Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

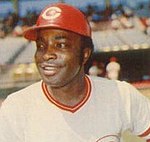

Joe Morgan

View on Wikipedia

Joe Leonard Morgan (September 19, 1943 – October 11, 2020) was an American professional baseball second baseman who played 22 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Houston Colt .45s / Astros, Cincinnati Reds, San Francisco Giants, Philadelphia Phillies, and Oakland Athletics from 1963 to 1984. He won two World Series championships with the Reds in 1975 and 1976 and was also named the National League Most Valuable Player in each of those years. Considered one of the greatest second basemen of all time, Morgan was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1990 in his first year of eligibility.

Key Information

After retiring as an active player, Morgan became a baseball broadcaster for the Reds, Giants, ABC, and ESPN, as well as a stint in the mid-to-late 1990s on NBC's postseason telecasts, teamed with Bob Costas and Bob Uecker. He hosted a weekly nationally syndicated radio show on Sports USA, while serving as a special advisor to the Reds.

Playing career

[edit]Morgan was African American[1] and the oldest of six children. Born in Bonham, Texas, he lived there until he was five years old. His family then moved to Oakland, California. Morgan was nicknamed "Little Joe" for his diminutive 5-foot-7-inch (1.70 m) stature. As a youth, he played American Legion baseball on a team sponsored by Post 471 in Oakland.[2] Morgan was a standout baseball player at Castlemont High School, but did not receive any offers from major league teams due to his size. He played college baseball at Oakland City College before being signed by the Houston Colt .45s as an amateur free agent in 1962, receiving a $3,000 signing bonus and a $500 per month salary.[3]

Houston Colt .45s/Astros

[edit]Morgan made his major league baseball debut on September 21, 1963.[3] Despite going on to win multiple World Series and MVPs for the Reds, he said his debut for the Colt .45s was the highlight of his career.[4]

Early in his career, Morgan struggled with his swing because he kept his back elbow down too low. Teammate Nellie Fox (also a stocky second baseman) suggested to Morgan that while at the plate he should flap his back arm like a chicken to keep his elbow up.[5] Morgan followed the advice, and his flapping arm became his signature.[3]

Morgan played his first nine major league seasons for the Houston Astros, compiling 72 home runs and 219 stolen bases. He was named an All-Star twice during this period, in 1966 and 1970. On June 25, 1966, Morgan was struck on the kneecap by a line drive (hit by Lee Maye) during batting practice.[6] The broken kneecap forced Morgan out of the lineup for 40 games, during which the Astros went 11–29 (for a .275 winning percentage).[7][8]

Although Morgan played with distinction for Houston, the Astros wanted more power in their lineup. Additionally, manager Harry Walker considered Morgan a troublemaker.[9] As a result, they traded Morgan to the Cincinnati Reds as part of a blockbuster multi-player deal on November 29, 1971, announced at baseball's winter meetings.[3]

Cincinnati Reds

[edit]To this day the aforementioned trade is considered an epoch-making deal for Cincinnati, although at the time many experts felt that the Astros got the better end of the deal.[10] Power-hitting Lee May, All-Star second baseman Tommy Helms, and outfielder/pinch hitter Jimmy Stewart went to the Astros. In addition to Morgan, included in the deal to the Reds were César Gerónimo (who became their regular right fielder and then center fielder), starting pitcher Jack Billingham, veteran infielder Denis Menke, and minor league outfielder Ed Armbrister. Morgan joined leadoff hitter Pete Rose as prolific catalysts at the top of the Reds' lineup. Morgan added home run power, not always displayed with the Astros in the cavernous Astrodome, outstanding speed and excellent defense.[11][12]

As part of the Big Red Machine, Morgan made eight consecutive All-Star Game appearances (1972–79) to go along with his 1966 and 1970 appearances with Houston. Morgan, along with teammates Pete Rose, Johnny Bench, Tony Pérez, and Dave Concepción, led the Reds to consecutive championships in the World Series. He drove in Ken Griffey for the winning run in Game 7 of the 1975 World Series. Morgan was also the National League MVP in 1975 and 1976.[13] He was the first second baseman in the history of the National League to win the MVP back to back.[14] In Morgan's NL MVP years he combined for a .324 batting average, 44 home runs, 205 runs batted in, 246 bases on balls, and 127 stolen bases.[15]

