Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Turkish folklore

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (April 2009) |

The tradition of folklore—folktales, jokes, legends, and the like—in the Turkish language is very rich, and is incorporated into everyday life and events.

Turkish folklore

[edit]Nasreddin Hoca

[edit]

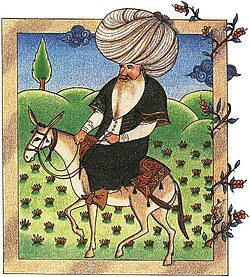

Perhaps the most popular figure in the tradition is Nasreddin, (known as Nasreddin Hoca, or "teacher Nasreddin", in Turkish), who is the central character of thousands of jokes.[1] He generally appears as a person who, though seeming somewhat stupid to those who must deal with him, actually proves to have a special wisdom all his own:

One day, Nasreddin's neighbor asked him, "Teacher, do you have any forty-year-old vinegar?"

—"Yes, I do," answered Nasreddin.—"Can I have some?" asked the neighbor. "I need some to make an ointment with."—"No, you can't have any," answered Nasreddin. "If I gave my forty-year-old vinegar to whoever wanted some, I wouldn't have had it for forty years, would I?"

Similar to the Nasreddin jokes, and arising from a similar religious milieu, are the Bektashi jokes, in which the members of the Bektashi religious order—represented through a character simply named Bektaşi—are depicted as having an unusual and unorthodox wisdom, one that often challenges the values of Islam and of society.

| Turkish literature |

|---|

| By category |

| Epic tradition |

| Folk tradition |

| Ottoman era |

| Republican era |

Karagöz and Hacivat

[edit]Another popular element of Turkish folklore is the shadow theater centered on the two characters of Karagöz and Hacivat, who both represent stock characters: Karagöz—who hails from a small village—is something of a country bumpkin, while Hacivat is a more sophisticated city-dweller. Popular legend has it that the two characters are actually based on two real persons who worked for Orhan I—the son of founder of the Ottoman dynasty—in the construction of a mosque at Bursa in the early 14th century CE. The two workers supposedly spent much of their time entertaining the other workers, and were so funny and popular that they interfered with work on the palace, and were subsequently put to death.

Yunus Emre

[edit]Yunus Emre was a Turkish folk poet and Sufi mystic who influenced Turkish culture.

Like the Oghuz Book of Dede Korkut, an older and anonymous Central Asian epic, the Turkish folklore that inspired Yunus Emre in his occasional use of tekerlemeler as a poetic device had been handed down orally to him and his contemporaries. This strictly oral tradition continued for a long while. As Islamic mystic literature thrived in Anatolia, Yunus Emre became one of its most distinguished poets. The poetry of Yunus Emre — despite being fairly simple on the surface — evidences his skill in describing quite abstruse mystical concepts in a clear way. He remains a popular figure in a number of countries, stretching from Azerbaijan to the Balkans, with seven different and widely dispersed localities disputing the privilege of having his tomb within their boundaries.

Köroglu

[edit]The Epic of Köroglu is a part of Turkish Folk Literature. The legend typically describes a hero who seeks to avenge a wrong. It was often put to music and played at sporting events as an inspiration to the competing athletes. Köroglu is the main hero of epic that tells about the life and heroic deeds of Köroglu as a hero of the people who struggled against unjust rulers. The epic combines the occasional romance with Robin Hood-like chivalry.

Folklore from the Black Sea Region

[edit]Vine-breaking

[edit]In Çarşıbaşı town, near Trabzon, there is a way of testing whether a marriage is propitious: when the new bride enters the house, she is asked to break a vine into three pieces, which are then planted in the ground. If they sprout, this means the marriage will be successful.

Cutting the shoelace

[edit]In the Eastern Black Sea Region (Giresun, Trabzon, Rize, Artvin), it is believed that there is an invisible lace between the feet of those children who have trouble walking when they're young. A lace is tied (usually of cotton) between the feet of the child and the lace is cut by the elder child of family. It is believed that once the invisible lace has been cut, the child will walk.

Passing beneath a bramble

[edit]In Turkish folklore, (Trabzon region, Akçaabat town), childless women, cows that don't get pregnant, and children wetting their beds are supposedly cured by passing under a blackberry bush known as "Avat" (west Trabzon). “Avat is believed to be a charm herb of paradise.”

Shown to the Moon

[edit]In Trabzon and Rize region folklore (Pontic coast of Anatolia). Desperate patients with incurable diseases are said to have been shown to the Moon on a wooden shovel “If that continues I will put you on a shovel and show you to the moon”(İkizdere town. In Çarşıbaşı district of Trabzon province, weak and scrawny babies have been shown to the Moon on a shovel and said: “moon! moon! Take him!, or cure him”. In this tradition, which is a sequel to the paganist beliefs before the monotheist religions, the Moon cures the patient or takes his/her life. Moon worship is very common among the Caucasian Abkhaz, Svans and Mingrelians ABS 18.

Tying someone

[edit]In Black Sea coast of Turkey's folklore (Trabzon, Rize, Giresun, Ordu, Artvin, Samsun)

1. v. To ensure a bridegroom is bewitched and impotent so as to be unable to have sexual intercourse with bride. There are several ways of being tied: A person who wants to impede this marriage, blows into a knot, knots it and puts it on the bride or uses other sorceries. However, it is also deemed a way of being tied if the bride nails, knots or locks a door with a key before the marriage. “While going to the house of the bridegroom, way is always changed and the unlooked-for ways are followed to be saved from tie sorceries that could have been buried in the way” 2. n. To tie the animals such as wolves and bears that harm the flock and named monster, and swine that damages the crop. Generally, an amulet is prepared by a hodja and buried in the places where the flock grazes or in the corner of sown field. 3. n. To increase the amount and quality of meadow before the hay-making time, water is brought to the meadows in the plateaus in thin directions from rivers by the arcs. This process is called as to connect water.

