Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Transparency and translucency

View on Wikipedia

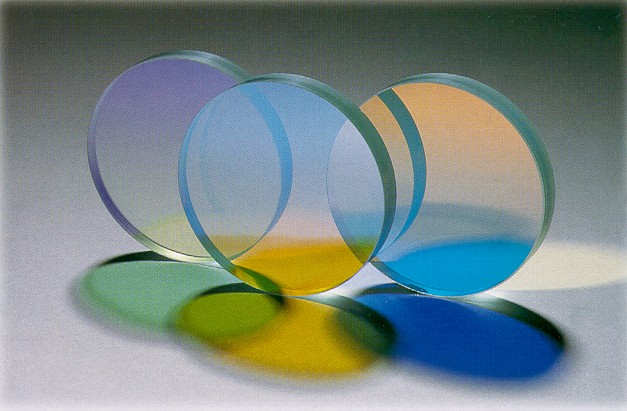

In the field of optics, transparency (also called pellucidity or diaphaneity) is the physical property of allowing light to pass through the material without appreciable scattering of light. On a macroscopic scale (one in which the dimensions are much larger than the wavelengths of the photons in question), the photons can be said to follow Snell's law. Translucency (also called translucence or translucidity) is the physical property of allowing light to pass through the material (with or without scattering of light). It allows light to pass through but the light does not necessarily follow Snell's law on the macroscopic scale; the photons may be scattered at either of the two interfaces, or internally, where there is a change in the index of refraction. In other words, a translucent material is made up of components with different indices of refraction. A transparent material is made up of components with a uniform index of refraction.[1] Transparent materials appear clear, with the overall appearance of one color, or any combination leading up to a brilliant spectrum of every color. The opposite property of translucency is opacity. Other categories of visual appearance, related to the perception of regular or diffuse reflection and transmission of light, have been organized under the concept of cesia in an order system with three variables, including transparency, translucency and opacity among the involved aspects.

When light encounters a material, it can interact with it in several different ways. These interactions depend on the wavelength of the light and the nature of the material. Photons interact with an object by some combination of reflection, absorption and transmission. Some materials, such as plate glass and clean water, transmit much of the light that falls on them and reflect little of it; such materials are called optically transparent. Many liquids and aqueous solutions are highly transparent. Absence of structural defects (voids, cracks, etc.) and molecular structure of most liquids are mostly responsible for excellent optical transmission.

Materials that do not transmit light are called opaque. Many such substances have a chemical composition which includes what are referred to as absorption centers. Many substances are selective in their absorption of white light frequencies. They absorb certain portions of the visible spectrum while reflecting others. The frequencies of the spectrum which are not absorbed are either reflected or transmitted for our physical observation. This is what gives rise to color. The attenuation of light of all frequencies and wavelengths is due to the combined mechanisms of absorption and scattering.[2]

Transparency can provide almost perfect camouflage for animals able to achieve it. This is easier in dimly-lit or turbid seawater than in good illumination. Many marine animals such as jellyfish are highly transparent.

Etymology

[edit]- late Middle English: from Old French, from medieval Latin transparent- 'visible through', from Latin transparere, from trans- 'through' + parere 'be visible'.[citation needed]

- late 16th century (in the Latin sense): from Latin translucent- 'shining through', from the verb translucere, from trans- 'through' + lucere 'to shine'.[citation needed]

- late Middle English opake, from Latin opacus 'darkened'. The current spelling (rare before the 19th century) has been influenced by the French form.[citation needed]

Introduction

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

With regard to the absorption of light, primary material considerations include:

- At the electronic level, absorption in the ultraviolet and visible (UV-Vis) portions of the spectrum depends on whether the electron orbitals are spaced (or "quantized") such that electrons can absorb a quantum of light (or photon) of a specific frequency. For example, in most glasses, electrons have no available energy levels above them in the range of that associated with visible light, or if they do, the transition to them would violate selection rules, meaning there is no appreciable absorption in pure (undoped) glasses, making them ideal transparent materials for windows in buildings.

- At the atomic or molecular level, physical absorption in the infrared portion of the spectrum depends on the frequencies of atomic or molecular vibrations or chemical bonds, and on selection rules. Nitrogen and oxygen are not greenhouse gases because there is no molecular dipole moment.

With regard to the scattering of light, the most critical factor is the length scale of any or all of these structural features relative to the wavelength of the light being scattered. Primary material considerations include:

- Crystalline structure: whether the atoms or molecules exhibit the 'long-range order' evidenced in crystalline solids.

- Glassy structure: Scattering centers include fluctuations in density or composition.

- Microstructure: Scattering centers include internal surfaces such as grain boundaries, crystallographic defects, and microscopic pores.

- Organic materials: Scattering centers include fiber and cell structures and boundaries.

Diffuse reflection - Generally, when light strikes the surface of a (non-metallic and non-glassy) solid material, it bounces off in all directions due to multiple reflections by the microscopic irregularities inside the material (e.g., the grain boundaries of a polycrystalline material or the cell or fiber boundaries of an organic material), and by its surface, if it is rough. Diffuse reflection is typically characterized by omni-directional reflection angles. Most of the objects visible to the naked eye are identified via diffuse reflection. Another term commonly used for this type of reflection is "light scattering". Light scattering from the surfaces of objects is our primary mechanism of physical observation.[3][4]

Light scattering in liquids and solids depends on the wavelength of the light being scattered. Limits to spatial scales of visibility (using white light) therefore arise, depending on the frequency of the light wave and the physical dimension (or spatial scale) of the scattering center. Visible light has a wavelength scale on the order of 0.5 μm. Scattering centers (or particles) as small as 1 μm have been observed directly in the light microscope (e.g., Brownian motion).[5][6]

Transparent ceramics

[edit]Optical transparency in polycrystalline materials is limited by the amount of light scattered by their microstructural features. Light scattering depends on the wavelength of the light. Limits to spatial scales of visibility (using white light) therefore arise, depending on the frequency of the light wave and the physical dimension of the scattering center. For example, since visible light has a wavelength scale on the order of a micrometre, scattering centers will have dimensions on a similar spatial scale. Primary scattering centers in polycrystalline materials include microstructural defects such as pores and grain boundaries. In addition to pores, most of the interfaces in a typical metal or ceramic object are in the form of grain boundaries, which separate tiny regions of crystalline order. When the size of the scattering center (or grain boundary) is reduced below the size of the wavelength of the light being scattered, the scattering no longer occurs to any significant extent.

