Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

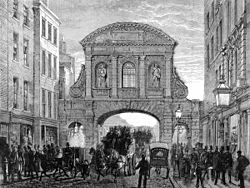

Temple Bar, London

View on Wikipedia

Temple Bar was the principal ceremonial entrance to the City of London from the City of Westminster. In the Middle Ages, London expanded city jurisdiction beyond its walls to gates, called 'bars', which were erected across thoroughfares. To the west of the City of London, the bar was located adjacent to the area known as the Temple. Temple Bar was situated on the historic royal ceremonial route from the Palace of the Tower of London to the old Palace of Westminster, the two chief residences of the medieval English monarchs, and from Westminster to St Paul's Cathedral. The road east of the bar within the city was Fleet Street, while the road to the west, in Westminster, was The Strand.

At the bar, the Corporation of the City of London erected a barrier to regulate trade into the city. The 19th century Royal Courts of Justice are located to its north, having been moved from Westminster Hall. To its south is Temple Church, along with the Inner Temple and Middle Temple Inns of Court. As the most important entrance to the City of London from Westminster, it was formerly long the custom for the monarch to halt at the Temple Bar before entering the City of London, in order for the Lord Mayor to offer the corporation's pearl-encrusted Sword of State as a token of loyalty.

'Temple Bar' strictly refers to a notional bar or barrier across the route near The Temple precinct, but it is also used to refer to the 17th-century ornamental, English Baroque arched gateway building attributed to Christopher Wren, which spanned the roadway at the bar for two centuries. After Wren's gateway was removed in 1878, the Temple Bar Memorial topped by a dragon symbol of London, and containing statues of Queen Victoria and Edward VII, was erected to mark the location. Wren's archway was preserved and was re-erected in 2004 within the City of London, in a redeveloped Paternoster Square next to St Paul's Cathedral. In September 2022, the preserved Wren gateway and an adjacent building were officially opened by the Duke of Gloucester as the home of the Worshipful Company of Chartered Architects.

Background

[edit]In the Middle Ages, the authority of the City of London Corporation reached beyond the city's ancient defensive walls in several places, known as the Liberties of London. To regulate trade into the city, barriers were erected on the major entrance routes wherever the true boundary was a substantial distance from the nearest ancient gatehouse in the walls. Temple Bar was the most used of these, since traffic between the City of London (England's prime commercial centre) and the Palace of Westminster (the political centre) passed through it. It was located where Fleet Street now meets The Strand, which is outside London's old boundary wall.[1]

Its name derives from the Temple Church, adjoining to the south, which has given its name to a wider area south of Fleet Street, the Temple, once belonging to the Knights Templar but now home to two of the legal profession's Inns of Court, and within the city's ancient boundaries.

The historic ceremony of the monarch halting at Temple Bar and being met by the Lord Mayor has often featured in art and literature. It is commented on in televised coverage of modern-day royal ceremonial processions.

History

[edit]

City jurisdiction and The Temple

[edit]A City bar at The Temple is first mentioned in 1293 and was probably only a chain or bar between a row of posts.[1] More substantial structures with arches followed. After the Battle of Evesham of 1265, Prince Edward punished the rebellious Londoners, who had befriended Simon de Montfort, by taking away all their street chains and bars, and storing them in the Tower of London.[2] By 1351, a timber archway had been built housing a small prison above it. The earliest known documentary and historical notice of Temple Bar is in 1327, concerning a hearing before the mayor regarding a right of way in the area. In 1384, Richard II granted a licence for paving the Strand Street from Temple Bar to the Savoy, and collecting tolls to cover the expense.

On 5 November 1422, the corpse of Henry V was borne to Westminster Abbey by the chief citizens and nobles, and every doorway from Southwark to Temple Bar had a torch-bearer. In 1503 the hearse of Elizabeth of York, queen of Henry VII, halted at Temple Bar, on its way from the Tower to Westminster, and at the Bar the Abbots of Westminster and Bermondsey blessed the corpse, and the Earl of Derby and a large company of nobles joined the funeral procession. Anne Boleyn passed through the Bar on 31 May 1534, the day before her coronation, on her way to the Tower. On that occasion Temple Bar was new painted and repaired, and near it stood singing men and children—the Fleet Street conduit all the time running claret.[2]

In 1554, Thomas Wyatt led an uprising in opposition to Queen Mary I's proposed marriage to Philip II of Spain. When he had fought his way down Piccadilly to The Strand, Temple Bar was thrown open to him, or forced open by him; but when he had been repulsed at Ludgate he was hemmed in by cavalry at Temple Bar, where he surrendered. This revolt persuaded the government to go through with the execution of Lady Jane Grey.[2]

The notable Scottish bookseller Andrew Millar owned his first London shop at Temple Bar, taken over from the ownership of James McEuen in 1728, to whom Millar had been apprenticed.[3]

Wren's Temple Bar Gate

[edit]