Tree worship

[edit]According to the folklore of Trabzon, the swinging of tree branches and fluttering of their leaves symbolise worship. It is believed that oak trees do not worship God because their leaves do not move in the wind as much as those of other trees.

Şakir Şevket says that Akçaabat society believed in an idol and worshipped a tree called platana, and that is how the city was given this name. Although the platana (Platanus orientalis in Latin) was a plane tree he had confused this tree with the poplar.

The words of Lermioglu “today peasants love trees as their children. There were several events which people kill someone for a tree” and a story from 19th century show us that this love comes from very old days. A hunter from Mersin village cut a tree called kragen which was idol of Akcaabat society (since 1940). Then the peasants called the police and said that the hunter cut the Evliya Turkish and Arabic Evliya “Saint”). At first the police understood that the hunter killed a man called Evliya (Saint) but later they saw that the “saint” was a tree so they let the hunter go.

It is possible to see same things in Hemsheen region of Rize “the branches are praying three days before and during bairam, so we do not cut live branches during bairam, the branches are praying”.

End of winter Cemre

[edit]Cemre are three fireballs that come from the heavens to warm earth at the end of each winter. Each cemre warms one aspect of the nature. The first cemre falls to air between February 19–20. The second cemre falls to water between February 26–27. The third cemre falls to ground between 5–6 March.

Important figures in Black Sea folklore

[edit]Beings and creatures in Turkish folklore

[edit]- Al Basti

- Bardi - a female jackal which can change shape and presages death by wailing[citation needed]

- Bird of Sorrow [1]

- Dew (also called div) [2]

- Dragons

- Dunganga[citation needed]

- Giant 'Arab' or 'Dervish' [3]

- Imp [4]

- Kamer-taj, the Moon-horse [5]

- Karakoncolos

- Karakura - a male night demon[citation needed]

- Keloglan [6]

- Laughing Apple and Weeping Apple [7]

- Peris [8]

- Seven-headed Dragon [9]

- Storm Fiend [10]

- Tavara[citation needed]

- Shahmaran, the legendary Snake King who was killed in an ambush in the baths.

- Taram Baba, the night demon or nightmare which is believed to kidnap children, in some Balkanic Turks' tradition.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Javadi, Hasan. "MOLLA NASREDDIN i. THE PERSON". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- Özhan Öztürk (2005). Karadeniz: Ansiklopedik Sözlük. 2 Cilt. Heyamola Yayıncılık. İstanbul. ISBN 975-6121-00-9.

- Kunos, Ignaz (1913). Forty-four Turkish fairy tales. London: G. Harrap.

Further reading

[edit]- On folktales

- Preston, W. D. (1945). "A Preliminary Bibliography of Turkish Folklore". The Journal of American Folklore. 58 (229): 245–51. doi:10.2307/536613. JSTOR 536613. Accessed 23 Jan. 2023.

- Eberhard, W.; Boratav, Pertev N. (1945). "The Development of Folklore in Turkey". The Journal of American Folklore. 58 (229): 252–54. doi:10.2307/536614. JSTOR 536614. Accessed 23 Jan. 2023.

- Eberhard, Wolfram; Boratav, Pertev Nailî (1953). Typen türkischer Volksmärchen (in German). Wiesbaden: Steiner. doi:10.25673/36433.

- Anderson, Walter (1953). "Der türkische Märchenschatz". Hessische Blätter für Volkskunde (in German). XLIV: 111–132.

- Birkalan-Gedik, Hande. "The Types of Turkish Folktales". In: Angelopoulos, A. & al., eds. Cahiers de littérature orale 57-58. Paris: Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales / Centre de Recherche sur L'oralité, 2005. pp. 317-329. ISSN 0396-891X.

- Sakaoğlu, Saim (2010). "Türk masal tipleri kataloğu taslağı üzerine" [On the Draft Catalog of Turkish Folktale Types]. Milli Folklor. 22 (86): 43–49.

- Folktale collections

- Kúnos, Ignaz (1905). Türkische Volksmärchen aus Stambul. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Theodor Menzel. Billur Köschk: 14 türkische Märchen, zum ersten mal nach den beiden Stambuler Drucken der Märchensammlung ins Deutsche übersetzt. Hannover: Lafaire, 1923 [erschienen] 1924

- Jacob, Georg; Menzel, Theodor. Beiträge zur Märchenkunde des Morgenlandes. III. Band: Türkische Märchen II. Hannover: ORIENT-BUCHHANDLUNG HEINZ LAFAIRE, 1924.

