Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Anthozoa

View on Wikipedia

| Anthozoa Temporal range: Late Ediacaran to recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Coral outcrop on the Great Barrier Reef | |

| |

| Gorgonian with polyps expanded | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Subphylum: | Anthozoa Ehrenberg, 1834 |

| Classes | |

| |

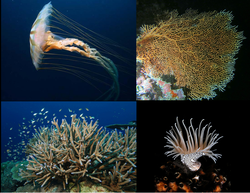

Anthozoa[1] is one of the three subphyla of Cnidaria, along with Medusozoa and Endocnidozoa.[2] It includes sessile marine invertebrates and invertebrates of brackish water, such as sea anemones, stony corals, soft corals and sea pens. Almost all adult anthozoans are attached to the seabed, while their larvae can disperse as plankton. The basic unit of the adult is the polyp, an individual animal consisting of a cylindrical column topped by a disc with a central mouth surrounded by tentacles. Sea anemones are mostly solitary, but the majority of corals are colonial, being formed by the budding of new polyps from an original, founding individual. Colonies of stony corals are strengthened by mainly aragonite and other materials, and can take various massive, plate-like, bushy or leafy forms.

Members of Anthozoa possess cnidocytes, a feature shared among other cnidarians such as the jellyfish, box jellies and parasitic Myxozoa and Polypodiozoa. The two classes of Anthozoa are class Hexacorallia, with members that have six-fold symmetry such as stony corals, sea anemones, tube anemones and zoanthids, and class Octocorallia, with members that have eight-fold symmetry, such as soft corals, gorgonians (sea pens, sea fans and sea whips), and sea pansies. Some additional species are also included as incertae sedis until their exact taxonomic position can be ascertained.

Anthozoans are carnivores, catching prey with their tentacles. Many species supplement their energy needs by making use of photosynthetic single-celled algae that live within their tissues. These species live in shallow water and many of them are hermatypic (reef-builders). Other species lack the zooxanthellae and, having no need for well-lit areas, typically live in deep-water locations.

Unlike other members of phylum Cnidaria, anthozoans do not have a medusa stage in their development. Instead, they release sperm and egg cells into the water. After fertilisation, the planula larvae form part of the plankton. When fully developed, the larvae settle on the seabed and attach to the substrate, undergoing metamorphosis into polyps. Some anthozoans can also reproduce asexually through budding or by breaking in pieces (fragmentation).

Diversity

[edit]

The name "Anthozoa" comes from the Greek words άνθος (ánthos; "flower") and ζώα (zóa; "animals"), hence ανθόζωα (anthozoa) = "flower animals", a reference to the floral appearance of their perennial polyp stage.[3]

Anthozoans live exclusively in marine and brackish water.[1] They include sea anemones, stony corals, soft corals, sea pens, sea fans and sea pansies. Anthozoa is the largest taxon of cnidarians; over six thousand solitary and colonial species have been described. They range in size from small individuals less than half a centimetre across to large colonies a metre or more in diameter. They include species with a wide range of colours and forms that build and enhance reef systems.[4][5] Although reefs and shallow water environments exhibit a great array of species, there are in fact more species of coral living in deep water than in shallow, and many taxa have shifted during their evolutionary history from shallow to deep water and vice versa.[6]

Phylogeny

[edit]In 1995, genetic studies by J. E. N. Veron and a group of scientists that analyzed the ribosomal DNA of many species, found that the order Ceriantipatharia, now deprecated and replaced by its constituent orders Ceriantharia and Antipatharia, [7][8] was "the most representative of the ancestral Anthozoa".[9]

After Ceriantipatharia became deprecated c. 2007, newer phylogenetic studies determined that Ceriantharia is not the basal clade of Anthozoa, but of Hexacorallia, and that Antipatharia and the remaining orders of Hexacorallia are its descendants.[10]

Anthozoa is a monophyletic clade within Cnidaria. A comprehensive phylogenetic study from 2021, has indicated that its two extant subclades, Hexacorallia and Octocorallia, are also monophyletic sisters.[10]

The same study has inferred the independent appearance of key characters in different lineages of subphylum Anthozoa. The reconstructed ancestor of Anthozoa is supposed to have been a solitary polyp with bilateral symmetry, lacking a skeleton and photosymbiosis, already present in the Tonian period (1000 to ~720 Mya) when the two classes of Anthozoa, Hexacorallia and Octocorallia, have probably diverged.[10]

