Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shkodër

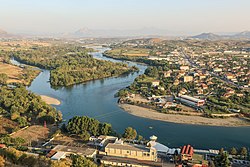

View on WikipediaShkodër (/ˈʃkoʊdər/ SHKOH-dər,[7] Albanian: [ˈʃkɔdəɾ]; Albanian definite form: Shkodra; historically known as Scodra or Scutari) is the fifth-most-populous city of Albania and the seat of Shkodër County and Shkodër Municipality. Shkodër has been continuously inhabited since the Early Bronze Age (c. 2250–2000 BC),[8][9] and has roughly 2,200 years of recorded history. The city sprawls across the Plain of Mbishkodra between the southern part of Lake Shkodër and the foothills of the Albanian Alps on the banks of the Buna, Drin and Kir rivers.[10] Due to its proximity to the Adriatic Sea, Shkodër is affected by a seasonal Mediterranean climate with continental influences.[10]

Key Information

An urban settlement called Skodra was founded by the Illyrian tribe of Labeatae in the 4th century BCE.[11][12] It became the capital of the Illyrian kingdom under the Ardiaei and Labeatae and was one of the most important cities of the Balkans in ancient times.[13] It has historically developed on a 130 m (430 ft) hill strategically located in the outflow of Lake Shkodër into the Buna. The Romans annexed the city after the third Illyrian War in 168 BC, when the Illyrian king Gentius was defeated by the Roman force of Anicius Gallus.[14][15] In the 3rd century AD, Shkodër became the capital of Praevalitana, due to the administrative reform of the Roman Emperor Diocletian. With the spread of Christianity in the 4th century AD, the Archdiocese of Scodra was founded and was assumed in 535 by Byzantine Emperor Justinian I.

Shkodër is regarded as the traditional capital of northern Albania, also referred to as Gegëria, and is noted for its arts, culture, religious diversity, and turbulent history among the Albanians. The architecture of Shkodër is particularly dominated by mosques and churches reflecting the city's high degree of religious diversity and tolerance. Shkodër was home to many influential personalities, who among others, helped to shape the Albanian Renaissance.

Name

[edit]The city was first attested in classical sources as the capital of the Illyrian kingdom with the name Skodra (Ancient Greek: Σκόδρα, with the ethnonymic genitive Σκοδρινῶν "of the Skodrians", appearing on 2nd c. BC coins) and Scodra (Latin form).[16][17][18]

Although the ultimate origin of the toponym Σκόδρα Scodra is uncertain,[19] the name is certainly pre-Roman. A Paleo-Balkan origin has been suggested, relating it to the Albanian: kodër (definite form: kodra) 'hill', and Romanian: codru '(wooded) mountain, forest', with the same root as the ancient toponym Codrio/Kodrion.[20]

The further development of the name has been a subject of discussion in Albanian historical linguistics. Some linguists treat the development from Illyrian Σκόδρα Skodra to Albanian Shkodra/Shkodër as evidence of regular development within the Albanian language. Others have argued that Albanian Shkodra/Shkodër fails to display certain known phonological changes that would have to have happened if the name had been continually in use in Proto-Albanian since pre-Roman times, based on the fact that */sk-/ consonant clusters are usually morphed into a */h-/, and not */ʃk-/, and o is morphed into a, not preserved.[19][21][22] However, the phonetic changes sk > h and o > a occurred at an early stage of Proto-Albanian, because they regularly do not involve early Greek and Latin loanwords. Contacts of Albanian with Greek date back as early as the 7th century BC since the foundation of the Greek colonies on the Adriatic coast of Albania, hence those phonetic changes in Proto-Albanian certainly predate the foundation of Skodra (4th century BC) and the usage of its name. On the other hand, the o in Shkodër would postdate first contacts with Latin, because in the earliest Latin loanwords in Albanian the ŏ is rendered as u.[23] The preservation of ŏ in the Albanian form is to be explained probably because Latin was the predominant language of the Adriatic coastal areas, naturally exercising a significant pressure and influencing the linguistic forms of the local toponyms in Albanian. Similar cases of this process can be seen in the old Albanian toponym Trieshtë, which evolved regularly through Albanian phonetic changes from Trieste, but which was recently replaced in Albanian under strong pressure from Italian into the current name Trieste; and the old Albanian toponym Gjenòvë, which evolved regularly through Albanian phonetic changes form Genova, also featuring the characteristic Albanian accent rule.[24] Nevertheless, the Albanian toponym Shkodër certainly predates the end of the ancient Roman period.[25][26][22][27]

In modern times, the term was adapted to Italian as Scodra (Italian pronunciation: [ˈskɔːdra]) and Scutari ([ˈskuːtari]); in this form it was also in wide use in English until the 20th century.[28][citation needed] In Serbo-Croatian, Shkodër is known as Skadar (Serbo-Croatian Cyrillic: Скадар), and in Turkish as İşkodra.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