In the formation of polycrystalline materials (metals and ceramics) the size of the crystalline grains is determined largely by the size of the crystalline particles present in the raw material during formation (or pressing) of the object. Moreover, the size of the grain boundaries scales directly with particle size. Thus, a reduction of the original particle size well below the wavelength of visible light (about 1/15 of the light wavelength, or roughly 600 nm / 15 = 40 nm) eliminates much of the light scattering, resulting in a translucent or even transparent material.

Computer modeling of light transmission through translucent ceramic alumina has shown that microscopic pores trapped near grain boundaries act as primary scattering centers. The volume fraction of porosity had to be reduced below 1% for high-quality optical transmission (99.99 percent of theoretical density). This goal has been readily accomplished and amply demonstrated in laboratories and research facilities worldwide using the emerging chemical processing methods encompassed by the methods of sol-gel chemistry and nanotechnology.[7]

Transparent ceramics have created interest in their applications for high energy lasers, transparent armor windows, nose cones for heat seeking missiles, radiation detectors for non-destructive testing, high energy physics, space exploration, security and medical imaging applications. Large laser elements made from transparent ceramics can be produced at a relatively low cost. These components are free of internal stress or intrinsic birefringence, and allow relatively large doping levels or optimized custom-designed doping profiles. This makes ceramic laser elements particularly important for high-energy lasers.

The development of transparent panel products will have other potential advanced applications including high strength, impact-resistant materials that can be used for domestic windows and skylights. Perhaps more important is that walls and other applications will have improved overall strength, especially for high-shear conditions found in high seismic and wind exposures. If the expected improvements in mechanical properties bear out, the traditional limits seen on glazing areas in today's building codes could quickly become outdated if the window area actually contributes to the shear resistance of the wall.

Currently available infrared transparent materials typically exhibit a trade-off between optical performance, mechanical strength and price. For example, sapphire (crystalline alumina) is very strong, but it is expensive and lacks full transparency throughout the 3–5 μm mid-infrared range. Yttria is fully transparent from 3–5 μm, but lacks sufficient strength, hardness, and thermal shock resistance for high-performance aerospace applications. A combination of these two materials in the form of the yttrium aluminium garnet (YAG) is one of the top performers in the field.[citation needed]

Absorption of light in solids

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

When light strikes an object, it usually has not just a single frequency (or wavelength) but many. Objects have a tendency to selectively absorb, reflect, or transmit light of certain frequencies. That is, one object might reflect green light while absorbing all other frequencies of visible light. Another object might selectively transmit blue light while absorbing all other frequencies of visible light. The manner in which visible light interacts with an object is dependent upon the frequency of the light, the nature of the atoms in the object, and often, the nature of the electrons in the atoms of the object.

Some materials allow much of the light that falls on them to be transmitted through the material without being reflected. Materials that allow the transmission of light waves through them are called optically transparent. Chemically pure (undoped) window glass and clean river or spring water are prime examples of this.

Materials that do not allow the transmission of any light wave frequencies are called opaque. Such substances may have a chemical composition which includes what are referred to as absorption centers. Most materials are composed of materials that are selective in their absorption of light frequencies. Thus they absorb only certain portions of the visible spectrum. The frequencies of the spectrum which are not absorbed are either reflected back or transmitted for our physical observation. In the visible portion of the spectrum, this is what gives rise to color.[8][9]

Absorption centers are largely responsible for the appearance of specific wavelengths of visible light all around us. Moving from longer (0.7 μm) to shorter (0.4 μm) wavelengths: Red, orange, yellow, green, and blue (ROYGB) can all be identified by our senses in the appearance of color by the selective absorption of specific light wave frequencies (or wavelengths). Mechanisms of selective light wave absorption include:

- Electronic: Transitions in electron energy levels within the atom (e.g., pigments). These transitions are typically in the ultraviolet (UV) and/or visible portions of the spectrum.

- Vibrational: Resonance in atomic/molecular vibrational modes. These transitions are typically in the infrared portion of the spectrum.

UV-Vis: electronic transitions

[edit]In electronic absorption, the frequency of the incoming light wave is at or near the energy levels of the electrons within the atoms that compose the substance. In this case, the electrons will absorb the energy of the light wave and increase their energy state, often moving outward from the nucleus of the atom into an outer shell or orbital.

The atoms that bind together to make the molecules of any particular substance contain a number of electrons (given by the atomic number Z in the periodic table). Recall that all light waves are electromagnetic in origin. Thus they are affected strongly when coming into contact with negatively charged electrons in matter. When photons (individual packets of light energy) come in contact with the valence electrons of an atom, one of several things can and will occur:

- A molecule absorbs the photon, some of the energy may be lost via luminescence, fluorescence and phosphorescence.

- A molecule absorbs the photon, which results in reflection or scattering.

- A molecule cannot absorb the energy of the photon and the photon continues on its path. This results in transmission (provided no other absorption mechanisms are active).

Most of the time, it is a combination of the above that happens to the light that hits an object. The states in different materials vary in the range of energy that they can absorb. Most glasses, for example, block ultraviolet (UV) light. What happens is the electrons in the glass absorb the energy of the photons in the UV range while ignoring the weaker energy of photons in the visible light spectrum. But there are also existing special glass types, like special types of borosilicate glass or quartz that are UV-permeable and thus allow a high transmission of ultraviolet light.

Thus, when a material is illuminated, individual photons of light can make the valence electrons of an atom transition to a higher electronic energy level. The photon is destroyed in the process and the absorbed radiant energy is transformed to electric potential energy. Several things can happen, then, to the absorbed energy: It may be re-emitted by the electron as radiant energy (in this case, the overall effect is in fact a scattering of light), dissipated to the rest of the material (i.e., transformed into heat), or the electron can be freed from the atom (as in the photoelectric effects and Compton effects).

