Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Device driver

View on Wikipedia| Operating systems |

|---|

|

| Common features |

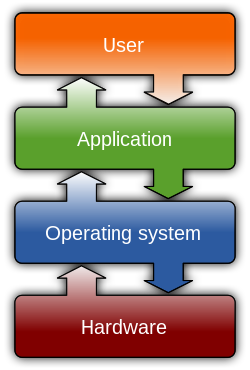

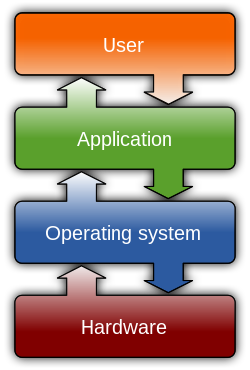

In the context of an operating system, a device driver is a computer program that operates or controls a particular type of device that is attached to a computer.[1] A driver provides a software interface to hardware devices, enabling operating systems and other computer programs to access hardware functions without needing to know precise details about the hardware.

A driver communicates with the device through the computer bus or communications subsystem to which the hardware connects. When a calling program invokes a routine in the driver, the driver issues commands to the device (drives it). Once the device sends data back to the driver, the driver may invoke routines in the original calling program.

Drivers are hardware-dependent and operating-system-specific. They usually provide the interrupt handling required for any necessary asynchronous time-dependent hardware interface.[2]

Purpose

[edit]The main purpose of device drivers is to provide hardware abstraction by acting as a translator between a hardware device and the applications or operating systems that use it.[1] Programmers can write higher-level application code independently of whatever specific hardware the end-user is using.

For example, a high-level application for interacting with a serial port may simply have two functions for send data and receive data. At a lower level, a device driver implementing these functions would communicate with the particular serial port controller installed on a user's computer. The commands needed to control a 16550 UART are much different from the commands needed to control an USB-to-serial adapter, but each hardware-specific device driver abstracts these details into the same (or similar) software interface.

Development

[edit]Writing a device driver requires an in-depth understanding of how the hardware and the software works for a given platform function. Because drivers require low-level access to hardware functions in order to operate, drivers typically operate in a highly privileged environment and can cause system operational issues if something goes wrong. In contrast, most user-level software on modern operating systems can be stopped without greatly affecting the rest of the system. Even drivers executing in user mode can crash a system if the device is erroneously programmed. These factors make it more difficult and dangerous to diagnose problems.[3]

The task of writing drivers thus usually falls to software engineers or computer engineers who work for hardware-development companies. This is because they have better information than most outsiders about the design of their hardware. Moreover, it was traditionally considered in the hardware manufacturer's interest to guarantee that their clients can use their hardware in an optimal way. Typically, the Logical Device Driver (LDD) is written by the operating system vendor, while the Physical Device Driver (PDD) is implemented by the device vendor. However, in recent years, non-vendors have written numerous device drivers for proprietary devices, mainly for use with free and open source operating systems. In such cases, it is important that the hardware manufacturer provide information on how the device communicates. Although this information can instead be learned by reverse engineering, this is much more difficult with hardware than it is with software.

Windows uses a combination of driver and minidriver, where the full class/port driver is provided with the operating system, and miniclass/miniport drivers are developed by vendors and implement hardware- or function-specific subset of the full driver stack.[4] Miniport model is used by NDIS, WDM, WDDM, WaveRT, StorPort, WIA, and HID drivers; each of them uses device-specific APIs and still requires the developer to handle tedious device management tasks.

Microsoft has attempted to reduce system instability due to poorly written device drivers by creating a new framework for driver development, called Windows Driver Frameworks (WDF). This includes User-Mode Driver Framework (UMDF) that encourages development of certain types of drivers—primarily those that implement a message-based protocol for communicating with their devices—as user-mode drivers. If such drivers malfunction, they do not cause system instability. The Kernel-Mode Driver Framework (KMDF) model continues to allow development of kernel-mode device drivers but attempts to provide standard implementations of functions that are known to cause problems, including cancellation of I/O operations, power management, and plug-and-play device support.

Apple has an open-source framework for developing drivers on macOS, called I/O Kit.

In Linux environments, programmers can build device drivers as parts of the kernel, separately as loadable modules, or as user-mode drivers (for certain types of devices where kernel interfaces exist, such as for USB devices). Makedev includes a list of the devices in Linux, including ttyS (terminal), lp (parallel port), hd (disk), loop, and sound (these include mixer, sequencer, dsp, and audio).[5]

Microsoft Windows .sys files and Linux .ko files can contain loadable device drivers. The advantage of loadable device drivers is that they can be loaded only when necessary and then unloaded, thus saving kernel memory.

Privilege levels

[edit]Depending on the operating system, device drivers may be permitted to run at various different privilege levels. The choice of which level of privilege the drivers are in is largely decided by the type of kernel an operating system uses. An operating system that uses a monolithic kernel, such as the Linux kernel, will typically run device drivers with the same privilege as all other kernel objects. By contrast, a system designed around microkernel, such as Minix, will place drivers as processes independent from the kernel but that use it for essential input-output functionalities and to pass messages between user programs and each other.[6] On Windows NT, a system with a hybrid kernel, it is common for device drivers to run in either kernel-mode or user-mode.[7]

The most common mechanism for segregating memory into various privilege levels is via protection rings. On many systems, such as those with x86 and ARM processors, switching between rings imposes a performance penalty, a factor that operating system developers and embedded software engineers consider when creating drivers for devices which are preferred to be run with low latency, such as network interface cards. The primary benefit of running a driver in user mode is improved stability since a poorly written user-mode device driver cannot crash the system by overwriting kernel memory.[8]

Applications

[edit]Because of the diversity of modern[update] hardware and operating systems, drivers operate in many different environments.[9] Drivers may interface with:

- Printers

- Video adapters

- Network cards

- Sound cards

- PC chipsets

- Power and battery management

- Local buses of various sorts—in particular, for bus mastering on modern systems

- Low-bandwidth I/O buses of various sorts (for pointing devices such as mice, keyboards, etc.)

- Computer storage devices such as hard disk, CD-ROM, and floppy disk buses (ATA, SATA, SCSI, SAS)

- Implementing support for different file systems

- Image scanners

- Digital cameras

- Digital terrestrial television tuners

- Radio frequency communication transceiver adapters for wireless personal area networks as used for short-distance and low-rate wireless communication in home automation, (such as example Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), Thread, Zigbee, and Z-Wave).

