Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

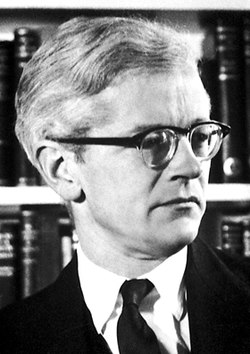

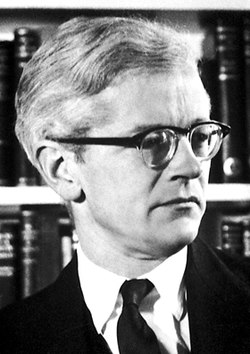

John Kendrew

View on Wikipedia

Sir John Cowdery Kendrew, CBE FRS[3] (24 March 1917 – 23 August 1997) was an English biochemist, crystallographer, and science administrator. Kendrew shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Max Perutz, for their work at the Cavendish Laboratory to investigate the structure of haem-containing proteins.

Key Information

Education and early life

[edit]Kendrew was born in Oxford, son of Wilfrid George Kendrew, reader in climatology in the University of Oxford, and Evelyn May Graham Sandburg, art historian. After preparatory school at the Dragon School in Oxford, he was educated at Clifton College[4] in Bristol, 1930–1936. He attended Trinity College, Cambridge in 1936, as a Major Scholar, graduating in chemistry in 1939. He spent the early months of World War II doing research on reaction kinetics, and then became a member of the Air Ministry Research Establishment, working on radar. In 1940 he became engaged in operational research at the Royal Air Force headquarters; commissioned a squadron leader on 17 September 1941,[5] he was appointed an honorary wing commander on 8 June 1944,[6] and relinquished his commission on 5 June 1945.[7] He was awarded his PhD after the war in 1949.[8]

Research and career

[edit]During the war years, he became increasingly interested in biochemical problems, and decided to work on the structure of proteins.

Crystallography

[edit]In 1945 he approached Max Perutz in the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge. Joseph Barcroft, a respiratory physiologist, suggested he might make a comparative protein crystallographic study of adult and foetal sheep haemoglobin, and he started that work.

In 1947 he became a Fellow of Peterhouse; and the Medical Research Council (MRC) agreed to create a research unit for the study of the molecular structure of biological systems, under the direction of Sir Lawrence Bragg.[9] In 1954 he became a Reader at the Davy-Faraday Laboratory of the Royal Institution in London.

Crystal structure of myoglobin

[edit]

Kendrew shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for chemistry with Max Perutz for determining the first atomic structures of proteins using X-ray crystallography. Their work was done at what is now the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge. Kendrew determined the structure of the protein myoglobin, which stores oxygen in muscle cells.[10]

In 1947 the MRC agreed to make a research unit for the Study of the Molecular Structure of Biological Systems. The original studies were on the structure of sheep haemoglobin, but when this work had progressed as far as was possible using the resources then available, Kendrew embarked on the study of myoglobin, a molecule only a quarter the size of the haemoglobin molecule. His initial source of raw material was horse heart, but the crystals thus obtained were too small for X-ray analysis. Kendrew realized that the oxygen-conserving tissue of diving mammals could offer a better prospect, and a chance encounter led to his acquiring a large chunk of whale meat from Peru. Whale myoglobin did give large crystals with clean X-ray diffraction patterns.[10] However, the problem still remained insurmountable, until in 1953 Max Perutz discovered that the phase problem in analysis of the diffraction patterns could be solved by multiple isomorphous replacement — comparison of patterns from several crystals; one from the native protein, and others that had been soaked in solutions of heavy metals and had metal ions introduced in different well-defined positions. An electron density map at 6 angstrom (0.6 nanometre) resolution was obtained by 1957, and by 1959 an atomic model could be built at 2 angstrom (0.2 nm) resolution.[11]

Later career

[edit]In 1963, Kendrew became one of the founders of the European Molecular Biology Organization; he also founded the Journal of Molecular Biology and was for many years its editor-in-chief. He became Fellow of the American Society of Biological Chemists in 1967 and honorary member of the International Academy of Science, Munich. In 1974, he succeeded in persuading governments to establish the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg and became its first director. He was knighted in 1974.[3] From 1974 to 1979, he was a Trustee of the British Museum, and from 1974 to 1988 he was successively Secretary General, Vice-President, and President of the International Council of Scientific Unions.

