Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hinduism

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Hinduism (/ˈhɪnduˌɪzəm/)[1] is an umbrella term[2][3][a] for a range of Indian religious and spiritual traditions (sampradayas)[4][note 1] that are unified by adherence to the concept of dharma, a cosmic order maintained by its followers through rituals and righteous living,[5][b] as expounded in the Vedas.[c] The word Hindu is an exonym,[note 2] and while Hinduism has been called the oldest surviving religion in the world,[note 3] it has also been described by the modern term Sanātana Dharma (lit. 'eternal dharma').[note 4] Vaidika Dharma (lit. 'Vedic dharma')[6] and Arya Dharma are historical endonyms for Hinduism.[7]

Hinduism entails diverse systems of thought, marked by a range of shared concepts that discuss theology, mythology, and other topics in textual sources.[8] Hindu texts have been classified into Śruti (lit. 'heard') and Smṛti (lit. 'remembered'). The major Hindu scriptures are the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Puranas, the Mahabharata (including the Bhagavad Gita), the Ramayana, and the Agamas.[9][10] Prominent themes in Hindu beliefs include the karma (action, intent and consequences),[9][11] saṃsāra (the cycle of death and rebirth) and the four Puruṣārthas, proper goals or aims of human life, namely: dharma (ethics/duties), artha (prosperity/work), kama (desires/passions) and moksha (liberation/emancipation from passions and ultimately saṃsāra).[12][13][14] Hindu religious practices include devotion (bhakti), worship (puja), sacrificial rites (yajna), and meditation (dhyana) and yoga.[15] Hinduism has no central doctrinal authority and many Hindus do not claim to belong to any denomination.[16] However, scholarly studies notify four major denominations: Shaivism, Vaishnavism, Shaktism and Smartism, .[17][18] The six Āstika schools of Hindu philosophy that recognise the authority of the Vedas are: Sankhya, Yoga, Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Mīmāṃsā, and Vedanta.[19][20]

While the traditional Itihasa-Purana and its derived Epic-Puranic chronology present Hinduism as a tradition existing for thousands of years, scholars regard Hinduism as a fusion[note 5] or synthesis[note 6] of Brahmanical orthopraxy[note 7] with various Indian cultures,[note 8] having diverse roots[note 9] and no specific founder.[21] This Hindu synthesis emerged after the Vedic period, between c. 500[22] to 200[23] BCE, and c. 300 CE,[22] in the period of the second urbanisation and the early classical period of Hinduism when the epics and the first Purānas were composed.[22][23] It flourished in the medieval period, with the decline of Buddhism in India.[24] Since the 19th century, modern Hinduism, influenced by Western culture, has acquired a great appeal in the West, most notably reflected in the popularisation of Yoga and various sects such as Transcendental Meditation and the ISKCON's Hare Krishna movement.[25]

Hinduism is the world's third-largest religion, with approximately 1.20 billion followers, or around 15% of the global population, known as Hindus,[web 1][web 2] centered mainly in India,[26] Nepal, Mauritius, and in Bali, Indonesia.[27] Significant numbers of Hindu communities are found in the countries of South Asia, in Southeast Asia, in the Caribbean, Middle East, North America, Europe, Oceania and Africa.[28][29][30]

Etymology

[edit]The word Hindū is an exonym,[31] derived from Sanskrit word Sindhu,[32] the name of the Indus River as well as the country of the lower Indus basin (Sindh).[33][34][note 10] The Proto-Iranian sound change *s > h occurred between 850 and 600 BCE.[36] "Hindu" occurs in Avesta as heptahindu, equivalent to Rigvedic sapta sindhu.[37] The 6th-century BCE inscription of Darius I mentions Hindush (referring to Sindh) among his provinces.[38][39] Hindustan (spelt "hndstn") is found in a Sasanian inscription from the 3rd century CE.[37] The term Hindu in these ancient records is a geographical term and did not refer to a religion.[40] In Arabic texts, "Hind", a derivative of Persian "Hindu", was used to refer to the land beyond the Indus[41] and therefore, all the people in that land were "Hindus", according to historian Romila Thapar.[42] By the 13th century, Hindustan emerged as a popular alternative name of India.[43]

Among the earliest known records of 'Hindu' with connotations of religion may be in the 7th-century CE Chinese text Record of the Western Regions by Xuanzang.[38] In the 14th century, 'Hindu' appeared in several texts in Persian, Sanskrit and Prakrit within India, and subsequently in vernacular languages, often in comparative contexts to contrast them with Muslims or "Turks". Examples include the 14th-century Persian text Futuhu's-salatin by 'Abd al-Malik Isami,[note 2] Jain texts such as Vividha Tirtha Kalpa and Vidyatilaka,[44] circa 1400 Apabhramsa text Kīrttilatā by Vidyapati,[45] 16–18th century Bengali Gaudiya Vaishnava texts,[46] etc. These native usages of "Hindu" were borrowed from Persian, and they did not always have a religious connotation, but they often did.[47] In Indian texts, Hindu Dharma ("Hindu religion") was often used to refer to Hinduism.[46][48]

Starting in the 17th century, European merchants and colonists adopted "Hindu" (often with the English spelling "Hindoo") to refer to residents of India as a religious community.[49][note 11] The term got increasingly associated with the practices of Brahmins, who were also referred to as "Gentiles" and "Gentoos".[49] Terms such as "Hindoo faith" and "Hindoo religion" were often used, eventually leading to the appearance of "Hindooism" in a letter of Charles Grant in 1787, who used it along with "Hindu religion".[53] The first Indian to use "Hinduism" may have been Raja Ram Mohan Roy in 1816–17.[54] By the 1840s, the term "Hinduism" was used by those Indians who opposed British colonialism, and who wanted to distinguish themselves from Muslims and Christians.[55] Before the British began to categorise communities strictly by religion, Indians generally did not define themselves exclusively through their religious beliefs; instead identities were largely segmented on the basis of locality, language, varna, jāti, occupation, and sect.[56][note 12]

Definitions

[edit]"Hinduism" is an umbrella-term,[59] referring to a broad range of sometimes opposite and often competitive traditions.[60] In Western ethnography, the term refers to the fusion,[note 5] or synthesis,[note 6][61] of various Indian cultures and traditions,[62][note 8] with diverse roots[63][note 9] and no founder.[21] This Hindu synthesis emerged after the Vedic period, between c. 500[22]–200[23] BCE and c. 300 CE,[22] in the period of the Second Urbanisation and the early classical period of Hinduism, when the epics and the first Puranas were composed.[22][23] It flourished in the medieval period, with the decline of Buddhism in India.[24] Hinduism's variations in belief and its broad range of traditions make it difficult to define as a religion according to traditional Western conceptions.[64]

Hinduism includes a diversity of ideas on spirituality and traditions; Hindus can be polytheistic, pantheistic, panentheistic, pandeistic, henotheistic, monotheistic, monistic, agnostic, atheistic or humanist.[65][66] According to Mahatma Gandhi, "a man may not believe in God and still call himself a Hindu".[67] According to Wendy Doniger, "ideas about all the major issues of faith and lifestyle – vegetarianism, nonviolence, belief in rebirth, even caste – are subjects of debate, not dogma."[56]

Because of the wide range of traditions and ideas covered by the term Hinduism, arriving at a comprehensive definition is difficult.[40] The religion "defies our desire to define and categorize it".[68] Hinduism has been variously defined as a religion, a religious tradition, a set of religious beliefs, and "a way of life".[69][note 1] From a Western lexical standpoint, Hinduism, like other faiths, is appropriately referred to as a religion. In India, the term (Hindu) dharma is used, which is broader than the Western term "religion," and refers to the religious attitudes and behaviours, the 'right way to live', as preserved and transmitted in the various traditions collectively referred to as "Hinduism."[70][71][72][b]

The study of India and its cultures and religions, and the definition of "Hinduism", has been shaped by the interests of colonialism and by Western notions of religion.[73][74] Since the 1990s, those influences and its outcomes have been the topic of debate among scholars of Hinduism,[73][note 13] and have also been taken over by critics of the Western view on India.[75][note 14]

Typology

[edit]

Hinduism as it is commonly known can be subdivided into a number of major currents. Of the historical division into six darsanas (philosophies), two schools, Vedanta and Yoga, are currently the most prominent.[76] The six āstika schools of Hindu philosophy, which recognise the authority of the Vedas are: Sānkhya, Yoga, Nyāya, Vaisheshika, Mimāmsā, and Vedānta.[19][20]

Classified by primary deity or deities, four major Hinduism modern currents are Vaishnavism (God Vishnu), Shaivism (God Shiva), Shaktism (Goddess Adi Shakti) and Smartism (five deities treated as equals).[77][78][17][18] Hinduism also accepts numerous divine beings, with many Hindus considering the deities to be aspects or manifestations of a single impersonal absolute or ultimate reality or Supreme God, while some Hindus maintain that a specific deity represents the supreme and various deities are lower manifestations of this supreme.[79] Other notable characteristics include a belief in the existence of ātman (self), reincarnation of one's ātman, and karma as well as a belief in dharma (duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and right way of living), although variation exists, with some not following these beliefs.