- IrDA adapters

Common levels of abstraction for device drivers include:

- For hardware:

- Interfacing directly

- Writing to or reading from a device control register

- Using some higher-level interface (e.g. Video BIOS)

- Using another lower-level device driver (e.g. file system drivers using disk drivers)

- Simulating work with hardware, while doing something entirely different[10]

- For software:

- Allowing the operating system direct access to hardware resources

- Implementing only primitives

- Implementing an interface for non-driver software (e.g. TWAIN)

- Implementing a language, sometimes quite high-level (e.g. PostScript)

So choosing and installing the correct device drivers for given hardware is often a key component of computer system configuration.[11]

Virtual device drivers

[edit]Virtual device drivers represent a particular variant of device drivers. They are used to emulate a hardware device, particularly in virtualization environments, for example when a guest operating system is run on a Xen host. Instead of enabling the guest operating system to dialog with hardware, virtual device drivers take the opposite role and emulates a piece of hardware, so that the guest operating system and its drivers running inside a virtual machine can have the illusion of accessing real hardware. Attempts by the guest operating system to access the hardware are routed to the virtual device driver in the host operating system as e.g., function calls. The virtual device driver can also send simulated processor-level events like interrupts into the virtual machine.

Virtual devices may also operate in a non-virtualized environment. For example, a virtual network adapter is used with a virtual private network, while a virtual disk device is used with iSCSI. A good example for virtual device drivers can be Daemon Tools.

There are several variants of virtual device drivers, such as VxDs, VLMs, and VDDs.

Open source drivers

[edit]- Graphics device driver

- Printers: CUPS

- RAIDs: CCISS[12] (Compaq Command Interface for SCSI-3 Support[13])

- Scanners: SANE

- Video: Vidix, Direct Rendering Infrastructure

Solaris descriptions of commonly used device drivers:

- fas: Fast/wide SCSI controller

- hme: Fast (10/100 Mbit/s) Ethernet

- isp: Differential SCSI controllers and the SunSwift card

- glm: (Gigabaud Link Module[14]) UltraSCSI controllers

- scsi: Small Computer Serial Interface (SCSI) devices

- sf: soc+ or social Fiber Channel Arbitrated Loop (FCAL)

- soc: SPARC Storage Array (SSA) controllers and the control device

- social: Serial optical controllers for FCAL (soc+)

APIs

[edit]- Windows Display Driver Model (WDDM) – the graphic display driver architecture for Windows Vista and later.

- Unified Audio Model (UAM)[15]

- Windows Driver Foundation (WDF)

- Declarative Componentized Hardware (DCH) - Universal Windows Platform driver[16]

- Windows Driver Model (WDM)

- Network Driver Interface Specification (NDIS) – a standard network card driver API

- Advanced Linux Sound Architecture (ALSA) – the standard Linux sound-driver interface

- Scanner Access Now Easy (SANE) – a public-domain interface to raster-image scanner-hardware

- Installable File System (IFS) – a filesystem API for IBM OS/2 and Microsoft Windows NT

- Open Data-Link Interface (ODI) – network card API similar to NDIS

- Uniform Driver Interface (UDI) – a cross-platform driver interface project

- Dynax Driver Framework (dxd) – C++ open source cross-platform driver framework for KMDF and IOKit[17]

Identifiers

[edit]A device on the PCI bus or USB is identified by two IDs which consist of two bytes each. The vendor ID identifies the vendor of the device. The device ID identifies a specific device from that manufacturer/vendor.

A PCI device has often an ID pair for the main chip of the device, and also a subsystem ID pair that identifies the vendor, which may be different from the chip manufacturer.

Security

[edit]Computers often have many diverse and customized device drivers running in their operating system kernel which often contain various bugs and vulnerabilities, making them a target for exploits.[18] A Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver (BYOVD) attacker installs any signed, old third-party driver with known vulnerabilities that allow malicious code to be inserted into the kernel.[19] Drivers that may be vulnerable include those for WiFi and Bluetooth,[20][21] gaming/graphics drivers,[22] and drivers for printers.[23]

There is a lack of effective kernel vulnerability detection tools, especially for closed-source operating systems such as Microsoft Windows[24] where the source code of the device drivers is mostly proprietary and not available to examine,[25] and drivers often have many privileges.[26][27][28][29]

A group of security researchers considers the lack of isolation as one of the main factors undermining kernel security,[30] and published an isolation framework to protect operating system kernels, primarily the monolithic Linux kernel whose drivers they say get ~80,000 commits per year.[31][32]

An important consideration in the design of a kernel is the support it provides for protection from faults (fault tolerance) and from malicious behaviours (security). These two aspects are usually not clearly distinguished, and the adoption of this distinction in the kernel design leads to the rejection of a hierarchical structure for protection.[33]

The mechanisms or policies provided by the kernel can be classified according to several criteria, including: static (enforced at compile time) or dynamic (enforced at run time); pre-emptive or post-detection; according to the protection principles they satisfy (e.g., Denning[34][35]); whether they are hardware supported or language based; whether they are more an open mechanism or a binding policy; and many more.See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "What is all device driver?". WhatIs.com. TechTarget. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ EMC Education Services (2010). Information Storage and Management: Storing, Managing, and Protecting Digital Information. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470618332. Archived from the original on 2021-02-13. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- ^ Burke, Timothy (1995). Writing device drivers: tutorial and reference. Digital Press. ISBN 9781555581411. Archived from the original on 2021-01-26. Retrieved 2016-08-05.

- ^ "Choosing a driver model". Microsoft. Retrieved 2021-03-30.

- ^ "MAKEDEV — Linux Command — Unix Command". Linux.about.com. 2009-09-11. Archived from the original on 2009-04-30. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew; Woodhull, Albert (2006). Operating Systems, Design and Implementation (3rd. ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Pretence Hall. p. 256. ISBN 0-13-142938-8.

- ^ Yosifovich, Pavel; Ionescu, Alex; Russinovich, Mark; Solomon, David (2017). Windows Internals, Part 1 (Seventh ed.). Redmond, Washington: Microsoft Press. ISBN 978-0-7356-8418-8.

