Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sushi

View on Wikipedia

Mixed sushi platter | |

| Place of origin | Japan |

|---|---|

| Region or state | East Asia |

| Main ingredients |

|

Sushi (すし, 寿司, 鮨, 鮓; pronounced [sɯɕiꜜ] or [sɯꜜɕi] ⓘ) is a traditional Japanese dish made with vinegared rice (鮨飯, sushi-meshi), typically seasoned with sugar and salt, and combined with a variety of ingredients (ねた, neta), such as seafood, vegetables, or meat; raw seafood is the most common, although some may be cooked. While sushi has numerous styles and presentations, the current defining component is the vinegared rice, also known as shari (しゃり), or sumeshi (酢飯).[1]

The modern form of sushi is believed to have been created by Hanaya Yohei, who invented nigiri-zushi, the most commonly recognized type today, in which seafood is placed on hand-pressed, vinegared rice. This innovation occurred around 1824 in the Edo period (1603–1867). It was the fast food of the chōnin class in the Edo period.[2][3][4]

Sushi is traditionally made with medium-grain white rice, although it can also be prepared with brown rice or short-grain rice. It is commonly prepared with seafood, such as squid, eel, yellowtail, salmon, tuna, or imitation crab meat (surimi). Certain types of sushi are vegetarian. It is often served with pickled ginger (gari), wasabi, and soy sauce. Daikon radish or pickled daikon (takuan) are popular garnishes for the dish.

Sushi is sometimes confused with sashimi, a dish that consists of thinly sliced raw fish or occasionally meat, without sushi rice.[5]

History

[edit]Narezushi

[edit]

A dish known as narezushi (馴れ寿司, 熟寿司), "matured fish", stored in fermented rice for possibly months at a time, has been cited as one of the early influences for the Japanese practice of applying rice on raw fish. The fish was fermented with rice vinegar, salt, and rice, after which the rice was discarded.[6] Narezushi is also called honnare, meaning "fully fermented", as opposed to namanare, meaning "partially fermented", a type of sushi that appeared in the Muromachi period.[7]

Fermented fish using rice, such as narezushi, originated in Southeast Asia, where it was made to preserve freshwater fish, possibly in the Mekong River basin, which is now Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam, and in the Irrawaddy River basin, which is now Myanmar.[7] The first mention of a narezushi-like food is in a Chinese dictionary thought to be from the fourth century, in this instance referring to salted fish that had been placed in cooked or steamed rice, which caused it to undergo a fermentation process via lactic acid.[8][9] Fermentation methods following similar logic in other Asian rice cultures include burong isda, balao-balao, and tinapayan of the Philippines; pekasam of Indonesia and Malaysia; padaek (ປາແດກ) of Laos; pla ra (ปลาร้า) of Thailand; sikhae (식해) of Korea; and Mắm bò hóc or cá chua of Vietnam.[9][6][10][11][12][excessive citations]

The lacto-fermentation of the rice prevents the fish from spoiling. When wet-field rice cultivation was introduced during the Yayoi period, lakes and rivers would flood during the rainy season and fish would get caught in the rice paddy fields. Pickling was a way to preserve the excess fish and guarantee food for the following months, and narezushi became an important source of protein for Japanese consumers. The term sushi literally means "sour-tasting", as the overall dish has a sour and umami or savory taste. The term comes from an antiquated し shi terminal-form conjugation, no longer used in other contexts, of the adjectival verb sui (酸い, "to be sour"),[13] resulting in the term sushi (酸し).[14] Narezushi still exists as a regional specialty, notably as funa-zushi from Shiga Prefecture.[15]

In the Yōrō Code (養老律令, Yōrō-ritsuryō) of 718, the characters for "鮨" and "鮓" are written as a tribute to the Japanese imperial court, and although there are various theories as to what exactly this food was, it is possible that it referred to narezushi.[16]

Namanare

[edit]Until the early 19th century, sushi slowly changed with Japanese cuisine. The Japanese started eating three meals a day, rice was boiled instead of steamed, and of large importance was the development of rice vinegar.[17]

During the Muromachi period (1336–1573), the Japanese invented a style of sushi called namanare or namanari (生成、なまなれ、なまなり), which means "partially fermented". The fermentation period of namanare was shorter than that of the earlier narezushi, and the rice used for fermentation was also eaten with the fish. In other words, with the invention of namanare, sushi changed from a preserved fish food to a food where fish and rice are eaten together. After the appearance of namanare, sake and sake lees were used to shorten fermentation, and vinegar was used in the Edo period.[7]

Hayazushi

[edit]

During the Edo period (1603–1867), a third type of sushi, haya-zushi (早寿司、早ずし, "fast sushi"), was developed. Haya-zushi differed from earlier sushi in that instead of lactic fermentation of rice, vinegar, a fermented food, was mixed with rice to give it a sour taste so that it could be eaten at the same time as the fish. Previously, sushi had evolved with a focus on shortening the fermentation period, but with the invention of haya-zushi, which is simply mixed with vinegar, the fermentation process was eliminated and sushi became a fast food. Many types of sushi known in the world today, such as chirashizushi (散らし寿司, "scattered sushi"), inarizushi (稲荷寿司, "Inari sushi"), makizushi (巻寿司, "rolled sushi"), and nigirizushi (握り寿司, "hand-pressed sushi"), were invented during this period, and they are a type of haya-zushi. Each region utilizes local flavors to produce a variety of sushi that has been passed down for many generations. A 1689 cookbook describes haya-zushi, and a 1728 cookbook describes pouring vinegar over hako-zushi (箱ずし, "box sushi") (square sushi made by filling a wooden frame with rice).[7]

Today's style of nigirizushi (握り寿司, "hand-pressed sushi"), consisting of an oblong mound of rice with a slice of fish draped over it, became popular in Edo (contemporary Tokyo) in the 1820s or 1830s. One common story of the origin of nigirizushi is of the chef Hanaya Yohei (1799–1858), who invented or perfected the technique in 1824 at his shop in Ryōgoku.[15] The nigirizushi of this period was somewhat different from modern nigirizushi. The sushi rice of this period was about three times the size of today's nigirizushi. The amount of vinegar used was half that of today's sushi, and the type of vinegar developed during this period, called aka-su (赤酢, "red vinegar"), was made by fermenting sake lees. They also used slightly more salt than in modern times instead of sugar. Seafood served over rice was prepared in a variety of ways. This red vinegar was developed by Nakano Matazaemon (中野 又佐衛門), who is the founder of Mizkan, a company that still develops and sells vinegar and other seasonings today.[7]

The dish was originally termed Edomae zushi as it used freshly caught fish from the Edo-mae (Edo or Tokyo Bay); the term Edomae nigirizushi is still used today as a by-word for quality sushi, regardless of its ingredients' origins.[18][19]

Conveyor belt sushi

[edit]

In 1958, Yoshiaki Shiraishi opened the first conveyor belt sushi restaurant (回転寿司, kaiten-zushi) named "Genroku Zushi" in Higashi-Osaka. In conveyor belt sushi restaurants, conveyor belts installed along tables and counters in the restaurant transport plates of sushi to customers. Generally, the bill is based on the number of plates, with different colored plates representing the price of the sushi.[20][21][22]

When Genroku Sushi opened a restaurant at the Japan World Exposition, Osaka, 1970, it won an award at the expo, and conveyor belt sushi restaurants became known throughout Japan. In 1973, an automatic tea dispenser was developed, which is now used in conveyor belt sushi restaurants today. When the patent for conveyor belt sushi restaurants expired, a chain of conveyor belt sushi restaurants was established, spreading conveyor belt sushi throughout Japan and further popularizing and lowering the price of sushi. By 2021, the conveyor belt sushi market had grown to 700 billion yen and spread outside Japan.[20][21][22]

Sushi in English

[edit]The earliest written mention of sushi in English described in the Oxford English Dictionary is in an 1893 book, A Japanese Interior, where it mentions sushi as "a roll of cold rice with fish, sea-weed, or some other flavoring".[23][24] There is an earlier mention of sushi in James Hepburn's Japanese–English dictionary from 1873,[25] and an 1879 article on Japanese cookery in the journal Notes and Queries.[26] Despite common misconception among English speakers, sushi does not mean "raw seafood."[27]

Types

[edit]

The common ingredient in all types of sushi is vinegared sushi rice. Fillings, toppings, condiments, and preparation vary widely.[28]

Due to rendaku consonant mutation, sushi is pronounced with zu instead of su when a prefix is attached, as in nigirizushi.

Chirashizushi

[edit]

Chirashizushi (ちらし寿司, "scattered sushi"; also referred to as barazushi) serves the rice in a bowl and tops it with a variety of raw fish and vegetable garnishes. It is popular because it is filling, fast, and easy to make.[29] It is eaten annually on Hinamatsuri in March and Children's Day in May.

- Edomae chirashizushi (Edo-style scattered sushi) is served with uncooked ingredients in an artful arrangement.

- Gomokuzushi (Kansai-style sushi) consists of cooked or uncooked ingredients mixed in the body of rice.