June McDaniel (2007) classifies Hinduism into six major kinds and numerous minor kinds, in order to understand the expression of emotions among the Hindus.[80] The major kinds, according to McDaniel are Folk Hinduism, based on local traditions and cults of local deities and is the oldest, non-literate system; Vedic Hinduism based on the earliest layers of the Vedas, traceable to the 2nd millennium BCE; Vedantic Hinduism based on the philosophy of the Upanishads, including Advaita Vedanta, emphasising knowledge and wisdom; Yogic Hinduism, following the text of Yoga Sutras of Patanjali emphasising introspective awareness; Dharmic Hinduism or "daily morality", which McDaniel states is stereotyped in some books as the "only form of Hindu religion with a belief in karma, cows and caste"; and bhakti or devotional Hinduism, where intense emotions are elaborately incorporated in the pursuit of the spiritual.[80]

Michaels distinguishes three Hindu religions and four forms of Hindu religiosity.[81] The three Hindu religions are "Brahmanic-Sanskritic Hinduism", "folk religions and tribal religions", and "founded religions".[82] The four forms of Hindu religiosity are the classical "karma-marga",[83] jnana-marga,[84] bhakti-marga,[84] and "heroism", which is rooted in militaristic traditions. These militaristic traditions include Ramaism (the worship of a hero of epic literature, Rama, believing him to be an incarnation of Vishnu)[85] and parts of political Hinduism.[83] "Heroism" is also called virya-marga.[84] According to Michaels, one out of nine Hindu belongs by birth to one or both of the Brahmanic-Sanskritic Hinduism and Folk religion typology, whether practising or non-practicing. He classifies most Hindus as belonging by choice to one of the "founded religions" such as Vaishnavism and Shaivism that are moksha-focussed and often de-emphasise Brahman (Brahmin) priestly authority yet incorporate ritual grammar of Brahmanic-Sanskritic Hinduism.[86] He includes among "founded religions" Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism that are now distinct religions, syncretic movements such as Brahmo Samaj and the Theosophical Society, as well as various "Guru-isms" and new religious movements such as Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, BAPS and ISKCON.[87]

Inden states that the attempt to classify Hinduism by typology started in the imperial times, when proselytising missionaries and colonial officials sought to understand and portray Hinduism from their interests.[88] Hinduism was construed as emanating not from a reason of spirit but fantasy and creative imagination, not conceptual but symbolical, not ethical but emotive, not rational or spiritual but of cognitive mysticism. This stereotype followed and fit, states Inden, with the imperial imperatives of the era, providing the moral justification for the colonial project.[88] From tribal Animism to Buddhism, everything was subsumed as part of Hinduism. The early reports set the tradition and scholarly premises for the typology of Hinduism, as well as the major assumptions and flawed presuppositions that have been at the foundation of Indology. Hinduism, according to Inden, has been neither what imperial religionists stereotyped it to be, nor is it appropriate to equate Hinduism to be merely the monist pantheism and philosophical idealism of Advaita Vedanta.[88]

Some academics suggest that Hinduism can be seen as a category with "fuzzy edges" rather than as a well-defined and rigid entity. Some forms of religious expression are central to Hinduism and others, while not as central, still remain within the category. Based on this idea Gabriella Eichinger Ferro-Luzzi has developed a 'Prototype Theory approach' to the definition of Hinduism.[89]

Sanātana Dharma

[edit]

To its adherents, Hinduism is a traditional way of life.[93] Many practitioners refer to the "orthodox" form of Hinduism as Sanātana Dharma, "the eternal law" or the "eternal way".[94][95] Hindus regard Hinduism to be thousands of years old. The Puranic chronology, as narrated in the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and the Puranas, envisions a timeline of events related to Hinduism starting well before 3000 BCE. The word dharma is used here to mean religion similar to modern Indo-Aryan languages, rather than with its original Sanskrit meaning. All aspects of a Hindu life, namely acquiring wealth (artha), fulfilment of desires (kama), and attaining liberation (moksha), are viewed here as part of "dharma", which encapsulates the "right way of living" and eternal harmonious principles in their fulfilment.[96][97] The use of the term Sanātana Dharma for Hinduism is a modern usage, based on the belief that the origins of Hinduism lie beyond human history, as revealed in the Hindu texts.[98][99][100][101][clarification needed]

Sanātana Dharma refers to "timeless, eternal set of truths" and this is how Hindus view the origins of their religion. It is viewed as those eternal truths and traditions with origins beyond human history– truths divinely revealed (Shruti) in the Vedas, the most ancient of the world's scriptures.[102][103] To many Hindus, Hinduism is a tradition that can be traced at least to the ancient Vedic era. The Western term "religion" to the extent it means "dogma and an institution traceable to a single founder" is inappropriate for their tradition, states Hatcher.[102][104][note 15]

Sanātana Dharma historically referred to the "eternal" duties religiously ordained in Hinduism, duties such as honesty, refraining from injuring living beings (ahiṃsā), purity, goodwill, mercy, patience, forbearance, self-restraint, generosity, and asceticism. These duties applied regardless of a Hindu's class, caste, or sect, and they contrasted with svadharma, one's "own duty", in accordance with one's class or caste (varṇa) and stage in life (puruṣārtha).[web 3] In recent years, the term has been used by Hindu leaders, reformers, and nationalists to refer to Hinduism. Sanatana dharma has become a synonym for the "eternal" truth and teachings of Hinduism, that transcend history and are "unchanging, indivisible and ultimately nonsectarian".[web 3]

Vaidika dharma

[edit]Some have referred to Hinduism as the Vaidika dharma,[106] bypassing the Tanttric revelations. The word 'Vaidika' in Sanskrit means 'derived from or conformable to the Veda' or 'relating to the Veda'.[web 4] Traditional scholars employed the terms Vaidika and Avaidika, those who accept the Vedas as a source of authoritative knowledge and those who do not, to differentiate various Indian schools from Jainism, Buddhism and Charvaka. According to Klaus Klostermaier, the term Vaidika dharma is the earliest self-designation of Hinduism.[107][108] According to Arvind Sharma, the historical evidence suggests that "the Hindus were referring to their religion by the term vaidika dharma or a variant thereof" by the 4th-century CE.[109] According to Brian K. Smith, "[i]t is 'debatable at the very least' as to whether the term Vaidika Dharma cannot, with the proper concessions to historical, cultural, and ideological specificity, be comparable to and translated as 'Hinduism' or 'Hindu religion'."[110]

Whatever the case, many Hindu religious sources see persons or groups which they consider as non-Vedic (and which reject Vedic varṇāśrama – 'caste and life stage' orthodoxy) as being heretics (pāṣaṇḍa/pākhaṇḍa). For example, the Bhāgavata Purāṇa considers Buddhists, Jains as well as some Shaiva groups like the Paśupatas and Kāpālins to be pāṣaṇḍas (heretics).[111]

According to Alexis Sanderson, the early Sanskrit texts differentiate between Vaidika, Vaishnava, Shaiva, Shakta, Saura, Buddhist and Jaina traditions. However, the late 1st-millennium CE Indic consensus had "indeed come to conceptualize a complex entity corresponding to Hinduism as opposed to Buddhism and Jainism excluding only certain forms of antinomian Shakta-Shaiva" from its fold.[web 5] Some in the Mimamsa school of Hindu philosophy considered the Agamas such as the Pancaratrika to be invalid because it did not conform to the Vedas. Some Kashmiri scholars rejected the esoteric tantric traditions to be a part of Vaidika dharma.[web 5][web 6] The Atimarga Shaivism ascetic tradition, datable to about 500 CE, challenged the Vaidika frame and insisted that their Agamas and practices were not only valid, they were superior than those of the Vaidikas.[web 7] However, adds Sanderson, this Shaiva ascetic tradition viewed themselves as being genuinely true to the Vedic tradition and "held unanimously that the Śruti and Smṛti of Brahmanism are universally and uniquely valid in their own sphere, [...] and that as such they [Vedas] are man's sole means of valid knowledge [...]".[web 7]

The term Vaidika dharma means a code of practice that is "based on the Vedas", but it is unclear what "based on the Vedas" really implies, states Julius Lipner.[104] The Vaidika dharma or "Vedic way of life", states Lipner, does not mean "Hinduism is necessarily religious" or that Hindus have a universally accepted "conventional or institutional meaning" for that term.[104] To many, it is as much a cultural term. Many Hindus do not have a copy of the Vedas nor have they ever seen or personally read parts of a Veda, like a Christian, might relate to the Bible or a Muslim might to the Quran. Yet, states Lipner, "this does not mean that their [Hindus] whole life's orientation cannot be traced to the Vedas or that it does not in some way derive from it".[104]