Although the then existing Bar Gate at the Temple escaped damage by the Great Fire of London of 1666, it was decided to rebuild it as part of the general improvement works made throughout the city after that devastating event. Commissioned by King Charles II, and attributed to Sir Christopher Wren, the fine arch of Portland stone was constructed between 1669 and 1672, by Thomas Knight, the City Mason, and Joshua Marshall, Master of the Mason's Company and King's Master Mason, while John Bushnell carved the statues.[4]

Rusticated, it is a two-story structure consisting of one wide central arch for the road traffic, flanked on both sides by narrower arches for pedestrians. On the upper part, four statues celebrate the 1660 Restoration of the Stuart monarchy: in its original setting, on the west side King Charles II is shown with his father King Charles I whose parents King James I and Anne of Denmark are depicted on the east side.[5] During the 18th century the heads of convicted traitors were frequently mounted on pikes and exhibited on the roof, as was the case on London Bridge. The other seven principal gateways to London, (Ludgate, Newgate, Aldersgate, Cripplegate, Moorgate, Bishopsgate and Aldgate) were all demolished in the 1760s, but Temple Bar remained despite its impediment to the ever-growing traffic. The upper-storey room was leased to the neighbouring banking house of Child & Co for storage of records.[2]

In the 1853 novel, Bleak House, Charles Dickens described it as "that leaden-headed old obstruction, appropriate ornament for the threshold of a leaden-headed old corporation" (the City of London corporation). It was also the subject of jokes, "Why is Temple Bar like a lady's veil? Both must be raised (razed) for "busses" ('buses). It was noted in jest "as a weak spot in our defences", since one could walk through the adjoining barbershop where one door opened on to the city and the other in the area of Westminster.

In 1874 it was discovered that the keystones had dropped and the arches were propped up with timbers. The steady increase in horse and cart traffic led to complaints that Temple Bar was becoming a bottleneck, holding back the City trade. In 1878 the City of London Corporation, eager to widen the road but unwilling to destroy so historic a monument, dismantled it piece-by-piece over an 11-day period and stored its 2,700 stones carefully. In 1880 the brewer Henry Meux, at the instigation of his wife Valerie Susan Meux, bought the stones and re-erected the arch as the facade of a new gatehouse in the park of his mansion house Theobalds Park in Hertfordshire, the site of a former substantial prodigy house of James VI and I.[6] There it remained, positioned in a woodland clearing, until 2003. A plaque now marks the Hertfordshire site.

-

Artist's conception of the Temple Bar Gate at the commencement of the 18th century. Note heads on pikes above the gate.

-

Temple Bar by Philip Norman, 1876

-

Temple Bar Gate required timber support props in the 1870s and was dismantled in 1878.

-

Temple Bar Gate was re-erected at Theobalds Park in Hertfordshire in the late 19th century. Pictured here in 1968, it stood there until being moved back to London.

-

Temple Bar Gate at Theobalds Park, 1999

The Gate's present location

[edit]

In March 1938 Theobalds Park was sold by Sir Hedworth Meux to Middlesex County Council, but Wren's Temple Bar Gatehouse was excluded from the sale and retained by the Meux trustees in the park.[7] In 1984 it was bought by the Temple Bar Trust from the Meux Trust for the sum of £1. In December 2001 the city's Court of Common Council resolved to contribute funds for the return of Temple Bar Gate to the city.[8] On 13 October 2003 the first stone was dismantled at Theobalds Park[9] and all were placed on 500 pallets for storage. In 2004 it was returned to the City of London where it was painstakingly re-erected as an entrance to the Paternoster Square redevelopment immediately north of St Paul's Cathedral, opening to the public on 10 November 2004. The total cost of the project was over £3 million, funded mainly by the City of London, with donations from the Temple Bar Trust and several City Livery Companies.

In September 2022, Temple Bar London, consisting of the gateway and an adjacent building (Paternoster Lodge),[10] was officially reopened by the Duke of Gloucester and the Lord Mayor of London Vincent Keaveny as the home of a livery company, the Worshipful Company of Chartered Architects, providing space for meetings and dining and an education centre funded by the Corporation of London's CIL Neighbourhood fund.[citation needed]

The top of one of the gates was offered for sale by Dreweatts Auctioneers in a London sale of surplus stock from LASSCO on 15 June 2013.[11]

Temple Bar Memorial

[edit]Some authorities believe that the griffin which adorns Temple Bar is a copy of the Welsh dragon. It is Said to be Curiously like it.

Following the removal of Wren's gate, Horace Jones, Architect and Surveyor to the City of London, designed a memorial to mark Temple Bar, which was unveiled in 1880. The Temple Bar Memorial stands in the street in front of the Royal Courts of Justice.

