Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

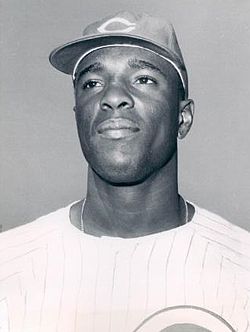

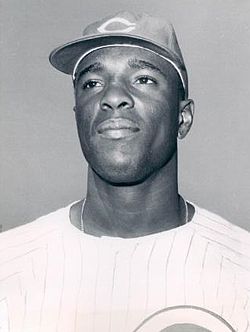

Alex Johnson

View on Wikipedia

Alex Johnson (December 7, 1942 – February 28, 2015) was an American professional baseball outfielder, who played in Major League Baseball (MLB), from 1964 to 1976, for the Philadelphia Phillies, St. Louis Cardinals, Cincinnati Reds, California Angels, Cleveland Indians, Texas Rangers, New York Yankees, and Detroit Tigers. He was the National League Comeback Player of the Year in 1968 and an American League All-Star and batting champion in 1970. His brother, Ron, was an NFL running back, most notably for the New York Giants.

Key Information

Early years

[edit]Johnson was born in Helena, Arkansas, and grew up in Detroit, Michigan with his two brothers and sisters. One brother Ron Johnson, was an NFL running back from 1969 to 1976.[1] Alex played sandlot ball with Bill Freehan, Willie Horton, and Dennis Ribant.[2]

Johnson attended Northwestern High School, where he excelled as an offensive lineman for the school's football team. He received a scholarship offer to attend Michigan State University to play football for the Michigan State Spartans, but opted to sign with the Philadelphia Phillies instead.[3]

Philadelphia Phillies

[edit]Johnson worked his way up the ranks quickly in the Phillies' farm system, batting .322 with 40 home runs and 187 runs batted in across two seasons to earn a spot on the Phillies' bench for the start of the 1964 season. However, he was optioned back to the Arkansas Travelers of the Pacific Coast League without having logged a major league at-bat in order to make room on the major league roster for relief pitcher Ed Roebuck, who was acquired from the Washington Senators shortly after the season started.[4]

Johnson soon earned a call back up to the majors as he batted .316 with 21 home runs and 71 RBIs in just over half a season with Arkansas. In his Major League Baseball debut, Johnson went 3-for-4 with a walk, two RBIs and a run scored.[5] He remained hot for his first month in the majors, batting .400 with one home run and nine RBIs through August. He eventually settled into a lefty-righty platoon with Wes Covington in left field, which he would do through the 1965 season. That October, the Phillies traded Johnson, Pat Corrales and Art Mahaffey to the St. Louis Cardinals for Bill White, Dick Groat and Bob Uecker.[6]

St. Louis Cardinals

[edit]To make room for Johnson in left field, St. Louis shifted Hall of Famer Lou Brock to right field. Along with Curt Flood in center, the Cardinals boasted one of the top young outfields in the National League heading into the 1966 season.[7] However, Johnson batted just .186 with two home runs and six RBIs through May 17 when he was sent down to the Tulsa Oilers of the Triple-A Pacific Coast League (PCL). That year, he was named the "Most Dangerous Hitter" in the PCL.[8]

Johnson returned to the Cardinals in 1967, batting .223 with one home run and twelve RBIs mostly as a pinch hitter and back up for Roger Maris in right field. The Cardinals defeated the Boston Red Sox in the World Series that year, though Johnson did not appear in the post-season. Just before spring training 1968, he was traded to the Cincinnati Reds for Dick Simpson.[9]

Cincinnati Reds

[edit]Pete Rose, the left fielder in Cincinnati in 1967, was shifted to right field for 1968. Mack Jones, a left-handed hitter acquired from the Atlanta Braves shortly before Johnson, was the early favorite to inherit the left field job.[10] While Johnson was labelled as "moody" and "uncoachable" during his days with the Phillies and Cardinals, he impressed Reds manager Dave Bristol that spring and was given the starting job in left field even though a lefthanded bat would have been more suitable for the Reds' line-up.[11]

By the time Johnson joined the Reds, he had a reputation as a notoriously slow starter. After batting .259 with four RBIs through April, Johnson got hot in May, batting .366 to move into the National League batting race. He finished the season at .312, fourth in the league behind Rose and two of the Alou brothers (Matty and Felipe), to be named the Sporting News' National League Comeback Player of the Year.[12]

Though his potential to hit for power was recognized throughout his early career, he entered the 1969 season having hit just 17 career home runs. He matched that total in 1969, while also driving in a career high 88 runs and scoring a career high 86 runs. He also finished sixth in the N.L. with a .315 batting average.[2]

Despite his hitting prowess, Johnson was a defensive liability as he led National League outfielders in errors both seasons in Cincinnati. In need of pitching, and with outfield prospect Bernie Carbo ready to jump to the majors, the Reds dealt Johnson and utility infielder Chico Ruiz to the California Angels for Pedro Borbón, Jim McGlothlin, and Vern Geishert.[13]

California Angels

[edit]Johnson hit the ground running in California, leading the league with a .366 batting average through May. He cooled off as the 1970 season progressed, but still went into the All-star break at .328 to earn selection to the A.L. squad.[14] He remained in the batting title race throughout the season, and went into the final game of the season with batting average which was .002 behind Boston's Carl Yastrzemski. In the last game of the season against the White Sox, Johnson went two-for-three to win the A.L. batting title by 0.0004 over Yastrzemski. He was removed from the game after his third at-bat, to ensure the title.[15]

Johnson became the subject of some controversy toward the end of his first season in California when he was fined by Angels manager Lefty Phillips for not running out a grounder. This continued into the following spring, when Phillips fined Johnson $100 for loafing in an exhibition game. The following day, Phillips removed Johnson from a second exhibition after he failed to run out a first-inning grounder.[16]

Things deteriorated during the 1971 regular season as Johnson was benched three times in May for indifferent play. On June 4, he was pulled in the first inning of a 10–1 loss to the Red Sox when he failed to run all the way to first base on a routine ground ball.[17] After being replaced by Tony González in left field, Johnson intimated that some of his battles with teammates and management were racially motivated.[18]

Hell yes, I'm bitter. I've been bitter ever since I learned I was black. The society into which I was born and in which I grew up and in which I play ball today is anti-black. My attitude is nothing more than a reaction of their attitude.