The earliest signs of human activity in the lands of Shkodër can be traced back to the Middle Paleolithic (120,000–30,000 years ago).[29] Artifacts and faunal remains provide evidence that the first inhabitants of the area of Shkodër were Pleistocene hunter-gatherers.[30] Presence of Neolithic farmers is also testified by artifacts. The Copper and Early Bronze Ages constitute an important watershed for the social evolution on the territories of the eastern Adriatic coast, including Shkodër, with the formation of new cultures and the beginning of new complex historical, ethnogenetic and cultural processes. This period represents for Shkodër the first step of a process of occupation and development. The inhabitants of the intensively settled Shkodër basin produced pottery, practiced agriculture, and manufactured metal tools.[30] Shkodra's Early Bronze Age culture bears many similarities with the culture of the Eastern Adriatic coast and its hinterland, like the Cetina culture, and it also has connections with the Early Bronze Age culture of Maliq in southeastern Albania. During the developed Early Bronze Age the new practice of tumulus burials appears, which may be associated to Indo-European migrations from the steppes. During the Middle and Late Bronze Age the settlements in the region and extraregional interactions apparently increased. In the Late Bronze Age the inhabitants of Shkodra basin had contacts with Italy or northwest Greece. By the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age (c. 1100–800 BC), the formation of a large, cohesive, and quite homogeneous cultural group had already occurred in a well defined territory of the Shkodra region, which was referred in historical sources to as 'the tribe of the Labeatae' in later times.[11]

The favorable conditions on the fertile plain, around the lake, have brought people here in early antiquity. Artefacts and inscriptions, discovered in the Rozafa Castle, are assumed to be the earliest examples of symbolic behaviour in humans in the city. Although, it was known under the name Scodra and was inhabited by the Illyrian tribes of the Labeates and Ardiaei, which ruled over a large territory between modern Albania up to Croatia.[31][32][33] King Agron, Queen Teuta and King Gentius, were among the most famous personalities of the Ardiaei.

The city was first mentioned during antiquity as the site of the Illyrian Labeates in which they minted coins and that of Queen Teuta.[34] In 168 BC, the city was captured by the Romans and became an important trade and military route. The Romans colonized[35] the town. Scodra remained in the province of Illyricum and, later, Dalmatia. By it 395 AD, it was part of the Diocese of Dacia, within Praevalitana. After the split of the Roman Empire, Shkodra was taken by the Byzantines.[36]

In the early 11th century, Jovan Vladimir ruled Duklja amidst the war between Basil II and Samuel. Vladimir allegedly retreated into Koplik when Samuel invaded Duklja and was subsequently forced to accept Bulgarian vassalage. He was later slain by the Bulgarians. Shingjon (feast of Jovan Vladimir) has since been celebrated by Albanian Orthodox Christians.[37]

In the 1030s, Stefan Vojislav from Travunija, then part of Medieval Serbia,[citation needed] expelled the last strategos and successfully defeated the Byzantines by 1042. Stefan Vojislav set up Shkodër, as his capital.[38] Constantine Bodin accepted the crusaders of the Crusade of 1101 in Shkodër. After the dynastic struggles in the 12th century, Shkodër became an integral part of the Serbian Nemanjić Zeta province. In 1214 the city was briefly annexed to Despotate of Epirus under Michael I Komnenos Doukas.[39] In 1330, Stefan Dečanski, King of Serbia, appointed his son Stefan Dušan as the governor of Zeta with its seat in Shkodër.[40] In the same year Dušan and his father entered the conflict which resulted with campaign of Dečanski who destroyed Dušan's court on Drin River near Shkodër in January 1331. In April 1331, they made a truce,[41] but in August 1331 Dušan went from Shkodër to Nerodimlje and overthrew his father.[42]

During the disintegration of the Serbian Empire, Shkodër was taken by the Albanian Balshaj family, who surrendered the city to the Republic of Venice in 1396, in order to form a protection zone from the Ottoman Empire. During the Venetian rule the city adopted the Statutes of Scutari, a civic law written in Venetian. The Statutes of Scutari mention Albanian and Slavic presence in the city, but under Venetian rule many Dalmatians were brought to Shkodra and as such formed the majority there. After the Black Death killed most of the inhabitants Albanians and Slavs formed the majority in the city.[43] Venetians built the St. Stephen's Church (later converted into the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Mosque by the Ottomans) and the Rozafa Castle. In 1478-79 Mehmed the conqueror laid siege on Shkodër. In 1479 the city fell to the Ottomans and the defenders of the citadel emigrated to Venice, while many Albanians from the region retreated into the mountains. On the other hand the upper classes of the city, aided by the Jonima family settled in the cities of Ravena, Venice and Treviso. The city then became a seat of a newly established Ottoman sanjak, the Sanjak of Scutari.

Ottoman period

[edit]

With two sieges, Shkodër became secure as an Ottoman territory. It became the centre of the sanjak and by 1485 there were 27 Muslim and 70 Christian hearths, although by the end of the next century there were more than 200 Muslim ones compared to the 27 Christian ones, respectively.[44]

Military manoeuvres in 1478 by the Ottomans meant that the city was again entirely surrounded by Ottoman forces. Mehmed II personally laid the siege. About ten heavy cannons were cast on site. Balls as heavy as 380 kg (838 lb) were fired on the citadel (such balls are still on display on the castle museum). Nevertheless, the city resisted. Mehmed left the field and had his commanders continue the siege. By the winter the Ottomans had captured one after the other all adjacent castles: Lezhë, Drisht and Žabljak Crnojevića. This, together with famine and constant bombardment lowered the morale of defenders. On the other hand, the Ottomans were already frustrated by the stubborn resistance. The castle is situated on a naturally protected hill and every attempted assault resulted in considerable casualties for the attackers. A truce became an option for both parties. On January 25 an agreement between the Venetians and the Ottoman Empire ended the siege, permitting the citizens to leave unharmed, and the Ottomans to take over the deserted city.

