Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

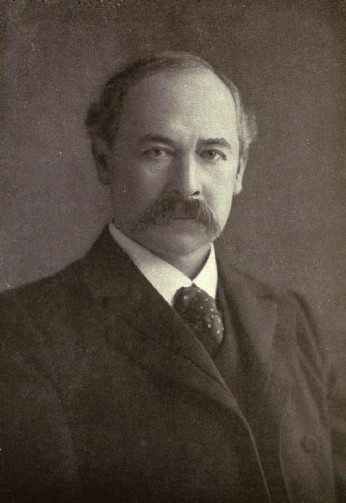

Silvanus P. Thompson

View on Wikipedia

Silvanus Phillips Thompson FRS (19 June 1851 – 12 June 1916) was an English professor of physics at the City and Guilds Technical College in Finsbury, England. He was elected to the Royal Society in 1891 and was known for his work as an electrical engineer and as an author. Thompson's most enduring publication is his 1910 text Calculus Made Easy, which teaches the fundamentals of infinitesimal calculus, and is still in print.[2] Thompson also wrote a popular physics text, Elementary Lessons in Electricity and Magnetism,[3] as well as biographies of Lord Kelvin and Michael Faraday.

Key Information

Biography

[edit]Thompson was born on 19 June 1851 to a Quaker family in York, England. His father served as a master at the Quaker Bootham School[4] in York and he also studied there. In 1873 Silvanus Thompson was made the science master at the school. He graduated and sat for Bachelor of Arts University of London external degree in 1869.[5] After a teaching apprenticeship he was awarded a scholarship to the Royal School of Mines (RSM) in South Kensington, where he studied chemistry and physics. He graduated with honors with a Bachelor of Science degree and started working at RSM. He soon became a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical and Physical Society; he participated in meetings—lectures with demonstrations of experiments organized at the Royal Institution.

On 11 February 1876 he heard Sir William Crookes give an evening discourse at the Royal Institution on The Mechanical Action of Light when Crookes demonstrated his light mill or radiometer. Thompson was intrigued and stimulated and developed a major interest in light and optics (his other main interest being electromagnetism). In 1876 he was appointed as a lecturer in physics at University College, Bristol, and later was made Professor in 1878 at the age of 27. He had received a D.Sc. from the University of London in 1878.[6]

A major concern of Thompson was the area of technical education and he made a series of continental tours to France, Germany and Switzerland to compare the continental approach to that in the UK. In 1879 he gave a paper at the Royal Society of Arts on Apprenticeship, Scientific and Unscientific in which he detailed the deficiencies in technical education in England. In the discussion, the opinion was expressed that England was too conservative to make use of trade schools and that continental methods would not be applicable in the UK. Thompson recognised that technical education was the means by which scientific knowledge could be put into action and spent the rest of his life putting his vision into practical realisation.

In 1878 the City and Guilds of London Institute for the Advancement of Technical Education was founded. Finsbury Technical College was a teaching institution created by the City and Guilds Institute and it was as its Principal and Professor of Physics that Thompson was to devote the next 30 years.

Thompson's particular gift was in his ability to communicate difficult scientific concepts in a clear and interesting manner. He attended and lectured at the Royal Institution giving the Christmas lectures in 1896 on Light, Visible and Invisible with an account of Röntgen Light. He was an impressive lecturer and the radiologist AE Barclay said that: "None who heard him could forget the vividness of the word-pictures he placed before them".

In 1891 Thompson developed the idea of a telegraph submarine cable that could increase the distance of the electrical pulse and therefore increase the speed of transmitting words across the telegraph cable. Until then there was an average speed of between 10 and 50 words per minute but his design was to counteract the discharging of electrical energy across the cable by introducing a return earth as part of the internal electrical structure of the cable (something like coaxial cable today). His idea, written about by Charles Bright in his book "Submarine Telegraphs", discusses the idea that the two wires could be designed as separate conductors but along their path they would be connected by an induction coil. This would allow for the introduction of capacitance and therefore allow for the distance of the electrical charge to increase so increasing the word count. This was a design that would help revolutionise submarine telegraphy and the future of telephone submarine systems.

Thompson repeated Röntgen's experiments on the day after the discovery was announced in the UK and following this gave the first public demonstration of the new rays at the Clinical Society of London on 30 March 1896. William Hale-White said: "The audience was thrilled, most seeing for the first time actual pieces of bones and metal. Silvanus Thompson was a prince among lecturers. I have never heard a better demonstration or attended a more memorable medical meeting".

He was the first President of the Röntgen Society (later to become the British Institute of Radiology).[9][10] He described the society as being between medicine, physics and photography. It was his genius that put its stamp on that society and has made it into the rich amalgam of medical, scientific and technical members that it is today. As he said in his presidential address to the Röntgen Society: "The pioneers have opened the way into the wilderness; they are now being followed by those who will occupy the new territory, complete its survey, and map out its features. Not until every corner is explored and charted will the work of our Society be ended".

In 1900 Thompson was involved in the controversial Whitehall attack on Marconi's patents, when the Post Office commissioned both him and Professor Oliver Lodge to produce secret reports. The purpose was either to declare the Marconi Company patents invalid, or to produce similar, but technically different equipment: the latter involved Thompson. When the Admiralty received the two reports it was the pioneer of wireless telegraphy Captain (later, Admiral Sir) Henry Jackson, then commanding HMS Vulcan, whose opinion led a senior naval officer to report, "it would be unworthy to try to evade the Marconi Company's patent."