External links

[edit]Turkish folklore

View on GrokipediaHistorical and Cultural Foundations

Origins in Turkic and Anatolian Traditions

Turkish folklore traces its deepest roots to the shamanistic traditions of Central Asian Turkic peoples, such as the Göktürks from the 6th century CE, carried forward by waves of Oghuz nomads who migrated to Anatolia beginning in the 11th century. These nomadic peoples practiced a form of Tengrism, centered on the worship of Tengri, the eternal blue sky god who embodied cosmic order and was revered as the supreme deity by ruling classes across steppe empires from the 3rd century BCE onward.[9] Shamanism, integral to this belief system, involved mediators known as kams who invoked ancestral spirits through rituals, divination, and healing to maintain harmony between the human world and supernatural forces.[10] A prominent totem in these traditions was the gray wolf, or Bozkurt, symbolizing the ancestral origin of the Turks; ancient myths depict the tribe's forefathers descending from the sky alongside a protective sky wolf, which guided survivors from catastrophe and became a emblem of resilience and national identity.[11] Upon settling in Anatolia from the 11th century onward, these Turkic elements intertwined with pre-existing indigenous folklore from earlier civilizations, including Hittite, Phrygian, and Byzantine traditions that persisted into the pre-Ottoman era. The Hittites, dominant from the 17th to 12th centuries BCE, practiced religion involving mother goddesses and fertility rituals that included music and processional elements to ensure prosperity. Phrygian influences, evident from the 8th century BCE, centered on Cybele as the Great Mother Goddess, whose worship involved ecstatic ceremonies and iconography emphasizing her role as nurturer of life and protector of the land, with roots tracing back to Anatolian prehistoric cults.[12] Byzantine folklore, blending Greco-Roman and local Anatolian elements through the 11th century, incorporated these influences into rural customs and communal festivals celebrating seasonal renewal and social bonds. A cornerstone of these blended traditions is the Book of Dede Korkut, a collection of twelve epic narratives from the Oghuz Turks, transmitted orally from the 9th to 15th centuries CE before being committed to manuscripts. These tales, framed around the wisdom of the bard Dede Korkut, recount heroic deeds amid tribal migrations and conflicts, embodying Oghuz values of honor, bravery, and kinship.[13] A representative story features the hero Basat, raised by wild animals, who defeats the monstrous one-eyed giant Tepegöz— a demon devouring Oghuz tribespeople—through cunning and a enchanted sword, symbolizing the triumph of human ingenuity over chaos.[13] Shamanistic practices from these origins emphasized harmony with nature spirits, including veneration of sacred trees as cosmic axes connecting the realms of gods, humans, and underworld entities. In pre-Islamic Turkic culture, trees like birch and oak served as sites for prayers and offerings, where fabric ribbons were tied to branches to convey wishes to Tengri or ancestral deities, reflecting beliefs in trees as living embodiments of fertility and the universe's structure.[14] Animal sacrifices, such as cattle rituals, were performed to appease spirits and ensure communal well-being, with blood offerings sprinkled on natural features to invoke protection and balance in the nomadic worldview.[10] These elements laid the foundational animistic and heroic framework for Turkish folklore, later synthesizing with incoming influences.Islamic and Ottoman Influences

The arrival of Islam in Anatolia during the 11th century, facilitated by the Seljuk Turks' conquests, marked a pivotal transformation in local belief systems, blending Islamic tenets with pre-existing shamanistic practices to form syncretic elements in Turkish folklore.[15] This fusion is exemplified by the figure of Hızır, an eternal saint in Islamic tradition who merges with pre-Islamic motifs of a verdant, life-giving green man associated with renewal and nature spirits.[16] In folk narratives, Hızır embodies immortality and aid to the distressed, often appearing as a wandering helper whose green attire symbolizes fertility and shamanistic reverence for natural forces, thus bridging divine intervention with indigenous animistic views.[17] During the Ottoman Empire's span from the 14th to the 20th centuries, imperial patronage elevated oral storytelling traditions, particularly through the support of meddah performers who recounted tales in coffeehouses, markets, and even the sultan's court.[18] These storytellers developed a repertoire of moralistic narratives that emphasized themes of justice, piety, and ethical conduct, drawing from Islamic ethics to reinforce social harmony and religious devotion within diverse audiences.[18] Such tales often portrayed virtuous protagonists overcoming injustice through faith, serving as didactic tools that integrated Ottoman societal values into everyday folklore.[19] Sufi orders, notably the Bektashi, profoundly shaped Alevi folklore by infusing it with mystical themes of divine love and subtle rebellion against oppressive authority, reflecting the order's heterodox interpretations of Islam.[20] Emerging in 13th-century Anatolia, Bektashi teachings emphasized personal spiritual union with the divine, influencing Alevi oral traditions, hymns, and rituals that celebrate ecstatic love for God while critiquing rigid hierarchies.[21] This influence fostered folklore motifs of marginalized heroes pursuing inner enlightenment amid persecution, blending Sufi esotericism with communal resistance narratives.[20] Islamic lore further enriched Turkish beliefs through the incorporation of jinn, known as cin, supernatural beings capable of interacting with humans in both benevolent and malevolent ways.[22] Adapted into local customs, cin feature prominently in tales of possession and mischief, with variants like the ifrit depicted as fiery, powerful entities that seize individuals, granting unnatural strength but often leading to torment or moral downfall.[23] These stories, rooted in Quranic references yet localized through Ottoman-era anecdotes, warn against spiritual vulnerability while highlighting protective rituals like recitations to ward off such intrusions.[24]Iconic Narrative Figures

Nasreddin Hoca

Nasreddin Hoca, also known as Nasreddin Hodja, was a 13th-century Sufi dervish and satirical figure believed to have lived in Anatolia during the Seljuq era. Born around 1208 in the village of Hortu near Sivrihisar in present-day Eskişehir Province, he later settled in Akşehir in the Konya region, where he served as an imam and scholar until his death in 1284.[25][26] As a member of the Sufi tradition, his life intertwined spiritual teachings with everyday humor, drawing from Turkic and Islamic cultural elements in the region.[27] His legacy endures through hundreds of anecdotes attributed to him, with collections exceeding 350 stories in some compilations, such as those documented in Turkish folklore archives.[28] These tales, often compiled in works like Nasreddin Hoca Latifeleri, portray him as a wise fool whose absurd logic exposes human follies.[29] Key examples include the cauldron anecdote, where Hoca borrows a neighbor's pot, returns it with a smaller one inside claiming it "gave birth," and later returns an empty pot after a second borrowing, declaring the original "died"—a clever trick satirizing gullibility and perpetual debt.[30] Another famous story involves the lost key, in which Hoca searches for it under a streetlamp despite losing it in the dark, explaining, "This is where the light is," to highlight the folly of looking only where it's convenient rather than where truth lies.[31] A third tale features Hoca weighing a load of butter by placing it on one side of scales and himself on the other, then subtracting his weight, symbolizing self-aware ingenuity in outwitting authority figures like a demanding official.[32] The cultural impact of Nasreddin Hoca extends across Turkish folklore and beyond, recognized by UNESCO in 2022 as an element of intangible cultural heritage through a multinational nomination involving Türkiye, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan.[33] This inscription honors the tradition of telling his anecdotes during social gatherings and festivals, which foster community bonds and moral reflection. In Akşehir, an annual International Nasreddin Hoca Festival held from July 5 to 10 features storytelling, performances, and reenactments, attracting visitors to his tomb and reinforcing local identity.[34] His stories have influenced folklore in the Balkans, Middle East, and Central Asia, where variants appear in Persian, Arabic, and other languages, adapting his character to local contexts while preserving themes of wit against oppression.[35] At the core of Nasreddin Hoca's narratives are themes of absurd logic that illuminate social hypocrisies, such as greed, pretension, and blind adherence to rules, often delivered through humble, everyday scenarios.[36] These tales promote humility and practical philosophy, using satire to critique authority without direct confrontation, a approach rooted in Sufi teachings of inner wisdom over outward displays.[26] By embodying the archetype of the wise fool, Hoca's anecdotes encourage listeners to question assumptions and find truth in simplicity, making them timeless tools for ethical guidance in Turkish and broader Islamic cultural spheres.[33]Köroğlu

