Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Vettones

View on Wikipedia

The Vettones (Greek: Ouettones) were an Iron Age pre-Roman people of the Iberian Peninsula.[1][2]

Origins

[edit]Lujan (2007) concludes that some of the names of the Vettones show clearly western Hispano-Celtic features.[3] A Celtiberian origin has also been claimed.[1] Organized since the 3rd Century BC, the Vettones formed a tribal confederacy of undetermined strength. Even though their tribes' names are obscure, the study of local epigraphic evidence has identified the Calontienses, Coerenses, Caluri, Bletonesii[4][5] and Seanoci,[6] but the others remain unknown.

Culture

[edit]

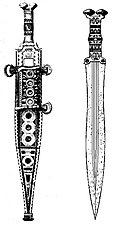

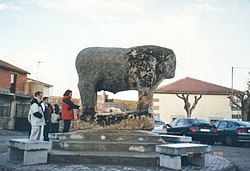

A predominately horse-[7] and cattle-herder people that practiced transhumance, archeology has identified them with the local 2nd Iron Age ‘Cogotas II’ Culture, also known as the ‘Culture of the Verracos’ (verracos de piedra), named after the crude granite sculptures representing pigs, wild boars and bulls that still dot their former region. These are one of their most notable enduring legacies today, the other possibly being the game of Calva, which dates to the time of their influence. The Iron Age sites and respective cemeteries of Las Cogotas, La Osera, El Raso de Candeleda, La Mesa de Miranda, Yecla la Vieja, El Castillo, Las Merchanas and Alcántara have provided enough elements – weapons, shields, fibulae, belt buckles, bronze cauldrons, Campanian and Greek pottery – which attest the strong contacts with the Pellendones of the eastern meseta, the Iberian south and the Mediterranean.

Location

[edit]

The Vettones lived in the western part of the meseta—the high central upland plain of the Iberian Peninsula—the region where the modern Spanish provinces of Ávila and Salamanca are today, as well as parts of Zamora, Toledo, Cáceres and also the eastern border areas of modern Portuguese territory. Their own capital city, which the ancient sources mysteriously failed to mention at all, has not yet been found though other towns mentioned by Ptolemy[8] were located, such as Capara (Ventas de Cápara), Obila (Ávila?), Mirobriga (Ciudad Rodrigo?), Turgalium (Trujillo, Cáceres), Alea (Alía – Cáceres) and probably Bletisa/Bletisama (Ledesma, Salamanca).[9][10] Other probable Vettonian towns were Tamusia (Villasviejas de Tamuja, near Botija, Cáceres; Celtiberian-type mint: Tamusiensi), Ocelon / Ocelum (Castelo Branco), Cottaeobriga (Almeida) and Lancia (Serra d’Opa).

History

[edit]

Traditional allies of the Lusitani, the Vettones helped the latter in their struggle against the advancing Carthaginians led by Hasdrubal the Fair and Hannibal in the late 3rd century BC. At first placed under nominal Punic suzerainty by the time of the Second Punic War, the Vettones threw off their yoke soon after 206 BC. However, a mercenary contingent of Vettones accompanied Hannibal on his march to Italy, led by the chieftain Balarus.[11] At the Lusitanian Wars of the 2nd century BC they joined once again the Lusitani under Punicus, Caesarus and Caucenus in their attacks on Baetica, Carpetania, the Cyneticum and the failed incursion on the North African town of Ocilis (modern Asilah, Morocco) in 153 BC.[12][13]

Although technically incorporated around 134-133 BC into Hispania Ulterior, the Vettones continued to raid the more romanized regions further south and during the Roman civil wars of the early 1st century BC, they sided with Quintus Sertorius. In 79 BC, Proconsul Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius attempted to methodically secure the cities and tribes of central Hispania by establishing fortified bases for his military operations in Vettonia, mainly at Metellinum (Medellín), Castra Caecilia (Cáceres el Viejo), and Viccus Caecilius (somewhere in the Sierra de Gredos), but this did not prevented the Vettones from providing auxiliary troops to Sertorius' army in 77-76 BC.[14] Crushed by the provincial Propraetor Julius Caesar in 61 BC, they later rose in support of Pompey's faction and fought at the battle of Munda (Montilla – Córdoba) in Baetica.[15]

Romanization

[edit]In the 1st Century BC, the Romans began to establish military colonies throughout Vettonia, first at Kaisarobriga or Caesarobriga (Talavera de la Reina – Toledo) and Norba Caesarina (near Cáceres), latter followed by Metellinum (Medellín), and in around 27-13 BC the Vettones were aggregated to the newly created Roman province of Lusitania with Emerita Augusta (Mérida) as the capital of the new province.[16]

Despite their progressive assimilation into the Roman world, the Vettones managed to retain their martial traditions, which enabled them to provide the Roman Army with an auxiliary cavalry unit (Ala), the Ala Hispanorum Vettonum Civium Romanorum, which participated in Emperor Claudius' invasion of Britain in AD 43–60.[17]

Namesake

[edit]The Vettones are not to be confused with the Vettonenses, inhabitants of Vettona (today's Bettona) in Umbria.

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Álvarez-Sanchís, Jesús R. (2005). "Oppida and Celtic society in western Spain". e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies, Vol. 6 (The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula).

- ^ Cremin, The Celts in Europe (1992), p. 57.