Thompson was committed to truth in all aspects and his 1915 Swarthmore Lecture delivered to the Society of Friends was The Quest for Truth, indicating his belief in truth and integrity in all aspects of our lives. Thompson remained an active member of the Religious Society of Friends, throughout his life[11]

He died in London, after a short illness, on 12 June 1916, leaving a widow and four daughters.[12][13]

Literary works

[edit]

Thompson wrote many books of a technical nature particularly Elementary Lessons in Electricity & Magnetism (1881[14]), Dynamo-electric Machinery (1884) and the classic Calculus Made Easy which was first published in 1910, and is still in print.

Thompson had many interests including painting, literature, the history of science, and working in his greenhouse. He wrote biographies of Michael Faraday and Lord Kelvin. He also wrote about William Gilbert, the Elizabethan physician, and produced an edition of Gilbert's De Magnete at the Chiswick Press in 1900. In 1912, Thompson published the first English translation of Treatise on Light by Christiaan Huygens.

His scientific library of historical and working books is preserved at the Institution of Electrical Engineers and is a wonderful collection (he was President of the IEE). It includes many classic books on electricity, magnetism and optics. The collection consists of 900 rare books and 2500 nineteenth and early twentieth century titles, with approximately 200 autograph letters.

Editions

[edit]

- Dynamo-electric machinery (in French). Paris: Baudry. 1886.

- Polyphase electric currents and alternate-current motors (in French). Paris: Béranger. 1901.

Lectures

[edit]Thompson lectured at the Royal Institution giving the Christmas lectures in 1896 on Light, Visible and Invisible with an account of Röntgen Light.

In 1910 Thompson was invited to deliver the Royal Institution Christmas Lecture on Sound: Musical and Non-Musical.

Honours

[edit]- Thompson is one of the individuals represented on the Engineers Walk in Bristol, England.

- Thompson was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on 14 May 1891[12] and was elected a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1894. In 1902, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[15]

Inventions

[edit]Thompson invented the permeameter.[16]

In London, in 1910, Thompson was involved in early attempts to stimulate the brain using a magnetic field. Many years after his death the technique would eventually become refined as Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ Thompson's obituary in Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 1917–1918, vol. 94, pp xvi–xix. See also Silvanus Thompson, His Life and Letters, Unwin, London, 1920 by Thompson and Thompson

- ^ The original version is now in the public domain. A new edition has been updated and edited by Martin Gardner.

- ^ Silvanus Phillips Thompson, radiology and the Röntgen Society by Adrian M K Thomas, British Society for the History of Radiology, Department of Radiology, Princess Royal University Hospital, Orpington, Kent BR6 8ND

- ^ Bootham Old Scholars Association (2011). Bootham School Register. York, England: BOSA.

- ^ Basu, S. K. (2006). Encyclopaedic biography of the world great physicists. Global Vision Pub House. ISBN 9788182201569.

- ^ "Silvanus Phillips Thompson | Electricity, Magnetism, Telegraphy | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. 11 April 2024. Retrieved 30 May 2024.

- ^ Photograph from Thompson and Thompson (1920), Silvanus Thompson, His Life and Letters, London: Unwin.

- ^ Photograph from Thompson and Thompson (1920), Silvanus Thompson, His Life and Letters, London: Unwin

- ^ "AIM25 collection description". Aim25.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ "British Institute of Radiology homepage – British Institute of Radiology". Bir.org.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article by Arthur Smithells, 'Thompson, Silvanus Phillips (1851–1916)’, revised by Graeme J. N. Gooday, online edn, May 2006 [1], accessed 8 December 2006

- ^ a b "Obituary notice, Fellow: Thompson, Silvanus Phillips". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 77: 305. 1917. Bibcode:1917MNRAS..77..305.. doi:10.1093/mnras/77.4.305.

- ^ "Silvanus Thompson – British Institute of Radiology".

- ^ "Elementary Lessons in Electricity & Magnetism". Macmillan. 1881.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Anthony T. Barker and Ian Freeston (2007). "Transcranial magnetic stimulation". Scholarpedia. 2 (10). scholarpedia.org: 2936. Bibcode:2007SchpJ...2.2936B. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.2936.

Further reading

[edit]Sorted by date.

- Bright, C. "Submarine Telegraphs", C. Lockwood, London, 1898.

- Obituary in Proceedings of the Royal Society A, 1917–1918, vol. 94, pp xvi–xix

- Obituary in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 1917, vol. 77, pp 305–307 – Online at ADS

- Thompson, Jane Smeal and Thompson, Helen G., Silvanus Phillips Thompson: His Life and Letters (London: T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd., 1920). Also available as the (New York: E. P. Dutton and Company, 1920) printing. Additional different scannings of this book are available at the Internet Archive.

- Lynch, A. C., "Silvanus Thompson: teacher, researcher, historian," IEE Proceedings, 1989, vol. 136, A(6), pp 306–312.

- Gay, H. and Barrett, A., "Should the Cobbler Stick to his Last? Silvanus Phillips Thompson and the Making of a Scientific Career," British Journal for the History of Science, 2002, vol. 35, 151–86

- Shipley, Brian C. (August 2003). "Gilbert, Translated: Silvanus P. Thompson, the Gilbert Club, and the Tercentenary Edition of De Magnete". Canadian Journal of History. 38 (2): 259–280. doi:10.3138/cjh.38.2.259. Archived from the original on 22 November 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- Claus Bernet (2011). "Silvanus P. Thompson". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 32. Nordhausen: Bautz. cols. 1420–1428. ISBN 978-3-88309-615-5.