- Sake-zushi (Kyushu-style sushi) uses rice wine over vinegar in preparing the rice and is topped with shrimp, sea bream, octopus, shiitake mushrooms, bamboo shoots, and shredded omelette.

Inarizushi

[edit]

Inarizushi (稲荷寿司) is a pouch of fried tofu typically filled with sushi rice alone. According to Shinto lore, inarizushi is named after the god Inari. Foxes, messengers of Inari, are believed to have a fondness for fried tofu and in some regions an Inari-zushi roll has pointed corners that resemble fox ears, thus reinforcing the association.[30] The shape of Inarizushi varies by region. Inarizushi usually has a rectangular shape in Kantō region and a triangle shape in the Kansai region.[31]

Regional variations include pouches made from a thin omelette (帛紗寿司, fukusa-zushi or 茶巾寿司, chakin-zushi), instead of fried tofu. It should not be confused with inari maki, a sushi roll filled with seasoned fried tofu.[32][33]

Cone sushi is a variant of inarizushi originating in Hawaii that may include green beans, carrots, gobo, or poke along with rice, wrapped in a triangular abura-age piece. It is often sold in okazu-ya (Japanese delis) and as a component of bento boxes.[34][35]

Makizushi

[edit]Makizushi (巻き寿司, "rolled sushi"), norimaki (海苔巻き, "nori roll"; used generically for other dishes as well) or makimono (巻物, "variety of rolls") is a cylindrical piece formed with the help of a mat known as a makisu (巻き簾). Makizushi is generally wrapped in nori (seaweed) but is occasionally wrapped in a thin omelette, soy paper, cucumber, or shiso (perilla) leaves. Makizushi is often cut into six or eight pieces, constituting a single roll order. Short-grain white rice is usually used, although short-grain brown rice, like olive oil on nori, is now becoming more widespread among the health-conscious. Rarely, sweet rice is mixed in makizushi rice.

Nowadays, the rice in makizushi can be many kinds of black rice, boiled rice, and cereals. Besides the common ingredients listed above, some varieties may include cheese, spicy cooked squid, yakiniku, kamaboko, lunch meat, sausage, bacon or spicy tuna. The nori may be brushed with sesame oil or sprinkled with sesame seeds. In a variation, sliced pieces of makizushi may be lightly fried with egg coating.

Below are some common types of makizushi, but many other kinds exist.

- Futomaki (太巻, "thick, large, or fat rolls") is a large, cylindrical style of sushi, usually with nori on the outside.[36] A typical futomaki is five to six centimeters (2 to 2+1⁄2 in) in diameter.[37] They are often made with two, three, or more fillings that are chosen for their complementary tastes and colors. Futomaki are often vegetarian, and may use strips of cucumber, kampyō gourd, takenoko (bamboo shoots), or lotus root. Strips of tamagoyaki omelette, tiny fish roe, chopped tuna, and oboro whitefish flakes are typical non-vegetarian fillings.[36] Traditionally, the vinegared rice is lightly seasoned with salt and sugar. Popular proteins are fish cakes, imitation crab meat, egg, tuna, or shrimp. Vegetables usually include cucumber, lettuce, and takuan (沢庵, pickled radish).

- Tamago makizushi (玉子巻き寿司) is makizushi is wrapped in a thin omelet.

- Tempura makizushi (天ぷら 巻き寿司) or agezushi (揚げ寿司ロール) is a fried version of the dish.

- During the evening of the festival of Setsubun (節分), it is traditional in the Kansai region to eat a particular kind of futomaki in its uncut cylindrical form, called ehōmaki (惠方巻, "lucky direction roll").[38] By 2000 the custom had spread to all of Japan.[39] Ehōmaki is a roll composed of seven ingredients considered to be lucky. The typical ingredients include kanpyō, egg, eel, and shiitake mushroom. Ehōmaki often include other ingredients too. People usually eat the ehōmaki while facing the direction considered to be auspicious that year.[40]

- Hosomaki (細巻, "thin rolls") is a type of small cylindrical sushi with nori on the outside. A typical hosomaki has a diameter of about 2.5 centimeters (1 in).[37] They generally contain only one filling, often tuna, cucumber, kanpyō, nattō, umeboshi paste, and squid with shiso (Japanese herb).

- Kappamaki (河童巻) is a kind of hosomaki filled with cucumber. It is named after the Japanese legendary water imp, fond of cucumbers, called the kappa. Traditionally, kappamaki is consumed to clear the palate between eating raw fish and other kinds of food so that the flavors of the fish are distinct from the tastes of other foods.

- Tekkamaki (鉄火巻) is a kind of hosomaki filled with raw tuna. Although it is believed that the word tekka, meaning "red hot iron", alludes to the color of the tuna flesh or salmon flesh, it actually originated as a quick snack to eat in gambling dens called tekkaba (鉄火場), much like the origins of the sandwich.[41][42]

- Negitoromaki (ねぎとろ巻) is a kind of hosomaki filled with negitoro, also known as scallion (negi) and chopped tuna (toro). Fatty tuna is often used in this style.

- Tsunamayomaki (ツナマヨ巻) is a kind of hosomaki filled with canned tuna tossed with mayonnaise.

- Temaki (手巻, "hand roll") is a large cone-shaped style of sushi with nori on the outside and the ingredients spilling out the wide end. A typical temaki is about 10 centimeters (4 in) long and is eaten with the fingers because it is too awkward to pick it up with chopsticks. For optimal taste and texture, temaki must be eaten quickly after being made because the nori cone soon absorbs moisture from the filling and loses its crispness, making it somewhat difficult to bite through. For this reason, the nori in pre-made or take-out temaki is sealed in plastic film, which is removed immediately before eating.[43]

-

Makizushi topped with tobiko

-

Makizushi in preparation

-

Futomaki

-

Temaki

-

Kappamaki

-

Nattōmaki

-

Tekkamaki

-

Ehōmaki

Modern narezushi

[edit]

Narezushi (熟れ寿司, "matured sushi") is a traditional form of fermented sushi. Skinned and gutted fish are stuffed with salt, placed in a wooden barrel, doused with salt again, then weighed down with a heavy tsukemonoishi (pickling stone). As days pass, water seeps out and is removed. After six months, this sushi can be eaten, remaining edible for another six months or more.[44]

The most famous variety of narezushi are the ones offered as a specialty dish of Shiga Prefecture,[45] particularly the funa-zushi made from fish of the crucian carp genus, the authentic version of which calls for the use of nigorobuna, a particular locally differentiated variety of wild goldfish endemic to Lake Biwa.[46]

Nigirizushi

[edit]

Nigirizushi (握り寿司, "hand-pressed sushi") consists of an oblong mound of sushi rice that a chef typically presses between the palms of the hands to form an oval-shaped ball and a topping (the neta) draped over the ball. It is usually served with a bit of wasabi; toppings are typically fish such as salmon, tuna, or other seafood. Certain toppings are typically bound to the rice with a thin strip of nori, most commonly octopus (tako), freshwater eel (unagi), sea eel (anago), squid (ika), and sweet egg (tamago).

Gunkanmaki (軍艦巻, "warship roll") (ja:軍艦巻) is a special type of nigirizushi: an oval, hand-formed clump of sushi rice that has a strip of nori wrapped around its perimeter to form a vessel that is filled with some soft, loose or fine-chopped ingredient that requires the confinement of nori such as roe, nattō, oysters, uni (sea urchin roe), sweetcorn with mayonnaise, scallops, and quail eggs. Gunkan-maki was invented at the Ginza Kyubey restaurant in 1941; its invention significantly expanded the repertoire of soft toppings used in sushi.[47][48]

Temarizushi (手まり寿司, "ball sushi") is a style of sushi made by pressing rice and fish into a ball-shaped form by hand using a plastic wrap.

Oshizushi

[edit]

Oshizushi (押し寿司, "pressed sushi"), also known as hako-zushi (箱寿司, "box sushi"), is a pressed sushi from the Kansai region, a favorite and specialty of Osaka. A block-shaped piece is formed using a wooden mold, called an oshibako. The chef lines the bottom of the oshibako with the toppings, covers them with sushi rice, and then presses the mold's lid to create a compact, rectilinear block. The block is removed from the mold and then cut into bite-sized pieces. Particularly famous is battera (バッテラ, pressed mackerel sushi) or saba zushi (鯖寿司).[49] In oshizushi, all the ingredients are either cooked or cured, and raw fish is never used.[50] The name battera means "small boat" in Portuguese (bateira), as the sushi molds resembled small boats.[51]

Oshizushi wrapped in persimmon leaves, a specialty of Nara, is known as kakinohazushi (柿の葉寿司).

Seared oshizushi, or aburi oshizushi (炙り押し寿司), is a popular variety invented in Vancouver, British Columbia in 2008.[52][53][54] This involves using a butane torch to sear the sushi, which may contain ingredients such as mayonnaise, various sauces, jalapeños, and avocado in addition to typical sushi ingredients such as salmon and mackerel. The variety has since spread to other cities, such as Toronto.[55]

Western-style sushi

[edit]

The increasing popularity of sushi worldwide has resulted in variations typically found in the Western world but rarely in Japan.