Octocorallia gained colonial growth and calcified elements early on. The acquisition of photosymbiosis occurred many times independently in its different subclades.[10]

In the case of Hexacorallia, its early diverging order, Ceriantharia, retained the ancestral characteristics of being solitary, and lacking a skeleton and photosymbiosis. Zoantharia was the first order to gain colonial growth. Antipatharia and Scleractinia gained colonial growth independently from other orders. From the Devonian on, all subclades of Hexacorallia acquired photosymbiosis independently, with the exception of Ceriantharia and Relicanthus that lack it completely. A similar independent origin for radial symmetry happened to orders Actiniaria, Relicanthus, Scleractinia and Corallimorpharia.[10]

Cladogram of Anthozoa according to molecular phylogenetics

[edit]Molecular phylogenetics studies have determined that the most likely phylogeny of the extant clades of Anthozoa can be represented by the following cladogram: [10][11][12]

Taxonomy

[edit]The taxonomy of the subphylum Anthozoa is being continuously updated and modified, based on molecular biology, molecular phylogenetics, and other methods. Its most recent version can be found in the World Register of Marine Species.[1] It subdivides Anthozoa into two monophyletic, extant classes: Hexacorallia and Octocorallia, generally showing different symmetry of polyp structure, and two extinct, fossil classes: Rugosa † and Tabulata †.

Hexacorallia includes coral reef builders (Scleractinia, also called hermatypic stony corals), sea anemones (Actiniaria), and zoanthids (Zoantharia).

Octocorallia comprises the sea pens (Pennatulacea), soft corals (Octocorallia), and blue coral (Helioporacea). Sea whips and sea fans, known as gorgonians, are part of Alcyonacea and historically were divided into separate orders. [8]

Classification according to the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS)

[edit]†= extinct

- phylum Cnidaria

- subphylum Anthozoa

- class Hexacorallia

- order Actiniaria

- suborder Anenthemonae

- suborder Enthemonae

- suborder Helenmonae

- order Antipatharia

- order Ceriantharia

- order Corallimorpharia

- order Hexanthiniaria †

- order Kilbuchophyllida †

- order Scleractinia

- order Zoantharia

- order Actiniaria

- class Octocorallia

- order Malacalcyonacea

- order Scleralcyonacea

- class Rugosa †

- order Heterocorallia †

- order Pterocorallia †

- order Stauriida †

- order Stereolasmatina †

- class Tabulata †

- order Auloporida †

- order Favositida †

- order Halysitida †

- order Heliolitida †

- order Lichenariida †

- order Sarcinulida †

- order Syringoporida †

- order Tetradiida

- class Hexacorallia

- subphylum Anthozoa

Examples of some major anthozoan taxa

[edit]| Some major anthozoan taxa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Order | Image | Example | Characteristics | Distribution |

| Hexacorallia | Actiniaria Sea anemones |

|

Actinostola sp. | Mostly large, solitary polyps anchored to hard substrates. Often colourful. Zooxanthellate or azooxanthellate.[4] | Worldwide in shallow and deep water, with greatest diversity in tropics.[4] |

| Hexacorallia | Antipatharia Black coral |

|

Plumapathes pennacea | Bushy colonies with slender branches. Axial skeleton of dark-coloured thorny branches strengthened by a unique, non-collagen protein. Azooxanthellate.[4] | On vertical rock faces of reefs, or in deep water.[4] |

| Hexacorallia | Corallimorpharia Corallimorphs or coral anemones |

|

Discosoma sp. | Large, solitary polyps similar to sea anemones, but with stumpy columns and large oral discs with many short tentacles. Catch large prey and some species zooxanthellate.[4] | On coral reefs, mostly tropical.[4] |

| Hexacorallia | Rugosa Extinct |

|

Stereolasma rectum | Extinct order abundant in Middle Ordovician to Late Permian. Solitary or colonial, with a skeleton formed of calcite. Septa develop in multiples of four.[13] | Widespread. |