External links

[edit]- Works by Silvanus P. Thompson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Silvanus P. Thompson at the Internet Archive

- Works by Silvanus P. Thompson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Silvanus P. Thompson

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Birth and Family Background

Silvanus Phillips Thompson was born on 19 June 1851 in York, England, into a devout Quaker family known for its commitment to education and moral principles.[1] His father, also named Silvanus Thompson, served as a schoolmaster at the Quaker Bootham School in York and as a minister within the Society of Friends, roles that underscored the family's dedication to teaching and spiritual guidance.[1][6] Thompson's mother, Bridget Tatham, came from a Quaker family in Settle, Yorkshire, and brought her own intellectual interests to the household, particularly in botany, which contributed to the nurturing environment for scientific curiosity.[6][4] As the second of eight children, Thompson grew up in a close-knit family that emphasized Quaker tenets such as pacifism, simplicity, and the pursuit of knowledge as a form of spiritual discipline.[1] The household reflected the Society of Friends' values through modest living and a rejection of militarism, shaping Thompson's lifelong aversion to conflict and his focus on peaceful applications of science.[7] Intellectual discussions were central to family life, with his father's mathematical teaching and mother's botanical expertise fostering an atmosphere where learning was both a duty and a joy.[4] This environment, rooted in the Quaker tradition of equality and inquiry, provided Thompson with early models of integrating faith with rational thought.[7] Thompson's initial exposure to science occurred within this familial and communal setting, through conversations at home and during Quaker meetings where ethical and natural world topics were explored.[4] His grandfather's background as a chemist and great-uncles' as Fellows of the Royal Society further enriched these interactions, sparking Thompson's interest in empirical observation long before formal schooling.[4] Such influences from his Quaker upbringing laid the groundwork for his later scientific endeavors, blending moral simplicity with a methodical approach to discovery.[7]Formal Education and Early Influences

Silvanus Phillips Thompson, raised in a Quaker family that emphasized intellectual and moral development, began his formal education at Bootham School, a Quaker institution in York, in 1863. Under the guidance of his father, who served as a mathematics and botany master there, Thompson excelled in his studies and cultivated a strong interest in mathematics and natural history.[8] During his time at Bootham, he also displayed an early fascination with electricity, contributing an article on the subject to the school's magazine, which marked the beginning of his engagement with scientific experimentation.[7] In 1867, Thompson entered the Flounders Institute at Ackworth, a training school for Quaker teachers near Pontefract, where he prepared for a career in education while pursuing external studies with the University of London. He earned his B.A. from the University of London in 1869, followed by a return to Bootham as a junior master in 1870 and science master from 1873 to 1875.[8] These years solidified his teaching skills and allowed him to conduct initial student projects on magnetism, including hands-on experiments that explored magnetic fields and their properties.[7] Securing a scholarship in 1875, Thompson enrolled at the Royal School of Mines in London, where he studied chemistry and physics for a year under influential professors such as Thomas Henry Huxley, Frederick Guthrie, and Edward Frankland.[8] In 1876, he attended lectures at Heidelberg University for one semester, studying under Robert Bunsen and August Kundt.[8][6] Huxley's lectures on biology and natural philosophy, in particular, shaped Thompson's interdisciplinary approach to science, while his own early experiments in electricity during this period built on schoolboy interests and foreshadowed his later expertise. He completed his B.Sc. from the University of London in 1875 with first-class honors in physics and chemistry, and later obtained his D.Sc. in 1878, capping his formal academic training.[8][6][9]Academic and Professional Career

Teaching and Research Positions

Thompson began his academic career in 1876 when he was appointed as a lecturer in physics at the newly established University College, Bristol.[10] He advanced quickly, earning his D.Sc. from the University of London in 1878 and being elected professor of physics at the same institution that year, a role he held until 1885.[11] During this period, Thompson emphasized practical teaching methods in physics and engineering, preparing students for technical professions while laying the groundwork for his own research interests in electricity.[1] In 1885, Thompson moved to London as principal and professor of physics at the City and Guilds Technical College in Finsbury, where he served as head of the physics department until his death in 1916.[2] Under his leadership, the department became a leading center for electrical engineering education, training students in applied sciences and fostering hands-on experimentation with electrical apparatus.[4] His tenure at Finsbury allowed him to integrate teaching with research, emphasizing the practical applications of physics in industry. Thompson's research during these positions centered on electromagnetic theory, with significant work on alternating currents and their practical implementation. He authored influential texts, such as Polyphase Electric Currents and Alternate-Current Motors (1895), which detailed the principles and design of AC systems, contributing to their adoption in power transmission.[12] Additionally, he advanced submarine cable technology by proposing in 1891 the use of distributed electromagnetic induction to counteract electrostatic capacity, enabling longer-distance signal transmission in telegraph cables.[13] Thompson also collaborated with institutions like the Royal Society, where he was elected a Fellow in 1891 and presented numerous papers on electrical and magnetic phenomena, supporting efforts to establish technical standards in electrotechnology.[14]Administrative and Institutional Roles

In 1885, Silvanus P. Thompson was appointed Principal and Professor of Physics (later Electrical Engineering) at the City and Guilds Technical College, Finsbury, a position he held until his death in 1916, during which he oversaw significant reforms in technical education.[15][1] Under his leadership, the college emphasized practical, hands-on training in applied sciences, integrating laboratory work with theoretical instruction to prepare students for industrial roles, thereby advancing vocational science education in Britain.[16][5] Finsbury became a pioneering model for such institutions, influencing the structure of technical colleges by demonstrating the value of specialized curricula in electricity, mechanics, and engineering for the emerging industrial workforce.[16] Thompson played a key role in international efforts to standardize electrical units through his participation in the International Electrical Congresses. As a British delegate to the 1893 Chicago Congress, he presented on advancements in ocean telephony and contributed to discussions on uniform measurement standards for resistance, current, and potential, helping align global practices in electrical engineering.[8][17] His involvement extended to later events, including serving as honorary vice-president of the 1911 Electrotechnical Congress in Turin, where further refinements to international units were debated and adopted.[1] Throughout the 1890s and 1910s, Thompson held advisory positions on multiple government committees addressing telegraphy, electrical standards, and engineering policy, providing expert input on technical specifications and regulatory frameworks to support Britain's telecommunications and industrial infrastructure.[7] These roles underscored his influence on national policy, bridging academic research with practical governmental needs in an era of rapid technological expansion.[7]Scientific Contributions