Infrared: bond stretching

[edit]

The primary physical mechanism for storing mechanical energy of motion in condensed matter is through heat, or thermal energy. Thermal energy manifests itself as energy of motion. Thus, heat is motion at the atomic and molecular levels. The primary mode of motion in crystalline substances is vibration. Any given atom will vibrate around some mean or average position within a crystalline structure, surrounded by its nearest neighbors. This vibration in two dimensions is equivalent to the oscillation of a clock's pendulum. It swings back and forth symmetrically about some mean or average (vertical) position. Atomic and molecular vibrational frequencies may average on the order of 1012 cycles per second (Terahertz radiation).

When a light wave of a given frequency strikes a material with particles having the same or (resonant) vibrational frequencies, those particles will absorb the energy of the light wave and transform it into thermal energy of vibrational motion. Since different atoms and molecules have different natural frequencies of vibration, they will selectively absorb different frequencies (or portions of the spectrum) of infrared light. Reflection and transmission of light waves occur because the frequencies of the light waves do not match the natural resonant frequencies of vibration of the objects. When infrared light of these frequencies strikes an object, the energy is reflected or transmitted.

If the object is transparent, then the light waves are passed on to neighboring atoms through the bulk of the material and re-emitted on the opposite side of the object. Such frequencies of light waves are said to be transmitted.[10][11]

Transparency in insulators

[edit]An object may be not transparent either because it reflects the incoming light or because it absorbs the incoming light. Almost all solids reflect a part and absorb a part of the incoming light.

When light falls onto a block of metal, it encounters atoms that are tightly packed in a regular lattice and a "sea of electrons" moving randomly between the atoms.[12] In metals, most of these are non-bonding electrons (or free electrons) as opposed to the bonding electrons typically found in covalently bonded or ionically bonded non-metallic (insulating) solids. In a metallic bond, any potential bonding electrons can easily be lost by the atoms in a crystalline structure. The effect of this delocalization is simply to exaggerate the effect of the "sea of electrons". As a result of these electrons, most of the incoming light in metals is reflected back, which is why we see a shiny metal surface.

Most insulators (or dielectric materials) are held together by ionic bonds. Thus, these materials do not have free conduction electrons, and the bonding electrons reflect only a small fraction of the incident wave. The remaining frequencies (or wavelengths) are free to propagate (or be transmitted). This class of materials includes all ceramics and glasses.

If a dielectric material does not include light-absorbent additive molecules (pigments, dyes, colorants), it is usually transparent to the spectrum of visible light. Color centers (or dye molecules, or "dopants") in a dielectric absorb a portion of the incoming light. The remaining frequencies (or wavelengths) are free to be reflected or transmitted. This is how colored glass is produced.

Most liquids and aqueous solutions are highly transparent. For example, water, cooking oil, rubbing alcohol, air, and natural gas are all clear. Absence of structural defects (voids, cracks, etc.) and molecular structure of most liquids are chiefly responsible for their excellent optical transmission. The ability of liquids to "heal" internal defects via viscous flow is one of the reasons why some fibrous materials (e.g., paper or fabric) increase their apparent transparency when wetted. The liquid fills up numerous voids making the material more structurally homogeneous.[citation needed]

Light scattering in an ideal defect-free crystalline (non-metallic) solid that provides no scattering centers for incoming light will be due primarily to any effects of anharmonicity within the ordered lattice. Light transmission will be highly directional due to the typical anisotropy of crystalline substances, which includes their symmetry group and Bravais lattice. For example, the seven different crystalline forms of quartz silica (silicon dioxide, SiO2) are all clear, transparent materials.[13]

Optical waveguides

[edit]

Optically transparent materials focus on the response of a material to incoming light waves of a range of wavelengths. Guided light wave transmission via frequency selective waveguides involves the emerging field of fiber optics and the ability of certain glassy compositions to act as a transmission medium for a range of frequencies simultaneously (multi-mode optical fiber) with little or no interference between competing wavelengths or frequencies. This resonant mode of energy and data transmission via electromagnetic (light) wave propagation is relatively lossless.[citation needed]

An optical fiber is a cylindrical dielectric waveguide that transmits light along its axis by the process of total internal reflection. The fiber consists of a core surrounded by a cladding layer. To confine the optical signal in the core, the refractive index of the core must be greater than that of the cladding. The refractive index is the parameter reflecting the speed of light in a material. (Refractive index is the ratio of the speed of light in vacuum to the speed of light in a given medium. The refractive index of vacuum is therefore 1.) The larger the refractive index, the more slowly light travels in that medium. Typical values for core and cladding of an optical fiber are 1.48 and 1.46, respectively.[citation needed]

When light traveling in a dense medium hits a boundary at a steep angle, the light will be completely reflected. This effect, called total internal reflection, is used in optical fibers to confine light in the core. Light travels along the fiber bouncing back and forth off of the boundary. Because the light must strike the boundary with an angle greater than the critical angle, only light that enters the fiber within a certain range of angles will be propagated. This range of angles is called the acceptance cone of the fiber. The size of this acceptance cone is a function of the refractive index difference between the fiber's core and cladding. Optical waveguides are used as components in integrated optical circuits (e.g., combined with lasers or light-emitting diodes, LEDs) or as the transmission medium in local and long-haul optical communication systems.[citation needed]

Mechanisms of attenuation

[edit]

Attenuation in fiber optics, also known as transmission loss, is the reduction in intensity of the light beam (or signal) with respect to distance traveled through a transmission medium. It is an important factor limiting the transmission of a signal across large distances. Attenuation coefficients in fiber optics usually use units of dB/km through the medium due to the very high quality of transparency of modern optical transmission media. The medium is usually a fiber of silica glass that confines the incident light beam to the inside.