Köroğlu is a legendary epic hero in Turkish folklore, originating from a 16th-century tale centered on Yusuf, a stable master blinded by the tyrannical Bolu Bey as punishment for delivering an unsatisfactory horse.[37] This act of injustice transforms Yusuf's son, Ruşen Ali (later known as Köroğlu, meaning "son of the blind one"), into a rebel leader who avenges his father by assembling a band of outlaws to challenge oppressive rulers.[38] The core narrative revolves around Köroğlu's daring theft of the miraculous grey horse Kırat, a supernatural steed born from a mare and capable of extraordinary feats like leaping great distances and swimming rivers, which becomes his indispensable companion in battles fought with both sword and improvised poetry.[39] These exploits include establishing a stronghold at Çamlıbel and raiding caravans to aid the downtrodden, with the epic featuring romantic subplots such as Köroğlu's abduction of the beloved Nigar.[37] Variants of the story extend to Azerbaijan and Iran, where the hero's rebellion often incorporates Shi'a elements or shifts focus to conflicts with Safavid authorities, reflecting cross-cultural adaptations while retaining the theme of justice against feudal lords.[38] The epic is performed as a destan by wandering âşık bards, who recite it in a mix of prose and verse during social gatherings such as weddings and traditional oil wrestling matches known as yağlı güreş.[39] These oral renditions, accompanied by string instruments like the saz, allow for improvisation and regional flavoring, preserving the tale's vitality in Anatolian communities.[37] Over 500 versions have been recorded across Turkic-speaking regions, showcasing the epic's evolution through bardic transmission since its emergence amid the Celali rebellions.[40] Köroğlu symbolizes folk resistance to Ottoman oppression, embodying the archetype of the noble bandit who defends the weak against corrupt authority, much like a Turkish Robin Hood.[38] Central themes include unwavering loyalty to kin and comrades, unyielding bravery in the face of tyranny, and the supernatural horse Kırat as an emblem of untamed freedom and divine favor for the righteous cause.[39]Yunus Emre

Yunus Emre was a 13th-century Sufi poet born around 1240 in the village of Sarıköy, located between Mihalıççık and Sivrihisar in present-day Eskişehir province, Anatolia.[41] Originating from humble peasant roots, he was illiterate yet received divine inspiration that enabled him to compose profound mystical verses.[42] As a wandering dervish, Emre traveled extensively across Anatolia, serving in Sufi lodges and spreading teachings of spiritual devotion during a period of Mongol invasions and social upheaval.[43] He is believed to have died around 1320, at approximately 80 years of age.[44] Emre's primary collection, the Divan-ı Yunus Emre, comprises over 300 poems written in simple, accessible Old Anatolian Turkish, making mystical concepts available to the common people rather than elites versed in Persian or Arabic.[45] These works include ilahiler (spiritual hymns) that emphasize moral lessons on humility, compassion, and the unity of creation with the divine, often structured in rhythmic, repetitive forms reminiscent of folk oral traditions.[46] Through such poetry, Emre conveyed Sufi principles of inner purification and love for all beings, drawing from his experiences in dervish communities. One of his most renowned verses captures the essence of universal love: "Yaradılanı severim Yaradan'dan ötürü" ("I love the created for the sake of the Creator"), underscoring themes of humility and interconnectedness that permeate his oeuvre. This line exemplifies how Emre's words promote tolerance and divine empathy, influencing listeners to transcend ego and embrace creation as a reflection of the divine. Emre's legacy endures as a key figure in the development of the Turkish language, credited with enriching its vernacular expression through everyday mysticism that bridged folk and religious spheres.[47] Shrines dedicated to him exist in Karaman, featuring a 14th-century mosque and tomb complex from the Karamanid period, and in Sarıköy, marking his birthplace as a site of pilgrimage.[48] His verses continue to shape Alevi semah rituals, where they are recited and sung during communal ceremonies to invoke spiritual harmony, and inspire modern Turkish folk music, with numerous compositions adapting his hymns for contemporary performances.[49][50]Performing Arts and Oral Traditions