- ^ "Introduction to the User-Mode Driver Framework (UMDF)". Microsoft. 2006-10-10. Archived from the original on 2010-01-07. Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ^ Deborah Morley (2009). Understanding Computers 2009: Today and Tomorrow. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9780324830132. Archived from the original on 2021-06-09. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- ^ Computer Peripherals and Interfaces. Technical Publications Pune. January 2008. pp. 5–8. ISBN 978-8184314748. Retrieved 2016-05-03.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "What are Device Drivers and why do we need them?". drivers.com. April 17, 2015. Archived from the original on November 20, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "CCISS". SourceForge. 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-08-21. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

Drivers for the HP (previously Compaq) Smart Array controllers which provide hardware RAID capability.

- ^ Russell, Steve; et al. (2003-10-21). Abbreviations and acronyms. IBM International Technical Support Organization. p. 207. ISBN 0-7384-2684-9. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)[permanent dead link] - ^ "US Patent 5969841 - Gigabaud link module with received power detect signal". PatentStorm LLC. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2009-09-08.

An improved Gigabaud Link Module (GLM) is provided for performing bi-directional data transfers between a host device and a serial transfer medium.

- ^ "Unified Audio Model (Windows CE 5.0)". Microsoft Developer Network. 14 September 2012. Archived from the original on 2017-06-22. Retrieved 2016-09-19.

- ^ Dell US. "What are DCH drivers and why do you need to know about them? | Dell US". www.dell.com. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ^ "dxd - dynax driver framework: Main Page". dxd.dynax.at. Archived from the original on 2016-05-29. Retrieved 2016-09-19.

- ^ Talebi, Seyed Mohammadjavad Seyed; Tavakoli, Hamid; Zhang, Hang; Zhang, Zheng; Sani, Ardalan Amiri; Qian, Zhiyun (2018). Charm: Facilitating Dynamic Analysis of Device Drivers of Mobile Systems. pp. 291–307. ISBN 9781939133045. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Goodin, Dan (14 October 2022). "How a Microsoft blunder opened millions of PCs to potent malware attacks". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 8 November 2022. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Ridley, Jacob (9 February 2022). "You're going to want to update your Wi-Fi and Bluetooth drivers today". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ "Wireless 'BlueBorne' Attacks Target Billions of Bluetooth Devices". threatpost.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Spadafora, Anthony (12 January 2022). "Installing gaming drivers might leave your PC vulnerable to cyberattacks". TechRadar. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ "HP patches vulnerable driver lurking in printers for 16 years". ZDNET. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Pan, Jianfeng; Yan, Guanglu; Fan, Xiaocao (2017). Digtool: A {Virtualization-Based} Framework for Detecting Kernel Vulnerabilities. USENIX Association. pp. 149–165. ISBN 9781931971409. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ King, Bertel (18 June 2022). "Closed Source vs. Open Source Hardware Drivers: Why It Matters". MUO. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Branscombe, Mary (7 April 2022). "How Microsoft blocks vulnerable and malicious drivers in Defender, third-party security tools and in Windows 11". TechRepublic. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Goodin, Dan (5 October 2022). "No fix in sight for mile-wide loophole plaguing a key Windows defense for years". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Davenport, Corbin. ""Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver" Attacks Are Breaking Windows". How-To Geek. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ "Windows 10 Security Alert: Vulnerabilities Found in Over 40 Drivers". BleepingComputer. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ "Fine-grained kernel isolation". mars-research.github.io. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Fetzer, Mary. "Automatic device driver isolation protects against bugs in operating systems". Pennsylvania State University via techxplore.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Huang, Yongzhe; Narayanan, Vikram; Detweiler, David; Huang, Kaiming; Tan, Gang; Jaeger, Trent; Burtsev, Anton (2022). "KSplit: Automating Device Driver Isolation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Wulf 1974 pp.337–345

- ^ Denning 1976

- ^ Swift 2005, p.29 quote: "isolation, resource control, decision verification (checking), and error recovery."

External links

[edit]Device driver

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A device driver is a specialized computer program that operates or controls a particular type of device attached to a computer, acting as a translator between the operating system and the hardware.[2][1] This software enables the operating system to communicate with hardware components, such as printers, graphics cards, or storage devices, by abstracting the low-level details of hardware interaction into standardized interfaces.[11] Without device drivers, applications and the operating system would need direct knowledge of each device's specific protocols and registers, which varies widely across manufacturers and models.[12] Device drivers typically include key components such as initialization routines to set up the device upon system startup or loading, interrupt handlers to manage asynchronous events from the hardware, and I/O control functions to handle data transfer operations like reading or writing.[12][13] These elements allow the driver to respond efficiently to hardware signals and requests, ensuring seamless integration within the operating system's kernel or user space.[14] In contrast to firmware, which consists of low-level software embedded directly in the hardware device itself and executed independently of the host operating system, device drivers are OS-specific programs dynamically loaded at runtime to facilitate host-device communication.[15][16] Firmware handles basic device operations autonomously, while drivers provide the bridge for higher-level OS commands and resource management.[17] The term "device driver" originated in the late 1960s, derived from the idea of software that "drives" or directs hardware operation.[18] This evolution reflected the growing complexity of computer peripherals and the need for modular software abstractions.[19]Purpose

Device drivers serve as essential intermediaries that abstract the complexities of hardware-specific details from the operating system kernel, allowing it to interact with diverse devices through a standardized interface.[8] By translating generic I/O instructions into device-specific commands and protocols, they enable the kernel to communicate effectively without needing to understand the intricacies of each hardware implementation.[2] Additionally, device drivers manage critical resource allocation, such as memory buffers for data transfer and interrupt handling to respond to hardware events in a timely manner.[6] This abstraction layer promotes operating system portability, permitting a single OS kernel to support a wide array of hardware configurations—including peripherals from different manufacturers—without requiring modifications to the core kernel code.[20] For instance, the same Linux kernel can accommodate various graphics cards or storage devices across multiple architectures by loading appropriate drivers at runtime. Device drivers also handle error detection and recovery, monitoring hardware status to identify failures like read/write errors or connection losses, and reporting them to the OS for appropriate action, such as retrying operations or notifying users.[12] They manage power states and configuration changes, transitioning devices between active, low-power, or suspended modes to optimize energy use while ensuring seamless adaptation to dynamic hardware environments, like hot-plugging USB devices.[21] Without these drivers, the operating system would be unable to interpret signals from peripherals such as printers or network cards, rendering the hardware unusable.[8]Basic Operation