In optical fibers, the main source of attenuation is scattering from molecular level irregularities, called Rayleigh scattering,[15] due to structural disorder and compositional fluctuations of the glass structure. This same phenomenon is seen as one of the limiting factors in the transparency of infrared missile domes.[16] Further attenuation is caused by light absorbed by residual materials, such as metals or water ions, within the fiber core and inner cladding. Light leakage due to bending, splices, connectors, or other outside forces are other factors resulting in attenuation. At high optical powers, scattering can also be caused by nonlinear optical processes in the fiber.[17]

As camouflage

[edit]

Many marine animals that float near the surface are highly transparent, giving them almost perfect camouflage.[18] However, transparency is difficult for bodies made of materials that have different refractive indices from seawater. Some marine animals such as jellyfish have gelatinous bodies, composed mainly of water; their thick mesogloea is acellular and highly transparent. This conveniently makes them buoyant, but it also makes them large for their muscle mass, so they cannot swim fast, making this form of camouflage a costly trade-off with mobility.[18] Gelatinous planktonic animals are between 50 and 90 percent transparent. A transparency of 50 percent is enough to make an animal invisible to a predator such as cod at a depth of 650 metres (2,130 ft); better transparency is required for invisibility in shallower water, where the light is brighter and predators can see better. For example, a cod can see prey that are 98 percent transparent in optimal lighting in shallow water. Therefore, sufficient transparency for camouflage is more easily achieved in deeper waters.[18] For the same reason, transparency in air is even harder to achieve, but a partial example is found in the glass frogs of the South American rain forest, which have translucent skin and pale greenish limbs.[19] Several Central American species of clearwing (ithomiine) butterflies and many dragonflies and allied insects also have wings which are mostly transparent, a form of crypsis that provides some protection from predators.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Thomas, S. M. (October 21, 1999). "What determines whether a substance is transparent?". Scientific American.

- ^ Fox, M. (2002). Optical Properties of Solids. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Kerker, M. (1969). The Scattering of Light. Academic, New York.

- ^ Mandelstam, L.I. (1926). "Light Scattering by Inhomogeneous Media". Zh. Russ. Fiz-Khim. Ova. 58: 381.

- ^ van de Hulst, H.C. (1981). Light scattering by small particles. New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-64228-3.

- ^ Bohren, C.F. & Huffmann, D.R. (1983). Absorption and scattering of light by small particles. New York: Wiley.

- ^ Yamashita, I.; et al. (2008). "Transparent Ceramics". J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 91 (3): 813. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2007.02202.x.

- ^ Simmons, J. & Potter, K.S. (2000). Optical Materials. Academic Press.

- ^ Uhlmann, D.R.; et al. (1991). Optical Properties of Glass. Amer. Ceram. Soc.

- ^ Gunzler, H. & Gremlich, H. (2002). IR Spectroscopy: An Introduction. Wiley.

- ^ Stuart, B. (2004). Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications. Wiley.

- ^ Mott, N.F. & Jones, H. Theory of the Properties of Metals and Alloys. Clarendon Press, Oxford (1936) Dover Publications (1958).

- ^ Griffin, A. (1968). "Brillouin Light Scattering from Crystals in the Hydrodynamic Region". Rev. Mod. Phys. 40 (1): 167. Bibcode:1968RvMP...40..167G. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.40.167.

- ^ Khrapko, R.; Logunov, S. L.; Li, M.; Matthews, H. B.; Tandon, P.; Zhou, C. (2024-04-15). "Quasi Single-Mode Fiber With Record-Low Attenuation of 0.1400 dB/km". IEEE Photonics Technology Letters. 36 (8): 539–542. Bibcode:2024IPTL...36..539K. doi:10.1109/LPT.2024.3372786. ISSN 1041-1135.

- ^ I. P. Kaminow, T. Li (2002), Optical fiber telecommunications IV, Vol. 1, p. 223 Archived 2013-05-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Archibald, P.S. & Bennett, H.E. (1978). Benton, Stephen A. & Knight, Geoffery (eds.). "Scattering from infrared missile domes". Opt. Eng. Optics in Missile Engineering. 17: 647. Bibcode:1978SPIE..133...71A. doi:10.1117/12.956078. S2CID 173179565.

- ^ Smith, R.G. (1972). "Optical power handling capacity of low loss optical fibers as determined by stimulated Raman and Brillouin scattering". Appl. Opt. 11 (11): 2489–94. Bibcode:1972ApOpt..11.2489S. doi:10.1364/AO.11.002489. PMID 20119362.

- ^ a b c Herring, Peter (2002). The Biology of the Deep Ocean. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854956-7. pp. 190–191.

- ^ Naish, D. "Green-boned glass frogs, monkey frogs, toothless toads". Tetrapod zoology. scienceblogs.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Electrodynamics of continuous media, Landau, L. D., Lifshits. E.M. and Pitaevskii, L.P., (Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1984)

- Laser Light Scattering: Basic Principles and Practice Chu, B., 2nd Edn. (Academic Press, New York 1992)

- Solid State Laser Engineering, W. Koechner (Springer-Verlag, New York, 1999)

- Introduction to Chemical Physics, J.C. Slater (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1939)

- Modern Theory of Solids, F. Seitz, (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1940)

- Modern Aspects of the Vitreous State, J.D.MacKenzie, Ed. (Butterworths, London, 1960)

External links

[edit]Transparency and translucency

View on GrokipediaDefinitions and Etymology

Etymology

The term "transparency" derives from the Medieval Latin transparentia, first attested in the early 15th century, referring to the quality of allowing light to pass through clearly; it stems from the present participle transparens of transparēre, meaning "to shine through" or "appear through," a compound of trans- ("across" or "through") and parēre ("to appear" or "be visible").[3][4] This Latin root entered English via Old French transparence in the late 14th century for the adjective "transparent," with the noun form "transparency" appearing by the 1590s to describe the state of being see-through, initially in contexts of clarity in substances like glass or air.[5][4] "Translucency," by contrast, originates from Medieval Latin translucentia (early 15th century), denoting faint or indistinct light passage, derived from translucēns, the present participle of translucēre ("to shine through"), combining trans- ("through") and lucēre ("to shine").[6] The noun entered English around 1598, but its scientific application to distinguish partial, diffused light transmission from full transparency emerged in the 19th century, as optics advanced to differentiate materials like frosted glass that allow light but obscure form.[7][8] Related terms such as "diaphanous" trace back to Ancient Greek diaphanḗs ("showing through" or "transparent"), from diaphainein ("to show through"), a blend of dia- ("through") and phaínein ("to show" or "appear"); it entered English via Medieval Latin diaphanus in the late 14th century, originally describing sheer fabrics in poetic or literary senses before shifting to optical properties in scientific discourse by the 17th century.[9][10] In early modern texts like Isaac Newton's Opticks (1704), terms like "transparent" appear frequently to describe light passage through media without a rigid distinction from partial translucency, reflecting the era's evolving understanding of optical phenomena.[11]Transparency

