Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Electromagnetic spectrum

View on Wikipedia

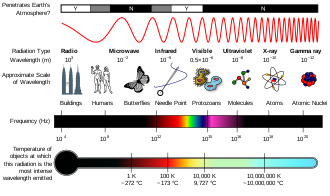

The electromagnetic spectrum is the full range of electromagnetic radiation, organized by frequency or wavelength. The spectrum is divided into separate bands, with different names for the electromagnetic waves within each band. From low to high frequency these are: radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visible light, ultraviolet, X-rays, and gamma rays. The electromagnetic waves in each of these bands have different characteristics, such as how they are produced, how they interact with matter, and their practical applications.

Radio waves, at the low-frequency end of the spectrum, have the lowest photon energy and the longest wavelengths—thousands of kilometers, or more. They can be emitted and received by antennas, and pass through the atmosphere, foliage, and most building materials.

Gamma rays, at the high-frequency end of the spectrum, have the highest photon energies and the shortest wavelengths—much smaller than an atomic nucleus. Gamma rays, X-rays, and extreme ultraviolet rays are called ionizing radiation because their high photon energy is able to ionize atoms, causing chemical reactions. Longer-wavelength radiation such as visible light is nonionizing; the photons do not have sufficient energy to ionize atoms.

Throughout most of the electromagnetic spectrum, spectroscopy can be used to separate waves of different frequencies, so that the intensity of the radiation can be measured as a function of frequency or wavelength. Spectroscopy is used to study the interactions of electromagnetic waves with matter.[1]

History and discovery

[edit]

Humans have always been aware of visible light and radiant heat but for most of history it was not known that these phenomena were connected or were representatives of a more extensive principle. The ancient Greeks recognized that light traveled in straight lines and studied some of its properties, including reflection and refraction. Light was intensively studied from the beginning of the 17th century leading to the invention of important instruments like the telescope and microscope. Isaac Newton was the first to use the term spectrum for the range of colours that white light could be split into with a prism. Starting in 1666, Newton showed that these colours were intrinsic to light and could be recombined into white light. A debate arose over whether light had a wave nature or a particle nature with René Descartes, Robert Hooke and Christiaan Huygens favouring a wave description and Newton favouring a particle description. Huygens in particular had a well developed theory from which he was able to derive the laws of reflection and refraction. Around 1801, Thomas Young measured the wavelength of a light beam with his two-slit experiment thus conclusively demonstrating that light was a wave.

In 1800, William Herschel discovered infrared radiation.[2] He was studying the temperature of different colours by moving a thermometer through light split by a prism. He noticed that the highest temperature was beyond red. He theorized that this temperature change was due to "calorific rays", a type of light ray that could not be seen. The next year, Johann Ritter, working at the other end of the spectrum, noticed what he called "chemical rays" (invisible light rays that induced certain chemical reactions). These behaved similarly to visible violet light rays, but were beyond them in the spectrum.[3] They were later renamed ultraviolet radiation.

The study of electromagnetism began in 1820 when Hans Christian Ørsted discovered that electric currents produce magnetic fields (Oersted's law). Light was first linked to electromagnetism in 1845, when Michael Faraday noticed that the polarization of light traveling through a transparent material responded to a magnetic field (see Faraday effect). During the 1860s, James Clerk Maxwell developed four partial differential equations (Maxwell's equations) for the electromagnetic field. Two of these equations predicted the possibility and behavior of waves in the field. Analyzing the speed of these theoretical waves, Maxwell realized that they must travel at a speed that was about the known speed of light. This startling coincidence in value led Maxwell to make the inference that light itself is a type of electromagnetic wave. Maxwell's equations predicted an infinite range of frequencies of electromagnetic waves, all traveling at the speed of light. This was the first indication of the existence of the entire electromagnetic spectrum.

Maxwell's predicted waves included waves at very low frequencies compared to infrared, which in theory might be created by oscillating charges in an ordinary electrical circuit of a certain type. Attempting to prove Maxwell's equations and detect such low frequency electromagnetic radiation, in 1886, the physicist Heinrich Hertz built an apparatus to generate and detect what are now called radio waves. Hertz found the waves and was able to infer (by measuring their wavelength and multiplying it by their frequency) that they traveled at the speed of light. Hertz also demonstrated that the new radiation could be both reflected and refracted by various dielectric media, in the same manner as light. For example, Hertz was able to focus the waves using a lens made of tree resin. In a later experiment, Hertz similarly produced and measured the properties of microwaves. These new types of waves paved the way for inventions such as the wireless telegraph and the radio.

In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen noticed a new type of radiation emitted during an experiment with an evacuated tube subjected to a high voltage. He called this radiation "x-rays" and found that they were able to travel through parts of the human body but were reflected or stopped by denser matter such as bones. Before long, many uses were found for this radiography.

The last portion of the electromagnetic spectrum was filled in with the discovery of gamma rays. In 1900, Paul Villard was studying the radioactive emissions of radium when he identified a new type of radiation that he at first thought consisted of particles similar to known alpha and beta particles, but with the power of being far more penetrating than either. However, in 1910, British physicist William Henry Bragg demonstrated that gamma rays are electromagnetic radiation, not particles, and in 1914, Ernest Rutherford (who had named them gamma rays in 1903 when he realized that they were fundamentally different from charged alpha and beta particles) and Edward Andrade measured their wavelengths, and found that gamma rays were similar to X-rays, but with shorter wavelengths.

The wave-particle debate was rekindled in 1901 when Max Planck discovered that light is absorbed only in discrete "quanta", now called photons, implying that light has a particle nature. This idea was made explicit by Albert Einstein in 1905, but never accepted by Planck and many other contemporaries. The modern position of science is that electromagnetic radiation has both a wave and a particle nature, the wave-particle duality. The contradictions arising from this position are still being debated by scientists and philosophers.

Range

[edit]Electromagnetic waves are typically described by any of the following three physical properties: the frequency f, wavelength λ, or photon energy E. Frequencies observed in astronomy range from 2.4×1023 Hz (1 GeV gamma rays) down to the local plasma frequency of the ionized interstellar medium (~1 kHz). Wavelength is inversely proportional to the wave frequency,[1] so gamma rays have very short wavelengths that are fractions of the size of atoms, whereas wavelengths on the opposite end of the spectrum can be indefinitely long. Photon energy is directly proportional to the wave frequency, so gamma ray photons have the highest energy (around a billion electron volts), while radio wave photons have very low energy (around a femtoelectronvolt). These relations are illustrated by the following equations:

where:

- c is the speed of light in vacuum

- h is the Planck constant.

Whenever electromagnetic waves travel in a medium with matter, their wavelength is decreased. Wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation, whatever medium they are traveling through, are usually quoted in terms of the vacuum wavelength, although this is not always explicitly stated.

Generally, electromagnetic radiation is classified by wavelength into radio wave, microwave, infrared, visible light, ultraviolet, X-rays and gamma rays. The behavior of EM radiation depends on its wavelength. When EM radiation interacts with single atoms and molecules, its behavior also depends on the amount of energy per quantum (photon) it carries.

