela (follower), after the formal diksha (initiation). Such knowledge, whether agamic, spiritual, scriptural, architectural, musical, arts or martial arts, is imparted through the developing relationship between the guru and the disciple.

It is considered that this relationship, based on the genuineness of the guru and the respect, commitment, devotion and obedience of the student, is the best way for subtle or advanced knowledge to be conveyed. The student eventually masters the knowledge that the guru embodies.

Etymology

[edit]Guru–shishya means "succession from guru to disciple".

Paramparā (Sanskrit: परम्परा, paramparā) literally means an uninterrupted row or series, order, succession, continuation, mediation, tradition.[1] In the traditional residential form of education, the shishya remains with their guru as a family member and gets the education as a true learner.[2]

History

[edit]In the early oral traditions of the Upanishads, the guru–shishya relationship had evolved into a fundamental component of Hinduism. The term "Upanishad" derives from the Sanskrit words "upa" (near), "ni" (down) and "ṣad" (to sit) — so it means "sitting down near" a spiritual teacher to receive instruction. The relationship between Krishna and Arjuna in the Mahabharata, and between Rama and Hanuman in the Ramayana, are examples of Bhakti. In the Upanishads, gurus and disciples appear in a variety of settings (e.g. a husband answering questions about immortality; a teenage boy being taught by Yama, Hinduism's Lord of Death). Sometimes the sages are women, and the instructions may be sought by kings.[citation needed]

In the Vedas, the knowledge of Brahman (brahmavidya) is communicated from guru to shishya by oral tradition (sabda).[3] Mundaka Upanishad describes receiving spiritual knowledge in verse 1.2.12:[4]

In order to learn the transcendental science, one must submissively approach a bona fide spiritual master, who is coming in disciplic succession and is fixed in the Absolute Truth.

— Mundaka Upanishad, Verse 1.2.12

The disciplic succession (guru–parampara) ensures that the knowledge is preserved unaltered through a succession line of teachers.[5]

Arrangements

[edit]Sampradaya, Parampara, Gurukula and Akhara

[edit]Traditionally the word used for a succession of teachers and disciples in ancient Indian culture is parampara (paramparā in IAST).[6][7] In the parampara system, knowledge (in any field) is believed to be passed down through successive generations. The Sanskrit word figuratively means "an uninterrupted series or succession". Sometimes defined as "the passing down of Vedic knowledge", it is believed to be always entrusted to the ācāryas.[7] An established parampara is often called sampradāya, or school of thought. For example, in Vaishnavism a number of sampradayas are developed following a single teacher, or an acharya. While some argue for freedom of interpretation others maintain that "Although an ācārya speaks according to the time and circumstance in which he appears, he upholds the original conclusion, or siddhānta, of the Vedic literature."[7] This parampara ensures continuity of sampradaya, transmission of dharma, knowledge and skills.

Akhara is a place of practice with facilities for boarding, lodging and training, both in the context of Indian martial artists or a Sampradaya monastery for religious renunciates.[8] For example, in the context of the Dashanami Sampradaya sect, the word denotes both martial arts and religious monastic aspects of the trident wielding martial regiment of renunciate sadhus.[9]

Common characteristics of the guru–shishya relationship

[edit]Within the broad spectrum of the Indian religions, the guru–shishya relationship can be found in numerous variant forms including tantra. Some common elements in this relationship include:

- Diksha (formal initiation): A formal recognition of this relationship, generally in a structured initiation ceremony where the guru accepts the initiate as a shishya and also accepts responsibility for the spiritual well-being and progress of the new shishya.

- Shiksha (transmission of knowledge): Sometimes this initiation process will include the conveying of specific esoteric wisdom and/or meditation techniques.

- Gurudakshina, where the shishya gives a gift to the guru as a token of gratitude, often the only monetary or otherwise fee that the student ever gives. Such tokens can be as simple as a piece of fruit or as serious as a thumb, as in the case of Ekalavya and his guru Dronacharya.

- Guru gotra, refers to the practice of adopting the name of guru or the parampara as one's gotra (surname) instead of gotra at birth. The disciples of same guru, especially in the same cohort, are referred to as guru bhrata (brother by virtue of having same guru) or guru bhagini (sister by virtue of having same guru).