Karagöz and Hacivat Shadow Theater

Karagöz and Hacivat shadow theater, a cornerstone of Ottoman performing arts, originated from a legendary tale set in 14th-century Bursa during the reign of Sultan Orhan Gazi. According to tradition, Karagöz and Hacivat were construction workers on the Ulu Cami mosque project whose witty banter distracted fellow laborers, delaying the work; in response, the sultan ordered their execution. A dervish named Şeyh Küşteri, moved by their humor, later crafted shadow puppets of the pair to reenact their dialogues, thus birthing the art form as a means of consolation and entertainment.[51][52] The central characters embody contrasting social archetypes central to the theater's appeal. Hacivat represents the educated elite—pompous, articulate, and scheming—often speaking in refined Ottoman Turkish laced with pretentious poetry and proverbs. In opposition, Karagöz is the illiterate everyman, clever yet naive, hailing from rural Anatolia; his blunt, folksy responses in a regional dialect expose hypocrisies and generate comedy through misunderstandings and wordplay. These figures, along with a ensemble of stock characters like the coquettish Zenne or the drunken Tuzsuz Deli Bekir, populate improvised scenarios that highlight human quirks.[51][52] Performances feature translucent leather puppets, known as tasvir, crafted from camel or ox hide, meticulously cut, painted, and mounted on thin rods for manipulation behind a white cotton screen called cam. A single puppeteer, the hayali, voices all roles while an assistant handles music with instruments like the tef (tambourine) and kaşık (spoons) and provides sound effects; light from oil lamps or modern bulbs projects exaggerated shadows onto the screen, enhancing the satirical flair.[52][53] The art reached its zenith in the 17th and 18th centuries, with master puppeteers maintaining repertoires of at least 28 traditional plays, performed in coffeehouses during Ramadan or festivals, employing Central Anatolian dialects for humorous effect.[52][53] Thematically, Karagöz and Hacivat satirize class divisions, bureaucratic absurdities, and universal follies, using the duo's interactions to critique societal norms without direct confrontation. In episodes like the archetypal "Hacivat's Visit," Hacivat's pompous arrival at Karagöz's humble abode leads to chaotic misunderstandings—such as Karagöz misinterpreting formal invitations as threats—mocking pretension and celebrating the unpretentious wisdom of the common folk. This blend of slapstick, puns, and social commentary fostered communal laughter and reflection in Ottoman urban life.[51][54] Today, the tradition endures as a UNESCO-listed Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity since 2009, safeguarding its role in preserving Turkish cultural identity. The annual International Bursa Karagöz Festival, held since 1993, revives performances in historic settings, while adaptations extend to contemporary media, including the 2006 film Hacivat Karagöz Neden Öldürüldü? directed by Ezel Akay, which dramatizes the origin legend, and occasional television sketches that reinterpret the characters for modern audiences.[52][51][55]Aşık Bards and Epic Recitation

The âşık tradition, a cornerstone of Turkish oral folklore, consists of itinerant poet-singers known as âşıks who perform improvised verses accompanied by the saz, a long-necked lute, preserving cultural narratives through music and storytelling.[56] Originating from the 11th-century migration of Oghuz Turkmen tribes into Anatolia during the Seljuk era, the practice evolved from ancient Turkic shamanistic and bardic roles, such as the ozan figures in the Dede Korkut stories, and flourished under Ottoman influences in coffeehouses and villages.[57] Training typically occurs through a prolonged apprenticeship in Sufi lodges (tekkes), particularly those affiliated with Alevi-Bektashi orders, where aspiring âşıks learn saz playing, poetic improvisation, and ethical principles, often inspired by a visionary dream signaling their calling.[56] Renowned âşıks include the 17th-century Karacaoğlan, celebrated for his earthy love lyrics, and Aşık Veysel (1894–1973), a blind Sivas-born poet who blended traditional forms with modern themes of humanism and rural life.[58][57] The âşıks' repertoire encompasses a rich array of syllabic verse forms, emphasizing improvisation and oral composition without written notation. Destans are epic narratives, such as variants of the Köroğlu tales recounting heroic rebellions against tyranny, while semais offer lyrical reflections on nature and romance, and koçaklamas deliver boastful challenges or satirical jabs.[56][57] Common themes include romantic longing, moral dilemmas, warfare, and social critique, often concluding with a quatrain bearing the poet's pseudonym (mahlas) for personal signature.[56] Some âşıks employ linguistic constraints, like avoiding certain consonants (e.g., B, P, V, M, F) by using a needle as a mnemonic aid during performance.[56] Socially, âşıks serve as communal educators and entertainers, performing at village gatherings, weddings, and festivals to transmit folklore, foster dialogue, and offer moral guidance through satire and wisdom.[56] Their improvisational contests, known as âşık atışması, pit rivals in verbal duels of wit and rhyme, resolving disputes or showcasing prowess in front of audiences.[56] This oral tradition reinforces social cohesion across classes, from rural nomads to Ottoman elites, by embedding ethical values and historical memory in accessible song.[57] From its nomadic roots in Central Asian steppes, the âşık tradition adapted to sedentary Anatolian life, gaining prominence in the 17th century as documented by traveler Evliya Çelebi, and later transitioned to modern media through radio broadcasts in the mid-20th century, which popularized figures like Aşık Veysel nationwide.[57][5] In 2009, UNESCO inscribed the âşıklık tradition on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, recognizing its role in enriching Turkish literary and communal heritage, with ongoing festivals sustaining performers like those honoring Karacaoğlan.[56]Customs, Rituals, and Beliefs