Advances in Electricity and Magnetism

Silvanus P. Thompson made significant theoretical and experimental contributions to electromagnetism, particularly through his detailed investigations into the behavior of iron under magnetic influence. In his 1891 treatise The Electromagnet and Electromagnetic Mechanism, Thompson outlined methods for measuring magnetic permeability and hysteresis, emphasizing their practical importance for designing efficient electromagnetic devices. He described the ring method for inductive measurements, where the magnetizing force is calculated as , with as the sectional area, the current, and the mean length of the magnetic path, allowing precise determination of permeability as the ratio of magnetic induction to .[18] These techniques built on earlier work by Rowland and Ewing, enabling quantitative assessment of iron's response to varying magnetizing forces, such as in dynamo armatures where high permeability minimizes energy loss.[18] Hysteresis, the lag in magnetization that causes energy dissipation as heat, was a central focus of Thompson's experiments, illustrated through B-H loops where the enclosed area quantifies the work lost per cycle. He explained this phenomenon using Ewing's molecular theory, attributing it to the rotation and alignment of atomic magnets in iron, rather than frictional models, and provided data showing residual magnetism in wrought iron reaching approximately 47,000 lines per square inch after demagnetization.[18] Thompson's traction method measured coercive force by quantifying the pull between magnetized surfaces via , verified experimentally with Bosanquet's lever and ballistic galvanometer setup, highlighting hysteresis's role in limiting rapid reversals in alternating-current applications.[18] These studies underscored the need for annealed soft iron to reduce hysteresis losses, influencing the design of electromagnets and transformers. A cornerstone of Thompson's theoretical framework was the equation for magnetic flux density, , where represents lines of magnetic induction per unit area, the magnetizing force, and the permeability specific to the medium. Derived from analogies to electric circuits—treating magnetic flux as analogous to current and reluctance as resistance—Thompson formalized it within the C.G.S. system, drawing on Faraday's induction laws and Rowland's 1873 circuit principles.[18] Historically, this relation evolved from Gilbert's early observations of terrestrial magnetism and Coulomb's force laws, but Thompson provided a comprehensive explanation in the context of saturated materials, noting that peaks at around 1,400 for iron at 12,000 lines/cm² before declining due to saturation.[18] He illustrated its application in calculating flux through air gaps, where the pull on an armature is proportional to , essential for relay and motor mechanisms. In the 1890s, Thompson extended his research to polyphase currents and alternating-current motors, publishing Polyphase Electric Currents and Alternate-Current Motors in 1895, which synthesized European and American developments for practical engineering use. The work detailed the production of rotating magnetic fields using two-phase or three-phase systems, enabling efficient induction motors without commutators, and included Tesla's contributions on interplanetary communication as an appendix. Thompson emphasized the advantages of polyphase distribution for power transmission, reducing copper losses compared to single-phase systems, and provided vector diagrams for phase relationships, influencing the adoption of AC technology in Britain. Thompson's contributions to submarine telegraphy addressed key challenges in long-distance signaling, particularly insulation integrity for transatlantic cables. In 1891, he patented a design using dual conductors connected via induction coils to extend pulse range and enhance transmission speed, mitigating attenuation in underwater environments.[8] His methods for insulation testing involved capacitive and resistive measurements to detect faults, drawing from Kelvin's galvanometer techniques but adapted for high-voltage gutta-percha coatings on Atlantic cables, ensuring reliable conductivity over thousands of miles.[8] These innovations improved cable reliability, supporting the expansion of global telegraph networks in the late 19th century.Work on X-rays and Radiology

Silvanus P. Thompson played a pivotal role in introducing X-rays to Britain shortly after Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen's discovery in late 1895. Leveraging his extensive prior knowledge of electricity and high-voltage phenomena, Thompson successfully replicated Röntgen's experiments within days of the news reaching London and conducted one of the earliest public demonstrations in March 1896 at the Clinical Society of London. He further popularized X-rays through his Royal Institution Christmas Lectures in December 1896, titled Light, Visible and Invisible, which included demonstrations using a Crookes tube and a fluorescent screen to showcase the penetration of X-rays through soft tissues to reveal bone structures, captivating audiences and sparking widespread interest in the new technology's potential for medical diagnostics.[19][20] To foster systematic research and application of X-rays, Thompson served as the first president of the Röntgen Society (initially the X-ray Society), founded in 1897 after a meeting called by Dr. David Walsh. The society, established on April 2, 1897, in London, aimed to bridge physics, medicine, and engineering by promoting studies on radiology, standardizing equipment, and sharing findings through meetings and publications like the Archives of the Röntgen Ray. Under Thompson's leadership, the society's first general meeting on June 3, 1897, renamed it the Röntgen Society, and the Grand Inaugural Meeting in November 1897 highlighted practical advancements, solidifying the society's role in advancing radiology as a discipline.[21] Thompson was also among the first to highlight the health risks associated with X-ray exposure, drawing from his own experiments that resulted in skin burns. As early as 1896, he warned of the rays' potential to cause tissue damage, emphasizing the need for protective measures during prolonged use, which influenced early safety protocols in radiology.[22] In terms of technical contributions, Thompson advanced X-ray imaging by adapting photographic techniques, including the use of sensitized plates and Crookes tubes optimized for higher output. He demonstrated methods to increase the power of X-ray tubes, enabling clearer and more reliable radiographs of internal structures, which improved the accessibility of the technology for medical professionals.[22]Key Inventions and Devices