After Ottoman domination was secure, much of the population fled. Around the 17th century, the city began to prosper as the centre of the Sanjak of Scutari (sanjak was an Ottoman administrative unit smaller than a vilayet). It became the economic centre of northern Albania, its craftsmen producing fabric, silk, arms and silver artifacts. Construction included two-storey stone houses, the souk, and the Mesi Bridge (Ura e Mesit) over the Kir river, built during the second half of the 18th century, over 100 m (330 ft) long, with 13 arcs of stone, the largest one being 22 m (72 ft) wide and 12 m (39 ft) tall.

Shkodër was a major city under Ottoman rule in southeast Europe. It retained its importance up until the end of the empire's rule in the Balkans in the early 20th century. This is due to its geo-strategic position that connects it directly with the Adriatic and with the Italian ports, but also with land-routes to the other important Ottoman centre, namely Prizren. The city was an important meeting place of diverse cultures from other parts of the Empire, as well as influences coming westwards, by Italian merchants. It was a centre of Islam in the region, producing many ulama, poets and administrators, particularly from the Bushati family. In the 18th century Shkodër became the centre of the (pashaluk) of Shkodër, under the rule of the Bushati family, which ruled from 1757 to 1831.

In 1737, 178 Catholic families were recorded in Shkodër, all of them Albanian.[46]

Shkodër's importance as a trade centre in the second half of the 19th century was owed to the fact that it was the centre of the vilayet of Shkodër, and an important trading centre for the entire Balkan peninsula. It had over 3,500 shops, and clothing, leather, tobacco and gunpowder were some of the major products of Shkodër. A special administration was established to handle trade, a trade court, and a directorate of postage services with other countries. Other countries had opened consulates in Shkodër ever since 1718. Obot and Ulcinj served as ports for Shkodër, and, later on, Shëngjin (San Giovanni di Medua). The Jesuit seminary and the Franciscan committee were opened in the 19th century.

Following the rebellion of Mustafa Pasha Bushatlliu Shkodër was sieged by the Ottomans for more than six months who finally managed to break the Albanian resistance on 10 November 1831. In 1833 around 4,000 Albanian rebels seized the town again holding off the Ottoman forces between April and December and even sending a delegation to Istanbul until the Ottoman government finally gave in to their terms giving an end to the rebellion.

Before 1867 Shkodër (İşkodra) was a sanjak of Rumelia Eyalet in Ottoman Empire. In 1867, Shkodër sanjak merged with Skopje (Üsküp) sanjak and became Shkodër vilayet. Shkodër vilayet was split into Shkodër, Prizren and Dibra sanjaks. In 1877, Prizren passed to Kosovo vilayet and Debar passed to Monastir vilayet, while Durrës township became a sanjak. In 1878 Bar and Podgorica townships belonged to Montenegro. Ottoman-Albanian intellectual Sami Frashëri during the 1880s estimated the population of Shkodër as numbering 37,000 inhabitants that consisted of three quarters being Muslims and the rest Christians made up of mostly Catholics and a few hundred Orthodox.[47] In 1900, Shkodër vilayet was split into Shkodër and Durrës sanjaks.

Modern

[edit]

Shkodër played an important role during the League of Prizren, the Albanian liberation movement. The people of Shkodër participated in battles to protect Albanian land. The branch of the League of Prizren for Shkodër, which had its own armed unit, fought for the protection of Plav, Gusinje, Hoti and Gruda, and the war for the protection of Ulcinj. The Bushati Library, built during the 1840s, served as a centre for the League of Prizren's branch for Shkodër. Many books were collected in libraries of Catholic missionaries working in Shkodër. Literary, cultural and sports associations were formed, such as Bashkimi ("The Union") and Agimi ("The Dawn"). The first Albanian newspapers and publications printed in Albania came out of the printing press of Shkodër. The Marubi family of photographers began working in Shkodër, which left behind over 150,000 negatives from the period of the Albanian liberation movement, the rise of the Albanian flag in Vlorë, and life in Albanian towns during the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

During the Balkan Wars, Shkodër went from one occupation to another, when the Ottomans were defeated by the Kingdom of Montenegro. The Ottoman forces led by Hasan Riza Pasha and Esad Pasha had resisted for seven months the siege of the town by Montenegrin forces and their Serbian allies. Esad (Hasan had previously been mysteriously killed by Essad Toptani in an ambush inside the town) finally surrendered to Montenegro in April 1913, after Montenegro suffered a high death toll with more than 10,000 casualties. Edith Durham also notes the cruelties suffered at the hand of Montenegrins in the wake of October 1913: "Thousands of refugees arriving from Djakovo and neighbourhood. Victims of Montenegro. My position was indescribably painful, for I had no funds left, and women came to me crying: 'If you will not feed my child, throw it in the river. I cannot see it starve.'"[48] Montenegro was compelled to leave the city to the new country of Albania in May 1913, in accordance with the London Conference of Ambassadors.