Spectroscopy can detect a much wider region of the EM spectrum than the visible wavelength range of 400 nm to 700 nm in a vacuum. A common laboratory spectroscope can detect wavelengths from 2 nm to 2500 nm.[1] Detailed information about the physical properties of objects, gases, or even stars can be obtained from this type of device. Spectroscopes are widely used in astrophysics. For example, many hydrogen atoms emit a radio wave photon that has a wavelength of 21.12 cm. Also, frequencies of 30 Hz and below can be produced by and are important in the study of certain stellar nebulae[4] and frequencies as high as 2.9×1027 Hz have been detected from astrophysical sources.[5]

Regions

[edit]

The types of electromagnetic radiation are broadly classified into the following classes (regions, bands or types):[1]

- Gamma radiation

- X-ray radiation

- Ultraviolet radiation

- Visible light (light that humans can see)

- Infrared radiation

- Microwave radiation

- Radio waves

This classification goes in the increasing order of wavelength, which is characteristic of the type of radiation.[1]

There are no precisely defined boundaries between the bands of the electromagnetic spectrum; rather they fade into each other like the bands in a rainbow. Radiation of each frequency and wavelength (or in each band) has a mix of properties of the two regions of the spectrum that bound it. For example, red light resembles infrared radiation, in that it can excite and add energy to some chemical bonds and indeed must do so to power the chemical mechanisms responsible for photosynthesis and the working of the visual system.

In atomic and nuclear physics, the distinction between X-rays and gamma rays is based on sources: the photons generated from nuclear decay or other nuclear and subnuclear/particle process are termed gamma rays, whereas X-rays are generated by electronic transitions involving energetically deep inner atomic electrons.[6][7] Electronic transitions in muonic atoms transitions are also said to produce X-rays.[8] In astrophysics, energies below 100keV are called X-rays and higher energies are gamma rays.[9]

The region of the spectrum where electromagnetic radiation is observed may differ from the region it was emitted in due to relative velocity of the source and observer, (the Doppler shift), relative gravitational potential (gravitational redshift), or expansion of the universe (cosmological redshift).[9]: 543 For example, the cosmic microwave background, relic blackbody radiation from the era of recombination, started out at energies around 1eV, but as has undergone enough cosmological red shift to put it into the microwave region of the spectrum for observers on Earth.[10]

| Class | Wave- length |

Freq- uency |

Energy per photon | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizing radiation |

γ | Gamma rays | 10 pm | 30 EHz | 124 keV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100 pm | 3 EHz | 12.4 keV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HX | Hard X-rays | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SX | Soft X-rays | 10 nm | 30 PHz | 124 eV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EUV | Extreme ultraviolet |

121 nm | 3 PHz | 10.2 eV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| NUV | Near ultraviolet |

400 nm | 750 THz | 3.1 eV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Visible spectrum | 700 nm | 480 THz | 1.77 eV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Infrared | NIR | Near infrared | 1 μm | 300 THz | 1.24 eV | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 μm | 30 THz | 124 meV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MIR | Mid infrared | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100 μm | 3 THz | 12.4 meV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| FIR | Far infrared | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 mm | 300 GHz | 1.24 meV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Micro- waves[11] |

EHF | Extremely high frequency | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 cm | 30 GHz | 124 μeV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SHF | Super high frequency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 dm | 3 GHz | 12.4 μeV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UHF | Ultra high frequency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 m | 300 MHz | 1.24 μeV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Radio waves[11] |

VHF | Very high frequency | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 m | 30 MHz | 124 neV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HF | High frequency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100 m | 3 MHz | 12.4 neV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MF | Medium frequency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 km | 300 kHz | 1.24 neV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LF | Low frequency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 km | 30 kHz | 124 peV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| VLF | Very low frequency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100 km | 3 kHz | 12.4 peV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Band 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 Mm | 300 Hz | 1.24 peV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Band 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 Mm | 30 Hz | 124 feV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | Band 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100 Mm | 3 Hz | 12.4 feV | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sources[12][13][14] Table shows the lower frequency limits (and higher wavelength limits) for the specified class

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rationale for names

[edit]Electromagnetic radiation interacts with matter in different ways across the spectrum. These types of interaction are so different that historically different names have been applied to different parts of the spectrum, as though these were different types of radiation. Thus, although these "different kinds" of electromagnetic radiation form a quantitatively continuous spectrum of frequencies and wavelengths, the spectrum remains divided for practical reasons arising from these qualitative interaction differences.

| Region of the spectrum | Main interactions with matter |

|---|---|

| Radio | Collective oscillation of charge carriers in bulk material (plasma oscillation). An example would be the oscillatory travels of the electrons in an antenna. |

| Microwave through far infrared | Plasma oscillation, molecular rotation |

| Near infrared | Molecular vibration, plasma oscillation (in metals only) |

| Visible | Molecular electron excitation (including pigment molecules found in the human retina), plasma oscillations (in metals only) |

| Ultraviolet | Excitation of molecular and atomic valence electrons, including ejection of the electrons (photoelectric effect) |

| X-rays | Excitation and ejection of core atomic electrons, Compton scattering (for low atomic numbers) |

| Gamma rays | Energetic ejection of core electrons in heavy elements, Compton scattering (for all atomic numbers), excitation of atomic nuclei, including dissociation of nuclei |

| High-energy gamma rays | Creation of particle-antiparticle pairs. At very high energies a single photon can create a shower of high-energy particles and antiparticles upon interaction with matter. |

Types of radiation

[edit]Radio waves

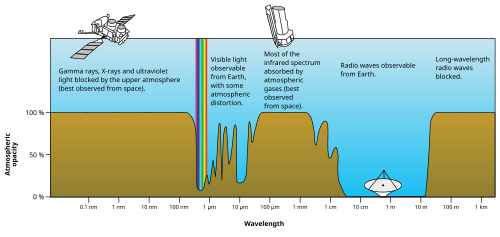

[edit]Radio waves are emitted and received by antennas, which consist of conductors such as metal rod resonators. In artificial generation of radio waves, an electronic device called a transmitter generates an alternating electric current which is applied to an antenna. The oscillating electrons in the antenna generate oscillating electric and magnetic fields that radiate away from the antenna as radio waves. In reception of radio waves, the oscillating electric and magnetic fields of a radio wave couple to the electrons in an antenna, pushing them back and forth, creating oscillating currents which are applied to a radio receiver. Earth's atmosphere is mainly transparent to radio waves, except for layers of charged particles in the ionosphere which can reflect certain frequencies.

Radio waves are extremely widely used to transmit information across distances in radio communication systems such as radio broadcasting, television, two way radios, mobile phones, communication satellites, and wireless networking. In a radio communication system, a radio frequency current is modulated with an information-bearing signal in a transmitter by varying either the amplitude, frequency or phase, and applied to an antenna. The radio waves carry the information across space to a receiver, where they are received by an antenna and the information extracted by demodulation in the receiver. Radio waves are also used for navigation in systems like Global Positioning System (GPS) and navigational beacons, and locating distant objects in radiolocation and radar. They are also used for remote control, and for industrial heating.

