Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aargau

View on Wikipedia

Aargau (/ˈɑːrɡaʊ/ AR-gow, Swiss Standard German: [ˈaːrɡaʊ] ⓘ), more formally[4] the Canton of Aargau (German: Kanton Aargau; Romansh: Chantun Argovia; French: Canton d'Argovie; Italian: Canton Argovia), is one of the 26 cantons forming the Swiss Confederation. It is composed of eleven districts and its capital is Aarau.

Key Information

Aargau is one of the most northerly cantons of Switzerland, by the lower course of the Aare River, which is why it is called Aar-gau ("Aare province"). It is one of the most densely populated regions of Switzerland.[5]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The area of Aargau and the surrounding areas were controlled by the Helvetians, a tribe of Celts, as far back as 200 BC.[6] It was eventually occupied by the Romans and then by the 6th century, the Franks.[7] The Romans built a major settlement called Vindonissa, near the present location of Brugg.[6]

Medieval Aargau

[edit]

The reconstructed Old High German name of Aargau is Argowe, first unambiguously attested (in the spelling Argue) in 795. The term described a territory only loosely equivalent to that of the modern canton, including the region between Aare and Reuss rivers, including Pilatus and Napf, i.e. including parts of the modern cantons of Bern (Bernese Aargau, Emmental, parts of the Bernese Oberland), Solothurn, Basel-Landschaft, Lucerne, Obwalden and Nidwalden, but not the parts of the modern canton east of the Reuss (Baden District), which were part of Zürichgau.

Within the Frankish Empire (8th to 10th centuries), the area was a disputed border region between the duchies of Alamannia and Burgundy. A line of the von Wetterau (Conradines) intermittently held the countship of Aargau from 750 until about 1030, when they lost it (having in the meantime taken the name von Tegerfelden). This division became the ill-defined (and sparsely settled) outer border of the early Holy Roman Empire at its formation in the second half of the 10th century. Most of the region came under the control of the ducal house of Zähringen and the comital houses of Habsburg and Kyburg by about 1200.

In the second half of the 13th century, the territory became divided between the territories claimed by the imperial cities of Bern, Lucerne and Solothurn and the Swiss canton of Unterwalden. The remaining portion, largely corresponding to the modern canton of Aargau, remained under the control of the Habsburgs until the "conquest of Aargau" by the Old Swiss Confederacy in 1415.[8] Habsburg Castle itself, the original seat of the House of Habsburg, was taken by Bern in April 1415.[9] The Habsburgs had founded a number of monasteries (with some structures enduring, e.g., in Wettingen and Muri), the closing of which by the government in 1841 was a contributing factor to the outbreak of the Swiss civil war – the "Sonderbund War" – in 1847.

Under the Swiss Confederation

[edit]

When Frederick IV of Habsburg sided with Antipope John XXIII at the Council of Constance, Emperor Sigismund placed him under the Imperial ban.[nb 1] In July 1414, the Pope visited Bern and received assurances from them, that they would move against the Habsburgs.[10] A few months later the Swiss Confederation denounced the Treaty of 1412. Shortly thereafter in 1415, Bern and the rest of the Swiss Confederation used the ban as a pretext to invade the Aargau. The Confederation was able to quickly conquer the towns of Aarau, Lenzburg, Brugg and Zofingen along with most of the Habsburg castles. Bern kept the southwest portion (Zofingen, Aarburg, Aarau, Lenzburg, and Brugg), northward to the confluence of the Aare and Reuss.[10] The important city of Baden was taken by a united Swiss army and governed by all 8 members of the Confederation.[10] Some districts, named the Freie Ämter (free bailiwicks) – Mellingen, Muri, Villmergen, and Bremgarten, with the countship of Baden – were governed as "subject lands" by all or some of the Confederates. Shortly after the conquest of the Aargau by the Swiss, Frederick humbled himself to the Pope. The Pope reconciled with him and ordered all of the taken lands to be returned. The Swiss refused and years later after no serious attempts at re-acquisition, the Duke officially relinquished rights to the Swiss.[11]

Unteraargau or Berner Aargau

[edit]

Bern's portion of the Aargau came to be known as the Unteraargau, though can also be called the Berner or Bernese Aargau. In 1514 Bern expanded north into the Jura and so came into possession of several strategically important mountain passes into the Austrian Fricktal. This land was added to the Unteraargau and was directly ruled from Bern. It was divided into seven rural bailiwicks and four administrative cities, Aarau, Zofingen, Lenzburg and Brugg. While the Habsburgs were driven out, many of their minor nobles were allowed to keep their lands and offices, though over time they lost power to the Bernese government. The bailiwick administration was based on a very small staff of officials, mostly made up of Bernese citizens, but with a few locals.[12]

When Bern converted during the Protestant Reformation in 1528, the Unteraargau also converted. At the beginning of the 16th century a number of Anabaptistss migrated into the upper Wynen and Rueder valleys from Zürich. Despite pressure from the Bernese authorities in the 16th and 17th centuries, Anabaptism never entirely disappeared from the Unteraargau.[12]

Bern used the Aargau bailiwicks mostly as a source of grain for the rest of the city-state. The administrative cities remained economically only of regional importance. However, in the 17th and 18th centuries Bern encouraged industrial development in Unteraargau and by the late 18th century it was the most industrialized region in the city-state. The high industrialization led to high population growth in the 18th century, for example between 1764 and 1798, the population grew by 35%, far more than in other parts of the canton. In 1870 the proportion of farmers in Aarau, Lenzburg, Kulm, and Zofingen districts was 34–40%, while in the other districts it was 46–57%.[12]

Freie Ämter

[edit]

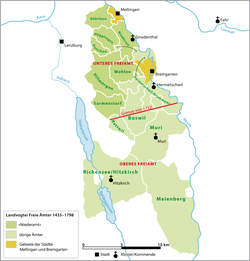

The rest of the Freie Ämter were collectively administered as subject territories by the rest of the Confederation. Muri Amt was assigned to Zürich, Lucerne, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug and Glarus, while the Ämter of Meienberg, Richensee and Villmergen were first given to Lucerne alone. The final boundary was set in 1425 by an arbitration tribunal and Lucerne had to give the three Ämter to be collectively ruled.[13] The four Ämter were then consolidated under a single Confederation bailiff into what was known in the 15th century as the Waggental Bailiwick (German: Vogtei im Waggental). In the 16th century, it came to be known as the Vogtei der Freien Ämter. While the Freien Ämter often had independent lower courts, they were forced to accept the Confederation's sovereignty. Finally, in 1532, the canton of Uri became part of the collective administration of the Freien Ämter.[14]

At the time of the Protestant Reformation, the majority of the Ämter converted to the new faith. In 1529, a wave of iconoclasm swept through the area and wiped away much of the old religion. After the defeat of Zürich in the second Battle of Kappel in 1531, the victorious five Catholic cantons marched their troops into the Freie Ämter and reconverted them to Catholicism.[13]