During World War I, Montenegrin forces again occupied Shkodër on 27 June 1915. In January 1916, Shkodër was taken over by Austria-Hungary and was the centre of the zone of their occupation. When the war ended on 11 November 1918, French forces occupied Shkodër as well as other regions with sizable Albanian populations. After World War I, the international military administration of Albania was temporarily located in Shkodër, and in March 1920, Shkodër was put under the administration of the national government of Tirana. In the second half of 1920, during the Serbian-Albanian War, Shkodër resisted the Serbian invasion under the lead of Sylço Bushati and financial aid provided by notable figures such as Musa Juka.[49]

Shkodër was the centre of democratic movements of the years 1921–1924. The democratic opposition won the majority of votes for the Constitutional Assembly, and on 31 May 1924, the democratic forces took over the town and from Shkodër headed to Tirana. From 1924 to 1939, Shkodër had a slow industrial development, small factories that produced food, textile and cement were opened. From 43 of such in 1924, the number rose to 70 in 1938. In 1924, Shkodër had 20,000 inhabitants, the number grew to 29,000 in 1938. During September 1928, Albania was proclaimed a monarchy by King Zog I. He was a self-made Muslim monarch and the king of all Albanians until 1939 when Italy invaded Albania, Shkoder resisted under the lead of Mehmet Ullagaj but fell soon afterwards.[50] After 1939, Zog went into exile and Victor Emmanuel III became the king of the Albanians. Shortly after World War II, Emmanuel was formally abdicated in 1946. In 1945, Enver Hoxha established communism in Albania. The communist regime repressed many religious people, mostly Catholic, but also some Muslims, and intellectuals, who opposed the communist ideology. Shkodra may be one of the cities with the most political prisoners during the communist regime. The famous Shkodër Bazaar (Albanian: Pazari i Shkodrës) and the port on the Buna river were completely demolished by the communists, ending the centuries of a flourishing economic and trade center, but also reducing the city's strategic importance. as [51]

Shkodër was the seat of a Catholic archbishopric and had a number of religious schools. The first laic school was opened here in 1913, and the State Gymnasium was opened in 1922. It was the centre of many cultural associations. In sports Shkodër was the first city in Albania to constitute a sports association, the "Vllaznia" (brotherhood). Vllaznia Shkodër is the oldest sport club in Albania.

During the early 1990s, Shkodër was once again a major centre, this time of the democratic movement that finally brought to an end the communist regime established by Enver Hoxha. In the later 2000s (decade), the city experiences a rebirth as main streets are being paved, buildings painted and streets renamed. In December 2010, Shkodër and the surrounding region was hit by probably the worst flooding in the last 100 years.[52] In 2011, a new swing bridge over the Buna was constructed, thus replacing the old bridge nearby.

Geography

[edit]

Shkodër extends strategically on the Mbishkodra Plain between the Lake of Shkodër and the foothills of the Albanian Alps, which forms the southern continuation of the Dinaric Alps. The northeast of the city is dominated by Mount Maranaj standing at 1,576 m (5,171 ft) above the Adriatic. Shkodër is trapped on three sides by Kir in the east, Drin in the south and Buna in the west. Rising from the Lake of Shkodër, Buna flows into the Adriatic Sea, forming the border with Montenegro. The river joins the Drin for approximately 2 km (1.2 mi) southwest of the city. In the east, Shkodër is bordered by Kir, which originates from the north flowing also into the Drin, that surrounds Shkodër in the south. The area of the municipality of Shkodër is 872.71 km2 (336.96 sq mi);[1][2] the area of the municipal unit of Shkodër (the city proper) is 16.46 km2 (6.36 sq mi).[3]

Lake Shkodër lies in the west of the city and forms the frontier of Albania and Montenegro. The lake became the symbol of the stable and consistent economic and social divide of the city. Although, the lake is the largest lake in Southern Europe and an important habitat for various animal and plant species. Further, the Albanian section has been designated as a nature reserve. In 1996, it also has been recognised as a wetland of international importance by designation under the Ramsar Convention.[53] Buna connects the lake with the Adriatic Sea, while the Drin provides a link with Lake Ohrid in the southeast of Albania.[54] It is a cryptodepression, filled by the river Morača and drained into the Adriatic by the 41-kilometre-long (25 mi) Buna.

Climate

[edit]Shköder has a borderline hot-summer Mediterranean (Köppen: Csa) and humid subtropical (Köppen: Cfa) climate.[55] Mean monthly temperature ranges between 1.8 °C (35.2 °F) to 10.3 °C (50.5 °F) in January and 20.2 °C (68.4 °F) to 33.6 °C (92.5 °F) in August. The average yearly precipitation is about 1,500 mm (59.1 in), which makes the area one of the wettest in Europe.

| Climate data for Shkodër (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1951–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.6 (65.5) |

27.6 (81.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

30.5 (86.9) |

34.5 (94.1) |

38.2 (100.8) |

43.0 (109.4) |

42.6 (108.7) |

37.6 (99.7) |

31.0 (87.8) |

25.0 (77.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

42.6 (108.7) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.3 (79.3) |

30.1 (86.2) |

34.8 (94.6) |

37.4 (99.3) |

38.1 (100.6) |

32.9 (91.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

22.3 (72.1) |

16.7 (62.1) |

38.5 (101.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

32.9 (91.2) |

33.6 (92.5) |

27.7 (81.9) |

22.1 (71.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

7.9 (46.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

23.3 (73.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

16.9 (62.4) |

11.8 (53.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

3.3 (37.9) |

6.1 (43.0) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.1 (66.4) |

20.2 (68.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

11.7 (53.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

3.7 (38.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −3.5 (25.7) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

0.7 (33.3) |

3.9 (39.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.3 (52.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