After his retirement from EMBL, Kendrew became President of St John's College at the University of Oxford, a post he held from 1981 to 1987. In his will, he designated his bequest to St John's College for studentships in science and in music, for students from developing countries. The Kendrew Quadrangle at St John's College in Oxford, officially opened on 16 October 2010, is named after him.[12]

Kendrew was married to the former Elizabeth Jarvie (née Gorvin) from 1948 to 1956. Their marriage ended in divorce. Kendrew was subsequently partners with the artist Ruth Harris.[3] He had no surviving children.[13]

A biography of Kendrew, entitled A Place in History: The Biography of John C. Kendrew, by Paul M. Wassarman was published by Oxford University Press in 2020.

Selected publications

[edit]- Kendrew, JC (April 1949). "Foetal haemoglobin". Endeavour. 8 (30): 80–5. ISSN 0160-9327. PMID 18144277.

- Kendrew, JC; Parrish, RG; Marrack, JR; Orlans, ES (November 1954). "The species specificity of myoglobin". Nature. 174 (4438): 946–9. Bibcode:1954Natur.174..946K. doi:10.1038/174946a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13214049. S2CID 4281674.

- Kendrew, JC; Parris, RG (January 1955). "Imidazole complexes of myoglobin and the position of the haem group". Nature. 175 (4448): 206–7. Bibcode:1955Natur.175..206K. doi:10.1038/175206b0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13235845. S2CID 37160617.

- Ingram, DJ; Kendrew, JC (October 1956). "Orientation of the haem group in myoglobin and its relation to the polypeptide chain direction". Nature. 178 (4539): 905–6. Bibcode:1956Natur.178..905I. doi:10.1038/178905a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13369569. S2CID 26921410.

- Kendrew, JC; Bodo, G; Dintzis, HM; Parrish, RG; Wyckoff, H; Phillips, DC (March 1958). "A three-dimensional model of the myoglobin molecule obtained by x-ray analysis". Nature. 181 (4610): 662–6. Bibcode:1958Natur.181..662K. doi:10.1038/181662a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13517261. S2CID 4162786.

- Kendrew, JC (July 1959). "Structure and function in myoglobin and other proteins". Federation Proceedings. 18 (2, Part 1): 740–51. ISSN 0014-9446. PMID 13672267.

- Kendrew, JC; Watson, HC; Strandberg, BE; Dickerson, RE; Phillips, DC; Shore, VC (May 1961). "The amino-acid sequence x-ray methods, and its correlation with chemical data". Nature. 190 (4777): 666–70. Bibcode:1961Natur.190..666K. doi:10.1038/190666a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13752474. S2CID 39469512.

- Watson, HC; Kendrew, JC (May 1961). "The amino-acid sequence of sperm whale myoglobin. Comparison between the amino-acid sequences of sperm whale myoglobin and of human hæmoglobin". Nature. 190 (4777): 670–2. Bibcode:1961Natur.190..670W. doi:10.1038/190670a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 13783432. S2CID 4170869.

- Kendrew, JC (December 1961). "The three-dimensional structure of a protein molecule". Scientific American. 205 (6): 96–110. Bibcode:1961SciAm.205f..96K. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1261-96. ISSN 0036-8733. PMID 14455128.

- Kendrew, JC (October 1962). "The structure of globular proteins". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 4 (2–4): 249–52. doi:10.1016/0010-406X(62)90009-9. ISSN 0010-406X. PMID 14031911.

- Kendrew, John C. (1966). The thread of life: an introduction to molecular biology. London: Bell & Hyman. ISBN 978-0-7135-0618-1.