The use of the radio spectrum is strictly regulated by governments, coordinated by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) which allocates frequencies to different users for different uses.

Microwaves

[edit]

Microwaves are radio waves of short wavelength, from about 10 centimeters to one millimeter, in the SHF and EHF frequency bands. Microwave energy is produced with klystron and magnetron tubes, and with solid state devices such as Gunn and IMPATT diodes. Although they are emitted and absorbed by short antennas, they are also absorbed by polar molecules, coupling to vibrational and rotational modes, resulting in bulk heating. Unlike higher frequency waves such as infrared and visible light which are absorbed mainly at surfaces, microwaves can penetrate into materials and deposit their energy below the surface. This effect is used to heat food in microwave ovens, and for industrial heating and medical diathermy. Microwaves are the main wavelengths used in radar, and are used for satellite communication, and wireless networking technologies such as Wi-Fi. The copper cables (transmission lines) which are used to carry lower-frequency radio waves to antennas have excessive power losses at microwave frequencies, and metal pipes called waveguides are used to carry them. Although at the low end of the band the atmosphere is mainly transparent, at the upper end of the band absorption of microwaves by atmospheric gases limits practical propagation distances to a few kilometers.

Terahertz radiation or sub-millimeter radiation is a region of the spectrum from about 100 GHz to 30 terahertz (THz) between microwaves and far infrared which can be regarded as belonging to either band. Until recently, the range was rarely studied and few sources existed for microwave energy in the so-called terahertz gap, but applications such as imaging and communications are now appearing. Scientists are also looking to apply terahertz technology in the armed forces, where high-frequency waves might be directed at enemy troops to incapacitate their electronic equipment.[15] Terahertz radiation is strongly absorbed by atmospheric gases, making this frequency range useless for long-distance communication.

Infrared radiation

[edit]The infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum covers the range from roughly 300 GHz to 400 THz (1 mm – 750 nm). It can be divided into three parts:[1]

- Far-infrared, from 300 GHz to 30 THz (1 mm – 10 μm). The lower part of this range may also be called microwaves or terahertz waves. This radiation is typically absorbed by so-called rotational modes in gas-phase molecules, by molecular motions in liquids, and by phonons in solids. The water in Earth's atmosphere absorbs so strongly in this range that it renders the atmosphere in effect opaque. However, there are certain wavelength ranges ("windows") within the opaque range that allow partial transmission, and can be used for astronomy. The wavelength range from approximately 200 μm up to a few mm is often referred to as Submillimetre astronomy, reserving far infrared for wavelengths below 200 μm.

- Mid-infrared, from 30 THz to 120 THz (10–2.5 μm). Hot objects (black-body radiators) can radiate strongly in this range, and human skin at normal body temperature radiates strongly at the lower end of this region. This radiation is absorbed by molecular vibrations, where the different atoms in a molecule vibrate around their equilibrium positions. This range is sometimes called the fingerprint region, since the mid-infrared absorption spectrum of a compound is very specific for that compound.

- Near-infrared, from 120 THz to 400 THz (2,500–750 nm). Physical processes that are relevant for this range are similar to those for visible light. The highest frequencies in this region can be detected directly by some types of photographic film, and by many types of solid state image sensors for infrared photography and videography.

Visible light

[edit] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Colour | Wavelength (nm) |

Frequency (THz) |

Photon energy (eV) |

| 380–450 | 670–790 | 2.75–3.26 | |

| 450–485 | 620–670 | 2.56–2.75 | |

| 485–500 | 600–620 | 2.48–2.56 | |

| 500–565 | 530–600 | 2.19–2.48 | |

| 565–590 | 510–530 | 2.10–2.19 | |

| 590–625 | 480–510 | 1.98–2.10 | |

| 625–750 | 400–480 | 1.65–1.98 | |

Above infrared in frequency comes visible light. The Sun emits its peak power in the visible region, although integrating the entire emission power spectrum through all wavelengths shows that the Sun emits slightly more infrared than visible light.[16] By definition, visible light is the part of the EM spectrum the human eye is the most sensitive to. Visible light (and near-infrared light) is typically absorbed and emitted by electrons in molecules and atoms that move from one energy level to another. This action allows the chemical mechanisms that underlie human vision and plant photosynthesis. The light that excites the human visual system is a very small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. A rainbow shows the optical (visible) part of the electromagnetic spectrum; infrared (if it could be seen) would be located just beyond the red side of the rainbow whilst ultraviolet would appear just beyond the opposite violet end.

Electromagnetic radiation with a wavelength between 380 nm and 760 nm (400–790 terahertz) is detected by the human eye and perceived as visible light. Other wavelengths, especially near infrared (longer than 760 nm) and ultraviolet (shorter than 380 nm) are also sometimes referred to as light, especially when the visibility to humans is not relevant. White light is a combination of lights of different wavelengths in the visible spectrum. Passing white light through a prism splits it up into the several colours of light observed in the visible spectrum between 400 nm and 780 nm.

If radiation having a frequency in the visible region of the EM spectrum reflects off an object, say, a bowl of fruit, and then strikes the eyes, this results in visual perception of the scene. The brain's visual system processes the multitude of reflected frequencies into different shades and hues, and through this insufficiently understood psychophysical phenomenon, most people perceive a bowl of fruit.

At most wavelengths, however, the information carried by electromagnetic radiation is not directly detected by human senses. Natural sources produce EM radiation across the spectrum, and technology can also manipulate a broad range of wavelengths. Optical fiber transmits light that, although not necessarily in the visible part of the spectrum (it is usually infrared), can carry information. The modulation is similar to that used with radio waves.

Ultraviolet radiation

[edit]

Next in frequency comes ultraviolet (UV). In frequency (and thus energy), UV rays sit between the violet end of the visible spectrum and the X-ray range. The UV wavelength spectrum ranges from 399 nm to 10 nm and is divided into 3 sections: UVA, UVB, and UVC.

UV is the lowest energy range energetic enough to ionize atoms, separating electrons from them, and thus causing chemical reactions. UV, X-rays, and gamma rays are thus collectively called ionizing radiation; exposure to them can damage living tissue. UV can also cause substances to glow with visible light; this is called fluorescence. UV fluorescence is used by forensics to detect any evidence like blood and urine, that is produced by a crime scene. Also UV fluorescence is used to detect counterfeit money and IDs, as they are laced with material that can glow under UV.

At the middle range of UV, UV rays cannot ionize but can break chemical bonds, making molecules unusually reactive. Sunburn, for example, is caused by the disruptive effects of middle range UV radiation on skin cells, which is the main cause of skin cancer. UV rays in the middle range can irreparably damage the complex DNA molecules in the cells producing thymine dimers making it a very potent mutagen. Due to skin cancer caused by UV, the sunscreen industry was invented to combat UV damage. Mid UV wavelengths are called UVB and UVB lights such as germicidal lamps are used to kill germs and also to sterilize water.