In some paramparas there is never more than one active master at the same time in the same guruparamaparya (lineage),[12] while other paramparas might allow multiple simultaneous gurus at a time.

Titles of gurus

[edit]Gurunath is a form of salutation to revere the guru as god.

In paramapara, not only is the immediate guru revered, the three preceding gurus are also worshipped or revered. These are known variously as the kala-guru or as the "four gurus" and are designated as follows:[13]

- Guru: Refer to the immediate guru.

- Parama-guru: Refer to the founding guru of the specific parampara, e.g. for the Śankaracharyas this is Adi Śankara.

- Parātpara-guru: Refer to guru who is the source of knowledge for sampradaya or tradition, e.g. for the Śankaracharya's this is Vedavyāsa.

- Parameṣṭhi-guru: Refer to the highest guru, who has the power to bestow mokṣa, e.g. for the Śankaracharya's this is usually depicted as Lord Śhiva, being the highest guru.

Psychological aspects of relationship

[edit]The relation of Guru and Shishya is equated with that of a child in the womb of mother.[10] Rob Preece, in The Wisdom of Imperfection,[14] writes that while the teacher/disciple relationship can be an invaluable and fruitful experience, the process of relating to spiritual teachers also has its hazards.

As other authors had done before him,[15] Preece mentions the notion of transference to explain the manner in which the guru/disciple relationship develops from a more Western psychological perspective. He writes, "In its simplest sense transference occurs when unconsciously a person endows another with an attribute that actually is projected from within themselves". Preece further states that when we transfer an inner quality onto another person we may be giving that person a power over us as a consequence of the projection, carrying the potential for great insight and inspiration, but also the potential for great danger. "In giving this power over to someone else they have a certain hold and influence over us it is hard to resist, while we become enthralled or spellbound by the power of the archetype."[14]

Guru–shishya relationship by sampradaya

[edit]There is a variation in the level of authority that may be granted to the guru. The highest is that found in bhakti yoga, and the lowest is in the pranayama forms of yoga, such as the Sankara Saranam movement. Between these two there are many variations in degree and form of authority.[original research?]

Advaita Vedanta sampradaya

[edit]Advaita Vedānta requires anyone seeking to study Advaita Vedānta to do so from a guru (teacher). The guru must have the following qualities:[16]

- Śrotriya — must be learned in the Vedic scriptures and sampradaya[16]

- Brahmaniṣṭha — figuratively meaning "established in Brahman"; must have realised the oneness of Brahman in everything and in himself.[16]

The seeker must serve the guru and submit his questions with all humility so that doubt may be removed.[17] According to Advaita, the seeker will be able to attain liberation from the cycle of births and deaths (moksha).

Śruti sampradaya

[edit]The guru–shishya tradition plays an important part in the Shruti tradition of Vaidika dharma. The Hindus believe that the Vedas have been handed down through the ages from guru to shishya. The Vedas themselves prescribe for a young brahmachari to be sent to a Gurukul where the Guru (referred to also as acharya) teaches the pupil the Vedas and Vedangas. The pupil is also taught the Prayoga to perform yajnas. The term of stay varies (Manu Smriti says the term may be 12 years, 36 years or 48 years). After the stay at the Gurukul the brahmachari returns home after performing a ceremony called samavartana.

The word Śrauta is derived from the word Śruti meaning that which is heard. The Śrauta tradition is a purely oral handing down of the Vedas, but many modern Vedic scholars make use of books as a teaching tool.[18]

Shaktipat sampradaya

[edit]The guru passes his knowledge to his disciples by virtue of the fact that his purified consciousness enters into the selves of his disciples and communicates its particular characteristic. In this process the disciple is made part of the spiritual family (kula) – a family which is not based on blood relations but on people of the same knowledge.[19]

Bhakti yoga

[edit]The best known form of the guru–shishya relationship is that of bhakti. Bhakti (devotion) means surrender to God or guru. Bhakti extends from the simplest expression of devotion to the ego-destroying principle of prapatti, which is total surrender. The bhakti form of the guru–shishya relationship generally incorporates three primary beliefs or practices:

- Devotion to the guru as a divine figure or Avatar.[citation needed]

- The belief that such a guru has transmitted, or will impart moksha, diksha or shaktipat to the (successful) shishya.