Festivals and Seasonal Rites

Turkish folklore is rich with festivals and seasonal rites that mark the agricultural cycles, communal transitions, and natural renewals, often blending pre-Islamic Turkic shamanistic elements with later Islamic influences. These events foster social cohesion and invoke blessings for fertility, prosperity, and protection against seasonal hardships. Among the most prominent are spring heralds like Hıdırellez and the Cemre periods, alongside ritualistic celebrations tied to life milestones such as weddings and displays of physical prowess in oil wrestling. Hıdırellez, observed annually from the evening of May 5 to May 6, celebrates the meeting of Hızır, the protector of vegetation and earthly abundance, and İlyas, the guardian of skies and waters, symbolizing the union of earth and heaven that awakens nature from winter dormancy.[59] This festival, deeply rooted in Turkic traditions and recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage, involves rituals to ensure family wellbeing, crop fertility, and livestock health. Communities gather for picnics in green spaces, where participants write wishes on paper and tie them to rosehip branches or other trees, believing the bark absorbs their desires for the coming year.[59] Another key custom is lighting bonfires and jumping over them three times to purify the body and spirit, promoting health and warding off misfortune while invoking renewal.[59] These practices highlight the festival's role in transitioning from scarcity to abundance, with families preparing special foods like sweets and sharing communal meals under the stars. The Cemre, or "hot coals," represent three sequential infusions of warmth into the world at winter's end, occurring roughly in late February and early March: the first to the air around February 19-20, the second to water on February 26-27, and the third to earth on March 5-6.[60] In Turkish folklore, these invisible embers, sent from the heavens, signal the gradual defeat of cold and the onset of spring's regenerative forces, influencing folk calendars and meteorological beliefs across Anatolia.[60] Particularly in the Black Sea region, such as Rize and Trabzon, communities mark each Cemre with bonfires to mimic and hasten the warming process, accompanied by prayers for bountiful harvests and family safety.[60] These rites reflect ancient animistic views of nature's vitality, where fire symbolizes life's rekindling, and participants often share proverbs or recite verses to honor the seasonal shift. The Kırkpınar oil wrestling tournament in Edirne, held annually since the 1360s, stands as one of the world's oldest continuous sporting events and a cornerstone of Turkish seasonal rites, embodying communal strength and Ottoman-era valor.[61] Wrestlers, known as pehlivans, coat themselves in olive oil and compete in bouts that can last hours, striving for the golden belt awarded to the champion, with the event drawing thousands for its blend of athleticism and ritual.[61] Rooted in nomadic Turkic warrior traditions, the festival invokes heroic figures from folklore, such as Köroğlu, through recitations by the cazgir (announcer), who calls competitors with poetic invocations emphasizing honor and endurance.[62] Accompanied by davul drums and zurna pipes, and beginning with prayers at the Selimiye Mosque, Kırkpınar symbolizes masculine prowess and communal unity, preserving Ottoman heritage while adapting to modern audiences.[61] Kına gecesi, or henna night, serves as a vital pre-wedding rite typically held the evening before the ceremony, focusing on the bride's symbolic passage from her family to her new life.[63] Exclusively or predominantly a women's gathering in Sunni traditions, it features the application of henna to the bride's palms by a groom's female relative, often using a gold coin to gently open her hands, signifying fertility, good fortune, and the binding of marital ties.[63] The event is enlivened by folk songs like "Yüksek Yüksek Tepelere" and regional kına türküleri, sung amid tears and laughter to evoke the bride's bittersweet departure, while dances such as horon or zeybek fill the space with rhythmic celebration.[63] Participants don traditional attire like red bindallı dresses, and the ritual underscores gendered cultural norms, blending joy with solemnity to bless the union's prosperity; occasionally, protective amulets are incorporated to safeguard the couple.[63]Superstitions and Protective Practices

In Turkish folklore, the belief in the evil eye, known as nazar, is a pervasive superstition positing that an envious or admiring gaze can inflict harm, misfortune, or physical ailments such as headaches, fatigue, or sudden illness on the targeted individual. This concept is deeply rooted in cultural practices aimed at averting such negative energy, with protections including the widespread use of nazar boncuğu, a blue glass bead crafted to resemble an eye, believed to absorb and reflect the malevolent gaze back to its source.[64] The craftsmanship, practices, and beliefs surrounding the nazar boncuğu were inscribed on UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2020. Additional safeguards involve hanging garlic or scattering salt in homes and on persons, as these items are thought to neutralize the curse's potency through their purifying properties.[65] Symptoms of nazar affliction are often addressed by reciting prayers or performing rituals like burning incense, underscoring the everyday vigilance against this intangible threat.[66] Protective rituals surrounding brides in rural Turkish traditions emphasize warding off misfortune during the vulnerable transition to married life. A common practice involves the bride's father tying a red ribbon around her waist before the ceremony, symbolizing fertility, prosperity, and a barrier against the evil eye to ensure a harmonious union.[67] In some regions, the bride participates in the testi kırma ritual, smashing a clay pot filled with water or coins at the threshold of the groom's home, which is believed to shatter potential bad luck and release blessings for marital strength and longevity. These customs, often performed amid chants and communal gatherings, reflect a cultural emphasis on symbolic acts to bind positive forces and repel harm, particularly in agrarian communities where such rites reinforce social bonds and personal security.[68] In Turkic traditions preserved in Turkish folklore, wolf parts—such as skins, bones, teeth, claws, and fat—have been fashioned into talismans hung on stables or worn by herders, invoking the animal's strength to deter attacks from predators like wolves and bears and to bind malevolent influences that could sicken or steal herds. Similar protections extend to tying knotted cords or placing iron objects near enclosures, rituals intended to trap evil spirits and prevent calamity, drawing from ancient Turkic reverence for wolves as totemic guardians despite their dual role as peril. These practices highlight the integration of animistic beliefs in daily agrarian life, where harmony with nature's dangers is maintained through prophylactic folklore. Household customs in Turkish culture prioritize protection for vulnerable members, especially newborns, who are deemed particularly susceptible to nazar. Blue bead amulets are routinely placed above cribs or attached to clothing to shield infants from envious glances that could cause colic or unexplained crying.[69] To avert jinxes after expressing optimism or praising good fortune, individuals knock on wood—often an unpainted door or tree—to humbly seek nature's favor and prevent reversal by fate.[70] Complementing this, spitting three times serves as an immediate exorcism of budding misfortune, a gesture rooted in beliefs that saliva repels demons or jinn, which folklore sometimes links to possessions manifesting as erratic behavior.[71] These rituals, performed instinctively across urban and rural settings, embody a resilient cultural framework for navigating uncertainty.Supernatural Beings and Creatures