References

[edit]- ^ Huxley, Hugh Esmor (1953). Investigations of biological structures by X-ray methods : the structure of muscle. lib.cam.ac.uk (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge. OCLC 885437514. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.604904. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ a b c "John Kendrew academic genealogy". academictree.org.

- ^ a b c Holmes, K. C. (2001). "Sir John Cowdery Kendrew. 24 March 1917 - 23 August 1997: Elected F.R.S. 1960". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 47: 311–332. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2001.0018. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0028-EC77-7. PMID 15124647.

- ^ "Clifton College Register" Muirhead, J.A.O. p462: Bristol; J.W Arrowsmith for Old Cliftonian Society; April, 1948

- ^ "No. 35301". The London Gazette. 7 October 1941. p. 5793.

- ^ "No. 36633". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 July 1944. p. 3562.

- ^ "No. 37168". The London Gazette (Supplement). 6 July 1945. p. 3552.

- ^ Kendrew, John Cowdery (1949). X-ray studies of certain crystalline proteins : the crystal structure of foetal and adult sheep haemoglobins and of horse myoglobin. lib.cam.ac.uk (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.648050. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ "John C. Kendrew Biographical".

- ^ a b Stoddart, Charlotte (1 March 2022). "Structural biology: How proteins got their close-up". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-022822-1. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ Kendrew, JC; Dickerson, RE; Strandberg, BE; et al. (February 1960). "Structure of myoglobin: A three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 2 A. resolution". Nature. 185 (4711): 422–7. Bibcode:1960Natur.185..422K. doi:10.1038/185422a0. PMID 18990802. S2CID 4167651.

- ^ "The 21st Century: Kendrew Quadrangle". St John's College, Oxford. 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ Wolfgang Saxon (30 August 1997). "John C. Kendrew Dies at 80; Biochemist Won Nobel in '62". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- John Finch; 'A Nobel Fellow on Every Floor', Medical Research Council 2008, 381 pp, ISBN 978-1-84046-940-0; this book is all about the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge.

- Oxford University Press, page on Paul M. Wassarman, A Place in History, ISBN 9780199732043, 2020

External links

[edit]- John C. Kendrew on Nobelprize.org

- Portraits of John Kendrew at the National Portrait Gallery, London

John Kendrew

View on GrokipediaEarly life and education

Family background and childhood

John Cowdery Kendrew was born on 24 March 1917 in Oxford, England, the son of Wilfrid George Kendrew, a reader in climatology and geography at the University of Oxford, and Evelyn May Graham (Sandberg) Kendrew, an art historian who specialized in Italian primitives and published under the name Evelyn Sandberg Vavals after living in Florence.[2][5] The family's academic pursuits created an intellectually stimulating environment that nurtured Kendrew's early interests in both scientific inquiry and the humanities, influenced by his father's meteorological research and his mother's engagement with Renaissance art.[2][6] Kendrew began his formal education at the Dragon School in Oxford in 1923, at the age of six, attending until 1930, where he was exposed to a broad curriculum that laid the foundation for his academic excellence.[2][7] In 1930, at age 13, he transferred to Clifton College in Bristol, a boarding school known for its emphasis on sciences, where he continued to perform strongly as an excellent student overall.[2][7] It was at Clifton College, from 1930 to 1936, that Kendrew's passion for science, particularly chemistry, began to take shape, sparked by inspirational teachers in chemistry, physics, and mathematics who encouraged his analytical mindset.[6][8] Beyond academics, he pursued wider cultural interests, including music and the history of Italian art, which aligned with his family's artistic heritage and reflected a balanced formative period blending scientific rigor with humanistic pursuits.[5][2]Academic training

