Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Finite-state machine

View on Wikipedia

A finite-state machine (FSM) or finite-state automaton (FSA, plural: automata), finite automaton, or simply a state machine, is a mathematical model of computation. It is an abstract machine that can be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any given time. The FSM can change from one state to another in response to some inputs; the change from one state to another is called a transition.[1] An FSM is defined by a list of its states, its initial state, and the inputs that trigger each transition. Finite-state machines are of two types—deterministic finite-state machines and non-deterministic finite-state machines.[2][better source needed] For any non-deterministic finite-state machine, an equivalent deterministic one can be constructed.[citation needed]

The behavior of state machines can be observed in many devices in modern society that perform a predetermined sequence of actions depending on a sequence of events with which they are presented. Simple examples are vending machines, which dispense products when the proper combination of coins is deposited; elevators, whose sequence of stops is determined by the floors requested by riders; traffic lights, which change sequence when cars are waiting; and combination locks, which require the input of a sequence of numbers in the proper order.

The finite-state machine has less computational power than some other models of computation such as the Turing machine.[3] The computational power distinction means there are computational tasks that a Turing machine can do but an FSM cannot. This is because an FSM's memory is limited by the number of states it has. A finite-state machine has the same computational power as a Turing machine that is restricted such that its head may only perform "read" operations, and always has to move from left to right. FSMs are studied in the more general field of automata theory.

Example: coin-operated turnstile

[edit]

An example of a simple mechanism that can be modeled by a state machine is a turnstile.[4][5] A turnstile, used to control access to subways and amusement park rides, is a gate with three rotating arms at waist height, one across the entryway. Initially the arms are locked, blocking the entry, preventing patrons from passing through. Depositing a coin or token in a slot on the turnstile unlocks the arms, allowing a single customer to push through. After the customer passes through, the arms are locked again until another coin is inserted.

Considered as a state machine, the turnstile has two possible states: Locked and Unlocked.[4] There are two possible inputs that affect its state: putting a coin in the slot (coin) and pushing the arm (push). In the locked state, pushing on the arm has no effect; no matter how many times the input push is given, it stays in the locked state. Putting a coin in – that is, giving the machine a coin input – shifts the state from Locked to Unlocked. In the unlocked state, putting additional coins in has no effect; that is, giving additional coin inputs does not change the state. A customer pushing through the arms gives a push input and resets the state to Locked.

The turnstile state machine can be represented by a state-transition table, showing for each possible state, the transitions between them (based upon the inputs given to the machine) and the outputs resulting from each input:

Current State Input Next State Output Locked coin Unlocked Unlocks the turnstile so that the customer can push through. push Locked None Unlocked coin Unlocked None push Locked When the customer has pushed through, locks the turnstile.

The turnstile state machine can also be represented by a directed graph called a state diagram (above). Each state is represented by a node (circle). Edges (arrows) show the transitions from one state to another. Each arrow is labeled with the input that triggers that transition. An input that doesn't cause a change of state (such as a coin input in the Unlocked state) is represented by a circular arrow returning to the original state. The arrow into the Locked node from the black dot indicates it is the initial state.

Concepts and terminology

[edit]A state is a description of the status of a system that is waiting to execute a transition. A transition is a set of actions to be executed when a condition is fulfilled or when an event is received. For example, when using an audio system to listen to the radio (the system is in the "radio" state), receiving a "next" stimulus results in moving to the next station. When the system is in the "CD" state, the "next" stimulus results in moving to the next track. Identical stimuli trigger different actions depending on the current state.

In some finite-state machine representations, it is also possible to associate actions with a state:

- an entry action: performed when entering the state, and

- an exit action: performed when exiting the state.

Representations

[edit]

State/Event table

[edit]Several state-transition table types are used. The most common representation is shown below: the combination of current state (e.g. B) and input (e.g. Y) shows the next state (e.g. C). By itself, the table cannot completely describe the action, so it is common to use footnotes. Other related representations may not have this limitation. For example, an FSM definition including the full action's information is possible using state tables (see also virtual finite-state machine).

Current state Input |

State A | State B | State C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input X | ... | ... | ... |

| Input Y | ... | State C | ... |

| Input Z | ... | ... | ... |

UML state machines

[edit]The Unified Modeling Language has a notation for describing state machines. UML state machines overcome the limitations[citation needed] of traditional finite-state machines while retaining their main benefits. UML state machines introduce the new concepts of hierarchically nested states and orthogonal regions, while extending the notion of actions. UML state machines have the characteristics of both Mealy machines and Moore machines. They support actions that depend on both the state of the system and the triggering event, as in Mealy machines, as well as entry and exit actions, which are associated with states rather than transitions, as in Moore machines.[citation needed]

SDL state machines

[edit]The Specification and Description Language is a standard from ITU that includes graphical symbols to describe actions in the transition:

- send an event

- receive an event

- start a timer

- cancel a timer

- start another concurrent state machine

- decision

SDL embeds basic data types called "Abstract Data Types", an action language, and an execution semantic in order to make the finite-state machine executable.[citation needed]

Other state diagrams

[edit]There are a large number of variants to represent an FSM such as the one in figure 3.