The Sun emits UV radiation (about 10% of its total power), including extremely short wavelength UV that could potentially destroy most life on land (ocean water would provide some protection for life there). However, most of the Sun's damaging UV wavelengths are absorbed by the atmosphere before they reach the surface. The higher energy (shortest wavelength) ranges of UV (called "vacuum UV") are absorbed by nitrogen and, at longer wavelengths, by simple diatomic oxygen in the air. Most of the UV in the mid-range of energy is blocked by the ozone layer, which absorbs strongly in the important 200–315 nm range, the lower energy part of which is too long for ordinary dioxygen in air to absorb. This leaves less than 3% of sunlight at sea level in UV, with all of this remainder at the lower energies. The remainder is UV-A, along with some UV-B. The very lowest energy range of UV between 315 nm and visible light (called UV-A) is not blocked well by the atmosphere, but does not cause sunburn and does less biological damage. However, it is not harmless and does create oxygen radicals, mutations and skin damage.

X-rays

[edit]After UV come X-rays, which, like the upper ranges of UV are also ionizing. However, due to their higher energies, X-rays can also interact with matter by means of the Compton effect. Hard X-rays have shorter wavelengths than soft X-rays and as they can pass through many substances with little absorption, they can be used to 'see through' objects with 'thicknesses' less than that equivalent to a few meters of water. One notable use is diagnostic X-ray imaging in medicine (a process known as radiography). X-rays are useful as probes in high-energy physics. In astronomy, the accretion disks around neutron stars and black holes emit X-rays, enabling studies of these phenomena. X-rays are also emitted by stellar corona and are strongly emitted by some types of nebulae. However, X-ray telescopes must be placed outside the Earth's atmosphere to see astronomical X-rays, since the great depth of the atmosphere of Earth is opaque to X-rays (with areal density of 1000 g/cm2), equivalent to 10 meters thickness of water.[17] This is an amount sufficient to block almost all astronomical X-rays (and also astronomical gamma rays—see below).

Gamma rays

[edit]After hard X-rays come gamma rays, which were discovered by Paul Ulrich Villard in 1900. These are the most energetic photons, having no defined lower limit to their wavelength. In astronomy they are valuable for studying high-energy objects or regions, however as with X-rays this can only be done with telescopes outside the Earth's atmosphere. Gamma rays are used experimentally by physicists for their penetrating ability and are produced by a number of radioisotopes. They are used for irradiation of foods and seeds for sterilization, and in medicine they are occasionally used in radiation cancer therapy.[18] More commonly, gamma rays are used for diagnostic imaging in nuclear medicine, an example being PET scans. The wavelength of gamma rays can be measured with high accuracy through the effects of Compton scattering.

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Mehta, Akul (25 August 2011). "Introduction to the Electromagnetic Spectrum and Spectroscopy". Pharmaxchange.info. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

- ^ "Herschel Discovers Infrared Light". Cool Cosmos Classroom activities. Archived from the original on 2012-02-25. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

He directed sunlight through a glass prism to create a spectrum [...] and then measured the temperature of each colour. [...] He found that the temperatures of the colours increased from the violet to the red part of the spectrum. [...] Herschel decided to measure the temperature just beyond the red of the spectrum in a region where no sunlight was visible. To his surprise, he found that this region had the highest temperature of all.

- ^ Davidson, Michael W. "Johann Wilhelm Ritter (1776–1810)". The Florida State University. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

Ritter [...] hypothesized that there must also be invisible radiation beyond the violet end of the spectrum and commenced experiments to confirm his speculation. He began working with silver chloride, a substance decomposed by light, measuring the speed at which different colours of light broke it down. [...] Ritter [...] demonstrated that the fastest rate of decomposition occurred with radiation that could not be seen, but that existed in a region beyond the violet. Ritter initially referred to the new type of radiation as chemical rays, but the title of ultraviolet radiation eventually became the preferred term.

- ^ Condon, J. J.; Ransom, S. M. "Essential Radio Astronomy: Pulsar Properties". National Radio Astronomy Observatory. Archived from the original on 2011-05-04. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ^ Abdo, A. A.; Allen, B.; Berley, D.; Blaufuss, E.; Casanova, S.; Chen, C.; Coyne, D. G.; Delay, R. S.; Dingus, B. L.; Ellsworth, R. W.; Fleysher, L.; Fleysher, R.; Gebauer, I.; Gonzalez, M. M.; Goodman, J. A.; Hays, E.; Hoffman, C. M.; Kolterman, B. E.; Kelley, L. A.; Lansdell, C. P.; Linnemann, J. T.; McEnery, J. E.; Mincer, A. I.; Moskalenko, I. V.; Nemethy, P.; Noyes, D.; Ryan, J. M.; Samuelson, F. W.; Saz Parkinson, P. M.; et al. (2007). "Discovery of TeV Gamma-Ray Emission from the Cygnus Region of the Galaxy". The Astrophysical Journal. 658 (1): L33 – L36. arXiv:astro-ph/0611691. Bibcode:2007ApJ...658L..33A. doi:10.1086/513696. S2CID 17886934.

- ^

Feynman, Richard; Leighton, Robert; Sands, Matthew (1963). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol.1. US: Addison-Wesley. pp. 2–5. ISBN 978-0-201-02116-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ L'Annunziata, Michael; Baradei, Mohammad (2003). Handbook of Radioactivity Analysis. Academic Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-12-436603-9.

- ^ Corrections to muonic X-rays and a possible proton halo Archived 2017-03-13 at the Wayback Machine slac-pub-0335 (1967)

- ^ a b Grupen, Claus; Cowan, G.; Eidelman, S. D.; Stroh, T. (2005). Astroparticle Physics. Springer. p. 109. ISBN 978-3-540-25312-9.

- ^ Samtleben, Dorothea; Staggs, Suzanne; Winstein, Bruce (2007-11-01). "The Cosmic Microwave Background for Pedestrians: A Review for Particle and Nuclear Physicists". Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science. 57 (1): 245–283. arXiv:0803.0834. Bibcode:2007ARNPS..57..245S. doi:10.1146/annurev.nucl.54.070103.181232. ISSN 0163-8998.

- ^ a b Article 2 "Final Acts WRC-15: World Radiocommunication Conference", International Telecommunication Union Geneva, 2015

- ^ What is Light? Archived December 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine – UC Davis lecture slides

- ^ Elert, Glenn. "The Electromagnetic Spectrum". The Physics Hypertextbook. Archived from the original on 2022-01-21. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ Stimac, Tomislav. "Definition of frequency bands (VLF, ELF... etc.)". vlf.it. Archived from the original on 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2022-01-21.