Morgan was an extremely capable hitter—especially in clutch situations. While his lifetime average was only .271, he hit between .288 and .327 during his peak years with the Reds. Additionally, he drew many walks, resulting in an excellent .392 on-base percentage. He also hit 268 home runs to go with his 449 doubles and 96 triples, excellent power for a middle infielder of his era, and was considered by some the finest base stealer of his generation (689 steals at greater than 80% success rate). Besides his prowess at the plate and on the bases, Morgan was an exceptional infielder, winning the Gold Glove Award in consecutive years from 1973 to 1977.[13] His short height proved an asset to him, as he had one of baseball's smallest strike zones. "The umpires gave him everything. If he didn't swing at the pitch, it was a ball," recalled Tommy John.[16]

Later career

[edit]Morgan returned to Houston in 1980 as a free agent on a reported contract of $255,000 for one season.[3] He helped the young Astros win the NL West, batting .243 in 141 games while leading the league in walks with 93. The Astros then lost the National League Championship Series to the Philadelphia Phillies. Morgan bristled with team manager Bill Virdon at being taken out in late innings for Rafael Landestoy. Late in the year, Morgan expressed to one reporter his doubt in playing for Virdon again.[17]

Morgan signed onto the San Francisco Giants for the next two seasons.[3] The 1982 season had a bumpy start for the team, but they were neck and neck for second place with the Los Angeles Dodgers (each behind Atlanta) with a three-game set to possibly determine the division race. The Dodgers eliminated San Francisco on the second-to-last day, but Morgan hit a go-ahead three run home run to give the Giants a lead they would not relinquish that saw Los Angeles eliminated in favor of the Braves winning the NL West; Morgan batted .240 and played in just 90 games, his lowest number of games played since 1968. Morgan won the 1982 Willie Mac Award for his spirit and leadership.[18] He batted .289 in 134 games the following season for the Giants.

Morgan was acquired along with Al Holland by the Phillies from the Giants for Mike Krukow, Mark Davis and minor-league outfielder C.L. Penigar on December 14, 1982.[19] He was reunited with former Reds teammates Pete Rose and Tony Pérez. The lineup was soon dubbed the "Wheeze Kids", referring to the considerable age in their starting lineup, where just one starting player was under 30 years old.[20] On his 40th birthday in 1983, Morgan had four hits, including two home runs and a double, at Veterans Stadium.[21]

The Phillies beat the Dodgers in the NLCS to reach the World Series for the second time in four seasons. Morgan got to play in the World Series for the final time, facing off against the Baltimore Orioles. In Game 1, he hit a home run in the sixth inning to tie the game; he became the second oldest player to hit a home run in the World Series (Enos Slaughter was a few months older at the age of 40). He went 5-for-19 in the Series, which included a second home run in Game 5, but the Phillies lost in five games.[22] Morgan finished his career with the Oakland Athletics in 1984, playing 116 games and batting .244. He collected a hit in his final game on September 30, collecting a double in his one at-bat before being taken out of the game.[3][23]

Post-playing career

[edit]Hall of Fame

[edit]In 1990, Morgan was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame with more than 81% of the vote. He entered together with Jim Palmer, both in their first year of eligibility. Morgan and Palmer were the 25th/26th players in MLB history to be elected in their first year of eligibility.[24]

In 2017, Morgan wrote a letter to the Hall of Fame in which he asked that players who had cheated by using performance-enhancing steroids not be elected into the Hall.[25]

Legacy

[edit]After his career ended, Morgan was inducted into the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame in 1987, and his jersey number 8 was retired. The Reds dedicated a statue for Morgan at Great American Ball Park in 2013.[26]