The elaborate pedestal in a neo-Renaissance style serves as the base for a sculpture by Charles Bell Birch of a dragon supporter (sometimes erroneously referred to as a griffin) bearing a shield of the arms of the City of London. The pedestal is decorated with statues by Joseph Boehm of Queen Victoria and her son the then Prince of Wales, the last royals to have entered the City through Wren's gate, which event is depicted in one of the reliefs which also decorate the structure.[13][full citation needed]

-

Temple Bar Memorial in 2009 (installed 1880)

-

South face, Queen Victoria

-

South face, Queen Victoria's Progress to the Guildhall, 1837

-

North face, Edward VII, when he was Prince of Wales

-

North face, Queen Victoria and the Prince (Edward VII) and Princess of Wales going to St Paul's, 1872

-

East face with St Clement Danes in the background.

-

Head (west) end of the dragon

-

The dragon from the south

In the 1960s, similar but smaller and more subdued dragon sculptures were set at other entry points to the city. Two were originally created in 1849 by J. B. Bunning for the entrance to the Coal Exchange (and were relocated to Victoria Embankment following that building's demolition in 1962), while the others are smaller-scale versions of Bunning's design.

In fiction

[edit]

Charles Dickens mentioned Temple Bar in A Tale of Two Cities (Book II, Chapter I), noting its proximity to the fictional Tellson's Bank on Fleet Street. This was in fact Child & Co., which used the upper rooms of Temple Bar as storage space. Whilst critiquing the moral poverty of late 18th-century London, Dickens wrote that in matters of crime and punishment, "putting to death was a recipe much in vogue", and illustrated the horror caused by severed heads "exposed on Temple Bar with an insensate brutality and ferocity".[14]

In Herman Melville's The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids, he contrasts the beauty of the Temple Bar gateway at the highest point on the road leading to the hellish paper factory, which he calls a "Dantean Gateway" (in his Inferno, Dante describes the gateway to Hell, over which are written the words, "Abandon all hope, ye who enter here").[15]

The dragon on top of the Temple Bar monument comes to life in Charlie Fletcher's children's book about London, Stoneheart.[16]

The dragon also features in Virginia Woolf's The Years, in which one of the main characters, Martin, points "at the splayed-out figure at Temple Bar; it looked as ridiculous as usual – something between a serpent and a fowl."[17]

See also

[edit]- Dragon boundary mark

- Temple Bar, Dublin, a district of the same name in Dublin, Ireland

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b ""Temple Bar", City of London". Archived from the original on 30 March 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d Thornbury, Walter. "Temple Bar", Old and New London, Vol. 1. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878. pp.22-31 British History Online. Web. 21 July 2015

- ^ "The manuscripts, Letter from Allan Ramsay to Andrew Millar, 20 May, 1735. Andrew Millar Project. University of Edinburgh". millar-project.ed.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ Robinson, John. "Decline and Fall of a Monument: Temple Bar", History Today Vol. 31, Issue 10, October 1981

- ^ "Christopher Wren's Temple Bar". victorianweb.org. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Historic England. "Temple Bar (1393844)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "Theobalds Park – Temple Bar Gateway". thetemplebar.info. April 2009. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ "Temple Bar Gateway". thetemplebar.info. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ "First stone is dismantled – Temple Bar Gateway". thetemplebar.info. 13 October 2003. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ "About Temple Bar: Background". Temple Bar Trust. 17 January 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Dreweatts". Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Yorkshire Evening Post, Tuesday 1 March 1898

- ^ Details and photos at Victorian Web.

- ^ "Glossary". Discovering Dickens. No. 3. Stanford University. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Melville, Herman (1855). "Paradise of Bachelors and Tartarus of Maids" (PDF). Harper's Magazine.

- ^ "The Stones of London: Public Art in Charlie Fletcher's Stoneheart Trilogy". The Literary London Journal. 1 September 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ Woolf, Virginia (1937). The Collected Novels of Virginia Woolf – The Years, The Waves. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 9781473363113.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

External links

[edit]Temple Bar, London

View on GrokipediaOverview and Location

Definition and Significance

Temple Bar serves as the westernmost historic gateway to the City of London, originally established as a simple chain or bar across the road in medieval times to regulate entry and trade from the west, which later evolved into a more substantial stone archway structure.[5][3] This barrier, first recorded around 1293, marked the jurisdictional edge of the City's liberties and was rebuilt in the late 17th century following the Great Fire of 1666.[1][4] The site embodies a dual identity, referring not only to the physical gate but also to the surrounding Temple Bar district, a key legal enclave in London that includes the historic precincts of the Inner and Middle Temples, two of the four principal Inns of Court central to barrister training and the English legal profession since the 14th century.[6][1] This area, originally associated with the Knights Templar, has long been a hub for legal societies and remains integral to the administration of justice in England and Wales.[6] Symbolically, Temple Bar represents the historic boundary between the City of London and the adjacent City of Westminster, delineating shifts in governance and authority while serving as the ceremonial principal entrance for royal processions, where monarchs traditionally pause to request permission from the Lord Mayor to enter the City.[4][1] As the last surviving gateway among the City's original eight principal entrances, it holds enduring iconic status for its ties to London's legal heritage and civic pageantry, despite its relocation in the 19th century to accommodate urban development.[1][4]Geographical Position

