Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

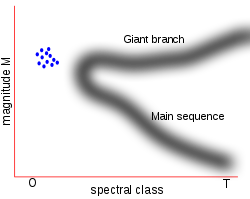

Blue straggler

View on Wikipedia

A blue straggler is a type of star that is more luminous and bluer than expected. Typically identified in a stellar cluster, they have a higher effective temperature than the main sequence turnoff point for the cluster, where ordinary stars begin to evolve towards the red giant branch. Blue stragglers were first discovered by Allan Sandage in 1953 while performing photometry of the stars in the globular cluster M3.[1][2]

Description

[edit]Standard theories of stellar evolution hold that the position of a star on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram should be determined almost entirely by the initial mass of the star and its age. In a cluster, stars all formed at approximately the same time, and thus in an H–R diagram for a cluster, all stars should lie along a clearly defined curve set by the age of the cluster, with the positions of individual stars on that curve determined solely by their initial mass. With masses two to three times that of the rest of the main-sequence cluster stars, blue stragglers seem to be exceptions to this rule.[3] The resolution of this problem is likely related to interactions between two or more stars in the dense confines of the clusters in which blue stragglers are found. Blue stragglers are also found among field stars, although their detection is more difficult to disentangle from genuine massive main sequence stars. Field blue stragglers can however be identified in the Galactic halo, since all surviving main sequence stars are low mass.[4]

Formation

[edit]

Several explanations have been put forth to explain the existence of blue stragglers. The simplest is that blue stragglers formed later than the rest of the stars in the cluster, but evidence for this is limited.[6] Another simple proposal is that blue stragglers are either field stars which are not actually members of the clusters to which they seem to belong, or are field stars which were captured by the cluster. This too seems unlikely, as blue stragglers often reside at the very center of the clusters to which they belong. The most likely explanation is that blue stragglers are the result of stars that come too close to another star or similar mass object and collide.[7] The newly formed star has thus a higher mass, and occupies a position on the HR diagram which would be populated by genuinely young stars.

Cluster interactions

[edit]The two most viable explanations put forth for the existence of blue stragglers both involve interactions between cluster members. One explanation is that they are current or former binary stars that are in the process of merging or have already done so. The merger of two stars would create a single more massive star, potentially with a mass larger than that of stars at the main-sequence turn-off point. While a star born with a mass larger than that of stars at the turn-off point would evolve quickly off the main sequence, the components forming a more massive star (via merger) would thereby delay such a change. There is evidence in favor of this view, notably that blue stragglers appear to be much more common in dense regions of clusters, especially in the cores of globular clusters. Since there are more stars per unit volume, collisions and close encounters are far more likely in clusters than among field stars and calculations of the expected number of collisions are consistent with the observed number of blue stragglers.[7]

One way to test this hypothesis is to study the Stellar pulsation of variable blue stragglers. The asteroseismological properties of merged stars may be measurably different from those of typical pulsating variables of similar mass and luminosity. However, the measurement of pulsations is very difficult, given the scarcity of variable blue stragglers, the small photometric amplitudes of their pulsations and the crowded fields in which these stars are often found. Some blue stragglers have been observed to rotate quickly, with one example in 47 Tucanae observed to rotate 75 times faster than the Sun, which is consistent with formation by collision.[9]

The other explanation relies on mass transfer between two stars born in a binary star system. The more massive of the two stars in the system will evolve first and as it expands, will overflow its Roche lobe. Mass will quickly transfer from the initially more massive companion onto the less massive; like the collision hypothesis, this would explain why there are main-sequence stars more massive than other stars in the cluster which have already evolved off the main sequence.[10] Observations of blue stragglers have found that some have significantly less carbon and oxygen in their photospheres than is typical, which is evidence of their outer material having been dredged up from the interior of a companion.[11][12]

Overall, there is evidence in favor of both collisions and mass transfer between binary stars.[13] In M3, 47 Tucanae, and NGC 6752, both mechanisms seem to be operating, with collisional blue stragglers occupying the cluster cores and mass transfer blue stragglers at the outskirts.[14] The discovery of low-mass white dwarf companions around two blue stragglers in the Kepler field suggests these two blue stragglers gained mass via stable mass transfer.[15]

Field formation

[edit]

