Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

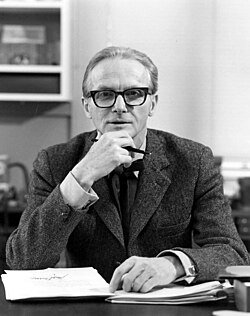

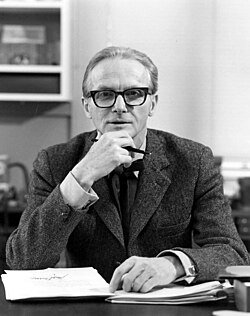

William Lipscomb

View on WikipediaWilliam Nunn Lipscomb Jr. (December 9, 1919 – April 14, 2011)[2] was a Nobel Prize-winning American inorganic and organic chemist working in nuclear magnetic resonance, theoretical chemistry, boron chemistry, and biochemistry.

Key Information

Biography

[edit]Overview

[edit]Lipscomb was born in Cleveland, Ohio, to a physician father and housewife mother. Both his grandfather and great-grandfather had been physicians.[3] His family moved to Lexington, Kentucky in 1920,[1] and he lived there until he received his Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry at the University of Kentucky in 1941. He went on to earn his Doctor of Philosophy degree in chemistry from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in 1946.

From 1946 to 1959 he taught at the University of Minnesota. From 1959 to 1990 he was a professor of chemistry at Harvard University, where he was a professor emeritus since 1990.

Lipscomb was married to the former Mary Adele Sargent from 1944 to 1983.[4] They had three children, one of whom lived only a few hours. He married Jean Evans in 1983.[5] They had one adopted daughter.

Lipscomb resided in Cambridge, Massachusetts until his death in 2011 from pneumonia.[6]

Early years

[edit]"My early home environment ... stressed personal responsibility and self reliance. Independence was encouraged especially in the early years when my mother taught music and when my father's medical practice occupied most of his time."

In grade school Lipscomb collected animals, insects, pets, rocks, and minerals.

Interest in astronomy led him to visitor nights at the Observatory of the University of Kentucky, where Prof. H. H. Downing gave him a copy of Baker's Astronomy. Lipscomb credits gaining many intuitive physics concepts from this book and from his conversations with Downing, who became Lipscomb's lifelong friend.

The young Lipscomb participated in other projects, such as Morse-coded messages over wires and crystal radio sets, with five nearby friends who became physicists, physicians, and an engineer.

Aged 12, Lipscomb was given a small Gilbert chemistry set. He expanded it by ordering apparatus and chemicals from suppliers and by using his father's privilege as a physician to purchase chemicals at the local drugstore at a discount. Lipscomb made his own fireworks and entertained visitors with color changes, odors, and explosions. His mother questioned his home chemistry hobby only once, when he attempted to isolate a large amount of urea from urine.

Lipscomb credits perusing the large medical texts in his physician father's library and the influence of Linus Pauling years later to his undertaking biochemical studies in his later years. Had Lipscomb become a physician like his father, he would have been the fourth physician in a row along the Lipscomb male line.

The source for this subsection, except as noted, is Lipscomb's autobiographical sketch.[7]

Education

[edit]Lipscomb's high-school chemistry teacher, Frederick Jones, gave Lipscomb his college books on organic, analytical, and general chemistry, and asked only that Lipscomb take the examinations. During the class lectures, Lipscomb in the back of the classroom did research that he thought was original (but he later found was not): the preparation of hydrogen from sodium formate (or sodium oxalate) and sodium hydroxide.[8] He took care to include gas analyses and to search for probable side reactions.

Lipscomb later had a high-school physics course and took first prize in the state contest on that subject. He also became very interested in special relativity.

Lipscomb attended University of Kentucky on a music scholarship. Prof. Robert H. Baker suggested that Lipscomb research the direct preparation of derivatives of alcohols from dilute aqueous solution without first separating the alcohol and water, which led to Lipscomb's first publication.[9]

For graduate school Lipscomb chose Caltech, which offered him a teaching assistantship in Physics at $20/month. He turned down more money from Northwestern University, which offered a research assistantship at $150/month. Columbia University rejected Lipscomb's application in a letter written by Nobel prizewinner Prof. Harold Urey.

At Caltech Lipscomb intended to study theoretical quantum mechanics with Prof. W. V. Houston in the physics department, but after one semester switched to the chemistry department under the influence of Prof. Linus Pauling. World War II work divided Lipscomb's time in graduate school beyond his other thesis work, as he partly analyzed smoke particle size, but mostly worked with nitroglycerin–nitrocellulose propellants, which involved handling vials of pure nitroglycerin on many occasions. Brief audio clips by Lipscomb about his war work may be found from the External Links section at the bottom of this page, past the References.

The source for this subsection, except as noted, is Lipscomb's autobiographical sketch.[7]

Scientific studies

[edit]Lipscomb worked in three main areas, nuclear magnetic resonance and the chemical shift, boron chemistry and the nature of the chemical bond, and large biochemical molecules. These areas overlap in time and share some scientific techniques. In at least the first two of these areas Lipscomb gave himself a big challenge likely to fail, and then plotted a course of intermediate goals.