Usage

[edit]In addition to their use in modeling reactive systems presented here, finite-state machines are significant in many different areas, including electrical engineering, linguistics, computer science, philosophy, biology, mathematics, video game programming, and logic. Finite-state machines are a class of automata studied in automata theory and the theory of computation. In computer science, finite-state machines are widely used in modeling of application behavior (control theory), design of hardware digital systems, software engineering, compilers, network protocols, and computational linguistics.

Classification

[edit]Finite-state machines can be subdivided into acceptors, classifiers, transducers and sequencers.[6]

Acceptors

[edit]

Acceptors (also called detectors or recognizers) produce binary output, indicating whether or not the received input is accepted. Each state of an acceptor is either accepting or non accepting. Once all input has been received, if the current state is an accepting state, the input is accepted; otherwise it is rejected. As a rule, input is a sequence of symbols (characters); actions are not used. The start state can also be an accepting state, in which case the acceptor accepts the empty string. The example in figure 4 shows an acceptor that accepts the string "nice". In this acceptor, the only accepting state is state 7.

A (possibly infinite) set of symbol sequences, called a formal language, is a regular language if there is some acceptor that accepts exactly that set.[7] For example, the set of binary strings with an even number of zeroes is a regular language (cf. Fig. 5), while the set of all strings whose length is a prime number is not.[8]

An acceptor could also be described as defining a language that would contain every string accepted by the acceptor but none of the rejected ones; that language is accepted by the acceptor. By definition, the languages accepted by acceptors are the regular languages.

The problem of determining the language accepted by a given acceptor is an instance of the algebraic path problem—itself a generalization of the shortest path problem to graphs with edges weighted by the elements of an (arbitrary) semiring.[9][10][jargon]

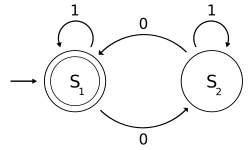

An example of an accepting state appears in Fig. 5: a deterministic finite automaton (DFA) that detects whether the binary input string contains an even number of 0s.

S1 (which is also the start state) indicates the state at which an even number of 0s has been input. S1 is therefore an accepting state. This acceptor will finish in an accept state, if the binary string contains an even number of 0s (including any binary string containing no 0s). Examples of strings accepted by this acceptor are ε (the empty string), 1, 11, 11..., 00, 010, 1010, 10110, etc.

Classifiers

[edit]Classifiers are a generalization of acceptors that produce n-ary output where n is strictly greater than two.[11]

Transducers

[edit]

Transducers produce output based on a given input and/or a state using actions. They are used for control applications and in the field of computational linguistics.

In control applications, two types are distinguished:

- Moore machine

- The FSM uses only entry actions, i.e., output depends only on state. The advantage of the Moore model is a simplification of the behaviour. Consider an elevator door. The state machine recognizes two commands: "command_open" and "command_close", which trigger state changes. The entry action (E:) in state "Opening" starts a motor opening the door, the entry action in state "Closing" starts a motor in the other direction closing the door. States "Opened" and "Closed" stop the motor when fully opened or closed. They signal to the outside world (e.g., to other state machines) the situation: "door is open" or "door is closed".

- Mealy machine

- The FSM also uses input actions, i.e., output depends on input and state. The use of a Mealy FSM leads often to a reduction of the number of states. The example in figure 7 shows a Mealy FSM implementing the same behaviour as in the Moore example (the behaviour depends on the implemented FSM execution model and will work, e.g., for virtual FSM but not for event-driven FSM). There are two input actions (I:): "start motor to close the door if command_close arrives" and "start motor in the other direction to open the door if command_open arrives". The "opening" and "closing" intermediate states are not shown.

Sequencers

[edit]Sequencers (also called generators) are a subclass of acceptors and transducers that have a single-letter input alphabet. They produce only one sequence, which can be seen as an output sequence of acceptor or transducer outputs.[6]

Determinism

[edit]A further distinction is between deterministic (DFA) and non-deterministic (NFA, GNFA) automata. In a deterministic automaton, every state has exactly one transition for each possible input. In a non-deterministic automaton, an input can lead to one, more than one, or no transition for a given state. The powerset construction algorithm can transform any nondeterministic automaton into a (usually more complex) deterministic automaton with identical functionality.

A finite-state machine with only one state is called a "combinatorial FSM". It only allows actions upon transition into a state. This concept is useful in cases where a number of finite-state machines are required to work together, and when it is convenient to consider a purely combinatorial part as a form of FSM to suit the design tools.[12]

Alternative semantics

[edit]There are other sets of semantics available to represent state machines. For example, there are tools for modeling and designing logic for embedded controllers.[13] They combine hierarchical state machines (which usually have more than one current state), flow graphs, and truth tables into one language, resulting in a different formalism and set of semantics.[14] These charts, like Harel's original state machines,[15] support hierarchically nested states, orthogonal regions, state actions, and transition actions.[16]

Mathematical model

[edit]In accordance with the general classification, the following formal definitions are found.