Though many religious Hindus implicitly acknowledge the authority of the Vedas, this acknowledgment is often "no more than a declaration that someone considers himself [or herself] a Hindu,"[112][note 16] and "most Indians today pay lip service to the Veda and have no regard for the contents of the text."[113] Some Hindus challenge the authority of the Vedas, thereby implicitly acknowledging its importance to the history of Hinduism, states Lipner.[104]

Legal definition

[edit]Bal Gangadhar Tilak gave the following definition in Gita Rahasya (1915): "Acceptance of the Vedas with reverence; recognition of the fact that the means or ways to salvation are diverse; and realization of the truth that the number of gods to be worshipped is large".[114][115] It was quoted by the Indian Supreme Court in 1966,[114][115] and again in 1995, "as an 'adequate and satisfactory definition,"[116] and is still the legal definition of a Hindu today.[117]

Diversity and unity

[edit]

Diversity

[edit]Hindu beliefs are vast and diverse, and thus Hinduism is often referred to as a "family of religions" rather than a single religion.[web 8] Within each tradition in Hinduism, there are different theologies, practices, and sacred texts, often including unique interpretations, commentaries, and derivative works that build upon shared foundational scriptures.[118][119][120] Hinduism does not have a "unified system of belief encoded in a declaration of faith or a creed",[40] but is rather an umbrella term comprising the plurality of religious phenomena of India.[a][121] According to the Supreme Court of India,

Unlike other religions in the World, the Hindu religion does not claim any one Prophet, it does not worship any one God, it does not believe in any one philosophic concept, it does not follow any one act of religious rites or performances; in fact, it does not satisfy the traditional features of a religion or creed. It is a way of life and nothing more".[122]

Part of the problem with a single definition of the term Hinduism is the fact that Hinduism does not have a founder.[123] It is a synthesis of various traditions,[124] the "Brahmanical orthopraxy, the renouncer traditions and popular or local traditions".[125]

Theism is also difficult to use as a unifying doctrine for Hinduism, because while some Hindu philosophies postulate a theistic ontology of creation, other Hindus are or have been atheists.[126]

Sense of unity

[edit]Despite the differences, there is also a sense of unity.[127] Most Hindu traditions revere a body of religious or sacred literature, the Vedas,[128] although there are exceptions.[129] These texts are a reminder of the ancient cultural heritage and point of pride for Hindus,[130][131] though Louis Renou stated that "even in the most orthodox domains, the reverence to the Vedas has come to be a simple raising of the hat".[130][132]

Halbfass states that, although Shaivism and Vaishnavism may be regarded as "self-contained religious constellations",[127] there is a degree of interaction and reference between the "theoreticians and literary representatives"[127] of each tradition that indicates the presence of "a wider sense of identity, a sense of coherence in a shared context and of inclusion in a common framework and horizon".[127]

Classical Hinduism

[edit]Brahmins played an essential role in the development of the post-Vedic Hindu synthesis, disseminating Vedic culture to local communities, and integrating local religiosity into the trans-regional Brahmanic culture.[133] In the post-Gupta period Vedanta developed in southern India, where orthodox Brahmanic culture and the Hindu culture were preserved,[134] building on ancient Vedic traditions while "accommoda[ting] the multiple demands of Hinduism."[135]

Medieval developments

[edit]The notion of common denominators for several religions and traditions of India further developed from the 12th century CE.[136] Lorenzen traces the emergence of a "family resemblance", and what he calls as "beginnings of medieval and modern Hinduism" taking shape, at c. 300–600 CE, with the development of the early Puranas, and continuities with the earlier Vedic religion.[137] Lorenzen states that the establishment of a Hindu self-identity took place "through a process of mutual self-definition with a contrasting Muslim Other".[138] According to Lorenzen, this "presence of the Other"[138] is necessary to recognise the "loose family resemblance" among the various traditions and schools.[139]

According to the Indologist Alexis Sanderson, before Islam arrived in India, the "Sanskrit sources differentiated Vaidika, Vaiṣṇava, Śaiva, Śākta, Saura, Buddhist, and Jaina traditions, but they had no name that denotes the first five of these as a collective entity over and against Buddhism and Jainism". This absence of a formal name, states Sanderson, does not mean that the corresponding concept of Hinduism did not exist. By late 1st-millennium CE, the concept of a belief and tradition distinct from Buddhism and Jainism had emerged.[web 5] This complex tradition accepted in its identity almost all of what is currently Hinduism, except certain antinomian tantric movements.[web 5] Some conservative thinkers of those times questioned whether certain Shaiva, Vaishnava and Shakta texts or practices were consistent with the Vedas, or were invalid in their entirety. Moderates then, and most orthoprax scholars later, agreed that though there are some variations, the foundation of their beliefs, the ritual grammar, the spiritual premises, and the soteriologies were the same. "This sense of greater unity", states Sanderson, "came to be called Hinduism".[web 5]

According to Nicholson, already between the 12th and the 16th centuries "certain thinkers began to treat as a single whole the diverse philosophical teachings of the Upanishads, epics, Puranas, and the schools known retrospectively as the 'six systems' (saddarsana) of mainstream Hindu philosophy."[140] The tendency of "a blurring of philosophical distinctions" has also been noted by Mikel Burley.[141] Hacker called this "inclusivism"[128] and Michaels speaks of "the identificatory habit".[8] Lorenzen locates the origins of a distinct Hindu identity in the interaction between Muslims and Hindus,[142] and a process of "mutual self-definition with a contrasting Muslim other",[143][38] which started well before 1800.[144] Michaels notes:

As a counteraction to Islamic supremacy and as part of the continuing process of regionalization, two religious innovations developed in the Hindu religions: the formation of sects and a historicization which preceded later nationalism ... [S]aints and sometimes militant sect leaders, such as the Marathi poet Tukaram (1609–1649) and Ramdas (1608–1681), articulated ideas in which they glorified Hinduism and the past. The Brahmins also produced increasingly historical texts, especially eulogies and chronicles of sacred sites (Mahatmyas), or developed a reflexive passion for collecting and compiling extensive collections of quotations on various subjects.[145]

Colonial views

[edit]The notion and reports on "Hinduism" as a "single world religious tradition"[146] were also popularised by 19th-century proselytising missionaries and European Indologists, roles sometimes served by the same person, who relied on texts preserved by Brahmins (priests) for their information of Indian religions, and animist observations that the missionary Orientalists presumed was Hinduism.[146][88][147] These reports influenced perceptions about Hinduism. Scholars such as Pennington state that the colonial polemical reports led to fabricated stereotypes where Hinduism was mere mystic paganism devoted to the service of devils,[note 17] while other scholars state that the colonial constructions influenced the belief that the Vedas, Bhagavad Gita, Manusmriti and such texts were the essence of Hindu religiosity, and in the modern association of 'Hindu doctrine' with the schools of Vedanta (in particular Advaita Vedanta) as a paradigmatic example of Hinduism's mystical nature".[149][note 18] Pennington, while concurring that the study of Hinduism as a world religion began in the colonial era, disagrees that Hinduism is a colonial European era invention.[150] He states that the shared theology, common ritual grammar and way of life of those who identify themselves as Hindus is traceable to ancient times.[150][note 19]

Hindu modernism and neo-Vedanta

[edit]

All of religion is contained in the Vedanta, that is, in the three stages of the Vedanta philosophy, the Dvaita, Vishishtâdvaita and Advaita; one comes after the other. These are the three stages of spiritual growth in man. Each one is necessary. This is the essential of religion: the Vedanta, applied to the various ethnic customs and creeds of India, is Hinduism.