In the First War of Villmergen, in 1656, and the Toggenburg War (or Second War of Villmergen), in 1712, the Freie Ämter became the staging ground for the warring Reformed and Catholic armies. While the peace after the 1656 war did not change the status quo, the fourth Peace of Aarau in 1712 brought about a reorganization of power relations. The victory gave Zürich the opportunity to force the Catholic cantons out of the government in the county of Baden and the adjacent area of the Freie Ämter. The Freie Ämter were then divided in two by a line drawn from the gallows in Fahrwangen to the Oberlunkhofen church steeple. The northern part, the so-called Unteren Freie Ämter (lower Freie Ämter), which included the districts of Boswil (in part) and Hermetschwil and the Niederamt, were ruled by Zürich, Bern and Glarus. The southern part, the Oberen Freie Ämter (upper Freie Ämter), were ruled by the previous seven cantons but Bern was added to make an eighth.[13]

During the Helvetic Republic (1798–1803), the county of Baden, the Freie Ämter and the area known as the Kelleramt were combined into the canton of Baden.

County of Baden

[edit]

The County of Baden was a shared condominium of the entire Old Swiss Confederacy. After the Confederacy conquest in 1415, they retained much of the Habsburg legal structure, which caused a number of problems. The local nobility had the right to hold the low court in only about one fifth of the territory. There were over 30 different nobles who had the right to hold courts scattered around the surrounding lands. All these overlapping jurisdictions caused numerous conflicts, but gradually the Confederation was able to acquire these rights in the county. The cities of Baden, Bremgarten and Mellingen became the administrative centers and held the high courts. Together with the courts, the three administrative centers had considerable local autonomy, but were ruled by a governor who was appointed by the Acht Orte every two years. After the Protestant victory at the Second Battle of Villmergen, the administration of the County changed slightly. Instead of the Acht Orte appointing a bailiff together, Zürich and Bern each appointed the governor for 7 out of 16 years while Glarus appointed him for the remaining two years.[15]

The chaotic legal structure and fragmented land ownership combined with a tradition of dividing the land among all the heirs in an inheritance prevented any large scale reforms. The governor tried in the 18th century to reform and standardize laws and ownership across the county, but with limited success. With an ever-changing administration, the County lacked a coherent long-term economic policy or support for reforms. By the end of the 18th century there were no factories or mills and only a few small cottage industries along the border with Zürich. Road construction first became a priority after 1750, when Zürich and Bern began appointing a governor for seven years.[15]

During the Protestant Reformation, some of the municipalities converted to the new faith. However, starting in 1531, some of the old parishes were converted back to the old faith. The governors were appointed from both Catholic and Protestant cantons and since they changed every two years, neither faith gained a majority in the county.[15]

After the French invasion, on 19 March 1798, the governments of Zürich and Bern agreed to the creation of the short lived canton of Baden in the Helvetic Republic. With the Act of Mediation in 1803, the canton of Baden was dissolved. Portions of the lands of the former County of Baden now became the District of Baden in the newly created canton of Aargau. After World War II, this formerly agrarian region saw striking growth and became the district with the largest and densest population in the canton (110,000 in 1990, 715 persons per km2).[15]

Forming the canton of Aargau

[edit]

The contemporary canton of Aargau was formed in 1803, a canton of the Swiss Confederation as a result of the Act of Mediation. It was a combination of three short-lived cantons of the Helvetic Republic: Aargau (1798–1803), Baden (1798–1803) and Fricktal (1802–1803). Its creation is therefore rooted in the Napoleonic era. In the year 2003, the canton of Aargau celebrated its 200th anniversary.

French forces occupied the Aargau from 10 March to 18 April 1798; thereafter the Bernese portion became the canton of Aargau and the remainder formed the canton of Baden. Aborted plans to merge the two halves came in 1801 and 1802, and they were eventually united under the name Aargau,[5][16] which was then admitted as a full member of the reconstituted Confederation following the Act of Mediation. Some parts of the canton of Baden at this point were transferred to other cantons: the Amt of Hitzkirch to Lucerne, whilst Hüttikon, Oetwil an der Limmat, Dietikon and Schlieren went to Zürich. In return, Lucerne's Amt of Merenschwand was transferred to Aargau (district of Muri).

The Fricktal, ceded in 1802 by Austria via Napoleonic France to the Helvetic Republic, was briefly a separate canton of the Helvetic Republic (the canton of Fricktal) under a Statthalter ('Lieutenant'), but on 19 March 1803 (following the Act of Mediation) was incorporated into the canton of Aargau.

The former cantons of Baden and Fricktal can still be identified with the contemporary districts – the canton of Baden is covered by the districts of Zurzach, Baden, Bremgarten, and Muri (albeit with the gains and losses of 1803 detailed above); the canton of Fricktal by the districts of Rheinfelden and Laufenburg (except for Hottwil which was transferred to that district in 2010).

Chief magistracy

[edit]The chief magistracy of Aargau changed its style repeatedly:

- first two consecutive Regierungsstatthalter :

- April 1798 – November 1801 Jakob Emmanuel Feer (1754–1833)

- 1802–1803 Johann Heinrich Rothpletz (1766–1833)

- Presidents of the Government Commission

- 10 March 1803 – 26 April 1803 Johann Rudolf Dolder (1753–1807)

- 26 April 1803 – 1815 a 'Small Council' (president rotating monthly)

- annual Amtsbürgermeister 1815–1831

- annual Landammänner since 1815

Jewish history in Aargau

[edit]

In the 17th century, Aargau was the only federal condominium where Jews were tolerated. In 1774, they were restricted to just two towns, Endingen and Lengnau. While the rural upper class pressed incessantly for the expulsion of the Jews, the financial interests of the authorities prevented it. They imposed special taxes on peddling and cattle trading, the primary Jewish professions. The Protestant occupiers also enjoyed the discomfort of the local Catholics by the presence of the Jewish community.[17] The Jews were directly subordinate to the governor; from 1696, they were compelled to renew a letter of protection from him every 16 years.[15]