A deterministic finite-state machine or deterministic finite-state acceptor is a quintuple , where:

- is the input alphabet (a finite non-empty set of symbols);

- is a finite non-empty set of states;

- is an initial state, an element of ;

- is the state-transition function: (in a nondeterministic finite automaton it would be , i.e. would return a set of states);

- is the set of final states, a (possibly empty) subset of .

For both deterministic and non-deterministic FSMs, it is conventional to allow to be a partial function, i.e. does not have to be defined for every combination of and . If an FSM is in a state , the next symbol is and is not defined, then can announce an error (i.e. reject the input). This is useful in definitions of general state machines, but less useful when transforming the machine. Some algorithms in their default form may require total functions.

A finite-state machine has the same computational power as a Turing machine that is restricted such that its head may only perform "read" operations, and always has to move from left to right. That is, each formal language accepted by a finite-state machine is accepted by such a kind of restricted Turing machine, and vice versa.[17]

A finite-state transducer is a sextuple , where:

- is the input alphabet (a finite non-empty set of symbols);

- is the output alphabet (a finite non-empty set of symbols);

- is a finite non-empty set of states;

- is the initial state, an element of ;

- is the state-transition function: ;

- is the output function.

If the output function depends on the state and input symbol () that definition corresponds to the Mealy model, and can be modelled as a Mealy machine. If the output function depends only on the state () that definition corresponds to the Moore model, and can be modelled as a Moore machine. A finite-state machine with no output function at all is known as a semiautomaton or transition system.

If we disregard the first output symbol of a Moore machine, , then it can be readily converted to an output-equivalent Mealy machine by setting the output function of every Mealy transition (i.e. labeling every edge) with the output symbol given of the destination Moore state. The converse transformation is less straightforward because a Mealy machine state may have different output labels on its incoming transitions (edges). Every such state needs to be split in multiple Moore machine states, one for every incident output symbol.[18]

Optimization

[edit]Optimizing an FSM means finding a machine with the minimum number of states that performs the same function. The fastest known algorithm doing this is the Hopcroft minimization algorithm.[19][20] Other techniques include using an implication table, or the Moore reduction procedure.[21] Additionally, acyclic FSAs can be minimized in linear time.[22]

Implementation

[edit]Hardware applications

[edit]

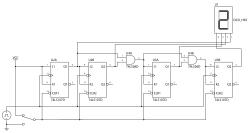

In a digital circuit, an FSM may be built using a programmable logic device, a programmable logic controller, logic gates and flip flops or relays. More specifically, a hardware implementation requires a register to store state variables, a block of combinational logic that determines the state transition, and a second block of combinational logic that determines the output of an FSM.

In a Medvedev machine, the output is directly connected to the state flip-flops minimizing the time delay between flip-flops and output.[23][24]

Through state encoding for low power state machines may be optimized to minimize power consumption.

Software applications

[edit]The following concepts are commonly used to build software applications with finite-state machines:

- Automata-based programming

- Event-driven finite-state machine

- Virtual finite-state machine

- State design pattern

Finite-state machines and compilers

[edit]Finite automata are often used in the frontend of programming language compilers. Such a frontend may comprise several finite-state machines that implement a lexical analyzer and a parser. Starting from a sequence of characters, the lexical analyzer builds a sequence of language tokens (such as reserved words, literals, and identifiers) from which the parser builds a syntax tree. The lexical analyzer and the parser handle the regular and context-free parts of the programming language's grammar.[25]

See also

[edit]- Abstract state machines

- Alternating finite automaton

- Communicating finite-state machine

- Control system

- Control table

- Decision tables

- DEVS

- Hidden Markov model

- Petri net

- Pushdown automaton

- Quantum finite automaton

- SCXML

- Semiautomaton

- Semigroup action

- Sequential logic

- State diagram

- Synchronizing word

- Transformation semigroup

- Transition system

- Tree automaton

- Turing machine

- UML state machine

References

[edit]- ^ Wang, Jiacun (2019). Formal Methods in Computer Science. CRC Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4987-7532-8.

- ^ "Finite State Machines – Brilliant Math & Science Wiki". brilliant.org. Retrieved 2018-04-14.

- ^ Belzer, Jack; Holzman, Albert George; Kent, Allen (1975). Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Technology. Vol. 25. USA: CRC Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8247-2275-3.

- ^ a b Koshy, Thomas (2004). Discrete Mathematics With Applications. Academic Press. p. 762. ISBN 978-0-12-421180-3.

- ^ Wright, David R. (2005). "Finite State Machines" (PDF). CSC215 Class Notes. David R. Wright website, N. Carolina State Univ. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-27. Retrieved 2012-07-14.

- ^ a b Keller, Robert M. (2001). "Classifiers, Acceptors, Transducers, and Sequencers" (PDF). Computer Science: Abstraction to Implementation (PDF). Harvey Mudd College. p. 480.

