Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Oil platform

View on Wikipedia

An oil platform, also called an oil rig, offshore platform, or oil production platform, is a large structure with facilities to extract and process petroleum and natural gas that lie in rock formations beneath the seabed. Many oil platforms will also have facilities to accommodate the workers, although it is also common to have a separate accommodation platform linked by bridge to the production platform. Most commonly, oil platforms engage in activities on the continental shelf, though they can also be used in lakes, inshore waters, and inland seas. Depending on the circumstances, the platform may be fixed to the ocean floor, consist of an artificial island, or float.[1] In some arrangements the main facility may have storage facilities for the processed oil. Remote subsea wells may also be connected to a platform by flow lines and by umbilical connections. These sub-sea facilities may include one or more subsea wells or manifold centres for multiple wells.

Offshore drilling presents environmental challenges, both from the produced hydrocarbons and the materials used during the drilling operation. Controversies include the ongoing US offshore drilling debate.[2]

There are many different types of facilities from which offshore drilling operations take place. These include bottom-founded drilling rigs (jackup barges and swamp barges), combined drilling and production facilities, either bottom-founded or floating platforms, and deepwater mobile offshore drilling units (MODU), including semi-submersibles and drillships. These are capable of operating in water depths up to 3,000 metres (9,800 ft). In shallower waters, the mobile units are anchored to the seabed. However, in deeper water (more than 1,500 metres (4,900 ft)), the semisubmersibles or drillships are maintained at the required drilling location using dynamic positioning.

History

[edit]Jan Józef Ignacy Łukasiewicz[3] (Polish pronunciation: [iɡˈnatsɨ wukaˈɕɛvitʂ]; 8 March 1822 – 7 January 1882) was a Polish pharmacist, engineer, businessman, inventor, and philanthropist. He was one of the most prominent philanthropists in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, crown land of Austria-Hungary. He was a pioneer who in 1856 built the world's first modern oil refinery.

Around 1891, the first submerged oil wells were drilled from platforms built on piles in the fresh waters of the Grand Lake St. Marys (a.k.a. Mercer County Reservoir) in Ohio. The wide but shallow reservoir was built from 1837 to 1845 to provide water to the Miami and Erie Canal.

Around 1896, the first submerged oil wells in salt water were drilled in the portion of the Summerland field extending under the Santa Barbara Channel in California. The wells were drilled from piers extending from land out into the channel.

Other notable early submerged drilling activities occurred on the Canadian side of Lake Erie since 1913 and Caddo Lake in Louisiana in the 1910s. Shortly thereafter, wells were drilled in tidal zones along the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana. The Goose Creek field near Baytown, Texas, is one such example. In the 1920s, drilling was done from concrete platforms in Lake Maracaibo, Venezuela.

The oldest offshore well recorded in Infield's offshore database is the Bibi Eibat well which came on stream in 1923 in Azerbaijan.[4] Landfill was used to raise shallow portions of the Caspian Sea.

In the early 1930s, the Texas Company developed the first mobile steel barges for drilling in the brackish coastal areas of the gulf.

In 1937, Pure Oil Company (now Chevron Corporation) and its partner Superior Oil Company (now part of ExxonMobil Corporation) used a fixed platform to develop a field in 14 feet (4.3 m) of water, one mile (1.6 km) offshore of Calcasieu Parish, Louisiana.

In 1938, Humble Oil built a mile-long wooden trestle with railway tracks into the sea at McFadden Beach on the Gulf of Mexico, placing a derrick at its end – this was later destroyed by a hurricane.[5]

In 1945, concern for American control of its offshore oil reserves caused President Harry Truman to issue an Executive Order unilaterally extending American territory to the edge of its continental shelf, an act that effectively ended the 3-mile limit "freedom of the seas" regime.

In 1946, Magnolia Petroleum (now ExxonMobil) drilled at a site 18 miles (29 km) off the coast, erecting a platform in 18 feet (5.5 m) of water off St. Mary Parish, Louisiana.

In early 1947, Superior Oil erected a drilling/production platform in 20 ft (6.1 m) of water some 18 miles[vague] off Vermilion Parish, Louisiana. But it was Kerr-McGee Oil Industries (now part of Occidental Petroleum), as operator for partners Phillips Petroleum (ConocoPhillips) and Stanolind Oil & Gas (BP), that completed its historic Ship Shoal Block 32 well in October 1947, months before Superior actually drilled a discovery from their Vermilion platform farther offshore. In any case, that made Kerr-McGee's well the first oil discovery drilled out of sight of land.[6][7]

The British Maunsell Forts constructed during World War II are considered the direct predecessors of modern offshore platforms. Having been pre-constructed in a very short time, they were then floated to their location and placed on the shallow bottom of the Thames and the Mersey estuary.[7][8]

In 1954, the first jackup oil rig was ordered by Zapata Oil. It was designed by R. G. LeTourneau and featured three electro-mechanically operated lattice-type legs. Built on the shores of the Mississippi River by the LeTourneau Company, it was launched in December 1955, and christened "Scorpion". The Scorpion was put into operation in May 1956 off Port Aransas, Texas. It was lost in 1969.[9][10][11]

When offshore drilling moved into deeper waters of up to 30 metres (98 ft), fixed platform rigs were built, until demands for drilling equipment was needed in the 30 metres (98 ft) to 120 metres (390 ft) depth of the Gulf of Mexico, the first jack-up rigs began appearing from specialized offshore drilling contractors such as forerunners of ENSCO International.

The first semi-submersible resulted from an unexpected observation in 1961. Blue Water Drilling Company owned and operated the four-column submersible Blue Water Rig No.1 in the Gulf of Mexico for Shell Oil Company. As the pontoons were not sufficiently buoyant to support the weight of the rig and its consumables, it was towed between locations at a draught midway between the top of the pontoons and the underside of the deck. It was noticed that the motions at this draught were very small, and Blue Water Drilling and Shell jointly decided to try operating the rig in its floating mode. The concept of an anchored, stable floating deep-sea platform had been designed and tested back in the 1920s by Edward Robert Armstrong for the purpose of operating aircraft with an invention known as the "seadrome". The first purpose-built drilling semi-submersible Ocean Driller was launched in 1963. Since then, many semi-submersibles have been purpose-designed for the drilling industry mobile offshore fleet.

The first offshore drillship was the CUSS 1 developed for the Mohole project to drill into the Earth's crust.

As of June, 2010, there were over 620 mobile offshore drilling rigs (Jackups, semisubs, drillships, barges) available for service in the competitive rig fleet.[12]

One of the world's deepest hubs is currently the Perdido in the Gulf of Mexico, floating in 2,438 meters of water. It is operated by Shell plc and was built at a cost of $3 billion.[13] The deepest operational platform is the Petrobras America Cascade FPSO in the Walker Ridge 249 field in 2,600 meters of water.

Main offshore basins

[edit]

Notable offshore basins include:

- the North Sea

- the Gulf of Mexico (offshore Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida)

- California (in the Los Angeles Basin and Santa Barbara Channel, part of the Ventura Basin)

- the Caspian Sea (notably some major fields offshore Azerbaijan)

- the Campos and Santos Basins off the coasts of Brazil

- Newfoundland and Nova Scotia (Atlantic Canada)

- several fields off West Africa, south of Nigeria, and central Africa, west of Angola

- offshore fields in South East Asia and Sakhalin, Russia

- major offshore oil fields are located in the Persian Gulf such as Safaniya, Manifa and Marjan which belong to Saudi Arabia and are developed by Saudi Aramco[14]

- fields in India (Mumbai High, K G Basin-East Coast Of India, Tapti Field, Gujarat, India)

- the Baltic Sea oil and gas fields

- the Taranaki Basin in New Zealand

- the Kara Sea north of Siberia[15]

- the Arctic Ocean off the coasts of Alaska and Canada's Northwest Territories[16]

- the offshore fields in the Adriatic Sea

Types

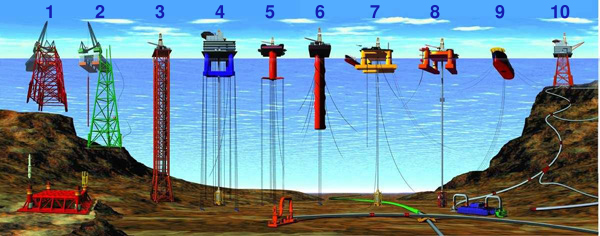

[edit]Larger lake- and sea-based offshore platforms and drilling rig for oil.