Nuclear magnetic resonance and the chemical shift

[edit]

In this area Lipscomb proposed that: "... progress in structure determination, for new polyborane species and for substituted boranes and carboranes, would be greatly accelerated if the [boron-11] nuclear magnetic resonance spectra, rather than X-ray diffraction, could be used."[10] This goal was partially achieved, although X-ray diffraction is still necessary to determine many such atomic structures. The diagram at right shows a typical nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum of a borane molecule.

Lipscomb investigated, "... the carboranes, C2B10H12, and the sites of electrophilic attack on these compounds[11] using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. This work led to [Lipscomb's publication of a comprehensive] theory of chemical shifts.[12] The calculations provided the first accurate values for the constants that describe the behavior of several types of molecules in magnetic or electric fields."[13]

Much of this work is summarized in a book by Gareth Eaton and William Lipscomb, NMR Studies of Boron Hydrides and Related Compounds,[14] one of Lipscomb's two books.

Boron chemistry and the nature of the chemical bond

[edit]In this area Lipscomb originally intended a more ambitious project: "My original intention in the late 1940s was to spend a few years understanding the boranes, and then to discover a systematic valence description of the vast numbers of electron deficient intermetallic compounds. I have made little progress toward this latter objective. Instead, the field of boron chemistry has grown enormously, and a systematic understanding of some of its complexities has now begun."[15] Examples of these intermetallic compounds are KHg13 and Cu5Zn7. Of perhaps 24,000 of such compounds the structures of only 4,000 are known (in 2005) and we cannot predict structures for the others, because we do not sufficiently understand the nature of the chemical bond. This study was not successful, in part because the calculation time required for intermetallic compounds was out of reach in the 1960s, but intermediate goals involving boron bonding were achieved, sufficient to be awarded a Nobel Prize.

The three-center two-electron bond is illustrated in diborane (diagrams at right). In an ordinary covalent bond a pair of electrons bonds two atoms together, one at either end of the bond, the diborane B-H bonds for example at the left and right in the illustrations. In three-center two-electron bond a pair of electrons bonds three atoms (a boron atom at either end and a hydrogen atom in the middle), the diborane B-H-B bonds for example at the top and bottom of the illustrations.

Lipscomb's group did not propose or discover the three-center two-electron bond, nor did they develop formulas that give the proposed mechanism. In 1943, Longuet-Higgins, while still an undergraduate at Oxford, was the first to explain the structure and bonding of the boron hydrides. The paper reporting the work, written with his tutor R. P. Bell, [16] also reviews the history of the subject beginning with the work of Dilthey. [17] Shortly after, in 1947 and 1948, experimental spectroscopic work was performed by Price[18][19] that confirmed Longuet-Higgins' structure for diborane. The structure was re-confirmed by electron diffraction measurement in 1951 by K. Hedberg and V. Schomaker, with the confirmation of the structure shown in the schemes on this page.[20] Lipscomb and his graduate students further determined the molecular structure of boranes (compounds of boron and hydrogen) using X-ray crystallography in the 1950s and developed theories to explain their bonds. Later he applied the same methods to related problems, including the structure of carboranes (compounds of carbon, boron, and hydrogen). Longuet-Higgins and Roberts[21][22] discussed the electronic structure of an icosahedron of boron atoms and of the borides MB6. The mechanism of the three-center two-electron bond was also discussed in a later paper by Longuet-Higgins,[23] and an essentially equivalent mechanism was proposed by Eberhardt, Crawford, and Lipscomb.[24] Lipscomb's group also achieved an understanding of it through electron orbital calculations using formulas by Edmiston and Ruedenberg and by Boys.[25]

The Eberhardt, Crawford, and Lipscomb paper[24] discussed above also devised the "styx rule" method to catalog certain kinds of boron-hydride bonding configurations.

Wandering atoms was a puzzle solved by Lipscomb[26] in one of his few papers with no co-authors. Compounds of boron and hydrogen tend to form closed cage structures. Sometimes the atoms at the vertices of these cages move substantial distances with respect to each other. The diamond-square-diamond mechanism (diagram at left) was suggested by Lipscomb to explain this rearrangement of vertices. Following along in the diagram at left for example in the faces shaded in blue, a pair of triangular faces has a left-right diamond shape. First, the bond common to these adjacent triangles breaks, forming a square, and then the square collapses back to an up-down diamond shape by bonding the atoms that were not bonded before. Other researchers have discovered more about these rearrangements.[27] [28]

The B10H16 structure (diagram at right) determined by Grimes, Wang, Lewin, and Lipscomb found a bond directly between two boron atoms without terminal hydrogens, a feature not previously seen in other boron hydrides.[29]

Lipscomb's group developed calculation methods, both empirical[14] and from quantum mechanical theory.[30][31] Calculations by these methods produced accurate Hartree–Fock self-consistent field (SCF) molecular orbitals and were used to study boranes and carboranes.

The ethane barrier to rotation (diagram at left) was first calculated accurately by Pitzer and Lipscomb[32] using the Hartree–Fock (SCF) method.