During this period, Jews and Christians were not allowed to live under the same roof, neither were Jews allowed to own land or houses. They were taxed at a much higher rate than others and, in 1712, the Lengnau community was "pillaged."[18] In 1760, they were further restricted regarding marriages and procreation. An exorbitant tax was levied on marriage licenses; oftentimes, they were outright refused.[17] This remained the case until the 19th century. In 1799, the Helvetic republic abolished all special tolls, and, in 1802, removed the poll tax.[18] On 5 May 1809, they were declared citizens and given broad rights regarding trade and farming. They were still restricted to Endingen and Lengnau until 7 May 1846, when their right to move and reside freely within the canton of Aargau was granted. On 24 September 1856, the Swiss Federal Council granted them full political rights within Aargau, as well as broad business rights; however the majority Christian population did not fully abide by these new liberal laws. The time of 1860 saw the canton government voting to grant suffrage in all local rights and to give their communities autonomy. Before the law was enacted, it was however repealed due to vocal opposition led by the Ultramonte Party.[18] Finally, the federal authorities in July 1863, granted all Jews full rights of citizens. However, they did not receive all of the rights in Endingen and Lengnau until a resolution of the Grand Council, on 15 May 1877, granted citizens' rights to the members of the Jewish communities of those places, giving them charters under the names of New Endingen and New Lengnau.[18] The Swiss Jewish Kulturverein was instrumental in this fight from its founding in 1862 until it was dissolved 20 years later.[18] During this period of diminished rights, they were not even allowed to bury their dead in Swiss soil and had to bury their dead on an island called Judenäule (Jews' Isle) on the Rhine near Waldshut.[18] Beginning in 1603, the deceased Jews of the Surbtal communities were buried on the river island which was leased by the Jewish community. As the island was repeatedly flooded and devastated, in 1750 the Surbtal Jews asked the Tagsatzung to establish the Endingen cemetery in the vicinity of their communities.[19][20]

Geography

[edit]

The capital of the canton is Aarau, which is located on its western border, on the Aare. The canton borders Germany (Baden-Württemberg) to the north, the Rhine forming the border. To the west lie the Swiss cantons of Basel-Landschaft, Solothurn and Bern; the canton of Lucerne lies south, and Zürich and Zug to the east. Its total area is 1,404 square kilometers (542 sq mi). Besides the Rhine, it contains two large rivers, the Aare and the Reuss.[7]

The canton of Aargau is one of the least mountainous Swiss cantons, forming part of a great table-land, to the north of the Alps and the east of the Jura, above which rise low hills. The surface of the country is diversified with undulating tracts and well-wooded hills, alternating with fertile valleys watered mainly by the Aare and its tributaries.[21] The valleys alternate with hills, many of which are wooded. Slightly over one-third of the canton is wooded (518 square kilometers (200 sq mi)), while nearly half is used from farming (635.7 square kilometers (245.4 sq mi)). 33.5 square kilometers (12.9 sq mi) or about 2.4% of the canton is considered unproductive, mostly lakes (notably Lake Hallwil) and streams. With a population density of 450/km2 (1,200/sq mi), the canton has a relatively high amount of land used for human development, with 216.7 square kilometers (83.7 sq mi) or about 15% of the canton developed for housing or transportation.[22]

It contains the hot sulphur springs of Baden and Schinznach-Bad, while at Rheinfelden there are very extensive saline springs. Just below Brugg the Reuss and the Limmat join the Aar, while around Brugg are the ruined castle of Habsburg, the old convent of Königsfelden (with fine painted medieval glass) and the remains of the Roman settlement of Vindonissa (Windisch).

Fahr Monastery forms a small exclave of the canton, otherwise surrounded by the canton of Zürich, and since 2008 is part of the Aargau municipality of Würenlos.

Political subdivisions

[edit]Districts

[edit]

Aargau is divided into 11 districts:

- Aarau with capital Aarau

- Baden with capital Baden

- Bremgarten with capital Bremgarten

- Brugg with capital Brugg

- Kulm with capital Unterkulm

- Laufenburg with capital Laufenburg

- Lenzburg with capital Lenzburg

- Muri with capital Muri

- Rheinfelden with capital Rheinfelden

- Zofingen with capital Zofingen

- Zurzach with capital Zurzach

The most recent change in district boundaries occurred in 2010 when Hottwil transferred from Brugg to Laufenburg, following its merger with other municipalities, all of which were in Laufenburg.

Municipalities

[edit]There are (as of 2014) 213 municipalities in the canton of Aargau. As with most Swiss cantons there has been a trend since the early 2000s for municipalities to merge, though mergers in Aargau have so far been less radical than in other cantons.

Coat of arms

[edit]The blazon of the coat of arms is Per pale, dexter: sable, a fess wavy argent, charged with two cotises wavy azure; sinister: sky blue, three mullets of five argent.[23]

The flag and arms of the canton of Aargau date to 1803 and are an original design by Samuel Ringier-Seelmatter; the current official design, specifying the stars as five-pointed, dates to 1930.

Demographics

[edit]Aargau has a population (as of December 2020[update]) of 694,072.[2] As of 2010[update], 21.5% of the population are resident foreign nationals. Over the last 10 years (2000–2010) the population has changed at a rate of 11%. Migration accounted for 8.7%, while births and deaths accounted for 2.8%.[24] Most of the population (as of 2000[update]) speaks German (477,093 or 87.1%) as their first language, Italian is the second most common (17,847 or 3.3%) and Serbo-Croatian is the third (10,645 or 1.9%). There are 4,151 people who speak French and 618 people who speak Romansh.[25]

Of the population in the canton, 146,421 or about 26.7% were born in Aargau and lived there in 2000. There were 140,768 or 25.7% who were born in the same canton, while 136,865 or 25.0% were born somewhere else in Switzerland, and 107,396 or 19.6% were born outside of Switzerland.[25]

As of 2000[update], children and teenagers (0–19 years old) make up 24.3% of the population, while adults (20–64 years old) make up 62.3% and seniors (over 64 years old) make up 13.4%.[24]

As of 2000[update], there were 227,656 people who were single and never married in the canton. There were 264,939 married individuals, 27,603 widows or widowers and 27,295 individuals who are divorced.[25]

As of 2000[update], there were 224,128 private households in the canton, and an average of 2.4 persons per household.[24] There were 69,062 households that consist of only one person and 16,254 households with five or more people. As of 2009[update], the construction rate of new housing units was 6.5 new units per 1000 residents.[24] The vacancy rate for the canton, in 2010[update], was 1.54%.[24]

The majority of the population is centered on one of three areas: the Aare Valley, the side branches of the Aare Valley, or along the Rhine.[5]

Historic population

[edit]The historical population is given in the following chart:[26][27][28]

| Historic Population Data[26] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total Population | German Speaking | Italian Speaking | Protestant | Catholic | Christian Catholic | Jewish | Other | No religion given | Swiss | Non-Swiss |

| 1850 | 199,852 | 107,194 | 91,096 | 1,562 | 79 | 196,890 | 2,962 | ||||

| 1900 | 206,498 | 203,071 | 2,415 | 114,176 | 91,039 | 990 | 293 | 196,455 | 10,043 | ||

| 1950 | 300,782 | 291,101 | 5,335 | 171,296 | 122,172 | 5,096 | 496 | 1,722 | 290,049 | 10,733 | |

| 1990 | 507,508 | 435,103 | 24,758 | 218,379 | 224,836 | 3,676 | 405 | 29,736 | 30,476 | 420,616 | 86,892 |

| 1993[7] | 512,000 | ||||||||||

| 2000 | 547,493 | 477,093 | 17,847 | 203,949 | 219,800 | 3,418 | 342 | 20,816 | 57,573 | ||