- 1) & 2) Conventional fixed platforms

- 3) Compliant tower

- 4) & 5) Vertically moored tension leg and mini-tension leg platform

- 6) Spar

- 7) & 8) Semi-submersibles

- 9) Floating production, storage, and offloading facility

- 10) Sub-sea completion and tie-back to host facility

Note that jack-up drilling rigs, drillships, and gravity-based structures are not pictured here.

Fixed platforms

[edit]

These platforms are built on concrete or steel legs, or both, anchored directly onto the seabed, supporting the deck with space for drilling rigs, production facilities and crew quarters. Such platforms are, by virtue of their immobility, designed for very long term use (for instance the Hibernia platform). Various types of structures are used: steel jacket, concrete caisson, floating steel, and even floating concrete. Steel jackets are structural sections made of tubular steel members, and are usually piled into the seabed. To see more details regarding design, construction and installation of such platforms refer to:[18] and.[19]

Concrete caisson structures, pioneered by the Condeep concept, often have in-built oil storage in tanks below the sea surface. These tanks were often used as a flotation capability, allowing them to be built close to shore (Norwegian fjords and Scottish firths are popular because they are sheltered and deep enough) and then floated to their final position where they are sunk to the seabed. Fixed platforms are economically feasible for installation in water depths up to about 520 m (1,710 ft).

Compliant towers

[edit]These platforms consist of slender, flexible towers and a pile foundation supporting a conventional deck for drilling and production operations. Compliant towers are designed to sustain significant lateral deflections and forces, and are typically used in water depths ranging from 370 to 910 metres (1,210 to 2,990 ft).

Tension-leg platform

[edit]TLPs are floating platforms tethered to the seabed in a manner that eliminates most vertical movement of the structure. TLPs are used in water depths up to about 2,000 meters (6,600 feet). The "conventional" TLP is a 4-column design that looks similar to a semisubmersible. Proprietary versions include the Seastar and MOSES mini TLPs; they are relatively low cost, used in water depths between 180 and 1,300 metres (590 and 4,270 ft). Mini TLPs can also be used as utility, satellite or early production platforms for larger deepwater discoveries.

Spar platforms

[edit]

Spars are moored to the seabed like TLPs, but whereas a TLP has vertical tension tethers, a spar has more conventional mooring lines. Spars have to-date been designed in three configurations: the "conventional" one-piece cylindrical hull; the "truss spar", in which the midsection is composed of truss elements connecting the upper buoyant hull (called a hard tank) with the bottom soft tank containing permanent ballast; and the "cell spar", which is built from multiple vertical cylinders. The spar has more inherent stability than a TLP since it has a large counterweight at the bottom and does not depend on the mooring to hold it upright. It also has the ability, by adjusting the mooring line tensions (using chain-jacks attached to the mooring lines), to move horizontally and to position itself over wells at some distance from the main platform location. The first production spar[when?] was Kerr-McGee's Neptune, anchored in 590 m (1,940 ft) in the Gulf of Mexico; however, spars (such as Brent Spar) were previously used[when?] as FSOs.

Eni's Devil's Tower located in 1,710 m (5,610 ft) of water in the Gulf of Mexico, was the world's deepest spar until 2010. The world's deepest platform as of 2011 was the Perdido spar in the Gulf of Mexico, floating in 2,438 metres of water. It is operated by Royal Dutch Shell and was built at a cost of $3 billion.[13][20][21]

The first truss spars[when?] were Kerr-McGee's Boomvang and Nansen.[citation needed] The first (and, as of 2010, only) cell spar[when?] is Kerr-McGee's Red Hawk.[22]

Semi-submersible platform

[edit]These platforms have hulls (columns and pontoons) of sufficient buoyancy to cause the structure to float, but of weight sufficient to keep the structure upright. Semi-submersible platforms can be moved from place to place and can be ballasted up or down by altering the amount of flooding in buoyancy tanks. They are generally anchored by combinations of chain, wire rope or polyester rope, or both, during drilling and/or production operations, though they can also be kept in place by the use of dynamic positioning. Semi-submersibles can be used in water depths from 60 to 6,000 metres (200 to 20,000 ft).

Floating production systems

[edit]

The main types of floating production systems are FPSO (floating production, storage, and offloading system). FPSOs consist of large monohull structures, generally (but not always) shipshaped, equipped with processing facilities. These platforms are moored to a location for extended periods, and do not actually drill for oil or gas. Some variants of these applications, called FSO (floating storage and offloading system) or FSU (floating storage unit), are used exclusively for storage purposes, and host very little process equipment. This is one of the best sources for having floating production.

The world's first floating liquefied natural gas (FLNG) facility is in production. See the section on particularly large examples below.

Jack-up drilling rigs

[edit]

Jack-up Mobile Drilling Units (or jack-ups), as the name suggests, are rigs that can be jacked up above the sea using legs that can be lowered, much like jacks. These MODUs (Mobile Offshore Drilling Units) are typically used in water depths up to 120 metres (390 ft), although some designs can go to 170 m (560 ft) depth. They are designed to move from place to place, and then anchor themselves by deploying their legs to the ocean bottom using a rack and pinion gear system on each leg.

Drillships

[edit]A drillship is a maritime vessel that has been fitted with drilling apparatus. It is most often used for exploratory drilling of new oil or gas wells in deep water but can also be used for scientific drilling. Early versions were built on a modified tanker hull, but purpose-built designs are used today. Most drillships are outfitted with a dynamic positioning system to maintain position over the well. They can drill in water depths up to 3,700 m (12,100 ft).[23]

Gravity-based structure

[edit]A GBS can either be steel or concrete and is usually anchored directly onto the seabed. Steel GBS are predominantly used when there is no or limited availability of crane barges to install a conventional fixed offshore platform, for example in the Caspian Sea. There are several steel GBS's in the world today (e.g. offshore Turkmenistan Waters (Caspian Sea) and offshore New Zealand). Steel GBS do not usually provide hydrocarbon storage capability. It is mainly installed by pulling it off the yard, by either wet-tow or/and dry-tow, and self-installing by controlled ballasting of the compartments with sea water. To position the GBS during installation, the GBS may be connected to either a transportation barge or any other barge (provided it is large enough to support the GBS) using strand jacks. The jacks shall be released gradually whilst the GBS is ballasted to ensure that the GBS does not sway too much from target location.

Normally unmanned installations (NUI)

[edit]These installations, sometimes called toadstools, are small platforms, consisting of little more than a well bay, helipad and emergency shelter. They are designed to be operated remotely under normal conditions, only to be visited occasionally for routine maintenance or well work.

Conductor support systems

[edit]These installations, also known as satellite platforms, are small unmanned platforms consisting of little more than a well bay and a small process plant. They are designed to operate in conjunction with a static production platform which is connected to the platform by flow lines or by umbilical cable, or both.

Particularly large examples

[edit]

Deepest platforms by type

[edit]This is a list of oil wells based on the depth of the water in which they were drilled. It doesn't include how deep underground they go, which in some cases is over 10,000 metres.

| Category | Platform | Country | Location | Height (meters) | Height (feet) | Year built | Coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spar | Perdido | Gulf of Mexico | 2,934 | 9,627 | 2011 | 26°7′44″N 94°53′53″W / 26.12889°N 94.89806°W | |

| Floating production storage and offloading facility | Turritella[24] | Gulf of Mexico | 2,900 | 9,514 | 2016 | ||

| Semi-submersible | Independence Hub | Gulf of Mexico | 2,438 | 8,000 | 2007 | ||

| Extended Tension-leg platform | Big Foot | Gulf of Mexico | 1,580 | 5,180 | 2018 | ||

| Compliant tower | Petronius | Gulf of Mexico | 640 | 2,100 | 2000 | 29°06′30″N 87°56′30″W / 29.10833°N 87.94167°W | |

| Fixed platform | Bullwinkle | Gulf of Mexico | 529 | 1,736 | 1988 | 27°53′01″N 90°54′04″W / 27.88361°N 90.90111°W | |

| Gravity-based structure | Troll A | North Sea | 472 | 1,549 | 1996 | 60°40′N 3°40′E / 60.667°N 3.667°E |

Other deep compliant towers and fixed platforms, by water depth:

- Baldpate Platform, 502 m (1,647 ft)

- Pompano Platform, 393 m (1,289 ft)

- Benguela-Belize Lobito-Tomboco Platform, 390 m (1,280 ft)

- Gullfaks C Platform, 380 m (1,250 ft)

- Tombua Landana Platform, 366 m (1,201 ft)

- Harmony Platform, 366 m (1,201 ft)

Other metrics

[edit]The Hibernia platform in Canada is the world's heaviest offshore platform, located on the Jeanne d'Arc Basin, in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Newfoundland. This gravity base structure (GBS), which sits on the ocean floor, is 111 metres (364 ft) high and has storage capacity for 1.3 million barrels (210,000 m3) of crude oil in its 85-metre (279 ft) high caisson. The platform acts as a small concrete island with serrated outer edges designed to withstand the impact of an iceberg. The GBS contains production storage tanks and the remainder of the void space is filled with ballast with the entire structure weighing in at 1.2 million tons.