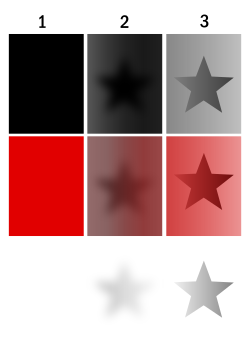

Transparency is the physical property of a material that allows light to pass through it with minimal absorption, scattering, or distortion due to refraction, enabling clear and undistorted visibility of objects on the other side.[12][13] In optical terms, this means the material transmits light primarily through regular (specular) transmission, preserving the direction and coherence of the light rays to form sharp images.[12] Materials exhibiting transparency appear colorless or nearly so in the visible spectrum unless inherent colorants or impurities alter this.[14] Quantitatively, transparency is often characterized by a high transmission coefficient , typically greater than 90% across the visible wavelengths from 400 to 700 nm, alongside a stable refractive index (around 1.5 for common glasses) and negligible diffuse reflection or scattering.[15][16] The transmission coefficient is defined as , where is the transmitted intensity and is the incident intensity, accounting for both absorption and reflection losses.[17] For practical assessment, internal transmittance (excluding surface reflections) exceeds 99% in high-quality optical glasses like N-BK7 over this range for thicknesses up to 25 mm.[14] Transparency can be categorized into perfect, ideal, and practical types. Perfect transparency occurs in media like vacuum or dry air, where light passes without any attenuation or deviation, akin to no material presence.[12] Ideal transparency is a theoretical construct assuming zero absorption and scattering, serving as a benchmark for material design.[12] Practical transparency, as seen in everyday materials, involves minor losses; for instance, standard soda-lime glass achieves approximately 92% total transmittance in the visible spectrum due to slight absorption and about 8% reflection at surfaces.[16][18] Several factors influence transparency, including wavelength dependence and material thickness. Transmission varies with wavelength because materials have specific absorption bands; for example, many glasses transmit well in the visible but absorb in the ultraviolet below 350 nm.[19] Thickness affects transmittance according to Beer's law: , where is the absorption coefficient and is the thickness, showing exponential decay with increasing depth. Representative examples include clear soda-lime glass (T ≈ 90-92%), pure water (nearly 100% for thin layers), and diamond (over 99% due to its wide bandgap).[15][16][18]Translucency

Translucency refers to the optical property of a material that allows light to pass through while undergoing significant diffusion due to scattering, resulting in softened or blurred images rather than clear visibility of objects behind it.[13] This diffusion occurs because the material transmits light in a non-direct manner, typically with visible light transmittance ranging from approximately 10% to 90%, though the output is predominantly diffuse rather than specular.[20] Unlike opacity, which fully blocks light and prevents any transmission, translucency permits light to emerge from the material but scatters it in multiple directions, avoiding straight-line propagation and thus obscuring detailed views.[13] In quantitative terms, translucency arises when the scattering coefficient (σ_s) significantly exceeds the absorption coefficient (α), often by a factor of 10 to 1000 in biological tissues, leading to forward-peaked diffusion that can be modeled using the Henyey-Greenstein phase function for accurate simulation of light paths.[21][22] Common examples of translucent materials include frosted glass, which scatters light through surface etching; clouds, where water droplets cause diffuse transmission; human skin, exhibiting subsurface scattering; and marble, with its veined structure promoting blurred illumination.[23] To measure translucency, diffuse transmittance is quantified using integrating spheres, which capture scattered light from both sides of the sample to determine the total diffused output relative to incident light.[23]Principles of Light Interaction

Absorption and Transmission

Absorption refers to the process in which incident light energy is converted into heat or atomic/molecular excitations through interactions between photons and matter. This phenomenon occurs when photons are captured by the material, leading to energy transfer that does not result in re-emission of the original light wavelength.[24] The extent of absorption is quantitatively described by the Beer-Lambert law, which states that the intensity of light, , transmitted through a material of thickness is given by where is the initial intensity and is the wavelength-dependent absorption coefficient, representing the probability of photon absorption per unit distance. This exponential decay highlights how even small values of can significantly reduce light intensity over distance.[25] Transmission, conversely, quantifies the portion of incident light that propagates through the material without being absorbed. For non-scattering media, the transmittance is defined as the ratio of transmitted intensity to incident intensity, , where is the material thickness. High transmission requires minimal absorption across the relevant spectrum.[26] At the quantum level, absorption occurs when the energy of an incident photon, (with as Planck's constant and as frequency), precisely matches the energy difference between quantized levels in the material, such as electronic orbitals or vibrational modes. This resonance condition enables the photon to excite electrons from valence to conduction bands or induce molecular vibrations, dissipating the light energy.[27] A key prerequisite for material transparency is a low absorption coefficient over the desired wavelength range, such as the visible spectrum (approximately 400–700 nm) for optical clarity, ensuring that most incident light passes through undistorted. Materials with cm in this band, like fused silica, exhibit high transparency.[28] The presence and position of absorption bands in a material's spectrum determine its colored appearance, as wavelengths not absorbed are transmitted or reflected, with complementary colors perceived by the eye; for instance, selective absorption in the red and blue regions results in a green hue.[29]Scattering and Diffusion