- ^ Hopcroft & Ullman 1979, pp. 18.

- ^ Hopcroft, Motwani & Ullman 2006, pp. 130–1.

- ^ Pouly, Marc; Kohlas, Jürg (2011). Generic Inference: A Unifying Theory for Automated Reasoning. John Wiley & Sons. Chapter 6. Valuation Algebras for Path Problems, p. 223 in particular. ISBN 978-1-118-01086-0.

- ^ Jacek Jonczy (Jun 2008). "Algebraic path problems" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-21. Retrieved 2014-08-20., p. 34

- ^ Felkin, M. (2007). Guillet, Fabrice; Hamilton, Howard J. (eds.). Quality Measures in Data Mining - Studies in Computational Intelligence. Vol. 43. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 277–278. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-44918-8_12. ISBN 978-3-540-44911-9.

- ^ Brutscheck, M., Berger, S., Franke, M., Schwarzbacher, A., Becker, S.: Structural Division Procedure for Efficient IC Analysis. IET Irish Signals and Systems Conference, (ISSC 2008), pp.18–23. Galway, Ireland, 18–19 June 2008. [1]

- ^ "Tiwari, A. (2002). Formal Semantics and Analysis Methods for Simulink Stateflow Models" (PDF). sri.com. Retrieved 2018-04-14.

- ^ Hamon, G. (2005). A Denotational Semantics for Stateflow. International Conference on Embedded Software. Jersey City, NJ: ACM. pp. 164–172. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.89.8817.

- ^ "Harel, D. (1987). A Visual Formalism for Complex Systems. Science of Computer Programming, 231–274" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ "Alur, R., Kanade, A., Ramesh, S., & Shashidhar, K. C. (2008). Symbolic analysis for improving simulation coverage of Simulink/Stateflow models. International Conference on Embedded Software (pp. 89–98). Atlanta, GA: ACM" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-15.

- ^ Black, Paul E (12 May 2008). "Finite State Machine". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures. U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ Anderson, James Andrew; Head, Thomas J. (2006). Automata theory with modern applications. Cambridge University Press. pp. 105–108. ISBN 978-0-521-84887-9.

- ^ Hopcroft, John (1971), "An n log n algorithm for minimizing states in a finite automaton", Theory of Machines and Computations, Elsevier, pp. 189–196, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-417750-5.50022-1, ISBN 978-0-12-417750-5, retrieved 2025-09-18

- ^ Almeida, Marco; Moreira, Nelma; Reis, Rogerio (2007). On the performance of automata minimization algorithms (PDF) (Technical Report). Vol. DCC-2007-03. Porto Univ. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- ^ Edward F. Moore (1956). C.E. Shannon and J. McCarthy (ed.). "Gedanken-Experiments on Sequential Machines". Annals of Mathematics Studies. 34. Princeton University Press: 129–153. Here: Theorem 4, p.142.

- ^ Revuz, D. (1992). "Minimization of Acyclic automata in Linear Time". Theoretical Computer Science. 92: 181–189. doi:10.1016/0304-3975(92)90142-3.

- ^ Kaeslin, Hubert (2008). "Mealy, Moore, Medvedev-type and combinatorial output bits". Digital Integrated Circuit Design: From VLSI Architectures to CMOS Fabrication. Cambridge University Press. p. 787. ISBN 978-0-521-88267-5.

- ^ Slides Archived 18 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Synchronous Finite State Machines; Design and Behaviour, University of Applied Sciences Hamburg, p.18

- ^ Aho, Alfred V.; Sethi, Ravi; Ullman, Jeffrey D. (1986). Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools (1st ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-10088-4.

Sources

[edit]- Hopcroft, John E.; Ullman, Jeffrey D. (1979). Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation (1st ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-02988-X. (accessible to patrons with print disabilities)

- Hopcroft, John E.; Motwani, Rajeev; Ullman, Jeffrey D. (2006) [1979]. Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-321-45536-3.

Further reading

[edit]General

[edit]- Sakarovitch, Jacques (2009). Elements of automata theory. Translated from the French by Reuben Thomas. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84425-3. Zbl 1188.68177.

- Wagner, F., "Modeling Software with Finite State Machines: A Practical Approach", Auerbach Publications, 2006, ISBN 0-8493-8086-3.

- ITU-T, Recommendation Z.100 Specification and Description Language (SDL)

- Samek, M., Practical Statecharts in C/C++, CMP Books, 2002, ISBN 1-57820-110-1.

- Samek, M., Practical UML Statecharts in C/C++, 2nd Edition, Newnes, 2008, ISBN 0-7506-8706-1.

- Gardner, T., Advanced State Management Archived 2008-11-19 at the Wayback Machine, 2007

- Cassandras, C., Lafortune, S., "Introduction to Discrete Event Systems". Kluwer, 1999, ISBN 0-7923-8609-4.