- ^ "Advanced weapon systems using lethal Short-pulse terahertz radiation from high-intensity-laser-produced plasmas". India Daily. March 6, 2005. Archived from the original on 6 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ^ "Reference Solar Spectral Irradiance: Air Mass 1.5". Archived from the original on 2019-05-12. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- ^ Koontz, Steve (26 June 2012) Designing Spacecraft and Mission Operations Plans to Meet Flight Crew Radiation Dose Archived 2017-05-02 at the Wayback Machine. NASA/MIT Workshop. See pages I-7 (atmosphere) and I-23 (for water).

- ^ Uses of Electromagnetic Waves | gcse-revision, physics, waves, uses-electromagnetic-waves | Revision World

External links

[edit]- Australian Radiofrequency Spectrum Allocations Chart (from Australian Communications and Media Authority)

- Canadian Table of Frequency Allocations Archived 2008-12-09 at the Wayback Machine (from Industry Canada)

- U.S. Frequency Allocation Chart – Covering the range 3 kHz to 300 GHz (from Department of Commerce)

- UK frequency allocation table (from Ofcom, which inherited the Radiocommunications Agency's duties, pdf format)

- Flash EM Spectrum Presentation / Tool – Very complete and customizable.

- Poster "Electromagnetic Radiation Spectrum" (992 kB)

Electromagnetic spectrum

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Electromagnetic Waves

Nature and Propagation of Electromagnetic Waves

Electromagnetic waves are self-propagating transverse waves composed of oscillating electric and magnetic fields that are perpendicular to each other and to the direction of propagation./University_Physics_II_-Thermodynamics_Electricity_and_Magnetism(OpenStax)/16%3A_Electromagnetic_Waves/16.02%3A_Maxwells_Equations_and_Electromagnetic_Waves) The electric field and magnetic field vary sinusoidally in phase, with their mutual perpendicularity ensuring that the wave's energy transport occurs along the propagation axis without requiring a material medium.[2] This transverse nature distinguishes electromagnetic waves from longitudinal mechanical waves, such as sound, which rely on particle displacement parallel to the propagation direction and necessitate a medium for transmission./University_Physics_II_-Thermodynamics_Electricity_and_Magnetism(OpenStax)/16%3A_Electromagnetic_Waves/16.01%3A_The_Production_of_Electromagnetic_Waves) In vacuum, electromagnetic waves propagate at the constant speed of light, m/s, which serves as a fundamental physical constant and the maximum speed for information transfer in the universe.[9] This velocity arises from the interplay of electric permittivity and magnetic permeability of free space, where ./University_Physics_II_-Thermodynamics_Electricity_and_Magnetism(OpenStax)/16%3A_Electromagnetic_Waves/16.02%3A_Maxwells_Equations_and_Electromagnetic_Waves) Unlike mechanical waves, electromagnetic waves do not diminish in speed due to the absence of a medium, allowing them to traverse interstellar distances with minimal attenuation in empty space.[2] The theoretical foundation for electromagnetic waves is provided by Maxwell's equations, a set of four coupled differential equations that unify electricity, magnetism, and optics.[10] In their differential form for vacuum (where current density ), they are: These equations predict wave solutions where changing electric fields induce magnetic fields and vice versa, enabling self-sustaining propagation.[11] Taking the curl of Faraday's law () and substituting Ampère's law with Maxwell's correction yields the wave equation , confirming the wavelike behavior./University_Physics_II_-Thermodynamics_Electricity_and_Magnetism(OpenStax)/16%3A_Electromagnetic_Waves/16.02%3A_Maxwells_Equations_and_Electromagnetic_Waves) When electromagnetic waves interact with matter, they exhibit behaviors such as reflection, refraction, diffraction, and polarization, governed by the material's dielectric properties and boundaries.[12] Reflection occurs at interfaces where the wave bounces off, with the angle of incidence equaling the angle of reflection, as described by Fresnel equations./06%3A_An_Introduction_to_Spectrophotometric_Methods/6.02%3A_Wave_Properties_of_Electromagnetic_Radiation) Refraction involves bending upon entering a medium with different refractive index , where is the wave speed in the material, following Snell's law .[13] Diffraction allows waves to bend around obstacles or through apertures, revealing their wave nature beyond geometric optics, while polarization refers to the orientation of the electric field vector, which can be linear, circular, or elliptical, and is altered by interactions with anisotropic media or polarizers.[12] These phenomena enable applications from optical instruments to wireless communication./University_Physics_II_-Thermodynamics_Electricity_and_Magnetism(OpenStax)/16%3A_Electromagnetic_Waves/16.01%3A_The_Production_of_Electromagnetic_Waves)Key Characteristics: Wavelength, Frequency, and Energy

The electromagnetic spectrum encompasses waves distinguished by two primary characteristics: wavelength and frequency. Wavelength, denoted as , represents the spatial distance between consecutive crests (or troughs) of the wave, typically measured in units ranging from meters for long radio waves to nanometers or angstroms ($1= 10^{-10}f3 \times 10^43 \times 10^{19}$ Hz for gamma rays.[3]/Spectroscopy/Fundamentals_of_Spectroscopy/Electromagnetic_Radiation) These properties are fundamentally interrelated through the wave equation derived from Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism, which states that the speed of electromagnetic waves in vacuum, , equals the product of frequency and wavelength: .[14] Here, is a universal constant with the exact value $299792458c10^{-12}10^{19}$ Hz).[3] A third key characteristic is the energy associated with electromagnetic radiation, particularly when viewed through the quantum lens where light behaves as discrete packets called photons. The energy of a single photon is given by , where is Planck's constant, with the exact value J s.[15] This formula, introduced by Einstein to explain the photoelectric effect, highlights the quantum nature of electromagnetic waves: higher-frequency photons carry more energy, enabling phenomena like ionization in the ultraviolet and gamma-ray regions, whereas lower-frequency photons, such as those in radio waves, have minimal individual energy but can accumulate through many photons. The electromagnetic spectrum thus forms a continuous progression ordered by increasing frequency (and energy) from radio waves to gamma rays, with no abrupt boundaries but rather a seamless transition governed by these interrelated properties.[16]Historical Development

Theoretical Foundations

The foundations of electromagnetic theory emerged in the early 19th century, beginning with Hans Christian Ørsted's 1820 discovery that an electric current flowing through a wire produces a magnetic field around it, thereby establishing a direct link between electricity and magnetism.[17] This observation, reported in Ørsted's pamphlet Experimenta circa effectum conflictus electrici in acum magneticam, demonstrated that the magnetic effect circled the current in a manner consistent with the right-hand rule, overturning the prior view of electricity and magnetism as separate phenomena.[18] Building on Ørsted's work, Michael Faraday conducted experiments in 1831 that revealed electromagnetic induction, showing that a changing magnetic field near a conductor induces an electric current within it.[19] Faraday's investigations, detailed in his paper "On the Induction of Electric Currents," involved moving magnets relative to coils or varying currents to produce induced electromotive forces, and he conceptualized these effects through the notion of continuous "lines of force" or fields permeating space, rather than relying solely on action-at-a-distance.[20] This field concept provided a qualitative framework for understanding how magnetic fields could influence electric charges without physical contact, paving the way for a unified theory. The culmination of these ideas came in James Clerk Maxwell's 1865 paper, "A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field," which mathematically synthesized electricity, magnetism, and optics into a coherent framework.[21] Maxwell modified Ampère's circuital law by introducing the "displacement current" term, representing the rate of change of electric displacement in regions without conduction current, such as between capacitor plates; this addition ensured the continuity of current in circuits and enabled the propagation of electromagnetic disturbances as waves.[22] From his equations, Maxwell derived that these waves travel through space at a speed equal to that of light, approximately 3 × 10^8 meters per second in vacuum, leading him to conclude that light itself is an electromagnetic wave, thereby resolving the longstanding divide between optical phenomena and electrical-magnetic interactions.[23] This theoretical prediction was later experimentally verified by Heinrich Hertz in 1887 through the generation and detection of radio waves.[24]Experimental Discoveries