Scattering is an elastic process in which light photons interact with particles or inhomogeneities in a material, changing direction without energy loss. This redirection occurs through interference of the electromagnetic waves induced in the scatterer, preserving the photon's wavelength. Unlike absorption, which dissipates energy, scattering maintains the light's intensity but alters its path, contributing to the blurred transmission characteristic of translucent materials.[30] Two primary types of scattering dominate in the context of transparency and translucency. Rayleigh scattering applies to particles much smaller than the light's wavelength (typically ), where the scattered intensity is proportional to , favoring shorter wavelengths and producing effects like the blue sky. In contrast, Mie scattering governs interactions with larger particles comparable in size to the wavelength (), resulting in scattering that is largely independent of wavelength and more uniformly distributed across the spectrum.[30][31] When light undergoes multiple scattering events within a medium, the directions become randomized, leading to diffusion—a net transport resembling Brownian motion for photons. This diffusive regime is modeled by the steady-state diffusion equation: where is the light fluence, is the absorption coefficient, is the reduced scattering coefficient, is the diffusion coefficient, and is the source term; this approximation holds in highly scattering media. Diffusion blurs the light path extensively, reducing coherence and directionality compared to single scattering.[32] The impact of scattering on translucency depends on the angular distribution of scattered light. Forward scattering, prevalent in Mie regimes for particles near the wavelength size, preserves some original directionality, allowing light to penetrate deeper and maintain partial image formation, which enhances translucency. Backward scattering, however, redirects light toward the incident side, increasing opacity by minimizing transmitted intensity and promoting multiple reflections within the material.[33] Key factors influencing scattering strength include the ratio of particle radius to wavelength (), which determines the scattering regime (Rayleigh for small , Mie for larger values), and the refractive index mismatch between the particle and surrounding medium, which drives the phase shift and amplitude of the scattered wave. A larger mismatch amplifies scattering at interfaces, while matched indices minimize it, approaching transparency.[34] Representative examples illustrate these principles. In milk, fat globules with diameters around 1–10 μm cause Mie scattering of visible light (wavelength ~0.5 μm), randomizing paths and producing the material's characteristic opaque, white appearance due to uniform diffusion across wavelengths. Similarly, fog consists of water droplets (typically 5–50 μm), which induce Mie scattering, forward-peaked but multiple enough to diffuse light broadly, reducing visibility and creating a hazy, translucent veil.[35][36]Absorption Mechanisms in Solids

Electronic Transitions

Electronic transitions in solids primarily govern absorption in the ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrum, where photons excite electrons from the valence band to the conduction band across the material's bandgap. Absorption occurs when the photon energy satisfies , with representing the minimum bandgap energy required for the transition and denoting an upper energy limit beyond which other processes dominate.[37] This interband process is fundamental to optical transparency, as materials lacking suitable electronic states in the visible range (1.8–3 eV) transmit light without significant absorption.[38] In semiconductors, these electronic transitions are classified as direct or indirect based on conservation of crystal momentum. Direct transitions occur when the valence band maximum and conduction band minimum align at the same wavevector , allowing momentum conservation solely via the photon, which has negligible momentum. Indirect transitions, conversely, require phonon involvement to bridge the momentum mismatch, resulting in weaker absorption. Near the absorption edge for direct transitions under the parabolic band approximation, the absorption coefficient follows , reflecting the joint density of states.[39] This distinction influences the sharpness and intensity of the absorption onset, with direct-gap materials exhibiting stronger visible absorption if falls within that spectrum.[37] The transparency window in the visible range arises for insulators and wide-bandgap semiconductors where eV, preventing electronic excitations by visible photons. For instance, common glass has an approximate bandgap of ~5 eV, rendering it highly transparent to visible light while absorbing in the UV. Metals, lacking a bandgap due to partially filled conduction bands and free electrons, remain opaque across the visible spectrum as intraband transitions and plasma reflections dominate light interaction.[40] Exemplifying semiconductors, silicon possesses an indirect bandgap of 1.1 eV, leading to strong visible absorption and opacity despite its utility in infrared applications. Diamond, with an indirect bandgap of 5.5 eV, conversely transmits visible light effectively, contributing to its use in optical components.[41][40] Temperature influences these transitions through bandgap narrowing, primarily via thermal lattice expansion and electron-phonon coupling, which reduces and shifts the absorption edge to lower energies. This effect is more pronounced in narrower-bandgap materials, potentially encroaching on the visible range at elevated temperatures and degrading transparency.[42] For semiconductors like silicon, the bandgap decreases by approximately 0.3–0.5 meV/K, illustrating the sensitivity of optical properties to thermal conditions.[39]Vibrational Modes

In solids, vibrational modes contribute significantly to light absorption, particularly in the infrared (IR) spectrum, where photons excite vibrational and rotational modes within the molecular lattice. These modes arise from the periodic oscillations of atoms bound by chemical bonds, with absorption occurring when the photon's frequency matches the natural vibrational frequencies of these bonds. For instance, the Si-O stretching mode in silicates absorbs strongly around 1000 cm⁻¹, corresponding to mid-IR wavelengths, which contrasts with the visible transparency of many such materials where these energies are too low to interact significantly with visible light. Lattice vibrations in crystalline solids are quantized as phonons, which are collective excitations described by the solid's phonon dispersion relation. Absorption of IR photons occurs through dipole-allowed transitions, governed by selection rules that require a change in the dipole moment during the vibration; polar bonds like those in oxides or halides facilitate this process, leading to characteristic absorption bands. In non-polar materials, multi-phonon processes or impurities may enable weaker absorption. A notable phenomenon associated with these modes is the Reststrahlen bands, regions of strong reflection occurring near the phonon resonance frequencies where the absorption coefficient α is particularly high due to the material's dielectric response. These bands result from the interplay between the real and imaginary parts of the dielectric function, causing a reflectivity peak that can exceed 90% in ionic crystals like NaCl. For applications requiring IR transparency, materials with low phonon absorption are selected, such as zinc selenide (ZnSe), which exhibits minimal vibrational losses in the 0.6–20 μm range and is commonly used for IR windows and lenses. The absorption coefficient is related to the dielectric function ε(ω) by the equation: where Im[ε(ω)] captures the dissipative vibrational contributions. Examples illustrate these effects: fused silica glass remains transparent to near-IR up to about 2.5 μm but shows strong absorption in the mid-IR due to Si-O bending and stretching modes around 1100–1200 cm⁻¹; similarly, polymers display unique "fingerprint" regions in the mid-IR from C-H, C-O, and other bond vibrations, enabling spectroscopic identification but limiting their use as broad-spectrum optical materials.Transparency in Insulators