Device drivers operate as intermediaries between the operating system and hardware devices, facilitating communication through a structured workflow. When an application issues a system call—such as open, read, write, or close—the operating system kernel routes the request to the appropriate device driver. The driver translates these high-level requests into low-level hardware-specific commands, which are then sent to the device controller for execution on the physical device. Upon completion, the hardware generates a response, which the driver processes and relays back to the operating system as data or status information, enabling seamless integration of device functionality into user applications.[22][23] Responses from hardware are managed either through polling, where the driver periodically queries the device status, or more efficiently via interrupts, which signal the completion of operations asynchronously. To handle interrupts, device drivers register interrupt service routines (ISRs) with the kernel; these routines are automatically invoked by the hardware interrupt controller when an event occurs, such as data arrival or error detection. The ISR quickly acknowledges the interrupt, performs minimal processing to avoid delaying other system activities, and often schedules deferred work in a bottom-half handler to manage the event fully without holding interrupt context. This mechanism ensures timely responses to hardware events while minimizing CPU overhead.[24][25] For input/output (I/O) operations, device drivers provide standardized read and write functions that abstract the underlying hardware complexity, allowing the operating system to perform data transfers consistently across devices. In scenarios involving large data volumes, such as disk or network transfers, drivers leverage Direct Memory Access (DMA) to enhance efficiency; the driver configures the DMA controller with parameters including the operation type, memory address, and transfer size, enabling the device to move data directly between memory and the device without CPU involvement. Upon transfer completion, the DMA controller issues an interrupt to the driver, which then validates the operation and notifies the operating system. This approach reduces CPU utilization and improves system throughput for high-bandwidth I/O.[26][27] Throughout a device's lifecycle, drivers maintain state management to ensure reliable operation, encompassing initialization, configuration, and shutdown phases. During system startup or device attachment, the driver executes an initialization sequence to probe the hardware, allocate necessary kernel resources like memory buffers and interrupt lines, and configure device registers for operational modes. Ongoing configuration adjusts parameters such as transfer rates or buffering based on runtime needs, while shutdown sequences—triggered by system halt or device removal—reverse these steps by releasing resources, flushing pending operations, and powering down the hardware safely to prevent data loss or corruption. These phases are critical for maintaining device stability and compatibility within the operating system environment.[28][29]History

Early Development

The origins of device drivers emerged in the 1950s within batch-processing systems, such as the IBM 701, where rudimentary software routines written in assembly language directly controlled peripherals including magnetic tape drives and punch card readers.[30] These early computers lacked formal operating systems, requiring programmers to book entire machines and manage hardware interactions manually via console switches, lights, and polled I/O routines to load programs from cards or tapes and output results.[30] Magnetic tape, introduced with the IBM 701 in 1952, marked a significant advancement by enabling faster data transfer at 100 characters per inch and 70 inches per second, replacing slower punched card stacks and allowing off-line preparation of jobs for efficiency.[31] In the 1960s, innovations in time-sharing systems advanced device driver concepts toward modularity, with Multics—initiated in 1965 as a collaboration between MIT, Bell Labs, and General Electric—incorporating dedicated support for peripherals and terminals within its virtual memory architecture.[32] Early UNIX, developed at Bell Labs starting in 1969, further refined this approach by designing drivers as reusable, modular components integrated into the kernel, facilitating interactions with devices like terminals through a unified file system interface that treated hardware as files.[33] Key contributions came from Bell Labs researchers Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie, who emphasized simplicity and reusability in UNIX driver design to support multi-user environments on limited hardware like the PDP-7 and PDP-11 minicomputers.[34] A primary challenge in these early developments was the reliance on manual assembly language coding for hardware-specific control, without standardized interfaces, which demanded deep knowledge of machine architecture and often led to inefficient, error-prone implementations due to memory constraints and direct register manipulation.[30] Programmers had to optimize every instruction for performance, as higher-level abstractions were absent, making driver development labor-intensive and tightly coupled to particular hardware configurations.[35]Evolution in Operating Systems

In the UNIX and Linux operating systems, device drivers evolved toward modularity in the 1990s to enhance kernel flexibility without requiring full recompilation. Loadable kernel modules (LKMs) were introduced in Linux kernel version 1.1.85 in January 1995, allowing dynamic loading of driver code at runtime to support hardware-specific functionality.[36] This approach built on earlier UNIX traditions but standardized in Linux through tools like insmod, which inserts compiled module objects directly into the running kernel, enabling on-demand driver activation for peripherals such as network interfaces and storage devices.[37] By the late 1990s, this modular system became a cornerstone of Linux distributions, facilitating easier maintenance and hardware support in evolving server and desktop environments.[38] Windows device drivers underwent significant standardization starting with the transition from 16-bit to 32-bit architectures. In Windows 3.x (1990–1992), Virtual Device Drivers (VxDs) provided protected-mode extensions for MS-DOS compatibility, handling interrupts and I/O in a virtualized manner primarily through assembly language.[39] The Windows Driver Model (WDM) marked a pivotal shift, introduced with Windows 98 in 1998 and fully realized in Windows 2000 in 2000, unifying driver interfaces for USB, Plug and Play, and power management to reduce vendor-specific code and improve stability across hardware. Building on WDM, Microsoft developed the Windows Driver Frameworks in the mid-2000s: the Kernel-Mode Driver Framework (KMDF) debuted with Windows Vista in 2006 to simplify kernel-level development by abstracting common tasks like power and I/O handling, while the User-Mode Driver Framework (UMDF), also from 2006, enabled safer user-space execution for less critical devices, minimizing crash risks.[40] These frameworks persist in modern Windows versions, promoting binary compatibility and reducing development complexity.[41] Apple's macOS, derived from NeXTSTEP and BSD UNIX, adopted an object-oriented paradigm for drivers with the IOKit framework, introduced in 2001 alongside Mac OS X 10.0 (now macOS). IOKit leverages C++ classes to model device trees and handle matching, powering, and interrupt management in a modular, extensible way that abstracts hardware details for developers.[42] This design facilitated rapid adaptation to new peripherals like USB and FireWire, integrating seamlessly with the XNU kernel and supporting both kernel extensions and user-space interactions.[43] IOKit's influence endures, evolving to incorporate security features like code signing in later macOS releases. By the 2020s, device driver evolution has trended toward "driverless" architectures, reducing reliance on traditional kernel modules in containerized and virtualized environments. In Linux, extended Berkeley Packet Filter (eBPF) programs, enhanced since kernel 4.4 in 2015 but maturing through 2025, enable safe, in-kernel execution of user-defined code for networking and observability without loading full drivers, powering tools like Cilium for container orchestration in Kubernetes.[44] This shift supports scalable, secure microservices by offloading packet processing to eBPF hooks, minimizing overhead in cloud-native setups.[45] Complementing this, virtio drivers—a paravirtualized standard originating in 2006 for KVM/QEMU—have gained prominence for efficient I/O in virtual machines, with updates like version 2.3 in 2025 extending support to Windows Server 2025 and enhancing performance in hybrid cloud infrastructures.[46] These advancements reflect a broader push toward abstraction layers that prioritize portability and security over hardware-specific code.[47]Architecture and Design