One widespread form of sushi created to suit the Western palate is the California roll, a norimaki which presently almost always uses imitation crab (the original recipe calls for real cooked crab), along with avocado and cucumber.[57] A wide variety of popular rolls (norimaki and uramaki) have evolved since.

The identity of the creator of the California roll is disputed. Several chefs from Los Angeles have been cited as the dish's originators, as well as one chef from Vancouver, British Columbia.[58]

The earliest mention in print of a "California roll" was in the Los Angeles Times and an Ocala, Florida newspaper on November 25, 1979.[59] Less than a month later an Associated Press story credited a Los Angeles chef named Ken Seusa at the Kin Jo sushi restaurant near Hollywood as its inventor. The AP article cited Mrs. Fuji Wade, manager of the restaurant, as its source for the claim.[59]

Others[60][61][62] attribute the dish to Ichiro Mashita, another Los Angeles sushi chef from the former Little Tokyo restaurant "Tokyo Kaikan".[63] According to this account, Mashita began substituting the toro (fatty tuna) with avocado in the off-season, and after further experimentation, developed the prototype, back in the 1960s.[64]

Japanese-born chef Hidekazu Tojo, a resident of Vancouver, British Columbia since 1971 is also credited,[60][61][62] claiming he created the California roll at his restaurant in the late 1970s.[65] Tojo insists he is the innovator of the "inside-out" sushi, and it got the name "California roll" because its contents of crab and avocado were abbreviated to C.A., which is the abbreviation for the state of California. Because of this coincidence, Tojo was set on the name California Roll. According to Tojo, he single-handedly created the California roll at his Vancouver, British Columbia restaurant, including all the modern ingredients of cucumber, cooked crab, and avocado.[66] In 2016 the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries named Tojo a goodwill ambassador for Japanese cuisine.[67]

The common theme in origin stories is that surrounding the roll in rice made it more appealing to western consumers who had never eaten traditional sushi. This innovation led to the eventual creation of countless rolls across North America and the world.[citation needed]

For example, the "Norway roll" is another variant of uramakizushi filled with tamago (omelette), imitation crab and cucumber, rolled with shiso leaf and nori, topped with slices of Norwegian salmon, garnished with lemon and mayonnaise.[68]

Although most Western sushi creations are rare in Japan, a notable exception to this is the use of salmon. The Japanese have eaten salmon since prehistory; however, caught salmon in nature often contains parasites and must be cooked or cured for its lean meat to be edible. On the other side of the world, in the 1960s and 1970s, Norwegian entrepreneurs started experimenting with aquaculture farming. The big breakthrough was when they figured out how to raise salmon in net pens in the sea. Being farm-raised, the Atlantic salmon reportedly showed advantages over the Pacific salmon, such as no parasites, easy animal capture, and higher fat content. With government subsidies and improved techniques, they were so successful in raising fatty and parasite-free salmon they ended up with a surplus. Norway has a small population and limited market; therefore, they looked to other countries to export their salmon. The first Norwegian salmon was imported into Japan in 1980, accepted conventionally, for grilling, not for sushi. Salmon had already been consumed in North America as an ingredient in sushi as early as the 1970s.[69][70][71] Salmon sushi did not become widely accepted in Japan until a successful marketing partnership in the late 1980s between Bjørn E. Olsen, a Norwegian businessman tasked with helping the Norwegian salmon industry glut, and the Japanese food supplier Nichirei.[72][73][56]

Uramaki

[edit]

Uramaki (裏巻, "inside-out roll") is a medium-sized cylindrical style of sushi with two or more fillings and was developed as a result of the creation of the California roll, as a method originally meant to hide the nori. Uramaki differs from other makimono because the rice is on the outside and the nori inside. The filling is surrounded by nori, then a layer of rice, and optionally an outer coating of some other ingredients such as roe or toasted sesame seeds. It can be made with different fillings, such as tuna, crab meat, avocado, mayonnaise, cucumber, or carrots.

Examples of variations include the rainbow roll (an inside-out topped with thinly sliced maguro, hamachi, ebi, sake and avocado) and the caterpillar roll (an inside-out topped with thinly sliced avocado). Also commonly found is the "rock and roll" (an inside-out roll with barbecued freshwater eel and avocado with toasted sesame seeds on the outside).

In Japan, uramaki is an uncommon type of makimono; because sushi is traditionally eaten by hand in Japan, the outer layer of rice can be quite difficult to handle with fingers.[74]

In Brazil uramaki and other sushi pieces commonly include cream cheese in their recipe. Although unheard of in Japanese sushi, this is the most common sushi ingredient used in Brazil. Temaki also often contains a large amount of cream cheese and is extremely popular in restaurants.[75]

American-style makizushi

[edit]

Multiple-filling rolls inspired by futomaki are a more popular type of sushi within the United States and come in variations that take their names from their places of origin. Other rolls may include a variety of ingredients, including chopped scallops, spicy tuna, beef or chicken teriyaki roll, okra, and assorted vegetables such as cucumber and avocado, and the tempura roll, where shrimp tempura is inside the roll or the entire roll is battered and fried tempura-style. In the Southern United States, many sushi restaurants prepare rolls using crawfish. Sometimes, rolls are made with brown rice or black rice, known as forbidden rice, which appear in Japanese cuisine as well.

Per Food and Drug Administration regulations, raw fish served in the United States must be frozen before serving to kill parasites.[76]

Since rolls are often made to order, it is not unusual for the customer to specify the exact ingredients desired (e.g., salmon roll, cucumber roll, avocado roll, tuna roll, shrimp or tuna tempura roll, etc.). Though the menu names of dishes often vary by restaurant, some examples include the following:

| Image | Sushi roll name | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Alaskan roll | A variant of the California roll with smoked salmon on the inside or layered on the outside.[77] | |

| Boston roll | An uramaki California roll with poached shrimp instead of imitation crab.[78] | |

|

British Columbia roll | A roll containing grilled or barbecued salmon skin, cucumber, and sweet sauce, sometimes with roe. Also sometimes referred to as salmon skin rolls outside of British Columbia, Canada.[79] |

|

California roll | A roll consisting of avocado, kani kama (imitation crab/crab stick) (also can contain real crab in "premium" varieties), cucumber, and tobiko, often made as uramaki (with rice on the outside, nori on the inside).[80] |

|

Dragon roll | A roll containing fillings such as shrimp tempura, cucumber, and unagi, and wrapped distinctively with avocado on the outside. Also commonly called a "caterpillar roll", its avocado exterior is said to resemble the scales of a dragon.[81] |

|

Dynamite roll | A roll including yellowtail (hamachi) or prawn tempura, and fillings such as bean sprouts, carrots, avocado, cucumber, chili, spicy mayonnaise, and roe.[82] |

| Hawaiian roll | A roll containing shōyu tuna (canned), tamago, kanpyō, kamaboko, and the distinctive red and green hana ebi (shrimp powder).[83] | |

| Mango roll | A roll including fillings such as avocado, crab meat, tempura shrimp, and mango slices, and topped off with a creamy mango paste.[84] | |

| Michigan roll | A roll including fillings such as spicy tuna, smelt roe, spicy sauce, avocado, and sushi rice. It is a variation on a spicy tuna roll.[85] | |

| New Mexico roll | A roll originating in New Mexico; includes New Mexico green chile (sometimes tempura-fried), teriyaki sauce, and rice.[86][87] Sometimes simply referred to as a "green chile (tempura) roll" within the state.[88][89] | |

|

Philadelphia roll | A roll consisting of raw or smoked salmon and cream cheese (the name refers to Philadelphia cream cheese), with cucumber, avocado, and/or scallion.[90] Functionally synonymous with Japanese bagel (JB) roll and Seattle roll.[91] |

|

Rainbow roll | A California uramaki roll with multiple types of fish (commonly yellowtail, tuna, salmon, snapper, white fish, eel, etc.) and avocado wrapped around it.[92] |

|

Spicy tuna roll | A roll including raw tuna mixed with sriracha mayonnaise. |

|

Spider roll | A roll including fried soft-shell crab and other fillings such as cucumber, avocado, daikon sprouts or lettuce, roe, and sometimes spicy mayonnaise.[93] |

|

Sushi burrito | A large, customizable roll offered in several "sushi burrito" restaurants in the United States.[94] |

Australia

[edit]Australian sushi is a thick hand roll made from half a standard sheet of nori. It is similar to futomaki thick rolls; however, it is often served uncut as an on-the-go snack.[95] Typical fillings in Australian sushi include teriyaki chicken, salmon and avocado, tuna, and prawn.[96] Australian California rolls are very different from American California rolls, with the nori wrapping the rice and fillings always on the outside, and no tobiko nor cream cheese.