Blue stragglers are also found among field stars, as a result of close binary interaction. Since the fraction of close binaries increases with decreasing metallicity, blue stragglers are increasingly likely to be found across metal poor stellar populations. The identification of blue stragglers among field stars however is more difficult than in stellar clusters, because of the mix of stellar ages and metallicities among field stars. Field blue stragglers however can be identified among old stellar populations, like the Galactic halo, or dwarf galaxies.[4]

Red and yellow stragglers

[edit]"Yellow stragglers" or "red stragglers" are stars with colors between that of the turnoff and the red-giant branch but brighter than the subgiant branch. Such stars have been identified in open and globular star clusters. These stars may be former blue straggler stars that are now evolving toward the giant branch.[16]

See also

[edit]- Algol variable – Class of eclipsing binary stars

- SX Phoenicis variable – Type of variable star

References

[edit]- ^ Sandage, Allan (1953). "The color-magnitude diagram for the globular cluster M3". The Astronomical Journal. 58: 61–75. Bibcode:1953AJ.....58...61S. doi:10.1086/106822.

- ^ John Noble Wilford (1991-08-27). "Cannibal Stars Find a Fountain of Youth". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (2000-06-22). "Blue Stragglers in NGC 6397". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ a b Casagrande, Luca (2020-06-10). "Connecting the Local Stellar Halo and Its Dark Matter Density to Dwarf Galaxies via Blue Stragglers". The Astrophysical Journal. 896 (1): 26. arXiv:2005.09131. Bibcode:2020ApJ...896...26C. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab929f. hdl:1885/268844. ISSN 1538-4357. S2CID 218684551.

- ^ "Too Close for Comfort". Hubble Site. NASA. August 7, 2003. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ^ a b "NASA's Hubble Space Telescope Finds "Blue Straggler" Stars in the Core of a Globular Cluster". Hubble News Desk. 1991-07-24. Retrieved 2006-05-24.

- ^ a b Leonard, Peter J. T. (1989). "Stellar collisions in globular clusters and the blue straggler problem". The Astronomical Journal. 98: 217–226. Bibcode:1989AJ.....98..217L. doi:10.1086/115138.

- ^ "Young Stars at Home in an Ancient Cluster". ESA/Hubble Picture of the Week. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ "Hubble Catches up with a Blue Straggler Star". Hubble News Desk. 1997-10-29. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ^ Shu, Frank (1982). The Physical Universe. University Science Books. ISBN 978-0-935702-05-7.

- ^ "Origin of Strange 'Blue Straggler' Stars Pinned Down". Space.com. 2006-10-05. Retrieved 2014-03-23.

- ^ Ferraro, F. R.; Sabbi, E.; Gratton, R.; Piotto, G.; Lanzoni, B.; Carretta, E.; Rood, R. T.; Sills, A.; Fusi Pecci, F.; Moehler, S.; Beccari, G.; Lucatello, S.; Compagni, N. (2006-08-10). "Discovery of Carbon/Oxygen-depleted Blue Straggler Stars in 47 Tucanae: The Chemical Signature of a Mass Transfer Formation Process". The Astrophysical Journal. 647 (1): L53–L56. arXiv:astro-ph/0610081. Bibcode:2006ApJ...647L..53F. doi:10.1086/507327. S2CID 119450832.

- ^ Nancy Atkinson (2009-12-23). "Blue Stragglers Can Be Either Vampires or Stellar Bad Boys". Universe Today. Retrieved 2010-01-18.

- ^ Mapelli, M.; et al. (2006). "The radial distribution of blue straggler stars and the nature of their progenitors". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 373 (1): 361–368. arXiv:astro-ph/0609220. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.373..361M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11038.x. S2CID 14214665.

- ^ Di Stefano, Rosanne (2010). "Transits and Lensing by Compact Objects in the Kepler Field: Disrupted Stars Orbiting Blue Stragglers". The Astronomical Journal. 141 (5): 142. arXiv:1002.3009. Bibcode:2011AJ....141..142D. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/141/5/142. S2CID 118647532.

- ^ Clark, L. Lee; et al. (2004). "The Blue Straggler and Main-Sequence Binary Population of the low-mass globular cluster Palomar 13". The Astronomical Journal. 128 (6): 3019–3033. arXiv:astro-ph/0409269. Bibcode:2004AJ....128.3019C. doi:10.1086/425886. S2CID 16494169.