Lipscomb's calculations continued to a detailed examination of partial bonding through "... theoretical studies of multicentered chemical bonds including both delocalized and localized molecular orbitals."[10] This included "... proposed molecular orbital descriptions in which the bonding electrons are delocalized over the whole molecule."[33]

"Lipscomb and his coworkers developed the idea of transferability of atomic properties, by which approximate theories for complex molecules are developed from more exact calculations for simpler but chemically related molecules,..."[33]

Subsequent Nobel Prize winner Roald Hoffmann was a doctoral student [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] in Lipscomb's laboratory. Under Lipscomb's direction the Extended Hückel method of molecular orbital calculation was developed by Lawrence Lohr[15] and by Roald Hoffmann.[35][39] This method was later extended by Hoffman.[40] In Lipscomb's laboratory this method was reconciled with self-consistent field (SCF) theory by Newton[41] and by Boer.[42]

Noted boron chemist M. Frederick Hawthorne conducted early[43][44] and continuing[45][46] research with Lipscomb.

Much of this work is summarized in a book by Lipscomb, Boron Hydrides,[39] one of Lipscomb's two books.

The 1976 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Lipscomb "for his studies on the structure of boranes illuminating problems of chemical bonding".[47] In a way this continued work on the nature of the chemical bond by his doctoral advisor at the California Institute of Technology, Linus Pauling, who was awarded the 1954 Nobel Prize in Chemistry "for his research into the nature of the chemical bond and its application to the elucidation of the structure of complex substances."[48]

The source for about half of this section is Lipscomb's Nobel Lecture.[10][15]

Large biological molecule structure and function

[edit]Lipscomb's later research focused on the atomic structure of proteins, particularly how enzymes work. His group used x-ray diffraction to solve the three-dimensional structure of these proteins to atomic resolution, and then to analyze the atomic detail of how the molecules work.

The images below are of Lipscomb's structures from the Protein Data Bank[49] displayed in simplified form with atomic detail suppressed. Proteins are chains of amino acids, and the continuous ribbon shows the trace of the chain with, for example, several amino acids for each turn of a helix.

Carboxypeptidase A[50] (left) was the first protein structure from Lipscomb's group. Carboxypeptidase A is a digestive enzyme, a protein that digests other proteins. It is made in the pancreas and transported in inactive form to the intestines where it is activated. Carboxypeptidase A digests by chopping off certain amino acids one-by-one from one end of a protein. The size of this structure was ambitious. Carboxypeptidase A was a much larger molecule than anything solved previously.

Aspartate carbamoyltransferase.[51] (right) was the second protein structure from Lipscomb's group. For a copy of DNA to be made, a duplicate set of its nucleotides is required. Aspartate carbamoyltransferase performs a step in building the pyrimidine nucleotides (cytosine and thymidine). Aspartate carbamoyltransferase also ensures that just the right amount of pyrimidine nucleotides is available, as activator and inhibitor molecules attach to aspartate carbamoyltransferase to speed it up and to slow it down. Aspartate carbamoyltransferase is a complex of twelve molecules. Six large catalytic molecules in the interior do the work, and six small regulatory molecules on the outside control how fast the catalytic units work. The size of this structure was ambitious. Aspartate carbamoyltransferase was a much larger molecule than anything solved previously.

Leucine aminopeptidase,[52] (left) a little like carboxypeptidase A, chops off certain amino acids one-by-one from one end of a protein or peptide.

HaeIII methyltransferase[53] (right) binds to DNA where it methylates (adds a methy group to) it.

Human interferon beta[54] (left) is released by lymphocytes in response to pathogens to trigger the immune system.

Chorismate mutase[55] (right) catalyzes (speeds up) the production of the amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine.

Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase[56] (left) and its inhibitor MB06322 (CS-917)[57] were studied by Lipscomb's group in a collaboration, which included Metabasis Therapeutics, Inc., acquired by Ligand Pharmaceuticals[58] in 2010, exploring the possibility of finding a treatment for type 2 diabetes, as the MB06322 inhibitor slows the production of sugar by fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase.

Lipscomb's group also contributed to an understanding of concanavalin A[59] (low resolution structure), glucagon,[60] and carbonic anhydrase[61] (theoretical studies).

Subsequent Nobel Prize winner Thomas A. Steitz was a doctoral student in Lipscomb's laboratory. Under Lipscomb's direction, after the training task of determining the structure of the small molecule methyl ethylene phosphate,[62] Steitz made contributions to determining the atomic structures of carboxypeptidase A [50] [63] [64] [65] [66] [67] [68] [69] and aspartate carbamoyltransferase. [70] Steitz was awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for determining the even larger structure of the large 50S ribosomal subunit, leading to an understanding of possible medical treatments.

Subsequent Nobel Prize winner Ada Yonath, who shared the 2009 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Thomas A. Steitz and Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, spent some time in Lipscomb's lab where both she and Steitz were inspired to pursue later their own very large structures.[71] This was while she was a postdoctoral student at MIT in 1970.

Other results

[edit]

The mineral lipscombite (picture at right) was named after Professor Lipscomb by the mineralogist John Gruner who first made it artificially.

Low-temperature x-ray diffraction was pioneered in Lipscomb's laboratory[72][73][74] at about the same time as parallel work in Isadore Fankuchen's laboratory[75] at the then Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn. Lipscomb began by studying compounds of nitrogen, oxygen, fluorine, and other substances that are solid only below liquid nitrogen temperatures, but other advantages eventually made low-temperatures a normal procedure. Keeping the crystal cold during data collection produces a less-blurry 3-D electron-density map because the atoms have less thermal motion. Crystals may yield good data in the x-ray beam longer because x-ray damage may be reduced during data collection and because the solvent may evaporate more slowly, which for example may be important for large biochemical molecules whose crystals often have a high percentage of water.