Kernel-Mode vs User-Mode Drivers

Kernel-mode drivers execute in the privileged kernel space of the operating system, sharing a single virtual address space with core OS components and enabling direct access to hardware resources such as memory and I/O ports. This direct access facilitates efficient, low-level operations but lacks isolation, meaning a bug or crash in a kernel-mode driver can corrupt system data or halt the entire operating system, as seen in the Blue Screen of Death (BSOD) errors triggered by faulty kernel drivers in Windows.[4][48] In contrast, user-mode drivers operate within isolated user-space processes, each with its own private virtual address space, preventing direct hardware interaction and requiring mediated communication with the kernel via system calls or frameworks. This isolation enhances system stability, as a failure in a user-mode driver typically affects only its hosting process rather than the kernel, and simplifies debugging since standard user-mode tools can be used without risking OS crashes. Examples include the User-Mode Driver Framework (UMDF) in Windows, which supports non-critical devices through a host process that manages interactions with kernel-mode components.[4][49] The key trade-offs center on performance and reliability: kernel-mode drivers provide superior efficiency for latency-sensitive tasks, such as real-time I/O handling, due to minimal overhead in hardware access, but they introduce higher security risks from potential privilege escalation or instability. User-mode drivers prioritize safety and ease of development by containing faults within user space, though they incur context-switching costs that can reduce performance for high-throughput operations.[4][49] Representative examples illustrate these distinctions; network interface controllers often rely on kernel-mode drivers to manage high-speed packet processing and interrupt handling for optimal throughput, while USB-based scanners and printers commonly use user-mode drivers like those in UMDF to interface safely with applications without compromising system integrity.[7][50]Device Driver Models

Device driver models provide standardized frameworks that define how drivers interact with the operating system kernel, hardware devices, and other software components, ensuring compatibility, modularity, and ease of maintenance across diverse hardware ecosystems. These models abstract low-level hardware details, allowing developers to focus on device-specific logic while leveraging common interfaces for resource management, power handling, and plug-and-play functionality. By enforcing structured layering—such as bus drivers, functional drivers, and filters—they facilitate the development of drivers that can operate consistently across operating system versions and hardware platforms. The Windows Driver Model (WDM), introduced with Windows 98 in 1998 and fully realized in Windows 2000, establishes a layered architecture for kernel-mode drivers that promotes source-code compatibility across Windows versions.[51] In this model, drivers are organized into functional components: bus drivers enumerate and manage hardware buses, port drivers (or class drivers) provide common functionality for device classes, and miniport drivers handle device-specific operations, enabling a modular stack where higher-level drivers interact with lower-level ones via standardized I/O request packets (IRPs).[52] This structure supports features like power management and Plug and Play, reducing the need for redundant code in multi-vendor environments.[51] Building on WDM, the Windows Driver Frameworks (WDF), introduced in the mid-2000s, provide a higher-level abstraction for developing both kernel-mode and user-mode drivers, recommended for new development as of 2025. The Kernel-Mode Driver Framework (KMDF) version 1.0 was released in December 2005 for Windows XP SP2 and later, while the User-Mode Driver Framework (UMDF) followed in 2006 with Windows Vista. WDF simplifies driver creation by handling common tasks such as I/O processing, power management, and Plug and Play through object-oriented interfaces, reducing boilerplate code and improving reliability while maintaining binary compatibility across Windows versions from XP onward.[40] In Linux, the device driver model, integrated into the kernel since version 2.5 and stabilized in 2.6, uses a hierarchical representation of devices, buses, and drivers to enable dynamic discovery and management.[53] Central to this model is sysfs, a virtual filesystem that exposes device attributes, topology, and attributes in a structured directory hierarchy under /sys, allowing userspace tools to query and configure hardware without direct kernel modifications.[54] Hotplug support is handled through uevents, kernel-generated notifications sent via netlink sockets to userspace daemons like udev, which respond by creating device nodes, loading modules, or adjusting permissions based on predefined rules.[55] This event-driven approach ensures seamless integration of removable or dynamically detected devices, such as USB peripherals.[56] Other notable models include the Network Driver Interface Specification (NDIS) in Windows, which standardizes networking drivers by abstracting network interface cards (NICs) through miniport, protocol, and filter drivers, allowing protocol stacks like TCP/IP to bind uniformly regardless of hardware.[57] NDIS, originating in early Windows NT versions and evolving through NDIS 6.x in Windows Vista and later, supports features like offloading and virtualization for high-performance networking.[58] Similarly, Apple's IOKit framework, introduced with Mac OS X 10.0 in 2001, employs an object-oriented, C++-based architecture using IOService and IONode subclasses to model devices as a publish-subscribe tree, where drivers match and attach to hardware via property dictionaries for automatic configuration and hot-swapping.[42] IOKit emphasizes runtime loading of kernel extensions (KEXTs) and user-kernel bridging for safe access.[43] These models collectively enhance reusability by encapsulating common operations in base classes or interfaces, abstracting hardware variations to minimize vendor-specific implementations, and streamlining updates through modular components that can be independently developed and tested. For instance, a miniport driver in WDM or NDIS can reuse the OS's power management logic without reimplementing it, reducing development time and errors while supporting diverse hardware ecosystems.[59] This abstraction layer also improves system stability, as changes in underlying hardware require only targeted driver updates rather than widespread code revisions.[60]Application Programming Interfaces (APIs)