- The belief that if the shishya's act of focusing their bhakti upon the guru is sufficiently strong and worthy, then some form of spiritual merit will be gained by the shishya.[citation needed]

Prapatti sampradaya

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2025) |

In the ego-destroying principle of prapatti (Sanskrit, "Throwing oneself down"), the level of the submission of the will of the shishya to the will of God or the guru is sometimes extreme, and is often coupled with an attitude of personal helplessness, self-effacement and resignation. This doctrine is perhaps best expressed in the teachings of the four Samayacharya saints, who shared a profound and mystical love of Siva expressed by:

- Deep humility and self-effacement, admission of sin and weakness;

- Total surrender to God as the only true refuge; and

- A relationship of lover and beloved known as bridal mysticism, in which the devotee is the bride and Siva the bridegroom.

In its most extreme form it sometimes includes:

- The assignment of all or many of the material possessions of the shishya to the guru.

- The strict and unconditional adherence by the shishya to all of the commands of the guru. An example is the legend that Karna silently bore the pain of a wasp stinging his thigh so as not to disturb his guru Parashurama.

- A system of various titles of implied superiority or deification which the guru assumes, and often requires the shishya to use whenever addressing the guru.

- The requirement that the shishya engage in various forms of physical demonstrations of affection towards the guru, such as bowing, kissing the hands or feet of the guru, and sometimes agreeing to various physical punishments as may sometimes be ordered by the guru.

- Sometimes the authority of the guru will extend to all aspects of the shishya's life, including sexuality, livelihood, social life, etc.

Often a guru will assert that he or she is capable of leading a shishya directly to the highest possible state of spirituality or consciousness, sometimes referred to within Hinduism as moksha. In the bhakti guru–shishya relationship the guru is often believed to have supernatural powers, leading to the deification of the guru.

Buddhism sampradaya

[edit]In the Pali Buddhist tradition, magae the Bhikkus are also known as Sekhas (SN XLVIII.53 Sekha Sutta).

In the Theravada Buddhist tradition, the teacher is a valued and honoured mentor worthy of great respect and a source of inspiration on the path to Enlightenment.[20] In the Tibetan tradition, however, the teacher is viewed as the very root of spiritual realisation and the basis of the entire path.[21] Without the teacher, it is asserted, there can be no experience or insight. The guru is seen as Buddha. In Tibetan texts, emphasis is placed upon praising the virtues of the guru. Tantric teachings include generating visualisations of the guru and making offerings praising the guru. The guru becomes known as the vajra (figuratively "diamond") guru, the one who is the source of initiation into the tantric deity. The disciple is asked to enter into a series of vows and commitments that ensure the maintenance of the spiritual link with the understanding that to break this link is a serious downfall.[citation needed]

In Vajrayana (tantric Buddhism) as the guru is perceived as the way itself. The guru is not an individual who initiates a person, but the person's own Buddha-nature reflected in the personality of the guru. In return, the disciple is expected to show great devotion to their guru, who he or she regards as one who possesses the qualities of a Bodhisattva. A guru is regarded as one which has not only mastered the words of the tradition, but one that with which the student has an intense personal relationship; thus, devotion is seen as the proper attitude toward the guru.[22]

The Dalai Lama, speaking of the importance of the guru, said: "Rely on the teachings to evaluate a guru: Do not have blind faith, but also no blind criticism." He also observed that the term 'living Buddha' is a translation of the Chinese words huo fuo.[23]

Order and service

[edit]In Indic religions namely Jainism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism selfless service to Guru, accepting and following all his/her orders carries very significant and valued part of relationship of Shishya (disciple) with his/her Guru.[10] Orders of Guru are referred as Guru Agya/Adnya/Hukam. Service of Guru is referred as Guru Seva.[24] In Sikhism, the scripture Adi Granth is considered to be last Guru hence the book is worshiped as like human Guru.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Monier Monier-Williams (1899). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 587(column a). OL 6534982M.

- ^ A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada Srimad Bhagavatam 7.12.1, The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1976, ISBN 0-912776-87-0

- ^ Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami 1976, p. 4-8.

- ^ Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami 1976, p. 7.

