Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Texas Towers

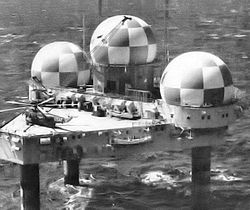

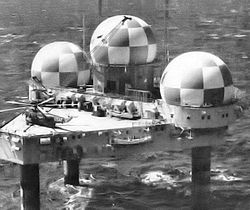

View on WikipediaTexas Towers were a set of three radar facilities off the eastern seaboard of the United States which were used for surveillance by the United States Air Force during the Cold War. Modeled on the offshore oil drilling platforms first employed off the Texas coast, they were in operation from 1958 to 1963. After the collapse of one of the towers in 1961, the remaining towers were closed due to changes in threat perception and out of a concern for the safety of the crews.

Key Information

Planning

[edit]Upon re-formation of the Air Defense Command in 1951 to oversee the nation's developing surveillance radar network, there was concern that shore-based radars along the east coast provided insufficient warning time. A 1952 report from MIT's Lincoln Laboratory looked into the possibility of extending radar coverage by building platforms in the Atlantic using offshore oil drilling technology.[1] They concluded that a set of such platforms, equipped with radars, could extend coverage several hundred miles offshore, giving half an hour additional warning of an attack.[2] Funding for design and construction of the towers was approved in January 1954.[1]

Design

[edit]

Each tower consisted of a triangular platform, 200 feet (61 m) on each side, standing on three caisson legs.[3][4] The structures were constructed on land, towed to site, and jacked up to clear the sea surface by 67 feet (20 m).[3] Radar and other equipment were then installed on location. The platform itself contained two floors housing the living areas; two of the legs held fuel oil for diesel generators, while the third held the intake for the desalination unit. The platform roof served as a helicopter landing area. A rotary gantry was suspended from the platform to allow servicing of its underside.

Each platform was equipped with one AN/FPS-3 (later upgraded to AN/FPS-20) search radar and two AN/FPS-6 height finder radars, each housed in a separate spherical neoprene radome 55 feet (17 m) in diameter.[4] Originally the towers were to be linked to shore by submarine cable, but this was eventually rejected as too costly; the AN/FRC-56 tropospheric scatter microwave link was installed instead, with an array of three parabolic antennas attached to one edge of the platform.[2] UHF and VHF equipment allowed communication with ships and aircraft as well as providing a backup to the microwave link.

Installations

[edit]Five towers were planned, in an array off the New England/mid-Atlantic coast. The most northerly two proposed were dropped from plans due to budgetary constraints.[2]

Logistical support for all three towers was provided by the 4604th Support Squadron, based out of Otis AFB and specifically constituted for this mission.[2] They were originally equipped with H-21B helicopters,[2] which were replaced with three Sikorsky SH-3 helicopters acquired in 1962.[5] The USNS New Bedford was used to supply the stations, with transfer being effected with a platform called the "donut", consisting of an inflated rubber ring surmounted by a railing, which was lowered from the platform to the waiting ship's deck. These transfers could take place only at slack tide, when the ship could maintain position.[6]

| Tower ID | Location | Staffing unit | Mainland station | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT-1 | Cashes Ledge off New Hampshire coast 42°53′N 68°57′W / 42.883°N 68.950°W |

Not built | ||

| TT-2 | Georges Bank off Cape Cod 41°45′0.00″N 67°46′0.00″W / 41.7500000°N 67.7666667°W |

762d Radar Squadron | North Truro Air Force Station | decommissioned 1963 |

| TT-3 | Nantucket Shoals 40°45′00.00″N 69°19′0.00″W / 40.7500000°N 69.3166667°W |

773d Radar Squadron | Montauk AFS | decommissioned 1963 |

| TT-4 | off Long Beach Island, New Jersey 39°48′N 72°40′W / 39.800°N 72.667°W |

646th Radar Squadron | Highlands Air Force Station | collapsed (1961) |

| TT-5 | Browns Bank south of Nova Scotia 42°47′N 65°37′W / 42.783°N 65.617°W |

Not built |

Operational history

[edit]Texas Tower 2 was the first to become operational, starting limited service in May 1956.[7] It became fully operational in 1958, as did Tower 3; Tower 4 followed in April 1959.[8] The original plan to integrate these radars into the SAGE system had to be modified when the direct cable connection was eliminated; instead, they were used to provide manual inputs.