Other important compounds were studied by Lipscomb and his students. Among these are hydrazine,[76] nitric oxide,[77] metal-dithiolene complexes,[78] methyl ethylene phosphate,[62] mercury amides,[79] (NO)2,[80] crystalline hydrogen fluoride,[81] Roussin's black salt,[82] (PCF3)5,[83] complexes of cyclo-octatetraene with iron tricarbonyl,[84] and leurocristine (Vincristine),[85] which is used in several cancer therapies.

Positions, awards and honors

[edit]- Guggenheim Fellow, 1954[86]

- Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1960.[87]

- Member of United States National Academy of Sciences

- Member of the Faculty Advisory Board of MIT-Harvard Research Journal

- Foreign Member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (1976)[88]

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1976)

Five books and published symposia are dedicated to Lipscomb.[7][89][90][91][92]

A complete list of Lipscomb's awards and honors is in his Curriculum Vitae.[93]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e William Lipscomb on Nobelprize.org , accessed 30 May 2020

- ^ Rifkin, Glenn (2011-04-15). "William Lipscomb, Nobel Winner in Chemistry, Dies at 91". The New York Times.

- ^ Grimes, Russell (18 May 2011). "William Nunn Lipscomb Jr (1919–2011)". Nature. 473 (7347): 286. Bibcode:2011Natur.473..286G. doi:10.1038/473286a. PMID 21593854.

- ^ LorraineGilmer02 (2007-09-27). "obit fyi – Mary Adele Sargent Lipscomb, 1923 Ca. – 2007 NC – Sargent – Family History & Genealogy Message Board – Ancestry.com". Boards.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Maugh II, Thomas H. (2011-04-16). "OBITUARY: William N. Lipscomb dies at 91; won Nobel Prize in chemistry – Los Angeles Times". Articles.latimes.com. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- ^ Kauffman, George B.; Jean-Pierre Adloff (19 July 2011). "William Nunn Lipscomb Jr. (1919–2011), Nobel Laureate and Borane Chemistry Pioneer: An Obituary–Tribute" (PDF). The Chemical Educator. 16: 195–201. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Structures and Mechanisms: From Ashes to Enzymes (Acs Symposium Series) Gareth R. Eaton (Editor), Don C. Wiley (Editor), Oleg Jardetzky (Editor), .American Chemical Society, Washington, D.C., 2002 ("Process of Discovery (1977); An Autobiographical Sketch" by William Lipscomb, 14 pp. (Lipscombite: p. xvii), and Chapter 1: "The Landscape and the Horizon. An Introduction to the Science of William N. Lipscomb", by Gareth Eaton, 16 pp.) These chapters are online at pubs.acs.org. Click PDF symbols at right.

- ^ "HighSchool – Publications – Lipscomb". Wlipscomb.tripod.com. 1937-02-25. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- ^ Lipscomb, W. N.; Baker, R. H. (1942). "The Identification of Alcohols in Aqueous Solution". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 64: 179–180. Bibcode:1942JAChS..64..179L. doi:10.1021/ja01253a505.

- ^ a b c Lipscomb, WN (1977). "The Boranes and Their Relatives". Science. 196 (4294): 1047–1055. Bibcode:1977Sci...196.1047L. doi:10.1126/science.196.4294.1047. PMID 17778522. S2CID 46658615.

- ^ Potenza, J. A.; Lipscomb, W. N.; Vickers, G. D.; Schroeder, H. (1966). "Order of Electrophilic Substitution in 1,2 Dicarbaclovododecaborane(12) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Assignment". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 88 (3): 628–629. Bibcode:1966JAChS..88..628P. doi:10.1021/ja00955a059.

- ^ Lipscomb WN, The chemical shift and other second-order magnetic and electric properties of small molecules. Advances in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Edited by J. Waugh, Vol. 2 (Academic Press, 1966), pp. 137-176

- ^ Hutchinson Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Lipscomb, William Nunn (1919-) (5 paragraphs) © RM, 2011, all rights reserved, as published under license in AccessScience, The McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology Online, © The McGraw-Hill Companies, 2000–2008. Helicon Publishing is a division of RM. To see this biography (1) Go to accessscience.com (2) Search for Lipscomb (3) at right Click on "Lipscomb, William Nunn (1919- ). (4) If no institutional access is available, then at right click on Purchase Now (price in 2011 is about $30 US including tax for 24 hours). (5) Log in (6) Repeat steps 2 and 3.to see Lipscomb's biography.

- ^ a b Eaton GR, Lipscomb, WN. 1969. NMR Studies of Boron Hydrides and Related Compounds. W. A. Benjamin, Inc.

- ^ a b c Lipscomb WN. 1977. The Boranes and Their Relatives. in Les Prix Nobel en 1976. Imprimerie Royal PA Norstedt & Soner, Stockholm. 110-131.[1][2] Quote in next to last paragraph, which is omitted in Science version of the paper.

- ^ Longuet-Higgins, H. C.; Bell, R. P. (1943). "64. The Structure of the Boron Hydrides". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed). 1943: 250–255. doi:10.1039/JR9430000250.