| Hexacorallia | Scleractinia Stony corals or hard corals |

|

Fungia fungites Tubastraea coccinea |

Solitary or colonial corals in a vast assortment of sizes and shapes, the stony skeleton being composed of aragonite. Septa develop in multiples of six.[13] Zooxanthellate or azooxanthellate.[4] | Shallow and deep water habitats worldwide, the greatest diversity being in tropical seas.[4] |

| Hexacorallia | Zoantharia Zoanthids |

|

"Dragon eye" coral Zoanthus sp. |

Small, mostly colonial species joined by coensarc or stolons. No hard skeleton but some incorporate solid matter into fleshy periderm.[4] | Mostly tropical, reef-dwelling species.[4] |

| Hexacorallia | Ceriantharia (suborder Penicillaria) Tube-dwelling anemones |

|

Arachnanthus sarsi | Solitary individuals with two rings of tentacles living in fibrous tubes in soft sediment. Distinguished from Spirularia by anatomy and cnidom.[14] | In soft sediment, worldwide.[15] |

| Hexacorallia | Ceriantharia (suborder Spirularia) Tube-dwelling anemones |

|

Cerianthus filiformis | Solitary individuals with two rings of tentacles living in fibrous tubes. Distinguished from Penicillaria by anatomy and cnidom.[14] | In soft sediment, worldwide.[15] |

| Octocorallia | Alcyonacea Soft corals and gorgonians |

|

Alcyonium digitatum Mushroom corals |

Colonial and diverse, with polyps almost completely embedded in thick fleshy coenosarc. Gorgonians have a horny skeleton. Zooxanthellate or azooxanthellate.[4] | Worldwide, mostly in tropical and subtropical waters, associated with coral reefs and in deep sea.[4] |

| Octocorallia | Helioporacea Blue corals |

|

Heliopora coerulea | Octocorals with a massive skeleton composed of aragonite secreted by underside of coenosarc. Zooxanthellate.[16] | Heliopora coerulea is IndoPacific; other species are from the Atlantic and Madagascar.[17] |

| Octocorallia | Pennatulacea Sea pens, sea feathers and sea pansies |

|

Ptilosarcus gurneyi | Colonial species taking pinnate, radial or club-like forms. Main axis is a single enlarged and elongated polyp. Has several types of specialist polyp. Azooxanthellate.[16] | Worldwide, from lower tidal to 6,000 m (20,000 ft)[18] |

Anatomy

[edit]The basic body form of an anthozoan is the polyp. This consists of a tubular column topped by a flattened area, the oral disc, with a central mouth; a whorl of tentacles surrounds the mouth. In solitary individuals, the base of the polyp is the foot or pedal disc, which adheres to the substrate, while in colonial polyps, the base links to other polyps in the colony.[4]

The mouth leads into a tubular pharynx which descends for some distance into the body before opening into the coelenteron, otherwise known as the gastrovascular cavity, that occupies the interior of the body. Internal tensions pull the mouth into a slit-shape, and the ends of the slit lead into two grooves in the pharynx wall called siphonoglyphs. The coelenteron is subdivided by a number of vertical partitions, known as mesenteries or septa. Some of these extend from the body wall as far as the pharynx and are known as "complete septa" while others do not extend so far and are "incomplete". The septa also attach to the oral and pedal discs.[4]

The body wall consists of an epidermal layer, a jellylike mesogloea layer and an inner gastrodermis; the septa are infoldings of the body wall and consist of a layer of mesogloea sandwiched between two layers of gastrodermis. In some taxa, sphincter muscles in the mesogloea close over the oral disc and act to keep the polyp fully retracted. The tentacles contain extensions of the coelenteron and have sheets of longitudinal muscles in their walls. The oral disc has radial muscles in the epidermis, but most of the muscles in the column are gastrodermal, and include strong retractor muscles beside the septa. The number and arrangement of the septa, as well as the arrangement of these retractor muscles, are important in anthozoan classification.[4]

The tentacles are armed with nematocysts, venom-containing cells which can be fired harpoon-fashion to snare and subdue prey. These need to be replaced after firing, a process that takes about forty-eight hours. Some sea anemones have a circle of acrorhagi outside the tentacles; these long projections are armed with nematocysts and act as weapons. Another form of weapon is the similarly armed acontia (threadlike defensive organs) which can be extruded through apertures in the column wall. Some stony corals employ nematocyst-laden "sweeper tentacles" as a defence against the intrusion of other individuals.[4]