Prior to the unification of electromagnetic theory, experimental extensions of the visible spectrum had already revealed invisible regions. In 1800, British astronomer William Herschel discovered infrared radiation by passing sunlight through a prism and measuring temperatures with thermometers placed beyond the red end of the visible spectrum, finding higher heat in the invisible region, indicating longer-wavelength radiation associated with thermal energy.[25] In 1801, German physicist Johann Wilhelm Ritter identified ultraviolet radiation by observing that silver chloride paper blackened more rapidly beyond the violet end of the spectrum when exposed to sunlight dispersed by a prism, demonstrating shorter-wavelength, chemically active rays invisible to the eye.[26] These discoveries expanded the known optical spectrum and anticipated the broader electromagnetic nature of light. In 1887, Heinrich Hertz conducted pioneering experiments that experimentally verified the existence of electromagnetic waves predicted by James Clerk Maxwell's theory. Using a spark-gap transmitter consisting of an induction coil connected to a dipole antenna with a small gap, Hertz generated high-frequency oscillations, producing radio waves with wavelengths around 66 cm. He detected these waves with a simple loop receiver equipped with another spark gap, observing that the induced sparks confirmed the waves' propagation through space. Further tests demonstrated that these waves exhibited reflection from metal sheets and diffraction around obstacles, behaviors analogous to those of visible light, thus establishing radio waves as part of the electromagnetic spectrum.[27] Building on Hertz's findings, Oliver Lodge demonstrated practical transmission and detection of electromagnetic waves in 1894 during a lecture at the Royal Institution, using a coherer detector to receive signals over distances of about 150 meters and showcasing synthetic Hertzian waves for signaling purposes. In the mid-1890s, Guglielmo Marconi advanced this work by developing wireless telegraphy systems, filing a provisional patent in 1896 for a device that transmitted Morse code signals using spark transmitters and coherers, achieving ranges up to several kilometers by 1897 and extending operations to longer wavelengths for improved reliability over land and sea. These efforts marked the initial practical exploitation of radio waves, bridging laboratory demonstrations to communication applications.[28][29] In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays while investigating cathode rays in a vacuum tube, observing that when high-voltage electrons struck a glass wall or metal target, an unknown penetrating radiation emerged that could expose photographic plates and fluoresce screens even through opaque materials. He named these rays "X-rays" due to their unidentified nature and documented their ability to pass through soft tissues while being absorbed by denser structures like bones, laying the foundation for high-energy portions of the spectrum beyond ultraviolet. This serendipitous finding, reported in a preliminary communication to the Würzburg Physical-Medical Society, revolutionized imaging and spectral exploration.[30] Henri Becquerel accidentally discovered radioactivity in 1896 while studying phosphorescence in uranium salts, noticing that a uranium potassium sulfate crystal exposed a photographic plate even when shielded from light, indicating spontaneous emission of penetrating rays independent of excitation. Initially attributing this to a form of X-ray-like radiation from uranium, Becquerel's observations revealed continuous emission from the atomic nucleus through natural radioactive decay. His Comptes Rendus reports detailed the rays' ability to ionize air and discharge electroscopes. Subsequent studies identified components of this radiation, including gamma rays—highly energetic electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths shorter than X-rays—first observed by Paul Villard in 1900 from radium sources.[31] Philipp Lenard advanced understanding of the ultraviolet region in 1902 through meticulous photoelectric effect experiments, illuminating metal surfaces with UV light and measuring the ejected electrons' energies using retarding potentials. He found that electron emission occurred only above a threshold frequency specific to the metal, with kinetic energies increasing linearly with frequency rather than light intensity, challenging classical wave theory and suggesting a particle-like quantum interaction at UV wavelengths. These observations, conducted with improved vacuum tubes, provided early empirical hints at the quantized nature of electromagnetic energy in the near-UV spectrum.[32] In 1916, Robert Millikan quantitatively verified the quantum nature of light through photoelectric experiments, measuring stopping potentials for electrons ejected from clean metal surfaces under monochromatic UV and visible light to determine photon energies. Adapting techniques akin to his earlier oil-drop method for precision charge measurements, Millikan confirmed Einstein's equation , where is Planck's constant, is frequency, and is the work function, yielding erg-second—close to modern values—and establishing discrete photon energies across the spectrum. His Physical Review paper provided rigorous data supporting the corpuscular model for electromagnetic waves in the optical and UV ranges.[33]Spectrum Classification