Politics

[edit]In the 2011 federal election, the most popular party was the SVP which received 34.7% of the vote. The next three most popular parties were the SP/PS (18.0%), the FDP (11.5%) and the CVP (10.6%).[29]

The SVP received about the same percentage of the vote as they did in the 2007 Federal election (36.2% in 2007 vs 34.7% in 2011). The SPS retained about the same popularity (17.9% in 2007), the FDP retained about the same popularity (13.6% in 2007) and the CVP retained about the same popularity (13.5% in 2007).[30]

Federal election results

[edit]| Percentage of the total vote per party in the canton in the National Council Elections 1971-2023[31] | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Ideology | 1971 | 1975 | 1979 | 1983 | 1987 | 1991 | 1995 | 1999 | 2003 | 2007 | 2011 | 2015 | 2019 | 2023 | |

| SVP/UDC | Swiss nationalism | 12.5 | 12.8 | 13.9 | 14.1 | 15.7 | 17.9 | 19.8 | 31.8 | 34.6 | 36.2 | 34.7 | 38.0 | 31.5 | 35.5 | |

| SP/PS | Social democracy | 23.9 | 24.2 | 27.6 | 27.5 | 18.5 | 17.4 | 19.4 | 18.7 | 21.2 | 17.9 | 18.0 | 16.1 | 16.5 | 16.4 | |

| FDP.The Liberalsa | Classical liberalism | 15.9 | 17.7 | 20.5 | 20.2 | 20.3 | 16.4 | 15.8 | 17.2 | 15.3 | 13.6 | 11.5 | 15.1 | 13.6 | 13.1 | |

| The Centre | Christian democracy | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 12.0 | |

| GLP/PVL | Green liberalism | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 5.7 | 5.2 | 8.5 | 8.5 | |

| GPS/PES | Green politics | * | * | * | * | * | 6.8 | 5.3 | 4.4 | 5.1 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 9.8 | 7.1 | |

| EVP/PEV | Christian democracy | 3.8 | 4.6 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 5.2 | 4.2 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.6 | 4.5 | |

| EDU/UDF | Christian right | * | * | * | * | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | * | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| CVP/PDC/PPD/PCD | Christian democracy | 20.0 | 20.6 | 22.5 | 21.5 | 18.9 | 14.5 | 14.2 | 16.3 | 15.6 | 13.5 | 10.6 | 8.6 | 9.9 | * d | |

| BDP/PBD | Conservatism | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 6.1 | 5.1 | 3.1 | * d | |

| SD/DS | National conservatism | 3.4 | 3.5 | 1.6 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 2.7 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | * | * | * | |

| FPS/PSL | Right-wing populism | * | * | * | * | 5.3 | 13.2 | 11.3 | 1.4 | 0.2 | * | * | * | * | * | |

| FGA | Feminist | * | * | * | * | 6.9 | * c | 0.1 | * | 0.8 | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Ring of Independents | Social liberalism | 9.4 | 6.6 | 5.5 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 3.3 | 2.0 | * b | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Rep. | Right-wing populism | 5.8 | 6.5 | 2.1 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| POCH | Progressivism | * | 0.6 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| Other | 5.2 | 2.9 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 4.7 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 1.9 | ||

| Voter participation % | 62.5 | 50.7 | 45.6 | 44.9 | 43.1 | 42.3 | 42.1 | 42.0 | 42.3 | 47.9 | 48.5 | 48.3 | ||||

- ^a FDP before 2009, FDP.The Liberals after 2009

- ^b "*" indicates that the party was not on the ballot in this canton.

- ^c Part of the GPS

- ^d CVP and BDP merged to form The Centre party.

Cantonal politics

[edit]The Grand Council of the canton of Aargau is called Grosser Rat. It is the legislature of the canton, has 140 seats, with members elected every four years.

Religion

[edit]

From the 2000 census[update], 219,800 or 40.1% were Roman Catholic, while 189,606 or 34.6% belonged to the Swiss Reformed Church. Of the rest of the population, there were 11,523 members of an Orthodox church (or about 2.10% of the population), there were 3,418 individuals (or about 0.62% of the population) who belonged to the Christian Catholic Church, and there were 29,580 individuals (or about 5.40% of the population) who belonged to another Christian church. There were 342 individuals (or about 0.06% of the population) who were Jewish, and 30,072 (or about 5.49% of the population) who were Muslim. There were 1,463 individuals who were Buddhist, 2,089 individuals who were Hindu and 495 individuals who belonged to another church. 57,573 (or about 10.52% of the population) belonged to no church, are agnostic or atheist, and 15,875 individuals (or about 2.90% of the population) did not answer the question.[25]

Education

[edit]In Aargau about 212,069 or (38.7%) of the population have completed non-mandatory upper secondary education, and 70,896 or (12.9%) have completed additional higher education (either university or a Fachhochschule). Of the 70,896 who completed tertiary schooling, 63.6% were Swiss men, 20.9% were Swiss women, 10.4% were non-Swiss men and 5.2% were non-Swiss women.[25]

Economy

[edit]

As of 2010[update], Aargau had an unemployment rate of 3.6%. As of 2008[update], there were 11,436 people employed in the primary economic sector and about 3,927 businesses involved in this sector. 95,844 people were employed in the secondary sector and there were 6,055 businesses in this sector. 177,782 people were employed in the tertiary sector, with 21,530 businesses in this sector.[24]

In 2008[update] the total number of full-time equivalent jobs was 238,225. The number of jobs in the primary sector was 7,167, of which 6,731 were in agriculture, 418 were in forestry or lumber production and 18 were in fishing or fisheries. The number of jobs in the secondary sector was 90,274 of which 64,089 or (71.0%) were in manufacturing, 366 or (0.4%) were in mining and 21,705 (24.0%) were in construction. The number of jobs in the tertiary sector was 140,784. In the tertiary sector; 38,793 or 27.6% were in the sale or repair of motor vehicles, 13,624 or 9.7% were in the movement and storage of goods, 8,150 or 5.8% were in a hotel or restaurant, 5,164 or 3.7% were in the information industry, 5,946 or 4.2% were the insurance or financial industry, 14,831 or 10.5% were technical professionals or scientists, 10,951 or 7.8% were in education and 21,952 or 15.6% were in health care.[32]

Of the working population, 19.5% used public transportation to get to work, and 55.3% used a private car.[24] Public transportation – bus and train – is provided by Busbetrieb Aarau AG.