Temple Bar originally occupied the junction where Fleet Street meets the Strand in central London, marking a historic gateway into the City.[1] Its exact position is commemorated by the Temple Bar Memorial at coordinates 51°30′49″N 0°06′43″W.[7] This site formed the principal western boundary between the City of London and the City of Westminster, separating the jurisdictions of the two historic entities.[8] Specifically, it delineates the western edge of the City wards of Farringdon Without to the north and Castle Baynard to the south along Fleet Street.[5] The location lies in immediate proximity to several key landmarks, including the Royal Courts of Justice, built on the site after the gate's 19th-century removal; St Clement Danes church, situated just west along the Strand; and the Thames Embankment, approximately 300 meters to the south.[1] Topographically, Temple Bar was positioned on gently rising ground ascending from the valley of the Fleet River, which once flowed openly into the Thames nearby but has been culverted and buried underground since the 18th century, contributing to its strategic role as a controlled entry to the City.Historical Background

Medieval Origins and City Jurisdiction

The origins of Temple Bar trace back to the late 13th century, when London's westward expansion necessitated clear markers for the City's jurisdictional boundaries beyond its ancient walls. The first recorded mention of the bar appears in 1293, describing it as a simple chain or pole stretched across the road near the Temple area.[2] This rudimentary barrier reflected the growing commercial importance of the route connecting the City of London to Westminster, serving as one of several "bars" that extended civic authority over suburban liberties without enclosing the entire metropolis.[3] By the early 14th century, amid ongoing urban growth and increasing traffic, the basic chain evolved into a more substantial timber archway, completed by 1351, which included a small prison above the gate for detaining offenders.[3] This structure underscored Temple Bar's role as a key demarcation between the City's liberties and the jurisdiction of Westminster, often sparking disputes over control and rights of way. These tensions highlighted how the bar functioned not merely as a physical obstacle but as a symbol of London's self-governance during its medieval expansion. A pivotal event came during the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, when rebels under Wat Tyler forced their way into the City by throwing down the gate on 13 June, breaching the barrier despite efforts to block entry and defend the western approach.[9] Following the uprising, the structure was rebuilt and further integrated into the City's defensive framework, reinforcing its position as the principal western gateway and a linchpin of jurisdictional integrity.[2] This episode cemented Temple Bar's enduring role in London's medieval administrative and protective landscape.The Role of The Temple

The Temple area in London traces its origins to the 12th century, when it formed part of the Knights Templar's precinct in the city, granted by King Henry II in 1160 to serve as their English headquarters after relocating from earlier accommodations in Holborn.[10][11] The order, founded in 1119 to protect Christian pilgrims in the Holy Land, established a fortified compound here that included administrative, military, and religious functions, reflecting their dual role as warrior-monks and early international bankers.[12] This grant positioned the Temple as a significant ecclesiastical and strategic outpost, adjacent to the Thames and within the expanding boundaries of medieval London. Central to the Templars' presence was the construction of the Temple Church, begun in the 1160s and consecrated on February 10, 1185, by Heraclius, Patriarch of Jerusalem, in the presence of King Henry II.[10] Modeled on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, the round nave symbolized the order's crusading origins and served as a place of worship, chapter house, and repository for royal treasures during the reigns of Henry II and King John.[13] The church's enduring ecclesiastical role influenced the surrounding area's development, fostering a blend of spiritual and institutional activities that later intertwined with emerging legal traditions. The dissolution of the Knights Templar in 1312, ordered by Pope Clement V at the Council of Vienne amid charges of heresy, led to the transfer of their properties—including the Temple—to the Knights Hospitaller, another military religious order, via the papal bull Ad providam issued in May 1312.[14] The Hospitallers, lacking immediate need for the London site, began leasing portions of the Temple lands to groups of lawyers and law students by 1346, marking the inception of organized legal societies in the area.[6] These leases provided affordable housing and communal spaces for apprentices training in the common law, laying the foundational stones for what would become the Inns of Court and transforming the Templars' former precinct into a burgeoning hub for legal education and practice.[15] The Temple Church retained its ecclesiastical prominence amid this shift, becoming closely associated with the legal communities that occupied the adjacent lands; it hosted ceremonies such as the admission of new barristers and annual commemorative services for the Inns, integrating spiritual rituals into professional legal life. This adjacency reinforced the area's dual identity as both an ecclesiastical sanctuary and a center for legal training, where the church's historical sanctity lent prestige to the evolving institutions. A pivotal formalization occurred in 1608, when King James I issued letters patent dividing the Temple into two distinct societies: the Honourable Society of the Inner Temple and the Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, granting them perpetual tenure of their respective estates along the Thames.[16] This division, building on earlier informal separations dating back to the 14th century, entrenched the legal character of the precinct by establishing autonomous governance structures for each Inn, ensuring their role in calling students to the Bar and perpetuating the Templars' legacy as the cradle of English legal professionalism.[17]The Temple Bar Gate