Insulators exhibit optical transparency primarily due to their large electronic bandgaps, typically exceeding 3 eV, which prevent absorption of photons in the visible spectrum by electronic transitions.[43] This wide bandgap, combined with the absence of free carriers, results in negligible free carrier absorption across the ultraviolet to near-infrared range.[44] Minimal impurities further ensure low scattering and absorption, allowing transmission from the UV to IR wavelengths provided that phonon absorption bands do not overlap significantly with the desired spectrum.[45] Point defects, such as F-centers—electron-trapped anion vacancies—can introduce localized states within the bandgap, leading to absorption tails that reduce transparency near the band edge.[46] To mitigate these effects, high-purity insulators used in optical applications require impurity levels below 1 ppm, as even trace contaminants can create defect-related absorption.[47] In contrast to conductors, insulators lack a plasma frequency in the visible range, avoiding the strong reflection predicted by the Drude model for metals, where the dielectric function is given by , with typically in the ultraviolet for metals.[28] This absence of free electron contributions enables high transmittance without metallic reflectivity. Representative examples include fused quartz (SiO₂), which maintains transparency from 0.2 to 3.5 μm due to its amorphous structure and high purity.[48] Sapphire (Al₂O₃) extends this range further, offering transmission from 0.15 to 5 μm, attributed to its wide bandgap of approximately 9 eV and robust lattice.[49] The limits of transparency in insulators are often characterized by the Urbach tail, an exponential increase in absorption coefficient near the band edge, described by where is the Urbach energy quantifying disorder-induced tailing, typically on the order of 50–100 meV in high-quality insulators.[50]Materials and Structures

Transparent Ceramics

Transparent ceramics are polycrystalline materials engineered to achieve high optical transparency through dense microstructures with fine grains and minimal porosity, typically less than 1% to minimize light scattering. Examples include aluminum oxynitride (AlON) and magnesium aluminate spinel (MgAl₂O₄), which exhibit in-line transmission exceeding 80% in the visible spectrum when fabricated with submicron grain sizes and near-theoretical density. These ceramics are produced via sintering processes that eliminate pores and control grain growth, distinguishing them from amorphous glasses or single-crystal materials by their polycrystalline nature, which allows tunable compositions while maintaining optical clarity comparable to sapphire.[51][52] Fabrication of transparent ceramics relies on advanced sintering techniques such as hot isostatic pressing (HIP) and spark plasma sintering (SPS) to achieve high density and fine microstructures. HIP applies uniform pressure and heat post-presintering to close residual pores, while SPS uses pulsed electric currents for rapid densification at lower temperatures, enabling grain sizes below 1 μm. To minimize Rayleigh scattering, which dominates light loss in polycrystalline materials, the average grain size must be significantly smaller than the wavelength of light divided by the refractive index (d << λ / 2n), often targeting submicron dimensions for visible and near-infrared transparency; for instance, grain sizes under 0.5 μm reduce boundary scattering effectively in spinel ceramics. These methods have enabled production of large-scale components with transmission >80% over thicknesses up to several millimeters.[53][54][55] Compared to traditional optical glasses, transparent ceramics offer superior mechanical properties, including higher hardness (up to 20 GPa for AlON) and enhanced resistance to thermal shock due to their polycrystalline structure, which can withstand temperature gradients exceeding 500°C without fracturing. Yttrium aluminum garnet (YAG) ceramics, for example, provide transparency from approximately 0.4 to 5 μm, making them ideal for high-power laser applications where they serve as durable gain media with efficiencies up to 9% in Nd-doped variants. These advantages stem from the ability to incorporate dopants uniformly during powder synthesis, yielding materials that combine optical performance with robustness unsuitable for glass.[56][57][58] Significant advances in transparent ceramics occurred post-2000, particularly in the development of MgAl₂O₄ spinel for armor applications through U.S. Army programs in the 2010s, which focused on nanostructured variants achieving >80% transmission and flexural strengths over 480 MPa for lightweight ballistic protection. These efforts, including DARPA-supported initiatives like manufacturing scale-up, addressed earlier limitations in porosity and grain control, enabling production of meter-scale panels with infrared transparency up to 5.5 μm for military optics. Challenges persist in non-cubic ceramics, where birefringence from anisotropic grains causes refractive index mismatches at boundaries, leading to scattering losses; this is mitigated by aligning crystallites to mimic single-crystal behavior or by extreme grain refinement to sub-100 nm scales.[59][60][61]Optical Waveguides

Optical waveguides are dielectric structures designed to confine and propagate electromagnetic waves, primarily light, with minimal loss by leveraging total internal reflection (TIR) at the interface between a core of higher refractive index and a surrounding cladding of lower refractive index.[62] The refractive index contrast, where , ensures that light incident on the core-cladding boundary at angles greater than the critical angle undergoes TIR, preventing leakage into the cladding. The critical angle is given by which defines the minimum incidence angle for TIR to occur.[63] For a mode to be guided, its propagation constant along the waveguide axis must exceed the cladding's transverse wave number, satisfying , where is the free-space wave number and is the wavelength.[64] This condition ensures the mode's field decays evanescently in the cladding while oscillating within the core, maintaining confinement.[65] Various types of optical waveguides exist, tailored to specific applications through their geometry and fabrication methods. Planar waveguides, often created via ion exchange in glass substrates, consist of a thin high-index layer sandwiched between cladding layers and support propagation in one transverse dimension. Fiber waveguides, the most prevalent type, feature a cylindrical core-cladding structure; step-index fibers have an abrupt refractive index change at the core boundary, supporting discrete modes, while graded-index fibers exhibit a gradual index profile to reduce modal dispersion. Photonic crystal waveguides, formed by periodic dielectric structures with defects, enable enhanced light control through bandgap effects, allowing guidance even in low-index cores.[66] High transparency in the core material is crucial for efficient light propagation, as it minimizes absorption and enables low attenuation coefficients, typically dB/km in telecommunications fibers to support long-distance transmission.[67] Silica-based step-index fibers exemplify this, achieving attenuation around 0.2 dB/km at 1550 nm in the third telecom window, where intrinsic material losses are minimal. Polymer waveguides, valued for their compatibility with low-cost fabrication processes like direct patterning, are widely employed in integrated optics for compact photonic circuits.[68] Recent advancements include chalcogenide glass waveguides for mid-infrared applications, demonstrating ultra-low propagation losses of 0.29 dB/m post-2020, limited primarily by material impurities.[69]Applications