Contrary to sushi in Japan and other countries being a high-end food, it is widely available in affordable takeaway joints in Australia.[97] Sushi in Japanese restaurants has existed in Australia since the 1950s, but the first Australian-style sushi only appeared in 1995, in a stall called Sushi-Jin in the Target Centre food court at 246 Bourke Street, Melbourne. The owner, Toshihiro Shindo, started selling takeaway sushi rolls which he adapted to Australian tastes. The store closed in 2008.[98] As of 2024, Japanese cuisine is the most popular cuisine in Australia with sushi as the third overall most popular food item, after hot dogs and pizza.[99]

Australian sushi has grown in popularity in recent years, with its influence extending beyond Australia into the United Kingdom[100] and United States, which has sparked an online controversy after the opening of Sushi Counter in West Village, New York City. People accused the owner of cultural appropriation and left negative reviews,[101][102] prompting Google to remove all spam ratings from the restaurant location.

Canada

[edit]

Many of the styles seen in the United States are also seen in Canada and their own. Doshi (a portmanteau of donut and sushi) is a donut-shaped rice ball on a deep-fried crab or imitation crab cake topped with sushi ingredients.[103] Maki poutine is similar to makizushi in style except it is topped with cheese curds and gravy and contains duck confit, more cheese curds, and sweet potato tempura.[104] Sushi cake is made of crab meat, avocado, shiitake mushroom, salmon, spicy tuna, and tobiko and served on sushi rice, then torched with spicy mayonnaise, barbecue sauce, and balsamic reduction, and dotted with caper and garlic chips.[105] Sushi pizza is deep-fried rice or crab/imitation crab cake topped with mayonnaise and various sushi ingredients.[106]

Mexico and the Western United States

[edit]Sinaloan sushi originated in Sinaloa, Mexico and has been available in the Western United States since 2013.[107]

Similar dishes in Asia

[edit]South Korea

[edit]Gimbap, similar to makizushi, is an internationally popular convenience food of Korean origin.[108] It consists of gim (the Korean version of nori) rolled around rice seasoned with sesame oil, instead of vinegar, and a variety of ingredients such as vegetables, like danmuji, and meat, like bulgogi.[109]

Ingredients

[edit]

All sushi has a base of specially prepared rice, complemented with other ingredients. Traditional Japanese sushi consists of rice flavored with vinegar sauce and various raw or cooked ingredients.

Sushi-meshi

[edit]Sushi-meshi (鮨飯) (also known as su-meshi (酢飯), shari (舎利), or gohan (ご飯)) is a preparation of white, short-grained, Japanese rice mixed with a dressing consisting of rice vinegar, sugar, salt, and occasionally kombu and sake. It must be cooled to room temperature before being used for a sushi filling, or it will get too sticky while seasoned. Traditionally, it is mixed with a hangiri (a round, flat-bottom wooden tub or barrel) and a shamoji (a wooden paddle).

Sushi rice is prepared with short-grain Japanese rice, which has a consistency that differs from long-grain strains such as those from India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Thailand, and Vietnam. The essential quality is its stickiness or glutinousness, although the type of rice used for sushi differs from glutinous rice. Freshly harvested rice (shinmai) typically contains too much water and requires extra time to drain the rice cooker after washing. In some fusion cuisine restaurants, short-grain brown rice and wild rice are also used.

There are regional variations in sushi rice, and individual chefs have their methods. Most of the variations are in the rice vinegar dressing: the Kantō region (or East Japan) version of the dressing commonly uses more salt; in Kansai region (or West Japan), the dressing has more sugar.

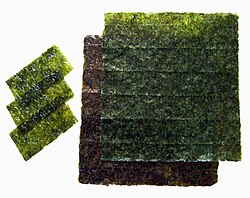

Nori

[edit]

The dark green seaweed wrappers used in makimono are called nori (海苔). Nori is a type of red algae, typically in the family Bangiaceae, traditionally cultivated in the harbors of Japan. Many different foliose red algae species are cultivated to be used as sushi wrappers, however Pyropia tenera is the most commonly farmed. This species ranks among the top three most commonly cultivated seaweed species in China, Korea, and Japan.[110] Originally, algae was scraped from dock pilings, rolled out into thin, edible sheets, and dried in the sun, similar to making rice paper.[111] Today, the commercial product is farmed, processed, toasted, packaged, and sold in sheets.

The size of a nori sheet influences the size of makimono. A full-size sheet produces futomaki, and a half produces hosomaki and temaki. To produce gunkan and some other makimono, an appropriately sized piece of nori is cut from a whole sheet.

Nori by itself is an edible snack and is available with salt or flavored with teriyaki sauce. The flavored variety, however, tends to be of lesser quality and is not suitable for sushi.

When making fukusazushi, a paper-thin omelet may replace a sheet of nori as the wrapping. The omelet is traditionally made on a rectangular omelet pan, known as a makiyakinabe, and used to form the pouch for the rice and fillings.[112]

Gu

[edit]

The ingredients used inside sushi are called gu and are, typically, varieties of fish.[113] For culinary, sanitary, and aesthetic reasons, the minimum quality and freshness of fish to be eaten raw must be superior to that of fish that is to be cooked. Sushi chefs are trained to recognize important attributes, including smell, color, firmness, and freedom from parasites that may go undetected in a commercial inspection. Commonly used fish are tuna (maguro, shiro-maguro), yellowtail (hamachi), snapper (kurodai), mackerel (saba), and salmon (sake). The most valued sushi ingredient is toro, the fatty cut of the fish.[114] This comes in a variety of ōtoro (often from the bluefin species of tuna) and chūtoro, meaning "middle toro", implying that it is halfway into the fattiness between toro and the regular cut. Aburi style refers to nigiri sushi, where the fish is partially grilled (topside) and partially raw. Most nigiri sushi will have completely raw toppings, called neta.[113]

Other seafoods such as squid (ika), eel (anago and unagi), pike conger (hamo), octopus (tako), shrimp (ebi and amaebi), clam (mirugai, aoyagi and akagai), fish roe (ikura, masago, kazunoko and tobiko), sea urchin (uni), crab (kani), and various kinds of shellfish (abalone, prawn, scallop) are the most popular seafoods in sushi. Oysters are less common, as the taste is thought to not go well with the rice. Kani kama, or imitation crab stick, is commonly substituted for real crab, most notably in California rolls.[115]

Pickled daikon radish (takuan) in shinko maki, pickled vegetables (tsukemono), fermented soybeans (nattō) in nattō maki, avocado, cucumber in kappa maki, asparagus,[116] yam, pickled ume (umeboshi), gourd (kanpyō), burdock (gobo), and sweet corn (sometimes mixed with mayonnaise) are plant products used in sushi.

Tofu, eggs (in the form of slightly sweet, layered omelette called tamagoyaki), and raw quail eggs (as a gunkan-maki topping) are also common.

Condiments

[edit]Sushi is commonly eaten with condiments. Sushi may be dipped in shōyu (soy sauce), and is usually flavored with wasabi, a piquant paste made from the grated stem of the Wasabia japonica plant. Japanese-style mayonnaise is a common condiment in Japan on salmon, pork, and other sushi cuts.

The traditional grating tool for wasabi is a sharkskin grater or samegawa oroshi. An imitation wasabi (seiyo-wasabi), made from horseradish, mustard powder, and green dye, is common. It is found at lower-end kaiten-zushi restaurants, in bento box sushi, and at most restaurants outside Japan. If manufactured in Japan, it may be labelled "Japanese Horseradish".[117] The spicy compound in both true and imitation wasabi is allyl isothiocyanate, which has well-known anti-microbial properties. However, true wasabi may contain some other antimicrobials as well.[118]

Gari (sweet, pickled ginger) is eaten in between sushi courses to both cleanse the palate and aid in digestion. In Japan, green tea (ocha) is invariably served together with sushi. Better sushi restaurants often use a distinctive premium tea known as mecha. In sushi vocabulary, green tea is known as agari.

Sushi may be garnished with gobo, grated daikon, thinly sliced vegetables, carrots, radishes, and cucumbers that have been shaped to look like flowers, real flowers, or seaweed salad.

When closely arranged on a tray, different pieces are often separated by green strips called baran or kiri-zasa (切り笹). These dividers prevent the flavors of neighboring pieces of sushi from mixing and help to achieve an attractive presentation. Originally, these were cut leaves from the Aspidistra elatior (葉蘭, haran) and Sasa veitchii (熊笹, kuma-zasa) plants, respectively. Using actual leaves had the added benefit of releasing antimicrobial phytoncides when cut, thereby extending the limited shelf life of the sushi.[119]

Sushi bento boxes are a staple of Japanese supermarkets and convenience stores. As these stores began rising in prominence in the 1960s, the labor-intensive cut leaves were increasingly replaced with green plastic to lower costs. This coincided with the increased prevalence of refrigeration, which extended sushi's shelf life without the need for cut leaves. Today plastic strips are commonly used in sushi bento boxes and, to a lesser degree, in sushi presentations found in sushi bars and restaurants. In store-sold or to-go packages of sushi, the plastic leaf strips are often used to prevent the rolls from coming into early or unwanted contact with the ginger and wasabi included with the dish.[120]

Nutrition

[edit]

The main ingredients of traditional Japanese sushi—raw fish and rice—are naturally low in fat and high in protein, carbohydrates (from the rice), vitamins, and minerals, as are gari (pickled ginger) and nori (seaweed). Other vegetables wrapped in sushi may also provide additional nutrients.[121]

Health risks

[edit]Potential chemical and biological hazards in sushi include environmental contaminants, pathogens, and toxins.