Royal Dutch Shell has developed the first Floating Liquefied Natural Gas (FLNG) facility, which is situated approximately 200 km off the coast of Western Australia. It is the largest floating offshore facility. It is approximately 488m long and 74m wide with displacement of around 600,000t when fully ballasted. [25]

History of deepest offshore oil wells

[edit]This is a list of oil wells based on the depth of the water in which they were drilled. It doesn't include how deep underground they go, which in some cases is over 10,000 metres.

| Record from | Record held (years) | Name and location | Height (metres) | Height (feet) | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 4 | MC-198 offshore oil well | 674 | 2,211 | [26] |

| 1984 | 2 | MC-852 offshore oil well | 1,077 | 3,534 | [26] |

| 1986 | 1 | MC-731 offshore oil well | 1,646 | 5,400 | [26] |

| 1987 | 1 | AT-471 offshore oil well | 2,071 | 6,794 | [26] |

| 1988 | 6 | MC-657 offshore oil well | 2,292 | 7,520 | [26] |

| 1996 | 2 | AC-600 offshore oil well | 2,323 | 7,620 | [26] |

| 1998 | 2 | AT-118 offshore oil well | 2,352 | 7,716 | [26] |

| 2000 | 1 | WR-425 offshore oil well | 2,696 | 8,845 | [26] |

| 2001 | 2 | AC-903 oil well, offshore United States | 2,965 | 9,727 | [26] |

| 2003 | 5 | AC-951 oil well, offshore United States | 3,051 | 10,011 | [26] |

| 2008 | 3 | LL 511 #1 (G10496) oil well, offshore United States | 3,091 | 10,141 | [27] |

| 2011 | 2 | CYPR-D7-A1 oil well, offshore India | 3,107 | 10,194 | [27] |

| 2013 | 0 | NA7-1 oil well, offshore India | 3,165 | 10,384 | [27] |

| 2013 | 3 | 1-D-1 oil well, offshore India | 3,174 | 10,413 | [27][28] |

| 2016 | 4 | Raya-1 oil well, offshore Uruguay | 3,400 | 11,155 | [28][29] |

| 2021 | TBD | Ondjaba 1 oil well, offshore Angola | 3,628 | 11,903 | [29][30] |

Maintenance and supply

[edit]

A typical oil production platform is self-sufficient in energy and water needs, housing electrical generation, water desalinators and all of the equipment necessary to process oil and gas such that it can be either delivered directly onshore by pipeline or to a floating platform or tanker loading facility, or both. Elements in the oil/gas production process include wellhead, production manifold, production separator, glycol process to dry gas, gas compressors, water injection pumps, oil/gas export metering and main oil line pumps.

Larger platforms are assisted by smaller ESVs (emergency support vessels) like the British Iolair that are summoned when something has gone wrong, e.g. when a search and rescue operation is required. During normal operations, PSVs (platform supply vessels) keep the platforms provisioned and supplied, and AHTS vessels can also supply them, as well as tow them to location and serve as standby rescue and firefighting vessels.

Crew

[edit]Essential personnel

[edit]Not all of the following personnel are present on every platform. On smaller platforms, one worker can perform a number of different jobs. The following also are not names officially recognized in the industry:

- OIM (offshore installation manager) who is the ultimate authority during their shift and makes the essential decisions regarding the operation of the platform;

- Operations Team Leader (OTL);

- Offshore Methods Engineer (OME) who defines the installation methodology of the platform;

- Offshore Operations Engineer (OOE) who is the senior technical authority on the platform;

- PSTL or operations coordinator for managing crew changes;

- Dynamic positioning operator, navigation, ship or vessel maneuvering (MODU), station keeping, fire and gas systems operations in the event of incident;

- Automation systems specialist, to configure, maintain and troubleshoot the process control systems (PCS), process safety systems, emergency support systems and vessel management systems;

- Second mate to meet manning requirements of flag state, operates fast rescue craft, cargo operations, fire team leader;

- Third mate to meet manning requirements of flag state, operate fast rescue craft, cargo operations, fire team leader;

- Ballast control operator to operate fire and gas systems;

- Crane operators to operate the cranes for lifting cargo around the platform and between boats;

- Scaffolders to rig up scaffolding for when it is required for workers to work at height;

- Coxswains to maintain the lifeboats and manning them if necessary;

- Control room operators, especially FPSO or production platforms;

- Catering crew, including people tasked with performing essential functions such as cooking, laundry and cleaning the accommodation;

- Production techs to run the production plant;

- Helicopter pilot(s) living on some platforms that have a helicopter based offshore and transporting workers to other platforms or to shore on crew changes;

- Maintenance technicians (instrument, electrical or mechanical).

- Fully qualified medic.

- Radio operator to operate all radio communications.

- Store Keeper, keeping the inventory well supplied

- Technician to record the fluid levels in tanks

Incidental personnel

[edit]Drill crew will be on board if the installation is performing drilling operations. A drill crew will normally comprise:

- Toolpusher

- Driller

- Roughnecks

- Roustabouts

- Company man

- Mud engineer

- Motorman See: Glossary of oilfield jargon

- Derrickhand

- Geologist

- Welders and Welder Helpers

Well services crew will be on board for well work. The crew will normally comprise:

- Well services supervisor

- Wireline or coiled tubing operators

- Pump operator

- Pump hanger and ranger

Drawbacks

[edit]Risks

[edit]

The nature of their operation—extraction of volatile substances sometimes under extreme pressure in a hostile environment—means risk; accidents and tragedies occur regularly. The U.S. Minerals Management Service reported 69 offshore deaths, 1,349 injuries, and 858 fires and explosions on offshore rigs in the Gulf of Mexico from 2001 to 2010.[31] On July 6, 1988, 167 people died when Occidental Petroleum's Piper Alpha offshore production platform, on the Piper field in the UK sector of the North Sea, exploded after a gas leak. The resulting investigation conducted by Lord Cullen and publicized in the first Cullen Report was highly critical of a number of areas, including, but not limited to, management within the company, the design of the structure, and the Permit to Work System. The report was commissioned in 1988, and was delivered in November 1990.[32] The accident greatly accelerated the practice of providing living accommodations on separate platforms, away from those used for extraction.

The offshore can be in itself a hazardous environment. In March 1980, the 'flotel' (floating hotel) platform Alexander L. Kielland capsized in a storm in the North Sea with the loss of 123 lives.[33]

In 2001, Petrobras 36 in Brazil exploded and sank five days later, killing 11 people.