The farmland of the canton of Aargau is some of the most fertile in Switzerland. Dairy farming, cereal and fruit farming are among the canton's main economic activities.[7] The canton is also industrially developed, particularly in the fields of electrical engineering, precision instruments, iron, steel, cement and textiles.[7]

Three of Switzerland's five nuclear power plants are in the canton of Aargau (Beznau I + II and Leibstadt). Additionally, the many rivers supply enough water for numerous hydroelectric power plants throughout the canton. The canton of Aargau is often called "the energy canton".

A significant number of people commute into the financial center of the city of Zürich, which is just across the cantonal border. As such the per capita cantonal income (in 2005) is 49,209 CHF.[33]

Tourism is significant, particularly for the hot springs at Baden and Schinznach-Bad, the ancient castles, the landscape, and the many old museums in the canton.[21] Hillwalking is another tourist attraction but is of only limited significance.

See also

[edit]- Aargauer Zeitung

- FC Aarau

- Grand Prix of Aargau Canton, bicycle race

Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Arealstatistik Land Cover - Kantone und Grossregionen nach 6 Hauptbereichen accessed 27 October 2017

- ^ a b "Ständige und nichtständige Wohnbevölkerung nach institutionellen Gliederungen, Geburtsort und Staatsangehörigkeit". bfs.admin.ch (in German). Swiss Federal Statistical Office - STAT-TAB. 31 December 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Statistik, Bundesamt für (21 January 2021). "Bruttoinlandsprodukt (BIP) nach Grossregion und Kanton - 2008-2018 | Tabelle". Bundesamt für Statistik (in German). Retrieved 1 July 2023.

- ^ "The Aargau location - your advantage". Departement Volkswirtschaft und Inneres, ag.ch. Retrieved 30 January 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Van Valkenburg 1997, p. 3

- ^ a b Ogrizek & Rufenacht 1949, p. 4

- ^ a b c d e Cohen 1998, p. 1

- ^ Farbkarte 2002, p. 283

- ^ Peter Frey. "Die Habsburg. Bericht über die Ausgrabungen von 1994/95" in: Argovia, Jahresschrift der Historischen Gesellschaft des Kantons Aargau 109 (1997), p. 167.

- ^ a b c d Luck 1985, p. 98

- ^ Luck 1985, p. 88

- ^ a b c Sauerlände 2002

- ^ a b c Wohle 2006

- ^ Gasser & Keller 1932, p. 82

- ^ a b c d e Steigmeier 2002

- ^ Bridgwater & Aldrich 1968, p. 11

- ^ a b Ariel David (14 October 2018). "Oldest Jewish Community in Switzerland Is Disappearing, but Not Without a Fight". Haaretz.

- ^ a b c d e f Kayserling 1906, pp. 1–2

- ^ Steigmeier, Andreas (4 February 2008). "Judenäule" (in German). HDS. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ "Jüdischer Friedhof Endingen / Lengau (Kanton Aargau / CH)" (in German). alemannia-judaica.de. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ a b Hoiberg 2010, p. 4

- ^ Federal Department of Statistics 2006

- ^ Heimer 2000

- ^ a b c d e f g Swiss Federal Statistical Office 2013[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d e Federal Department of Statistics 2000

- ^ a b Steigmeier 2010

- ^ Federal Department of Statistics 2011

- ^ Federal Department of Statistics 2011a

- ^ Heer 2013

- ^ Federal Department of Statistics 2013

- ^ Nationalratswahlen: Stärke der Parteien nach Kantonen (Schweiz = 100%) (Report). Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ Federal Department of Statistics 2013a

- ^ Federal Department of Statistics 2013b [full citation needed]

References

[edit]- Bridgwater, W.; Aldrich, Beatrice, eds. (1968). "Aargau". The Columbia-Viking Desk Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0670230709.

- Cohen, Saul B., ed. (1998). "Aargau". The Columbia Gazetteer of the World. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11040-5.

- Farbkarte, S. (2002). Neuenschwander, Eva Meret; Schneider, Jürg (eds.). Schweiz mit Liechtenstein [Switzerland with Liechtenstein] (in German). Bielefeld, Germany: Reise Know-how Verlag. ISBN 3-8317-1064-3.

- Federal Department of Statistics (2013). "Nationalratswahlen 2007: Stärke der Parteien nach Kanton" [Election 2007: strength of the parties to Canton]. Archived from the original (Excel) on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- Federal Department of Statistics (2013a). "STAT-TAB: Die interaktive Statistikdatenbank: Datenwürfel für Thema 06.2 – Unternehmen" [STAT-TAB: The interactive statistical database: Data cube for about 06.2 – company]. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- Federal Department of Statistics (2013b). "Federal Department of Statistics". Archived from the original on 16 November 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.[full citation needed]

- Federal Department of Statistics (2011). "Sprachen, Religionen – Daten, Indikatoren Religionen" [Languages, religions – Data, indicators religions]. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- Federal Department of Statistics (2011a). "Sprachen, Religionen – Daten, Indikatoren Sprachen" [Languages, religions – Data, indicators languages]. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- Federal Department of Statistics (2006). "Arealstatistik – Kantonsdaten nach 15 Nutzungsarten" [Land Use Statistics – Canton data after 15 uses]. Archived from the original (Excel) on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- Federal Department of Statistics (2000). "STAT-TAB: Die interaktive Statistikdatenbank" [STAT-TAB: The interactive statistical database]. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- Gasser, Adolf; Keller, Ernst (1932). Die territoriale Entwicklung der schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft 1291–1797 [The territorial development of the Swiss Confederation, 1291–1797] (in German). Aarau: Sauerländer.

- Heer, Oliver (2013). "Eingereichte Listen bei den Nationalratswahlen 1971 – 2011, nach Parteien" [Submitted lists for the National Council elections 1971 – 2011, after parties]. Federal Office of Statistics. Archived from the original (Excel) on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- Heimer, Željko (2000). "Aargau canton (Switzerland)". Flags of the World.com. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Aargau". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kayserling, Moritz (1906). "Aargau". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kayserling, Moritz (1906). "Aargau". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.- Luck, James Murray (1985). A History of Switzerland: The First 100,000 years: Before the Beginnings to the days of the Present. Palo Alto, CA: Sposs Inc. ISBN 0-930664-06-X.

- Ogrizek, Doré; Rufenacht, J. G., eds. (1949). Switzerland. World in Color Series. New York, NY: Whittlesey House. ASIN B0027ESLB2.

- Sauerlände, Dominik (2002): Berner Aargau in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Steigmeier, Andreas (2010): Aargau in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Steigmeier, Andreas (2002): Baden (AG), County in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office (2013). "Swiss Statistics Web site". Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 26 January 2012.[full citation needed]

- Van Valkenburg, Samuel (1997). "Aargau". In Johnston, Bernard (ed.). Collier's Encyclopedia. Vol. I: A to Ameland (1st ed.). New York, NY: P.F. Collier.

- Wohle, Anton (2006): Freie Ämter in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

External links

[edit]- Official website

(in German)

(in German) - Aargau in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Official statistics (archived 15 November 2013)

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I (9th ed.). 1878. p. 3.