Large marine apex predators such as tuna (especially bluefin) can harbor high levels of methylmercury, one of many toxins of marine pollution. Frequent or significantly large consumption of methylmercury can lead to developmental defects when consumed by certain higher-risk groups, including women who are pregnant or may become pregnant, nursing mothers, and young children.[122] A 2021 study in Catalonia, Spain reported that the estimated exposure to methylmercury in sushi consumption by adolescents exceeded the tolerable daily intake.[123]

A 2011 article reported approximately 18 million people infected with fish-borne flukes worldwide.[124] Such an infection can be dangerous for expecting mothers due to the health risks that medical interventions or treatment measures may pose on the developing fetus.[124] Parasitic infections can have a wide range of health impacts, including bowel obstruction, anemia, liver disease, and more.[124] These illnesses' impact can pose health concerns for the expecting mother and baby.[124]

Sashimi or other types of sushi containing raw fish present a risk of infection by three main types of parasites:

- Clonorchis sinensis, a fluke which can cause clonorchiasis[125]

- Anisakis, a roundworm which can cause anisakiasis[126]

- Diphyllobothrium, a tapeworm which can cause diphyllobothriasis[127]

For these reasons, EU regulations forbid using raw fish that had not previously been frozen. It must be frozen at temperatures below −20 °C (−4 °F) in all product parts for no less than 24 hours.[128] Fish for sushi may be flash frozen on fishing boats and by suppliers to temperatures as low as −60 °C (−76 °F).[129] Super-freezing destroys parasites, and also prevents oxidation of the blood in tuna flesh that causes discoloration at temperatures above −20 °C (−4 °F).[130]

Calls for stricter analysis and regulation of seafood include improved product description. A 2021 DNA study in Italy found 30%–40% of fish species in sushi incorrectly described.[131]

Some forms of sushi, notably those containing the fugu pufferfish and some kinds of shellfish, can cause severe poisoning if not prepared properly. Fugu consumption, in particular, can be fatal. Fugu pufferfish have a lethal dose of tetrodotoxin in their internal organs and, by law in many countries, must be prepared by a licensed fugu-chef who has passed the prefectural examination in Japan.[132] Licensing involves a written test, a fish-identification test, and a practical test that involves preparing the fugu and separating out the poisonous organs; only about 35 percent of applicants pass.[133]

Sustainable sushi

[edit]Sustainable sushi is made from fished or farmed sources that can be maintained or whose future production does not significantly jeopardize the ecosystems from which it is acquired.

Presentation

[edit]

Traditionally, sushi is served on minimalist Japanese-style plates—often made of wood or lacquer—and arranged to emphasize clean lines, open space, and a sense of tranquility, reflecting the aesthetic principles of Japanese cuisine.[134]

Many sushi restaurants offer fixed-price sets selected by the chef from the catch of the day.[135] These are often graded as shō-chiku-bai (松竹梅), shō/matsu (松, pine), chiku/take (竹, bamboo), and bai/ume (梅, plum), with matsu being the most expensive and ume the least expensive.[136] Sushi restaurants often have private booth dining, where guests are asked to remove their shoes and leave them outside the room;[137] however, most sushi bars offer diners a casual experience with an open dining room concept.[138]

Sushi may also be served kaiten zushi (sushi train) style, in which color-coded plates of sushi are placed on a conveyor belt from which diners pick as they please.[139] After finishing, the bill is tallied by counting how many plates of each color have been taken. Newer kaiten zushi restaurants use barcodes or RFID tags embedded in the dishes to manage the time elapsed since each item was prepared.[140]

There is a practice called nyotaimori which entails serving sushi on the naked body of a woman.[141][142][143]

Glossary

[edit]Some specialized or slang terms are used in the sushi culture. Most of these terms are used only in sushi bars.

- Agari: lit. 'Rise up', refers to green tea. Ocha (お茶) in usual Japanese.

- Gari: Sweet, pickled and sliced ginger, or sushi ginger (gari). Shōga (生姜) in standard Japanese.

- Gyoku: "Jewel". Sweet, cube-shaped omelette. 卵焼, 玉子焼 (Tamagoyaki) in standard Japanese.

- Murasaki: "Violet" or "purple" (color). Soy sauce. Shōyu (醤油) in standard Japanese.

- Neta: Toppings on nigiri or fillings in makimono. A reversal of the standard Japanese tane (種).

- Oaiso: "Compliment". Bill or check. Oaiso may be used in not only sushi bars but also izakaya.[144][145] Okanjō (お勘定) or chekku (チェック) in standard Japanese.

- Otemoto: Chopsticks.7 Otemoto means the nearest thing to the customer seated. Hashi (箸) or ohashi in standard Japanese.

- Sabi: Contracted form of wasabi (山葵), also known as Japanese horseradish.

- Shari: Vinegar rice or rice. It may originally be from the Sanskrit zaali (शालि) meaning rice, or Śarīra. Gohan (ご飯)) or meshi (飯) in standard Japanese.

- Tsume: Sweet thick sauce mainly made of soy sauce. Nitsume (煮詰め) in standard Japanese.[146]

Etiquette

[edit]Unlike sashimi, which is almost always eaten with chopsticks, nigirizushi is traditionally eaten with the fingers, even in formal settings.[147] Although it is commonly served on a small platter with a side dish for dipping, sushi can also be served in a bento, a box with small compartments that hold the various dishes of the meal.

Soy sauce is the usual condiment, and sushi is normally served with a small sauce dish or a compartment in the bento. Traditional etiquette suggests that the sushi is turned over so that only the topping is dipped to flavor it; the rice—which has already been seasoned with rice wine vinegar, sugar, salt, mirin, and kombu—would otherwise absorb too much soy sauce and would fall apart.[148]

Traditionally, the sushi chef will add an appropriate amount of wasabi to the sushi while preparing it, and the diner should not add more.[148] However, today, wasabi is more a matter of personal taste, and even restaurants in Japan may serve wasabi on the side for customers to use at their discretion, even when there is wasabi already in the dish.[149]

Utensils used in making sushi

[edit]| Utensil | Definition |

|---|---|

| Fukin | Kitchen cloth |

| Hangiri | Rice barrel |

| Hocho | Kitchen knives |

| Makisu | Bamboo rolling mat |

| Ryoribashi or saibashi | Cooking chopsticks |

| Shamoji | Wooden rice paddle |

| Makiyakinabe | Rectangular omelette pan |

| Oshizushihako | A mold used to make oshizushi |

Gallery

[edit]-

Chu-Toro nigiri (中トロ寿司, Medium fatty tuna)

-

Salmon roll (巻き鮭)

-

Kakinoha (柿の葉寿司, persimmon leaf) sushi

-

Chakin-zushi (茶巾寿司), wrapped in thin omelette

-

Sushi plate (盛り合わせ)

-

Ikura gunkan-maki (イクラ軍艦巻き)

-

Sasa (笹寿司, bamboo leaf) sushi

-

Unagi (鰻寿司, teriyaki-roasted freshwater eel) sushi

-

Nigirizushi for sale at a supermarket in Tokyo

-

Assorted sushi (盛り合わせ)

-

Assorted Western sushi (盛り合わせ)

-

Western California roll and tuna roll uramaki (カリフォルニア巻き)

-

Western spicy tuna hand roll (スパイシーツナロール)

-

Western spicy shrimp roll (スパイシー海老ロール)

-

Gari (ginger)

-

Wasabi

-

Tamago sushi

-

Otoro sushi (鮪大トロ寿司)

See also

[edit]- Gimbap, Korean variant of makizushi

- Customs and etiquette in Japanese dining

- List of sushi and sashimi ingredients

- List of sushi restaurants

- Nyotaimori, sushi presented on nude female body

- Sashimi bōchō, Japanese knife to slice raw fish and seafood

- Spam musubi, Hawaiian variant of nigirizushi

- Sushi machine

References

[edit]- ^ "Sushi – How-To". FineCooking. May 1, 1998. Archived from the original on November 4, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ "The Mysteries of Sushi – Part 2: Fast Food". Toyo Keizai. May 23, 2015. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017.

- ^ "When Sushi Became a New Fast Food in Edo". Nippon.com. December 22, 2020. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021.

- ^ "Sushi". Nihonbashi. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021.

- ^ "Sashimi vs Sushi – Difference and Comparison | Diffen". www.diffen.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ a b Lee, Cherl-Ho; Steinkraus, Keith H; Reilly, P.J. Alan (1993). Fish fermentation technology. Tokyo: United Nation University Press. OCLC 395550059.