- Timothy Kam, Synthesis of Finite State Machines: Functional Optimization. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston 1997, ISBN 0-7923-9842-4

- Tiziano Villa, Synthesis of Finite State Machines: Logic Optimization. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston 1997, ISBN 0-7923-9892-0

- Carroll, J., Long, D., Theory of Finite Automata with an Introduction to Formal Languages. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 1989.

- Kohavi, Z., Switching and Finite Automata Theory. McGraw-Hill, 1978.

- Gill, A., Introduction to the Theory of Finite-state Machines. McGraw-Hill, 1962.

- Ginsburg, S., An Introduction to Mathematical Machine Theory. Addison-Wesley, 1962.

Finite-state machines (automata theory) in theoretical computer science

[edit]- Arbib, Michael A. (1969). Theories of Abstract Automata (1st ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc. ISBN 978-0-13-913368-8.

- Bobrow, Leonard S.; Arbib, Michael A. (1974). Discrete Mathematics: Applied Algebra for Computer and Information Science (1st ed.). Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7216-1768-8.

- Booth, Taylor L. (1967). Sequential Machines and Automata Theory (1st ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number 67-25924.

- Boolos, George; Jeffrey, Richard (1999) [1989]. Computability and Logic (3rd ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20402-6.

- Brookshear, J. Glenn (1989). Theory of Computation: Formal Languages, Automata, and Complexity. Redwood City, California: Benjamin/Cummings Publish Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-8053-0143-4.

- Davis, Martin; Sigal, Ron; Weyuker, Elaine J. (1994). Computability, Complexity, and Languages and Logic: Fundamentals of Theoretical Computer Science (2nd ed.). San Diego: Academic Press, Harcourt, Brace & Company. ISBN 978-0-12-206382-4.

- Hopkin, David; Moss, Barbara (1976). Automata. New York: Elsevier North-Holland. ISBN 978-0-444-00249-5.

- Kozen, Dexter C. (1997). Automata and Computability (1st ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-94907-9.

- Lewis, Harry R.; Papadimitriou, Christos H. (1998). Elements of the Theory of Computation (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-262478-7.

- Linz, Peter (2006). Formal Languages and Automata (4th ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett. ISBN 978-0-7637-3798-6.

- Minsky, Marvin (1967). Computation: Finite and Infinite Machines (1st ed.). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Papadimitriou, Christos (1993). Computational Complexity (1st ed.). Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-53082-7.

- Pippenger, Nicholas (1997). Theories of Computability (1st ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55380-3.

- Rodger, Susan; Finley, Thomas (2006). JFLAP: An Interactive Formal Languages and Automata Package (1st ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett. ISBN 978-0-7637-3834-1.

- Sipser, Michael (2006). Introduction to the Theory of Computation (2nd ed.). Boston Mass: Thomson Course Technology. ISBN 978-0-534-95097-2.

- Wood, Derick (1987). Theory of Computation (1st ed.). New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-06-047208-5.

Abstract state machines in theoretical computer science

[edit]- Gurevich, Yuri (July 2000). "Sequential Abstract State Machines Capture Sequential Algorithms" (PDF). ACM Transactions on Computational Logic. 1 (1): 77–111. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.146.3017. doi:10.1145/343369.343384. S2CID 2031696.

Machine learning using finite-state algorithms

[edit]- Mitchell, Tom M. (1997). Machine Learning (1st ed.). New York: WCB/McGraw-Hill Corporation. ISBN 978-0-07-042807-2.

Hardware engineering: state minimization and synthesis of sequential circuits

[edit]- Booth, Taylor L. (1967). Sequential Machines and Automata Theory (1st ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number 67-25924.

- Booth, Taylor L. (1971). Digital Networks and Computer Systems (1st ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-08840-0.

- McCluskey, E. J. (1965). Introduction to the Theory of Switching Circuits (1st ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number 65-17394.

- Hill, Fredrick J.; Peterson, Gerald R. (1965). Introduction to the Theory of Switching Circuits (1st ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number 65-17394.

Finite Markov chain processes

[edit]- "We may think of a Markov chain as a process that moves successively through a set of states s1, s2, …, sr. … if it is in state si it moves on to the next stop to state sj with probability pij. These probabilities can be exhibited in the form of a transition matrix" (Kemeny (1959), p. 384)

Finite Markov-chain processes are also known as subshifts of finite type.

- Booth, Taylor L. (1967). Sequential Machines and Automata Theory (1st ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number 67-25924.

- Kemeny, John G.; Mirkil, Hazleton; Snell, J. Laurie; Thompson, Gerald L. (1959). Finite Mathematical Structures (1st ed.). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc. Library of Congress Card Catalog Number 59-12841. Chapter 6 "Finite Markov Chains".

External links

[edit]- statecharts.online Comprehensive and interactive tutorial on statecharts and state machines

- Modeling a Simple AI behavior using a Finite State Machine Example of usage in Video Games

- Free On-Line Dictionary of Computing description of Finite-State Machines

- NIST Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures description of Finite-State Machines

- A brief overview of state machine types, comparing theoretical aspects of Mealy, Moore, Harel & UML state machines.