Device drivers interact with the operating system and applications through well-defined application programming interfaces (APIs), which provide standardized mechanisms for issuing commands, transferring data, and managing device states. These APIs are essential for abstracting hardware complexities, ensuring that higher-level software can operate devices without direct hardware manipulation. In kernel space, APIs facilitate communication between the operating system kernel and driver modules, while user-space APIs enable applications to access devices securely without elevated privileges. Kernel-level APIs are typically synchronous or semi-synchronous and handle low-level I/O operations. In UNIX-like systems, the ioctl() system call serves as a primary interface for device control, allowing applications to perform device-specific operations such as configuring parameters or querying status that cannot be handled by standard read() and write() calls. For instance, ioctl() manipulates underlying device parameters for special files, supporting a wide range of commands defined by the driver.[61] In Windows, I/O Request Packets (IRPs) represent the core kernel API for communication between the I/O manager and drivers, encapsulating requests like read, write, or device control operations in a structured packet that propagates through the driver stack.[62] IRPs enable the operating system to manage asynchronous I/O flows while providing drivers with necessary context, such as buffer locations and completion routines.[63] User-space APIs bridge applications and drivers without requiring kernel-mode access, enhancing security and portability. A prominent example is libusb, a cross-platform library that allows user applications to communicate directly with USB devices via a standardized API, bypassing the need for custom kernel drivers in many cases. libusb provides functions for device enumeration, configuration, and data transfer, operating entirely in user mode on platforms like Linux, Windows, and macOS.[64] This approach is particularly useful for non-privileged applications interacting with hot-pluggable devices. Standards such as POSIX ensure API portability across compliant operating systems, promoting consistent device I/O behaviors. POSIX defines interfaces like open(), read(), write(), and ioctl() for accessing device files, enabling source-code portability for applications and drivers that adhere to these specifications.[65] Additionally, Plug and Play (PnP) APIs support dynamic device detection and resource allocation; in Windows, the PnP manager uses IRP-based interfaces to notify drivers of hardware changes, such as insertions or removals, facilitating automatic configuration without manual intervention.[66] In Linux, PnP mechanisms integrate with kernel APIs to enumerate and assign resources to legacy or modern devices.[67] Over time, APIs have evolved toward asynchronous models to address performance bottlenecks in high-throughput scenarios. Introduced in Linux kernel 5.1 in 2019, io_uring represents a shift to ring-buffer-based asynchronous I/O, allowing efficient submission and completion of multiple requests without blocking system calls, which improves scalability for networked and storage devices compared to traditional POSIX APIs.[68][69] This evolution reduces context switches and enhances throughput, influencing modern driver designs for better handling of concurrent operations.Development Process

Tools and Languages

Device drivers are predominantly developed using the C programming language due to its ability to provide low-level hardware access and portability across operating systems while maintaining efficiency in kernel environments.[2] This choice stems from C's close alignment with machine code, enabling direct manipulation of hardware registers and memory without the overhead of higher-level abstractions. In specific frameworks, such as Apple's IOKit, C++ is employed to leverage object-oriented features for building modular driver components, including inheritance and polymorphism for handling device families.[70] Assembly language is occasionally used for performance-critical sections, such as interrupt handlers or optimized I/O routines, where fine-grained control over processor instructions is essential to minimize latency.[2] For Linux kernel drivers, the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC) serves as the primary compiler, cross-compiling modules against the kernel headers to ensure compatibility with the target architecture.[71] Debugging relies on tools like KGDB, which integrates with GDB to enable source-level debugging of kernel code over serial or network connections, allowing developers to set breakpoints and inspect variables in a running kernel. Windows driver development utilizes Microsoft Visual Studio integrated with the Windows Driver Kit (WDK), which provides templates, libraries, and build environments tailored for kernel-mode and user-mode drivers.[72] For debugging Windows drivers, WinDbg offers advanced capabilities, including kernel-mode analysis, live debugging via KD protocol, and crash dump examination.[73] Build systems for Linux drivers typically involve Kbuild Makefiles, which automate compilation by incorporating kernel configuration and generating loadable modules (.ko files) through commands likemake modules.[71] CMake is increasingly adopted for out-of-tree driver projects, offering cross-platform configuration and dependency management while invoking the kernel's build system for final linking. On Windows, INF files define the driver package structure, specifying hardware IDs, file copies, registry entries, and signing requirements to facilitate installation via PnP Manager.[74]

Since 2022, Rust has been integrated into the Linux kernel as an experimental language for driver development, aiming to enhance memory safety and reduce vulnerabilities like buffer overflows common in C code.[75] By 2025, Rust support in the Linux kernel has advanced, with the inclusion of the experimental Rust-based NOVA driver for NVIDIA GPUs (Turing series and newer) in Linux kernel 6.15 (released May 25, 2025), and ongoing development of a Rust NVMe driver, though neither is yet production-ready as of November 2025.[76][77] This adoption leverages Rust's borrow checker to enforce safe concurrency and ownership, particularly beneficial for complex drivers handling concurrent I/O operations.[78]

Testing and Debugging

Testing device drivers involves a range of approaches to verify functionality without always requiring physical hardware, beginning with unit tests that isolate driver components using mock hardware simulations to check individual functions like interrupt handling or data transfer routines.[79] These mocks replace hardware interactions with software stubs, allowing developers to validate logic under controlled conditions, such as simulating device registers or I/O operations. Integration tests then combine these components, often leveraging emulators like QEMU to mimic full system environments and test driver interactions with the kernel or other modules.[80] For instance, QEMU's QTest framework enables injecting stimuli into device models to assess emulation accuracy and driver responses. Stress testing further evaluates concurrency by subjecting drivers to high loads, such as simultaneous interrupts or multiple thread accesses, to uncover race conditions or resource exhaustion.[81] Debugging device drivers relies on specialized techniques due to the kernel's constrained environment, starting with kernel loggers that capture runtime events for post-analysis. In Linux, the dmesg command retrieves messages from the kernel ring buffer, revealing driver errors like failed initializations or panic traces.[82] Breakpoints in kernel debuggers, such as WinDbg for Windows or KGDB for Linux, allow pausing execution at critical points to inspect variables and stack traces during live sessions. Static analysis tools complement these by scanning source code for potential flaws, like null pointer dereferences or locking inconsistencies, without running the driver; Microsoft's Static Driver Verifier, for example, applies formal methods to verify API compliance against predefined rules.[83] Key challenges in testing and debugging arise from hardware dependencies and timing sensitivities, particularly reproducing issues tied to specific physical devices, as emulators may not fully capture vendor-unique behaviors or firmware interactions.[84] Non-deterministic interrupts exacerbate this, where event interleavings from asynchronous hardware signals create rare race conditions that are hard to trigger consistently in simulated setups, often requiring extensive randomized testing to surface defects. Standards like Microsoft's WHQL certification ensure driver reliability and compatibility through rigorous validation in the Windows Hardware Lab Kit, encompassing automated tests for system stability, power management, and device enumeration across multiple hardware configurations.[85] Passing WHQL grants a digital signature, allowing seamless installation on Windows systems and affirming adherence to compatibility guidelines that prevent conflicts with core OS components.Types of Device Drivers