Design and Construction by Christopher Wren

Following the Great Fire of London in 1666, which destroyed much of the city's medieval structures, Temple Bar was commissioned in 1669 by King Charles II as part of the broader reconstruction efforts overseen by the City Corporation.[4] The project was attributed to Sir Christopher Wren, the renowned architect appointed as Surveyor of the King's Works in 1669, who directed the rebuilding of numerous City landmarks including St. Paul's Cathedral.[1] Construction began shortly thereafter and was completed in 1672, executed primarily by the City Mason, Thomas Knightley, to replace the earlier timber-framed gate that had been deemed inadequate.[2] The structure was built from Portland stone quarried in Dorset, a durable limestone favored by Wren for its resistance to London's polluted atmosphere and its ability to take fine detailing.[2] Measuring approximately 21 meters wide and 18 meters high, it featured a single central archway for carriages flanked by narrower pedestrian passages, topped by two octagonal turrets that served both decorative and functional purposes, such as housing lanterns.[1] The overall form drew from Baroque principles, with Wren incorporating elements inspired by Roman triumphal arches like the Arch of Constantine, evident in the rusticated quoins, pedimented niches, and layered entablatures that emphasized grandeur and symmetry.[2] Key decorative elements included four life-sized statues carved by John Bushnell, positioned in niches on the facade: on the eastern (City) side, representations of James I and his queen, Anne of Denmark; on the western (Westminster) side, Charles I and Charles II.[1] These figures, which accounted for about one-third of the total budget, symbolized the continuity of monarchical authority and the City's allegiance.[2] The total cost of construction was approximately £1,500, funded through City rates levied on coal imports, reflecting Wren's efficient approach to post-fire public works.[2] One notable innovation was the inclusion of a concealed upper chamber above the arch, accessible via a narrow staircase within one of the turrets, intended for use by City officials during ceremonial processions or as a vantage point for oversight.[1] This room, barrel-vaulted and lead-roofed, measured roughly 4 by 6 meters and exemplified Wren's practical integration of utility into monumental design, though it saw limited original use beyond occasional gatherings.[2]Ceremonial and Symbolic Functions

The Temple Bar gate functioned as the primary ceremonial portal into the City of London from Westminster, where monarchs traditionally halted to seek formal permission from the Lord Mayor before proceeding, a ritual underscoring the City's historic independence. This custom dated back centuries and persisted through the 18th and early 19th centuries, with the sovereign's coach pausing at the gate amid civic pageantry. For instance, in 1689, following his accession, William III participated in such a ceremonial entry, where City officials greeted the new king and returned the symbolic sword of state at the gate. Similarly, on November 9, 1837, Queen Victoria's state coach stopped at Temple Bar during her inaugural visit to the City, where she was received by the Lord Mayor and aldermen in a display of mutual respect between crown and corporation.[18][19] The gate also anchored annual civic celebrations, notably the Lord Mayor's Show, where newly elected mayors led elaborate processions through its arches, accompanied by livery companies, musicians, and floats to affirm the City's commercial vitality and traditions. These events, held since medieval times but prominent in the 18th and 19th centuries, transformed Temple Bar into a stage for communal spectacle, drawing crowds to witness the pomp and reinforcing bonds between the City's guilds and residents.[20][21] Symbolically, Temple Bar embodied the boundary between the royal domain of Westminster and the self-governing City, serving as a potent emblem of civic authority and jurisdictional sovereignty that demanded deference even from the monarch. From the late 17th century onward, its apex spikes bore the severed heads of executed traitors as a grim deterrent against sedition, a practice that intensified after major rebellions to publicly enforce loyalty. Notable among these were the heads of Jacobite rebels following the 1745 uprising, including Colonel Francis Townley and others from the Manchester Regiment, which were displayed with the last heads removed shortly after 1746, serving as a stark warning to potential dissidents entering the City.[2][22][19] In everyday operations from the late 17th to mid-19th centuries, the gate enforced practical controls, including the collection of tolls from non-freemen and vehicles passing through, a revenue stream that supported City maintenance until the practice was phased out around the mid-1850s amid growing traffic demands. Watchmen stationed there monitored passage, collected these fees, and maintained vigilance against unauthorized entry, ensuring the gate's role as both a fiscal and security checkpoint.[21][23] Erected by Christopher Wren in the 1670s in the wake of the Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of 1666, Temple Bar stood as an enduring symbol of London's fortitude and rebirth, its Portland stone archway heralding the reconstructed City's defiance and enduring prosperity. The structure's statues of monarchs like Charles I and Charles II further evoked continuity and royal patronage, while the gate's prominence in processions and displays projected civic pride to visitors and reinforced the boundaries of London's commercial heart.[2][19]19th-Century Removal and Relocation