In the New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, Bill James named Morgan the best second baseman in baseball history, ahead of #2 Eddie Collins and #3 Rogers Hornsby. He also named Morgan as the "greatest percentages player in baseball history", due to his strong fielding percentage, stolen base percentage, walk-to-strikeout ratio, and walks per plate appearance.[27] The statement was included with the caveat that many players in baseball history could not be included in the formula due to lack of data. In the four decades since Morgan's retirement, only one player (Rickey Henderson) has had as many home runs and stolen bases as Morgan did for a career.[28] Morgan had at least 20 home runs and 50 stolen bases in the same season three times during his career,[29] including twice with at least 60 steals.[30]

In 1999, Morgan ranked Number 60 on The Sporting News' list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players,[31] and was nominated as a finalist for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.[32]

Morgan served as a member of the board of the Baseball Assistance Team, a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to helping former Major League, Minor League, and Negro league players through financial and medical hardships. In addition, since 1994, he served on the board of directors for the Baseball Hall of Fame, and was vice-chairman from 2000 until his death in 2020.[33]

Broadcasting career

[edit]Local gigs and college baseball

[edit]Morgan started his broadcasting career in 1985 for the Cincinnati Reds.[34] On September 11, 1985, Morgan, along with his television broadcasting partner Ken Wilson, was on hand to call Pete Rose's record-breaking 4,192nd career hit. A year later, Morgan started a nine-year stint as an announcer for the San Francisco Giants. Morgan added one more local gig when he joined the Oakland Athletics' broadcasting team for the 1995 season.[35]

In 1986, ESPN hired Morgan to call Monday Night Baseball and College World Series games.[36]

ABC Sports

[edit]From 1988 to 1989, Morgan served as an announcer for ABC, where he helped announce Monday Night and Thursday Night Baseball games (providing backup for the led announcing crew composed of Al Michaels, Tim McCarver, and Jim Palmer), the 1988 American League Championship Series[37] with Gary Bender and Reggie Jackson, and served as a field reporter for the 1989 World Series along with Gary Thorne (Morgan's regular season partner in 1989). Morgan was on the field at San Francisco's Candlestick Park alongside Hall of Famer Willie Mays (whom Morgan was getting set to interview) the moment the Loma Prieta earthquake hit.[38]

NBC Sports

[edit]From 1994 to 2000, Morgan teamed with Bob Costas and Bob Uecker (until 1997) to call baseball games on NBC (and in association with The Baseball Network from 1994 to 1995).[39][40] During this period, Morgan helped call three World Series (1995, 1997, and 1999) and four All-Star Games (1994, 1996, 1998, and 2000). Morgan also called three American League Championship Series (1996, 1998, and 2000) and three National League Championship Series (1995 alongside Greg Gumbel, 1997, and 1999).[35]

Morgan spent a previous stint (1986–1987) with NBC calling regional Game of the Week telecasts alongside Bob Carpenter.[41] During NBC's coverage of the 1985[42] and 1987 National League Championship Series, Morgan served as a pregame analyst alongside hosts Dick Enberg (in 1985)[43] and Marv Albert (in 1987).[44]

ESPN

[edit]

Morgan was a member of ESPN's lead baseball broadcast team alongside Jon Miller and Orel Hershiser. Besides teaming with Miller for Sunday Night Baseball (since its inception in 1990) telecasts, Morgan also teamed with Miller for League Championship Series and World Series broadcasts on ESPN Radio.[45][46]

In 1999, Morgan teamed with his then-NBC colleague Bob Costas to call two weekday night telecasts for ESPN. The first was on Wednesday, August 25 with Detroit Tigers playing against the Seattle Mariners. The second was on Tuesday, September 21 with the Atlanta Braves playing against the New York Mets.[47] He won two Sports Emmy Awards for Outstanding Sports Event Analyst in 1998 and 2005.[48]

In 2006, he called the Little League World Series Championship with Brent Musburger and Orel Hershiser on ABC, replacing the recently fired Harold Reynolds.[49] During the 2006 MLB playoffs, the network had Morgan pull double duty by calling the first half of the Mets–Dodgers playoff game at Shea Stadium before traveling across town to call the Yankees–Tigers night game at Yankee Stadium.[50]

In 2009, Sports Illustrated's Joe Posnanski spoke about the perceived disparity between Morgan's celebrated playing style and his on-air persona:

- "The disconnect between Morgan the player and Morgan the announcer is one that I'm just not sure anyone has figured. Bill James tells a great story about how one time Jon Miller showed Morgan Bill's New Historical Baseball Abstract, which has Morgan ranked as the best second baseman of all time, ahead of Rogers Hornsby. Well, Morgan starts griping that this was ridiculous, that Hornsby hit .358 in his career, and Morgan never hit .358, and so on. And there it was, perfectly aligned—Joe Morgan the announcer arguing against Joe Morgan the player."[51]

In the wake of Morgan taking an official role with the Cincinnati Reds as a "special adviser to baseball operations", it was announced on November 8, 2010, that Morgan would not be returning for the 2011 season as an announcer on ESPN Sunday Night Baseball. His former broadcast partner Jon Miller's contract expired in 2010 and ESPN chose not to renew his contract. Morgan and Miller were replaced by Bobby Valentine and Dan Shulman, respectively (while ESPN retained Orel Hershiser, who joined the Sunday Night Baseball telecasts in 2010).[52]

Other appearances

[edit]Morgan was also a broadcaster in the MLB 2K video game series from 2K Sports.[53]

It was announced on June 17, 2011, that Morgan would begin a daily, one-hour general-sports-talk radio program on Sports USA Radio Network, beginning on August 22 of that year.[54]

Return to the Reds

[edit]In April 2010, Morgan returned to the Reds as an advisor to baseball operations, including community outreach for the Reds.[55]

Personal life

[edit]Morgan married Gloria Stewart, his high school girlfriend, on April 3, 1967. They had two children, and divorced in the 1980s. He then married Theresa Behymer in 1990. They had twins in 1991.[3]

In March 1988, while transiting through Los Angeles International Airport, Morgan was violently thrown to the floor, handcuffed, and arrested by Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) detectives who profiled him as a drug courier.[1] He filed and won a civil rights case against the LAPD in 1991,[56] and was awarded $540,000.[57] In 1993, a federal court upheld his claim that his civil rights had been violated.[58]

In 2015, Morgan was diagnosed with Myelodysplastic syndrome, which developed into leukemia. He received a bone marrow transplant from one of his daughters.[59] Morgan died on October 11, 2020, at the age of 77, at his home in Danville, California. He suffered from a non-specified polyneuropathy in the time leading up to his death.[60][61] Behymer-Morgan survives him.

See also

[edit]- Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame

- Houston Astros award winners and league leaders

- List of Gold Glove middle infield duos

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career total bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball single-game hits leaders

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Joe Morgan's Suit Protests 'Profile of Drug Dealer' That Led to Arrest : Civil rights: The former baseball star says he was unfairly targeted by police and detained at LAX because he is black. A second trial on his claim is set". Los Angeles Times. August 11, 1990.

- ^ "Joe Morgan (1943–2020)". The American Legion Magazine. 189 (6). American Legion: 8. December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Faber, Charles F. "Joe Morgan". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Joe Morgan, early Astros All-Star, dies". MLB.com. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ Jauss, Bill. "Morgan A Tribute To Game's 'Little Men': One Of His Idols Was Nellie Fox," Chicago Tribune (August 5, 1990).

- ^ "1966 – Timeline," Astros Daily. Accessed June 25, 2012.

- ^ "Joe Morgan 1966 Batting Game Log". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "1966 Houston Astros Schedule". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Purdy, Dennis (2006). The Team-by-Team Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. New York City: Workman Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7611-3943-5.

- ^ Neyer, Rob (2006). Rob Neyer's Big Book of Baseball Blunders. Simon & Schuster. p. 193.

- ^ Posnanski, Joe (March 6, 2020). "The Baseball 100: No. 21, Joe Morgan". The Athletic. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

[H]e hit 13 homers in '71 – and didn't appreciate that he played half his home games in the hitters' dungeon that was the Houston Astrodome.