- ^ Dilthey, W. (1921). "Uber die Konstitution des Wassers". Z. Angew. Chem. 34 (95): 596. doi:10.1002/ange.19210349509.

- ^ Price, W.C. (1947). "The structure of diborane". J. Chem. Phys. 15 (8): 614. doi:10.1063/1.1746611.

- ^ Price, W.C. (1948). "The absorption spectrum of diborane". J. Chem. Phys. 16 (9): 894. Bibcode:1948JChPh..16..894P. doi:10.1063/1.1747028.

- ^ Hedberg, K.; Schomaker, V. (1951). "A Reinvestigation of the Structures of Diborane and Ethane by Electron Diffraction". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 73 (4): 1482–1487. Bibcode:1951JAChS..73.1482H. doi:10.1021/ja01148a022.

- ^ Longuet-Higgins, H. C.; Roberts, M. de V. (1954). "The electronic structure of the borides MB6". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 224 (1158): 336–347. Bibcode:1954RSPSA.224..336L. doi:10.1098/rspa.1954.0162. S2CID 137957004.

- ^ Longuet-Higgins, H. C.; Roberts, M. de V. (1955). "The electronic structure of an icosahedron of boron atoms". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 230 (1180): 110–119. Bibcode:1955RSPSA.230..110L. doi:10.1098/rspa.1955.0115. S2CID 98533477.

- ^ H. C. Longuet-Higgins (1953). "title unknown". J. Roy. Inst. Chem. 77: 197.

- ^ a b Eberhardt, W. H.; Crawford, B.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1954). "The Valence Structure of the Boron Hydrides". J. Chem. Phys. 22 (6): 989. Bibcode:1954JChPh..22..989E. doi:10.1063/1.1740320.

- ^ Kleier, D. A.; Hall, J. H. Jr.; Halgren, T. A.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1974). "Localized Molecular Orbitals for Polyatomic Molecules. I. A Comparison of the Edmiston-Ruedenberg and the Boys Localization Methods". J. Chem. Phys. 61 (10): 3905. Bibcode:1974JChPh..61.3905K. doi:10.1063/1.1681683.

- ^ Lipscomb, W. N. (1966). "Framework Rearrangement in Boranes and Carboranes". Science. 153 (3734): 373–378. Bibcode:1966Sci...153..373L. doi:10.1126/science.153.3734.373. PMID 17839704.

- ^ Hutton, Brian W.; MacIntosh, Fraser; Ellis, David; Herisse, Fabien; Macgregor, Stuart A.; McKay, David; Petrie-Armstrong, Victoria; Rosair, Georgina M.; Perekalin, Dmitry S.; Tricas, Hugo; Welch, Alan J. (2008). "Unprecedented steric deformation of ortho-carborane". Chemical Communications (42): 5345–5347. doi:10.1039/B810702E. PMID 18985205.

- ^ Hosmane, N.S.; Zhang, H.; Maguire, J.A.; Wang, Y.; Colacot, T.J.; Gray, T.G. (1996). "The First Carborane with a Distorted Cuboctahedral Structure". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 35 (9): 1000–1002. doi:10.1002/anie.199610001.

- ^ Grimes, R.; Wang, F. E.; Lewin, R.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1961). "A New Type of Boron Hydride, B10H16". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 47 (7): 996–999. Bibcode:1961PNAS...47..996G. doi:10.1073/pnas.47.7.996. PMC 221316. PMID 16590861.

- ^ Pitzer, R. M.; Kern, C. W.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1962). "Evaluation of Molecular Integrals by Solid Spherical Harmonic Expansions". J. Chem. Phys. 37 (2): 267. Bibcode:1962JChPh..37..267P. doi:10.1063/1.1701315.

- ^ Stevens, RM; Pitzer, RM; Lipscomb, WN. (1963). "Perturbed Hartree–Fock Calculations. I. Magnetic Susceptibility and Shielding in the LiH Molecule". J. Chem. Phys. 38 (2): 550–560. Bibcode:1963JChPh..38..550S. doi:10.1063/1.1733693.

- ^ Pitzer, RM; Lipscomb, WN (1963). "Calculation of the Barrier to Internal Rotation in Ethane". J. Chem. Phys. 39 (8): 1995–2004. Bibcode:1963JChPh..39.1995P. doi:10.1063/1.1734572.

- ^ a b Getman, Thomas D. (2014). "Carborane". AccessScience. doi:10.1036/1097-8542.109100.

- ^ Hoffmann, R; Lipscomb, WN (1962). "Theory of Polyhedral Molecules. III. Population Analyses and Reactivities for the Carboranes". J. Chem. Phys. 36 (12): 3489. Bibcode:1962JChPh..36.3489H. doi:10.1063/1.1732484.

- ^ a b Hoffmann, R; Lipscomb, WN (1962). "Theory of Polyhedral Molecules. I. Physical Factorizations of the Secular Equation". J. Chem. Phys. 36 (8): 2179. Bibcode:1962JChPh..36.2179H. doi:10.1063/1.1732849.

- ^ Hoffmann, R; Lipscomb, WN (1962). "The Boron Hydrides; LCAO-MO and Resonance Studies". J. Chem. Phys. 37 (12): 2872. Bibcode:1962JChPh..37.2872H. doi:10.1063/1.1733113.