Many anthozoans are colonial and consist of multiple polyps with a common origin joined by living material. The simplest arrangement is where a stolon runs along the substrate in a two dimensional lattice with polyps budding off at intervals. Alternatively, polyps may bud off from a sheet of living tissue, the coenosarc, which joins the polyps and anchors the colony to the substrate. The coenosarc may consist of a thin membrane from which the polyps project, as in most stony corals, or a thick fleshy mass in which the polyps are immersed apart from their oral discs, as in the soft corals.[4]

The skeleton of a stony coral in the order Scleractinia is secreted by the epidermis of the lower part of the polyp; this forms a corallite, a cup-shaped hollow made of calcium carbonate, in which the polyp sits. In colonial corals, following growth of the polyp by budding, new corallites are formed, with the surface of the skeleton being covered by a layer of coenosarc. These colonies adopt a range of massive, branching, leaf-like and encrusting forms.[19] Soft corals in the subclass Octocorallia are also colonial and have a skeleton formed of mesogloeal tissue, often reinforced with calcareous spicules or horny material, and some have rod-like supports internally.[20] Other anthozoans, such as sea anemones, are naked; these rely on a hydrostatic skeleton for support. Some of these species have a sticky epidermis to which sand grains and shell fragments adhere, and zoanthids incorporate these substances into their mesogloea.[4]

Biology

[edit]

Most anthozoans are opportunistic predators, catching prey which drifts within reach of their tentacles. The prey is secured with the help of sticky mucus, spirocysts (non-venomous harpoon cells) and nematocysts (venomous harpoon cells). The tentacles then bend to push larger prey into the mouth, while smaller, plankton-size prey, is moved by cilia to the tip of the tentacles which are then inserted into the mouth. The mouth can stretch to accommodate large items, and in some species, the lips may extend to help receive the prey. The pharynx then grasps the prey, which is mixed with mucus and slowly swallowed by peristalsis and ciliary action. When the food reaches the coelenteron, extracellular digestion is initiated by the discharge of the septa-based nematocysts and the release of enzymes. The partially digested food fragments are circulated in the coelenteron by cilia, and from here they are taken up by phagocytosis by the gastrodermal cells that line the cavity.[4]

Most anthozoans supplement their predation by incorporating into their tissues certain unicellular, photosynthetic organisms known as zooxanthellae (or zoochlorellae in a few instances); many fulfil the bulk of their nutritional requirements in this way. In this symbiotic relationship, the zooxanthellae benefit by using nitrogenous waste and carbon dioxide produced by the host while the cnidarian gains photosynthetic capability and increased production of calcium carbonate, a substance of great importance to stony corals.[21] The presence of zooxanthellae is not a permanent relationship. Under some circumstances, the symbionts can be expelled, and other species may later move in to take their place. The behaviour of the anthozoan can also be affected, with it choosing to settle in a well lit spot, and competing with its neighbours for light to allow photosynthesis to take place. Where an anthozoan lives in a cave or other dark location, the symbiont may be absent in a species that, in a sunlit location, normally benefits from one.[22] Anthozoans living at depths greater than 50 m (200 ft) are azooxanthellate because there is insufficient light for photosynthesis.[6]

With longitudinal, transverse and radial muscles, polyps are able to elongate and shorten, bend and twist, inflate and deflate, and extend and contract their tentacles. Most polyps extend to feed and contract when disturbed, often invaginating their oral discs and tentacles into the column. Contraction is achieved by pumping fluid out of the coelenteron, and reflation by drawing it in, a task performed by the siphonoglyphs in the pharynx which are lined with beating cilia. Most anthozoans adhere to the substrate with their pedal discs but some are able to detach themselves and move about, while others burrow into the sediment. Movement may be a passive drifting with the currents or in the case of sea anemones, may involve creeping along a surface on their base.[4]

Gas exchange and excretion is accomplished by diffusion through the tentacles and internal and external body wall, aided by the movement of fluid being wafted along these surfaces by cilia. The sensory system consists of simple nerve nets in the gastrodermis and epidermis, but there are no specialised sense organs.[4]