Given the number of grievances and conspiracy theories that involve the oil business, and the importance of gas/oil platforms to the economy, platforms in the United States are believed to be potential terrorist targets.[34] Agencies and military units responsible for maritime counter-terrorism in the US (Coast Guard, Navy SEALs, Marine Recon) often train for platform raids.[35]

On April 21, 2010, the Deepwater Horizon platform, 52 miles off-shore of Venice, Louisiana, (property of Transocean and leased to BP) exploded, killing 11 people, and sank two days later. The resulting undersea gusher, conservatively estimated to exceed 20 million US gallons (76,000 m3) as of early June 2010, became the worst oil spill in US history, eclipsing the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

Ecological effects

[edit]

In British waters, the cost of removing all platform rig structures entirely was estimated in 2013 at £30 billion.[36]

Aquatic organisms invariably attach themselves to the undersea portions of oil platforms, turning them into artificial reefs. In the Gulf of Mexico and offshore California, the waters around oil platforms are popular destinations for sports and commercial fishermen, because of the greater numbers of fish near the platforms. The United States and Brunei have active Rigs-to-Reefs programs, in which former oil platforms are left in the sea, either in place or towed to new locations, as permanent artificial reefs. In the US Gulf of Mexico, as of September 2012, 420 former oil platforms, about 10 percent of decommissioned platforms, have been converted to permanent reefs.[37]

On the US Pacific coast, marine biologist Milton Love has proposed that oil platforms off California be retained as artificial reefs, instead of being dismantled (at great cost), because he has found them to be havens for many of the species of fish which are otherwise declining in the region, in the course of 11 years of research.[38][39] Love is funded mainly by government agencies, but also in small part by the California Artificial Reef Enhancement Program. Divers have been used to assess the fish populations surrounding the platforms.[40]

Effects on the environment

[edit]

Offshore oil production involves environmental risks, most notably oil spills from oil tankers or pipelines transporting oil from the platform to onshore facilities, and from leaks and accidents on the platform.[41] Produced water is also generated, which is water brought to the surface along with the oil and gas; it is usually highly saline and may include dissolved or unseparated hydrocarbons.

Offshore rigs are shut down during hurricanes.[42] In the Gulf of Mexico the number hurricanes is increasing because of the increasing number of oil platforms that heat surrounding air with methane. It is estimated that oil and gas facilities in the Gulf of Mexico emit approximately 500000 tons of methane each year, corresponding to a 2.9% loss of produced gas. The increasing number of oil rigs also increases the number and movement of oil tankers, resulting in increasing CO2 levels which directly warm water in the zone. Warm waters are a key factor for hurricanes to form.[43]

To reduce the amount of carbon emissions otherwise released into the atmosphere, methane pyrolysis of natural gas pumped up by oil platforms is a possible alternative to flaring for consideration. Methane pyrolysis produces non-polluting hydrogen in high volume from this natural gas at low cost. This process operates at around 1000 °C and removes carbon in a solid form from the methane, producing hydrogen.[44][45][46] The carbon can then be pumped underground and is not released into the atmosphere. It is being evaluated in such research laboratories as Karlsruhe Liquid-metal Laboratory (KALLA).[47] and the chemical engineering team at University of California – Santa Barbara[48]

Repurposing

[edit]If not decommissioned,[49] old platforms can be repurposed to pump CO2 into rocks below the seabed.[50][51] Others have been converted to launch rockets into space, and more are being redesigned for use with heavy-lift launch vehicles.[52]

In Saudi Arabia, there are plans to repurpose decommissioned oil rigs into a theme park.[53]

Challenges

[edit]Offshore oil and gas production is more challenging than land-based installations due to the remote and harsher environment. Much of the innovation in the offshore petroleum sector concerns overcoming these challenges, including the need to provide very large production facilities. Production and drilling facilities may be very large and a large investment, such as the Troll A platform standing on a depth of 300 meters.

Another type of offshore platform may float with a mooring system to maintain it on location. While a floating system may be lower cost in deeper waters than a fixed platform, the dynamic nature of the platforms introduces many challenges for the drilling and production facilities.

The ocean can add several thousand meters or more to the fluid column. The addition increases the equivalent circulating density and downhole pressures in drilling wells, as well as the energy needed to lift produced fluids for separation on the platform.

The trend today is to conduct more of the production operations subsea, by separating water from oil and re-injecting it rather than pumping it up to a platform, or by flowing to onshore, with no installations visible above the sea. Subsea installations help to exploit resources at progressively deeper waters—locations that had been inaccessible—and overcome challenges posed by sea ice such as in the Barents Sea. One such challenge in shallower environments is seabed gouging by drifting ice features (means of protecting offshore installations against ice action includes burial in the seabed).

Offshore manned facilities also present logistics and human resources challenges. An offshore oil platform is a small community in itself with cafeteria, sleeping quarters, management and other support functions. In the North Sea, staff members are transported by helicopter for a two-week shift. They usually receive higher salaries than onshore workers do. Supplies and waste are transported by ship, and the supply deliveries need to be carefully planned because storage space on the platform is limited. Today, much effort goes into relocating as many of the personnel as possible onshore, where management and technical experts are in touch with the platform by video conferencing. An onshore job is also more attractive for the aging workforce in the petroleum industry, at least in the western world. These efforts among others are contained in the established term integrated operations. The increased use of subsea facilities helps achieve the objective of keeping more workers onshore. Subsea facilities are also easier to expand, with new separators or different modules for different oil types, and are not limited by the fixed floor space of an above-water installation.

See also

[edit]- List of tallest oil platforms

- Accommodation platform

- Chukchi Cap

- Deep sea mining

- Deepwater drilling

- Drillship

- North Sea oil

- Offshore geotechnical engineering

- Offshore oil and gas in the United States

- Oil drilling

- Protocol for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Fixed Platforms Located on the Continental Shelf

- SAR201

- Shallow water drilling

- Submarine pipeline

- TEMPSC

- Texas Towers

References

[edit]- ^ Ronalds, BF (2005). "Applicability ranges for offshore oil and gas production facilities". Marine Structures. 18 (3): 251–263. Bibcode:2005MaStr..18..251R. doi:10.1016/j.marstruc.2005.06.001.

- ^ Compton, Glenn, "10 Reasons Not to Drill for Oil Offshore of Florida Archived 2020-08-05 at the Wayback Machine", The Bradenton Times, Sunday, January 14, 2018

- ^ "Ignacy Łukasiewicz: Generous Inventor of the Kerosene Lamp".

- ^ "Oil in Azerbaijan". Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ Morton, Michael Quentin (June 2016). "Beyond Sight of Land: A History of Oil Exploration in the Gulf of Mexico". GeoExpro. 30 (3): 60–63. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Ref accessed 02-12-89 by technical aspects and coast mapping. Kerr-McGee

- ^ a b "Project Redsand CIO | Protecting The Redsand Towers". Archived from the original on 2017-07-02. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ^ Mir-Yusif Mir-Babayev (Summer 2003). "Azerbaijan's Oil History: Brief Oil Chronology since 1920 Part 2". Azerbaijan International. Vol. 11, no. 2. pp. 56–63. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- ^ "Rowan Companies marks 50th anniversary of landmark LeTourneau jackup" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-31. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- ^ "History of offshore drilling units – PetroWiki". petrowiki.org. 2 June 2015. Archived from the original on 2017-03-22. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- ^ "Building A Legend - Part 2". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2014-05-10. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- ^ "RIGZONE – Offshore Rig Data, Onshore Fleet Analysis". Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ a b "UPDATE 1-Shell starts production at Perdido". Reuters. March 31, 2010. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ "Contracts let for Marjan oil field development. (Saudi Arabian Oil Co. bids out offshore development contracts) (Saudi Arabia)". Middle East Economic Digest. March 27, 1992. Archived from the original on 2012-11-05. Retrieved 2011-02-26 – via Highbeam Research.

- ^ "Russian Rosneft announces major oil, gas discovery in Arctic Kara Sea". Platts. Archived from the original on 2018-01-07. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

- ^ "Year 2006 National Assessment – Alaska Outer Continental Shelf" (PDF). Dept Interior BEOM. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-09-02. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

- ^ "NOAA Ocean Explorer: Expedition to the Deep Slope". oceanexplorer.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- ^ "An Overview of Design, Analysis, Construction and Installation of Off…". October 31, 2013. Archived from the original on September 29, 2018. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ "Significant Guidance for Design and Construction of Marine and Offsho…". October 31, 2013. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ Fahey, Jonathan (December 30, 2011). "Deep Gulf drilling thrives 18 mos. after BP spill". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2020-02-03. Retrieved 2019-09-08 – via Phys.org.

- ^ Fahley, Jonathan (December 30, 2011). "The offshore drilling life: cramped and dangerous". AP News. Archived from the original on 2020-02-07. Retrieved 2019-09-08.

- ^ "First Cell Spar". Archived from the original on 2011-07-11. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Chevron Drillship". 2010-03-11. Archived from the original on 2010-05-30. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Shell starts up Stones in the ultra-deepwater Gulf of Mexico". Offshore. 2016-09-06. Retrieved 2024-07-10.