(subscription required) - ^ "Joe Morgan". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved October 12, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Hall of Famer Joe Morgan, one of Oakland's greatest players, dies at 77". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Great Baseball Feats, Facts and Figures, 2008 Edition, p. 152, David Nemec and Scott Flatow, A Signet Book, Penguin Group, New York, ISBN 978-0-451-22363-0

- ^ "The Red Sox have made two of the best trades in baseball history". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ John, Tommy; Valenti, Dan (1991). TJ: My Twenty-Six Years in Baseball. New York: Bantam. p. 275. ISBN 0-553-07184-X.

- ^ "Second baseman Joe Morgan, who told a reporter he".

- ^ Schulman, Henry (October 2, 2015). "Why Giants players, fans care so much about Willie Mac Award". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Phillies trade Krukow, 2 others for Morgan, Holland," United Press International (UPI), Tuesday, December 14, 1982. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ "Pennant-winning "Wheeze Kids"". MLB.com.

- ^ "Chicago Cubs at Philadelphia Phillies Box Score, September 19, 1983". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference. Retrieved April 24, 2021.

- ^ "1983 World Series - Baltimore Orioles over Philadelphia Phillies (4-1)".

- ^ "Kansas City Royals vs Oakland Athletics Box Score: September 30, 1984".

- ^ "Every first-ballot Hall of Famer in MLB history". MLB.com.

- ^ "Joe Morgan wrote a letter asking Hall of Fame voters not to support PED users". November 21, 2017.

- ^ Warnemuende, Jeremy (September 7, 2013). "Reds unveil Morgan's statue before Saturday's game". MLB.com. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 479–481.

- ^ "Baseball keeps losing legends in 2020, and Joe Morgan might have been the smallest and mightiest of them all". ESPN.com. October 12, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Wittenmyer, Gordon (August 6, 2024). "Here's the story behind how Elly De La Cruz is making Reds history after win over Marlins". Cincinnati Enquirer – via AOL.

- ^ "Reds' Elly De La Cruz becomes fifth player to reach 20 HRs, 60 SB in a season". Sportsnet. August 21, 2024. Retrieved December 29, 2024.

- ^ "Baseball's 100 Greatest Players". The Sporting News. 1998. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ^ "The All-Century Team | MLB.com". Mlb.mlb.com. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Board of Directors". Baseball Hall of Fame.

- ^ Nightengale, Bobby (October 12, 2020). "Cincinnati Reds Hall of Famer Joe Morgan dies at 77". The Columbus Dispatch.

- ^ a b Casselberry, Ian (October 12, 2020). "Joe Morgan, Hall of Fame baseball player and acclaimed broadcaster, passes away at 77". Awful Announcing.

- ^ "Joe Morgan and Jay Johnstone, a pair of former major league". The Associated Press. March 7, 1986. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Sarni, Jim (October 7, 1988). "ABC Is Good Or Bad, Depending On Series". Sun Sentinel. South Florida. Archived from the original on April 16, 2015.

- ^ "Will Clark, Matt Williams Reflect on 1989 Quake". NBC Bay Area. October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Kent, Milton (October 14, 1996). "Costas-Morgan-Uecker, talent combo that works". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Hirsley, Michael (June 2, 1998). "Uecker Quits; NBC Won't Replace Him". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ 1987-09-19 NBC GOW Intro_Cincinnati Reds at San Francisco Giants on YouTube

- ^ 1985 10 09 1985 NLCS Game 1 St. Louis Cardinals at Los Angeles on YouTube

- ^ Goodwin, Michael (October 15, 1985). "Scully's Team the Winner in Playoffs". The New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Highlights". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. October 6, 1987. p. 45. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

Marv Albert tackles the pre-game show assignment with Joe Morgan.