John Cowdery Kendrew enrolled at Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1936 as a Major Scholar, pursuing the Natural Sciences Tripos with a primary focus on chemistry. His undergraduate studies encompassed foundational subjects in physics, chemistry, biochemistry, and mathematics during Part I of the Tripos, before specializing in chemistry for Part II. He graduated with First Class Honours in chemistry in June 1939, earning a Bachelor of Arts degree.[2][6] Kendrew's academic progress was interrupted by the outbreak of World War II in 1939. He initially contributed to wartime efforts through research on reaction kinetics in the Department of Physical Chemistry at Cambridge under Dr. E.A. Moelwyn-Hughes, but soon transitioned to applied work in radar development at the Air Ministry Research Station in Bawdsey. From 1940 to 1945, he served as a Wing Commander in the Royal Air Force, conducting operational research for Coastal Command in the Middle East and South East Asia, with a focus on radar applications. This period emphasized practical scientific continuity amid the conflict, though it delayed his advanced studies.[2][9] Following the war, Kendrew returned to Cambridge in 1946, spending a year in the United States before joining the Medical Research Council Unit for the Study of the Molecular Structure of Biological Systems at the Cavendish Laboratory in 1947. Under the supervision of Max Perutz, he pursued doctoral research in biophysics, culminating in a PhD awarded in 1949. His thesis examined the X-ray diffraction patterns of fetal and adult sheep hemoglobin, laying groundwork for protein crystallography techniques.[2][6] Throughout his training, Kendrew gained exposure to quantum mechanics and physical chemistry via the Cambridge curriculum, which integrated theoretical principles with experimental methods. He was particularly influenced by early theories of protein structure, inspired by lecturers such as J.D. Bernal, whose work on X-ray analysis of biological molecules highlighted the potential for determining protein architectures. These elements shaped his shift toward biophysics and structural studies.[2][6]Research career

Early scientific work

Following the end of World War II, John Kendrew returned to the University of Cambridge in 1946, where he joined Max Perutz at the Cavendish Laboratory under the direction of Sir William Lawrence Bragg, becoming one of the first two members of the newly established Medical Research Council Unit for the Study of the Molecular Structure of Biological Systems.[2] This marked a pivotal shift in Kendrew's research from general physical chemistry to the application of X-ray crystallography on biological molecules, particularly proteins, inspired by earlier influences from J.D. Bernal and Linus Pauling during the war.[2][10] Kendrew's initial experiments focused on hemoglobin, an oxygen-binding protein, where he collaborated with Perutz to develop methods for crystallizing the protein in forms suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis.[10] These efforts involved comparative studies of fetal and adult sheep hemoglobins, addressing challenges in obtaining high-quality, large crystals that could yield detailed diffraction patterns to probe molecular arrangement.[10] Drawing on his wartime expertise in radar signal processing and operational research for the Royal Air Force—where he rose to the rank of Wing Commander—Kendrew applied advanced data-handling techniques to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of analyzing complex X-ray diffraction data from protein crystals.[2][10] By the late 1940s, Kendrew had established foundational techniques for X-ray studies of oxygen-binding proteins through his doctoral research, culminating in his 1949 PhD thesis, X-ray Studies of Certain Crystalline Proteins: The Crystal Structure of Foetal and Adult Sheep Haemoglobins and of Horse Myoglobin.[10] This work included early publications on the diffraction patterns from hemoglobin crystals, laying the groundwork for higher-resolution structural investigations of proteins while highlighting differences in crystal forms between oxygenated and deoxygenated states.[10] These contributions helped pioneer the transition from low-resolution fiber diffraction methods—previously used by Perutz—to more precise three-dimensional crystal analyses in protein crystallography.[10]Myoglobin structure determination