15.8 (60.4) |

10.5 (50.9) |

6.2 (43.2) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13.0 (8.6) |

−12.4 (9.7) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

3.6 (38.5) |

2.0 (35.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 130.3 (5.13) |

138.3 (5.44) |

140.1 (5.52) |

127.2 (5.01) |

82.9 (3.26) |

35.8 (1.41) |

42.7 (1.68) |

37.5 (1.48) |

161.8 (6.37) |

167.7 (6.60) |

212.5 (8.37) |

188.0 (7.40) |

1,471.5 (57.93) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.31 | 9.63 | 10.65 | 10.04 | 9.02 | 4.20 | 3.41 | 3.90 | 7.36 | 9.23 | 11.90 | 10.76 | 99.40 |

| Average snowy days | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 5.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 72.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 2,369.2 |

| Source 1: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)[56] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: meteo-climat-bzh[57][58] | |||||||||||||

Governance

[edit]Shkodër is a municipality governed by a mayor–council system with the mayor of Shkodër and the members of Shkodër Municipal Council responsible for the administration of Shkodër Municipality.[3] The municipality is encompassed in Shkodër County within the Northern Region of Albania and consists of the administrative units of Ana e Malit, Bërdicë, Dajç, Guri i Zi, Postribë, Pult, Rrethinat, Shalë, Shosh, Velipojë and Shkodër as its seat.[59][60]

International relations

[edit]Shkodër is twinned with:

Economy

[edit]The main activities of the processing industry in Shkodra were the processing of tobacco and manufacture of cigarettes, production of preserved foods, sugar-based foods, soft and alcoholic drinks, and pasta, bread, rice and vegetable oil. The main activities of the textile industry were focused on garments and silk products. The city also had a wood-processing and paper-production plant. The most important mechanical engineering industries concerned wire manufacturing, elevator manufacturing, bus assembly and the Drini Plant.[66]

According to the World Bank, Shkodër has had significant steps of improving the economy in recent years. In 2016, Shkodër ranked 8[67] among 22 cities in southeastern Europe.

As the largest city in northern Albania, the city is the main road connection between the Albanian capital, Tirana and Montenegrin capital Podgorica. The SH1 leads to the Albanian–Montenegrin border at Han i Hotit border crossing. From Tirana at the Kamza Bypass northward, it passes through Fushë-Kruja, Milot, Lezha, Shkodra and Koplik. The road segment between Hani i Hotit at the Montenegrin border and Shkodra was completed in 2013 as a single carriageway standard. Shkodër Bypass started after the 2010 Albania floods. It was planned to incorporate a defensive dam against Shkodër Lake but works were abandoned a few years later. The road continues as a single carriageway down to Milot and contains some uncontrolled and dangerous entry and exit points. The SH5 starts from Shkodër to Morinë.

Demography

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1918 | 22,631 | — |

| 1923 | 23,784 | +5.1% |

| 1930 | 29,209 | +22.8% |

| 1950 | 33,638 | +15.2% |

| 1960 | 43,305 | +28.7% |

| 1969 | 52,200 | +20.5% |

| 1979 | 65,000 | +24.5% |

| 1989 | 81,140 | +24.8% |

| 2001 | 83,598 | +3.0% |

| 2011 | 77,075 | −7.8% |

| 2023 | 61,633 | −20.0% |

| Source: [68][69][70][6] | ||

Shkodër is the fourth-most-populous city and fifth-most-populous municipality in Albania. As of the 2011 census, the municipal unit of Shkodër had an estimated population of 77,075 of whom 37,630 were men and 39,445 women.[71] The population of the municipality was 135,612 in 2011.[a][71]

The city of Shkodër was one of the most important centres for Islamic scholars and cultural and literary activity in Albania. Here stands the site of the only institution in Albania which provides high-level education in Arabic, Turkish and Islamic Studies.[73] Shkodër is the centre of Roman Catholicism in Albania. The Roman Catholic Church is represented in Shkodër by the episcopal seat of the Metropolitan Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Shkodër-Pult (Scutari-Pulati) in Shkodër Cathedral, with the current seat of the prelacy.

Culture

[edit]

Shkodër is referred to as the capital and cultural cradle of northern Albania, also known as Gegëria, for having been the birthplace and home of notable individuals, who among others contributed to the Albanian Renaissance.[3][74] Most of the inhabitants of Shkodër speak a distinctive dialect of northwestern Gheg Albanian that differs from other Albanian dialects.[75] Shkodër has also a long tradition in the development of the urban music of Albania, marked by a characteristic use of instrumentation and a style of composition.[76]

Rozafa Castle has played an instrumental role in Shkodër's history as the residence of Illyrian monarchs and a military stronghold.[77] Located in the south of Shkodër, its foundations are associated with a legend about a woman who sacrificed herself so the castle could be constructed.[77][78] Historical Museum of Shkodër is the most important museum in Shkodër and was founded to protect artefacts from all over the region of Shkodër, thus displaying their cultural and historical value.[3][79] It is housed inside a monumental mansion from the 19th century, collectively known as the house of Oso Kuka.[3] The expanded Marubi National Museum of Photography located on the Kolë Idromeno Street displays an extensive visual collection of Albanian social, cultural and political life beginning from 1850 on its galleries.[3][80][81]

Shkodër's architecture and urban development are historically and culturally significant for northern Albania. It was and is inhabited by many people of different cultures and religions with many of them leaving mark of their cultural heritage. The Ebu Beker Mosque, Fatih Sultan Mehmet Mosque, Franciscan Church, Lead Mosque, Nativity Cathedral and St. Stephen's Cathedral are the most eminent religious buildings of Shkodër. Other major monuments include the Drisht Castle, Mesi Bridge and ruins of Shurdhah Island.