Demons and Malevolent Spirits

In Turkish folklore, demons and malevolent spirits represent a blend of pre-Islamic Turkic shamanistic beliefs and Islamic influences, manifesting as harmful entities that prey on human vulnerabilities such as fear, illness, and death. These beings are often localized adaptations of broader supernatural motifs, emphasizing protection through rituals and everyday objects. Central to this lore are spirits like the Alkarısı, Karakoncolos, Cin, and Ubır (also known as Hortdan), each associated with specific perils and countermeasures rooted in Anatolian traditions.[72][73] The Alkarısı is a notorious childbirth demon prevalent in Central Anatolian folklore, depicted as a malevolent female spirit that targets pregnant women, new mothers, and infants during vulnerable postpartum periods. Resembling an ugly, fat woman with long, tangled hair and sharp nails, it induces terror, physical ailments, or even death by allegedly consuming organs like the lungs or liver, often linked to explanations for postpartum complications such as fever or depression. To ward it off, communities employ iron objects like pins and needles on clothing, red ribbons or wool threads around beds, constant lighting, and placements of bread or the Quran near the cradle; regional variants include names like Hıbılık in Malatya or Kapoz in Bingöl, reflecting localized fears in eastern and central Turkey.[72][74] Karakoncolos serves as a winter bogeyman in Turkish lore, particularly from Central Anatolia and the Black Sea region, emerging during the harshest cold months from December to February, known as Zemheri or the "dreadful cold." This hairy, animal-like entity haunts dark nights, causing hallucinations and intense fear, especially among children, by lurking at crossroads or corners to disturb passersby with eerie whispers or sudden appearances. It is repelled by sources of light, loud noises, or staying indoors, embodying seasonal anxieties tied to isolation and the unknown in rural Anatolian winters.[75] Cin, the Turkish adaptation of Islamic jinn, are shape-shifting spirits that haunt ruins, forests, and abandoned places, drawing from both Quranic traditions and indigenous beliefs to embody mischief or outright malevolence. In Turkish variants, these invisible or polymorphous entities possess individuals, leading to unexplained illnesses, sleeplessness, or hallucinatory encounters that blur reality, often triggered after sunset or through curses. Possession is countered by exorcisms involving the recitation of Quranic verses or rituals performed by specialists like cindar (jinn masters), who negotiate with or expel the spirits using sacred invocations. Cin musallat hikayeleri, or jinn possession stories, form a significant part of Turkish folklore, illustrating the manifestations, triggers, and countermeasures associated with these entities. Possession often results in physical ailments such as hunchback, paralysis, lameness, facial distortions, inability to urinate or move limbs, reduced hearing, strabismus, malaria-like symptoms, and bedridden illness, as well as mental distress including fainting, delirium, loss of mental balance, muteness from fear, self-talking, shouting, laughing, and even death. These encounters commonly occur in desolate locations like cemeteries, mills, wells, caves, hamams, stables, forests, abandoned houses, toilets, and lake shores, triggered by actions such as harming jinn (e.g., shooting or crushing them), polluting their spaces (e.g., urinating or pouring hot water), or venturing alone at night. Protective rituals include reciting prayers like Ayet-el Kürsi, Fatiha, and Yasin-i Şerif, invoking besmele before actions, and using iron objects such as needles, knives, or seals to ward off or trap jinn; for instance, placing the Quran or iron items near postpartum women and infants provides safeguarding. Examples from folklore include a man who urinates in a desolate place, faints, and awakens with a hunchback as punishment, or a family rewarded by jinn with multiplied food for respecting their space, highlighting both punitive and benevolent interactions. Culturally, these stories enforce social norms by deterring uncleanliness, pollution of sacred spaces, nighttime wandering, and prideful behavior, while promoting hygiene, prayer, community vigilance, and protection of vulnerable groups to maintain moral and social order.[78] The Ubır, or Hortdan, functions as a vampiric undead in Turkic and Anatolian folklore, arising from improper burials of witches, sinners, or those who died unnaturally, transforming into blood-feeding revenants that rise from graves to drain the life force of the living. This monstrous figure sustains itself by sucking blood from humans or animals, spreading misfortune and death in nocturnal raids, distinct from benevolent spirits in its unrelenting predatory drive. Destruction typically involves burning the body or staking it through the heart, drawing from folk rituals fused with Islamic purification methods in Turkish beliefs.[73][79]Mythical Guardians and Hybrids

In Turkish folklore, mythical guardians and hybrids often embody protective yet ambiguous roles, blending animalistic traits with supernatural abilities to safeguard natural realms or treasures while challenging human intruders. These entities, rooted in pre-Islamic Turkic and Central Asian traditions, frequently appear in epics and oral narratives, reflecting shamanistic influences where spirits mediate between the human and natural worlds.[80] The peri are winged fairy-like beings derived from pre-Islamic Persian-influenced lore that permeated Turkish mythology, often depicted as benevolent helpers who reside in remote mountains and interact with humans through tests of character. In the epic Kitab-i Dede Korkut, a peri warns a shepherd of impending doom if he reveals the secret of his monstrous son's birth, illustrating their role as prophetic guardians who aid heroes but demand moral vigilance.[80] Peris in Turkish tales manifest as ethereal figures flying with green, cloud-like garments or in the form of doves, capable of granting wishes to the worthy while punishing the deceitful, thus serving as ambiguous protectors of cosmic balance.[81] Their mountain habitats symbolize inaccessibility, where they test human resolve before offering aid, as seen in broader Anatolian variants where peris assist wanderers but vanish if trust is betrayed.[82] Tepegöz, a one-eyed cyclopean giant, functions as a formidable guardian of hidden treasures in Oghuz Turkish lore, though primarily as an antagonist who embodies chaotic destruction. Featured in the eighth tale of the Book of Dede Korkut, Tepegöz is born from the illicit union of a shepherd and a peri, emerging as a monstrous ogre with a single eye in its forehead, terrorizing tribes by devouring villagers and demanding tribute to protect his lair.[83] The hero Basat defeats it by exploiting its vulnerability—plucking or blinding the eye with a heated iron spit—symbolizing the triumph of cunning over primal chaos and underscoring Tepegöz's role as a threshold guardian whose defeat restores communal order.[83] This hybrid figure, blending human and bestial ferocity, draws from ancient Turkic pastoral fears of untamed wilderness, where such beings hoard wealth but invite peril to those who encroach.[80] Yelbeghen represents a wind-associated hybrid spirit from Siberian Turkic and Altai mythology, often portrayed as a multi-headed dragon or serpent-rider that aids shamans while ferrying souls across ethereal realms. Etymologically linked to "yel" (wind or magic), Yelbeghen appears in ancient Altai legends as a seven-headed ogre capable of devouring celestial bodies like the sun and moon during eclipses, yet it also serves as a shamanic ally, carrying spirits on gusts or manifesting as a horse-like rider to guide rituals. In Central Asian art and oral traditions, it is depicted with serpentine bodies and rider forms, protecting sacred winds but misleading the unworthy, reflecting its dual role in shamanistic practices where wind spirits bridge the living and ancestral worlds.[84] The archura is a shapeshifting forest guardian in Volga-Ural Turkic folklore, particularly among Tatar and Chuvash peoples, who protects woodlands and wildlife by misleading intruders with its backward-facing feet and deceptive cries. Typically appearing as a tall, horned figure with hooves, a tail, and a beard of grass, the archura wards off hunters and loggers by altering its size—from blade of grass to towering tree—and leading them astray, only to release them if offerings like tobacco or milk are left as appeasement.[85] Rooted in pre-Christian beliefs, it embodies the forest's autonomy, demanding respect through rituals to prevent harm to its domain, as detailed in ethnographic studies of regional encounters where humans invoke it for safe passage.[86]Regional Variations