- ^ Hoffmann, R; Lipscomb, WN (1962). "Sequential Substitution Reactions on B10H10-2 and B12H12-2". J. Chem. Phys. 37 (3): 520. Bibcode:1962JChPh..37..520H. doi:10.1063/1.1701367. S2CID 95702477.

- ^ Hoffmann, R; Lipscomb, WN (1963). "Intramolecular Isomerization and Transformations in Carboranes and Substituted Boron Hydrides". Inorg. Chem. 2: 231–232. doi:10.1021/ic50005a066.

- ^ a b Lipscomb WN. Boron Hydrides, W. A. Benjamin Inc., New York, 1963 (Calculation methods are in Chapter 3).

- ^ Hoffmann, R. (1963). "An Extended Hückel Theory. I. Hydrocarbons". J. Chem. Phys. 39 (6): 1397–1412. Bibcode:1963JChPh..39.1397H. doi:10.1063/1.1734456.

- ^ Newton, MD; Boer, FP; Lipscomb, WN (1966). "Molecular Orbital Theory for Large Molecules. Approximation of the SCF LCAO Hamiltonian Matrix". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 88 (2353–2360): 245. Bibcode:1966JAChS..88.2353N. doi:10.1021/ja00963a001.

- ^ Boer, FP; Newton, MD; Lipscomb, WN. (1966). "Molecular Orbitals for Boron Hydrides Parameterized from SCF Model Calculations". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 88 (11): 2361–2366. Bibcode:1966JAChS..88.2361B. doi:10.1021/ja00963a002.

- ^ Lipscomb, W. N.; Pitochelli, A. R.; Hawthorne, M. F. (1959). "Probable Structure of the B10H10−2 Ion". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 81 (21): 5833. Bibcode:1959JAChS..81.5833L. doi:10.1021/ja01530a073.

- ^ Pitochelli, A. R.; Lipscomb, W. N.; Hawthorne, M. F. (1962). "Isomers of B20H18−2". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 84 (15): 3026–3027. Bibcode:1962JAChS..84.3026P. doi:10.1021/ja00874a042.

- ^ Lipscomb, W. N.; Wiersma, R. J.; Hawthorne, M. F. (1972). "Structural Ambiguity of the B10H14−2 Ion". Inorg. Chem. 11 (3): 651–652. doi:10.1021/ic50109a052.

- ^ Paxson, T. E.; Hawthorne, M. F.; Brown, L. D.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1974). "Observations Regarding Cu-H-B Interactions in Cu2B10H10". Inorg. Chem. 13 (11): 2772–2774. doi:10.1021/ic50141a048.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1976". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1954". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- ^ "rcsb.org". rcsb.org. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- ^ a b Lipscomb, WN; Hartsuck, JA; Reeke, GN Jr; Quiocho, FA; Bethge, PH; Ludwig, ML; Steitz, TA; Muirhead, H; et al. (June 1968). "The structure of carboxypeptidase A. VII. The 2.0-angstrom resolution studies of the enzyme and of its complex with glycyltyrosine, and mechanistic deductions". Brookhaven Symp Biol. 21 (1): 24–90. PMID 5719196.

- ^ Honzatko, R. B.; Crawford, J. L.; Monaco, H. L.; Ladner, J. E.; Edwards, B. F. P.; Evans, D. R.; Warren, S. G.; Wiley, D. C.; et al. (1983). "Crystal and molecular structures of native and CTP-liganded aspartate carbamoyltransferase from Escherichia coli". J. Mol. Biol. 160 (2): 219–263. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(82)90175-9. PMID 6757446.

- ^ Burley, S. K.; David, P. R.; Sweet, R. M.; Taylor, A.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1992). "Structure Determination and Refinement of Bovine Lens Leucine Aminopeptidase and its Complex with Bestatin". J. Mol. Biol. 224 (1): 113–140. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(92)90580-d. PMID 1548695.

- ^ Reinisch, K. M.; Chen, L.; Verdine, G. L.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1995). "The crystal structure of the Hae III methyltransferase covalently complexed to DNA: An extrahelical cytosine and rearranged base pairing". Cell. 82 (1): 143–153. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90060-8. PMID 7606780. S2CID 14417486.

- ^ Karpusas, M.; Nolte, M.; Benton, C. B.; Meier, W.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1997). "The crystal structure of human interferon beta at 2.2-A resolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94 (22): 11813–11818. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9411813K. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.22.11813. PMC 23607. PMID 9342320.

- ^ Strater, N.; Schnappauf, G.; Braus, G.; Lipscomb, W.N. (1997). "Mechanisms of catalysis and allosteric regulation of yeast chorismate mutase from crystal structures". Structure. 5 (11): 1437–1452. doi:10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00294-3. PMID 9384560.

- ^ Ke, H.; Thorpe, C. M.; Seaton, B. A.; Lipscomb, W. N.; Marcus, F. (1989). "Structure Refinement of Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and its Fructose-2,6-bisphosphate Complex at 2.8 A Resolution". J. Mol. Biol. 212 (3): 513–539. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(90)90329-k. PMID 2157849.