- ^ Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami 1976, p. 7-8.

- ^ Bg. 4.2 evaṁ paramparā-prāptam imaṁ rājarṣayo viduḥ - This supreme science was thus received through the chain of disciplic succession, and the saintly kings understood it in that way..

- ^ a b c Satsvarupa, dasa Goswami (1976). Readings in Vedit Literature: The Tradition Speaks for Itself. S.l.: Assoc Publishing Group. pp. 240 pages. ISBN 0-912776-88-9.

- ^ Akharas and Kumbh Mela What Is Hinduism?: Modern Adventures Into a Profound Global Faith, by Editors of Hinduism Today, Hinduism Today Magazine Editors. Published by Himalayan Academy Publications, 2007. ISBN 1-934145-00-9. 243-244.

- ^ James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 23–4. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8.

- ^ a b c Joshi, Ankur; Gupta, Rajen K. (2017). "Elementary education in Bharat (that is India): insights from a postcolonial ethnographic study of a Gurukul". International Journal of Indian Culture and Business Management. 15 (1): 100. doi:10.1504/IJICBM.2017.085390. ISSN 1753-0806.

- ^ Nandram, Sharda S.; Joshi, Ankur; Sukhada, N.A.; Dhital, Vishwanath (2021). "Delivering holistic education for contemporary times: Banasthali Vidyapith and the Gurukula system". International Journal of Business and Globalisation. 29 (2): 222. doi:10.1504/IJBG.2021.118235. ISSN 1753-3627.

- ^ Padoux, André. "The Tantric Guru" in David Gordon White (ed.) 2000. Tantra in Practice, p. 44. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press OCLC 43441625

- ^ Mahanirvana Tantra

- ^ a b Preece, Rob. "The teacher-student relationship" in The Wisdom of Imperfection: The Challenge of Individuation in Buddhist Life, Snow Lion Publications, 2006, ISBN 1-55939-252-5, p. 155 ff. At mudra.co.uk (author's website): Part 1 Archived 2003-08-07 at the Wayback Machine, Part 2 Archived 2008-06-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Dutch) Schnabel, Tussen stigma en charisma ("Between stigma and charisma"), 1982. Ch. V, p. 142, quoting Jan van der Lans, Volgelingen van de goeroe: Hedendaagse religieuze bewegingen in Nederland. Ambo, Baarn, 1981, ISBN 90-263-0521-4

(note: "overdracht" is the Dutch term for "transference") - ^ a b c Mundaka Upanishad 1.2.12

- ^ Bhagavad Gita 4.34

- ^ Hindu Dharma

- ^ Abhinavagupta: The Kula Ritual, as Elaborated in Chapter 29 of the Tantrāloka, John R. Dupuche, Page 131

- ^ Thurman, Robert A. F.; Huntington, John; Dina Bangdel (2003). Beginning the process: The Great Masters and Selecting a Teacher - The Guru-Disciple relationship; in: The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. London: Serindia Publications. ISBN 1-932476-01-6.

- ^ Dreyfus, Georges B. J. (2003). The sound of two hands clapping: the education of a Tibetan Buddhist monk. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 61–3. ISBN 0-520-23260-7.

- ^ Gross, Rita M. (1998). Soaring and settling: Buddhist perspectives on contemporary social and religious issues. London: Continuum. p. 184. ISBN 0-8264-1113-4.

- ^ "The Teacher - The Guru". Archived from the original on 2008-05-14.

- ^ Copeman, Jacob; Ikegame, Aya (2012). The Guru in South Asia: New Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-51019-6.

Sources

[edit]- Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami (1976). Readings In Vedic Literture.

Further reading

[edit]- Monika Horstmann, Heidi Rika Maria Pauwels, 2009, Patronage and Popularisation, Pilgrimage and Procession.

- Neuman, Daniel M. (1990). The life of music in north India: the organization of an artistic tradition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-57516-0.

- Leela Prasad, 2012, Poetics of Conduct: Oral Narrative and Moral Being in a South Indian Town.

- Federico Squarcini, 2011, Boundaries, Dynamics and Construction of Traditions in South Asia.

External links

[edit] Media related to Guru–shishya tradition at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Guru–shishya tradition at Wikimedia Commons