Black Sea Region Customs

The Black Sea region of Turkey, encompassing provinces such as Trabzon, Rize, and Giresun, features a rich tapestry of folklore shaped by its rugged coastline, dense forests, and agricultural heritage, where maritime influences blend with ancient rural practices passed down through generations. These customs often reflect a deep connection to nature, community resilience, and protective rituals against misfortune, distinct from the inland traditions of other Anatolian areas. Ethnographic studies highlight how these practices persist in rural communities, emphasizing harmony with the environment and social bonds during life events like weddings and healing ceremonies.[87] Tree worship remains a prominent element of Black Sea folklore, rooted in pre-Islamic Turkic shamanistic beliefs, with sacred groves of beech trees (Fagus orientalis) serving as sites for communal reverence and personal supplications. In these groves, particularly in the Pontic highlands, devotees tie colorful ribbons or strips of cloth to the branches of ancient beeches while voicing wishes for health, fertility, or prosperity, a tradition linked to ancient Pontic animistic views of trees as intermediaries between the earthly and divine realms. This ritual echoes broader Turkic mythology where the beech symbolizes the Tree of Life, connecting universes and facilitating spiritual communication.[88][89]Central and Eastern Anatolian Legends

Central and Eastern Anatolian folklore is characterized by epic narratives and mystical tales that reflect the rugged landscapes and historical migrations of inland Turkey, emphasizing themes of heroism, spiritual protection, and harmony with nature. These stories, often transmitted orally among Turkic communities, draw from Oghuz traditions and blend Islamic influences with pre-Islamic shamanistic elements, particularly in regions like Cappadocia and Erzurum where arid terrains and ancient rock formations inspire lore of quests and supernatural encounters.[90][91] The Dede Korkut epic, a cornerstone of Turkish oral literature, influences storytelling in Eastern Anatolia, with its twelve heroic tales incorporating themes of mountain quests where protagonists navigate treacherous peaks in search of lost kin or honor. These narratives highlight wolf totems as sacred guides and ancestral symbols, portraying wolves as protective spirits that lead Oghuz warriors through harsh terrains, echoing the epic's origins among nomadic Turkic tribes. Such motifs underscore resilience against environmental and tribal challenges, with narratives like those of Basat or Bamsi Beyrek reimagined to include local mountain passes as sites of divine intervention.[90][92][93] Battal Gazi legends center on the 8th-century Umayyad warrior-saint Seyyid Battal Gazi, who is depicted as a fearless fighter against Byzantine forces in Anatolia, his exploits evolving into miracle tales of divine aid during battles and conversions. These stories blend historical raids with hagiographic elements, such as Battal Gazi's tomb in Seyitgazi (near Eskişehir) serving as a shrine where pilgrims seek blessings for protection and healing. The Battalname epic portrays him summoning supernatural allies to topple fortresses, symbolizing the gazi ethos of frontier jihad and cultural synthesis in Central Anatolia.[94][95][96] In Cappadocian lore, the fairy chimneys—tall, conical rock formations shaped by erosion—are believed to be homes of peri, ethereal fairy-like beings who dwell in their peaks and caverns, guarding hidden realms from intruders. Local tales describe these structures as portals where peri interact with humans, offering wisdom or curses, while the region's underground cities like Derinkuyu served as refuges from demons (cin) during ancient invasions, with folklore recounting how communities sealed entrances to evade malevolent spirits lurking in the darkness. These narratives, tied to the area's volcanic geology, emphasize themes of concealment and mystical guardianship, with peri often mediating between the earthly and otherworldly.[97][98][99] Alevi semah dances in Sivas represent circular rituals performed during cem gatherings, where participants form interlocking rings to symbolize unity and cosmic harmony, invoking Hızır—the evergreen saint of aid and renewal—for protection amid the region's severe winters. These movements, accompanied by saz music and poetic invocations, enact a spiritual journey to transcend hardship, with Hızır invoked as a winter savior who brings vitality to frozen lands and shields against peril. Rooted in Alevi-Bektaşi traditions, semah in Sivas adapts to seasonal cycles, intensifying during cold months to foster communal resilience and divine intercession.[100][101][102]References

- https://www.[academia.edu](/page/Academia.edu)/11926114/2_articles_Shamanism_in_Turkey_bards_masters_of_the_jinns_and_healers_and_The_Bektashi_Alevi_dance_of_the_cranes_in_Turkey_a_shamanic_heritage

- https://folklore.usc.edu/cin-turkish-demons/