- ^ Erion, M. D.; Van Poelje, P. D.; Dang, Q; Kasibhatla, S. R.; Potter, S. C.; Reddy, M. R.; Reddy, K. R.; Jiang, T; Lipscomb, W. N. (May 2005). "MB06322 (CS-917): A potent and selective inhibitor of fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase for controlling gluconeogenesis in type 2 diabetes". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 102 (22): 7970–5. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.7970E. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502983102. PMC 1138262. PMID 15911772.

- ^ "ligand.com". ligand.com. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

- ^ Quiocho, F. A.; Reeke, G. N.; Becker, J. W.; Lipscomb, W. N.; Edelman, G. M. (1971). "Structure of Concanavalin A at 4 A Resolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 68 (8): 1853–1857. Bibcode:1971PNAS...68.1853Q. doi:10.1073/pnas.68.8.1853. PMC 389307. PMID 5288772.

- ^ Haugen, W. P.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1969). "The Crystal and Molecular Structure of the Hormone Glucagon". Acta Crystallogr. A. 25 (S185).

- ^ Liang, J .-Y ., & Lipscomb, W. N., "Substrate and Inhibitor Binding to Human Carbonic Anhydrase II: a Theoretical Study", International Workshop on Carbonic Anhydrase (Spoleto, Italy VCH Verlagsgesellschaft, 1991) pp. 50-64.

- ^ a b Steitz, T. A.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1965). "Molecular Structure of Methyl Ethylene Phosphate". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 87 (11): 2488–2489. Bibcode:1965JAChS..87.2488S. doi:10.1021/ja01089a031.

- ^ Hartsuck, JA; Ludwig, ML; Muirhead, H; Steitz, TA; Lipscomb, WN. (1965). "Carbyxypeptidase A, II, The Three-dimensional Electron Density Map at 6 A Resolution". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 53 (2): 396–403. Bibcode:1965PNAS...53..396H. doi:10.1073/pnas.53.2.396. PMC 219526. PMID 16591261.

- ^ Lipscomb, W. N.; Coppola, J. C.; Hartsuck, J. A.; Ludwig, M. L.; Muirhead, H.; Searl, J.; Steitz, T. A. (1966). "The Structure of Carboxypeptidase A. III. Molecular Structure at 6 A Resolution". J. Mol. Biol. 19 (2): 423–441. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(66)80014-1.

- ^ Ludwig, M. L., Coppola, J. C., Hartsuck, J. A., Muirhead, H., Searl, J., Steitz, T. A. and Lipscomb, W. N., "Molecular Structure of Carboxypeptidase A at 6 A Resolution", Federation Proceedings 25, Part I, 346 (1966).

- ^ Ludwig, ML; Hartsuck, JA; Steitz, TA; Muirhead, H; Coppola, JC; Reeke, GN; Lipscomb, WN. (1967). "The Structure of Carboxypeptidase A, IV. Prelimitary Results at 2.8 A Resolution, and a Substrate Complex at 6 A Resolution". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 57 (3): 511–514. doi:10.1073/pnas.57.3.511. PMC 335537.

- ^ Reeke, GN; Hartsuck, JA; Ludwig, ML; Quiocho, FA; Steitz, TA; Lipscomb, WN. (1967). "The structure of carboxypeptidase A. VI. Some Results at 2.0-A Resolution, and the Complex with Glycyl-Tyrosine at 2.8-A Resolution". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 58 (6): 2220–2226. Bibcode:1967PNAS...58.2220R. doi:10.1073/pnas.58.6.2220. PMC 223823. PMID 16591584.

- ^ Lipscomb, W. N; Ludwig, M. L.; Hartsuck, J. A.; Steitz, T. A.; Muirhead, H.; Coppola, J. C.; Reeke, G. N.; Quiocho, F. A. (1967). "Molecular Structure of Carboxypeptidase A at 2.8 A Resolution and an Isomorphous Enzyme-Substrate Complex at 6 A Resolution". Federation Proceedings. 26: 385.

- ^ Coppola, J. C., Hartsuck, J. A., Ludwig, M. L., Muirhead, H., Searl, J., Steitz, T. A. and Lipscomb, W. N., "The Low Resolution Structure of Carboxypeptidase A", Acta Crystallogr. 21, A160 (1966).

- ^ Steitz, TA; Wiley, DC; Lipscomb (November 1967). "The structure of aspartate transcarbamylase, I. A molecular twofold axis in the complex with cytidine triphosphate". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 58 (5): 1859–1861. Bibcode:1967PNAS...58.1859S. doi:10.1073/pnas.58.5.1859. PMC 223875. PMID 5237487.

- ^ Yarnell, A (2009). "Lipscomb Feted in Honor of his 90th Birthday". Chemical and Engineering News. 87 (48): 35. doi:10.1021/cen-v087n048.p035a.

- ^ Abrahams, SC; Collin, RL; Lipscomb, WN; Reed, TB. (1950). "Further Techniques in Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction Studies at Low Temperatures". Rev. Sci. Instrum. 21 (4): 396–397. Bibcode:1950RScI...21..396A. doi:10.1063/1.1745593.

- ^ King, M. V.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1950). "The Low Temperature Modification of n-Propylammonium Chloride". Acta Crystallogr. 3 (3): 227–230. Bibcode:1950AcCry...3..227K. doi:10.1107/s0365110x50000562.