By the 1870s, Temple Bar had become a significant impediment to traffic flow along Fleet Street, exacerbated by the growing volume of vehicles and pedestrians entering the City of London, while structural cracks in the stonework indicated decay.[4] Additionally, plans for the construction of the Royal Courts of Justice necessitated road widening in the area.[24] The City of London Corporation decided to dismantle the gateway, a process that began on January 2, 1878, when the first stone was removed; the work was meticulously executed brick by brick and beam by beam, with each of the approximately 2,500 stones numbered for potential reassembly, and completed just 11 days later on January 13.[24][4] The disassembled pieces were initially stored in a yard off Farringdon Road, where they remained scattered for nearly a decade amid uncertainty about their future.[24] In 1887, the stones were purchased from the City Corporation by Sir Henry Bruce Meux, a wealthy brewer, at the behest of his wife, Lady Valerie Meux, who sought to acquire the historic structure to enhance the entrance to their estate at Theobalds Park in Hertfordshire.[4] The acquisition and subsequent relocation cost over £10,000, covering transportation of the 400 tons of material by horse-drawn low flat trolleys and the reconstruction efforts.[4] Re-erected as a folly and grand gateway to the estate, the gate was officially completed in 1888 with modifications including a new lodge adjoining the structure, buttresses for stability, and an internal staircase providing access to the upper chamber, where Lady Meux hosted notable guests.[4][2] The rebuilt Temple Bar was formally opened in 1889, transforming it from a urban relic into a picturesque feature of the rural landscape.[2] Following Lady Meux's death in 1910, the gate eventually passed to other owners, and with the sale of the estate in 1938 (excluding the gate), it fell into neglect, suffering rapid deterioration from exposure to the elements, including erosion of the stonework and collapse of parts of the roof.[4] Over the subsequent decades, it endured further damage from vandalism, such as graffiti on the surfaces, and general disrepair, leaving it in a dilapidated state by the mid-20th century despite its earlier designation as a Scheduled Ancient Monument in 1930.[25][26] Temple Bar remained at Theobalds Park for over a century, a testament to its relocation amid Victorian urban expansion, until efforts in the late 20th century addressed its preservation.[4]Restoration and Return to the City

In 1984, the Temple Bar Trust acquired the gate from the Meux Trust for a nominal sum of £1, with the intention of eventually returning it to the City of London.[27] The full restoration project, spanning 2001 to 2004, was funded primarily by the Corporation of the City of London at a cost of approximately £3 million, supplemented by donations from the Temple Bar Trust and various Livery Companies.[28] This effort involved meticulous conservation work by specialist contractors, retaining 95% of the original stonework while performing extensive stone cleaning to remove centuries of grime and structural reinforcement to ensure long-term stability.[28] The reconstructed gate was reinstalled in Paternoster Square, immediately north of St Paul's Cathedral, as part of the area's redevelopment, and officially opened to the public on 10 November 2004 by the Lord Mayor of London, Alderman Robert Finch.[2][29] Today, the gate serves as a pedestrian entrance to Paternoster Square and is open to the public for educational events, including talks and guided tours focused on the history of the City of London and its architecture.[30] It also hosts occasional exhibitions on related historical themes and provides space for meetings and community gatherings, all managed by the Temple Bar Trust with ongoing annual maintenance to preserve its condition.[30][1] As of 2025, the gate remains integrated into official City of London walking tours, offering visitors contextual insights into its ceremonial past without significant structural changes since its 2004 reinstallation.[1]The Temple Bar District