This inclusivism[159] was further developed in the 19th and 20th centuries by Hindu reform movements and Neo-Vedanta,[160] and has become characteristic of modern Hinduism.[128]

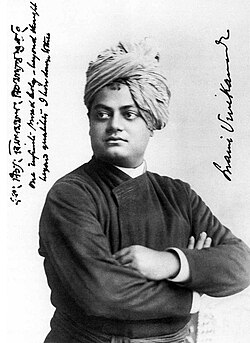

Beginning in the 19th century, Indian modernists re-asserted Hinduism as a major asset of Indian civilisation,[74] meanwhile "purifying" Hinduism from its Tantric elements[161] and elevating the Vedic elements. Western stereotypes were reversed, emphasising the universal aspects, and introducing modern approaches of social problems.[74] This approach had great appeal, not only in India, but also in the west.[74] Major representatives of "Hindu modernism"[162] are Ram Mohan Roy, Swami Vivekananda, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Mahatma Gandhi.[163]

Raja Rammohan Roy is known as the father of the Hindu Renaissance.[164] He was a major influence on Swami Vivekananda, who, according to Flood, was "a figure of great importance in the development of a modern Hindu self-understanding and in formulating the West's view of Hinduism".[165] Central to his philosophy is the idea that the divine exists in all beings, that all human beings can achieve union with this "innate divinity",[162] and that seeing this divine as the essence of others will further love and social harmony.[162] According to Vivekananda, there is an essential unity to Hinduism, which underlies the diversity of its many forms.[162] According to Flood, Vivekananda's vision of Hinduism "is one generally accepted by most English-speaking middle-class Hindus today".[166] Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan sought to reconcile western rationalism with Hinduism, "presenting Hinduism as an essentially rationalistic and humanistic religious experience".[167]

This "Global Hinduism"[168] has a worldwide appeal, transcending national boundaries[168] and, according to Flood, "becoming a world religion alongside Christianity, Islam and Buddhism",[168] both for the Hindu diaspora communities and for westerners who are attracted to non-western cultures and religions.[168] It emphasises universal spiritual values such as social justice, peace and "the spiritual transformation of humanity".[168] It has developed partly due to "re-enculturation",[169] or the pizza effect,[169] in which elements of Hindu culture have been exported to the West, gaining popularity there, and as a consequence also gained greater popularity in India.[169] This globalisation of Hindu culture brought "to the West teachings which have become an important cultural force in western societies, and which in turn have become an important cultural force in India, their place of origin".[170]

Modern India and the world

[edit]

The Hindutva movement has extensively argued for the unity of Hinduism, dismissing the differences and regarding India as a Hindu-country since ancient times.[171] And there are assumptions of political dominance of Hindu nationalism in India, also known as 'Neo-Hindutva'.[172][173] There have also been increase in pre-dominance of Hindutva in Nepal, similar to that of India.[174] The scope of Hinduism is also increasing in the other parts of the world, due to the cultural influences such as Yoga and Hare Krishna movement by many missionaries organisations, especially by ISKCON and this is also due to the migration of Indian Hindus to the other nations of the world.[175][176] Hinduism is growing fast in many western nations and in some African nations.[note 20]

Main traditions

[edit]Denominations

[edit]

Hinduism has no central doctrinal authority and many practising Hindus do not claim to belong to any particular denomination or tradition.[16] Four major denominations are, however, used in scholarly studies: Shaivism, Shaktism, Smartism, and Vaishnavism.[77][78][17][18] These denominations differ primarily in the central deity worshipped, the traditions and the soteriological outlook.[179] The denominations of Hinduism, states Lipner, are unlike those found in major religions of the world, because Hindu denominations are fuzzy with individuals practising more than one, and he suggests the term "Hindu polycentrism".[180]

There are no census data available on demographic history or trends for the traditions within Hinduism.[181] Estimates vary on the relative number of adherents in the different traditions of Hinduism. According to a 2020 estimate by The World Religion Database (WRD), hosted at Boston University's Institute on Culture, Religion and World Affairs (CURA), the Vaishnavism tradition is the largest group with about 399 million Hindus, followed by Shaivism with 385 million Hindus, Shaktism with 305 million Hindus and other traditions including Neo-Hinduism and Reform Hinduism with 25 million Hindus.[182] In contrast, according to Jones and Ryan, Shaivism is the largest tradition of Hinduism.[183][note 21]

Vaishnavism is the devotional religious tradition that worships Vishnu[note 22] and his avatars, particularly Krishna and Rama.[185] The adherents of this sect are generally non-ascetic, monastic, oriented towards community events and devotionalism practices inspired by "intimate loving, joyous, playful" Krishna and other Vishnu avatars.[179] These practices sometimes include community dancing, singing of Kirtans and Bhajans, with sound and music believed by some to have meditative and spiritual powers.[186] Temple worship and festivals are typically elaborate in Vaishnavism.[187] The Bhagavad Gita and the Ramayana, along with Vishnu-oriented Puranas provide its theistic foundations.[188]

Shaivism is the tradition that focuses on Shiva. Shaivas are more attracted to ascetic individualism, and it has several sub-schools.[179] Their practices include bhakti-style devotionalism, yet their beliefs lean towards nondual, monistic schools of Hinduism such as Advaita and Raja Yoga.[189][186] Some Shaivas worship in temples, while others emphasise yoga, striving to be one with Shiva within.[190] Avatars are uncommon, and some Shaivas visualise god as half male, half female, as a fusion of the male and female principles (Ardhanarishvara). Shaivism is related to Shaktism, wherein Shakti is seen as spouse of Shiva.[189] Community celebrations include festivals, and participation, with Vaishnavas, in pilgrimages such as the Kumbh Mela.[191] Shaivism has been more commonly practised in the Himalayan north from Kashmir to Nepal, and in south India.[192]

Shaktism focuses on goddess worship of Shakti or Devi as cosmic mother,[179] and it is particularly common in northeastern and eastern states of India such as Assam and Bengal. Devi is depicted as in gentler forms like Parvati, the consort of Shiva; or, as fierce warrior goddesses like Kali and Durga. Followers of Shaktism recognise Shakti as the power that underlies the male principle. Shaktism is also associated with Tantra practices.[193] Community celebrations include festivals, some of which include processions and idol immersion into sea or other water bodies.[194]

Smartism centers its worship simultaneously on all the major Hindu deities: Shiva, Vishnu, Shakti, Ganesha, Surya and Skanda.[195] The Smarta tradition developed during the (early) Classical Period of Hinduism around the beginning of the Common Era, when Hinduism emerged from the interaction between Brahmanism and local traditions.[196][197] The Smarta tradition is aligned with Advaita Vedanta, and regards Adi Shankara as its founder or reformer, who considered worship of God-with-attributes (Saguna Brahman) as a journey towards ultimately realising God-without-attributes (nirguna Brahman, Atman, Self-knowledge).[198][199] The term Smartism is derived from Smriti texts of Hinduism, meaning those who remember the traditions in the texts.[189][200] This Hindu sect practices a philosophical Jnana yoga, scriptural studies, reflection, meditative path seeking an understanding of Self's oneness with God.[189][201]

Ethnicities

[edit]

Hinduism is traditionally a multi- or polyethnic religion. On the Indian subcontinent, it is widespread among many Indo-Aryan, Dravidian and other South Asian ethnic groups,[202] for example, the Meitei people (Tibeto-Burman ethnicity in the northeastern Indian state Manipur).[203]

In addition, in antiquity and the Middle Ages, Hinduism was the state religion in many Indianized kingdoms of Asia, the Greater India – from Afghanistan (Kabul) in the West and including almost all of Southeast Asia in the East (Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, partly Philippines) – and only by the 15th century was nearly everywhere supplanted by Buddhism and Islam,[204][205] except several still Hindu minor Austronesian ethnic groups, such as the Balinese[27] and Tenggerese people[206] in Indonesia, and the Chams in Vietnam.[207] Also, a small community of the Afghan Pashtuns who migrated to India after partition remain committed to Hinduism.[208]

The Indo-Aryan Kalash people in Pakistan traditionally practice an indigenous religion which is closely related to ancient Indo-Iranian religion, and resembles the ancient Vedic religion.[209] While it has been related to Greek religion, due to an origin-narrative which says that the Kalash descend from Alexander the Great's Greek soldiers, the Kalash speak an Indo-Aryan language, and their religion is closer to Hinduism than to the religion of Alexander's army.[210]

There are many new ethnic Ghanaian Hindus in Ghana, who have converted to Hinduism due to the works of Swami Ghanananda Saraswati and Hindu Monastery of Africa[211] From the beginning of the 20th century, by the forces of Baba Premananda Bharati (1858–1914), Swami Vivekananda, A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada and other missionaries, Hinduism gained a certain distribution among the Western peoples.[212]

Scriptures

[edit]

The ancient scriptures of Hinduism are initially in Vedic Sanskrit and later in classical Sanskrit. These texts are classified into two: Shruti and Smriti. Shruti is apauruṣeyā, (lit. 'not made of a man') but revealed by the rishis (lit. 'seers'), and regarded as having the highest authority, while the smriti are manmade and have secondary authority.[213] They are the two highest sources of dharma, the other two being Śiṣṭa Āchāra/Sadāchara (lit. 'conduct of noble people') and finally Ātma tuṣṭi (lit. 'what is pleasing to oneself').[note 24]

Hindu scriptures were composed, memorised and transmitted verbally, across generations, for many centuries before they were written down.[214][215]