Criteria for Regional Division

The electromagnetic spectrum is conventionally divided into discrete regions using arbitrary yet practical boundaries defined by wavelength or frequency thresholds, which facilitate scientific study, technological applications, and standardization. These divisions emerged from a combination of physical properties, such as photon energy, and practical considerations including detection methods and historical conventions. For instance, the spectrum spans from radio waves with wavelengths longer than 1 mm (frequencies below 300 GHz) to gamma rays with wavelengths shorter than 0.01 nm (frequencies above 30 EHz), with intermediate regions like microwaves (1 mm to 1 m), infrared (700 nm to 1 mm), visible light (400–700 nm), ultraviolet (10–400 nm), and X-rays (0.01–10 nm).[34] Such boundaries are not rigid but reflect how electromagnetic waves interact differently with matter at various scales, influencing their propagation and detection—radio waves are easily detected by antennas, while X-rays require specialized detectors like scintillation counters./University_Physics_II_-Thermodynamics_Electricity_and_Magnetism(OpenStax)/16%3A_Electromagnetic_Waves/16.06%3A_The_Electromagnetic_Spectrum) A key criterion for regional division is the distinction between non-ionizing and ionizing radiation, based on photon energy thresholds that determine biological and chemical effects. Non-ionizing radiation, with energies below approximately 10–12 eV (corresponding to frequencies under 3 × 10¹⁵ Hz), includes radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visible light, and most ultraviolet; it lacks sufficient energy to eject electrons from atoms, instead causing thermal or vibrational effects. Ionizing radiation, with energies above this threshold (ultraviolet below ~100 nm, X-rays, and gamma rays), can ionize atoms by removing electrons, leading to potential cellular damage. This boundary falls within the ultraviolet region, where the transition is gradual rather than sharp, as ionization potential varies by material.[35][34] Atmospheric absorption significantly influences these divisions by creating transmission "windows" where electromagnetic waves propagate with minimal attenuation, guiding practical classifications and applications. Earth's atmosphere is largely transparent in the radio (5 MHz to 300 GHz), near- and mid-infrared (roughly 0.7–5 μm and 8–14 μm), and visible (0.4–0.7 μm) bands due to low absorption by gases like water vapor, oxygen, and ozone, allowing ground-based observations and communications. In contrast, regions like far-infrared and portions of ultraviolet are heavily absorbed, necessitating space-based detection and reinforcing separate regional identities.[36] These windows have shaped subdivisions, such as the radio band's breakdown into extremely low frequency (ELF, 3–30 Hz) to very high frequency (VHF, 30–300 MHz) for navigation and broadcasting.[37] Classifications have evolved from an initial focus on the optical regime (visible light) in the 18th century to a comprehensive spectrum by the early 20th century, driven by sequential discoveries. Prior to 1800, only visible light was recognized; William Herschel's 1800 detection of infrared and Johann Ritter's 1801 ultraviolet findings expanded the boundaries, followed by James Clerk Maxwell's 1867 theoretical prediction and Heinrich Hertz's 1887 experimental confirmation of radio waves. Wilhelm Röntgen's 1895 discovery of X-rays and Paul Villard's 1900 observation of gamma rays completed the full spectrum, shifting classifications from wavelength-centric optical divisions to energy-based, multi-region frameworks that accommodate technological advancements like radar and spectroscopy. Overlaps exist across boundaries—for example, the microwave-infrared transition around 1 mm or ultraviolet-visible at 400 nm—due to continuous wave properties, with sub-divisions (e.g., near-, mid-, and far-infrared based on thermal effects) providing finer granularity for specialized uses.[24][34]Radio Waves

Radio waves represent the longest-wavelength portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, characterized by wavelengths greater than 1 millimeter, corresponding to frequencies below 300 GHz. This range encompasses the practical radio frequency bands allocated for various uses, starting from very low frequency (VLF) at 3–30 kHz, low frequency (LF) at 30–300 kHz, medium frequency (MF) at 300 kHz–3 MHz, high frequency (HF) at 3–30 MHz, very high frequency (VHF) at 30–300 MHz, and ultra high frequency (UHF) at 300 MHz–3 GHz, with higher sub-bands extending up to 300 GHz.[38] These waves are generated by accelerating electric charges, typically through oscillating currents in antennas, where the frequency of oscillation determines the emitted wave's frequency.[39] Propagation of radio waves occurs primarily through ground waves, which follow the Earth's curvature for medium-range communication, and sky waves, which reflect off the ionosphere to enable long-distance transmission beyond the horizon. The ionosphere, a layer of ionized plasma in the upper atmosphere, refracts and reflects radio waves—particularly those in the HF band—due to free electrons interacting with the wave's electric field, allowing signals to bounce multiple times for global reach. Atmospheric effects, such as absorption in the lower ionosphere during daytime, influence propagation reliability, but nighttime conditions often enhance sky-wave efficiency for international broadcasting.[40][41].pdf) With photon energies on the order of 10^{-12} to 10^{-3} eV—far below the 13.6 eV threshold for ionizing atomic hydrogen—radio waves are non-ionizing and pose no risk of chemical bond disruption in biological tissues. Quantum effects are negligible at these low frequencies and energies, permitting a classical electromagnetic treatment using Maxwell's equations without invoking photon discreteness. Key applications include amplitude modulation (AM) radio broadcasting in the MF band for wide-area audio transmission and frequency modulation (FM) radio along with television signals in the VHF band, which offer higher fidelity due to reduced interference from atmospheric noise.[34][42][43][44]Microwaves

Microwaves constitute a segment of the electromagnetic spectrum characterized by wavelengths ranging from 1 millimeter to 1 meter, corresponding to frequencies between 300 GHz and 300 MHz.[45] This range positions microwaves as the higher-frequency extension of radio waves, enabling distinct propagation and interaction properties suitable for specialized technologies. Unlike longer radio waves, microwaves exhibit reduced diffraction and greater susceptibility to atmospheric attenuation, yet they maintain the ability to penetrate obscurants such as clouds, dust, and light precipitation.[45] Microwaves are generated primarily through vacuum tube devices like klystrons and magnetrons, which convert electrical energy into high-power electromagnetic oscillations. Klystrons operate via velocity modulation of an electron beam across multiple resonant cavities, achieving amplification with efficiencies up to 50% and gains exceeding 60 dB, making them ideal for high-power applications in accelerators and communications.[46] Magnetrons, in contrast, produce microwaves by inducing cycloidal electron paths in a crossed electric and magnetic field within resonant cavities, yielding compact, high-efficiency sources (around 80%) commonly used in radar and domestic appliances.[47] For propagation, microwaves rely on waveguides—hollow metallic structures that confine and guide waves with minimal loss—and parabolic dish antennas, which provide high directivity and beam focusing for point-to-point transmission over distances.[45] Microwaves interact strongly with water molecules due to excitation of their rotational modes, leading to significant absorption in both liquid and vapor forms. In the atmosphere, water vapor produces a prominent absorption line at approximately 22.235 GHz, while oxygen contributes lines around 60 GHz, creating regions of high attenuation.[48] These effects define "microwave windows"—frequency bands with relatively low absorption, such as 8–12 GHz and segments near 22 GHz, that facilitate transmission for remote sensing and communication by minimizing signal loss through the troposphere.[49] Key applications of microwaves leverage these properties for practical technologies. In microwave ovens, a magnetron generates 2.45 GHz waves that cause dielectric heating by inducing molecular rotation in water, fat, and sugars within food, achieving efficient volumetric cooking with penetration depths of several centimeters.[47] Radar systems utilize pulsed microwaves in bands like X-band (8–12 GHz) for high-resolution detection of objects, weather patterns, and terrain, benefiting from the waves' ability to penetrate atmospheric haze.[45] Satellite communications employ microwave frequencies in C-band (4–8 GHz) and Ku-band (12–18 GHz) for reliable transcontinental data relay, capitalizing on the microwave windows to ensure signal integrity.[45] Wireless networking standards like Wi-Fi operate in the 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz bands, enabling short-range, high-data-rate connectivity in unlicensed spectrum allocations.[50] At shorter wavelengths approaching 1 mm (millimeter waves), microwaves transition to quasi-optical behavior, where wave propagation mimics light rays more closely, allowing treatment via geometric optics approximations for beam focusing, reflection, and diffraction in free space. This shift enables advanced quasi-optical systems, such as Gaussian beam propagation in high-frequency devices, bridging microwave engineering with optical techniques.Infrared Radiation