Anthozoans exhibit great powers of regeneration; lost parts swiftly regrow and the sea anemone Aiptasia pallida can be vivisected in the laboratory and then returned to the aquarium where it will heal. They are capable of a variety of asexual means of reproduction including fragmentation, longitudinal and transverse fission and budding.[4] Sea anemones for example can crawl across a surface leaving behind them detached pieces of the pedal disc which develop into new clonal individuals. Anthopleura species divide longitudinally, pulling themselves apart, resulting in groups of individuals with identical colouring and patterning.[23] Transverse fission is less common, but occurs in Anthopleura stellula and Gonactinia prolifera, with a rudimentary band of tentacles appearing on the column before the sea anemone tears itself apart.[24] Zoanthids are capable of budding off new individuals.[25]

Most anthozoans are unisexual but some stony corals are hermaphrodite. The germ cells originate in the endoderm and move to the gastrodermis where they differentiate. When mature, they are liberated into the coelenteron and thence to the open sea, with fertilisation being external.[4] To make fertilisation more likely, corals emit vast numbers of gametes, and many species synchronise their release in relation to the time of day and the phase of the moon.[26]

The zygote develops into a planula larva which swims by means of cilia and forms part of the plankton for a while before settling on the seabed and metamorphosing into a juvenile polyp. Some planulae contain yolky material and others incorporate zooxanthellae, and these adaptations enable these larvae to sustain themselves and disperse more widely.[4] The planulae of the stony coral Pocillopora damicornis, for example, have lipid-rich yolks and remain viable for as long as 100 days before needing to settle.[27]

Ecology

[edit]

Coral reefs are some of the most biodiverse habitats on earth, supporting large numbers of species of corals, fish, molluscs, worms, arthropods, starfish, sea urchins, other invertebrates and algae. Because of the photosynthetic requirements of the corals, they are found in shallow waters, and many of these fringe land masses.[28] With a three-dimensional structure, coral reefs are very productive ecosystems; they provide food for their inhabitants, hiding places of various sizes to suit many organisms, perching places, barriers to large predators and solid structures on which to grow. They are used as breeding grounds and as nurseries by many species of pelagic fish, and they influence the productivity of the ocean for miles around.[29] Anthozoans prey on animals smaller than they are and are themselves eaten by such animals as fish, crabs, barnacles, snails and starfish. Their habitats are easily disturbed by outside factors which unbalance the ecosystem. In 1989, the invasive crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) caused havoc in American Samoa, killing 90% of the corals in the reefs.[30]

Corals that grow on reefs are called hermatypic, with those growing elsewhere are known as ahermatypic. Most of the latter are azooxanthellate and live in both shallow and deep sea habitats. In the deep sea they share the ecosystem with soft corals, polychaete worms, other worms, crustaceans, molluscs and sponges. In the Atlantic Ocean, the cold-water coral Lophelia pertusa forms extensive deep-water reefs which support many other species.[31]

Other fauna, such as hydrozoa, bryozoa and brittle stars, often dwell among the branches of gorgonian and coral colonies.[32] The pygmy seahorse not only makes certain species of gorgonians its home, but closely resembles its host and is thus well camouflaged.[33] Some organisms have an obligate relationship with their host species. The mollusc Simnialena marferula is only found on the sea whip Leptogorgia virgulata, is coloured like it and has sequestered its defensive chemicals, and the nudibranch Tritonia wellsi is another obligate symbiont, its feathery gills resembling the tentacles of the polyps.[34]

A number of sea anemone species are commensal with other organisms. Certain crabs and hermit crabs seek out sea anemones and place them on their shells for protection, and fish, shrimps and crabs live among the anemone's tentacles, gaining protection by being in close proximity to the stinging cells. Some amphipods live inside the coelenteron of the sea anemone.[35] Despite their venomous cells, sea anemones are eaten by fish, starfish, worms, sea spiders and molluscs. The sea slug Aeolidia papillosa feeds on the aggregating anemone (Anthopleura elegantissima), accumulating the nematocysts for its own protection.[35]

Paleontology

[edit]Several extinct orders of corals from the Paleozoic era (~540–252 million years ago) are thought to be close to the ancestors of modern Scleractinia:[36][37]