The Vllaznia club is a professional Albanian football team dedicated to Shkodër. It is one of the most well-known teams in Albania.

The electronic music duo Shkodra Elektronike takes its name from the city of Shkodër. They represented Albania at the Eurovision Song Contest 2025 with the song "Zjerm" finishing in 8th place. The city is the hometown of both members.[82]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The municipality of Shkodër consists of the administrative units of Ana e Malit, Bërdicë, Dajç, Guri i Zi, Postribë, Pult, Rrethinat, Shalë, Shosh, Velipojë and Shkodër.[59][72] The population of the municipality results from the sum of the listed administrative units in the former as of the 2011 Albanian census.[71]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Pasaporta e Bashkisë Shkodër" (in Albanian). Porta Vendore. Archived from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Bashkia Shkoder". Albanian Association of Municipalities (AAM). Archived from the original on 12 October 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Profili i Bashkisë Shkodër" (PDF) (in Albanian). Bashkia Shkodër. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ "The urban population Shkodër – 2011 Census Data (Knoema)". Knoema. Retrieved 20 April 2025.

- ^ "The metro population of Shkodër". Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ a b "Census of Population and Housing". Institute of Statistics Albania.

- ^ "Shkodër". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. n.d. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Galaty, Michael L.; Bejko, Lorenc, eds. (2023). Archaeological Investigations in a Northern Albanian Province: Results of the Projekti Arkeologjik i Shkodrës (PASH): Volume One: Survey and Excavation Results. Memoirs Series. Vol. 64. University of Michigan Press. pp. 69–70, 50, 53. ISBN 9781951538736.

- ^ Sedlar 2013, p. 111.

- ^ a b Rustja, Dritan; Laçi, Sabri. "Hapësira Periurbane e Shkodrës: Përdorimi i Territorit dhe Veçoritë e Zhvillimit Social-Ekonomik" (PDF) (in Albanian). University of Tirana (UT). p. 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 January 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ a b Tafilica, Baze & Lafe 2023, p. 70.

- ^ De Angelis, Daniela, ed. (2014). "Scutari". Oppo e 3 ricerche su Pomezia. Gangemi. ISBN 9788849228823. Archived from the original on 2023-09-23. Retrieved 2020-11-15.

Scutari fu fondata intorno al V-IV secolo a.C. Dagli scavi archeologici eseguiti al castello di Rozafa, si dedusse che il centro era già abitato dall'età del bronzo

- ^ Shpuza, Saimir; Dyczek, Piotr (2015). "Scodra, de la capitale du Royaume Illyrien à la capitale de la province romaine". In Jean-Luc Lamboley; Luan Përzhita; Altin Skenderaj (eds.). L'Illyrie Méridionale et l'Épire dans l'Antiquité – VI (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Diffusion De Boccard. p. 269. ISBN 978-9928-4517-1-2.

- ^ "THE SOCIAL AND CULTURAL IMPACTS OF TOURISM, A CASE OF SHKODRA, ALBANIA" (PDF). University of Shkodra. p. 1. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Battles of the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Chronological Compendium of 667 Battles to 31Bc, from the Historians of the Ancient World (Greenhill Historic Series) by John Drogo Montagu, ISBN 1-85367-389-7, 2000, page 47

- ^ Krahe, Hans (1925). Die alten balkanillyrischen geographischen Namen auf Grund von Autoren und Inschriften. Heidelberg. p. 36.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ e.g. Ptolemy, Geographia II.16.; Polybius, Histories, XXVII.8.

- ^ Wilkes, John (1992). The Illyrians. Wiley. pp. 177–179. ISBN 0-631-19807-5.

- ^ a b Matzinger 2009a, pp. 22–24; Albanian translation: Matzinger 2009b, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Poruciuc, Adrian (1998). Confluențe și etimologii. Polirom. p. 120. ISBN 9789736830402.

- ^ Cabej, Eqrem (1974). "Die Frage nach dem Entstehungsgebiet der albanischen Sprache". Zeitschrift für Balkanologie. 1012: 7–32.; cited after Matzinger 2009.

- ^ a b Demiraj, Shaban (1999). Prejardhja e shqiptarëve nën dritën e dëshmive të gjuhës shqipe. Tirana. pp. 143–144.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link); cited after Matzinger 2009. - ^ Lafe 2022, pp. 362–363, 366.

- ^ Lafe 2022, pp. 362–363, 366–368.

- ^ Matzinger 2009b, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Curtis, Matthew Cowan (2012). Slavic-Albanian Language Contact, Convergence, and Coexistence (Thesis). The Ohio State University. p. 17. Archived from the original on 2023-02-07. Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- ^ Origins: Serbs, Albanians and Vlachs Chapter 2 in Noel Malcolm's Kosovo, a short history (Macmilan, London, 1998, p. 22-40) - The evidence is in fact very mixed; some of the Albanian forms (of both urban and rural names) suggest transmission via Slav, but others -including the towns of Shkodra, Drisht, Lezha, Shkup (Skopje) and perhaps Shtip (Stip, south-east of Skopje) - follow the pattern of continuous Albanian development from the Latin. [48] (One common objection to this argument, claiming that 'sc-' in Latin should have turned into 'h-', not 'shk-' in Albanian, rests on a chronological error, and can be disregarded.) [49] There are also some fairly convincing derivations of Slav names for rivers in northern Albania - particularly the Bojana (Alb.: Buena) and the Drim (Alb.: Drin) - which suggest that the Slavs must have acquired their names from the Albanian forms. [50

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition (1911), "Scutari" article.