- ^ a b c d e Hirofumi Akano. "The evolution of sushi and the power of vinegar". Japan Science and Technology Agency. pp. 201, 202. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ Mouritsen, O. G. (2009). SUSHI food for the eye, the body & the soul (2nd ed.). Boston: Springer. p. 15. Bibcode:2009sfeb.book.....M. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0618-2. ISBN 978-1-4419-0617-5.

- ^ a b Sanchez, Priscilla C. (2008). "Lactic-Acid-Fermented Fish and Fishery Products". Philippine Fermented Foods: Principles and Technology. University of the Philippines Press. p. 264. ISBN 9789715425544.

- ^ Hill, Amelia (October 8, 2007). "Chopsticks at dawn for a sushi showdown". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 17, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2011.

- ^ Guerra, M.I. (1994). "Studies on tinapayan, an indigenous fish ferment in Central Mindanao (Philippines)". AGRIS. 1 (2): 364–365.

- ^ "Unveiling the origins of sushi: a journey through Vietnam". Tuoi Tre News. May 4, 2024. Retrieved May 10, 2024.

- ^ 1988, 国語大辞典(新装版) (Kokugo Dai Jiten, Revised Edition) (in Japanese), Tōkyō: Shogakukan

- ^ Kouji Itou; Shinsuke Kobayashi; Tooru Ooizumi; Yoshiaki Akahane (2006). "Changes of proximate composition and extractive components in narezushi, a fermented mackerel product, during processing". Fisheries Science. 72 (6): 1269–1276. Bibcode:2006FisSc..72.1269I. doi:10.1111/j.1444-2906.2006.01285.x. ISSN 0919-9268. S2CID 24004124.

- ^ a b Bestor, Theodore C. (July 13, 2004). Tsukiji: The Fish Market at the Center of the World. University of California Press. p. 141. ISBN 9780520923584.

- ^ 握りずし 始まりは江戸っ子のホットドッグスタンド (in Japanese). Nikkei, Inc. June 9, 2018. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ Mpritzen, Ole G. (2009). Sushi: Food for the Eye, the Body and the Soul. Springer Science-Business Media. p. 15.

- ^ Lowry, Dave (2010). The Connoisseur's Guide to Sushi. ReadHowYouWant.com. p. xvii. ISBN 978-1458764140. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

A nugget of rice was seasoned with vinegar and topped by a sliver of seafood fresh from the bay that was only a few blocks away. That is why a synonym for nigiri sushi is Edomae sushi: Edomae is "in front of Edo," i.e., the bay.

- ^ Mouritsen, Ole G. (2009). Sushi: Food for the Eye, the Body and the Soul. Springer. p. 17. ISBN 978-1441906182. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

Edomae-zushi or nigiri-zushi? Nigiri-zushi is also known as Edomae-zushi. Edomae refers to the small bay in Edo in front of the old palace that stood on the same site as the present-day imperial precinct in Tokyo. Fresh fish and shellfish caught in the bay were used locally to make sushi, known as Edomae-zushi. It has, however, been many years since these waters have been a source of seafood. Now the expression Edomae-zushi is employed as a synonym for high-quality nigiri-zushi.

- ^ a b Magnier, Mark (September 2, 2001). "Yoshiaki Shiraishi; Founded Conveyor Belt Sushi Industry". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ a b 回転寿司の歴史は半世紀超!回転寿司チェーン、それぞれの特徴は?. 寿司ウォーカー (in Japanese). Sushi walker. February 26, 2023. Archived from the original on February 14, 2024. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ a b 回転寿司の歴史 (in Japanese). Genroku Zushi. Archived from the original on December 1, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ^ "Sushi," Oxford English Dictionary, Second edition, 1989; online version December 2011. Accessed 23 December 2011.

- ^ Bacon, Alice Mabel (1893). A Japanese interior. Houghton, Mifflin and Company. p. 271.

p. 271: "Sushi, a roll of cold rice with fish, sea-weed, or some other flavoring" p. 181: "While we were waiting for my lord and my lady to appear, domestics served us with tea and sushi or rice sandwiches, and the year-old baby was brought in and exhibited." p. 180: "All the sushi that I had been unable to eat were sent out to my kuruma, neatly done in white paper."

- ^ James Curtis Hepburn, Japanese–English and English–Japanese dictionary, Publisher: Randolph, 1873, 536 pages (page 262)

- ^ W. H. Patterson, Japanese Cookery, "Notes and Queries," Publisher: Oxford University Press, 1879. (p.263 Archived 2016-02-02 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara (October 5, 2002). "Sushi Definition". Snopes. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Kawasumi, Ken (2001). The Encyclopedia of Sushi Rolls. Graph-Sha. ISBN 978-4-88996-076-1.

- ^ Adimando, Stacy (March 18, 2019). "Chirashi is Sushi for the Rest of Us". Saveur. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- ^ Smyers, Karen Ann. The Fox and the Jewel: Shared and Private Meanings in Contemporary Japanese Inari Worship (1999), Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, p. 96.

- ^ "根強い人気のいなり寿司はファストフード". 農林水産省.

- ^ "Other Sushi Styles". University of Edinburgh. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ "Fukusa Zushi". MakeSushi.com. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

- ^ Ann Kondo Corum, Ethnic Foods of Hawaii (2000). Bess Press: p. 54.

- ^ Joan Namkoong, Go Home, Cook Rice: A Guide to Buying and Cooking the Fresh Foods of Hawaii (2001). Ness Press: p. 8.

- ^ a b Ōmae, Kinjirō; Tachibana, Yuzuru (1988). The book of sushi (1st paperback ed.). Tokyo: Kōdansha International. p. 70. ISBN 9780870118661. OCLC 18925025.

- ^ a b Strada, Judi; Moreno, Mineko Takane (2004). Sushi for dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-7645-4465-1. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

Sliced sushi rolls are traditionally made in three different sizes, or diameters: thin 1-inch rolls (hoso-maki); medium 11⁄2-inch rolls (chu-maki); and thick 2 to 2+1⁄2-inch rolls (futo-maki)."

- ^ "Setsubun [節分]". Heisei Nippon seikatsu benrichō [平成ニッポン生活便利帳] (in Japanese). Tokyo: Jiyū Kokuminsha. 2012. Archived from the original on August 25, 2007. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ "Ehō-maki". Dijitaru daijisen (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. Archived from the original on August 25, 2007. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ "Setsubun Ehomaki, Mame-maki and Grilled Sardine". Kyoto Foodie. February 5, 2009. Archived from the original on August 7, 2014. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ Andy Bellin (March 2005). "Poker Night in Napa". Food & Wine. Archived from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- ^ Ryuichi Yoshii, "Tuna rolls (Tekkamaki)" Archived 2016-05-13 at the Wayback Machine, Sushi, p. 48 (1999), Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 962-593-460-X.

- ^ "Packaging For Temaki Sushi". Gpe.dk. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ Hosking, Richard (1997). A Dictionary of Japanese Food: Ingredients & Culture. Tuttle Publishing. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-8048-2042-4. Archived from the original on August 18, 2020. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ Lee, Cherl-Ho; Steinkraus, Keith H.; Reilly, P. J. Alan, eds. (1993). "Comparison of Fermented Foods of the East and West". Fish Fermentation Technology. United Nations University Press. p. 17. ISBN 9788970530031. OCLC 29195449. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

In Japan, the prototypical form remains mostly around Lake Biwa.

- ^ Hosking, Richard (1998), "From Lake and Sea. Goldfish and Mantis Shrimp Sushi", Fish: Food from the Waters, Oxford Symposium, pp. 160–161, ISBN 978-0-9073-2589-5, archived from the original on January 10, 2021, retrieved March 16, 2018

- ^ Chad Hershler (May 2005). "Sushi Then and Now". The Walrus. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010.

- ^ (ja) 軍カン巻の由来, お寿し大辞典 > お寿し用語集, 小僧寿しチェーン.

- ^ Ashkenazi, Michael; Jacob, Jeanne (2000). The essence of Japanese cuisine: an essay on food and culture. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-8122-3566-1. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

Called saba zushi or battera, after the Portuguese term for "small boat," which the mold resembles.

- ^ "Osaka Style Boxed Sushi". Sushi Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on January 16, 2008.

- ^ "Battera | Our Regional Cuisines : MAFF". www.maff.go.jp. Retrieved May 10, 2024.

- ^ "The origin of Vancouver's deep love for aburi sushi". The Georgia Straight. October 3, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "Chef's Table: Seigo Nakamura". NUVO Magazine. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "8 places to enjoy oshi sushi in Vancouver". The Daily Hive. November 30, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ "The best aburi sushi in Toronto". Taste Toronto. Retrieved May 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Jiang, Jess (September 18, 2015). "How the Desperate Norwegian Salmon Industry Created a Sushi Staple". Planet Money (blog/podcast). All Things Considered. NPR. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ Hsin-I Feng, Cindy (February 29, 2012). "The Tale of Sushi: History and Regulations". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 11 (2): 205–220. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00180.x. ISSN 1541-4337.

