Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

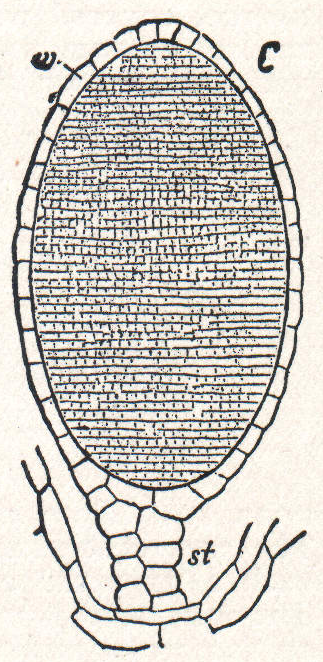

Antheridium

View on Wikipedia

An antheridium is a haploid structure or organ producing and containing male gametes (called antherozoids or sperm). The plural form is antheridia, and a structure containing one or more antheridia is called an androecium.[1][a]

Antheridia are present in the gametophyte phase of cryptogams like bryophytes and ferns.[2] Many algae and some fungi, for example, ascomycetes and water moulds, also have antheridia during their reproductive stages. In gymnosperms and angiosperms, the male gametophytes have been reduced to pollen grains, and in most of these, the antheridia have been reduced to a single generative cell within the pollen grain. During pollination, this generative cell divides and gives rise to sperm cells.

The female counterpart to the antheridium in cryptogams is the archegonium, and in flowering plants is the gynoecium.

An antheridium typically consists of sterile cells and spermatogenous tissue. The sterile cells may form a central support structure or surround the spermatogenous tissue as a protective jacket. The spermatogenous cells give rise to spermatids via mitotic cell division. In some bryophytes, the antheridium is borne on an antheridiophore, a stalk-like structure that carries the antheridium at its apex.[3]

Gallery

[edit]-

Magnified view of developing antheridia in Hypnum cupressiforme

-

"Moss flowers": each shoot has a cluster of antheridia, i.e., an androecium.

-

Sperm of the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha are produced on the upper surface of antheridiophores.

-

Cross-sectional micrograph of the antheridial head of Marchantia sp., showing antheridia containing spermatogenous tissue.

-

Antheridium (indicated by the red box) of an Equisetum sp.

See also

[edit]- Hornworts have antheridia, in some cases arranged within androecia.

- Microsporangia produce spores that give rise to male gametophytes.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The androecium is also the collective term for the stamens of flowering plants.

References

[edit]- ^ D. Christine Cargill; Karen S. Renzaglia; Juan Carlos Villarreal & R. Joel Duff (2005), "Generic concepts within hornworts: Historical review, contemporary insights and future directions", Australian Systematic Botany, 18: 7–16, doi:10.1071/sb04012

- ^ Voeller, Bruce (1971). "Developmental Physiology of Fern Gametophytes: Relevance for Biology". BioScience. 21 (6): 266–270. doi:10.2307/1295968. JSTOR 1295968.

- ^ Shimamura, Masaki (2016-02-01), "Marchantia polymorpha: Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Morphology of a Model System", Plant and Cell Physiology, 57 (2): 230–256, doi:10.1093/pcp/pcv192, ISSN 0032-0781, PMID 26657892

Further reading

[edit]- C.Michael Hogan. 2010. Fern. Encyclopedia of Earth. National council for Science and the Environment. Washington, DC