One of Silvanus P. Thompson's most notable inventions was the permeameter, introduced in 1890 as an instrument for measuring the magnetic permeability and induction of iron and other ferromagnetic materials. The device addressed the need for accurate assessment of magnetic properties in materials used for electromagnets and transformers, enabling precise quantification of how effectively a material conducts magnetic flux under varying magnetizing forces. Its design featured a rectangular iron block with reentrant holes at the ends for inserting test samples, positioned between the pole-pieces of an electromagnet; the magnetizing force was calculated from the exciting current and the magnetic circuit's geometry, while magnetic induction was determined by the mechanical pull on the block, measured via a spring balance attached to one end. This apparatus provided a practical, direct method for industrial testing of iron quality, influencing subsequent developments in magnetic measurement tools and finding application in the emerging electrical engineering sector for optimizing dynamo and motor designs. In 1910, Thompson pioneered an early electromagnetic device for brain stimulation, predating modern transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) techniques by inducing currents in neural tissue through rapidly alternating magnetic fields.[23] The setup involved a high-powered electromagnet energized by an alternating current of 50-60 Hz, with the subject's forehead placed near the pole-pieces to expose the brain to fields strong enough to generate eddy currents in conductive tissues.[23] Thompson reported observing faint visual phosphenes—flashes of light—during self-experiments, attributing them to physiological effects on the visual cortex rather than direct retinal stimulation, thus demonstrating the potential for non-invasive neural modulation.[23] This work, inspired by prior observations of magnetophosphenes, laid foundational insights into bioelectromagnetic interactions, though it remained experimental and was not commercialized at the time.[23] Thompson also devised practical demonstration devices for illustrating alternating current (AC) principles, particularly during his lectures on polyphase systems and motors in the 1890s.[12] These included scaled models of induction motors and synchronous machines, constructed with simple windings, rotors, and exciters to visually depict torque production, phase relationships, and power distribution in AC circuits.[12] For instance, his motor models used rotating armatures and multiphase supplies to show self-starting mechanisms without commutators, aiding educational demonstrations at institutions like the City and Guilds Technical College.[12] These tools were instrumental in promoting AC adoption over direct current, as they clarified complex phenomena like rotating magnetic fields for students and engineers.[12] Thompson secured several patents for electrical innovations, reflecting his applied research in telecommunications and power transmission. In 1882, he patented improvements in telephone instruments, enhancing signal clarity through better diaphragm and coil designs amid early telephony disputes.[24] More significantly, his 1891 British patent No. 12,396 described a submarine telegraph cable incorporating induction coils along twin conductors to counteract signal attenuation, effectively introducing distributed loading to extend pulse transmission distances and speeds.[19] This concept anticipated Pupin's later loading coil patents and was adopted in transatlantic cable designs, improving reliability for international telegraphy networks by the early 20th century and influencing industrial standards for long-distance wired communications.[19]Literary Works

Major Scientific Texts

Silvanus P. Thompson's major scientific texts exemplify his commitment to pedagogical clarity and accessibility in mathematics and physics, making complex subjects approachable through intuitive explanations and practical illustrations rather than rote formalism. His works, particularly those on calculus, electricity, and electrical machinery, were designed for students and practitioners, emphasizing conceptual understanding over abstract theory. These textbooks influenced technical education by providing step-by-step guidance that bridged theoretical principles with real-world applications, often incorporating diagrams and examples drawn from engineering contexts.[3] Calculus Made Easy, published in 1910 by Macmillan, stands as Thompson's most renowned contribution to mathematical education, adopting an anti-formulaic approach that prioritizes intuitive reasoning and everyday analogies to demystify infinitesimal calculus. Rather than overwhelming readers with symbolic manipulations, Thompson employs a conversational tone to explain core concepts, such as treating differentials as "little bits" of change (e.g., dx as a tiny increment in x) and rates of change (dy/dx) as slopes on a graph, using relatable scenarios like the growth of a square's area to illustrate how dy/dx neglects higher-order infinitesimals like (dx)^2. The book's structure builds progressively: early chapters (II–IV) introduce differentials through "different degrees of smallness," "relative growings," and "simplest cases" of differentiation, such as y = x^2 yielding dy/dx = 2x; subsequent sections (V–IX) extend this to constants, products, quotients, and successive differentiation; while later chapters (X–XVI) explore geometrical meanings, maxima/minima, and applications like sines and partial differentiation. Integral calculus follows in chapters XVII–XXI, framing integration as the "reverse of differentiating" to accumulate small elements (e.g., ∫dx = x + C), with intuitive examples like summing time increments to find total areas under curves, avoiding heavy reliance on formula memorization. This method fosters deep comprehension, as Thompson warns against "preliminary terrors" of notation in the opening chapter, encouraging readers to grasp why calculus works through trial and analogy.[25][26] In Elementary Lessons in Electricity and Magnetism, first published in 1881 by Macmillan and revised through multiple editions up to 1915, Thompson provides a systematic introduction to electromagnetic principles, progressing from basic notions to advanced field theory with a focus on practical circuits. The text begins with foundational concepts like matter, force, and the "two fluids" theory of electricity, then advances step-by-step through electrostatics (e.g., charges, potentials, and condensers), current electricity (including Ohm's law and resistance networks), magnetism (poles, lines of force), and electromagnetism (induction, transformers). Circuits are explained incrementally, starting with simple batteries and wires, building to complex arrangements like Wheatstone bridges and galvanometers, with detailed derivations for Kirchhoff's laws applied to loop currents. Field theory is introduced intuitively via vector diagrams and scalar potentials, illustrating Faraday's lines of force to visualize magnetic and electric fields around conductors. Abundantly illustrated with over 400 diagrams—such as cross-sections of coils showing induced currents and equipotential maps— the book equips readers to analyze real devices, emphasizing experimentation alongside theory to reinforce understanding.[27][28] Dynamo-Electric Machinery: A Manual for Students of Electrotechnics, issued in two volumes between 1884 and 1888 by Spon (London), offers a comprehensive treatment of electrical generators and motors, tailored for aspiring engineers with both theoretical foundations and practical computations. Volume I (1884) covers dynamo principles, armature reactions, and generator design, deriving equations for electromotive force (e.g., E = B l v for motional EMF) and commutation; Volume II (1888) addresses motors, alternators, and polyphase systems, including efficiency analyses through power balance equations like η = (output power / input power) × 100%, with examples calculating losses from copper resistance, iron hysteresis, and mechanical friction in Siemens and Edison machines. Thompson integrates vector diagrams for phase relations and performance curves to predict efficiency under varying loads, providing worked examples for optimizing armature windings and field excitations. This multi-volume structure allows progressive mastery, from theoretical electromagnetism to design specifications, supported by historical context on inventors like Pacinotti and Hopkinson.[29][30] Thompson's texts had a profound impact on self-taught engineers, serving as self-study resources that democratized technical knowledge during the electrical engineering boom, with Calculus Made Easy particularly valued for its engineer-friendly intuition that bypassed rigorous proofs in favor of applicable insights. Their enduring relevance is evident in continued reprints and adaptations into the 21st century, including digital editions and modern revisions that preserve Thompson's accessible style for contemporary learners.[3][31][26]Biographies and Translations