- "Aargau". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

- "Aargau". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I (11th ed.). 1911. p. 3.

- "Aargau". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

Aargau

View on GrokipediaHistory

Prehistoric and ancient periods

Human presence in the region of present-day Aargau dates to the Neolithic period, with archaeological evidence from lake shore settlements indicative of early agrarian communities exploiting fertile alluvial soils near water bodies. The Ägelmoos site yielded potsherds dated to 4400–4100 BC, marking one of the earliest known pile-dwelling occupations in the Swiss Plateau, characterized by stilt-built structures adapted to lacustrine environments.[9] Similarly, the Riesi-Seengen pile dwelling, part of UNESCO-recognized Alpine prehistoric settlements, reflects sustained Neolithic habitation patterns reliant on fishing, hunting, and rudimentary farming.[10] Bronze Age activity is attested by fewer but significant finds, including the Middle Bronze Age settlement at Gränichen-Lochgasse, where excavations from 2016–2017 uncovered approximately 10,000 m² of structures, tools, and ceramics, suggesting organized village life amid forested landscapes.[11] Transitional evidence between Neolithic and Bronze Age (ca. 2400–1800 BCE) remains sparse, pointing to possible climatic or cultural shifts that limited preserved artifacts. These sites underscore settlement driven by riverine fertility, particularly along the Aare, precursors to denser Roman-era exploitation. Under Roman administration, Aargau formed part of the province of Helvetia, established after Julius Caesar's conquest of the Helvetii Celts in 58 BC, with infrastructure focused on military control and trade routes. The legionary camp at Vindonissa (modern Windisch) was founded ca. 15–16 AD under Emperor Tiberius on a site overlying a Celtic oppidum, housing up to 6,000 troops from legions such as the XXI Rapax, initially garrisoned there until ca. 101 AD.[12][13] Accompanying the fortress were a civilian vicus, amphitheatre, aqueduct, and roads facilitating connectivity along the Aare River, evidencing Roman engineering to secure the Rhine frontier against Germanic incursions. Villas and farms dotted the landscape, integrating local Celtic populations into imperial economy via viticulture and grain production.[14] Following Roman withdrawal around 401 AD amid empire-wide pressures, Alemannic Germanic tribes migrated into the vacated Helvetian territories, including Aargau, by the mid-5th century, supplanting Romano-Celtic elements through settlement and assimilation.[15] This influx, part of broader Migration Period dynamics, introduced Alemannic dialects and pagan customs, laying foundations for enduring Germanic cultural dominance in the region prior to Frankish conquest in 496 AD. Archaeological transitions show continuity in rural land use but shifts toward decentralized tribal organization.Medieval Aargau and Habsburg rule

The House of Habsburg originated in the region of present-day Aargau, with their ancestral Habsburg Castle founded in the 11th century near the Aare River.[16] In the 13th century, Rudolf I of Habsburg significantly expanded family holdings by purchasing Lenzburg Castle in 1273, consolidating control over lands around fortresses such as Lenzburg and Aarburg.[17] These acquisitions formed the basis for Habsburg dominance in the area, which they administered through a system of bailiwicks (Ämter), including the Eigenamt, where local governance persisted amid feudal fragmentation.[18] Habsburg rule, however, encountered resistance from semi-autonomous entities that preserved local self-governance traditions. The Freie Ämter, territories nominally under Habsburg suzerainty, operated with independence in low justice and communal affairs, enabling peasant communities to counterbalance feudal lords and avoid over-centralization.[19] Similarly, imperial cities and counties like Baden maintained privileges as free imperial lands, fostering alliances with emerging Swiss cantonal interests against Habsburg expansionism.[20] These dynamics of fragmented authority culminated in the Swiss Confederacy's conquest of Aargau in 1415, exploiting Habsburg vulnerabilities during the Council of Constance, when Emperor Sigismund encouraged the cantons to seize Habsburg territories.[21] Cantons including Bern, Zurich, and Lucerne overran the region between April and May, ending direct Habsburg control and dividing Aargau into Bernese possessions and joint confederate administrations like the County of Baden.[22] This event underscored the limits of Habsburg centralization efforts, as local autonomies had already eroded feudal cohesion.[23]Reformation and early modern fragmentation

The Protestant Reformation, initiated by Huldrych Zwingli in Zurich from 1519, extended its influence into the fragmented territories of Aargau during the 1520s, challenging Catholic Habsburg legacies and local traditions. Zwingli's emphasis on biblical authority over ecclesiastical rituals resonated in areas adjacent to Zurich, prompting debates and conversions among clergy and laity. However, resistance persisted in rural districts, exemplified by the 1526 Disputation of Baden, where Catholic theologian Johann Eck defended orthodoxy against Zwinglian proponents, securing papal condemnation of reformist ideas and maintaining Catholic majorities in agrarian regions.[24] Bern's adoption of the Reformation in 1528, following internal disputations, extended Protestant governance to Unteraargau, which Bern had administered since conquering it from Habsburg control in 1415. This created sharp confessional boundaries: Protestant Bernese territories in the lower Aargau contrasted with Catholic strongholds in condominiums like the County of Baden, jointly ruled by eight Old Swiss Confederacy cantons of mixed faiths, including Protestant Zurich and Catholic Lucerne. Such divides exacerbated administrative fragmentation, as religious affiliations dictated alliances and policies, preventing unified reform or counter-reform across the region.[19] Semi-autonomous entities, including the Freie Ämter—Habsburg-era lands with independent low justice—and the County of Baden endured as common lordships into the late 18th century, their decentralized structures reinforced by confessional tensions. The Freie Ämter, initially under Catholic cantonal oversight, saw Protestant Bern supplant Catholic administrators in 1712 after the Second Villmergen War, a conflict rooted in religious disputes that highlighted the fragility of shared rule. Peasant discontent with taxation and tithes manifested in revolts, such as the 1653 uprising in Bernese domains triggered by currency devaluation and fiscal burdens, which spilled into Aargau territories and exposed the inefficiencies of overlordship, nurturing resistance to centralized exactions and proto-federalist autonomy.[19]Napoleonic era and canton formation