Shruti (lit. 'that which is heard')[216] primarily refers to the Vedas, which form the earliest record of the Hindu scriptures, and are regarded as eternal truths revealed to the ancient sages (rishis).[217] There are four Vedas – Rigveda, Samaveda, Yajurveda and Atharvaveda. Each Veda has been subclassified into four major text types – the Samhitas (mantras and benedictions), the Aranyakas (text on rituals, ceremonies, sacrifices and symbolic-sacrifices), the Brahmanas (commentaries on rituals, ceremonies and sacrifices), and the Upanishads (text discussing meditation, philosophy and spiritual knowledge).[218][219][220][221] The first two parts of the Vedas were subsequently called the Karmakāṇḍa (ritualistic portion), while the last two form the Jñānakāṇḍa (knowledge portion, discussing spiritual insight and philosophical teachings).[222][223][224][225]

The Upanishads are the foundation of Hindu philosophical thought and have profoundly influenced diverse traditions.[226][227][155] Of the Shrutis (Vedic corpus), the Upanishads alone are widely influential among Hindus, considered scriptures par excellence of Hinduism, and their central ideas have continued to influence its thoughts and traditions.[226][153] Indian philosopher Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan states that the Upanishads have played a dominating role ever since their appearance.[228] There are 108 Muktikā Upanishads in Hinduism, of which between 10 and 13 are variously counted by scholars as Principal Upanishads.[225][229]

The most notable of the Smritis (lit. 'that which is remembered') are the Hindu epics and the Puranas (lit. 'that which is ancient'). The epics consist of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. The Bhagavad Gita is an integral part of the Mahabharata and one of the most popular sacred texts of Hinduism.[230] It is sometimes called Gitopanishad, then placed in the Shruti ("heard") category, being Upanishadic in content.[231] The Puranas, which started to be composed of c. 300 CE onward,[232] contain extensive mythologies, and are central in the distribution of common themes of Hinduism through vivid narratives. The Yoga Sutras is a classical text for the Hindu Yoga tradition, which gained renewed popularity in the 20th century.[233]

Since the 19th century, Indian modernists have re-asserted the 'Aryan origins' of Hinduism, "purifying" Hinduism from its Tantric elements[161] and elevating the Vedic elements. Hindu modernists like Vivekananda see the Vedas as the laws of the spiritual world, which would still exist even if they were not revealed to the sages.[234][235]

Tantra are the religious scriptures that give prominence to the female energy of the deity that in her personified form has both gentle and fierce form. In Tantric tradition, Radha, Parvati, Durga, and Kali are worshipped symbolically as well as in their personified forms.[236] The Agamas in Tantra refer to authoritative scriptures or the teachings of Shiva to Shakti,[237] while Nigamas refers to the Vedas and the teachings of Shakti to Shiva.[237] In Agamic schools of Hinduism, the Vedic literature and the Agamas are equally authoritative.[238][239]

Beliefs

[edit]

Prominent themes in Hindu beliefs include (but are not restricted to) Dharma (ethics/duties), Saṃsāra (the continuing cycle of entanglement in passions and the resulting birth, life, death, and rebirth), Karma (action, intent, and consequences), moksha (liberation from attachment and saṃsāra), and the various yogas (paths or practices).[11] However, not all of these themes are found among the various different systems of Hindu beliefs. Beliefs in moksha or saṃsāra are absent in certain Hindu beliefs, and were also absent among early forms of Hinduism, which was characterised by a belief in an Afterlife, with traces of this still being found among various Hindu beliefs, such as Śrāddha. Ancestor worship once formed an integral part of Hindu beliefs and is today still found as an important element in various Folk Hindu streams.[240][241][242][243][244][245][246]

Purusharthas

[edit]Purusharthas refers to the objectives of human life. Classical Hindu thought accepts four proper goals or aims of human life, known as Puruṣārthas – Dharma, Artha, Kama and Moksha.[247][248]

Dharma (moral duties, righteousness, ethics)

[edit]Dharma is considered the foremost goal of a human being in Hinduism.[249] The concept of dharma includes behaviours that are considered to be in accord with rta, the order that makes life and universe possible,[250] and includes duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and "right way of living".[251] Hindu dharma includes the religious duties, moral rights and duties of each individual, as well as behaviours that enable social order, right conduct, and those that are virtuous.[251] Dharma is that which all existing beings must accept and respect to sustain harmony and order in the world. It is the pursuit and execution of one's nature and true calling, thus playing one's role in cosmic concert.[252] The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad states it as:

Nothing is higher than Dharma. The weak overcomes the stronger by Dharma, as over a king. Truly that Dharma is the Truth (Satya); Therefore, when a man speaks the Truth, they say, "He speaks the Dharma"; and if he speaks Dharma, they say, "He speaks the Truth!" For both are one.

— Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 1.4.xiv[253][254]

In the Mahabharata, Krishna defines dharma as upholding both this-worldly and other-worldly affairs. (Mbh 12.110.11). The word Sanātana means eternal, perennial, or forever; thus, Sanātana Dharma signifies that it is the dharma that has neither beginning nor end.[255]

Artha (the means or resources needed for a fulfilling life)

[edit]Artha is the virtuous pursuit of means, resources, assets, or livelihood, for the purpose of meeting obligations, economic prosperity, and to have a fulfilling life. It is inclusive of political life, diplomacy, and material well-being. The artha concept includes all "means of life", activities and resources that enables one to be in a state one wants to be in, wealth, career and financial security.[13] The proper pursuit of artha is considered an important aim of human life in Hinduism.[256][257]

A central premise of Hindu philosophy is that every person should live a joyous, pleasurable and fulfilling life, where every person's needs are acknowledged and fulfilled. A person's needs can only be fulfilled when sufficient means are available. Artha, then, is best described as the pursuit of the means necessary for a joyous, pleasurable and fulfilling life.[258]

Kāma (sensory, emotional and aesthetic pleasure)

[edit]Kāma (Sanskrit, Pali: काम) means desire, wish, passion, longing, and pleasure of the senses, the aesthetic enjoyment of life, affection and love, with or without sexual connotations.[259][260]

In contemporary Indian literature kama is often used to refer to sexual desire, but in ancient Indian literature kāma is expansive and includes any kind of enjoyment and pleasure, such as pleasure deriving from the arts. The ancient Indian Epic the Mahabharata describes kama as any agreeable and desirable experience generated by the interaction of one or more of the five senses with anything associated with that sense, when in harmony with the other goals of human life (dharma, artha and moksha).[261]

In Hinduism, kama is considered an essential and healthy goal of human life when pursued without sacrificing dharma, artha and moksha.[262]

Mokṣa (liberation, freedom from suffering)

[edit]Moksha (Sanskrit: मोक्ष, romanized: mokṣa) or mukti (Sanskrit: मुक्ति) is the ultimate, most important goal in Hinduism. Moksha is a concept associated with liberation from sorrow, suffering, and for many theistic schools of Hinduism, liberation from samsara (a birth-rebirth cycle). A release from this eschatological cycle in the afterlife is called moksha in theistic schools of Hinduism.[252][263][264]

Due to the belief in Hinduism that the Atman is eternal, and the concept of Purusha (the cosmic self or cosmic consciousness),[265] death can be seen as insignificant in comparison to the eternal Atman or Purusha.[266]

Differing views on the nature of moksha

[edit]The meaning of moksha differs among the various Hindu schools of thought.

Advaita Vedanta holds that upon attaining moksha a person knows their essence, or self, to be pure consciousness or the witness-consciousness and identifies it as identical to Brahman.[267][268]

More generally, in the theistic schools of Hinduism moksha is usually seen as liberation from saṃsāra, while for other schools, such as the monistic school, moksha happens during a person's lifetime and is a psychological concept.[269][267][270][271][268]

According to Deutsch, moksha is a transcendental consciousness of the perfect state of being, of self-realization, of freedom, and of "realizing the whole universe as the Self".[269][267][271] Moksha when viewed as a psychological concept, suggests Klaus Klostermaier,[268] implies a setting free of hitherto fettered faculties, a removing of obstacles to an unrestricted life, permitting a person to be more truly a person in the fullest sense. This concept presumes an unused human potential of creativity, compassion and understanding which had been previously blocked and shut out.[268]

Due to these different views on the nature of moksha, the Vedantic school separates this into two views – Jivanmukti (liberation in this life) and Videhamukti (liberation after death).[268][272][273]

Karma and saṃsāra

[edit]Karma translates literally as action, work, or deed,[274] and also refers to a Vedic theory of "moral law of cause and effect".[275][276] The theory is a combination of (1) causality that may be ethical or non-ethical; (2) ethicisation, that is good or bad actions have consequences; and (3) rebirth.[277] Karma theory is interpreted as explaining the present circumstances of an individual with reference to their actions in the past. These actions and their consequences may be in a person's current life, or, according to some schools of Hinduism, in past lives.[277][278] This cycle of birth, life, death and rebirth is called saṃsāra. Liberation from saṃsāra through moksha is believed to ensure lasting happiness and peace.[279][280] Hindu scriptures teach that the future is both a function of current human effort derived from free will and past human actions that set the circumstances.[281] The idea of reincarnation, or saṃsāra, is not mentioned in the early layers of historical Hindu texts such as the Rigveda.[282][283] The later layers of the Rigveda do mention ideas that suggest an approach towards the idea of rebirth, according to Ranade.[284][285] According to Sayers, these earliest layers of Hindu literature show ancestor worship and rites such as sraddha (offering food to the ancestors). The later Vedic texts such as the Aranyakas and the Upanisads show a different soteriology based on reincarnation, they show little concern with ancestor rites, and they begin to philosophically interpret the earlier rituals.[286][287][288] The idea of reincarnation and karma have roots in the Upanishads of the late Vedic period, predating the Buddha and the Mahavira.[289][290]

Concept of God

[edit]Hinduism is a diverse system of thought with a wide variety of beliefs[65][291][web 11] its concept of God is complex and depends upon each individual and the tradition and philosophy followed. It is sometimes referred to as henotheistic (i.e., involving devotion to a single god while accepting the existence of others), but any such term is an overgeneralisation.[292][293]

Who really knows?