- ^ Wodtko, Dagmar S. (2010). "Chapter 11: The Problem of Lusitanian". In Cunliffe, Barry; Koch, John T. (eds.). Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language and Literature. Celtic Studies Publications. Oxford: Oxbow Books. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.: 360–361 Reissued in 2012 in softcover as ISBN 978-1-84217-475-3.

- ^ Conrad Cichorius, Römische Studien (Berlin, 1922).

- ^ Plutarch, Quaestiones Romanes, question 83.

- ^ Edmondson, "A criação de uma sociedade provincial romana" (2022), p. 36.

- ^ Silius Italicus, Punica, III, 378.

- ^ Ptolemy, Geographiké Hyphegésis, II, 5, 7.

- ^ Conrad Cichorius, Römische Studien (Berlin, 1922).

- ^ Plutarch, Quaestiones Romanes, question 83.

- ^ Silius Italicus, Punica, III, 378-414.

- ^ Appian, Iberiké, 57.

- ^ Livy, Periochae, 47.

- ^ Matyszak, Sertorius and the struggle for Spain (2013), pp. 79; 144.

- ^ Caesar, De Bello Civili, I, 38, 1-4.

- ^ Garcia y Bellido, Antonio (1958). Las colonias romanas de la provincia Lusitania (PDF). Antigua: Historia y Arqueología de las civilizaciones. pp. 3, 4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ "El caballo en la sociedad celtibérica". 24 September 2015.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aedeen Cremin, The Celts in Europe, Sydney, Australia: Sydney Series in Celtic Studies 2, Centre for Celtic Studies, University of Sydney (1992) ISBN 0-86758-624-9

- Ángel Montenegro et alii, Historia de España 2 - colonizaciones y formación de los pueblos prerromanos (1200-218 a.C), Editorial Gredos, Madrid (1989) ISBN 84-249-1386-8

- Christophe Bonnaud, Les castros vettons et leurs populations au Second Âge du Fer (Ve siècle-IIe siècle avant J.-C.), I: implantation et systèmes défensives in Revista Portuguesa de Arqueologia, pp. 209–242, volume 8, número 1, IPA Lisboa (2005) ISSN 0874-2782

- Christophe Bonnaud, Les castros vettons et leurs populations au Second Âge du Fer (Ve siècle-IIe siècle avant J.-C.), II: l’habitat, l’économie, la société in Revista Portuguesa de Arqueologia, pp. 209–242, volume 8, número 2, IPA Lisboa (2005) ISSN 0874-2782

- Eduardo Sánchez Moreno, Vetones: Historia y Arqueología de un pueblo prerromano, Ediciones de la Universidad Autónoma, Madrid (2000) ISBN 84-7477-759-3

- Francisco Burillo Mozota, Los Celtíberos, etnias y estados, Crítica, Grijalbo Mondadori, S.A., Barcelona (1998, revised edition 2007) ISBN 84-7423-891-9

- Isabel Baquedano Beltrán, La necrópolis vettona de La Osera (Chamartín, Ávila, España) – volumen I, Zona Arqueológia número 19-I, Museo Arqueológico Regional, Alcalá de Henares (2016) ISBN 978-84-451-3518-1

- Isabel Baquedano Beltrán, La necrópolis vettona de La Osera (Chamartín, Ávila, España) – volumen II, Zona Arqueológia número 19-II, Museo Arqueológico Regional, Alcalá de Henares (2016) ISBN 978-84-451-3518-1

- Manuel Salinas de Frías, Los vettones: indigenismo y romanización en el occidente de la meseta, Ediciones Universidad Salamanca, Salamanca (2001) ISBN 84-7800-881-0

- Martín Almagro-Gorbea & Ana Maria Martín, Castros y Oppida en Extremadura, Editorial Complutense, Madrid (1994) ISBN 84-7491-533-3

- Jesús R. Álvarez-Sanchís, Los vettones, Real Academia de la Historia, Madrid (2003) ISBN 9788495983169

- Jesús R. Álvarez-Sanchís, Los señores del ganado – Arqueología de los pueblos prerromanos en el occidente de Iberia, Colección Arqueología, Editorial Akal, Madrid (2003) ISBN 84-460-1650-8

- Jonathan Edmondson, "A criação de uma sociedade provincial romana" in A Lusitânia Romana: fronteira do mundo antigo, National Geographic História, edição especial, RBA Revistas S.L., Barcelona (2022), pp. 34-43. ISSN 2696-7979

- Philip Matyszak, Sertorius and the struggle for Spain, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley (2013) ISBN 978-1-84884-787-3

Further reading

[edit]- Barry Cunliffe, The Celts – A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press (2003) ISBN 0-19-280418-9.

- Dáithí Ó hÓgáin, The Celts: A History, The Collins Press, Cork (2002) ISBN 0-85115-923-0

- Daniel Varga, The Roman Wars in Spain: The Military Confrontation with Guerrilla Warfare, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley (2015) ISBN 978-1-47382-781-3

- Leonard A Curchin (5 May 2004). The Romanization of Central Spain: Complexity, Diversity and Change in a Provincial Hinterland. Routledge. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-1-134-45112-8.

- Ludwig Heinrich Dyck, The Roman Barbarian Wars: The Era of Roman Conquest, Author Solutions (2011) ISBNs 1426981821, 9781426981821

- Luis Silva, Viriathus and the Lusitanian resistance to Rome 155-139 BC, Pen & Sword Military, Barnsley (2013) ISBN 978-1-78159-128-4

- John T. Koch (ed.), Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO Inc., Santa Barbara, California (2006) ISBN 1-85109-440-7, 1-85109-445-8