- ^ Tafilica, Baze & Lafe 2023, p. 68.

- ^ a b Tafilica, Baze & Lafe 2023, p. 69.

- ^ Polybius

- ^ Titus Livius

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica 2002 page 680

- ^ The Illyrians by John Wilkes, ISBN 0-631-19807-5, 1992, page 172, "...Gentius among the Labeates around Scodra..."

- ^ The Illyrians by John Wilkes, page 213, "The list of Roman settlements includes some of the... Scodra..."

- ^ Rrota, Justin (2010) [1963]. Ditët e mbrame të Turqisë në Shkodër ase Rrethimi i Qytetit 1912-1913. Shkodër: Botime Françeskane. p. 21. ISBN 9789995678371.

- ^ Koti 2006, para. 1, 2

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 206

- ^ Fine, John V. A.; Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. p. 104. ISBN 0472082604.

- ^ Miladin Stevanović; Vuk Branković (srpski velmoža.) (2004). Vuk Branković. Knjiga-komerc. p. 38. ISBN 9788677120382. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

После битке код Велбужда млади краљ Душан, чији је углед знатно порастао, добио је од оца на управљање Зету са седиштем у Скадру.

- ^ Jović, Momir (1994). Srbija i Rimokatolička crkva u srednjem veku. Bagdala. p. 102. ISBN 9788670871045. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

Краљ је у јануару 1331. г. разорио Душанов двор на реци Дримац, код Скадра. Половином априла долази до примирја

- ^ Nikolić, Dejan (1996). Svi vladari Srbije. Narodna biblioteka "Resavska škola". p. 102. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

Стефан Душан је августа 1331. крен- уо са својом војском из Скадра и дошао до Стефановог дворца у Неродимљу, где је изненадио оца. Краљ Стефан је једва успео да побегне из свог дворца у град Петрич у коме га је Душанова војска опколила

- ^ (Albania), Shkodër (2010). Statutet e Shkodrës : në gjysmën e parë të shekullit XIV me shtesat deri më 1469 = Statuti di Scutari della prima metà del secolo XIV con le addizioni fino al 1469. Shtëpia Botuese Onufri. ISBN 978-99956-87-36-6. OCLC 723724243.

- ^ Clayer, Nathalie. " Is̲h̲ḳodra." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Brill Online, 2012. Reference. 2 January 2012 <http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/ishkodra-SIM_8713>

- ^ Elsie, Robert (ed.). "Albania in the Painting of Edward Lear (1848)". albanianart.net.

- ^ "Gjush Sheldija (1902 - 1976) Kryeipeshkvia Metropolitane e Shkodrës dhe Dioqezat Sufragane (shënime)" (PDF).

- ^ Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. pp. 29, 217. ISBN 9781845112875.

- ^ Twenty Years of Balkan Tangle: M. Edith Durham

- ^ Vlora, Eqrem bej (2003). Kujtime 1885-1925. Tiranë: IDK. p. 456. ISBN 99927-780-6-7.

- ^ Juka, Gëzim H. (2018). Shkodranët e 7 prillit dhe të 29 nëntorit. Tiranë: Reklama. pp. 20, 22. ISBN 9789928440358.

- ^ Tomes, Jason (2003). King Zog of Albania : Europe's Self-Made Muslim Monarch. New York, NY: New York University Press. pp. 100–233. ISBN 0-8147-8283-3.

- ^ "Nato joins Albania rescue effort after Balkan floods". BBC News. 6 December 2010.

- ^ Ramsar (August 4, 2010). "The list of wetlands of international importance" (PDF) (in English and Spanish). Ramsar. p. 5. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- ^ Pešić V. & Glöer P. (2013). "A new freshwater snail genus (Hydrobiidae, Gastropoda) from Montenegro, with a discussion on gastropod diversity and endemism in Skadar Lake". ZooKeys 281: 69-90. doi:10.3897/zookeys.281.4409

- ^ "Bashkia e Shkodrës" (PDF). flag-al.org (in Albanian). p. 28.

- ^ "Shkodër (13622) - WMO Weather Station". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ "moyennes 1991/2020".

- ^ "STATION SHKODRA".

- ^ a b "A new Urban–Rural Classification of Albanian Population" (PDF). Instituti i Statistikës (INSTAT). May 2014. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "Law nr. 115/2014" (PDF) (in Albanian). pp. 6374–6375. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Partnerski gradovi". cetinje.me (in Montenegrin). Cetinje. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "Gradovi prijatelji". knin.hr (in Croatian). Knin. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "Binjakëzim mes Shkodrës dhe qytetit Pec në Hungari". ata.gov.al (in Albanian). Agjencia Telegrafike Shqiptare. 2018-10-12. Archived from the original on 2020-11-13. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "Kardeş Şehirler". uskudar.bel.tr (in Turkish). Üsküdar. Retrieved 2020-02-11.

- ^ "Zeytinburnu Belediyesi Yurt Dışı Kardeş Belediyeleri". zeytinburnu.istanbul (in Turkish). Zeytinburnu. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "Welcome to World Bank Intranet" (PDF).