Finite-state machine

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Motivation

A finite-state machine is an abstract computational model that represents systems capable of exhibiting sequential behavior through a limited set of conditions known as states. At any given moment, the machine resides in exactly one state, which encapsulates the relevant history of prior inputs, and transitions to another state based on the current input. This structure allows the machine to produce outputs dependent on both the current state and input, providing a framework for modeling processes with finite memory where the system's response to future inputs is determined solely by its present condition rather than an unlimited record of the past.[6] The concept traces back to Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts' 1943 model of neural activity, with significant formalization in the 1950s as part of early efforts in automata theory to model digital circuits and recognize patterns in sequences, such as those encountered in language processing.[7][6] Early foundations were laid by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts in 1943, who modeled neural activity using finite automata in their paper "A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity," laying foundational work for cybernetics and automata theory.[3] Stephen Kleene's 1956 work formalized finite automata, building on McCulloch and Pitts' models, and introduced regular expressions as a means to represent events in nerve nets, linking them to the computational capabilities of simple neural models and laying the groundwork for understanding sequential logic in hardware design. Building on this, Michael Rabin and Dana Scott's 1959 paper formalized finite automata for classifying input tapes and solving decision problems, emphasizing their role in theoretical computer science and circuit synthesis.[8][7][6] Key developments in automata theory during the 1950s and 1960s further solidified the finite-state machine's foundations, particularly through its connection to regular languages—the class of patterns recognizable by such machines. Kleene's introduction of regular expressions in his 1956 paper provided an algebraic notation for describing these languages, enabling precise specifications of state transitions and influencing compiler design and text processing. This era's advancements highlighted the model's utility in abstracting real-world systems like communication protocols and control devices, where exhaustive memory is neither necessary nor feasible.[8] The emphasis on finiteness stems from the model's inherent limitation to a fixed number of states, which bounds the memory and computational power compared to universal models like the Turing machine. Unlike Turing machines, which simulate arbitrary computation via an infinite tape for unbounded storage, finite-state machines are constrained to recognize only regular languages and cannot handle computations requiring indefinite memory, such as those involving nested structures or recursion. This restriction makes them ideal for efficient, predictable implementations in resource-limited environments like embedded systems.[3]Turnstile Example

A coin-operated turnstile provides a classic illustration of a finite-state machine in operation, modeling access control in environments such as subways or amusement parks. The turnstile begins in a locked state, preventing passage until a valid input is received. Inserting a coin unlocks the mechanism, allowing a user to push through and advance to the next position, after which it relocks to require another payment for subsequent entries. This setup demonstrates how the machine's behavior depends on its current state and incoming events, ensuring controlled and predictable responses.[9][10] The turnstile FSM features two primary states: locked, where entry is barred, and unlocked, where passage is permitted. The inputs consist of two events: coin, representing payment insertion, and push, simulating the physical force to rotate the arms. Outputs are implicit and state-dependent; in the locked state, no passage occurs, while in the unlocked state, the turnstile rotates to allow one person through, effectively granting access. These elements capture the machine's reactive nature without explicit signaling beyond mechanical feedback.[9][11] The transitions define how inputs alter states, with invalid inputs typically resulting in no change to maintain security. A coin input in the locked state triggers a transition to unlocked, enabling entry. Conversely, a push input in the unlocked state returns it to locked after allowing passage. If a push occurs in the locked state, the machine remains locked, ignoring the attempt. A coin input in the unlocked state also leaves it unchanged, as payment is unnecessary post-unlock. These rules ensure the FSM only advances on valid sequences, rejecting unauthorized actions.[9][10] To handle error conditions, such as repeated invalid pushes or forced entry attempts, the model can be extended with a jammed or violation state for fault tolerance. In this augmented FSM, abnormal events like pushing a locked turnstile or excessive force trigger a transition to the violation state, where an alarm activates and the mechanism halts. Recovery occurs via a reset event, returning to the locked state and deactivating the alarm, thus incorporating error handling without disrupting the core logic.[11] The following table summarizes the transitions for the basic turnstile FSM:| Current State | Input | Next State | Action/Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Locked | Coin | Unlocked | Unlock turnstile |