The French invasion of Switzerland in early 1798, part of the Revolutionary Wars, led to the rapid occupation of the region that would become Aargau. French forces entered the area on March 10, 1798, and by April 18, they had secured control, dissolving the Old Swiss Confederacy's structures. The Bernese-controlled portions of the territory were reorganized into the Canton of Aargau within the newly proclaimed Helvetic Republic on April 12, 1798, while the remaining areas, including the County of Baden, formed the separate Canton of Baden. The Fricktal region, previously under Habsburg influence, was annexed to France in 1799 before being added as a third provisional canton in 1802.[6][25] The Helvetic Republic imposed a centralized, unitary state modeled on French revolutionary principles, abolishing cantonal autonomy and traditional local governance, which provoked widespread resistance among Swiss populations accustomed to decentralized confederation. This top-down centralization failed to account for Switzerland's cultural and linguistic diversity, leading to economic stagnation, administrative inefficiencies, and armed uprisings, culminating in the Stecklikrieg civil war of September 1802 that effectively collapsed the republic. The experiment demonstrated the impracticality of enforcing uniform Jacobin-style reforms on a federation rooted in local sovereignty, as cantons and rural communities rejected the erosion of their self-rule.[26][25] Napoleon Bonaparte, seeking to stabilize the region amid his campaigns, issued the Act of Mediation on February 19, 1803, which reestablished a loose confederation of 19 cantons with restored but limited sovereignty under French protection. For Aargau, the Act merged the short-lived cantons of Aargau, Baden, and Fricktal into a single entity on January 12, 1803, combining former Bernese bailiwicks, Habsburg territories around Baden, and the independent Freie Ämter. This new Canton Aargau was granted full membership in the confederation, averting further radical centralization by prioritizing cantonal self-governance within the federal framework.[27][25] The ensuing cantonal constitution, adopted shortly after, enshrined Aargau's sovereignty in internal affairs, including legislative and executive powers devolved to local bodies, while aligning with the Mediation Act's emphasis on confederate unity without subordinating cantons to a dominant central authority. This structure preserved the aversion to the Helvetic era's failed experiments, fostering stability by balancing national coordination with regional autonomy until the post-Napoleonic restoration.[27]Industrialization and 19th-century development

The liberal constitution adopted by the Canton of Aargau in 1841 established a framework of representative government based on population proportionality, abolishing monastic privileges and reducing state intervention in economic affairs, which facilitated private initiative and free trade orientations distinct from more regulated neighboring cantons.[28] This shift, driven by radical-liberal reforms under figures like Augustin Keller, dismantled feudal remnants and promoted market-driven agriculture and manufacturing, enabling entrepreneurs to capitalize on emerging opportunities without the encumbrances of guild restrictions or conservative agrarian policies prevalent elsewhere in the Swiss Confederation.[29] Railway infrastructure catalyzed industrial expansion, beginning with the opening of the Zürich-Baden line on August 7, 1847, by the Schweizerische Nordostbahn, which linked Aargau's key towns to Zurich and reduced freight costs by over 50% compared to horse-drawn transport.[30] Subsequent lines, such as extensions toward Olten by the 1850s and further integrations by 1860, created a network spanning 200 kilometers within the canton by 1870, directly boosting manufacturing by enabling efficient raw material imports and product exports, with private companies like the Nordostbahn bearing the investment risks and reaping efficiency gains.[31] In parallel, textile production transitioned from cottage-based proto-industry to mechanized mills, particularly in Wettingen where cotton spinning and weaving employed thousands by mid-century, while Aarau's metal sector advanced from traditional ironworking to machine-tool fabrication, leveraging local ore and hydropower for output growth exceeding 300% in metal goods between 1840 and 1870.[32][33] Agricultural adaptations complemented this takeoff, as cheap grain imports post-1848 prompted a reorientation from subsistence cereals to high-value dairy and fodder crops, with Aargau's flatlands seeing dairy cow numbers rise from approximately 50,000 in 1850 to over 100,000 by 1900 through private cooperatives introducing selective breeding and silo storage.[34] Fruit cultivation expanded in the Fricktal and along the Aare, yielding specialized orchards for apples and cherries that tripled export volumes by the 1870s, driven by individual farmers' responses to rail-enabled market access rather than centralized mandates, thereby enhancing overall canton prosperity through diversified, enterprise-led specialization.[35] This interplay of liberal policies, transport innovations, and adaptive farming—rooted in decentralized decision-making—underpinned Aargau's population surge of 25% from 1840 to 1860, outpacing agrarian cantons and evidencing the causal role of private incentives in sustaining economic momentum.[31]20th-century challenges and nuclear era

Switzerland's policy of armed neutrality preserved the Canton of Aargau from direct involvement in World War I and World War II, avoiding invasion despite proximity to conflict zones.[36] Economic strains included inflation, food and raw material shortages, and export disruptions, which affected industrial output reliant on international trade.[37] These challenges prompted rationing and domestic production boosts, yet the canton's independence remained intact through fortified defenses and diplomatic adherence to neutrality principles.[38] Post-World War II, Aargau experienced rapid industrialization from the 1950s to 1970s, driven by its strategic location, water resources, and infrastructure.[39] Key sectors included chemicals and pharmaceuticals, with expansions by firms such as Siegfried AG in Zofingen and Dottikon Exclusive Synthesis, transitioning from explosives to fine chemicals and active pharmaceutical ingredients.[40][41] Companies like Roche established production sites in Kaiseraugst, leveraging the Fricktal region's facilities for chemical processing and drug manufacturing.[42] This growth contributed to employment and export diversification, mitigating vulnerabilities from wartime dependencies on imported energy and materials.[4] The nuclear era marked a pragmatic shift toward energy security, exemplified by the Beznau Nuclear Power Plant in Döttingen, where Unit 1 commenced commercial operation in December 1969 and Unit 2 in 1972.[43] Built amid rising fossil fuel imports, these pressurized water reactors provided baseload electricity, generating up to 365 MWe each and reducing reliance on volatile oil supplies exacerbated by the 1973 and 1979 crises.[44] Empirically, nuclear power's low operational emissions—far below those of coal or natural gas—and high capacity factors exceeding 90% offered cost-effective, dispatchable energy superior to intermittent renewables for grid stability.[44] By the late 20th century, Beznau contributed significantly to Switzerland's low-carbon electricity mix, approximately 40% nuclear-derived, enhancing resilience without the supply risks of hydrocarbons.[45]Post-2000 developments and economic resilience

In the early 2000s, Switzerland's direct democracy mechanisms enabled rigorous scrutiny of European Union integration efforts through federal referendums on bilateral accords, preserving cantonal autonomy and low-regulation policies. The 2005 approval of Schengen and Dublin agreements via referendum granted Aargau, a border canton adjacent to Germany, enhanced cross-border mobility and trade access without subjecting its economy to full EU regulatory frameworks.[46] This approach allowed Aargau to maintain deregulated industrial sectors, such as manufacturing and logistics, benefiting from bilateral market openings while voters rejected deeper alignment that could impose harmonized standards.[47] During the 2008 global financial crisis, Aargau's economic resilience stemmed from Switzerland's overarching fiscal conservatism, characterized by low public debt and prudent budgeting, which mitigated downturns without resorting to expansive bailouts beyond the federal intervention for UBS. The canton's diversified economic base, including precision engineering and chemicals, experienced contained impacts, supported by strong institutional frameworks that prioritized expenditure control and tax revenue stability.[48] Direct democratic oversight reinforced this conservatism, as cantonal referendums historically curbed deficit spending, enabling Aargau to sustain AAA credit ratings and avoid the debt surges seen in more interventionist economies.[48] The COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted Aargau's policy of prioritizing economic openness, with Switzerland's federal short-time work schemes preventing sharp unemployment rises and maintaining supply chains in the canton. Aargau's financial performance remained resilient amid expenditure pressures, bolstered by higher tax revenues from recovering industries and disciplined fiscal measures approved through local democratic processes.[48] By 2024, these low-regulation policies, sustained via direct democracy's rejection of overreach, positioned Aargau as the top-ranked canton in the Avenir Suisse Freedom Index, achieving superior scores in both economic liberty—through minimal barriers to business—and social freedoms, underscoring the causal link between deregulation and sustained prosperity.[49]Geography