- Numidiaphyllida †

- Kilbuchophyllida †

- Rugosa †

- Tabulata †

- Cothoniida †

- Tabuloconida †

These are all corals and correspond to the fossil record time line. With readily-preserved hard calcareous skeletons, they comprise the majority of Anthozoan fossils.

| |

|

Timeline of the major coral fossil record and developments from 650 m.y.a. to present.[38][39] |

|

Interactions with humans

[edit]Coral reefs and shallow marine environments are threatened, not only by natural events and increased sea temperatures, but also by such man-made problems as pollution, sedimentation and destructive fishing practices. Pollution may be the result of run-off from the land of sewage, agricultural products, fuel or chemicals. These may directly kill or injure marine life, or may encourage the growth of algae that smother native species, or form algal blooms with wide-ranging effects. Oil spills at sea can contaminate reefs, and also affect the eggs and larva of marine life drifting near the surface.[40]

Corals are collected for the aquarium trade, and this may be done with little care for the long-term survival of the reef. Fishing among reefs is difficult and trawling does much mechanical damage. In some parts of the world explosives are used to dislodge fish from reefs, and cyanide may be used for the same purpose; both practices not only kill reef inhabitants indiscriminately but also kill or damage the corals, sometimes stressing them so much that they expel their zooxanthellae and become bleached.[40]

Deep water coral habitats are also threatened by human activities, particularly by indiscriminate trawling. These ecosystems have been little studied, but in the perpetual darkness and cold temperatures, animals grow and mature slowly and there are relatively fewer fish worth catching than in the sunlit waters above. To what extent deep-water coral reefs provide a safe nursery area for juvenile fish has not been established, but they may be important for many cold-water species.[41]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Hoeksema, Bert (2024-02-29). "Anthozoa. Ehrenberg, 1834". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2025-05-16.

- ^ WoRMS (2025). "Cnidaria". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2025-03-25.

- ^ "Anthozoa: Etymology". Fine Dictionary. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard, S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 112–148. ISBN 978-81-315-0104-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crowther, Andrea L. (2011). Z.-Q. Zhang (ed.). "Class Anthozoa Ehrenberg, 1834. In: Zhang, Z.-Q. (Ed.) Animal biodiversity: An outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3148 (1): 19–23. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.5.

- ^ a b Woodley, Cheryl M.; Downs, Craig A.; Bruckner, Andrew W.; Porter, James W.; Galloway, Sylvia B. (2016). Diseases of Coral. John Wiley & Sons. p. 416. ISBN 978-0-8138-2411-6.

- ^ WoRMS (2025). "Ceriantipatharia". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2025-03-25.

- ^ a b Daly, M.; Brugler, M.P.; Cartwright, P.; Collins, A.G.; Dawson, M.N.; Fautin, D.G.; France, S.C.; McFadden, C.S.; Opresko, D.M.; Rogriguez, E.; Romano, S.L.; Stake, J.L. (2007). "The phylum Cnidaria: A review of phylogenetic patterns and diversity 300 years after Linnaeus" (PDF). Zootaxa. 1668: 1–766. doi:10.5281/zenodo.180149.

- ^ Chen, C. A.; D. M. Odorico; M. ten Lohuis; J. E. N. Veron; D. J. Miller (June 1995). "Systematic relationships within the Anthozoa (Cnidaria: Anthozoa) using the 5'-end of the 28S rDNA". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 4 (2): 175–183. Bibcode:1995MolPE...4..175C. doi:10.1006/mpev.1995.1017. PMID 7663762.

- ^ a b c d e f McFadden, Catherine S.; Quattrini, Andrea M.; Brugler, Mercer R.; Cowman, Peter F.; Dueñas, Luisa F.; Kitahara, Marcelo V.; Paz-García, David A.; Reimer, James D.; Rodríguez, Estefanía (2021). "Phylogenomics, Origin, and Diversification of Anthozoans (Phylum Cnidaria)". Systematic Biology. 70 (4): 635–647. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syaa103. PMID 33507310.

- ^ McFadden, C.S.; van Ofwegen, L.P.; Quattrini, A.M. (2022) (2025). "Malacalcyonacea". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2025-03-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species - Scleralcyonacea". marinespecies.org. Retrieved 2024-07-14.