| Locked | Push | Locked | No action (ignore) |

| Unlocked | Push | Locked | Allow passage, relock |

| Unlocked | Coin | Unlocked | No action (ignore) |

Fundamental Concepts

States, Inputs, and Outputs

A finite-state machine (FSM) consists of a finite set of states, denoted as , which represent the distinct conditions or modes in which the machine can exist at any given time. Exactly one state is active at any moment, capturing the system's configuration or "memory" of past inputs.[12] Among these, there is a designated initial state , from which the machine begins operation upon receiving its first input.[13] For FSMs functioning as acceptors or recognizers, a subset identifies the accepting states, where the machine halts after processing an input string if it determines the input is valid according to the defined language.[13] The inputs to an FSM are drawn from a finite input alphabet , a set of symbols or events that can trigger changes in the machine's behavior. These inputs serve as the stimuli processed sequentially, with each symbol representing a discrete event or signal that the machine responds to.[12] The term "event" is often used more broadly to encompass any input that causes a state change, including external signals in reactive systems.[14] Synonymous terminology includes "symbols" for individual elements of and "conditions" interchangeably with states in descriptive contexts.[12] Outputs are relevant primarily in transducer models of FSMs, where the machine not only changes states but also produces responses from an output alphabet . In the Mealy model, outputs are generated as a total function , depending on both the current state and the input, allowing immediate reaction during transitions.[15] This approach, introduced by George H. Mealy, enables outputs to vary dynamically with incoming stimuli.[16] Conversely, in the Moore model, outputs are determined solely by the current state via a total function , producing consistent responses for each state regardless of the triggering input.[17] This model, proposed by Edward F. Moore, simplifies output logic by associating it directly with states. Some FSM designs distinguish active states, where outputs or actions occur, from idle states, in which the machine awaits input without generating responses.[18] For illustration, consider a turnstile FSM with states "locked" and "unlocked," where coin inputs from drive transitions, and outputs indicate access granted or denied.[13]Transitions and Events

In finite-state machines (FSMs), transitions define the dynamic behavior by specifying how the machine moves from one state to another in response to inputs. A transition is a mapping that, given the current state and an input, determines the next state and may also produce an output.[18] This mechanism ensures that the FSM evolves predictably based on its configuration, with transitions often triggered synchronously at clock edges in hardware implementations.[18] In event-driven or reactive systems, transitions are initiated by events, which serve as the inputs prompting state changes. Events can include signals, user actions, or environmental stimuli, and the FSM responds by firing a valid transition if the event is applicable to the current state; otherwise, the event is typically ignored to maintain stability.[19] For instance, in a turnstile system, a "coin" event in the locked state triggers a transition to the unlocked state, while a "push" event in the same state is ignored, preventing unauthorized passage without altering the state.[11] Nondeterminism introduces the possibility of multiple transitions from the same state for a given input, allowing the FSM to branch to several potential next states, which models uncertainty or parallelism in computation.[20] This contrasts with deterministic FSMs, where each input uniquely determines the next state, and is explored further in classifications of FSM types. Sequences of transitions form paths through the state space, enabling complex behaviors such as cycles, where the machine loops back to a previous state to repeat actions. In the turnstile example, a cycle emerges from the unlocked state via a "push" event back to locked, allowing repeated use after payment and modeling ongoing operation.[11] These paths capture the FSM's response to input sequences, ensuring consistent handling of repetitive or iterative scenarios.[18] Dead states act as sinks in the FSM, representing error conditions where no further valid transitions are possible, trapping the machine indefinitely regardless of subsequent inputs. They are commonly used for error handling, such as in protocol implementations where invalid sequences lead to a fault state requiring external reset.[21] In design, dead states help isolate failures without disrupting the overall model.[18]Mathematical Model

Formal Components

A finite-state machine, in its basic form as an acceptor or recognizer, is formally defined as a quintuple , where is a finite set of states, is a finite input alphabet, is the transition function that maps a current state and an input symbol to a next state, is the initial state, and is the set of accepting states.[22][23] This structure assumes that both and are finite, ensuring the machine's computational resources remain bounded, and that is a total function, defined for every pair in .[22] For machines that produce outputs, known as finite-state transducers, the basic tuple is extended with a finite output alphabet and an output function .[24] In a Moore machine, outputs depend solely on the current state, with ; the full tuple is thus , where accepting states may be omitted if the machine is not used as an acceptor.[24] This model ensures that the output is determined immediately upon entering a state, independent of the triggering input.[24] In contrast, a Mealy machine associates outputs with transitions, so ; the tuple becomes , or equivalently, the transition function can incorporate outputs as .[24] Here, the output is produced based on both the current state and the input symbol, allowing for more immediate response to inputs but potentially leading to different output timing compared to Moore machines.[24] As with the basic FSM, finiteness of , , and is required, and functions are total for completeness.[24]Transition Function and Semantics

The transition function, denoted as , is a central component of a finite-state machine (FSM) that specifies how the machine changes states in response to inputs. For a deterministic FSM (DFA), is a total function , mapping each pair of a current state and an input symbol to a unique next state in .[25] In a nondeterministic FSM (NFA), is a partial function , where is the power set of , allowing the machine to transition to a set of possible next states (or none, if partial).[26] The operational semantics of an FSM are defined by its computation or run on an input string , starting from the initial state . The run proceeds iteratively: the state after the first symbol is , then , and so on, yielding a final state after processing all symbols.[25] For a DFA, the run produces a unique sequence of states; for an NFA, it may produce a set of possible state sequences, with acceptance if at least one path reaches a state in the accepting set . The machine accepts if .[27] To handle outputs, FSMs are classified into Moore and Mealy types, which differ in how outputs are generated during a run. In a Moore machine, outputs are associated solely with states, producing an output sequence where each output depends only on the current state (e.g., output at step is a function of ).[28] In a Mealy machine, outputs are associated with state-input pairs, so the output at each step depends on both the current state and the input symbol (e.g., output for is a function of and ).[29] The language recognized by an FSM , denoted , consists of all strings that lead to an accepting state under the extended transition function (or to for DFAs), defined recursively as and , with if .[25] Kleene's theorem establishes the equivalence between the languages recognized by FSMs and those described by regular expressions, showing that FSMs capture exactly the regular languages.[30]Representations

