Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Q star.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Q star

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

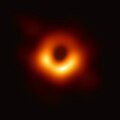

A Q-star, also known as a grey hole, is a hypothetical type of compact, heavy neutron star with an exotic state of matter. Such a star can be smaller than the progenitor star's Schwarzschild radius and have a gravitational pull so strong that some light, but not all light, can escape.[1] Light going in the opposite direction of the star’s center would be the most likely to escape from it, while light going in a direction almost parallel to its surface is the most likely not to escape. The Q stands for a conserved particle number. A Q-star may be mistaken for a stellar black hole.[2] Some stellar black holes might be grey holes, two of which are V404 Cygni and Cygnus X-1. [1]

Types of Q-stars

[edit]- Q-ball[3]

- B-ball, stable Q-balls with a large baryon number B. They may exist in neutron stars that have absorbed Q-ball(s).[3]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Brecher, K. (1993-05-01). "Gray Holes". American Astronomical Society Meeting Abstracts #182. 182: 55.07. Bibcode:1993AAS...182.5507B.

- ^ *Miller, J. C.; Shahbaz, T.; Nolan, L. A. (1998). "Are Q-stars a serious threat for stellar-mass black hole candidates?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 294 (2): L25 – L29. arXiv:astro-ph/9708065. Bibcode:1998MNRAS.294L..25M. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.1998.01384.x.

- ^ a b Kusenko, Alexander (2006). Properties and signatures of supersymmetric Q-balls. workshop on Exotic Physics with Neutrino Telescopes. Uppsala, Sweden. arXiv:hep-ph/0612159. Bibcode:2006hep.ph...12159K.

Further reading

[edit]- Abramowicz, M. A.; Kluźniak, W.; Lasota, J.-P. (2002). "No observational proof of the black-hole event-horizon". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 396 (3): L31 – L34. arXiv:astro-ph/0207270. Bibcode:2002A&A...396L..31A. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021645. S2CID 9771972.

Q star

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

A Q star, also known as a strange star or grey hole, is a hypothetical type of compact star composed of strange quark matter, an exotic state where up, down, and strange quarks are deconfined under extreme densities.[1] Predicted by the strange quark matter hypothesis, Q stars could form through the conversion of a neutron star core when densities exceed about 5–10 times nuclear density, leading to a phase transition from hadronic to quark matter.[2]

Unlike neutron stars, which are supported against gravitational collapse by neutron degeneracy pressure, Q stars are self-bound by the strong nuclear force, resulting in greater compactness (radii potentially below 10 km for solar masses around 1.4 M⊙) and stability up to higher masses (possibly exceeding 2 M⊙) without forming black holes.[3] Their surfaces would consist of bare quark matter, potentially explaining observed anomalies in some pulsars, such as rapid cooling or high densities, though no conclusive evidence exists as of November 2025.[4]