- ^ Baggarly, Andrew (April 19, 2020). "'A national treasure': How 'Sunday Night Baseball' got its start 30 years ago". The Athletic. Retrieved October 12, 2020. (subscription required)

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (November 11, 2010). "ESPN Bids Miller and Morgan a Not-So-Fond Farewell". The New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Media Notes". Sports Business Daily. Advance Publications. August 25, 1999. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Joe Morgan". Emmy Awards. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ^ "People & Personalities: Joe Morgan Replaces Reynolds On LLWS". Sports Business Journal. August 4, 2006. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ^ "Networks take N.Y. minute to decide baseball's two postseason money series". USA Today. October 2, 2006. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ Roth, David (September 26, 2009). "The Sportswriting Machine". Gelf Magazine. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ^ Richard Sandomir (November 11, 2010). "ESPN Bids Miller and Morgan a Not-So-Fond Farewell – The New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Bumbaca, Chris (October 12, 2020). "Hall of Famer, Big Red Machine second baseman Joe Morgan dies at 77". USA Today. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Martin, Cam (June 17, 2011). "Joe Morgan Getting New Weekday Radio Show". Adweek. Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ^ Sheldon, Mark (April 21, 2010). "Morgan returns to Reds as advisor". reds.mlb.com. Retrieved July 10, 2017.[dead link]

- ^ "Joe Morgan testifies". The Hour. February 12, 1991.

- ^ "Judge Upholds Award Given to Joe Morgan". Los Angeles Times. April 30, 1991.

- ^ "Joe Morgan, Plaintiff-appellee, v. Bill Woessner, Defendant,andclay Searle; Los Angeles City, Defendants-appellants (two Cases), 997 F.2d 1244 (9th Cir. 1993)". www.law.justia.com. June 10, 1993.

- ^ Poole, Monte (June 19, 2020). "How Joe Morgan's brush with leukemia gave Father's Day a new meaning" (Giants). NBC Sports. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Kay, Joe (October 12, 2020). "Joe Morgan, driving force of Big Red Machine, dies at 77". Associated Press. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Bobby Nightengale (October 12, 2020). "Cincinnati Reds Hall of Famer Joe Morgan dies at 77". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

External links

[edit]- Joe Morgan at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from MLB · ESPN · Baseball Reference · Fangraphs · Baseball Reference (Minors) · Retrosheet · Baseball Almanac

- Joe Morgan at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- San Francisco Chronicle – Joe Morgan's clutch homer knocked the Dodgers out of the pennant race on the final day of the 1982 season and made the Braves champions.

Joe Morgan

View on GrokipediaEarly life and education

Childhood, family, and entry into baseball

Joe Leonard Morgan was born on September 19, 1943, in Bonham, Texas, the oldest of six children born to Leonard Morgan, a worker in the tire and rubber industry, and Ollie Mae Morgan.[2][4] The family relocated to Oakland, California, when Morgan was five years old, seeking better economic opportunities in the postwar period.[2][4] In Oakland, Morgan's father took employment at local shipyards, contributing to the family's stability amid the challenges faced by many African American households migrating from the South.[2] Morgan developed a passion for baseball during his youth in Oakland, initially playing sandlot games before joining organized youth leagues around age 13.[5] He idolized second basemen like Jackie Robinson and Nellie Fox, though he primarily played shortstop.[6] At Castlemont High School, Morgan emerged as a standout infielder, batting for average and power while stealing bases effectively, and leading the team to an Oakland city championship.[2][4] Despite his high school success, scouts overlooked him due to his diminutive frame—standing 5 feet 7 inches and weighing around 150 pounds—which limited scholarship offers from colleges.[2][7] After graduating from Castlemont in 1962 and briefly attending Merritt College (also known as Oakland City College), Morgan entered professional baseball when the expansion Houston Colt .45s signed him as an amateur free agent on November 1, 1962—the pre-draft era allowing teams to sign uncommitted prospects directly.[8][7] The contract included a modest $3,000 signing bonus and $500 monthly salary during the season, reflecting the risks for a lightly scouted player.[9] Morgan began his minor league career in 1963 with the Modesto Colts of the Class C California League and the Durham Bulls of the Class A Carolina League, where he batted over .300 in both stops, demonstrating the skills that would define his major league tenure.[4][10]Professional playing career

Houston Colt .45s / Astros (1963–1971)