Silvanus P. Thompson's biographical writings provided intimate portraits of key figures in Victorian science, blending personal narratives with chronological accounts of their scientific achievements. His 1898 biography, Michael Faraday: His Life and Work, published by Cassell and Company, spans 308 pages and draws on Faraday's notebooks, letters, and contemporary reminiscences to chronicle his life from humble beginnings as a bookbinder's apprentice in 1791 to his death in 1867.[32] The work incorporates personal anecdotes, such as Faraday's boyhood speech impediment corrected by his mother's encouragement, his discomforts as valet during travels with Humphry Davy in 1813–1815, his 1821 marriage proposal to Sarah Barnard amid initial hesitation, and his 1835 refusal of a government pension due to a perceived theological slight before later accepting it under public pressure.[32] Scientifically, it outlines a timeline of milestones, including Faraday's 1821 discovery of electromagnetic rotations, his 1831 breakthrough in electromagnetic induction via an iron ring experiment producing a spark, his 1832 Bakerian Lecture on terrestrial magneto-electric induction, and his 1845 explorations of diamagnetism and the magneto-optic effect in heavy glass.[32] In 1910, Thompson published the two-volume The Life of William Thomson, Baron Kelvin of Largs with Macmillan and Company, offering a comprehensive examination of Kelvin's career from his early mathematical training at the University of Glasgow to his later administrative roles and knighthood.[33] Drawing on private correspondence, diaries, and Kelvin's papers, the biography emphasizes his thermodynamic contributions, such as the development of the absolute temperature scale (Kelvin scale) in the 1840s, his formulation of the second law of thermodynamics through work on heat engines, and his applications of thermodynamics to oceanography and geology, including estimates of Earth's age.[34] Thompson highlights Kelvin's interdisciplinary impact, from electrical engineering in transatlantic telegraphy to theoretical physics, portraying him as a bridge between pure science and industrial application during the Victorian era.[34] A significant translational effort was Thompson's 1900 annotated English edition of William Gilbert's 1600 De Magnete, published in a limited run of 250 copies by the Gilbert Club through Chiswick Press, London. This work, which explored magnetism and the Earth's magnetic properties, included Thompson's extensive notes and appendices, making Gilbert's pioneering ideas accessible to English-speaking audiences and contributing to the historical study of electromagnetism.[5] Thompson extended his historical efforts through translations, notably his 1912 annotated English edition of Christiaan Huygens' 1690 Treatise on Light, published by Macmillan & Company, London, and available via Project Gutenberg.[35][36] The translation faithfully renders Huygens' wave theory of light propagation, structured across six chapters covering straight-line rays, reflection, refraction (including in air), the "strange refraction" of Iceland crystal (double refraction), and figures of transparent bodies.[35] Thompson's annotations provide modern context, clarifying Huygens' terminology (e.g., distinguishing "refraction" as process versus result), referencing influences like Erasmus Bartholinus' 1669 observations of double refraction in rock crystal, and contrasting Huygens' longitudinal wave model with later developments by Thomas Young and Augustin Fresnel on transverse vibrations.[35] For instance, in notes on Chapter V, Thompson elucidates Huygens' hypothesis of dual wave emanations for regular and irregular refraction, linking it to geometrical optics principles like Fermat's.[35] Through these works, Thompson played a pivotal role in documenting Victorian science history, preserving primary sources and narratives that illuminated the era's scientific ethos and Quaker-influenced moral frameworks in research.[37] His biographies and translation not only chronicled individual legacies but also contextualized the interplay of experimentation, theory, and societal progress in 19th-century Britain, ensuring accessibility for future scholars.[37]Lectures and Public Engagement