- ^ "FLNG gets serious". Gas Today. August 2010. Archived from the original on 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2018-12-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Deepwater Gulf of Mexico" (PDF). December 31, 2019. p. 65.

- ^ a b c d Maslin, Elaine (May 1, 2016). "How deep is your well?".

- ^ a b "Uruguay: First offshore well in years breaks world record". April 1, 2016.

- ^ a b "Total to Drill Deepest Ever Offshore Well Using Maersk Rig". January 14, 2020.

- ^ Jones, Dai (August 8, 2024). "Offshore Drilling Keeps Getting Deeper".

- ^ "Potential for big spill after oil rig sinks". NBC News. 2010-04-22. Archived from the original on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2010-06-04.

- ^ http://www.oilandgas.org.uk/issues/piperalpha/v0000864.cfm[permanent dead link]

- ^ "North Sea platform collapses". BBC News. 1980-03-27. Archived from the original on 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2008-06-19.

- ^ Jenkins, Brian Michael. "Potential Threats To Offshore Platforms" (PDF). The RAND Corporation.

- ^ Feloni, Richard. "Gen. Stanley McChrystal explains what most people get wrong about Navy SEALs". Business Insider.

- ^ http://www.raeng.org.uk/publications/reports/decommissioning-in-the-north-sea Archived 2014-10-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Decommissioning and Rigs-to-Reefs in the Gulf of Mexico: FAQs" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2013-11-09 – via sero.nmfs.noaa.gov.

- ^ Urbina, Ian (15 August 2015). "Vacation in Rome? Or on That Oil Rig?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021.

- ^ Page M, Dugan J, Love M, Lenihan H. "Ecological Performance and Trophic Links: Comparisons Among Platforms And Natural Reefs For Selected Fish And Their Prey". University of California, Santa Barbara. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ^ Cox SA, Beaver CR, Dokken QR, Rooker JR (1996). "Diver-based under water survey techniques used to assess fish populations and fouling community development on offshore oil and gas platform structures". In Lang MA, Baldwin CC (eds.). The Diving for Science, "Methods and Techniques of Underwater Research". Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences 16th Annual Scientific Diving Symposium, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. American Academy of Underwater Sciences (AAUS). Archived from the original on 2009-08-22. Retrieved 2008-06-27 – via Rubicon Foundation. "Full text" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2019-09-09.

- ^ Debate Over Offshore Drilling. CBS News (internet video). 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-08-24. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

- ^ Kaiser, Mark J. (October 2008). "The impact of extreme weather on offshore production in the Gulf of Mexico". Applied Mathematical Modelling. 32 (10): 1996–2018. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2007.06.031.

When a hurricane enters the GOM, oil production and transportation pipelines in the (expected) path of the storm shut down, crews are evacuated, and refineries and processing plants along the Gulf coast close. Drilling rigs pull pipe and move out of the projected path of the storm, if possible, or anchor down

- ^ Yacovitch, Tara I.; Daube, Conner; Herndon, Scott C. (2020-03-09). "Methane Emissions from Offshore Oil and Gas Platforms in the Gulf of Mexico". Environmental Science & Technology. 54 (6): 3530–3538. Bibcode:2020EnST...54.3530Y. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b07148. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 32149499.

- ^ Cartwright, Jon. "The reaction that would give us clean fossil fuels forever". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 2020-10-26. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ Technology, Karlsruhe Institute of. "Hydrogen from methane without CO2 emissions". phys.org. Archived from the original on 2020-10-21. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ BASF. "BASF researchers working on fundamentally new, low-carbon production processes, Methane Pyrolysis". United States Sustainability. BASF. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ "KITT/IASS – Producing CO2 free hydrogen from natural gas for energy usage". Archived from the original on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ Fernandez, Sonia. "low-cost, low-emissions technology that can convert methane into hydrogen without forming CO2". Phys-Org. American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ^ "The Afterlife of Old Offshore Oil Rigs – ASME". www.asme.org. American Society of Mechanical Engineers. 2019. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Old oil rigs could become CO2 storage sites". BBC News. August 8, 2019. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Watson, Jeremy. "Ageing oil rigs could be used to store carbon and fight climate change". The Times. Archived from the original on 2020-10-26. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ Burghardt, Thomas (19 January 2021). "SpaceX acquires former oil rigs to serve as floating Starship spaceports". NASASpaceFlight. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia unveils plan to build a massive adventure tourism destination 'The Rig': Check details". CNCB. 2024-01-19. Retrieved 2024-01-25.

External links

[edit]- Oil Rig Disasters Listing of oil rig accidents

- Oil Rig Photos Collection of pictures of drilling rigs and production platforms

- An independent review of offshore platforms in the North Sea

- Overview of Conventional Platforms Pictorial treatment on the installation of platforms which extend from the seabed to the ocean surface

Oil platform

View on GrokipediaHistory

Early Developments

The earliest offshore oil drilling occurred in the late 19th century near Summerland, California, where operations began in 1896 using wharves extending into the Pacific Ocean to access submerged reservoirs.[8] In 1897, the first dedicated offshore oil well was drilled from the end of a wharf approximately 300 feet off the coast, marking the initial shift from onshore to marine extraction in shallow coastal waters.[2] These rudimentary setups involved wooden piers supporting drilling equipment, with production peaking in the early 1900s as multiple wharves, such as the Treadwell Wharf, facilitated dozens of wells that yielded significant oil volumes from beachfront and subtidal fields.[4] Further early advancements extended to inland waters and Gulf Coast states, with submerged wells drilled from pile-supported platforms in Ohio's Grand Lake St. Marys around 1891, though these were in freshwater rather than oceanic environments.[4] By 1911, the first over-water oil well in a natural body was completed in Caddo Lake, Louisiana, using barge-mounted rigs to navigate shallow lake conditions and target lakebed reserves.[9] These lake-based operations employed floating or fixed barges, precursors to marine platforms, and demonstrated feasibility in accessing hydrocarbons beneath water-covered terrains amid challenges like unstable substrates.[4] Transitioning to marine settings, Gulf of Mexico drilling from state waters commenced in the 1930s with wooden fixed structures in shallow depths, exemplified by the 1938 Creole platform built by Pure Oil and Superior Oil Companies at 14 feet of water, which introduced freestanding steel-jacket designs for stability against waves and currents.[5] These early fixed platforms relied on pile-driven foundations to anchor against environmental forces, enabling production from wells up to several miles offshore while limited to water depths under 100 feet due to material and engineering constraints of the era.[10] Such developments laid the groundwork for scalable offshore infrastructure, prioritizing empirical site assessments and basic structural reinforcements over advanced technologies.[5]Mid-20th Century Expansion

![Tender and offshore oil rig platform in Louisiana Gulf of Mexico][float-right] The mid-20th century marked a significant expansion of offshore oil platform development, primarily in the Gulf of Mexico, following World War II technological advancements and growing energy demands. In October 1947, Kerr-McGee Corporation installed the Kermac 16 platform at Ship Shoal Block 16, approximately 10.5 miles offshore Louisiana in 18 feet of water, drilling the first productive well beyond sight of land.[4] This milestone shifted operations from near-shore fixed piers to self-contained steel platforms supported by tender assist vessels, enabling exploration in federal waters and demonstrating economic viability for deeper-water drilling.[11] Production from this well began in 1948, yielding over 1,000 barrels per day initially.[12] Throughout the 1950s, platform installations accelerated with improvements in welding, pile driving, and structural design, allowing fixed jacket platforms to reach water depths up to 100 feet by 1955.[13] Discoveries proliferated, with 11 new fields identified in 1949 alone from 44 exploratory wells, fueling a boom in Gulf production.[11] Mobile units like submersible barges and early jack-up rigs emerged, enhancing flexibility for exploratory drilling without permanent installations.[14] By the late 1950s, however, rising dry hole rates and capital costs tempered the pace, though cumulative infrastructure grew substantially.[12] Into the 1960s, expansion continued with platforms routinely installed in up to 200 feet of water by 1962, supported by geophysical surveys and seismic innovations.[13] By the mid-1960s, approximately 1,000 platforms operated in the Gulf across depths to 300 feet, collectively producing about one million barrels of oil daily.[15] This era's fixed platforms, predominantly steel-jacketed structures, laid the foundation for subsequent deepwater technologies while establishing the Gulf as the epicenter of global offshore production.[12]Deepwater and Modern Advancements