- ^ "The History of the California Roll". Michelin Guide. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

While many credit Los Angeles chefs with inventing the California roll, some accounts trace its creation to Vancouver-based chef Hidekazu Tojo, who popularized the inside-out roll style for Western palates.

- ^ a b Smith, Andrew F. (2012). American Tuna: The Rise and Fall of an Improbable Food. University of California Press. pp. 91. and notes 31 and 32.

- ^ a b "Sushi: The Story of the California Roll". FreshMAG US. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Tomicki, Hadley (October 24, 2012). "Will The Real Inventor of The California Roll Please Stand Up?". Grub Street. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ a b "The History Of The California Roll | International Drive Japanese Steakhouse And Seafood". www.shogunorlando.com. August 14, 2017. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ Austin, Allan W.; Ling, Huping, eds. (2015). Asian American history and culture: an encyclopedia. London New York: Routledge. p. 1265. ISBN 978-1-317-47644-3.

- ^ Corson, Trevor (2008). The story of sushi: an unlikely saga of raw fish and rice. New York: Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-088351-5.

- ^ "Meet the man behind the California roll". The Globe and Mail. October 23, 2012. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "The California Roll Was Invented in Canada | Ghostarchive". ghostarchive.org. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "Vancouver chef Tojo honoured by Japanese government". CBC.ca. The Canadian Press. June 10, 2016.

- ^ "Norway Roll of Umegaoka Sushi No Midori Sohonten Shibuya". Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ^ "Episode 651: The Salmon Taboo". NPR.org. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "How The Desperate Norwegian Salmon Industry Created A Sushi Staple". NPR.org. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Matsui, Akira (June 1, 2005). "Salmon Exploitation in Jomon Archaeology from a Wetlands Point of View". Journal of Wetland Archaeology. 5 (1): 49–63. Bibcode:2005JWetA...5...49M. doi:10.1179/jwa.2005.5.1.49. ISSN 1473-2971. S2CID 140720425. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Sollesnes, Oeystein (March 10, 2018). "The Norwegian campaign behind Japan's love of salmon sushi". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- ^ Norway Exports (April 8, 2011). "Norway's Introduction of Salmon Sushi to Japan". Nortrade. Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2015.

- ^ "Sushi Pioneers". SushiMasters. Archived from the original on April 11, 2013. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ^ "Tradição X modernidade na comida japonesa | O TEMPO". www.otempo.com.br. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ Julia Moskin (April 8, 2004). "Sushi Fresh From the Deep. .. the Deep Freeze". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

Most would be even more surprised to learn that if the sushi has not been frozen, it is illegal to serve it in the United States. Food and Drug Administration regulations stipulate that fish to be eaten raw – whether as sushi, sashimi, seviche, or tartare – must be frozen first to kill parasites.

- ^ "Alaska Roll". Sushi Sama. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "Boston Roll Recipe". Sushi Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ "What is a BC Roll?". The Sushi Index. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "California Roll". Sushi Sama. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "Dragon Roll Recipe - Sushi Roll Recipes - Sushi Encyclopedia". June 29, 2013. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ "Dynamite Roll Recipe". Japanese Sushi Recipes. Archived from the original on July 13, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Frisch, Eleanor. "Japanese and Western Types of Sushi". Food Service Warehouse. Archived from the original on November 15, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ De Laurentiis, Giada. "Crab, Avocado and Mango Roll". Food Network. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "Michigan Roll Recipe". The Sushi Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on January 17, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Romero, David (July 13, 2015). "Green chile prominently featured in sushi roll". KRQE. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ Garduño, Gil (October 29, 2011). "I Love Sushi – Albuquerque, New Mexico". Gil's Thrilling (And Filling) Blog. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ "Sushi order form". Japanese Kitchen Albuquerque. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ "Sushi order form". Nagomi Restaurant ABQ. Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ "Philadelphia Roll Recipe". Sushi Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on October 28, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "Spicy Seattle Tuna Rolls". Bon Appetit. July 12, 2011. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "Rainbow Roll Recipe". Sushi Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on June 27, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Moonen, Rick. "Spider Roll". Food Network. Archived from the original on November 17, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ Kearns, Landess (June 19, 2015). "Sushi Burritos Prove You Really Can Have It All". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- ^ Liaw, Adam (November 23, 2023). "Yes, 'Australian sushi' exists. Get over it, argues Adam Liaw". Good Food. The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ House, Moriah (June 30, 2024). "What Sets Australian-Style Sushi Apart From The Rest". The Takeout. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ Hariharan, Annie (June 23, 2020). "Cheap sushi and bountiful cheese: what stands out about eating in Australia". The Guardian. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ O'Connell, Jan (September 28, 1990). "Takeaway sushi in Australia - Australian food history timeline". Australian Food Timeline. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ Woodley, Melissa (June 3, 2024). "Australia's favourite cuisine has been revealed – and the results will make you hungry". TimeOut. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ Buccheri, Rory (September 8, 2024). "First Australian-style sushi on-the-go brand to open in Manchester". The Grocer. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Lauren (October 24, 2023). "Is it racist for a white woman to sell sushi?". www.spiked-online.com. Spiked. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ "Woman Called 'Coloniser' For Opening 'Australian-Style Sushi' Restaurant In New York". 10 play. Network 10. October 27, 2023. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ Peyton, Gabby (March 16, 2017). "10 questionable things Canada has done to sushi". DailyHIve. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Staff, DH Montreal (March 2, 2017). "You have to try this insane Montreal sushi dish". DailyHIve. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ William-Ross, Lindsay (March 10, 2017). "Where to have your Sushi Cake...and eat it, too". DailyHIve. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Chowhound (July 11, 2008). "Sushi Pizza- California specialty?! – General Discussion – Sushi". Chowhound. Archived from the original on November 3, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Bill Esparza (August 1, 2013), "Oh No, There Goes Tokyo Roll—Sinaloa Style Sushi Invades Los Angeles", Los Angeles Magazine

- ^ Alexander, Stian (January 21, 2016). "UK's new favourite takeaway has been revealed – and it's not what you'd think". Daily Mirror. Archived from the original on September 26, 2018. Retrieved February 26, 2017.

- ^ Cho, Joy (January 3, 2021). "Kimbap: Colorful Korean rolls fit for a picnic". Salon. Retrieved July 30, 2021.

- ^ Zhang, Lishu; et al. (October 13, 2022). "Global seaweed farming and processing in the past 20 years". Food Production, Processing and Nutrition. 4 (23): 2. doi:10.1186/s43014-022-00103-2.

- ^ Shimbo, Hiroko (November 8, 2000). The Japanese Kitchen: 250 Recipes in a Traditional Spirit. Harvard Common Press. p. 128. ISBN 9781558321779. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

Unlike wakame, kombu, and hijiki, which are sold in the form of individual leaves, nori is sold as a sheet made from small, soft, dark brown algae, which have been cultivated in bays and lagoons since the middle of the Edo Era (1600 to 1868). The technique of drying the collected algae on wooden frames was borrowed from the famous Japanese paper-making industry.

- ^ Pallett, Steven (2004). Simply sushi. Hinkler Books. p. 289. ISBN 9781741219722. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Lowry, Dave (2005). The Connoisseur's Guide to Sushi: Everything You Need to Know about Sushi Varieties and Accompaniments, Etiquette and Dining Tips, and More. Harvard Common Press. ISBN 9781558323070. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Andrew F. (August 8, 2012). American Tuna: The Rise and Fall of an Improbable Food. University of California Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780520261846. - Archived url, live status.

- ^ Rob Ludacer; Jessica Orwig. "Here's what imitation crab meat is really made of". Business Insider. Archived from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ Sakagami, Nick (June 4, 2019). Sushi Master: An expert guide to sourcing, making and enjoying sushi at home. Quarry Books. p. 87. ISBN 9781631596735. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Shimbo, Hiroko (2000). The Japanese Kitchen. Harvard Common Press. ISBN 978-1-55832-176-2.

- ^ Shin, I. S.; Masuda H.; Naohide K. (August 2004). "Bactericidal activity of wasabi (Wasabia japonica) against Helicobacter pylori". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 94 (3): 255–61. doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00297-6. PMID 15246236.

- ^ Gordenker, Alice (January 15, 2008). "Bento grass". The Japan Times Online. ISSN 0447-5763. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- ^ "Culinary Curiosities: That plastic leaf in sushi". CNN. June 21, 2010. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ "Sushi". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

Sushi typically combines low-fat fish, vinegared rice, and seaweed, offering a source of protein, carbohydrates, and essential minerals.

- ^ "Methylmercury: What You Need to Know About Mercury in Fish and Shellfish". Food and Drug Administration. March 1, 2004. Archived from the original on March 17, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ González, N; Correig, E; Marmelo, I; Marques, A; la Cour, R; Sloth, JJ; Nadal, M; Marquès, M; Domingo, JL (July 2021). "Dietary exposure to potentially toxic elements through sushi consumption in Catalonia, Spain". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 153 112285. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2021.112285. hdl:20.500.11797/imarina9216104. PMID 34023460. S2CID 235168607.