Physical Device Drivers

Physical device drivers are specialized software components within an operating system that enable direct interaction with tangible hardware, translating high-level OS commands into low-level hardware-specific operations. Unlike abstracted interfaces, these drivers manage the physical signaling and data flow to and from devices, ensuring reliable communication without intermediate emulation layers. This direct hardware engagement is essential for peripherals that require precise timing and resource allocation, such as those connected via dedicated buses or ports.[12] The scope of physical device drivers includes a variety of hardware categories, notably graphics processing units (GPUs) for accelerated visual computations, storage devices like hard disk drives (HDDs) and solid-state drives (SSDs) interfaced through standards such as AHCI for SATA or NVMe for PCIe-based connections, and sensors for capturing environmental data like temperature, motion, or light. For storage, AHCI drivers implement the Serial ATA protocol to handle command issuance, data transfer, and error recovery across SATA ports, supporting native command queuing for efficient HDD and SSD operations. Sensor drivers, often built on frameworks like Linux's Industrial I/O (IIO) subsystem, acquire raw data from hardware via protocols such as I2C or SPI, providing buffered readings for applications. Key characteristics of physical device drivers involve managing I/O ports for register access—either through memory-mapped I/O or port-mapped I/O—and implementing bus protocols like PCIe for high-bandwidth transfers in GPUs and NVMe SSDs, or USB for plug-and-play peripherals. These drivers also incorporate power management features, integrating with ACPI to negotiate device states (e.g., D0 active to D3 low-power), monitoring dependencies, and coordinating transitions to balance performance and energy efficiency. In the 2020s, NVMe SSD drivers have advanced with multi-queue optimizations, creating per-core submission and completion queues to exploit SSD parallelism and reduce CPU overhead, as demonstrated in Linux kernel implementations that support up to 64K queues per device for improved I/O throughput.[86][87][88][89] Representative examples illustrate these functions: NVIDIA and AMD graphics drivers directly control GPU hardware for rendering acceleration by submitting rendering commands to the GPU's command processor, allocating video memory, and handling interrupts for frame completion, enabling features like hardware-accelerated 3D graphics and video decoding. Realtek audio drivers interface with high-definition audio (HD Audio) codecs, such as the ALC892, to manage DAC/ADC channels for multi-channel playback and recording, processing digital signals through the codec's DSP for effects like surround sound. These drivers exemplify the hardware-specific optimizations that physical device drivers provide across diverse peripherals.[90][91]Virtual Device Drivers

Virtual device drivers simulate hardware interfaces within software environments, enabling efficient resource sharing among multiple applications or virtual machines without direct access to physical hardware. In early Windows operating systems, such as Windows 3.x and Windows 9x, Virtual eXtended Drivers (VxDs) served this purpose by running in kernel mode as part of the Virtual Machine Manager (VMM), allowing multitasking applications to virtualize devices like ports, disks, and displays while preventing conflicts in the 386 enhanced mode.[92] These drivers operated at ring 0 in a 32-bit flat model, managing system resources for cooperative multitasking environments where DOS sessions ran alongside Windows applications.[93] In modern virtualization, virtual device drivers have evolved into paravirtualized implementations, where guest operating systems use specialized drivers to communicate directly with the hypervisor, bypassing full hardware emulation. A prominent example is the virtio standard, which provides paravirtualized interfaces for block storage, networking, and other I/O devices in virtual machines (VMs) hosted on hypervisors like KVM.[94] This approach presents a simplified, hypervisor-aware interface to the guest OS, optimizing data transfer through shared memory rings rather than simulated hardware traps.[95] The primary benefit of virtual device drivers lies in performance enhancement for virtualized workloads, as they reduce the overhead of full device emulation by enabling semi-direct I/O paths that achieve near bare-metal throughput and latency. For instance, paravirtualized drivers can decrease guest I/O latency and increase network or storage bandwidth to levels comparable to physical hardware, minimizing CPU cycles wasted on trap-and-emulate cycles in hypervisors.[95] Specific examples include VMware Tools drivers, which provide paravirtualized components like the VMXNET3 network interface card (NIC) driver for high-throughput networking and the paravirtual SCSI (PVSCSI) driver for optimized storage access in vSphere VMs, improving overall resource utilization and application responsiveness.[96] Similarly, in the Xen hypervisor, frontend drivers in guest domains pair with backend drivers in the host domain to manage virtual devices, such as para-virtualized display or block devices, using a split-driver model over the XenBus inter-domain communication channel for efficient I/O virtualization.[97][98] By 2025, virtual device drivers have increasingly integrated with container runtimes, such as Docker, where pluggable network drivers like the bridge or overlay types create virtualized networking stacks using virtual Ethernet (veth) pairs and user-space tunneling to enable isolated, high-performance communication between containers without physical NIC dependencies.[99] This integration supports scalable microservices deployments by providing lightweight virtualization of network interfaces, reducing latency in container-to-container traffic while maintaining security isolation.[100]Filter Drivers

Filter drivers are kernel-mode components that intercept, monitor, modify, or filter input/output (I/O) requests in the operating system's driver stack without directly managing hardware operations. They layer above physical device drivers to extend functionality, such as adding encryption to data streams or logging access patterns, enabling non-intrusive enhancements to existing device interactions. This architecture allows filter drivers to process requests transparently, passing unmodified operations through to lower layers when no intervention is needed.[101] In Windows, filter drivers are categorized as upper or lower filters within the I/O stack. Upper filters position themselves between applications or file systems and lower components to handle tasks like content scanning, while lower filters operate closer to the device for operations such as volume-level encryption. The Filter Manager (FltMgr.sys), a system-provided kernel-mode driver, coordinates minifilter drivers for file systems by managing callbacks, altitude assignments for ordering, and resource sharing to prevent conflicts. In Linux, the netfilter framework embeds hooks into the kernel's networking stack to enable packet manipulation, filtering, and transformation at various points like prerouting, input, and output.[102][103][104] Common examples include the BitLocker Drive Encryption filter driver (fvevol.sys), which intercepts volume I/O to enforce full-volume encryption transparently below the file system layer. Antivirus solutions employ file system minifilters to scan and block malicious file operations in real time, as demonstrated by Microsoft's AvScan sample implementation. Similarly, USB storage blockers utilize storage class filter drivers to deny read/write access to removable media, preventing unauthorized data transfer.[105][106][107] In the 2020s, filter drivers have experienced a notable rise in adoption for cybersecurity within cloud environments, where they facilitate secure data handling in distributed systems like cloud file synchronization. For instance, the Windows Cloud Files Mini Filter Driver supports OneDrive integration by filtering cloud-related I/O, highlighting their role in protecting hybrid workloads against emerging threats. This trend aligns with layered device driver models that enable modular stacking for scalable security extensions.[108][101]Identification and Management