Royal Institution Christmas Lectures

Silvanus P. Thompson delivered his first series of Royal Institution Christmas Lectures in 1896, titled "Light, Visible and Invisible," which captivated young audiences by exploring the nature of light across the electromagnetic spectrum. The lectures featured hands-on demonstrations of spectra using prisms to decompose white light into its colorful components, illustrating the principles of dispersion and refraction in optics. Thompson incorporated X-ray demonstrations shortly after Wilhelm Röntgen's 1895 discovery, showcasing live imaging of objects to reveal invisible rays penetrating matter, thereby linking his own research in radiology to public education. These experiments highlighted the invisible aspects of light, such as ultraviolet and infrared, making abstract concepts tangible through visual spectacles.[20] To engage the juvenile audience, Thompson employed innovative techniques including optical illusions and live models, such as projecting distorted images to demonstrate perceptual tricks and using human subjects in shadow plays to convey light propagation. These methods not only entertained but also fostered curiosity about physics, drawing over 350 attendees per session in the Royal Institution's tiered hall. The series held historical significance in popularizing science amid the excitement following Röntgen's breakthrough, positioning Thompson as a bridge between cutting-edge research and accessible education.[20] In 1910, Thompson returned for another series, "Sound: Musical and Non-Musical," delving into the physics of auditory phenomena with a focus on vibrations, acoustics, and resonance. Demonstrations included vibrating strings and plates to visualize sound waves, acoustic experiments with resonance tubes and tuning forks to show harmonic interactions, and the use of air pumps to explore sound transmission in different media. He integrated illusions like strobic circles to illustrate auditory-visual synergies, alongside electric machines generating tones to differentiate musical from non-musical sounds. These live setups emphasized resonance effects, such as sympathetic vibrations in objects, providing clear examples of wave propagation.[38] Audience engagement remained central, with Thompson using live models for interactive resonance displays and lively narratives tailored to children, including his own daughters among the attendees, to sustain interest across six lectures. The series attracted crowded houses and reinforced the Royal Institution's tradition of science outreach, akin to efforts by Faraday and Tyndall, though no published companion volume emerged due to Thompson's commitments. By blending acoustics with optics and electricity, these lectures underscored sound's scientific foundations, inspiring broader public appreciation for physics in the early 20th century.[38][39]Other Public Lectures and Demonstrations

Throughout his career, Silvanus P. Thompson delivered numerous public lectures and demonstrations to professional and academic audiences, focusing on advancements in electricity and magnetism. In 1890, he presented a series of Cantor Lectures to the Society of Arts in London titled "The Electromagnet and Electromagnetic Mechanisms," which included practical demonstrations of electromagnetic principles and their applications in devices such as relays and motors. These lectures, delivered over four sessions from January to February, emphasized the design and efficiency of electromagnets, drawing on his expertise to illustrate how theoretical physics could inform industrial engineering.[40] In 1891, Thompson served as one of the honorary Vice-Presidents of the International Electrotechnical Exhibition in Frankfurt. As a British delegate to the International Electrical Congress in Chicago in 1893, he presented a paper titled "Ocean Telephony" on methods to diminish electromagnetic wave distortion in submarine cables, enabling improved telephony over long distances. This work highlighted his role in bridging theoretical electromagnetism with practical telegraphy advancements, influencing global standards for transoceanic communication.[8][41] In addition to domestic and transatlantic forums, Thompson participated in international expositions to demonstrate electrical innovations. His talks and displays there aimed to foster collaboration between academic researchers and industry practitioners, promoting accessible explanations of complex topics like polyphase currents and alternating-current motors—subjects he had explored in earlier lectures, such as his 1882 address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science on the advantages of alternating over direct current. Through these efforts, Thompson consistently sought to demystify electrical science for engineers and technicians, facilitating the transfer of knowledge from laboratories to industrial applications.Honors and Recognition

Awards and Fellowships

Silvanus P. Thompson was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) on 4 June 1891, in recognition of his significant contributions to electrical engineering and physics, particularly his work on electromagnetism and related mechanisms.[14][38] In 1894, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, honoring his advancements in electrical science.[38] He also received the honorary degree of Doctor of Medicine and Surgery (M.D. and C.M.) from the University of Königsberg that year.[1][38] Thompson was awarded the Society of Arts Silver Medal in 1898 for his Cantor Lecture on "Telegraphy across Space," which explored wireless communication principles.[38] The following year, the Institution of Electrical Engineers elected him President, acknowledging his foundational contributions to the field, including dynamo-electric machinery and electrical measurements.[1][38] Later honors included the honorary LL.D. from the University of Birmingham in 1909, the D.Sc. from the University of Bristol in 1912, and election as an honorary member of the Institution of Electrical Engineers in 1914, all recognizing his broad impact on physics education and research.[42][38][2] In 1913, he was elected a foreign member of the Accademia delle Scienze dell'Istituto di Bologna, further affirming his international standing in scientific circles.[38]Leadership in Scientific Societies

Silvanus P. Thompson played a pivotal role in shaping early scientific organizations dedicated to physics and radiology, leveraging his expertise to guide their development and policies. As the inaugural president of the Röntgen Society from 1897 to 1898, he led the newly formed group—later renamed the British Institute of Radiology—in its mission to explore the scientific, medical, and photographic applications of X-rays. Under his leadership, the society emphasized interdisciplinary collaboration among physicists, physicians, and technicians, establishing a foundation for standardized practices in radiology. Thompson's tenure helped position the organization as a bridge between theoretical physics and practical medical use, fostering discussions on the safe handling of X-ray equipment to prevent injuries to practitioners, which contributed to the society's early advocacy for protection standards.[4][19][21] Thompson extended his influence to broader physical sciences as president of the Physical Society of London from 1901 to 1902, where he promoted advancements in experimental physics and instrumentation. In this capacity, he advocated for policies enhancing technical education within the society, encouraging curricula that integrated practical training with theoretical knowledge to better prepare scientists for emerging technologies. His administrative experience from academic roles informed these efforts, ensuring the society addressed ethical considerations in experimentation, such as the responsible use of new apparatus in research.[43][22] He served as President of the Institution of Electrical Engineers from 1899 to 1900, where his leadership advanced the standardization of practices and education in electrical engineering. During his term, he delivered a presidential address emphasizing the economic and practical benefits of technical training, influencing the institution's approach to professional development and innovation in the field.[1]Personal Life and Legacy