Who will here proclaim it?

Whence was it produced? Whence is this creation?

The gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe.

Who then knows whence it has arisen?

— Nasadiya Sukta, concerns the origin of the universe, Rigveda, 10:129–6[294][295][296]

The Nasadiya Sukta (Creation Hymn) of the Rig Veda is one of the earliest texts[297] which "demonstrates a sense of metaphysical speculation" about what created the universe, the concept of god(s) and The One, and whether even The One knows how the universe came into being.[298][299] The Rig Veda praises various deities, none superior nor inferior, in a henotheistic manner.[300] The hymns repeatedly refer to One Truth and One Ultimate Reality. The "One Truth" of Vedic literature, in modern era scholarship, has been interpreted as monotheism, monism, as well as a deified Hidden Principles behind the great happenings and processes of nature.[301]

Hindus believe that all living creatures have a Self. This true "Self" of every person, is called the ātman. The Self is believed to be eternal.[302] According to the monistic/pantheistic (non-dualist) theologies of Hinduism (such as Advaita Vedanta school), this Atman is indistinct from Brahman, the supreme spirit or the Ultimate Reality.[303] The goal of life, according to the Advaita school, is to realise that one's Self is identical to supreme Self, that the supreme Self is present in everything and everyone, all life is interconnected and there is oneness in all life.[304][305][306] Dualistic schools (Dvaita and Bhakti) understand Brahman as a Supreme Being separate from individual Selfs.[307] They worship the Supreme Being variously as Vishnu, Brahma, Shiva, or Shakti, depending upon the sect. God is called Ishvara, Bhagavan, Parameshwara, Deva or Devi, and these terms have different meanings in different schools of Hinduism.[308][309][310]

Hindu texts accept a polytheistic framework, but this is generally conceptualised as the divine essence or luminosity that gives vitality and animation to the inanimate natural substances.[311] There is a divine in everything, human beings, animals, trees and rivers. It is observable in offerings to rivers, trees, tools of one's work, animals and birds, rising sun, friends and guests, teachers and parents.[311][312][313] It is the divine in these that makes each sacred and worthy of reverence, rather than them being sacred in and of themselves. This perception of divinity manifested in all things, as Buttimer and Wallin view it, makes the Vedic foundations of Hinduism quite distinct from animism, in which all things are themselves divine.[311] The animistic premise sees multiplicity, and therefore an equality of ability to compete for power when it comes to man and man, man and animal, man and nature, etc. The Vedic view does not perceive this competition, equality of man to nature, or multiplicity so much as an overwhelming and interconnecting single divinity that unifies everyone and everything.[311][314][315]

The Hindu scriptures name celestial entities called Devas (or Devi in feminine form), which may be translated into English as gods or heavenly beings.[note 25] The devas are an integral part of Hindu culture and are depicted in art, architecture and through icons, and stories about them are related in the scriptures, particularly in Indian epic poetry and the Puranas. They are, however, often distinguished from Ishvara, a personal god, with many Hindus worshipping Ishvara in one of its particular manifestations as their iṣṭa devatā, or chosen ideal.[316][317] The choice is a matter of individual preference,[318] and of regional and family traditions.[318][note 26] The multitude of Devas is considered manifestations of Brahman.[320]

The word avatar does not appear in the Vedic literature;[321] It appears in verb forms in post-Vedic literature, and as a noun particularly in the Puranic literature after the 6th century CE.[322] Theologically, the reincarnation idea is most often associated with the avatars of Hindu god Vishnu, though the idea has been applied to other deities.[323] Varying lists of avatars of Vishnu appear in Hindu scriptures, including the ten Dashavatara of the Garuda Purana and the twenty-two avatars in the Bhagavata Purana, though the latter adds that the incarnations of Vishnu are innumerable.[324] The avatars of Vishnu are important in Vaishnavism theology. In the goddess-based Shaktism tradition, avatars of the Devi are found and all goddesses are considered to be different aspects of the same metaphysical Brahman[325] and Shakti (energy).[326][327] While avatars of other deities such as Ganesha and Shiva are also mentioned in medieval Hindu texts, this is minor and occasional.[328]

Both theistic and atheistic ideas, for epistemological and metaphysical reasons, are profuse in different schools of Hinduism. The early Nyaya school of Hinduism, for example, was non-theist/atheist,[329] but later Nyaya school scholars argued that God exists and offered proofs using its theory of logic.[330][331] Other schools disagreed with Nyaya scholars. Samkhya,[332] Mimamsa[333] and Carvaka schools of Hinduism, were non-theist/atheist, arguing that "God was an unnecessary metaphysical assumption".[web 12][334][335] Its Vaisheshika school started as another non-theistic tradition relying on naturalism and that all matter is eternal, but it later introduced the concept of a non-creator God.[336][337][338] The Yoga school of Hinduism accepted the concept of a "personal god" and left it to the Hindu to define their god.[339] Advaita Vedanta taught a monistic, abstract Self and Oneness in everything, with no room for gods or deity, a perspective that Mohanty calls, "spiritual, not religious".[340] Bhakti sub-schools of Vedanta taught a creator God that is distinct from each human being.[307]

God in Hinduism is often represented having both the feminine and masculine aspects. The notion of the feminine in deity is much more pronounced and is evident in the pairings of Shiva with Parvati (Ardhanarishvara), Vishnu accompanied by Lakshmi, Radha with Krishna and Sita with Rama.[341]

According to Graham Schweig, Hinduism has the strongest presence of the divine feminine in world religion from ancient times to the present.[342] The goddess is viewed as the heart of the most esoteric Saiva traditions.[343]

Authority

[edit]Authority and eternal truths play an important role in Hinduism.[344] Religious traditions and truths are believed to be contained in its sacred texts, which are accessed and taught by sages, gurus, saints or avatars.[344] But there is also a strong tradition of the questioning of authority, internal debate and challenging of religious texts in Hinduism. The Hindus believe that this deepens the understanding of the eternal truths and further develops the tradition. Authority "was mediated through [...] an intellectual culture that tended to develop ideas collaboratively, and according to the shared logic of natural reason."[344] Narratives in the Upanishads present characters questioning persons of authority.[344] The Kena Upanishad repeatedly asks kena, 'by what' power something is the case.[344] The Katha Upanishad and Bhagavad Gita present narratives where the student criticises the teacher's inferior answers.[344] In the Shiva Purana, Shiva questions Vishnu and Brahma.[344] Doubt plays a repeated role in the Mahabharata.[344] Jayadeva's Gita Govinda presents criticism via Radha.[344]

Titles such as Guru, Acharya, or Mahacharya may be used to remark authority in Hindu and yogic traditions.