Following a June 13 loss to the Washington Senators, Johnson claimed that Chico Ruiz, who had been a close friend and was the godfather of Johnson's adopted daughter, pointed a gun at him while the two were in the clubhouse. Ruiz denied the claim.[19]

Johnson, limited as a fielder, stopped taking outfield practice before games. In June, after a potential trade deadline deal with the Milwaukee Brewers for Tommy Harper fell through, Johnson told reporters that he needed to get out of California, and that "playing in hell" would be an improvement.[20] Johnson was benched after he loafed on two balls hit to him in left field against Milwaukee, which resulted in a five-run fourth inning for the Brewers, and failed to run out a ground ball in his final at-bat in the ninth inning.[21] Phillips put it simply, "If you had seen him play lately, you'd know why he isn't in the line-up."[22]

By the end of June, Johnson had been benched five times and fined 29 times.[23] On June 26, Angels GM Dick Walsh suspended him without pay indefinitely for "not using his best efforts."[24]

Grievance and arbitration

[edit]Marvin Miller, executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association, immediately filed a grievance against the Angels on Johnson's behalf claiming that Walsh failed to properly outline the basis for the suspension in specific terms. His case, however, was weakened when Johnson defended his actions rather than deny the claims made against him by his ballclub. He admitted to not being in the spirit to play properly as the whole team was indifferent toward playing together.[25] Miller eventually ended up filing a grievance on Johnson's behalf suggesting that Johnson was emotionally disabled.[2]

Regardless of the grievance, Phillips remained defiant that Johnson would not be returning to his ballclub[26] (Phillips' stance was perhaps, in part, due to the fact that his fourth place team was suddenly playing better – 17–11 in the month of July.) When a meeting between Miller and the Owners' Players' Relations committee on July 21 failed to resolve the grievance, it went to an independent arbitrator.[27]

After a 30-day suspension, the longest the Angels could give, Commissioner of Baseball Bowie Kuhn placed Johnson on the restricted list, allowing the Angels to continue the suspension.[28] On August 10, Phillips, the Angels' coaches and six players (including team captain Jim Fregosi) met with Kuhn's labor advisor John Gaherin,[29] who was part of the three-man arbitration panel attempting to resolve the case along with Miller and professional Arbitrator Lewis Gill of the National Labor Relations Board. On August 31, the panel indefinitely postponed a decision on Johnson's appeal, and indicated that they were unlikely to come to an agreement before the end of the regular season.[30]

The Angels' case against Johnson hit a snag on September 7, when the Chicago Sun-Times reported that Walsh had lied about the gun incident with Ruiz, and ordered that the weapon be concealed.[31] Based on the findings of two psychiatrists, Gill found in favor of Johnson, determining that an emotional disturbance was no worse than a physical ailment, and that the Angels should not have suspended him, but rather should have placed Johnson on the disabled list. Johnson was awarded $29,970 in back pay (as players on the disabled list still receive full pay); however, Gill upheld the $3,750 in fines he received from the team.[32]

Cleveland Indians

[edit]After the season, the Angels cleaned house. Phillips and Walsh were both fired,[33] Ruiz was released, and Johnson was traded to the Cleveland Indians with Jerry Moses for Vada Pinson, Alan Foster, and Frank Baker.[34]

While more "emotional disturbance" followed Johnson to his new club when Ruiz was killed in an auto accident on February 9, 1972 (Johnson attended the funeral),[35] Johnson got off to a fast start for the Indians, as his batting average reached .328 on May 6. But a 6-for-66 slump brought his average down to .208 by June. Johnson appeared to be rebounding when he learned that Phillips, who had been rehired by the Angels as a scout, had had a fatal asthma attack on June 12.[36] He then went into a 5-for-37 slump that dropped his season average to .219.

Johnson's hitting problems were blamed on a heel injury, which limited him to pinch hitting during the first half of August.[37] He resumed his role of everyday left fielder on August 19, and batted .351 over the rest of the season.

Texas Rangers

[edit]

Johnson held out for a new contract with the Indians the following spring. Unable to reach an agreement, they traded him to the Texas Rangers for pitchers Rich Hinton and Vince Colbert. Rangers manager Whitey Herzog made it clear upon his team's acquisition of Johnson that he would release Johnson immediately if he turned out to be a discipline problem with his club.[38] However, with the American League's institution of the designated hitter rule in 1973, Johnson was able to provide strong offensive production for the Rangers without hindering his team defensively, and soon won over his new manager.[39] He appeared in 116 games at DH while spelling an occasional day off for Rico Carty in left in an additional forty games, and batted .287 with eight home runs and 68 RBIs. His 179 hits were the fifth most in the AL, and he held the Senators/Rangers franchise record in that category until 1979.[2]

Johnson became an everyday outfielder again when Billy Martin took over as Rangers manager toward the end of the 1973 season. At first, Johnson and Martin got along,[40] but by the time the Rangers sold Johnson's contract to the New York Yankees on September 9, 1974, Martin had also gotten fed up with him.[41]

New York Yankees

[edit]Johnson joined a Yankees club that was in first place by one game over the Baltimore Orioles in the American League East. In his first game as a Yankee, he hit an extra innings home run to defeat the Boston Red Sox.[42] It was, however, his only highlight with the Yankees as he batted just .214 in ten games with his new club, and the Orioles won the division by two games.

He started the 1975 season as the Yankees' regular DH, but a knee injury limited his role.[43] After Billy Martin was named Yankees manager on August 2, Johnson logged just nine more at-bats before he was released on September 2.