All the towers were noisy and prone to vibration from the equipment. The relative flexibility of the supports also caused them to shake and sway in response to wind and waves.[6] The frequent and sustained sounding of the platform's foghorns was also an annoyance to the crew.[2]

Texas Tower 4

[edit]

Tower 4 was plagued with structural problems from the start. It stood in much deeper water than the other two - 185 feet (56 m), compared to 80 feet (24 m) for Tower 2 - and it was held that the simple cylindrical leg design would not be sturdy enough given the length of the legs. Therefore, three sets of cross braces were added between the legs, attached with pin joints.[2][9] These made it impossible to tow the platform on the level; instead, the structure was laid on its side for transport and then tipped upright at the site.[9] These braces proved to be frail and the joints prone to loosening: two braces broke loose during transport, and a third was lost when the tower was being placed on the bottom.[10] Divers were brought in several times to inspect the structure and to perform repairs, and an additional set of crossbraces was installed immediately below the platform, above the waterline, in 1960.[11] Crewmen were frequently seasick from the swaying, and Tower 4 was nicknamed "Old Shaky".[2]

On September 12, 1960, Hurricane Donna passed over Tower 4, causing severe structural damage, including the loss of the flying bridge hanging beneath the platform, and one of the communications dishes.[12] After assessment of the damage and initial repairs it was decided to reduce staffing to a skeleton crew and prepare to dismantle the station.[12] The site could not simply be abandoned for fear that the Soviets would board it and remove sensitive equipment and documentation.[12] Dismantling of the tower was therefore protracted. At the approach of another storm in January 1961, evacuation of the station was impeded by the inability of the commander to make contact with any of his three immediate superiors; nonetheless the New Bedford set out for the platform.[13] As the storm built, USS Wasp, which was in the vicinity, was also dispatched with the intent of evacuating the station via helicopter, shore aircraft being unable to take off.[13] Both ships reached the vicinity but could do no more than watch the station disappear from their radar. No survivors were recovered, though divers were sent down on the chance that some might have been trapped in the wreckage.[13] Twenty-eight airmen and civilian contractors perished.[14] Only two bodies were recovered.[14]

Texas Tower 5

[edit]| Texas Tower 5 | |

|---|---|

| Part of Aerospace Defense Command | |

| Site information | |

| Type | Long Range Radar Site |

| Owner | U.S. Air Force |

| Location | |

| |

| Coordinates | 42°47′N 65°37′W / 42.783°N 65.617°W |

| Site history | |

| Built by | U.S. Government |

Texas Tower 5 was planned to be built on Brown's Bank, 35 nautical miles (65 km; 40 mi) south of the coast of Nova Scotia in 84 feet (26 m) of water.[15] The 4604th Support Group was supposed to be located at Pease Air Force Base, New Hampshire. The USAF approved the construction of Tower #5 on January 11, 1954, but the tower was never built because of improvements to radar over the area.

Closure

[edit]The loss of Tower 4, together with the increasing emphasis on ICBMs as the predominant threat, led a reassessment of the remaining towers. Escape capsules were added to the two remaining towers, allowing rapid evacuation.[2][4] Shortly thereafter it was decided to close the remaining towers, and the electronic equipment was removed. Both platforms were expected to be returned to shore for scrap, but Tower 2 sank and could not be recovered. Tower 3 was then filled with foam before being knocked off its support, and it was successfully returned to shore and dismantled. The wreckage of Towers 2 and 4 remains in place on the ocean floor. Radar coverage was taken over by alterations to EC-121 airborne early warning flights based out of Otis Air Force Base.[2]

- Patches of tower units

-

Tower 2 patch

-

Tower 3 patch

-

4604th Support Squadron patch

See also

[edit]- PAVE PAWS

- Radar picket

- Sea-based X-band Radar

- SAGE

- Other Cold War era radar networks:

References

[edit]- ^ a b Keeney, L. Douglas (2011). 15 Minutes: General Curtis LeMay and the Countdown to Nuclear Annihilation. Macmillan. p. 100.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ray, Thomas W. "A History of Texas Towers in Air Defense 1952-1964". Texas Tower Association. Archived from the original on 2010-07-15. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- ^ a b Howe, Hartley E. (October 1955). "Radar Island Rises 110 Miles at Sea". Popular Science: 126–129, 268. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- ^ a b c Kaufmann, J. E.; Kaufmann, H. W. (2004). Fortress America: The forts that defended America, 1600 to the present. Da Capo Press. pp. 371–372. ISBN 978-0-306-81294-1. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- ^ "Rotary Wing Aircraft". Flying: 117. November 1962. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- ^ a b Wylie, Evan McLeod (July 26, 1963). "Farewell to the Iron Bastards: Texas Towers Await the Wreckers". Life. pp. 7, 9. Retrieved 2012-01-22.

- ^ Leonard, Barry, ed. (2011). History of Strategic and Ballistic Missile Defense: Volume II: 1956-1972. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 9781437921311. p. 305

- ^ Leonard, p. 312

- ^ a b Keeney, pp. 150-152

- ^ Keeney, p. 190

- ^ Keeney, pp. 226-228

- ^ a b c Keeney, pp.229-232

- ^ a b c Keeney, pp.262-275

- ^ a b Southall, Ashley, "Obama Recognizes Men Who Died in the Collapse of a Radar Tower in 1961", New York Times, 9 February 2011; retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ "The Texas Towers: Proposed". The Texas Towers.Com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

External links

[edit]- The short film Georges Bank Radar Station (1957) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- The Texas Towers Association website via archive.org

- http://www.radomes.org/museum/documents/TexasTower.html More information about the Texas Towers from http://www.radomes.org.

- United States Senate Committee on Armed Services (1961). Inquiry into the Collapse of Texas Tower No. 4. United States Government Printing Office.

- Analysis on the collapse of Texas Tower 4