Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

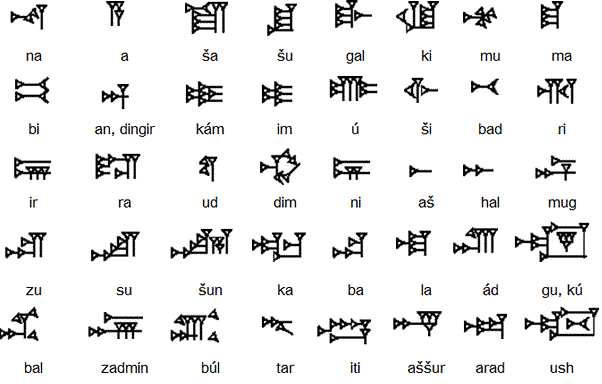

Syllabogram

View on WikipediaThis article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2024) |

Syllabograms are graphemes used to write the syllables or morae of words. Syllabograms in syllabaries are analogous to letters in alphabets, which represent individual phonemes, or logograms in logographies, which represent morphemes.

Syllabograms in the Maya script most frequently take the form of V (vowel) or CV (consonant-vowel) syllables of which approximately 83 are known. CVC signs are present as well. Two modern well-known examples of syllabaries consisting mostly of CV syllabograms are the Japanese kana, used to represent the same sounds in different occasions. Syllabograms tend not to be used for languages with more complicated syllables: for example English phonotactics allows syllables as complex as CCCVCCCC (as in /ˈstrɛŋkθs/ strengths), generating many thousands of possible syllables and making the use of syllabograms cumbersome.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Barker, Chris. "How many syllables does English have?". New York University. Archived from the original on 2016-08-22.