Detroit Tigers

[edit]Johnson signed with his hometown Detroit Tigers for the 1976 season,[44] and enjoyed something of a resurgent year as he batted .268 with six home runs and 45 RBIs as his team's everyday left fielder. Regardless, he was released at the end of the season.[45] He played briefly with the Mexican League's Diablos Rojos del México before retiring.[46]

Post-retirement

[edit]After Johnson retired, he returned to Detroit and in 1985, after his father's death, took over Johnson Trucking Service,[47] which was founded by his father, Arthur Johnson, in the 1940s.[8] The company rents dump trucks to construction companies.[48] In 1998, he told Sports Illustrated "Do I enjoy my life?" Johnson asks rhetorically. "I enjoy not being on an airplane all the time. I enjoy not having to face everything I did. I just want to help people with their vehicles. It's a nice, normal life — the thing I've always wanted."[49]

Personal life

[edit]Johnson married Julia Augusta in 1963, and they adopted daughter Jenifer in 1969 and had son Alex Jr. in 1972. Alex and Julia divorced after his baseball career ended.[50]

Johnson died on February 28, 2015, from complications of prostate cancer.[51]

Career statistics

[edit]| Games | PA | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BB | BA | OBP | SLG | FLD% |

| 1322 | 4948 | 4623 | 550 | 1331 | 180 | 33 | 78 | 525 | 113 | 244 | .288 | .326 | .392 | .953 |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hertzel, Bob (March 7, 1982). "Brother! Does Tribe have brother acts". The Cleveland Press. p. 43 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Armour, Mark. "Alex Johnson". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Dow, Bill (September 28, 2011). "Alex Johnson: The Detroit Tigers' Forgotten Batting Champion". Detroit Athletic Co. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Senators Sell Ed Roebuck to Phillies". Pittsburgh Press. April 21, 1964. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "St. Louis Cardinals 10, Philadelphia Phillies 9". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "White, Groat Dealt". St. Petersburg Times. October 28, 1965. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Cards Place Accent On Speed, Youth". Rochester Sentinel. March 23, 1966. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ a b Foster, Chris (June 24, 1990). "Alex Johnson's Bitterness Toward Baseball Still Evident 19 Years After the Angels Suspended Their Only Batting Champion for Lacking Effort". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Alex Johnson (#104)". 1966 Topps Baseball. June 2, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ O'Hara, Dave (March 12, 1968). "Yastrzemski Can Expect Rough Treatment From His Rivals". Kentucky New Era. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Friedman, A.J. (April 7, 1968). "Redlegs' Watchword: Stay In One Piece". Toledo Blade. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Comeback Player of the Year Award by The Sporting News". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Reds Trade Johnson, Ruiz To Angels". The Bryan Times. November 26, 1969. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "1970 Major League Baseball All-Star Game". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "California Angels 5, Chicago White Sox 4". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Phillips Benches Alex Johnson". The Rock Hill Herald. March 22, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ Eldridge, Larry (June 5, 1971). "Alex Johnson Benched by California Skipper". Waycross Journal-Herald. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Racial Issue Flares With Johnson". Gadsden Times. June 13, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Fimrite, Ron (July 5, 1971). "For Failure To Give His Best..." Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Must Leave Angels, Alex Says; Would Rather Play in Hell". The Miami News. June 24, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "Milwaukee Brewers 6, California Angels 0". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "10-Run Seventh Leads Cubs Over Cards, 21–0". Rochester Sentinel. June 26, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Armour, Mark L.; Levitt, Daniel R. "Chapter 11: Plans Gone Awry: The 1971 Angels". Paths to Glory: How Great Baseball Teams Got That Way. Potomac Books, Inc. pp. 217–231.

- ^ "Alex Johnson Had To Go, Claims California Angel". Lewiston Morning Tribune. June 28, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "'I Had Justifiable Reasons...'". The Day. July 1, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Alex Not Welcome, Lefty Phillips Says". The Miami News. July 7, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "Angel in Limbo". The Miami News. July 22, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "Deep Water For Johnson". St. Petersburg Times. July 28, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Angels, Staff, Pilot Parley on Johnson". Milwaukee Sentinel. August 11, 1971. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Panel Delays Verdict in Alex Johnson Case". The Morning Record. September 1, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Say Exec Lied in Johnson Case". The Milwaukee Sentinel. September 8, 1971. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "'Emotional Disturbance No Worse Than Physical – Pay Alex Johnson'". Lewiston Morning Tribune. September 29, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Angels Angling". The Spokesman Review. October 22, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Alex Johnson Says He Can't Wait to Play Baseball for the Cleveland Indians". The Miami News. October 6, 1971. Retrieved September 25, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "Accident Kills Royals' Ruiz". Palm Beach Post. February 10, 1972. Retrieved September 25, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "Lefty Phillips is Dead". St. Petersburg Independent. June 13, 1972. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Madden, Bill (August 6, 1972). "Alex Feeling Like a Heel While Indians Get On Feet?". Boca Raton News. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Cleveland Trades Holdout Alex Johnson". Sarasota Herald Tribune. March 10, 1973. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Herzog: Johnson is Texas' Best Hustler". Observer-Reporter. May 12, 1973. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Taylor, Jim (June 7, 1974). "Mood Right for Johnson". Toledo Blade. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Anderson, Dave (September 12, 1974). "Alex Joins the Yanks". The Day. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "New York Yankees 2, Boston Red Sox 1". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Injuries Plaguing Yanks, Phils". Palm Beach Post. June 19, 1975. Retrieved September 25, 2012.[dead link]

- ^ "Tigers Have New Look After Winter Shakeup". Gadsden Times. April 6, 1976. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ "Tigers Release Johnson, Garcia". Lakeland Ledger. December 17, 1976. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Popelka, Greg (May 11, 2011). "Blast From The Past: Alex Johnson". TheClevelandFan.com. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Pearlman, Jeff (March 9, 1998). "Alex Johnson, Angels Outfielder". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- ^ Foster, Chris (June 24, 1990). "Alex : Johnson's Bitterness Toward Baseball Still Evident 19 Years After the Angels Suspended Their Only Batting Champion for Lacking Effort". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Alex Johnson, Angels Outfielder". CNN. March 9, 1998. Archived from the original on July 11, 2013.

- ^ "Alex Johnson – Society for American Baseball Research".