- ^ "Economy".

- ^ Hemming, Andreas; Kera, Gentiana; Pandelejmoni, Enriketa (2012). Albania: Family, Society and Culture in the 20th Century. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 51. ISBN 9783643501448. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ Pandelejmoni, Enriketa (30 November 2021). Shkodra Family and Urban Life (1918 - 1939). LIT Verlag. pp. 76–77. ISBN 9783643910172. Retrieved 16 September 2021.

- ^ "Cities of Albania".

- ^ a b c Nurja, Ines. "Censusi i popullsisë dhe banesave/ Population and Housing Census–Shkodër (2011)" (PDF). Tirana: Institute of Statistics (INSTAT). p. 85. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ "Law nr. 115/2014" (PDF) (in Albanian). Fletorja Zyrtare e Republikës së Shqipërisë. p. 98. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Norris, H. T (1993). Islam in the Balkans: Religion and Society Between Europe and the Arab World. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. p. 76. ISBN 0-87249-977-4. Retrieved 2016-05-12.

- ^ Otten, Karl; Otten, Ellen (1989). Die Reise durch Albanien und andere Prosa. Arche Verlag. p. 175. ISBN 978-3716020852. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ Elsie, Robert. "Albanian Dialects: Introduction". Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ Shetuni, Spiro J. "Albanian Traditional Music An Introduction, with Sheet Music and Lyrics for 48 Songs" (PDF). McFarland & Company. p. 6263. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Rozafa Fortress". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ In Her Footsteps. Lonely Planet Global Limited. February 2020. ISBN 978-1838690670. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ "The Museum: History". Historical Museum of Shkodër. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ "About us". Marubi National Museum of Photography. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ "Marubi National Photography Museum". Lonely Planet. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ^ "Albania: Shkodra Elektronike to Eurovision 2025 with "Zjerm"". Eurovisionworld. 2024-12-23. Retrieved 2025-05-14.

Bibliography

[edit]- Wilkes, John (9 January 1996). The Illyrians. Wiley. ISBN 9780631198079. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Piotr Dyczek; Krzysztof Jakubiak; Adam Lajtar, eds. (2020). "Rhizon–capital of the Illyrian kingdom–some remarks". Ex Oriente Lux. Studies in Honour of Jolanta Młynarczyk. University of Warsaw Press. pp. 423–433.

- John Van Antwerp Fine Jr. (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472081493. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Koti, Isidor. "Celebration of Saint John Vladimir in Elbasan". Orthodox Autocephalous Church of Albania. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Lafe, Genc (2022). "I rapporti tra toponimi e voci ereditate dell'albanese sulla base dell'analisi della loro evoluzione fonetica". In Shaban Sinani; Francesco Altimari; Matteo Mandalà (eds.). Albanologu i arvanitëve "Atje kam u shpirtin tim...". Academy of Sciences of Albania. pp. 355–370. ISBN 978-9928-339-74-4.

- Matzinger, Joachim (2009a). "Die Albaner als Nachkommen der Illyrer aus der Sicht der historischen Sprachwissenschaft". In Schmitt, Oliver Jens; Frantz, Eva Anne (eds.). Albanische Geschichte: Stand und Perspektiven der Forschung (in German). Munich: Oldenbourg.

- Matzinger, Joachim (2009b). "Shqiptarët si pasardhës të ilirëve nga këndvështrimi i gjuhësisë historike". In Schmitt, Oliver Jens; Frantz, Eva Anne (eds.). Historia e Shqiptarëve: Gjendja dhe perspektivat e studimeve (in Albanian). Translated by Pandeli Pani and Artan Puto. Botime Përpjekja. ISBN 978-99943-0-254-3.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (2013). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295800646.

- Shpuza, Saimir (2014). Dyczek, Piotr (ed.). "Iron Age Fortifications and the Origin of the City in the Territory of Scodra". Novensia. 25. Warszawa: Ośrodek Badań nad Antykiem Europy Południowo-Wschodniej: 105–126. ISBN 978-83-934239-96. ISSN 0860-5777.

- Shpuza, Saimir; Dyczek, Piotr (2015). "Scodra, de la capitale du Royaume Illyrien à la capitale de la province romaine". In Jean-Luc Lamboley; Luan Përzhita; Altin Skenderaj (eds.). L'Illyrie Méridionale et l'Épire dans l'Antiquité – VI (in French). Vol. 1. Paris: Diffusion De Boccard. pp. 269–278. ISBN 978-9928-4517-1-2.

- Shpuza, Saimir (2017). Dyczek, Piotr (ed.). "Scodra and the Labeates. Cities, rural fortifications and territorial defense in the Hellenistic period". Novensia. 28. Warszawa: Ośrodek Badań nad Antykiem Europy Południowo-Wschodniej: 41–64. ISBN 978-83-946222-5-1. ISSN 0860-5777.

- Tafilica, Zamir; Baze, Ermal; Lafe, Ols (2023). "Historical Background". In Galaty, Michael L.; Bejko, Lorenc (eds.). Archaeological Investigations in a Northern Albanian Province: Results of the Projekti Arkeologjik i Shkodrës (PASH): Volume One: Survey and Excavation Results. Memoirs Series. Vol. 64. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9781951538736.

External links

[edit]- bashkiashkoder.gov.al – Official Website (in Albanian)