Development of the Inns of Court

Following the suppression of the Knights Templar in 1312, the Crown assumed control of the Temple estate and began leasing portions to lawyers who had informally occupied the site since the early 14th century for professional lodging and instruction. By the mid-14th century, these lawyers had coalesced into organized societies within the Inner and Middle Temple, utilizing the Templars' existing halls for communal activities. The societies are first distinctly named in a 1388 manuscript yearbook, marking their recognition as separate entities, with the Middle Temple's administrative records commencing in 1501 and the Inner Temple's in 1505, signifying the formal inception of their institutional frameworks.[31][32][33] The Inns functioned as autonomous, self-regulating associations dedicated to barrister education, governed by senior members known as Masters of the Bench, who managed admissions, ethical standards, and professional calls to the Bar. Training emphasized practical skills through mandatory dinners for socialization and knowledge exchange, moots for argumentative practice, and formal readings—lectures on statutes delivered by elected readers—held in the Inns' halls. In 1608, King James I issued a royal charter jointly to the Inner and Middle Temple, granting them perpetual tenure of the Temple lands free from external interference and affirming their role as the preeminent centers for common law instruction.[34][15][6] The 16th century witnessed substantial growth amid the Tudor expansion of the legal profession, with the Inns acquiring additional lands following the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s, which freed up properties for repurchase and development. The Middle Temple, under Treasurer Edmund Plowden, erected a grand new hall from 1562 to 1574, featuring a hammerbeam roof crafted from Windsor oak, while the Inner Temple rebuilt Hare Court by 1567 and added over 100 sets of chambers to house its burgeoning student body of around 151 residents by 1574. These developments reinforced the Inns' status as a "third university" for the gentry, blending legal pedagogy with broader liberal arts until the late 17th century, when readings gradually declined.[35][36][6] The Great Fire of London in 1666 inflicted severe damage on the Inner Temple, gutting its hall and much of its western structures, though rapid demolition efforts spared the Middle Temple from total devastation. Reconstruction proceeded swiftly under the 1667 Rebuilding Act, mandating brick and stone materials; the Inner Temple's halls and walks were restored by the 1680s, exemplifying resilient adaptation. Further calamity struck during the World War II Blitz, when incendiary bombs razed the Inner Temple's hall, library, and church roof in 1940–1941, while the Middle Temple lost over one-third of its 285 chamber sets and saw its gardens and hall heavily scarred. Postwar renewal, funded partly by government compensation exceeding £1.4 million for the Inner Temple alone, rebuilt the sites through the 1950s, including the Inner Temple Hall's completion in 1955 and the Middle Temple's Queen Elizabeth Building in 1958, preserving historical facades amid modern necessities.[37][38][39] By the 19th century, criticisms of the Inns' informal training methods prompted reforms via a 1854 Royal Commission, which investigated legal education at the Inns of Court and Chancery, leading to mandatory examinations, structured curricula, and the 1877 Judicature Act's integration of bar calls with university degrees, thereby modernizing barrister preparation while upholding the Inns' governance autonomy.[40]Architectural and Cultural Landmarks

The Temple Church, a central architectural landmark in the district, features a distinctive round nave constructed in the 12th century and consecrated in 1185 by Patriarch Heraclius of Jerusalem, designed to evoke the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.[10] The nave, one of only four surviving round churches in England, exemplifies early Gothic elements with its Purbeck marble columns and ribbed vaulting.[41] Adjoining it is the rectangular chancel, added in 1240 in the Early English Gothic style, featuring lancet windows and a vaulted ceiling to accommodate increased liturgical needs.[42] The church houses nine 13th- and 14th-century stone effigies of knights, including that of William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke (d. 1219), who served as regent and oversaw the reissue of Magna Carta in 1217, symbolizing the site's ties to medieval legal history. Prominent among the Inn halls is Middle Temple Hall, constructed between 1562 and 1574 under Treasurer Edmund Plowden, featuring a double hammerbeam timber roof considered one of the finest Elizabethan examples in London for its intricate carvings and structural elegance.[35] The hall's oak-paneled interior and stained-glass windows further highlight its Renaissance craftsmanship, serving as a venue for legal dining and performances since its completion. Adjacent, the Inner Temple Library, established by the mid-16th century with records dating to at least 1540, holds one of England's oldest collections of legal texts, including rare manuscripts and early printed works on common law, housed in a 19th-century building that preserves its historical significance.[43] Other notable structures include King's Bench Walk, a row of barristers' chambers rebuilt in 1678 following a fire, constructed in red brick with classical pediments and doorways attributed to Sir Christopher Wren, reflecting post-Fire restoration aesthetics in the district.[44] Nearby, the Strand Lane Baths, remnants of a 17th-century cistern originally built in 1612 for Somerset House but long reputed as Roman remains since the 1830s, now function as a public museum showcasing preserved stonework and arches, offering insight into early modern water engineering.[45] The district's cultural landscape is enriched by serene gardens, such as those of the Inner and Middle Temples, featuring wrought-iron gates, manicured lawns, and wooden benches that provide contemplative spaces amid the legal precincts. Scattered plaques and memorials honor influential figures, including Sir William Blackstone (1723–1780), a Middle Temple barrister whose Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765–1769) systematized common law.[46]Modern Commercial and Social Life