- ^ Dittmeier, Bobbie (March 3, 2015). "Johnson, 1970 AL batting champion, dies". MLB.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2015. Retrieved March 3, 2015.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from MLB · ESPN · Baseball Reference · Fangraphs · Baseball Reference (Minors) · Retrosheet · Baseball Almanac

- Alex Johnson at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- Alex Johnson at Baseball Almanac

Alex Johnson

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Upbringing and Family Background

Alexander Johnson was born on December 7, 1942, in Helena, Arkansas, to Arthur Johnson Sr. and Willie Mae Johnson.[4][2] The family moved to Detroit, Michigan, when Johnson was a small boy, where he spent the remainder of his childhood.[2][5] Johnson grew up in Detroit alongside his parents, two brothers, and two sisters. His father worked initially in an automobile manufacturing plant before establishing a truck repair and leasing business that serviced the city's public schools.[2] One brother, Ron Johnson, achieved prominence as an All-American college football halfback and later as an All-Pro running back for the New York Giants in the NFL.[2] The Johnson family's relocation to Detroit immersed young Alex in an urban environment conducive to sandlot sports, where he played baseball and football with neighborhood peers who included future major leaguers Willie Horton and Bill Freehan.[2] This setting fostered his early athletic development amid a working-class household shaped by his father's entrepreneurial shift from factory labor to business ownership.[2][4]Entry into Baseball

Johnson developed an early interest in baseball while growing up in Detroit, Michigan, after his family relocated from Helena, Arkansas. At Northwestern High School, he starred as an outfielder on the baseball team and also played football, sharing the field with future Detroit Tigers standout Willie Horton. Despite earning football scholarship offers from Big Ten Conference universities, Johnson opted to focus on baseball, reasoning that he possessed superior talent and prospects in the sport compared to gridiron competition.[2] On July 11, 1961, immediately following his high school graduation, Johnson signed as an amateur free agent with the Philadelphia Phillies organization, forgoing college opportunities to begin his professional career. This decision aligned with the pre-draft era practices, where teams scouted and directly contracted promising high school athletes without a centralized selection process. The Phillies, impressed by his raw athleticism, speed, and hitting ability demonstrated in amateur showcases, viewed him as a high-upside prospect for outfield development.[6][7]Minor League Career

Signing and Initial Development

Johnson was signed as an amateur free agent by the Philadelphia Phillies on July 11, 1961, under the recommendation of scout Tony Lucadello, who identified his potential during high school play in Detroit.[6][2] His professional debut came in 1962 with the Class D Miami Marlins of the Florida State League, where he batted .313 with 135 hits in 431 at-bats over 113 games, earning the league batting title and recording 19 outfield assists.[8][2] This performance highlighted his contact hitting and defensive range early in his development. Advancing to Class A in 1963, Johnson joined the Magic Valley Cowboys in the Pioneer League, posting a .329 average with 155 hits in 471 at-bats across 120 games, along with 35 home runs and 128 RBIs, which earned him league MVP honors and led the circuit in hits.[8][2] His power surge and run production demonstrated rapid adaptation to higher competition, solidifying his prospect status within the Phillies' system.[2] By 1964, Johnson reached Triple-A with the Arkansas Travelers of the Pacific Coast League, batting .316 with 111 hits in 351 at-bats over 90 games, including 21 home runs and 71 RBIs, before being recalled to the majors in late July.[8][2] This three-year ascent from rookie ball to the upper minors, marked by consistent averages above .313 and emerging power, reflected the Phillies' aggressive promotion of his offensive skills, though his fielding remained a noted area for refinement.[7][2]Key Minor League Performances

Johnson's breakthrough in the minor leagues came in 1963 with the Magic Valley Cowboys of the Class A Pioneer League, where he batted .329 with 35 home runs and 128 RBIs, leading the league in both power categories and posting an OPS of 1.034; he was voted the league's Most Valuable Player for this performance.[8][2] In 1962, his professional debut season with the Class D Miami Marlins of the Florida State League, Johnson hit .313, capturing the league batting title while adding 5 home runs, 60 RBIs, and 19 outfield assists, demonstrating early defensive promise alongside his offensive skills.[8][2] Advancing to Triple-A Arkansas Travelers in the Pacific Coast League in 1964, he maintained strong production at .316 with 21 home runs and 71 RBIs in 90 games (OPS .952) before his midseason promotion to the majors.[8][2] Later, after major league stints, Johnson returned to Triple-A in 1966 with the Tulsa Oilers (PCL), slashing .355/.425/.578 with 14 home runs and 56 RBIs in 80 games (OPS 1.003), highlighting his continued hitting ability at the highest minor league level.[8]| Season | Team (League) | AVG | HR | RBI | OPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Miami (FSL) | .313 | 5 | 60 | .798 |

| 1963 | Magic Valley (Pion) | .329 | 35 | 128 | 1.034 |

| 1964 | Arkansas (PCL) | .316 | 21 | 71 | .952 |

| 1966 | Tulsa (PCL) | .355 | 14 | 56 | 1.003 |

Major League Career

Philadelphia Phillies (1964–1965)

Johnson was recalled from Triple-A Little Rock, where he had batted .316 with 21 home runs, and made his major league debut on July 25, 1964, against the St. Louis Cardinals in a 10-9 Phillies loss.[9][1] In his rookie season, he platooned in left field with veteran Wes Covington, appearing in 43 games with a .303 batting average, 4 home runs, and 18 RBIs over 109 at-bats.[1][9] Johnson hit near .400 during a six-week stretch but struggled defensively, earning the nickname "Iron Hands" for errors in the outfield while playing for the first-place Phillies amid their late-season collapse.[9] He contributed 3 home runs during September's 10-game losing streak that cost Philadelphia the National League pennant.[10] On October 2, 1964, against the Cincinnati Reds, Johnson made a spectacular catch in deep left field to rob Deron Johnson of extra bases, aiding a 10-0 Phillies victory that eliminated Cincinnati from pennant contention.[11] In 1965, Johnson continued platooning primarily against left-handed pitchers but began facing some right-handers, appearing in 97 games with a .294 batting average, 8 home runs, and 28 RBIs in 262 at-bats; he also played center field 9 times.[1][9] His defense showed slight improvement, though Phillies manager Gene Mauch grew frustrated with what he perceived as inconsistent effort.[9] On October 27, 1965, Philadelphia traded Johnson, along with pitcher Art Mahaffey and catcher Pat Corrales, to the St. Louis Cardinals for first baseman Bill White, shortstop Dick Groat, and catcher Bob Uecker.[6]St. Louis Cardinals and Cincinnati Reds (1966–1968)