- ^ a b c d Jones, J.L.; Anderson, B.; Schulkin, J.; Parise, M. E.; Eberhard, M. L. (March 1, 2011). "Sushi in Pregnancy, Parasitic Diseases – Obstetrician Survey". Zoonoses and Public Health. 58 (2): 119–125. doi:10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01310.x. ISSN 1863-2378. PMID 20042060. S2CID 38590733. Archived from the original on November 6, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- ^ "Clonorchis sinensis – Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS)". Public Health Agency of Canada. February 18, 2011. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ "Parasites – Anisakiasis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 2, 2010. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ Dugdale, DC (August 24, 2011). "Fish tapeworm". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on July 4, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ European Parliament (April 30, 2004). "Regulation (EC) No 853/2004 of The European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 laying down specific hygiene rules for on the hygiene of foodstuffs" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. 139 (55): 133. Archived from the original on April 20, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ^ Issenberg, Sasha (2008). The sushi economy: globalization and the making of a modern delicacy. New York: Gotham. ISBN 978-1592403639.

- ^ Macfarlane, Alex. "The Truth About Sushi Fish". Everything Sushi Blog Interview. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2012.[self-published source]

- ^ Pappalardo, AM; Raffa, A; Calogero, GS; Ferrito, V (April 2, 2021). "Geographic Pattern of Sushi Product Misdescription in Italy-A Crosstalk between Citizen Science and DNA Barcoding". Foods. 10 (4): 756. doi:10.3390/foods10040756. PMC 8066630. PMID 33918119.

- ^ Warin, Rosemary H.; Steventon, Glyn B.; Mitchell, Steve C. (2007). Molecules of death. Imperial College Press. p. 390. ISBN 978-1-86094-814-5. Archived from the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ "One Man's Fugu Is Another's Poison". The New York Times. November 29, 1981. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

- ^ "The Art of Plating: Why Sushi Presentation Matters in Japanese Culture". KuruKuru Sushi Hawaii. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

In keeping with minimalist Japanese design, sushi plating avoids clutter. It emphasizes clean lines, open space, and a sense of tranquility.

- ^ "Kitchen Language: What Is Omakase?". Michelin Guide. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

Omakase is a form of Japanese dining in which guests leave themselves in the hands of a chef and receive a seasonal meal using the finest ingredients available.

- ^ "松・竹・梅のメニュー なぜ真ん中を選んでしまう?". Toshiba Tec (in Japanese). February 26, 2024. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

寿司屋やうなぎ屋などに行くと、「松4,000円」「竹2,500円」「梅1,500円」のように「松・竹・梅」に分かれたメニューを目にすることがあります。

- ^ "Eating at a Japanese Restaurant". Japan-Guide. June 1, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

In case of zashiki-style seating, you should remove your shoes at the entrance or before stepping onto the sitting area (tatami).

- ^ "Japanese Restaurants". Japan-Guide. June 1, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

In most sushi-ya, customers can sit either at a normal table or at a counter (sushi bar), behind which the sushi chef is working.

- ^ "Kaitenzushi (Conveyor Belt Sushi Restaurants)". Japan-Guide. June 1, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.

Kaitenzushi restaurants typically use plates of different colors and patterns to indicate their costs.

- ^ Ngai, E. W. T.; Suk, F. F. C.; Lo, S. Y. Y. (2008). "Development of an RFID-based sushi management system: The case of a conveyor-belt sushi restaurant". International Journal of Production Economics. 112 (2): 630–645. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2007.05.006.

- ^ Bindel, Julie (February 12, 2010). "'I am about to eat sushi off a naked woman's body'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 21, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Danovich, Tove (October 23, 2017). "Is Naked Sushi All About the Nigiri or the Nudity?". VICE. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Lin, Eddie (April 18, 2007). "Selling the Sizzle Even Though It's Sushi". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ (in Japanese) Osushiyasan no arukikata お寿司屋さんの歩き方 Archived 2012-02-29 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved February 2012.

- ^ (in Japanese) 'Ojisan, oaiso' tsuihō undō 「おじさん、おあいそ」追放運動 Archived 2012-05-09 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved February 2012.

- ^ "Japanese Meaning of 煮詰める, 煮つめる, につめる, nitsumeru". Nihongo Master. Archived from the original on February 4, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ Issenberg, Sasha. The Sushi Economy. Gotham Books: 2007

- ^ a b Honey, Kim (March 18, 2009). "Are you sushi savvy?". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on March 23, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ Lowry, Dave (2005). The Connoisseur's Guide to Sushi. Harvard Common Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-55832-307-0.

Further reading

[edit]- Mitshuhiro Araki, Chieko Asazuma (2004). 江戸前「握り」 (in Japanese). Kobunsha. ISBN 978-4334032319.

- Joro Ono, Masuhiro Yamamoto (2014). 鮨 すきやばし次郎: JIRO GASTRONOMY (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4093883856.

- Joro Ono, Masuhiro Yamamoto (2016). 匠 すきやばし次郎: JIRO PHILOSOPHY (in Japanese). Shogakukan. ISBN 978-4093884976.

External links

[edit]Sushi

View on GrokipediaHistory

Ancient Origins and Fermentation

The origins of sushi trace to Southeast Asia, particularly the Mekong River basin encompassing modern-day Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam, where the practice emerged as a method to preserve freshwater fish amid the region's wet-rice agriculture. In this ecosystem, flooded paddy fields teemed with fish during cultivation, creating seasonal surpluses that required long-term storage; lacto-fermentation using salt and rice enabled preservation for up to several months by harnessing anaerobic bacteria to produce lactic acid, inhibiting spoilage. While some sources, particularly certain Chinese references, attribute early forms to southern regions like Yunnan during the Eastern Han dynasty or coastal areas, mainstream historical consensus places the technique's roots in these Southeast Asian rice-fish ecosystems, with spread possibly northward to southern China before reaching Japan via cultural exchanges in the 8th-9th centuries.[7][8][9][10] This technique, predating the 2nd century CE in some accounts, involved packing cleaned fish with salted rice in barrels, allowing the rice to ferment and sour over time, which chemically preserved the fish through acidification rather than direct consumption of the rice. The process's causal tie to rice paddy systems is evident in historical patterns: rice cultivation's expansion facilitated fish trapping in irrigation networks, necessitating scalable preservation to sustain inland communities beyond immediate harvest. Early documentation appears in Chinese texts, such as the Qimin Yaoshu (544 CE), an agricultural compendium detailing fermentation-based food processing, including fish pastes akin to early preserved forms, underscoring the method's adaptation in adjacent rice-dependent societies.[11][12] By the 8th century, the practice migrated to Japan, likely introduced via Chinese cultural exchanges linked to Buddhism's spread, which emphasized vegetarianism but accommodated preserved fish products. In Japan, it manifested as narezushi, where the rice—fully fermented and inedible—was discarded after months or years, yielding pungent, sour fish as the edible outcome, distinct from later fresh preparations. Modern sushi forms, such as nigiri-zushi and rolls, represent Japanese innovations that evolved independently from this ancient preservation technique, emphasizing fresh seafood atop vinegared rice. Surviving regional variants, like funazushi from Lake Biwa carp, preserve this original fermentation ethos, with archaeological and textual evidence affirming its pre-Japanese roots without direct biomolecular confirmation of prehistoric sites.[13][14][15]Early Japanese Adaptations

In the Muromachi period (1336–1573), Japanese sushi began transitioning from the long-fermentation narezushi imported from Southeast Asia and China—where rice was discarded after months or years of preservation—to namanare-zushi, a semi-fresh adaptation with reduced fermentation times of days to weeks.[16][17] This shift allowed fish to be partially raw and wrapped in rice, which was consumed alongside the fish for a milder, less pungent flavor, rather than fully fermenting into a preserved product.[18][19] The practice reflected growing palatability preferences amid Japan's improving agricultural stability, reducing the necessity for extreme preservation methods once reliant on unreliable salt and rice fermentation.[20] By the 17th century, during the early Edo period, hayazushi emerged as a further refinement, eliminating extended fermentation entirely in favor of vinegar-seasoned rice mixed or paired with fresh or lightly cured fish, enabling consumption within hours or days.[21][22] This "fast sushi" mimicked the tangy acidity of fermentation through advancements in domestic vinegar production, such as sake lees-based methods, which provided a reliable souring agent without biological decay risks.[23] Urbanization and expanded trade in urban centers like Kyoto and Osaka drove demand for quicker-preparing foods, supported by higher-yield rice strains that ensured steadier supplies and lessened dependence on long-term storage.[24] Hayazushi thus marked a causal pivot toward flavor enhancement over mere preservation, laying groundwork for non-fermented rice's role in sushi while maintaining empirical ties to vinegar's preservative chemistry.[25]Edo Period Innovations