Infrared radiation occupies the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum adjacent to visible light, with wavelengths ranging from approximately 700 nanometers to 1 millimeter, corresponding to frequencies between 430 terahertz and 300 gigahertz.[25] This band is subdivided into near-infrared (0.7–5 μm), mid-infrared (5–30 μm), and far-infrared (30 μm–1 mm), though exact boundaries vary slightly across conventions; these divisions reflect differences in interaction with matter and technological applications.[51] Unlike shorter wavelengths, infrared is invisible to the human eye and primarily manifests as thermal radiation from objects at everyday temperatures. Infrared emission is a key feature of blackbody radiation, where the peak wavelength of emission follows Wien's displacement law: λ_max T = 2898 μm·K, meaning warmer objects peak at shorter infrared wavelengths while cooler ones, like room-temperature surfaces, emit predominantly in the mid- to far-infrared.[52] Detection typically relies on thermal sensors such as bolometers, which measure temperature changes from absorbed radiation via resistance variations, or thermocouples, which generate voltage from heat-induced junctions; these methods enable sensitive imaging across the infrared range without requiring cryogenic cooling for many applications.[53] Infrared radiation interacts with matter by exciting molecular vibrations and rotations, leading to characteristic absorption bands—for instance, carbon dioxide absorbs strongly at 4.3 μm due to asymmetric stretching modes, as detailed in high-resolution spectroscopic studies identifying over 90% of lines in this region.[54] As non-ionizing radiation, infrared primarily causes heating by transferring energy to molecular bonds rather than ejecting electrons, making it suitable for non-destructive sensing.[51] Practical applications include thermal imaging for detecting heat signatures in firefighting or search-and-rescue operations, remote controls using near-infrared light-emitting diodes at around 940 nm to transmit signals, and astronomy via telescopes like NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, which observed dust-enshrouded star-forming regions in the mid- to far-infrared from 2003 to 2020.[25] In Earth's energy balance, infrared plays a central role as the primary form of outgoing thermal radiation from the surface (peaking around 10 μm), with absorption by atmospheric gases like CO2 trapping about 5–6% of incoming solar energy and contributing to the natural greenhouse effect that raises global temperatures by roughly 30°C.[55]Visible Light

Visible light constitutes the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that is detectable by the human eye, spanning wavelengths from approximately 400 to 700 nanometers (nm), corresponding to frequencies between about 430 and 750 terahertz (THz).[56] This narrow band is subdivided into colors based on wavelength, progressing from violet at the shorter end (around 400 nm) to red at the longer end (around 700 nm), with intermediate hues including blue, green, yellow, and orange.[6] The human visual system perceives this spectrum through three types of cone photoreceptor cells in the retina, each tuned to peak sensitivities at distinct wavelengths: short-wavelength cones (S-cones) at about 420 nm (blue-violet), medium-wavelength cones (M-cones) at around 530 nm (green), and long-wavelength cones (L-cones) at approximately 560 nm (yellow-red).[57] These cones enable trichromatic color vision, where perceived colors arise from the combined responses of the cones, following additive color mixing models such as RGB (red, green, blue) used in digital displays.[58] Key optical properties of visible light include refraction and dispersion, which occur when light passes through media like glass prisms, causing shorter wavelengths (violet) to bend more than longer ones (red) due to wavelength-dependent refractive indices.[59] This phenomenon, first systematically demonstrated by Isaac Newton in the late 17th century, separates white light into its spectral components, producing rainbows in natural settings like atmospheric water droplets or artificial prisms.[60] Additionally, interference effects arise in thin films, such as soap bubbles or oil slicks on water, where the superposition of reflected light waves from the film's top and bottom surfaces creates colorful patterns depending on the film's thickness relative to the wavelength.[61] Primary sources of visible light include the Sun, whose blackbody radiation at about 5800 K peaks in the green-yellow region around 500 nm, delivering roughly 40-50% of its energy in the visible range to Earth's surface.[62] Artificial sources encompass incandescent lamps, fluorescent tubes, light-emitting diodes (LEDs) that emit specific colors via semiconductor bandgaps, and lasers producing coherent monochromatic beams, such as helium-neon lasers at 632.8 nm (red).[63] Applications leverage these properties in photography for capturing spectral scenes, display technologies like LCD and OLED screens employing RGB backlights for color reproduction, and fiber optic communications transmitting visible wavelengths over short distances in multimode fibers.[56] Biologically, visible light plays a central role in human vision, enabling object recognition and environmental navigation, while specific wavelengths influence physiological processes such as circadian rhythms, where blue light (around 450-480 nm) suppresses melatonin production via intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells, helping synchronize sleep-wake cycles to day-night patterns.[64] In plants, visible light drives photosynthesis, with chlorophyll pigments absorbing primarily blue (430-450 nm) and red (640-680 nm) wavelengths to convert light energy into chemical bonds, sustaining global ecosystems.[6]Ultraviolet Radiation

Ultraviolet radiation occupies the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum with wavelengths ranging from 10 to 400 nanometers, corresponding to frequencies between 750 terahertz and 30 petahertz.[26][3] This band is subdivided into three regions based on wavelength: UVA from 315 to 400 nm, UVB from 280 to 315 nm, and UVC from 100 to 280 nm, with each exhibiting distinct interactions with matter due to increasing photon energy.[26] Photon energies in this range span ~3–124 eV. While UV is generally classified as non-ionizing radiation that primarily affects molecular bonds rather than ejecting inner-shell electrons, shorter wavelengths (below ~124 nm) can cause ionization.[34] The Earth's ozone layer plays a critical role in filtering UV radiation, absorbing nearly all UVC and most UVB while allowing UVA to pass through more readily.[65] This absorption protects surface life from the most energetic UV components, as UVC is completely blocked by ozone and atmospheric oxygen.[65] Artificial sources of UV radiation include electric arcs, which emit broad-spectrum UV through plasma excitation, and mercury vapor lamps, which produce discrete UV lines, particularly at 254 nm in low-pressure configurations for targeted applications.[66][67] UV radiation drives key photochemical reactions by providing photons energetic enough to break molecular bonds, such as in the formation of stratospheric ozone where ultraviolet light photodissociates oxygen molecules:followed by recombination with another oxygen molecule to form ozone (, where M is a third body).[68] This process exemplifies UV's role in initiating chain reactions that alter atmospheric composition without requiring ionization.[69] Practical applications leverage UV's reactivity for sterilization, where UVC disrupts microbial DNA to inactivate pathogens in air, water, and surfaces.[70] In fluorescence, UVA excites electrons in materials to produce visible emission, enabling uses in detection and imaging.[71] Tanning beds employ UVA to stimulate melanin production for cosmetic skin darkening.[72] In astronomy, space-based observatories like NASA's Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) have mapped UV emissions from young stars across the universe, revealing star formation histories inaccessible from ground-based telescopes due to atmospheric absorption.[73] Exposure to UV radiation can cause acute health effects, including sunburn from erythema induced by UVB and DNA damage such as pyrimidine dimer formation that impairs cellular replication.[74] While non-ionizing, prolonged UVA and UVB exposure contributes to cumulative skin damage, emphasizing the need for protective measures against overexposure.[74]