Johnson joined the St. Louis Cardinals prior to the 1966 season as part of a multi-player trade from the Philadelphia Phillies in October 1965, which sent him along with pitcher Art Mahaffey and catcher Pat Corrales to St. Louis in exchange for first baseman Bill White, shortstop Dick Groat, and catcher Bob Uecker.[2] In 1966, he appeared in 25 games for the Cardinals, batting .186 with 16 hits in 86 at-bats, including 2 home runs and 6 RBIs.[1] His performance was underwhelming, leading to a demotion to Triple-A Tulsa in May, where he rebounded with a .355 batting average and 14 home runs over 80 games.[2] The following year, 1967, Johnson saw increased playing time with the Cardinals, appearing in 81 games and posting a .223 batting average with 39 hits in 175 at-bats, 1 home run, and 12 RBIs.[1] He was platooned in the outfield with Roger Maris and received limited action during the Cardinals' World Series victory over the Boston Red Sox, though his effort on the field drew criticism from observers.[2] On January 11, 1968, the Cardinals traded Johnson to the Cincinnati Reds in exchange for outfielder Dick Simpson.[6] With the Reds, Johnson experienced a career resurgence under manager Dave Bristol, securing the starting left field position and batting .312 in 149 games, with 188 hits in 603 at-bats, 2 home runs, 58 RBIs, a .342 on-base percentage, and a .395 slugging percentage—finishing fourth in the National League in batting average.[1][2] This performance earned him the Comeback Player of the Year award from The Sporting News.[2]California Angels (1969–1970)

Johnson was acquired by the California Angels on November 25, 1969, when the Cincinnati Reds traded him along with infielder Chico Ruiz to the Angels in exchange for pitchers Jim McGlothlin, Vern Geishert, and Pedro Borbon.[6] The deal came after Johnson had batted .315 with 11 home runs and 61 RBIs in 139 games for the Reds during the 1969 season, marking his second straight year over .300 but amid growing concerns about his inconsistent effort.[1] In 1970, Johnson emerged as the Angels' standout left fielder, appearing in 156 games while posting a .329 batting average on 186 hits, including 32 doubles, one triple, 14 home runs, 84 RBIs, and 85 runs scored.[1] He started the season hot, leading the American League with a .366 average through May, earned selection to the All-Star Game, and maintained a consistent line-drive swing that emphasized contact over power.[12] Despite cooling off later, Johnson clinched the AL batting title on October 1, 1970, against the Chicago White Sox, going 2-for-3 in the Angels' 4-0 win to finish at .3289, edging Boston's Carl Yastrzemski (.3286) by .0003 points—the closest margin in league history at the time and the franchise's first batting crown.[13]Cleveland Indians, Texas Rangers, New York Yankees, and Detroit Tigers (1973–1975)

On March 8, 1973, the Cleveland Indians traded Johnson to the Texas Rangers in exchange for pitchers Vince Colbert and Rich Hinton.[6] With the Rangers, Johnson had a solid season, appearing in 158 games primarily as a designated hitter and left fielder, batting .287 with 179 hits, 8 home runs, and 68 RBIs.[1] He performed under managers Whitey Herzog and later Billy Martin, showing improved consistency compared to prior years.[7] In 1974, Johnson continued with the Rangers, posting a .291 average in 114 games with 132 hits, 4 home runs, and 41 RBIs before being benched by Martin for failing to run out ground balls, indicative of lingering effort concerns.[1][7] On September 9, he was sold to the New York Yankees, where he played 10 games, hitting .214 with 6 hits, 1 home run, and 2 RBIs.[1] Johnson returned to the Yankees in 1975, playing 52 games with a .261 average, 31 hits, 1 home run, and 15 RBIs, amid a decline in production and fewer reported confrontations.[1] He was released on September 4, 1975, ending his Yankees tenure.[6] These years marked Johnson's transition to journeyman status, with respectable but unremarkable output as teams managed his role amid past behavioral issues.[9]Grievance, Suspension, and Arbitration

1971 Suspension for Mental Disability

In early 1971, Alex Johnson exhibited inconsistent effort and subpar performance for the California Angels, batting .264 with two home runs and 23 RBIs through late June, a sharp decline from his .329 American League batting title-winning season in 1970.[14] [2] He had been benched five times and fined on 29 occasions by manager Lefty Phillips for perceived lapses in concentration and hustle, including incidents where he failed to run out ground balls aggressively or appeared disengaged during games.[2] [15] On June 26, 1971, Angels general manager Dick Walsh suspended Johnson indefinitely without pay under major league rules for "not giving an adequate effort on the playing field," extending beyond the team's 30-day maximum disciplinary period after Commissioner Bowie Kuhn placed him on the restricted list.[14] [2] The suspension stemmed from documented behaviors such as loafing on plays, verbal confrontations with coaches, and refusal to participate fully in drills, which the club attributed to willful underperformance rather than physical injury.[2] [7] The Major League Baseball Players Association, led by executive director Marvin Miller, immediately filed a grievance on Johnson's behalf, contending that his issues arose from an "emotional disturbance" or mental disability warranting placement on the disabled list with full salary rather than punitive suspension.[7] [2] Miller, after interviewing Johnson extensively, described him as "obviously emotionally disabled" due to underlying stress and psychological factors, arguing that such conditions merited medical treatment and pay protection equivalent to physical ailments, a novel claim at the time given the era's limited recognition of mental health in sports contracts.[2] This framing shifted the narrative from disciplinary failure to a health-related incapacity, prompting psychiatric evaluations as part of the proceedings.[7]Arbitration Ruling and Implications