Family and Personal Interests

Silvanus P. Thompson married Jane Henrietta Nottage on March 30, 1881, at the Glasgow Friends' Meeting House, following their meeting at a British Association gathering in Dublin the previous year.[44] The couple settled initially in Clifton before relocating to London in 1885, where they resided for many years at "Morland" in West Hampstead, a home that became a center for their Quaker and scientific social circles.[44] They had four daughters—Sylvia, Helen, Dorothea, and Irene—who shared in family traditions such as sketching holidays, musical evenings, and attendance at Royal Institution events; Sylvia and Irene later married, with Sylvia wedding William Hanbury Aggs in 1906 and Irene marrying T. Edmund Harvey in 1911.[44] Thompson's family life emphasized quiet domestic joys, including reading novels aloud during vacations and collaborative artistic pursuits, reflecting the continuity of his Quaker upbringing in a close-knit household.[44] Raised in a devout Quaker family, Thompson maintained a lifelong commitment to the faith, becoming a recorded Minister in 1903 and actively participating in Quaker societies such as the Friends' Portfolio Society.[44] His beliefs profoundly shaped his worldview, promoting the Inner Light and pacifism as core principles; he opposed the Boer War in 1900, decrying its inhumanities in a speech at the Westminster Friends' meeting, and consistently rejected militarism, such as declining a guard of honor during a 1899 visit to Bristol due to his conscientious objections.[44] Thompson's pacifist stance aligned with his lifelong advocacy for peace through Quaker channels.[44] Thompson's personal interests extended beyond science into artistic and intellectual realms, revealing a multifaceted character. He was an accomplished watercolor painter and sketcher from youth, having studied under Edwin Moore and exhibiting works at the Royal Water Colour Society and Alpine Club; his subjects often included Alpine scenery, optical illusions like Strobic Circles, and portraits, such as one of Michael Faraday for his biography.[44] A voracious reader and writer, he contributed poetry and essays to school magazines, admired authors like Charles Dickens, John Ruskin, Robert Browning, and Dante—whom he read in the original Italian—and penned influential biographies that blended literature with scientific history.[44] Additionally, he amassed an extensive collection of scientific instruments and historical apparatus, including vacuum tubes and magnetism devices acquired from figures like James Wimshurst, alongside a library of over 900 pre-1825 books on science and art, now preserved as the Silvanus P. Thompson Memorial Library.[44] In his later years, Thompson faced recurring health challenges, including a delicate throat from childhood scarlet fever, bouts of laryngitis, and strains from overwork, such as during revisions of his 1914 book with daughter Helen's assistance.[44] He endured typhoid fever in 1869 and influenza in 1903, yet continued active pursuits like Alpine trips in 1913 with Dorothea, who herself suffered from asthma.[44] Thompson died on June 12, 1916, at age 64 in London from a cerebral hemorrhage, following periods of fatigue exacerbated by wartime stresses and professional demands.[44]Influence on Science and Education

Silvanus P. Thompson's Calculus Made Easy, first published in 1910, played a pivotal role in democratizing mathematics education by presenting complex concepts in an accessible, intuitive manner that avoided overly abstract formalism, thereby making calculus approachable for non-specialists and students alike.[45] This approach emphasized practical understanding over rigorous proofs, influencing generations of learners and educators to prioritize clarity in teaching.[31] The book's enduring popularity is evident in its continued reprints and digital adaptations into the 2020s, including a 2020 new edition with modernized language and additional practice problems, as well as free digital versions available through Project Gutenberg, ensuring its relevance in contemporary self-study and online learning environments.[46] In the field of radiology, Thompson's early leadership as the first president of the Röntgen Society (later the British Institute of Radiology) in 1897 helped establish foundational discussions on the ethical use of X-rays, including initial recognitions of potential hazards that informed subsequent safety measures.[4] His public demonstrations and lectures on X-rays shortly after their 1895 discovery highlighted both their scientific promise and the need for caution, contributing to the society's issuance of early protection recommendations that evolved into modern protocols for minimizing radiation exposure in medical practice.[47] These efforts underscored ethical responsibilities in emerging technologies, influencing today's standardized safety guidelines enforced by organizations like the International Commission on Radiological Protection.[48] Thompson's tenure as principal and professor of physics and electrical engineering at the City and Guilds Technical College in Finsbury from 1885 to 1916 exemplified his advocacy for hands-on, practical STEM vocational training, where students engaged directly with electrical machinery and experiments rather than theoretical lectures alone.[2] This model emphasized applied skills for industrial applications and served as a blueprint for technical colleges worldwide that integrate workshop-based learning with academic instruction.[5] His approach continues to resonate in modern STEM programs, promoting experiential education that bridges theory and practice in vocational settings.[22] In 21st-century contexts, Thompson receives recognition for his foundational experiments in magnetic stimulation, such as his 1910 demonstration of induced phosphenes using a large electromagnetic coil, which prefigured modern transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) techniques used in neuroscience and psychiatry.[49] His work on electrical engineering standards, including authoritative texts like Dynamo-Electric Machinery, remains cited in historical overviews of the field, though no major updates have emerged post-2020.[2]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1927_supplement/Thompson,_Silvanus_Phillips