Practices

[edit]Rituals

[edit]

Most Hindus observe religious rituals at home.[346] The rituals vary greatly among regions, villages, and individuals. They are not mandatory in Hinduism. The nature and place of rituals is an individual's choice. Some devout Hindus perform daily rituals such as worshiping at dawn after bathing (usually at a family shrine, and typically includes lighting a lamp and offering foodstuffs before the images of deities), recitation from religious scripts, singing bhajans (devotional hymns), yoga, meditation, chanting mantras and others.[347]

Vedic rituals of fire-oblation (yajna) and chanting of Vedic hymns are observed on special occasions, such as a Hindu wedding.[348] Other major life-stage events, such as rituals after death, include the yajña and chanting of Vedic mantras.[web 13]

The words of the mantras are "themselves sacred,"[349] and "do not constitute linguistic utterances."[350] Instead, as Klostermaier notes, in their application in Vedic rituals they become magical sounds, "means to an end."[note 27] In the Brahmanical perspective, the sounds have their own meaning, mantras are considered "primordial rhythms of creation", preceding the forms to which they refer.[350] By reciting them the cosmos is regenerated, "by enlivening and nourishing the forms of creation at their base. As long as the purity of the sounds is preserved, the recitation of the mantras will be efficacious, irrespective of whether their discursive meaning is understood by human beings."[350][333]

Sādhanā

[edit]Sādhanā is derived from the root "sādh-", meaning "to accomplish", and denotes a means for the realisation of spiritual goals. Although different denominations of Hinduism have their own particular notions of sādhana, they share the feature of liberation from bondage. They differ on what causes bondage, how one can become free of that bondage, and who or what can lead one on that path.[351][352]

Life-cycle rites of passage

[edit]Major life stage milestones are celebrated as sanskara (saṃskāra, rites of passage) in Hinduism.[353][354] The rites of passage are not mandatory, and vary in details by gender, community and regionally.[355] Gautama Dharmasutras composed in about the middle of 1st millennium BCE lists 48 sanskaras,[356] while Gryhasutra and other texts composed centuries later list between 12 and 16 sanskaras.[353][357] The list of sanskaras in Hinduism include both external rituals such as those marking a baby's birth and a baby's name giving ceremony, as well as inner rites of resolutions and ethics such as compassion towards all living beings and positive attitude.[356]

The major traditional rites of passage in Hinduism include[355] Garbhadhana (pregnancy), Pumsavana (rite before the fetus begins moving and kicking in womb), Simantonnayana (parting of pregnant woman's hair, baby shower), Jatakarman (rite celebrating the new born baby), Namakarana (naming the child), Nishkramana (baby's first outing from home into the world), Annaprashana (baby's first feeding of solid food), Chudakarana (baby's first haircut, tonsure), Karnavedha (ear piercing), Vidyarambha (baby's start with knowledge), Upanayana (entry into a school rite),[358][359] Keshanta and Ritusuddhi (first shave for boys, menarche for girls), Samavartana (graduation ceremony), Vivaha (wedding), Vratas (fasting, spiritual studies) and Antyeshti (cremation for an adult, burial for a child).[360] In contemporary times, there is regional variation among Hindus as to which of these sanskaras are observed; in some cases, additional regional rites of passage such as Śrāddha (ritual of feeding people after cremation) are practised.[355][361]

Bhakti (worship)

[edit]Bhakti refers to devotion, participation in and the love of a personal god or a representational god by a devotee.[web 14][362] Bhakti-marga is considered in Hinduism to be one of many possible paths of spirituality and alternative means to moksha.[363] The other paths, left to the choice of a Hindu, are Jnana-marga (path of knowledge), Karma-marga (path of works), Rāja-marga (path of contemplation and meditation).[364][365]

Bhakti is practised in a number of ways, ranging from reciting mantras, japas (incantations), to individual private prayers in one's home shrine,[366] or in a temple before a murti or sacred image of a deity.[367][368] Hindu temples and domestic altars, are important elements of worship in contemporary theistic Hinduism.[369] While many visit a temple on special occasions, most offer daily prayers at a domestic altar, typically a dedicated part of the home that includes sacred images of deities or gurus.[369]

One form of daily worship is aarati, or "supplication", a ritual in which a flame is offered and "accompanied by a song of praise".[370] Notable aaratis include Om Jai Jagdish Hare, a Hindi prayer to Vishnu, and Sukhakarta Dukhaharta, a Marathi prayer to Ganesha.[371][372] Aarti can be used to make offerings to entities ranging from deities to "human exemplar[s]".[370] For instance, Aarti is offered to Hanuman, a devotee of God, in many temples, including Balaji temples, where the primary deity is an incarnation of Vishnu.[373] In Swaminarayan temples and home shrines, aarati is offered to Swaminarayan, considered by followers to be Supreme God.[374]

Other personal and community practices include puja as well as aarati,[375] kirtan, or bhajan, where devotional verses and hymns are read or poems are sung by a group of devotees.[web 15][376] While the choice of the deity is at the discretion of the Hindu, the most observed traditions of Hindu devotion include Vaishnavism, Shaivism, and Shaktism.[377] A Hindu may worship multiple deities, all as henotheistic manifestations of the same ultimate reality, cosmic spirit and absolute spiritual concept called Brahman.[378][379][320] Bhakti-marga, states Pechelis, is more than ritual devotionalism, it includes practices and spiritual activities aimed at refining one's state of mind, knowing god, participating in god, and internalising god.[380][381] While bhakti practices are popular and easily observable aspect of Hinduism, not all Hindus practice bhakti, or believe in god-with-attributes (saguna Brahman).[382][383] Concurrent Hindu practices include a belief in god-without-attributes (nirguna Brahman), and god within oneself.[384][385]

Festivals

[edit]

Hindu festivals (Sanskrit: Utsava; literally: "to lift higher") are ceremonies that weave individual and social life to dharma.[386][387] Hinduism has many festivals throughout the year, where the dates are set by the lunisolar Hindu calendar, many coinciding with either the full moon (Holi) or the new moon (Diwali), often with seasonal changes.[388] Some festivals are found only regionally and they celebrate local traditions, while a few such as Holi and Diwali are pan-Hindu.[388][389] The festivals typically celebrate events from Hinduism, connoting spiritual themes and celebrating aspects of human relationships such as the sister-brother bond over the Raksha Bandhan (or Bhai Dooj) festival.[387][390] The same festival sometimes marks different stories depending on the Hindu denomination, and the celebrations incorporate regional themes, traditional agriculture, local arts, family get togethers, Puja rituals and feasts.[386][391]

Some major regional or pan-Hindu festivals include:

- Ashadhi Ekadashi

- Bonalu

- Chhath

- Dashain

- Diwali or Tihar or Deepawali

- Durga Puja

- Dussehra

- Ganesh Chaturthi

- Gowri Habba

- Gudi Padwa

- Holi

- Karva Chauth

- Kartika Purnima

- Krishna Janmashtami

- Maha Shivaratri

- Makar Sankranti

- Navaratri

- Onam

- Pongal

- Radhashtami

- Raksha Bandhan

- Rama Navami

- Ratha Yatra

- Sharad Purnima

- Shigmo

- Thaipusam

- Ugadi

- Vasant Panchami

- Vishu

Pilgrimage

[edit]Many adherents undertake pilgrimages, which have historically been an important part of Hinduism and remain so today.[392] Pilgrimage sites are called Tirtha, Kshetra, Gopitha or Mahalaya.[393][394] The process or journey associated with Tirtha is called Tirtha-yatra.[395] According to the Hindu text Skanda Purana, Tirtha are of three kinds: Jangam Tirtha is to a place movable of a sadhu, a rishi, a guru; Sthawar Tirtha is to a place immovable, like Benaras, Haridwar, Mount Kailash, holy rivers; while Manas Tirtha is to a place of mind of truth, charity, patience, compassion, soft speech, Self.[396][397] Tīrtha-yatra is, states Knut A. Jacobsen, anything that has a salvific value to a Hindu, and includes pilgrimage sites such as mountains or forests or seashore or rivers or ponds, as well as virtues, actions, studies or state of mind.[398][399]

Pilgrimage sites of Hinduism are mentioned in the epic Mahabharata and the Puranas.[400][401] Most Puranas include large sections on Tirtha Mahatmya along with tourist guides,[402] which describe sacred sites and places to visit.[403][404][405] In these texts, Varanasi (Benares, Kashi), Rameswaram, Kanchipuram, Dwarka, Puri, Haridwar, Sri Rangam, Vrindavan, Ayodhya, Tirupati, Mayapur, Nathdwara, twelve Jyotirlinga and Shakti Pitha have been mentioned as particularly holy sites, along with geographies where major rivers meet (sangam) or join the sea.[406][401] Kumbh Mela is another major pilgrimage on the eve of the solar festival Makar Sankranti. This pilgrimage rotates at a gap of three years among four sites: Prayagraj at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, Haridwar near source of the Ganges, Ujjain on the Shipra river and Nashik on the bank of the Godavari river.[407] This is one of world's largest mass pilgrimage, with an estimated 40 to 100 million people attending the event.[407][408][web 16] At this event, they say a prayer to the sun and bathe in the river,[407] a tradition attributed to Adi Shankara.[409]

Some pilgrimages are part of a Vrata (vow), which a Hindu may make for a number of reasons.[410][411] It may mark a special occasion, such as the birth of a baby, or as part of a rite of passage such as a baby's first haircut, or after healing from a sickness.[412][413] It may also be the result of prayers answered.[412] An alternative reason for Tirtha, for some Hindus, is to respect wishes or in memory of a beloved person after their death.[412] This may include dispersing their cremation ashes in a Tirtha region in a stream, river or sea to honour the wishes of the dead. The journey to a Tirtha, assert some Hindu texts, helps one overcome the sorrow of the loss.[412][note 28]

Other reasons for a Tirtha in Hinduism is to rejuvenate or gain spiritual merit by travelling to famed temples or bathe in rivers such as the Ganges.[416][417][418] Tirtha has been one of the recommended means of addressing remorse and to perform penance, for unintentional errors and intentional sins, in the Hindu tradition.[419][420] The proper procedure for a pilgrimage is widely discussed in Hindu texts.[421] The most accepted view is that the greatest austerity comes from travelling on foot, or part of the journey is on foot, and that the use of a conveyance is only acceptable if the pilgrimage is otherwise impossible.[422]

Culture

[edit]The term "Hindu culture" refers to mean aspects of culture that pertain to the religion, such as festivals and dress codes followed by the Hindus which is mainly can be inspired from the culture of India and Southeast Asia.