Camouflage

Transparency and translucency facilitate camouflage in nature by manipulating light to reduce an organism's visibility against its background. Glass frogs (Hyalinobatrachium spp.) employ translucent skin that scatters incoming light, creating a form of edge diffusion that blurs their outline and matches the brightness of surrounding foliage, thereby providing effective predator evasion during rest.[70][71] This translucency is enhanced when the frogs aggregate their red blood cells in the liver, minimizing internal contrasts and amplifying the camouflage effect.[72] Cephalopods, including squid and octopuses, achieve dynamic camouflage through skin structures like chromatophores that adjust translucency and pigmentation in response to environmental light. These organisms rapidly switch between transparent states for open-water blending and opaque patterns for textured substrates, optimizing concealment across varying optical conditions.[73][74] Such adaptability relies on neural control of chromatophore expansion to modulate light transmission and reflection.[75] Key mechanisms underlying this camouflage include minimizing surface reflections and promoting light diffusion. Anti-reflective coatings reduce Fresnel reflections at interfaces, where reflectance is given bywith as the refractive index; this is minimized when , approaching air-like transparency to avoid detection.[76] Translucency further aids diffusion in complex environments like foliage, scattering light to soften edges and integrate the subject with vegetation without full opacity.[70] Artificial camouflage leverages these principles in military and protective applications. Transparent armor, such as sapphire laminates, combines high optical clarity with ballistic resistance, offering over 50% weight reduction compared to glass equivalents while preserving visibility for vehicle periscopes and windows.[77][78] Metamaterials enable adaptive camouflage by engineering refractive indices near 1 to match air, achieving multispectral transparency that suppresses visibility in visible and infrared regimes.[79][80] Military uses of transparent materials date to World War II, where glass periscopes on submarines allowed surface observations with minimal exposure, enhancing stealth by reducing the need to fully emerge.[81] In the 2020s, IR-transparent polymer meshes and fabrics have advanced concealment, such as multi-spectral systems using polymer composites to mask thermal signatures while maintaining visual translucency for blending in diverse terrains.[82][83] Bio-inspired adaptive materials, particularly those mimicking squid skin since 2015, incorporate artificial chromatophores in flexible sheets to generate dynamic patterns and tunable infrared reflection, allowing real-time environmental matching for enhanced concealment.[84][85] These innovations, including elastomer-based platforms with unity-order refractive index shifts, extend cephalopod-like adaptability to engineered surfaces.[86][87]

Optical Devices

Optical devices rely on transparent and translucent materials to control light propagation with precision, minimizing losses and distortions for applications in imaging, sensing, and display technologies. In lenses and optical windows, high-transparency crown glass is preferred for its low chromatic aberration, achieved through a high Abbe number typically around 59, which quantifies dispersion as , where , , and are the refractive indices at the Fraunhofer d (589 nm), F (486 nm), and C (656 nm) lines, respectively.[88][89] This formulation allows crown glass to bend wavelengths uniformly, preserving image sharpness in eyeglasses and camera objectives. Flint glass, with Abbe numbers of 50 to 55 or lower, complements crown glass in achromatic doublets by counteracting dispersion, while its high transparency ensures minimal light attenuation in protective windows for instruments like microscopes.[90] Display systems exploit translucent materials to enhance visibility and efficiency. Organic light-emitting diode (OLED) substrates often incorporate translucent polymers such as polyarylate (PAR) hybrids with nanocellulose, which maintain 85% transmittance at 600 nm and withstand temperatures above 220°C, enabling flexible, foldable screens without compromising optical clarity or thermal stability during fabrication.[91] Similarly, colorless polyimides serve as robust, translucent bases for OLEDs, supporting high mechanical flexibility while transmitting approximately 86% of visible light at 600 nm. In liquid crystal displays (LCDs), translucent diffuser sheets, typically fabricated from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) or polycarbonate (PC), scatter backlight from LEDs to deliver uniform illumination, achieving 85–92% transmission efficiency and eliminating hotspots for even panel brightness.[92][93] As of 2025, advances in transparent micro-LED displays have enabled higher resolutions and integration in foldable devices, further leveraging these materials.[94] Sensors and detectors integrate transparent conductors to facilitate light detection without obstructing incident radiation. Indium tin oxide (ITO) films, with electrical conductivity exceeding S/m and visible transmittance above 80%, form essential electrodes in photodetectors, allowing efficient charge collection while permitting high optical throughput in devices like image sensors and optical communication modules.[95] Emerging flexible transparent electronics advance this further through graphene films, which exhibit 97% transmission at 550 nm in single-layer configurations, supporting bendable circuits and wearables with superior optical-electrical balance. Post-2015 innovations in perovskite solar cells have introduced translucent electrodes via optimized metal oxide buffers, yielding semi-transparent devices with 21.68% efficiency and over 99% retention after 240 hours of operation, ideal for tandem photovoltaics and building-integrated sensors.[96][97] Evaluating transparent conductors involves metrics that trade off electrical and optical performance. A key figure of merit, , divides the electrical conductivity by the visible absorption coefficient , providing a scale for material efficacy in devices; for example, fluorine-doped zinc oxide achieves , highlighting its suitability for high-throughput applications like displays and sensors.[98] As of 2025, transparent conductors have reached sheet resistances as low as 26 Ω/sq, improving efficiency in flexible electronics.[99]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/diaphanous