The transition to deepwater operations, defined as water depths exceeding 1,000 feet (305 meters), gained momentum in the 1970s amid depleting shallow-water reserves and improvements in seismic imaging and drilling vessels. In 1975, Shell Oil Company achieved the first major deepwater discovery at the Cognac field in the Gulf of Mexico, where exploratory drilling reached depths over 1,000 feet, paving the way for subsequent developments in floating rig capabilities.[16][8] Key structural innovations followed, enabling production in progressively deeper waters. Conoco installed the world's first tension-leg platform (TLP) at the Hutton field in the North Sea in 1984, in 485 feet (148 meters) of water, utilizing vertical tendons to minimize vertical motion and enhance drilling stability.[17] In the Gulf of Mexico, Placid Oil deployed the first floating production facility in 1,400 feet (427 meters) of water in 1985, followed by the Green Canyon 29 semi-submersible platform starting production in November 1988 as the initial deepwater floating oil and gas producer.[11][18] The 1990s marked accelerated adoption of advanced floating systems. Kerr-McGee's Neptune platform, installed in 1996 in 1,930 feet (588 meters) of water in the Gulf of Mexico, became the first production spar, featuring a cylindrical hull for superior stability against waves and currents in ultra-deepwater environments.[19] By the late 1990s, deepwater production volumes began surpassing those from shallow waters in key basins like the Gulf, supported by subsea tie-backs and compliant structures.[20] Modern advancements have focused on enhancing safety, efficiency, and operational reach amid ultra-deepwater challenges exceeding 5,000 feet (1,500 meters). Dynamic positioning systems, refined since the 1960s, now integrate GPS and thrusters for precise vessel control without anchors, while subsea production systems enable direct seabed processing and flowlines to shore, reducing surface infrastructure needs.[21] Enhanced blowout preventers and real-time monitoring via fiber optics and sensors mitigate risks, as demonstrated in post-2010 regulatory reforms following the Deepwater Horizon incident.[21] Recent innovations include automated drilling rigs, AI-driven predictive analytics for equipment failure, and advanced remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) for subsea maintenance, alongside dual-gradient drilling techniques that manage narrow pressure windows in complex formations.[22][23] These technologies have facilitated discoveries and production in water depths over 10,000 feet (3,000 meters), such as Brazil's pre-salt fields, sustaining global offshore output.[14]Types of Platforms

Fixed Platforms

Fixed platforms consist of rigid structures anchored directly to the seabed, primarily through steel frameworks driven into the underlying soil via piles, enabling stable operations in relatively shallow marine environments.[24] These installations feature a substructure, often a steel jacket—a lattice of tubular members providing support—and an upper deck or topsides housing drilling, production, and processing equipment.[25] Economically viable in water depths up to approximately 150 meters (500 feet), though some designs extend to 500 meters, fixed platforms exhibit high stiffness with natural periods shorter than typical wave periods, resulting in minimal dynamic displacements under environmental loads.[26] The steel jacket design originated in the mid-20th century, evolving from earlier wooden substructures used in the Gulf of Mexico during the 1930s and 1940s.[27] By 1947, Kerr-McGee completed the first offshore well from a fixed platform 10 miles off Louisiana in 18 feet of water, marking a shift to metal jackets for greater durability against corrosion and waves.[13] Construction involves fabricating the jacket onshore, towing it to site via barges, and securing it with driven or grouted piles that transfer loads to the seabed soil, a process guided by standards like API RP 2A developed since the 1960s.[28] In regions like the Gulf of Mexico and North Sea, thousands of such platforms support hydrocarbon extraction, with over 3,000 fixed structures in the U.S. Gulf alone as of recent inventories.[29] Advantages include inherent stability for long-term production and processing, lower operational costs compared to floating systems in suitable depths, and proven resilience when engineered for site-specific geohazards like soft soils or hurricanes.[25] However, limitations arise in deeper waters beyond 500 meters, where installation costs escalate due to heavier structures and piling challenges, and in high-seismic or cyclonic areas without advanced bracing, as evidenced by platform failures during Hurricane Camille in 1969, which prompted reinforced design criteria for extreme events.[24] Decommissioning involves cutting piles and removing topsides, a process regulated to minimize seabed impacts, with many North Sea platforms from the 1970s still operational after decades.[30] Examples include early Gulf installations like Creole Petroleum's 1945 platform off Louisiana and numerous North Sea jackets developed post-1960s discoveries, underpinning regional energy output.[27][26]Compliant Towers

Compliant towers are offshore platform structures engineered for intermediate water depths of 300 to 900 meters, bridging the gap between rigid fixed platforms and floating systems by incorporating controlled flexibility to accommodate environmental forces. The design features a slender, piled tower fixed to the seabed foundation, which supports topsides for drilling, production, and processing, while permitting lateral sway—typically up to 3-5% of water depth—to dissipate wave, wind, and current loads without compromising operational integrity. This flexibility, achieved via structural elements like axial tubes, ball joints, or guy wires, reduces peak stresses and material requirements compared to non-compliant fixed platforms, often using 30-50% less steel for equivalent depths.[31][32] Two primary variants exist: guyed compliant towers, stabilized by cables anchored to the seafloor, and freestanding types relying on inherent tower compliance through articulated or flexural joints. The guyed configuration, as in early designs, enhances stability in moderate depths but adds installation complexity, whereas freestanding towers simplify deployment yet demand precise dynamic analysis to ensure resonance avoidance with sea states. Both types maintain a fixed base for vertical risers and dry-tree completions, enabling reliable well intervention unlike many floating platforms.[33][34] Development originated with Exxon's Lena platform, installed in 1983 in the Gulf of Mexico at 310 meters depth, marking the first guyed compliant tower and proving viability for depths beyond conventional fixed limits. Advancements culminated in freestanding examples like Amerada Hess's Baldpate, deployed in 1998 at 503 meters in Garden Banks Block 260, utilizing a 541-meter articulated tower with suction caisson foundation for enhanced load distribution. Chevron's Petronius followed in 1998-2000 at 535 meters in Viosca Knoll, reaching a record 640-meter height and initial production of 60,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day from 23 wells.[32][34][35] Advantages include cost-effective scalability for 400-600 meter depths, where they outperform fixed platforms in material efficiency and floating options in well access simplicity, with capex reductions via modular construction and opex benefits from stable operations. However, limitations arise in ultra-deep water exceeding 900 meters due to excessive deflection risks, and their bespoke engineering has confined deployments to about five major Gulf of Mexico installations, emphasizing hurricane resilience through detuned natural periods.[36][32]Tension-leg Platforms

A tension-leg platform (TLP) consists of a buoyant hull anchored to the seafloor by vertical tendons—typically steel tubes or pipes—maintained in high pretension through the platform's excess buoyancy, which restricts vertical heave motion to less than 1 meter even in severe conditions while allowing limited horizontal excursions.[37][38] This design enables direct vertical access to subsea wells via dry-tree completions, similar to fixed platforms, and supports drilling, production, and processing operations.[39] TLPs are deployed in water depths ranging from approximately 300 meters to 1,500 meters, with capabilities extending to 2,000 meters in optimized designs, though tendon weight and fatigue limit practicality beyond this without extensions like extended tension-leg platforms (ETLPs).[40][41] The concept emerged in the 1970s to bridge the gap between fixed platforms, viable up to about 500 meters, and deeper-water floaters lacking vertical stability for well interventions.[39] The first commercial TLP, installed by Conoco in August 1984 at the Hutton field in the UK North Sea, operated in 148 meters of water and produced over 200 million barrels of oil equivalent before decommissioning in 2009.[39][42] Subsequent deployments included Shell's Auger TLP in the Gulf of Mexico in 1994 at 870 meters, ConocoPhillips' Heidrun TLP off Norway in 1995 at 350 meters, and ExxonMobil's Kizomba A ETLP in Angola in 2004 at 800 meters, demonstrating scalability for marginal fields and harsh environments.[43] By 2020, over 20 TLPs had been installed globally, primarily in the Gulf of Mexico and North Sea, contributing to fields with reserves exceeding 1 billion barrels equivalent in aggregate.[43] Structurally, the hull features multiple surface-piercing columns connected by pontoons for buoyancy, with tendons grouped in clusters (often 8-16) attached to templates on the seabed; pretension levels reach 10-20 MN per tendon to counter wave and current forces.[37] Design emphasizes fatigue-resistant materials like high-strength steel for tendons, which experience cyclic loading from platform offset, and incorporates flex joints or tapered elements to accommodate misalignment.[44] Advantages include deck payload capacities up to 20,000 tons akin to fixed platforms, reduced mooring footprint versus semi-submersibles, and operational simplicity for riser and flowline connections, lowering life-cycle costs in moderate deepwater settings.[45][46] However, disadvantages encompass high upfront fabrication costs (often 20-30% above semi-submersibles for equivalent capacity), vulnerability to tendon damage from dropped objects or corrosion requiring specialized inspection, and reduced viability in ultra-deep water over 2,000 meters due to exponential tendon costs and set-down effects reducing airgap margins.[37][47] TLPs thus suit fields with proven reserves justifying fixed-like stability without seabed soil limitations of compliant towers.[39]Spar Platforms