In the early 1950s, John Kendrew initiated a project at the Medical Research Council Unit for the Study of the Molecular Structure of Biological Systems in Cambridge to determine the three-dimensional structure of myoglobin, an oxygen-storage protein found in muscle tissues.[10] Myoglobin was selected as a model system because it is smaller—about one-quarter the size of hemoglobin—and forms more stable, well-ordered crystals, facilitating X-ray analysis; after testing samples from various animals, sperm whale myoglobin proved ideal due to its "beautiful crystals."[10][11] Kendrew employed the method of isomorphous replacement, introducing heavy atoms such as mercury derivatives at multiple sites (up to five) within the protein to determine the phases of X-ray diffraction data, enabling the calculation of electron density maps.[10][11] This technique, adapted from earlier work on hemoglobin, allowed progressive refinement: an initial low-resolution map at 6 Å was obtained in 1957 using about 400 reflections, followed by a 2 Å resolution structure in 1959 incorporating around 10,000 reflections, and further improvement to 1.4 Å in 1960 with approximately 25,000 reflections.[11] The analysis relied on computational Fourier synthesis to process the vast diffraction data, marking one of the earliest applications of digital computers in structural biology.[10] The resulting structure revealed myoglobin as the first protein resolved at atomic resolution, consisting of a single polypeptide chain of about 153 amino acids folded into eight alpha-helices that comprise roughly 75% of the molecule, enclosing a heme prosthetic group.[12][11] Key features included the heme group's positioning in a hydrophobic pocket, with its iron atom slightly displaced from the porphyrin plane and coordinated by proximal and distal histidine residues that facilitate oxygen binding without carbon monoxide toxicity.[12] Contrary to earlier hypotheses that proteins might incorporate beta-sheets as major secondary structures, myoglobin contained none, highlighting alpha-helices as a dominant folding motif in globular proteins.[10][11] Overcoming the project's challenges required a sustained, multi-year effort spanning more than a decade, involving manual collection of diffraction patterns from rotating crystals and laborious phase assignments amid incomplete heavy-atom substitutions.[10] Kendrew's team addressed these hurdles through collaboration with the University of Cambridge's Mathematical Laboratory, utilizing the EDSAC I and later EDSAC II computers to perform the intensive Fourier summations that manual calculation could not handle efficiently.[11] This computational integration was pivotal, as the 2 Å map alone demanded processing equivalent to millions of arithmetic operations.[10] The landmark 2 Å structure was published in Nature in February 1960 by Kendrew and colleagues, providing the first detailed atomic model of a protein and laying foundational insights into how amino acid sequences dictate three-dimensional folding to enable biological function.[12] This achievement not only elucidated myoglobin's oxygen-binding mechanism but also revolutionized the field by demonstrating that protein structures could be empirically derived, influencing subsequent studies on folding principles and evolutionary conservation of motifs.[10][11]Broader contributions to molecular biology

Beyond his landmark determination of myoglobin's structure, which served as an early model for globular proteins, Kendrew extended his influence through collaborative efforts that illuminated the evolutionary conservation of protein architectures. Working closely with Max Perutz at the MRC Unit for the Study of the Molecular Structure of Biological Systems in Cambridge, Kendrew compared the helical folding patterns in myoglobin and hemoglobin, revealing the shared "globin fold" that underlies oxygen-binding functions across species. This comparative analysis, detailed in their 1960 publications, provided foundational insights into how protein structures evolve while maintaining functional motifs, influencing subsequent studies on protein families and divergence.[6] Kendrew's commitment to fostering molecular biology as an interdisciplinary field bridged physics, chemistry, and biology, drawing from his wartime experiences in operational research to advocate for biophysics as the "physics of life." He championed the integration of physical techniques like X-ray crystallography with biological inquiries, supporting emerging methods such as electron microscopy for visualizing protein complexes and amino acid sequence analysis for correlating primary structures with three-dimensional folds. These efforts, rooted in the 1950s and 1960s, helped legitimize molecular biology against resistance from traditional disciplines, promoting its inclusion in university curricula and research funding priorities.[13][14] A pivotal institutional contribution was Kendrew's co-founding of the Journal of Molecular Biology in 1959, alongside Sydney Brenner and others at the MRC Unit, where he served as editor-in-chief until 1987 to prioritize publications in structural biology and related fields. This outlet rapidly became a cornerstone for disseminating interdisciplinary work, enabling the field to gain mainstream recognition during its formative years. Complementing this, Kendrew cultivated a culture of open data-sharing and collaboration at the Cambridge MRC Unit—later the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology—where informal exchanges and unlocked offices symbolized the free flow of ideas, fueling breakthroughs in the "golden age" of molecular biology from the late 1950s onward.[6][10][15]Administrative roles