Architecture

[edit]Hindu architecture is the traditional system of Indian architecture for structures such as temples, monasteries, statues, homes, market places, gardens and town planning as described in Hindu texts.[423][424] The architectural guidelines survive in Sanskrit manuscripts and in some cases also in other regional languages. These texts include the Vastu shastras, Shilpa Shastras, the Brihat Samhita, architectural portions of the Puranas and the Agamas, and regional texts such as the Manasara among others.[425][426]

By far the most important, characteristic and numerous surviving examples of Hindu architecture are Hindu temples, with an architectural tradition that has left surviving examples in stone, brick, and rock-cut architecture dating back to the Gupta Empire. These architectures had influence of Ancient Persian and Hellenistic architecture.[427] Far fewer secular Hindu architecture have survived into the modern era, such as palaces, homes and cities. Ruins and archaeological studies provide a view of early secular architecture in India.[428]

Studies on Indian palaces and civic architectural history have largely focussed on the Mughal and Indo-Islamic architecture particularly of the northern and western India given their relative abundance. In other regions of India, particularly the South, Hindu architecture continued to thrive through the 16th-century, such as those exemplified by the temples, ruined cities and secular spaces of the Vijayanagara Empire and the Nayakas.[429][430] The secular architecture was never opposed to the religious in India, and it is the sacred architecture such as those found in the Hindu temples which were inspired by and adaptations of the secular ones. Further, states Harle, it is in the reliefs on temple walls, pillars, toranas and madapams where miniature version of the secular architecture can be found.[431]

Art

[edit]

Hindu art encompasses the artistic traditions and styles culturally connected to Hinduism and have a long history of religious association with Hindu scriptures, rituals and worship.

Calendar

[edit]The Hindu calendar, Panchanga (Sanskrit: पञ्चाङ्ग) or Panjika is one of various lunisolar calendars that are traditionally used in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, with further regional variations for social and Hindu religious purposes. They adopt a similar underlying concept for timekeeping based on sidereal year for solar cycle and adjustment of lunar cycles in every three years, but differ in their relative emphasis to moon cycle or the sun cycle and the names of months and when they consider the New Year to start.[432] Of the various regional calendars, the most studied and known Hindu calendars are the Shalivahana Shaka (Based on the King Shalivahana, also the Indian national calendar) found in the Deccan region of Southern India and the Vikram Samvat (Bikrami) found in Nepal and the North and Central regions of India – both of which emphasise the lunar cycle. Their new year starts in spring. In regions such as Tamil Nadu and Kerala, the solar cycle is emphasised and this is called the Tamil calendar (though Tamil calendar uses month names like in Hindu Calendar) and Malayalam calendar and these have origins in the second half of the 1st millennium CE.[432][433] A Hindu calendar is sometimes referred to as Panchangam (पञ्चाङ्गम्), which is also known as Panjika in Eastern India.[434]

The ancient Hindu calendar conceptual design is also found in the Hebrew calendar, the Chinese calendar, and the Babylonian calendar, but different from the Gregorian calendar.[435] Unlike the Gregorian calendar which adds additional days to the month to adjust for the mismatch between twelve lunar cycles (354 lunar days)[436] and nearly 365 solar days, the Hindu calendar maintains the integrity of the lunar month, but inserts an extra full month, once every 32–33 months, to ensure that the festivals and crop-related rituals fall in the appropriate season.[435][433]

The Hindu calendars have been in use in the Indian subcontinent since Vedic times, and remain in use by the Hindus all over the world, particularly to set Hindu festival dates. Early Buddhist communities of India adopted the ancient Vedic calendar, later Vikrami calendar and then local Buddhist calendars. Buddhist festivals continue to be scheduled according to a lunar system.[437] The Buddhist calendar and the traditional lunisolar calendars of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand are also based on an older version of the Hindu calendar. Similarly, the ancient Jain traditions have followed the same lunisolar system as the Hindu calendar for festivals, texts and inscriptions. However, the Buddhist and Jain timekeeping systems have attempted to use the Buddha and the Mahavira's lifetimes as their reference points.[438][439][440]

The Hindu calendar is also important to the practice of Hindu astrology and zodiac system. It is also employed for observing the auspicious days of deities and occasions of fasting, such as Ekadashi.[441]

Physical culture

[edit]Person and society

[edit]Varnas

[edit]

Hindu society has been categorised into four classes, called varṇas. They are the Brahmins: Vedic teachers and priests; the Kshatriyas: warriors and kings; the Vaishyas: farmers and merchants; and the Shudras: servants and labourers.[442] The Bhagavad Gītā links the varṇa to an individual's duty (svadharma), inborn nature (svabhāva), and natural tendencies (guṇa).[443] The Manusmriti categorises the different castes.[web 17] Some mobility and flexibility within the varṇas challenge allegations of social discrimination in the caste system, as has been pointed out by several sociologists,[444][445] although some other scholars disagree.[446] Scholars debate whether the so-called caste system is part of Hinduism sanctioned by the scriptures or social custom.[447][web 18][note 29] And various contemporary scholars have argued that the caste system was introduced by the British colonial regime; which is indeed false as it existed even before the westerners came to India.[448]

A renunciant man of knowledge is usually called Varṇatita or "beyond all varṇas" in Vedantic works. The bhiksu is advised to not bother about the caste of the family from which he begs his food. Scholars like Adi Sankara affirm that not only is Brahman beyond all varṇas, the man who is identified with Him also transcends the distinctions and limitations of caste.[449]

Yoga

[edit]

In whatever way a Hindu defines the goal of life, there are several methods (yogas) that sages have taught for reaching that goal. Yoga is a Hindu discipline which trains the body, mind, and consciousness for health, tranquility, and spiritual insight.[450] Texts dedicated to yoga include the Yoga Sutras, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Bhagavad Gita and, as their philosophical and historical basis, the Upanishads. Yoga is means, and the four major marga (paths) of Hinduism are: Bhakti Yoga (the path of love and devotion), Karma Yoga (the path of right action), Rāja Yoga (the path of meditation), and Jñāna Yoga (the path of wisdom)[451] An individual may prefer one or some yogas over others, according to their inclination and understanding. Practice of one yoga does not exclude others. The modern practice of yoga as exercise (traditionally Hatha yoga) has a contested relationship with Hinduism.[452]

Symbolism

[edit]

Hinduism has a developed system of symbolism and iconography to represent the sacred in art, architecture, literature and worship. These symbols gain their meaning from the scriptures or cultural traditions. The syllable Om (which represents the Brahman and Atman) has grown to represent Hinduism itself, while other markings such as the Swastika (from the Sanskrit: स्वस्तिक, romanized: svastika) a sign that represents auspiciousness,[453] and Tilaka (literally, seed) on forehead – considered to be the location of spiritual third eye,[454] marks ceremonious welcome, blessing or one's participation in a ritual or rite of passage.[455] Elaborate Tilaka with lines may also identify a devotee of a particular denomination. Flowers, birds, animals, instruments, symmetric mandala drawings, objects, lingam, idols are all part of symbolic iconography in Hinduism.[456][457] [458]

Ahiṃsā and food customs

[edit]Hindus advocate the practice of ahiṃsā (nonviolence) and respect for all life because divinity is believed to permeate all beings, including plants and non-human animals.[459] The term ahiṃsā appears in the Upanishads,[460] the epic Mahabharata[461] and ahiṃsā is the first of the five Yamas (vows of self-restraint) in Patanjali's Yoga Sutras.[462] Hindu texts such as Śāṇḍilya Upanishad[463] and Svātmārāma[464][465] recommend Mitahara (eating in moderation) as one of the Yamas (virtuous Self restraints). According to Hindu beliefs, food affects the body, mind, and spirit.[466][467] The Bhagavad Gita links body and mind to food one consumes in verses 17.8 through 17.10.[468]