Spar platforms consist of a large-diameter cylindrical hull, typically 200-300 meters in length and 20-40 meters in diameter, with a ballasted lower section that provides hydrostatic stability through a low center of gravity, while the upper section supports drilling, production, and processing facilities.[48] The structure is moored to the seabed via catenary or taut mooring systems using chains, wire ropes, or synthetic lines anchored to piles or suction caissons, enabling vertical risers for dry tree completions that allow direct well intervention from the platform deck.[49] This design minimizes heave, pitch, and roll motions, making spars suitable for water depths from 600 meters up to over 2,400 meters, where fixed platforms become uneconomical.[50] The first production spar, Neptune, was installed by Oryx Energy Company in the Viosca Knoll 826 field in the Gulf of Mexico in September 1996, at a water depth of 588 meters (1,930 feet), marking the initial commercial deployment of spar technology for oil and gas extraction rather than storage.[51] Its hull measured 235 meters (770 feet) long and 21 meters (70 feet) in diameter, demonstrating feasibility for deepwater operations previously limited by platform stability.[51] Subsequent variants include truss spars, which feature a lighter lattice framework in the midsection for reduced weight and material use, as in Kerr-McGee's Boomvang and Nansen platforms installed in 2001 at depths around 1,700 meters; and cell spars, with multiple cylindrical cells for enhanced strength, exemplified by the Red Hawk spar deployed in 2006.[48] Spar platforms offer advantages in ultra-deepwater environments, including superior motion characteristics that support subsea tiebacks and gas compression without excessive dynamic loads, and the ability to withstand hurricanes with low fatigue on moorings and risers.[52] However, their large size incurs high fabrication, transportation, and installation costs—often requiring heavy-lift vessels—and limits redeployability compared to semi-submersibles, with mooring systems vulnerable to seabed soil conditions in soft sediments.[53] Examples include Anadarko's Lucius spar, moored in 2,164 meters (7,100 feet) of water and achieving first oil in 2013 after lower marine riser package intervention during Hurricane Isaac, producing from subsalt reservoirs via 10 dry wells.[50]Semi-submersible Platforms

Semi-submersible platforms consist of a main deck supported by vertical columns connected to submerged pontoons or lower hulls, which provide buoyancy while minimizing exposure to surface waves for enhanced stability.[54] This design allows operation in water depths exceeding 3,000 meters, with station-keeping achieved through mooring systems or dynamic positioning thrusters.[55] The platforms are primarily used for exploratory drilling, development drilling, and production in harsh offshore environments, such as the North Sea and Gulf of Mexico.[56] The concept originated from observations during submersible rig operations in the early 1960s, leading Shell to develop the first semi-submersible, Blue Water Rig No. 1, in 1961 by modifying an existing shallow-water submersible rig for deeper operations.[57] The inaugural purpose-built semi-submersible drilling rig, Ocean Driller, launched in 1963, marked a shift toward mobile offshore drilling units capable of withstanding rough seas.[27] By the 1970s, second-generation designs incorporated advanced mooring and subsea equipment, enabling the first oil and gas production from a floating platform in the Argyll field (North Sea) in 1975 at approximately 80 meters water depth.[56][58] Stability derives from the low metacentric height and submerged pontoons, which lower the center of gravity and reduce wave-induced motions like heave, pitch, and roll by allowing waves to pass through the open structure between columns.[54] Engineering analyses emphasize hydrostatic buoyancy from fully or partially submerged hulls, combined with ballast systems to optimize draft during transit (partially submerged for mobility) and operations (deeply submerged for stability).[59] Mooring lines or thrusters counteract environmental loads, with designs tested for extreme conditions including hurricanes and cyclones.[55] Advantages include superior seakeeping compared to drillships, large variable load capacities for drilling equipment, and adaptability to varying water depths without fixed foundations.[54][60] These platforms support payloads exceeding 10,000 tons in modern units and can be relocated for multiple wells, reducing long-term costs in remote fields.[26] However, construction and operational expenses are higher due to complex fabrication and dynamic systems, and they require significant deck space for support vessels, limiting efficiency in congested areas.[58] Notable examples include the Deepsea Delta, a sixth-generation rig operating in the North Sea since 2009, capable of drilling in 3,000-meter depths with dynamic positioning.[56] Semi-submersibles have also been repurposed as floating production systems, integrating processing facilities for fields lacking fixed infrastructure, as seen in conversions from drilling rigs in the 1980s onward.[57] Ongoing advancements focus on hybrid designs for wind energy integration and improved fatigue resistance in ultra-deepwater applications.[56]Floating Production Systems

Floating production systems (FPS) encompass moored floating vessels designed for the production, processing, and storage of hydrocarbons from offshore subsea wells, primarily deployed in deepwater environments exceeding 500 meters where fixed platforms become structurally challenging and cost-prohibitive.[61] These systems integrate topsides facilities for separation, compression, and treatment atop buoyant hulls, connected via risers and umbilicals to subsea infrastructure.[62] Development of FPS originated in the mid-1970s amid rising offshore exploration in progressively deeper waters, with initial hydrocarbon production commencing in 1975 from the Argyll field in the UK North Sea using a semi-submersible converted for storage, followed by the Castellon field off Spain in 1977, where Shell deployed the world's first dedicated floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) unit—a converted oil tanker.[63][64] This innovation addressed the limitations of pipeline-dependent fixed platforms by enabling direct offloading to shuttle tankers, facilitating access to remote or marginal fields.[65] The dominant configuration within FPS is the FPSO, a vessel-form unit capable of storing up to 2 million barrels of oil while processing daily outputs exceeding 200,000 barrels, as exemplified by TotalEnergies' Egina FPSO operational since 2018 off Nigeria.[66] As of March 2025, approximately 208 FPSOs operate globally, predominantly in regions like the Gulf of Mexico, Brazil's pre-salt basins, and West Africa, with additional variants including floating production units (FPUs) that prioritize processing without integrated storage.[67][64] Key advantages of FPS include redeployability to new reservoirs post-field depletion, reducing long-term capital outlay compared to bespoke fixed installations, and operational flexibility in ultra-deep waters up to 3,000 meters without requiring subsea export pipelines.[68][69] They also support phased development, allowing initial production via leased units before permanent infrastructure.[70] However, challenges arise from inherent hull motions induced by waves, wind, and currents—mitigated through turret mooring systems permitting weathervaning—which demand specialized disconnectable risers and processing equipment tolerant of dynamic conditions.[71] Storage constraints necessitate frequent offloading, potentially exposing operations to weather delays, while conversion from existing tankers can introduce integrity risks if not rigorously refurbished.[72] Despite these, FPS have proven resilient, with safety records bolstered by redundant systems and regulatory oversight from bodies like the American Bureau of Shipping, which classed the first U.S. FPSO in 1978.[73]Jack-up Rigs