State Diagrams and Visual Notations

State diagrams provide a graphical representation of finite-state machines (FSMs), visually depicting the mathematical model where states are shown as nodes, typically circles or rounded rectangles, and transitions between states are illustrated as directed edges or arrows.[31] These edges are labeled with inputs that trigger the transition, and in output-producing FSMs, such as Mealy machines, the labels may also include corresponding outputs, for example, "coin/unlock" to denote an input event and its resulting action.[31] This notation allows designers to intuitively map the sequence of states and events, grounding the abstract components of states, transitions, and the transition function in a comprehensible visual form.[32] In object-oriented modeling, UML state machines extend traditional state diagrams with advanced features to handle more complex behaviors. States in UML are represented as rounded rectangles, which can contain nested substates for hierarchy, and transitions are arrows annotated with event triggers, guard conditions (Boolean expressions like [x > 0]), and actions (e.g., /setFlag). Entry and exit actions are specified within state compartments, executed automatically upon entering or leaving a state, while history states—denoted by a circle with an "H" for shallow history or "H*" for deep history—allow the machine to resume from the most recent active substate configuration after interruption. These extensions make UML state machines suitable for modeling reactive systems in software design.[33] SDL (Specification and Description Language) state machines, standardized by ITU-T for telecommunications systems, employ a graphical notation where states are depicted as rectangular boxes within process diagrams, and transitions are flow lines triggered by input signals or spontaneous events. Channels, represented as lines connecting blocks or processes, define communication paths with unidirectional or bidirectional signal routes, while signals—discrete events with optional parameters—are the primary inputs that consume from input queues to fire transitions. This structure supports concurrent, distributed systems by modeling agents (e.g., processes) as extended FSMs with explicit interfaces via gates and channels.[34][35] Other visual notations related to FSMs include Harel statecharts, which extend state diagrams with hierarchy and orthogonality to manage complexity in reactive systems; states can nest substates, and orthogonal regions allow parallel independent state machines within a superstate, with transitions broadcast across components. Petri nets, while distinct, model concurrency using places (circles), transitions (bars), and tokens, offering a graph-based alternative to FSMs for systems with multiple simultaneous states but differing in their emphasis on resource allocation rather than strict sequential transitions.[36][37] The primary advantages of state diagrams and their variants lie in their intuitiveness for design and debugging: they facilitate visual inspection of state sequences and transitions, enabling early detection of inconsistencies like conflicting inputs or unreachable states, which simplifies verification in complex FSMs compared to purely textual or tabular forms.[38]Tabular Representations

Tabular representations provide a structured, non-graphical method to specify finite-state machines (FSMs) by enumerating all possible state transitions in a matrix format, facilitating precise implementation and verification. Unlike visual diagrams, these tables offer an exhaustive listing of behaviors, making them suitable for automated processing and formal analysis.[39] The state-transition table is the primary tabular form, with rows representing the current states of the FSM and columns corresponding to possible inputs. Each cell in the table specifies the next state and, for output-producing FSMs, the associated output produced upon transition. This format encodes the FSM's transition function directly, allowing for straightforward translation into code or hardware logic, such as ROM-based implementations where the table serves as a lookup mechanism.[39] For deterministic FSMs, each input-state pair yields a unique next state, ensuring the table is complete without ambiguity.[40] A variant known as the state/event table emphasizes events—discrete occurrences that trigger transitions—over continuous inputs, which is particularly useful in reactive systems where behaviors respond to asynchronous signals like user actions or sensor triggers. In this representation, columns are labeled with events rather than inputs, and cells indicate the next state or no change (often denoted by a dash or self-reference), along with any actions. This approach highlights event-driven dynamics, making it easier to model systems with sporadic inputs, such as control software.[40][41] Tabular representations offer several advantages, including exhaustiveness that ensures all transitions are explicitly defined, reducing the risk of overlooked behaviors compared to graphical notations. They are compact for FSMs with few states and inputs, enabling easy automation in tools for simulation, verification, and code generation, and they support efficient hardware realization through direct mapping to combinational logic.[39][41] Additionally, tables clarify ignored events by including entries for non-effecting cases, promoting clarity in design.[40] Consider the classic turnstile example, a coin-operated gate with two states: Locked and Unlocked. Inputs are coin insertion and push attempts, with outputs controlling the lock mechanism. The state-transition table for this Mealy machine is as follows:| Current State | Input | Next State | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Locked | coin | Unlocked | unlock |

| Locked | push | Locked | none |

| Unlocked | coin | Unlocked | none |

| Unlocked | push | Locked | lock |