Device Identifiers

Device identifiers are standardized strings or numerical values used by operating systems to uniquely recognize hardware components and associate them with appropriate device drivers. These identifiers are typically embedded in the device's firmware or configuration space and are read during system enumeration to ensure proper driver matching without manual intervention. Common standards include Hardware IDs for buses like USB and PCI, as well as ACPI identifiers for platform devices.[109] For USB devices, the primary identifiers are the Vendor ID (VID) and Product ID (PID), which are 16-bit values assigned by the USB Implementers Forum (USB-IF) to vendors and their specific products, respectively. The VID uniquely identifies the manufacturer, while the PID distinguishes individual device models within that vendor's lineup; for example, Intel's VID is 0x8086, and various PIDs are assigned to its products. This scheme enables plug-and-play functionality by allowing the operating system to query the device's descriptor during attachment.[110] In the PCI ecosystem, device identification relies on 16-bit Vendor IDs and Device IDs, managed by the PCI Special Interest Group (PCI-SIG) through its Code and ID Assignment Specification. Vendors register to receive unique Vendor IDs, and each device model gets a specific Device ID; these are stored in the PCI configuration space header and scanned by the host controller. Subsystem Vendor and Subsystem IDs provide additional granularity for OEM variations. ACPI identifiers, defined in the Advanced Configuration and Power Interface specification, use objects like _HID (Hardware ID) for primary identification and _CID (Compatible ID) list for alternatives. The _HID format is a four-character uppercase string followed by four hexadecimal digits (e.g., "PNP0A08" for PCI Express root bridges), ensuring compatibility across firmware implementations. These IDs are exposed in the ACPI namespace for operating systems to enumerate motherboard-integrated or platform-specific devices. Device identifiers are formatted as hierarchical strings in driver installation files, particularly in Windows INF files, to facilitate matching during installation. For USB, the format is "USB\VID_vvvv&PID_pppp" where vvvv and pppp are four-digit hexadecimal representations (e.g., "USB\VID_8086&PID_110B" for an Intel Bluetooth USB adapter). PCI formats follow "PCI\VEN_vvvv&DEV_dddd", with optional revisions or subsystems like "&REV_01". ACPI IDs appear as "ACPI\NNNN####", mirroring the _HID structure. These strings must be unique and are case-insensitive in INF parsing. USB host controllers, such as Intel's, use PCI formats like "PCI\VEN_8086&DEV_8C31" for the USB 3.0 eXtensible Host Controller.[109] Operating systems discover these identifiers through bus enumeration protocols implemented in the kernel. In Linux, the PCI subsystem scans the bus using configuration space reads, populating a device tree with Vendor and Device IDs; the lspci utility then queries this via sysfs (/sys/bus/pci/devices) to display enumerated devices, such as "00:1f.0 ISA bridge: Intel Corporation Device 06c0". Similar scanners exist for USB (lsusb) and ACPI (via /sys/firmware/acpi). This process occurs at boot or hotplug events to build the hardware inventory.[111][112] A key challenge in device identification is managing compatible IDs to support legacy hardware without compromising modern functionality. Compatible IDs, such as generic class codes (e.g., "USB\Class_09&SubClass_00" for full-speed hubs), serve as fallbacks when no exact hardware ID matches, enabling basic driver loading for older devices. However, reliance on them can result in limited features or suboptimal performance, as they prioritize broad compatibility over device-specific optimizations; developers must carefully order IDs in INF files to prefer exact matches first. Additionally, proliferating compatible IDs for legacy support increases the risk of incorrect driver assignments in diverse hardware ecosystems.[113][114]Driver Loading and Management

Device drivers are integrated into the operating system kernel to facilitate hardware interaction, with loading and management handled through standardized mechanisms that ensure compatibility and stability. These processes involve detecting hardware, matching drivers to devices, and dynamically incorporating modules without requiring system reboots where possible. Operating systems like Windows and Linux employ distinct but analogous approaches to automate or manually control this lifecycle, prioritizing seamless integration for diverse hardware configurations.[66] In Windows, dynamic loading primarily occurs via the Plug and Play (PnP) subsystem, which detects hardware insertions or changes and automatically enumerates devices to locate and install compatible drivers from the system's driver store. The PnP manager oversees this by querying device identifiers, selecting the highest-ranked driver package, and loading it into the kernel if it meets compatibility criteria, often without user intervention. For instance, connecting a USB device triggers enumeration, driver matching, and loading in a sequence that includes resource allocation and configuration. Manual loading supplements this through the Device Manager utility (accessible via devmgmt.msc), allowing administrators to browse devices, right-click for driver updates, or install packages from local sources or Windows Update.[115][116][117] Linux systems support dynamic loading through kernel mechanisms that respond to hardware events, but manual control is commonly exercised using the modprobe command, which intelligently loads kernel modules by resolving dependencies, passing parameters, and inserting them into the running kernel. For example, invokingmodprobe <module_name> automatically handles prerequisite modules and configures options from configuration files, enabling rapid deployment for newly detected hardware like network interfaces. Unloading and reloading are managed with commands such as rmmod to remove modules and modprobe to reinstate them, facilitating troubleshooting or updates without rebooting. Version control in Linux is aided by tools like DKMS (Dynamic Kernel Module Support), which automates recompilation of third-party modules against new kernel versions, ensuring persistence across updates by building and installing modules from source tarballs during kernel upgrades.[118][119]

Windows imposes signing requirements on drivers through Driver Signature Enforcement, introduced in Windows Vista and enforced by default in 64-bit editions since 2007, to verify authenticity and prevent malicious code execution during loading. This policy blocks unsigned or tampered drivers unless test mode is enabled or enforcement is temporarily disabled via boot options, with the driver store (managed by Windows Update) maintaining a repository of verified, versioned packages for automated distribution and rollback. In Linux, while signing is optional and distribution-dependent, tools like DKMS integrate with package managers to track module versions and facilitate selective reloading based on hardware needs.[120]