Physical features and terrain

The terrain of Aargau encompasses the northern fringes of the Swiss Plateau in its central and southern districts, characterized by gently undulating plains at elevations between approximately 300 and 500 meters, with the city of Aarau situated at 377 meters above sea level.[50] These plateau areas feature molasse sediments from the Tertiary period overlaid by Quaternary deposits, forming a substrate suitable for intensive arable farming and urban-industrial development.[51] In the north, the landscape ascends into the Jura Mountains, where tectonic folding of Jurassic limestone creates parallel ridges, plateaus, and narrow valleys, with elevations rising to over 900 meters.[52] This folded Jura terrain, part of the larger subalpine chain, includes karst features such as dry valleys and rocky outcrops, limiting large-scale agriculture but enabling localized pasture and forestry activities.[51] Glacial deposits from Pleistocene Alpine ice advances mantle much of the plateau and Jura foothills, including till and gravel in areas like Möhlin, which have influenced local topography through moraine ridges and eskers while providing raw materials for aggregate extraction supporting construction and infrastructure.[53] These features underpin the canton's economic adaptation, with the plateau's even relief favoring transport networks and manufacturing hubs, whereas the Jura's steeper slopes constrain settlement to valleys and passes. Nature reserves in the Jura preserve pockets of calcareous grasslands and beech forests amid predominantly anthropogenically shaped landscapes optimized for productive land use.[53]Hydrology and rivers

The Aare River constitutes the primary hydrological feature of Aargau, forming its lower course as it flows northward across the Swiss Plateau from the cantonal border with Solothurn toward the Rhine. Measuring 288 kilometers in total length from its source in the Bernese Alps, the Aare's segment through Aargau supports extensive alluvial deposits that underpin agricultural productivity, with discharge augmented by precipitation and upstream inflows. The Reuss River, a 164-kilometer tributary originating in the Gotthard massif, converges with the Aare near Brugg and Windisch at an elevation of roughly 350 meters, creating a significant confluence that historically amplified navigability and sediment deposition in the region. Other notable tributaries entering the Aare within Aargau bounds include the Wigger, which joins near Aarburg after draining central plateaus.[54][55] These river systems exerted causal influence on early human settlement by providing reliable water sources, fertile floodplains for cultivation, and transport corridors that linked inland areas to broader trade networks. Confluences like that of the Aare and Reuss at Windisch hosted prehistoric Celtic habitations and the Roman legionary camp of Vindonissa, established around 15 BC for its strategic oversight of river traffic and natural defenses afforded by the waterways. Settlements such as Aarwangen capitalized on the Aare as a merchandise route until the late 18th century, when overland infrastructure supplanted fluvial paths, fostering clustered development along banks for milling and fishing.[12][56] The Aare's consistent gradient and flow volume enabled early exploitation of hydroelectric potential, transitioning from water mills to modern installations, with the inaugural power station at Wynau operational by 1896 to harness the river's energy for regional electrification. Flood vulnerabilities prompted infrastructural responses, including 19th-century river corrections that straightened channels and reduced meanders to curb inundation risks, as evidenced by the 1748 deluge that obliterated Magden through cloudburst-induced overflows; these interventions have since lowered peak flood probabilities in the Aare valley by modifying hydraulic regimes and enhancing containment.[57][58][59]Climate and environmental conditions

Aargau exhibits a temperate oceanic climate classified under Köppen Cfb, characterized by mild temperatures, consistent precipitation, and moderate seasonal variations conducive to agriculture and settlement.[60] Annual mean temperatures average approximately 9.5°C, with July highs reaching 18.7°C and January lows around 0.5°C, reflecting mild winters rarely dipping below freezing for extended periods.[61] This stability supports diverse land uses, including viticulture in sheltered valleys where microclimates—shaped by topography and proximity to the Aare River and Lake Hallwil—provide warmer, frost-protected conditions ideal for grape cultivation, distinguishing Aargau's wine production in northern Switzerland.[62] Precipitation averages 1,200–1,300 mm annually, distributed fairly evenly with peaks in summer months like June (around 100 mm), fostering reliable soil moisture without excessive flooding risks in most areas.[61] [63] Empirical records indicate no long-term trends toward extremes that would undermine productivity; instead, the region's consistent humidity and moderate evaporation rates enhance crop yields, countering narratives of inherent climatic instability.[64] Environmental conditions remain favorable, with air quality metrics demonstrating low pollutant levels despite industrial presence near cities like Baden. PM2.5 concentrations typically fall below 10 µg/m³ annually, yielding Air Quality Index (AQI) readings in the "good" range (under 50) for over 90% of days, as monitored by real-time stations.[65] This data refutes unsubstantiated claims of widespread degradation, attributing clean metrics to natural ventilation from Jura foothills and prevailing westerlies, which disperse particulates efficiently.[66]Administrative divisions

Districts and their functions

The Canton of Aargau is subdivided into 11 districts (Bezirke): Aarau, Baden, Bremgarten, Brugg, Kulm, Laufenburg, Lenzburg, Muri, Rheinfelden, Zofingen, and Zurzach. These districts act as intermediate administrative layers, primarily responsible for coordinating cantonal policies with municipal implementation and managing regional judicial affairs through district courts that serve as courts of first instance for most civil and criminal cases.[67] [68] District administrations facilitate inter-municipal cooperation, enabling shared services in areas such as IT systems, procurement, and regional planning to achieve operational efficiencies and cost reductions, particularly emphasized in structural adjustments around 2010. This coordination supports fiscal discipline at the municipal level, where primary taxing authority resides, while districts allocate cantonal resources for cross-jurisdictional projects without independent fiscal powers. For instance, the Brugg district in the industrialized northern region prioritizes economic coordination for manufacturing and energy infrastructure, whereas the Lenzburg district emphasizes agricultural support and land management in rural areas.[69][70]| District | Key Regional Focus |

|---|---|

| Brugg | Industrial development and energy sector coordination[71] |

| Lenzburg | Agricultural and rural planning[71] |

| Baden | Urban administrative and transport hub functions[67] |