In September 1971, arbitrator Lewis Gill ruled in favor of Alex Johnson in his grievance against the California Angels, determining that Johnson's emotional condition constituted a disability equivalent to a physical injury under the collective bargaining agreement.[2][16] The decision awarded Johnson $29,970 in back pay for the period he spent on the restricted list following his June 26 suspension without pay, as players on the disabled list received full salary.[2][16] However, Gill upheld the Angels' imposition of $3,750 in fines for Johnson's prior on-field misconduct, rejecting the union's challenge to those penalties.[2][7] The ruling stemmed from testimony by two psychiatrists—one selected by the Major League Baseball Players Association and one by the Angels—who independently diagnosed Johnson with an emotional disturbance impairing his ability to perform, supporting the grievance that the suspension violated disability protections.[2][5] This outcome reinstated Johnson to active status, removing him from the restricted list, though he did not return to play for the Angels that season.[16][7] The arbitration established a precedent in professional baseball for recognizing mental health issues as qualifying disabilities eligible for salary continuation, akin to physical ailments, which compelled MLB to formalize procedures for evaluating psychological impairments.[2][17] Critics within the league, including team owners, expressed concerns that the decision could incentivize players to attribute performance lapses or disciplinary issues to unverifiable mental conditions, potentially undermining accountability for effort and conduct.[7] Despite these reservations, the ruling influenced subsequent labor negotiations, embedding mental health provisions into union contracts and broadening the scope of player protections beyond overt physical injuries.[2][17]Career Aftermath and Trades

Following his reinstatement by arbitrator Peter Seitz in September 1971, which ruled that the California Angels must accommodate Johnson's mental health needs under their collective bargaining agreement, the team traded him on October 5, 1971, to the Cleveland Indians along with catcher Jerry Moses in exchange for outfielders Vada Pinson and Frank Baker and pitcher Alan Foster.[2][6] Johnson appeared in 108 games for Cleveland in 1972, batting .255 with four home runs and 33 RBI, a marked decline from his 1970 American League batting title and MVP-caliber performance.[2][1] On March 8, 1973, prior to the season, the Indians traded Johnson to the Texas Rangers for pitchers Rich Hinton and Vince Colbert, as Cleveland sought to move the 30-year-old outfielder amid ongoing concerns over his inconsistent effort and clubhouse disruptions.[6][18] In 158 games split between designated hitter and outfield duties for Texas in 1973, Johnson hit .252 with 10 home runs and 59 RBI, providing average production but drawing criticism from manager Whitey Herzog for lapses in hustle.[2][1] He remained with the Rangers into 1974, batting .190 in 70 games before the team sold his contract to the New York Yankees on September 9, 1974, for an undisclosed sum, allowing Texas to shed a veteran whose production had eroded.[6][19] Johnson played sparingly for the Yankees in 1974 and 1975, appearing in 64 games total with a .214 batting average, two home runs, and 16 RBI, primarily as a designated hitter and pinch-hitter amid a roster crowded with established outfielders.[1] The Yankees released him on September 4, 1975, effectively ending his viability as a regular player at age 32.[6] He signed a minor-league contract with the Detroit Tigers on January 7, 1976, and made the Opening Day roster, but managed only a .196 average in 50 games before retiring at season's end, concluding a 13-year major league career with 1,341 hits, 65 home runs, and a .259 batting average.[6][2] The rapid succession of trades and diminished role underscored the lasting impact of the 1971 suspension, as teams viewed Johnson as a high-risk asset despite his proven batting skill, prioritizing roster stability over potential rehabilitation.[2]Controversies and Criticisms

Questions of Effort and Professionalism

Throughout his tenure with the California Angels, particularly in 1970 and 1971, Alex Johnson faced repeated accusations of insufficient effort on the field, including failing to run out ground balls and displaying a lackadaisical approach during plays.[7] Angels manager Lefty Phillips benched Johnson on multiple occasions for not hustling, with teammates observing instances where he jogged rather than sprinted, leading to suspicions of deliberate underperformance or "dogging it."[20] These behaviors culminated in Johnson's indefinite suspension without pay on June 26, 1971, after a series of incidents deemed by the Angels as "failure to hustle and improper mental attitude," marking the third such disciplinary action that season.[14][2] The team's management, including general manager Dick Meyer, argued that Johnson's actions violated professional standards, as he had been fined and warned previously for similar lapses following his 1970 batting title.[21] Critics within baseball, including some players and executives, viewed these episodes as evidence of poor professionalism, contrasting sharply with Johnson's undeniable hitting talent, which had earned him a .329 average and American League batting championship the prior year.[21] Johnson's defenders, including the Major League Baseball Players Association, contested the suspension by attributing his conduct to emotional distress rather than willful negligence, a claim upheld in arbitration on September 21, 1971, which reinstated him with back pay after psychiatric evaluations confirmed a disabling condition.[2][5] However, skepticism persisted among Angels personnel and observers, who questioned whether the ruling excused broader accountability issues, as Johnson's post-reinstatement performance and subsequent trades reflected ongoing team dissatisfaction with his reliability and clubhouse demeanor.[7][21] This episode fueled debates in baseball circles about distinguishing genuine mental health challenges from lapses in professional discipline, with some contemporaries arguing that Johnson's talent masked deeper motivational shortcomings.[4]Chico Ruiz Pistol Incident

On June 13, 1971, during the ninth inning of a California Angels game against the Washington Senators at Anaheim Stadium—which the Angels lost 5-2—outfielder Alex Johnson accused teammate Chico Ruiz of pulling a .38-caliber handgun from his locker and waving it menacingly at him in the clubhouse.[22][23] Both players had been used as pinch hitters earlier in the contest, and the accusation stemmed from ongoing clubhouse friction amid Johnson's documented struggles with effort and mental health.[24][7] Ruiz, a utility infielder, immediately denied the charge, claiming he did not own any firearm, let alone a cap pistol.[25] The Angels' front office launched an internal investigation, but initial findings cleared Ruiz, exacerbating team divisions as at least three other Angels players reportedly carried guns amid the era's heightened tensions.[14][26] Later revelations confirmed Johnson's account: under oath during arbitration proceedings related to Johnson's suspension, Angels executive Robert Walsh admitted that Ruiz had indeed brandished an unloaded pistol at Johnson and that a cover-up had been attempted to protect team harmony.[15][27] This incident underscored the Angels' dysfunctional 1971 season, where interpersonal conflicts compounded Johnson's performance issues, leading to his indefinite suspension four days later for "failure to give his best effort," rather than directly for the altercation.[14][3]Broader Debates on Accountability vs. Mental Health