Joe Morgan signed with the Houston Colt .45s as an amateur free agent on November 1, 1962.[11] He made his major league debut on September 21, 1963, appearing in eight games that season while batting .240 with five walks.[3] Limited to 10 games in 1964 due to minor league seasoning, Morgan recorded a .189 average.[3] Morgan secured the regular second base role in 1965, playing 157 games and posting a .271 batting average with 14 home runs, 97 walks, and a .373 on-base percentage, finishing second in [National League](/page/National League) Rookie of the Year voting.[3] He earned All-Star selections in 1966 (.285 average, 89 walks) and 1970 (.268 average, 42 stolen bases).[3][12] A broken wrist limited him to 10 games in 1968, but he rebounded in 1969 with 49 stolen bases and 110 walks.[3] Defensively, Morgan's fielding percentage at second base improved steadily, reaching .986 in 1971 with only 12 errors in 830 chances.[3] His 1971 season featured a .256 average, 13 home runs, 40 stolen bases, and 88 walks.[3]| Year | Games | AVG | HR | RBI | SB | BB | OBP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | 8 | .240 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 5 | .367 |

| 1964 | 10 | .189 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | .302 |

| 1965 | 157 | .271 | 14 | 40 | 20 | 97 | .373 |

| 1966 | 122 | .285 | 5 | 42 | 11 | 89 | .410 |

| 1967 | 133 | .275 | 6 | 42 | 29 | 81 | .378 |

| 1968 | 10 | .250 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 | .444 |

| 1969 | 147 | .236 | 15 | 43 | 49 | 110 | .365 |

| 1970 | 144 | .268 | 8 | 52 | 42 | 102 | .383 |

| 1971 | 160 | .256 | 13 | 56 | 40 | 88 | .351 |

Cincinnati Reds (1972–1977)

On November 29, 1971, the Cincinnati Reds acquired Joe Morgan from the Houston Astros in an eight-player trade, receiving Morgan along with infielder Denis Menke, pitchers Jack Billingham and Ed Armbrister, and outfielder César Gerónimo in exchange for outfielder Lee May, second baseman Tommy Helms, and utility infielder Jimmy Stewart.[3] This deal bolstered the Reds' lineup with Morgan's speed, on-base skills, and defense, contributing to the emergence of the "Big Red Machine" dynasty.[1] In his debut season of 1972, Morgan led the National League in runs scored (122), walks (115), and on-base percentage (.417), while batting .292 with 58 stolen bases, earning his first All-Star selection with the Reds and finishing fourth in MVP voting.[3][1] Morgan's tenure from 1972 to 1977 solidified his status as a cornerstone of the Reds' powerhouse offense and defense. He achieved elite production, averaging a .319 on-base plus slugging percentage above .900 annually, with consistent power (minimum 16 home runs per season) and base-stealing prowess (at least 49 steals each year). Defensively, he won five consecutive Gold Glove Awards from 1973 to 1977 for his exceptional play at second base. His leadership and versatility ignited the lineup alongside stars like Pete Rose and Johnny Bench, driving the team's sustained contention.[3][1]

| Year | Games | AVG | OBP | SLG | HR | RBI | SB | BB | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 149 | .292 | .417 | .435 | 16 | 73 | 58 | 115 | 122 |

| 1973 | 157 | .290 | .406 | .493 | 26 | 82 | 67 | 111 | 116 |

| 1974 | 149 | .293 | .427 | .494 | 22 | 67 | 58 | 120 | 107 |

| 1975 | 146 | .327 | .466 | .508 | 17 | 94 | 67 | 132 | 107 |

| 1976 | 141 | .320 | .444 | .576 | 27 | 111 | 60 | 114 | 113 |

| 1977 | 153 | .288 | .417 | .478 | 22 | 78 | 49 | 117 | 113 |

Later teams (1978–1984)