Leadership at MRC Laboratory

In 1962, the Medical Research Council (MRC) established the Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) in Cambridge as an independent entity, evolving from the earlier MRC Unit for the Molecular Structure of Biological Systems founded in 1947 under Max Perutz, with John Kendrew as a core member since 1946.[16][2] Kendrew was appointed Deputy Director and Deputy Chairman of the LMB upon its opening, roles in which he served until 1975, while also heading the Division of Structural Studies.[17][2] In these capacities, he collaborated closely with Perutz, who served as Chairman, to transform the laboratory into a premier institution for structural and molecular biology research.[16] Kendrew's leadership emphasized recruiting and nurturing exceptional talent, building on the existing presence of pioneers like Francis Crick and Fred Sanger to create an interdisciplinary team that included Aaron Klug, who joined in 1962 to lead structural studies on viruses and nucleic acids.[16][18] This approach fostered a collaborative culture where scientists from diverse fields—such as X-ray crystallography, genetics, and protein chemistry—shared ideas freely, often through informal discussions and shared facilities, which became a hallmark of the LMB and contributed to groundbreaking discoveries.[18] Under his and Perutz's guidance, the laboratory's environment directly supported multiple Nobel Prizes, including the 1962 awards in Chemistry to Kendrew and Perutz for protein structure elucidation and in Physiology or Medicine to Crick and James Watson for DNA's double helix.[19] During Kendrew's tenure, the LMB expanded its infrastructure to accommodate advanced techniques, with the 1962 opening of a dedicated building on Hills Road equipped for large-scale X-ray crystallography experiments essential to structural biology.[16] He played a key role in securing MRC funding for emerging technologies, including early nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy capabilities in the early 1970s and automated protein sequencing methods developed by Sanger's group, as well as computational resources for modeling complex molecular structures.[16][18] These investments positioned the LMB as a global hub for molecular biology by 1975, where innovations like the first complete amino acid sequence of a protein (insulin, by Sanger in the 1950s) and foundational work on antibody structures laid the groundwork for future breakthroughs.[16]Directorship at EMBL

Following the establishment of the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in 1974, John Kendrew became its first Director General in 1975, headquartered in Heidelberg, Germany, with the vision of creating a supranational research institution to foster collaborative molecular biology efforts across Europe and rival the scale of leading U.S. laboratories.[20][21][4] This initiative stemmed from earlier discussions among scientists, including Kendrew, James Watson, and others, dating back to 1962, aimed at pooling European resources to advance the field amid growing American dominance.[21] Operations began that year in Heidelberg and Hamburg, marking EMBL's birth as an intergovernmental organization supported by ten founding member states: Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.[22][23] Kendrew played a central role in overcoming significant political challenges during EMBL's formation, including protracted negotiations for funding and site selection amid skepticism from some governments and scientific bodies.[21] The EMBL Agreement was signed on May 10, 1973, at CERN by representatives of the ten states and ratified the following year on July 4, 1974, enabling the laboratory's legal establishment despite initial resistance, such as in the UK where support ultimately came from key figures like Shirley Williams and Margaret Thatcher.[21] Under his leadership, Kendrew facilitated the creation of outstations in Grenoble, France, and Hamburg, Germany, to leverage advanced facilities like the Institut Laue-Langevin (ILL) for neutron scattering and the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY) for X-ray crystallography, thereby establishing specialized hubs for structural biology research.[7][23] During his tenure, Kendrew emphasized the promotion of structural biology programs, integrating synchrotron radiation facilities to enhance protein crystallography and other techniques critical to molecular biology.[7] He also prioritized training young European scientists, recruiting talented researchers and fostering an environment that supported innovative, interdisciplinary work to build Europe's expertise in the life sciences.[20] Drawing briefly on his prior experience managing international teams at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Kendrew shaped EMBL into a model of pan-European collaboration.[4] Kendrew retired as Director General in 1982, leaving behind a thriving institution that embodied his vision for international scientific cooperation, as enshrined in EMBL's constitution and its ongoing role as a benchmark for supranational research organizations.[4][24] His efforts ensured EMBL's growth into a world-leading center, with outstations expanding to support diverse programs in structural and computational biology.[20]Awards and legacy