- ^ a b Taylor, Paul D.; Lewis, David N. (2007). Fossil Invertebrates. Harvard University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-674-02574-5.

- ^ a b Goffredo, Stefano; Dubinsky, Zvy (2016). The Cnidaria, Past, Present and Future: The world of Medusa and her sisters. Springer International Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 978-3-319-31305-4.

- ^ a b Fautin, Daphne G.; Westfall, Jane A.; Cartwright, Paulyn; Daly, Marymegan; Wyttenbach, Charles R. (2007). Coelenterate Biology 2003: Trends in Research on Cnidaria and Ctenophora. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-4020-2762-8.

- ^ a b Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Holt-Saunders International. pp. 168–169. ISBN 978-0-03-056747-6.

- ^ Fabricius, Katharina; Alderslade, Philip (2001). Soft Corals and Sea Fans: A Comprehensive Guide to the Tropical Shallow Water Genera of the Central-West Pacific, the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Australian Institute of Marine Science. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-642-32210-4.

- ^ Williams, G.C. (2011). "The global diversity of sea pens (Cnidaria: Octocorallia: Pennatulacea)". PLOS ONE. 6 (7) e22747. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622747W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022747. PMC 3146507. PMID 21829500.

- ^ "Corals: How do stony corals grow? What forms do they take?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ "Introduction to the Octocorallia". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ "Contribution to the BUFUS Newsletter, Field excursion to Milne Bay Province - Papua New Guinea, Madl and Yip 2000". Archived from the original on 2020-05-11. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ^ Light, Sol Felty (2007). The Light and Smith Manual: Intertidal Invertebrates from Central California to Oregon. University of California Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-520-23939-5.

- ^ Geller, Jonathan B.; Fitzgerald, Laurie J.; King, Chad E. (2005). "Fission in Sea Anemones: Integrative Studies of Life Cycle Evolution1". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 45 (4): 615–622. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.315.4480. doi:10.1093/icb/45.4.615. PMID 21676808.

- ^ Goffredo, Stefano; Dubinsky, Zvy, eds. (2016). The Cnidaria, Past, Present and Future: The world of Medusa and her sisters. Springer International Publishing. p. 240. ISBN 978-3-319-31305-4.

- ^ Carefoot, Tom. "Learn about Sea Anemones and Relatives: Reproduction: Asexual". A Snail's Odyssey. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ "Corals: How do corals reproduce?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 25 March 2008. Archived from the original on February 24, 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ Richmond, R. H. (1987). "Energetics, competency, and long-distance dispersal of planula larvae of the coral Pocillopora damicornis". Marine Biology. 93 (4): 527–533. Bibcode:1987MarBi..93..527R. doi:10.1007/BF00392790. S2CID 84571244.

- ^ "Corals: Importance of coral reefs". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ Sorokin, Yuri I. (2013). Coral Reef Ecology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-3-642-80046-7.

- ^ "Corals: Natural Threats to Coral Reefs". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ Roberts, J. Murray (2009). Cold-Water Corals: The Biology and Geology of Deep-Sea Coral Habitats. Cambridge University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-521-88485-3.

- ^ Haywood, Martyn; Sue Wells (1989). The Manual of Marine Invertebrates. Tetra Press:Salamander Books Ltd. p. 208. ISBN 978-3-89356-033-2.

- ^ Agbayani, Eli. "Hippocampus bargibanti, Pygmy seahorse". FishBase. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Ruppert, Edward E.; Richard S. Fox (1988). Seashore animals of the Southeast: a guide to common shallow-water invertebrates of the Southeastern Atlantic Coast. University of South Carolina Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-87249-535-7.

- ^ a b Van-Praët, M. (1985). Advances in Marine Biology. Academic Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-08-057945-0.

- ^ Oliver, William A. Jr. (October 1996). "Origins and relationships of Paleozoic coral groups and the origin of the Scleractinia". The Paleontological Society Papers. 1 (Paleobiology and Biology of Corals): 107–134. doi:10.1017/S1089332600000073. Retrieved 2025-04-30.