The case of Alex Johnson's 1971 suspension by the California Angels and Major League Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn exemplified tensions between enforcing player accountability for perceived lack of effort and recognizing mental health impairments as legitimate disabilities. The Angels suspended Johnson indefinitely without pay on June 23, 1971, citing "mental disability" manifested in inconsistent performance, failure to run out plays, and confrontations with management, which they initially framed as willful neglect of duties rather than a medical condition.[2] Kuhn upheld the suspension, emphasizing the need to maintain competitive standards and deter similar behaviors, arguing that professional athletes must demonstrate consistent effort regardless of personal challenges.[7] The Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA), led by executive director Marvin Miller, contested the suspension through grievance arbitration, asserting that Johnson's behaviors stemmed from an diagnosable emotional disturbance rather than laziness or defiance. Psychiatrists testifying on Johnson's behalf diagnosed him with a severe anxiety-related condition exacerbated by performance pressure, leading the arbitration panel to rule on September 21, 1971, that his issues qualified as a disability equivalent to physical injury, entitling him to back pay, reinstatement, and placement on the disabled list.[28] [2] This landmark decision marked the first time MLB formally equated mental health conditions with physical ones for labor protections, setting a precedent that expanded union leverage in disciplinary disputes and compelled teams to incorporate psychological evaluations.[28] Johnson's arbitration outcome fueled broader discussions in professional sports about the verifiability of mental health claims versus the imperatives of team discipline and fan expectations for maximum effort. Critics within baseball management, including Angels owner Gene Autry, contended that the ruling risked incentivizing underperformance by allowing subjective psychiatric testimony to override observable lapses in professionalism, potentially eroding accountability in a merit-based industry.[7] Proponents, including Miller, highlighted the ruling's role in destigmatizing mental illness, arguing that pre-1971 practices often misattributed psychological struggles to character flaws, as evidenced by Johnson's prior diagnoses and inconsistent career output despite elite talent like his 1970 American League batting title (.329 average).[2] [7] Subsequent analyses noted the case's influence on sports psychology protocols, prompting MLB to integrate mental health support but also perpetuating skepticism over distinguishing genuine disorders from motivational deficits, a challenge echoed in later high-profile cases involving player effort and behavioral issues.[2]Post-Retirement

Later Activities and Business Ventures

Following his final Major League Baseball season with the Detroit Tigers in 1976, Johnson played one additional professional season in 1977 with the Mexico City Reds of the Mexican League, where he batted .321 in 54 games.[2] By 1978, he had returned to his hometown of Detroit, Michigan, to manage his father's truck repair and leasing company.[2] Johnson expressed interest in the trucking business during his playing days and fully assumed ownership after his father's death in 1985.[7] [2] The company, which handled repair services and vehicle leasing, represented Johnson's primary post-baseball occupation, reflecting a shift from athletic pursuits to family-inherited entrepreneurship.[5] He maintained a low public profile in this venture, avoiding involvement in baseball-related events or media until a rare appearance at the 2015 Jerry Malloy Negro Leagues Conference in Detroit.[7]Death and Final Years

Johnson spent his post-baseball years managing the family-owned Johnson Trucking Service in the Detroit area, a company originally established by his father, Arthur Johnson, in the 1940s for truck repair, leasing, and renting dump trucks to construction firms.[29] [2] He assumed control of the business in the early 1980s following his father's death and expressed satisfaction with this endeavor in a 1998 Sports Illustrated interview, stating it represented "the thing I've always wanted."[4] Johnson largely avoided the public eye in his later decades, residing in the Detroit region where he had been raised and attended Northwestern High School.[5] Johnson died on February 28, 2015, in Detroit, Michigan, at age 72 from complications of prostate cancer, according to his son, Alex Johnson Jr.[30] [5] He was survived by his daughter, Jenifer, and son, Alex Jr.[5] Johnson was interred at Mount Hope Memorial Gardens in Livonia, Michigan.[1]Personal Life

Family and Relationships

Johnson was born on December 7, 1942, in Helena, Arkansas, to Arthur Johnson Sr., who initially worked in an auto plant before owning a truck repair and leasing company; his father died in 1985.[2] He had four siblings, including two brothers and two sisters, among them Ron Johnson, a younger brother and All-Pro NFL running back primarily with the New York Giants, and sister Jean.[2][4][5] Johnson married Julia Augusta on February 2, 1962; the couple adopted daughter Jennifer in 1969 and had son Alex Jr. in 1972.[2] They divorced following the conclusion of his professional baseball career.[2] At the time of his death in 2015, Johnson was survived by daughter Jenifer and son Alex.[5] No other significant relationships are documented in available records.Health and Personal Struggles

Johnson's career was marked by significant mental health challenges, culminating in a 1971 arbitration ruling that recognized his emotional disability as equivalent to a physical injury. Two psychiatrists testified that he suffered from emotional incapacitation, leading to his retroactive placement on the disabled list with full pay after a suspension for lack of effort.[2][7][5] This landmark decision, supported by the Major League Baseball Players Association, stemmed from observed mood swings and inconsistent behavior, including fines for not hustling—29 instances by late June 1971—and conflicts with teammates and management.[2][4] In a 1990 interview, Johnson rejected claims of emotional illness, attributing his difficulties to dysfunctional team dynamics and "evil" influences rather than personal pathology.[5] These struggles contributed to interpersonal tensions, such as accusations of profanity toward teammates and a June 13, 1971, altercation involving teammate Chico Ruiz allegedly brandishing an unloaded pistol.[2] Post-retirement, Johnson expressed lasting bitterness toward baseball's handling of Black players and his own experiences, preferring a private life running a truck repair business inherited from his father in 1985.[7][2] On the family front, Johnson married Julia Augusta on February 2, 1962; they adopted a daughter, Jennifer, in 1969, and had a son, Alex Jr., in 1972, before divorcing after his playing days ended.[2] In his final years, he battled cancer, succumbing to complications on February 28, 2015, at age 72 in Detroit.[5][2][7]Legacy