Key honors and Nobel Prize

John Cowdery Kendrew shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Max Ferdinand Perutz for their pioneering studies of the structures of globular proteins, with Kendrew specifically recognized for determining the three-dimensional atomic model of the oxygen-storage protein myoglobin.[25] The prize was announced on October 25, 1962, by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, highlighting how Kendrew's work at the Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge marked the first successful elucidation of a protein's atomic structure using X-ray crystallography. The award ceremony took place on December 10, 1962, in Stockholm, where King Gustaf VI Adolf presented the Nobel medals and diplomas.[26] In his Nobel lecture delivered the following day, titled "Myoglobin and the Structure of Proteins," Kendrew emphasized the broader implications of protein structural determination for understanding biological function, underscoring its foundational role in molecular biology.[14] Kendrew received several other distinguished honors in recognition of his contributions to structural biology. In 1963, he was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the Birthday Honours for his services to research on the molecular structure of proteins. He was knighted as a Knight Bachelor in the 1974 Birthday Honours, becoming Sir John Kendrew.[6] In 1965, the Royal Society awarded him its Royal Medal for his distinguished contributions to the complete structural analysis of the protein molecule myoglobin, particularly the elegant use of the method of isomorphous replacement.[27] Kendrew was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1960, prior to his Nobel recognition, in acknowledgment of his early advancements in protein crystallography.[28] In 1972, he was elected a foreign associate of the United States National Academy of Sciences, reflecting his international stature in the scientific community.[29]Enduring influence

John Cowdery Kendrew died on August 23, 1997, in Cambridge, England, at the age of 80.[2] His passing was commemorated in obituaries published in leading scientific journals, including Nature, which emphasized his pivotal role in establishing the foundations of molecular biology through pioneering crystallographic techniques.[30] Similarly, Structure highlighted his collaborative spirit and enduring impact on protein science.[31] Kendrew's determination of the three-dimensional structure of myoglobin in 1960 marked a breakthrough in structural biology, serving as a foundational model for understanding protein folding, function, and interactions at the atomic level.[10] This achievement provided critical insights that underpin contemporary applications in drug design—enabling the rational targeting of protein structures for therapeutic interventions—and protein engineering, where modified proteins are developed for industrial and medical uses.[32] By demonstrating the feasibility of solving complex biomolecular structures, Kendrew's work catalyzed the growth of structural biology as a discipline essential to interpreting biological mechanisms.[33] The institutions Kendrew helped shape, such as the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), remain paradigms of interdisciplinary, collaborative research that prioritize innovation and knowledge sharing.[4] The LMB, where Kendrew served as deputy chairman and played a key role in its early development, has produced 16 scientists who shared 12 Nobel Prizes, underscoring its profound influence on global scientific progress.[34] EMBL, which Kendrew co-founded and led as its first Director General from 1975 to 1982, has similarly fostered excellence, with alumni like Jacques Dubochet earning Nobel recognition for cryo-electron microscopy advancements originating from EMBL research.[35] These laboratories' models of international cooperation continue to drive breakthroughs in molecular sciences. In his personal life, Kendrew married Elizabeth Jarvie in 1948; the couple had no children and divorced in 1956.[36] From 1981 to 1987, he served as President of St John's College, Oxford, where he actively promoted science education and the integration of research into academic curricula to inspire future generations of scientists.[37] Posthumously, EMBL honors his legacy through the John Kendrew Award, which recognizes outstanding contributions to science and science communication by alumni.[38] Kendrew's foundational advancements in structural biology have extended their reach into the genomics and biotechnology sectors, informing protein-based therapies and genomic structure analyses that power modern industrial applications.[39]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:John_Kendrew