Jack-up rigs are mobile offshore drilling units consisting of a buoyant hull supported by three or four movable legs that can be extended to the seabed, elevating the hull above the water surface to create a stable working platform.[74] The legs, typically truss-structured for shallow water operations or cylindrical for deeper applications, are lowered via a hydraulic or electric jacking system after the rig is towed to the site, achieving an air gap of 10-20 meters between the hull and sea level to mitigate wave impact.[75] Primarily used for exploratory and development drilling in shallow waters, these rigs enable efficient operations without the need for fixed foundations, though they are not designed for long-term production.[76] The concept of jack-up rigs emerged in the late 1940s, with the first operational unit contracted in 1954 by Zapata Off-Shore Company, led by future U.S. President George H.W. Bush, marking a shift from submersible barges to self-elevating platforms for improved stability in the Gulf of Mexico.[4] Construction of early models, such as those built at LeTourneau's shipyard in Vicksburg, Mississippi, began in late 1954, incorporating designs by innovators like Leon B. Delong to address mobility limitations of fixed platforms.[57] By the 1960s, jack-ups proliferated, enabling drilling in water depths previously uneconomical, and by 2013, approximately 540 units were in global operation. Modern jack-up rigs operate in water depths ranging from 3 meters to 125 meters for standard units, with advanced designs capable of 350 feet (107 meters) or more in harsher environments, including wave heights up to 80 feet and winds exceeding 100 knots.[74][77] Their advantages include high mobility via towing, reduced setup time compared to fixed platforms, and cost-effectiveness in shallow waters, providing a stable base that minimizes heave during drilling.[74] Limitations encompass vulnerability to seabed soil conditions, which can lead to leg penetration or buckling if not pre-assessed via geotechnical surveys, and restricted applicability in deeper waters beyond 500 feet, where floating rigs are preferred. Safety incidents, such as the 2002 buckling of Arabdrill 19's leg in Saudi Arabia's Khafji Field or the 2008 movement-related event involving Hercules 203 in the Gulf of Mexico, underscore the importance of site-specific assessments and adherence to standards like those from the International Association of Drilling Contractors.[79][80]Drillships

Drillships are self-propelled maritime vessels engineered for offshore exploratory and developmental drilling of oil and gas wells, distinguished by their ship-like hulls that enable transit under their own power to drilling sites. Equipped with a central moonpool through which drilling operations occur, a derrick for handling drill strings, and dynamic positioning (DP) systems for precise station-keeping, drillships represent a mobile alternative to fixed or semi-submersible platforms. These vessels typically incorporate thrusters and propulsion units controlled by computerized systems to counteract environmental forces like currents and winds, eliminating the need for mooring anchors in many operations.[81][82] The development of drillships accelerated in the mid-20th century amid demands for accessing deeper hydrocarbon reserves, with the Sedco 445 marking a pivotal advancement as the first purpose-built, dynamically positioned drillship deployed in 1971 for Shell Oil by Sedco (now part of Transocean). This vessel introduced the integration of a marine riser and subsea blowout preventer (BOP) in a DP-configured ship, enabling safer and more efficient deepwater well control during exploratory drilling off South Java from 1972 to 1973. Earlier precursors existed, such as converted merchant ships used in the 1950s, but lacked the self-propulsion and advanced DP capabilities that defined modern iterations, which proliferated in the 1980s and beyond as water depths pushed beyond 3,000 meters.[83][84] Contemporary drillships boast ultra-deepwater capabilities, routinely operating in water depths up to 12,000 feet (3,658 meters) and drilling to total depths exceeding 40,000 feet (12,192 meters), as exemplified by vessels like the Deepwater Invictus and Deepwater Conqueror in Transocean's fleet. Design features include reinforced hulls for seaworthiness, onboard accommodations for 120-200 personnel, and auxiliary systems for mud circulation, power generation, and riser storage to support extended campaigns in remote basins such as the Gulf of Mexico or West Africa. These specifications allow drillships to target subsalt and pre-salt formations inaccessible to shallower-water rigs, though operations demand rigorous maintenance of DP integrity to mitigate risks from heave compensation and station drift.[85][86] Drillships offer advantages in mobility and deployment flexibility over moored or bottom-supported structures, facilitating rapid relocation across global frontiers and reducing downtime between wells, which enhances economic viability in high-cost deepwater projects. However, their reliance on continuous power and fuel for DP systems increases operational complexity and vulnerability to mechanical failures, as evidenced by historical incidents where positioning losses led to well deviations or emergency disconnects. Fleet examples include the Saipem 10000, capable of 10,000 feet (3,048 meters) water depth since its introduction in the early 2000s, underscoring the iterative enhancements in propulsion redundancy and automation that have sustained their role in frontier exploration.[87][88]Gravity-based Structures

Gravity-based structures (GBS) are offshore platforms that rely on their substantial mass, typically composed of reinforced concrete, to maintain stability through gravitational forces against the seabed, resisting overturning and sliding from waves, currents, and wind without requiring deep pile foundations. These structures apply vertical pressure to the seabed, leveraging friction and soil bearing capacity for anchorage, and are commonly used in water depths up to several hundred meters where seabed conditions provide adequate support.[89][90] Design of GBS often incorporates a cellular or conical base with multiple caissons or legs filled with ballast, such as sand or water, to enhance weight and lower the center of gravity, minimizing hydrodynamic loads; skirts or pads at the base penetrate the seabed for additional resistance to lateral forces. Construction typically occurs in protected coastal basins or dry docks, where the base is fabricated in modules, floated out after completion, and towed to the installation site before controlled ballasting to seat it firmly on the seabed. This method allows for modular topside integration either prior to towing or via float-over installation post-placement.[91][92] Compared to piled fixed platforms, GBS offer advantages in installation simplicity and potential reusability, as they can be deballasted, refloated, and relocated, reducing long-term costs in marginal fields; they also provide inherent storage capacity within base cells for oil or water ballast. However, their immense weight—often exceeding hundreds of thousands of tons—demands robust seabed geotechnics to prevent settlement or liquefaction, limiting applicability in soft soils or ultra-deep waters without hybrid foundations, and construction requires specialized facilities capable of handling massive concrete pours.[90][93][92] Prominent examples include the Troll A platform in the North Sea, installed in 1996, which features a Condeep-type GBS with four massive concrete legs, each over 1 meter thick in walls, weighing approximately 683,600 tons and standing 472 meters tall including topsides—the tallest structure ever transported by sea over 200 kilometers from its construction site at Vats, Norway. The Troll A base, designed for 303-meter water depth, utilized 245,000 cubic meters of concrete and 100,000 tons of steel reinforcement to withstand extreme environmental loads, demonstrating GBS feasibility in challenging Arctic conditions. Earlier Brent Field platforms, constructed in the 1970s, exemplified initial GBS deployments with concrete bases engineered for 25-meter waves and 200-mile-per-hour winds.[94][95][96]Normally Unmanned Installations

Normally unmanned installations (NUIs), also known as unattended platforms, are compact offshore structures designed for remote operation without a permanent onboard crew, relying on automation, sensors, and periodic human interventions for maintenance and well work. These platforms typically process hydrocarbons from marginal fields with limited reserves, tying back production to nearby manned facilities or onshore control centers via subsea pipelines and umbilicals. NUIs are favored in regions like the North Sea for water depths up to 125 meters, where constructing multiple small units proves more economical than large manned platforms.[97][98] Key design elements include simplified topsides with minimal processing equipment, no accommodation modules, and robust remote monitoring systems for real-time data on pressure, flow rates, and integrity. Power is often supplied via subsea cables or diesel generators activated remotely, while safety features incorporate emergency shutdown valves, fire suppression, and temporary shelters for visiting personnel during evacuations or repairs. Access occurs via boat landings, helicopters, or walk-to-work vessels with gangways, with platforms flushed and isolated from hydrocarbons during idle periods to mitigate environmental risks. Industry analyses highlight NUIs' lower capital expenditure—often 20-50% less than manned equivalents—due to reduced steel weight and fabrication complexity, alongside operational savings from eliminating crew rotations and logistics.[99][100][101] Deployment of NUIs enhances recovery from stranded assets by minimizing personnel exposure to hazards, though challenges include dependency on reliable automation and rapid response capabilities for faults, as delays in physical access can halt production. A 2016 Norwegian Petroleum Directorate study identified advantages in lifecycle costs and safety but noted potential drawbacks like higher upfront automation investments and limitations in handling complex interventions without nearby support. Examples include Equinor's Oseberg H platform, installed in 2018 off Norway and remotely controlled from the Oseberg field center, producing without onboard facilities; BP's Hod B, tied back to Valhall in the Norwegian North Sea; and IOG's Blythe and Southwark NUIs in the UK Southern North Sea, mechanically completed in April 2021 for gas production. Other North Sea cases, such as Tambar (BP) and Embla (ConocoPhillips), operate in 70-125 meter depths with unmanned profiles.[102][103][104][105]Design and Construction

Engineering Principles