Achievements and Statistical Highlights

Alex Johnson captured the American League batting title in 1970, posting a .329 average with 202 hits, including a league-leading 160 singles, over 633 at-bats for the California Angels.[12] [1] This performance marked the only batting championship in Angels franchise history and earned him a selection to the AL All-Star Game, along with an eighth-place finish in AL Most Valuable Player voting.[12] [21] He also received the Silver Bat Award that year, recognizing his offensive prowess as a left fielder.[31] Earlier, in 1968 with the Cincinnati Reds, Johnson rebounded from prior struggles to bat .310, securing The Sporting News National League Comeback Player of the Year Award.[31] [12] Across 13 major league seasons from 1964 to 1976, spanning teams including the Phillies, Cardinals, Reds, Angels, and Rangers, Johnson compiled a .288 career batting average, 1,331 hits, 78 home runs, 525 RBIs, and 550 runs scored in 1,286 games.[1] His on-base plus slugging (OPS) stood at .699, reflecting consistent contact hitting with modest power.[1] Johnson ranked among league leaders in batting average multiple times, finishing in the top 10 in 1968 (.310, NL) and 1969 (.315, NL).[12]| Season | Team | AVG | Hits | Notable Highlight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | CIN | .310 | 148 | NL Comeback Player of the Year[31] |

| 1970 | CAL | .329 | 202 | AL Batting Champion, All-Star[12] |

Viewpoints on Talent vs. Underachievement

Alex Johnson was widely regarded as one of the most naturally gifted hitters of his era, possessing exceptional bat speed honed through unconventional practice methods, such as hitting off a tee positioned 40 feet from home plate, and the ability to sprint from home to first base in 3.8 seconds.[7] His 1970 American League batting title, achieved with a .329 average and 202 hits—a California Angels franchise record that stood until 2000—underscored this talent, earning him All-Star selection and positioning him as a potential perennial .300 hitter capable of greater power output, as evidenced by his minor-league peaks of 35 home runs in Single-A and 21 in Triple-A.[2] [12] However, Johnson's career batting average settled at .288 over 13 seasons across nine teams, hampered by low walk rates, limited extra-base power relative to his physique (6 feet, 205 pounds), and subpar defensive play in the outfield, leading analysts to classify him as an underachiever whose frequent trades stemmed from inconsistent production and team frustrations.[7] [12] Managers and teammates frequently attributed Johnson's underperformance to a lack of effort rather than innate limitations, citing observable behaviors such as jogging after fly balls, failing to run out grounders, and displaying indifference during games.[2] California Angels manager Lefty Phillips remarked in 1971, "He’s got more ability than anyone on this club, but he doesn’t give a damn," following Johnson's suspension on June 26 for "failure to give his best effort" and conduct detrimental to the team, after he batted just .200 early that season amid visible disinterest.[3] Teammate Jim Fregosi echoed this, stating, "Alex has the talent to hit .350, but he doesn’t always hustle," while earlier managers like Dick Sisler in 1967 noted Johnson's lack of interest in improvement.[3] [2] These incidents, including clashes with peers and a 1966 demotion to the minors, fueled a reputation for surliness and alienation, with teams cycling him through lineups despite his hitting prowess.[12] In response to the 1971 suspension, which was indefinite and unpaid, an arbitrator ruled in Johnson's favor after two psychiatrists diagnosed him with an emotional disability requiring treatment akin to physical injury, marking a landmark victory for the MLB Players Association under Marvin Miller and establishing precedent for mental health considerations in labor disputes.[2] Johnson was reinstated with back pay on October 6, 1971, though he played only 64 more MLB games that year at a reduced .210 clip.[2] Proponents of this view, including Miller, framed it as humane treatment amid potential racial biases in team evaluations, yet critics among baseball personnel emphasized that Johnson's on-field apathy—evident in empirical lapses like not hustling—reflected personal accountability over systemic excuses, as his talent persisted but output did not when effort waned.[2] Post-career reflections, such as in a 1990 Los Angeles Times interview, revealed Johnson's lingering bitterness toward the sport, suggesting unresolved internal conflicts contributed to his failure to sustain elite performance.[21] Analyses portray Johnson as enigmatic, blending prodigious skills with self-sabotage: a warm personality off the field contrasted sharply with on-field anger, and while mental illness was cited, his career trajectory—solid but nomadic—implies that disciplined application could have elevated him to Hall of Fame contention rather than obscurity.[7] Teammate Rudy May captured the prevailing sentiment: "You owe it to the fans… to hustle at all times," highlighting how Johnson's selective disengagement undermined his gifts, a view substantiated by his journeyman status despite a .313 minor-league average and early MLB promise.[7][2]Career Statistics

Batting and Fielding Records

Alex Johnson compiled a career batting average of .288 over 13 major league seasons from 1964 to 1976, accumulating 1,331 hits in 1,331 games played.[1] [32] His offensive output included 78 home runs, 525 runs batted in, and 113 stolen bases, with an on-base plus slugging percentage of .718.[32] Johnson peaked in 1970 with the California Angels, leading the American League with a .329 batting average and earning an All-Star selection, while recording 202 hits, 14 home runs, and 86 RBI that year.[1]| Season | Team | G | AB | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | AVG | Notable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | PHI | 64 | 215 | 65 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 18 | .303 | Rookie season debut |

| 1968 | CIN | 151 | 602 | 188 | 27 | 7 | 7 | 58 | .312 | Franchise hits record (179 verified in some sources, but 188 total) |

| 1969 | CIN | 152 | 586 | 185 | 21 | 9 | 17 | 88 | .315 | Career-high RBI |

| 1970 | CAL | 158 | 614 | 202 | 33 | 3 | 14 | 86 | .329 | AL batting champion, All-Star |

| Career | - | 1,331 | 4,623 | 1,331 | 180 | 33 | 78 | 525 | .288 | - |