- ^ Kotrc, Ben (2005). "Anthozoa: Subgroups". Fossil Groups. University of Bristol. Archived from the original on 2009-09-27. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ^ Waggoner, Ben M. (2000). Smith, David; Collins, Allen (eds.). "Anthozoa: Fossil Record". Anthozoa. UCMP. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Oliver, William A. Jr. (2003). "Corals: Table 1". Fossil Groups. USGS. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Corals: Anthropogenic threats to corals". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ Roberts, J. Murray (2009). Cold-Water Corals: The Biology and Geology of Deep-Sea Coral Habitats. Cambridge University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-521-88485-3.

External links

[edit]Anthozoa

View on GrokipediaSystematics and Phylogeny

Phylogenetic Relationships

Anthozoa constitutes a monophyletic class within the phylum Cnidaria, sister to the clade Medusozoa, which encompasses taxa capable of producing medusae such as Hydrozoa, Scyphozoa, Cubozoa, and Staurozoa.[7] This positioning aligns with the anthozoan life cycle lacking a free-swimming medusa stage, contrasting with medusozoans, and is corroborated by ribosomal RNA and mitogenomic analyses despite occasional discrepancies in early mitochondrial datasets attributed to substitution saturation.[8] Recent phylogenomic studies using hundreds of loci further affirm the monophyly of Anthozoa and its distinction from Medusozoa, resolving prior ambiguities through expanded taxon sampling and nuclear gene data.[9] Internally, Anthozoa divides into two reciprocally monophyletic subclasses: Hexacorallia and Octocorallia, differentiated by mesenterial arrangements and tentacle symmetries—six-partite in Hexacorallia and eight-partite in Octocorallia.[10] Hexacorallia includes orders such as Scleractinia (stony corals), Actiniaria (sea anemones), Antipatharia (black corals), and Zoantharia, with Ceriantharia emerging as the earliest diverging lineage among hexacorals based on phylogenomic reconstructions.[9] Octocorallia encompasses orders like Alcyonacea (soft corals), Helioporacea (blue corals), and Pennatulacea (sea pens), whose monophyly is robustly supported by mitochondrial and nuclear markers, though familial relationships within it continue to refine with increased genomic data.[11] Disagreements in earlier mitogenomic phylogenies, which sometimes implied anthozoan paraphyly by nesting medusozoans within, have been reconciled by demonstrating that nuclear datasets exhibit lower saturation and better resolve deep cnidarian divergences, prioritizing comprehensive phylogenomics over lineage-specific mitochondrial biases.[12] These findings underscore Anthozoa's basal role in Cnidaria evolution, with fossil evidence from Ediacaran-like forms potentially linking to crown-group anthozoans around 540 million years ago, though molecular clocks suggest diversification post-Cambrian explosion.[13]Taxonomic Classification

Anthozoa constitutes a major lineage within the phylum Cnidaria, encompassing organisms such as sea anemones, stony and soft corals, black corals, and sea pens, with over 7,500 described species. Traditionally ranked as a class, contemporary systematic frameworks, informed by molecular phylogenetics and morphological traits like tentacle arrangement and mesentery configuration, elevate its position to subphylum under Cnidaria, containing two primary classes: Hexacorallia and Octocorallia.[14][15] This division is based on Hexacorallia's six- or multiple-of-six-fold symmetry versus Octocorallia's eight-fold symmetry, with the former typically featuring solid calcium carbonate skeletons in some orders and the latter producing sclerites.[16] Some classifications, such as NCBI Taxonomy, additionally recognize Ceriantharia (tube anemones) as a separate subclass or basal lineage within Anthozoa, reflecting unresolved phylogenetic placement from ribosomal DNA analyses.[17]| Class | Major Orders | Characteristic Features and Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Hexacorallia | Actiniaria, Antipatharia, Corallimorpharia, Scleractinia, Zoantharia | Polyps with unbranched tentacles in multiples of six; includes sea anemones (Actiniaria), black corals (Antipatharia), mushroom corals and zoanthids (Zoantharia), and reef-building stony corals (Scleractinia with aragonite skeletons).[18][17] |

| Octocorallia | Alcyonacea, Helioporacea, Pennatulacea | Polyps with eight pinnate tentacles; includes soft corals and gorgonians (Alcyonacea with proteinaceous or sclerite-based axes), blue corals (Helioporacea with hydrozoan-like calcite skeletons), and colonial sea pens (Pennatulacea).[19][17] |