- ^ Milberg, M. E.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1951). "The Crystal Structure of 1,2-Dichloroethane at -50°C". Acta Crystallogr. 4 (4): 369–373. Bibcode:1951AcCry...4..369M. doi:10.1107/s0365110x51001148.

- ^ Kaufman, HS; Fankuchen, I. (1949). "A Low Temperature Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction Technique". Rev. Sci. Instrum. 20 (10): 733–734. Bibcode:1949RScI...20..733K. doi:10.1063/1.1741367. PMID 15391618.

- ^ Collin, R. L.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1951). "The Crystal Structure of Hydrazine". Acta Crystallogr. 4 (1): 10–14. Bibcode:1951AcCry...4...10C. doi:10.1107/s0365110x51000027.

- ^ Dulmage, W. J.; Meyers, E. A.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1951). "The Molecular and Crystal Structure of Nitric Oxide Dimer". J. Chem. Phys. 19 (11): 1432. Bibcode:1951JChPh..19.1432D. doi:10.1063/1.1748094.

- ^ Enemark, J. H.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1965). "Molecular Structure of the Dimer of Bis(cis-1,2-bis(trifluoromethyl)-ethylene-1,2-dithiolate)cobalt". Inorg. Chem. 4 (12): 1729–1734. doi:10.1021/ic50034a012.

- ^ Lipscomb, W. N. (1957). "Recent Studies in the Structural Inorganic Chemistry of Mercury", Mercury and Its Compounds". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 65 (5): 427–435. Bibcode:1956NYASA..65..427L. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1956.tb36648.x. S2CID 84983851.

- ^ Lipscomb, W. N. (1971). "Structure of (NO)2 in the Molecular Crystal". J. Chem. Phys. 54 (8): 3659–3660. doi:10.1063/1.1675406.

- ^ Atoji, M.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1954). "The Crystal Structure of Hydrogen Fluoride". Acta Crystallogr. 7 (2): 173–175. Bibcode:1954AcCry...7..173A. doi:10.1107/s0365110x54000497.

- ^ Johansson, G.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1958). "The Structure of Roussin's Black Salt, CsFe4S3(NO)7.H2O". Acta Crystallogr. 11 (9): 594. Bibcode:1958AcCry..11..594J. doi:10.1107/S0365110X58001596.

- ^ Spencer, C. J.; Lipscomb, W (1961). "The Molecular and Crystal Structure of (PCF3)5". Acta Crystallogr. 14 (3): 250–256. Bibcode:1961AcCry..14..250S. doi:10.1107/s0365110x61000826.

- ^ Dickens, B.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1962). "Molecular and Valence Structures of Complexes of Cyclo-Octatetraene with Iron Tricarbonyl". J. Chem. Phys. 37 (9): 2084–2093. Bibcode:1962JChPh..37.2084D. doi:10.1063/1.1733429.

- ^ Moncrief, J. W.; Lipscomb, W. N. (1965). "Structures of Leurocristine (Vincristine) and Vincaleukoblastine. X-ray Analysis of Leurocristine Methiodide". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 87 (21): 4963–4964. Bibcode:1965JAChS..87.4963M. doi:10.1021/ja00949a056. PMID 5844471.

- ^ "All Fellows: L". John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780-2010: Chapter L" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ "W.N. Lipscomb". Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ The Selected Papers of William N Lipscomb Jr.: A Legacy in Structure–Function Relationships. Jainpeng Ma (Editor), Imperial College Press. 400 pp. approx. Winter 2012. (I. C. Press) Archived 2012-04-15 at the Wayback Machine (Amazon)

- ^ Boron Science: New Technologies and Applications. Narayan Hosmane (Editor), CRC Press, 878 pp. Sept, 26, 2011. (CRC Press Archived 2012-10-15 at the Wayback Machine) (Amazon)

- ^ Proceedings of the International Symposium on Quantum Chemistry, Solid-State Theory and Molecular Dynamics, International Journal of Quantum Chemistry, Quantum Chemistry Symposium No. 25, St. Augustine, Florida, March 9–16 (1991). Ed. P.O. Lowdin, Special Eds. N.Y. Orhn, J.R. Sabin, and M.C. Zemer. Published by John Wiley and Sons. 1991.

- ^ Electron Deficient Boron and Carbon Clusters, Eds: G.A. Olah, K. Wade, and R.E. Williams. An outgrowth of the January 1989 research symposium at the Loker Hydrocarbon Research Institute on Electron Deficient Clusters. Wiley – Interscience, New York, 1989. (Dedication to "The Colonel" by F. Albert Cotton, 3 pp.)

- ^ "CV – Biog – Publications – Lipscomb". Wlipscomb.tripod.com. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

External links

[edit]- "Reflections" on Linus Pauling: Video of a talk by Lipscomb. See especially the "Linus and Me" section.

- World War 2 research in brief audio clips by Lipscomb, which include his attempt to save the life of Elizabeth Swingle. Technical description of the Swingle accident.

- Scientific Character of W. Lipscomb Curriculum Vitae, publication list, science humor, Nobel Prize scrapbook, scientific aggression, family stories, portraits, eulogy.

- William Lipscomb on Nobelprize.org

- Douglas C. Rees, "William N. Lipscomb", Biographical Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences (2019)