Morgan remained with the Cincinnati Reds for the 1978 and 1979 seasons, earning All-Star selections in both years despite a decline in performance following his MVP peaks. In 1978, he batted .236 with 13 home runs and 75 RBIs over 132 games, hampered by an abdominal muscle injury that affected his speed and average.[3][13] His 1979 output included a .250 batting average, 9 home runs, and 32 RBIs in 127 games, with 28 stolen bases.[3] As a free agent after the 1979 season, Morgan signed a one-year contract with the Houston Astros, returning to the organization where he began his career.[14] In 1980, he posted a .243 average, 11 home runs, 49 RBIs, and 24 stolen bases in 141 games, contributing to the Astros' National League West division title but exiting in the NLCS.[3] Morgan joined the San Francisco Giants on February 9, 1981, signing as a free agent and providing veteran leadership during a strike-shortened season where he batted .240 with 8 home runs in 90 games.[15][3] In 1982, he experienced a resurgence at age 39, hitting .289 with 14 home runs, 61 RBIs, and 24 stolen bases in 134 games, earning the Silver Slugger Award and finishing 16th in National League MVP voting.[3] His performance helped the Giants achieve back-to-back winning seasons for the first time since 1970–1971, contending for the NL West title with a 90–72 record; notable contributions included a home run against the Dodgers that impacted their playoff hopes.[16][17] Acquired by the Philadelphia Phillies from the Giants along with pitcher Al Holland ahead of the 1983 season, Morgan batted .230 with 16 home runs and 59 RBIs in 123 games, providing power from the second base position. The Phillies advanced to the World Series, defeating the Dodgers in the NLCS before losing to the Baltimore Orioles in five games.[3] Released by the Phillies after the World Series, Morgan signed with the Oakland Athletics before the 1984 season, his final year as a player.[4] He batted .244 with 6 home runs and 43 RBIs in 116 games, retiring at age 40 after the season.[3]Awards, statistics, and Hall of Fame

Major awards and achievements

Joe Morgan won the National League Most Valuable Player Award in both 1975 and 1976, leading the Cincinnati Reds to consecutive World Series titles while posting elite offensive and defensive numbers, including a .327 batting average, 27 home runs, and 111 runs batted in during the 1976 season.[3] [1] He became the first second baseman to capture back-to-back MVP honors since Jackie Robinson in 1949.[18] Morgan earned five consecutive Gold Glove Awards at second base from 1973 to 1977, recognizing his superior fielding with a career .985 fielding percentage and 6,895 putouts over 22 seasons.[3] He was selected to ten All-Star Games, appearing in 1966, 1970, and every year from 1972 to 1979, often starting at second base for the National League.[3] In 1982, at age 38 with the San Francisco Giants, Morgan received the Silver Slugger Award for his offensive production as a designated hitter alternative, batting .275 with 19 home runs.[3] He also finished second in National League Rookie of the Year voting in 1965 after debuting with the Houston Colt .45s.[19] Among his statistical achievements, Morgan created the 200/500 club on August 27, 1978, by hitting his 200th career home run to join the 500 stolen bases milestone first in MLB history, a rare combination of power and speed later achieved only by Rickey Henderson, Paul Molitor, and Barry Bonds.[20]Career statistics and records

Joe Morgan played 22 seasons in Major League Baseball from 1963 to 1984, appearing in 2,649 games primarily as a second baseman.[3] His career batting line included a .271 batting average, .392 on-base percentage, .427 slugging percentage, and .819 OPS, with 2,517 hits, 268 home runs, 1,133 RBI, and 689 stolen bases in 9,277 at-bats.[3] Defensively, he posted a .982 fielding percentage at second base over 2,527 games, recording 7,511 putouts, 7,346 assists, 273 errors, and participation in 1,405 double plays.[3] | Season | G | AB | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BB | SO | BA | OBP | SLG | OPS | |--------|---|----|---|----|----|----|-----|----|----|----|----|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----| | Career | 2649 | 9277 | 2517 | 449 | 96 | 268 | 1133 | 689 | 1865 | 1015 | .271 | .392 | .427 | .819 |[3] Morgan's stolen base total ranked among the highest for second basemen, with league-leading marks of 67 in 1973 and 60 in 1976.[3] He also led the National League in walks four times: 115 in 1972, 111 in 1973, 132 in 1975, and 114 in 1976.[3] His 100.6 Wins Above Replacement (WAR) placed him fifth all-time among second basemen as of the latest rankings.[3]| Position | G | PO | A | E | DP | FPct |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2B | 2527 | 7511 | 7346 | 273 | 1405 | .982 |