The Temple Bar district remains a central hub for the legal profession in London, primarily due to its location within the historic Inns of Court, which house thousands of barristers across Inner Temple and Middle Temple. These institutions support a vibrant community of practicing barristers, with sets such as Outer Temple Chambers and Temple Garden Chambers actively engaging in commercial and dispute resolution work, contributing to the area's status as a key center for legal practice. The district frequently hosts events organized by the Law Society and international legal bodies, including the Four Jurisdictions Law Conference at Middle Temple, which brings together barristers from England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland to discuss cross-jurisdictional issues.[47][48] Commercially, the area blends its legal heritage with a range of hospitality and retail options, particularly along the Strand. Historic pubs like The Devereux, established in 1677 as the Grecian Coffee House and later refurbished as a pub in the 19th century, serve as popular gathering spots for legal professionals and visitors, offering traditional British fare in a setting tied to figures such as Isaac Newton. Complementing these are boutique shops and cafes, including the iconic Twinings Tea Shop at 216 Strand, the oldest tea shop in London with over 300 years of history, and modern coffee houses like WatchHouse and Roasting Plant Coffee, which provide specialty brews in architecturally rich surroundings.[49][50][51][52] Social and tourist activities thrive in the district, with regular guided walks exploring its legal and architectural heritage, such as the Temple Bar Trust's "Portal to the City's Story" tours and daily walks organized by the City of London Guides, attracting visitors year-round. The area participates in broader cultural events like the Open House Festival, where the Inns of Court open their grounds for public access in September, fostering community engagement through talks and exhibitions. Post-COVID recovery has seen a shift toward hybrid formats for legal events, with seminars and conferences at venues like Garden Court Chambers incorporating virtual elements to accommodate remote participation while maintaining in-person networking.[53][54][55][56] In 2025, recent developments emphasize sustainability and adaptation to digital trends within the legal sector. The Inns of Court have advanced environmental initiatives through networks like Achill Legal, which assists barristers' chambers in measuring and reducing emissions, with sets such as Serjeants' Inn implementing ongoing programs for net-zero practices. Amid rising remote work trends, where UK law firms report employees averaging 3.2 office days per week, the district has seen growth in digital-focused practices, exemplified by Outer Temple Chambers' expertise in fintech and blockchain law, enabling hybrid operations that blend traditional advocacy with virtual client services.[57][58][59][60]Memorials and Legacy

The Temple Bar Memorial

The Temple Bar Memorial was erected in 1880 by Sir Horace Jones, the Architect and Surveyor to the City of London, to mark the site of the former Temple Bar gate following its removal in 1878 due to increasing traffic congestion.[61][62] The monument serves as a boundary marker delineating the historic divide between the City of London and the City of Westminster, while also functioning as a pedestrian refuge to facilitate safer crossing at the busy junction of Fleet Street and the Strand.[63][64] Constructed primarily from granite, the memorial features a pedestal of red Aberdeen granite with blue Guernsey granite at the base and Shap granite spur stones to protect against vehicle impact.[62] It includes niches housing Sicilian marble statues of Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) by Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm, along with bronze relief panels depicting royal processions by sculptors Samuel Joseph Kelsey and Charles Henry Mabey.[62][65] Atop the structure sits a bronze dragon—often misidentified as a griffin—crafted by Charles Bell Birch, symbolizing the City of London and echoing the dragon boundary markers found at other City perimeters.[66] The frieze bears the inscription "TEMPLE BAR" to commemorate the gate's original location.[67] Designated a Grade II listed structure on 5 February 1970 for its architectural and historical significance, the memorial remains a prominent traffic island amid the junction's flow.[61] As of 2025, it continues to aid pedestrian navigation in this high-traffic area, serving as a focal point for photographs and occasional City of London ceremonial events.[68][1]Representations in Culture and Media

Temple Bar has long served as a symbolic boundary in British literature, embodying the transition from Westminster to the City of London and evoking themes of history, ceremony, and urban grit. In Charles Dickens' Barnaby Rudge (1841), the gateway appears as a key landmark in the novel's depiction of 18th-century London unrest, with descriptions of creaking shop signs eastward of Temple Bar and its role as a revered constitutional entry point approached with solemnity.[69] Similarly, Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories utilize the foggy, historic ambiance of the Temple district near Temple Bar as a backdrop for intrigue, notably in "A Scandal in Bohemia" (1891), where Irene Adler's association with the Inner Temple underscores the area's legal and shadowy undertones.[70] In visual art, Temple Bar's imposing presence captured the imagination of 18th- and 19th-century artists, often highlighting its ceremonial and macabre aspects. William Hogarth's engraving Burning the Rumps at Temple Bar (1726), the eleventh plate in his Hudibras series, satirically portrays a riotous crowd burning effigies of political figures at the gate, critiquing Restoration-era politics through exaggerated chaos.[71] By the 19th century, prints frequently focused on the gateway's grim tradition of displaying traitors' heads on iron spikes, as in the 19th-century lithograph depicting the severed heads of rebels Francis Townley and George Fletcher atop the arch in 1746, serving as a stark warning to passersby.[72] Temple Bar's enduring symbolism extends to film, television, and modern media, where it represents London's layered past and boundary-defining role. Though not a primary filming location in major series like BBC's Sherlock (2010–2017), the gateway's vicinity in the Temple area informs the show's evocation of Victorian fog-shrouded streets.[73] In contemporary digital media, Temple Bar is integrated into video games like Assassin's Creed Syndicate (2015), where players navigate the Victorian Temple district, including landmarks near the original site, to explore London's underbelly.[74] Tourism applications, including the official Visit London app, highlight the gateway as a must-see relic, offering augmented reality tours of its history and proximity to St. Paul's Cathedral.[75] These representations reinforce Temple Bar's resonance as a threshold between eras and jurisdictions, occasionally invoked in discussions of modern boundaries, though its ceremonial echoes from royal processions persist in symbolic contexts.References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_heads_of_Townley_and_Fletcher_exposed_on_Temple_Bar,_August_2nd_1746.jpg