Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

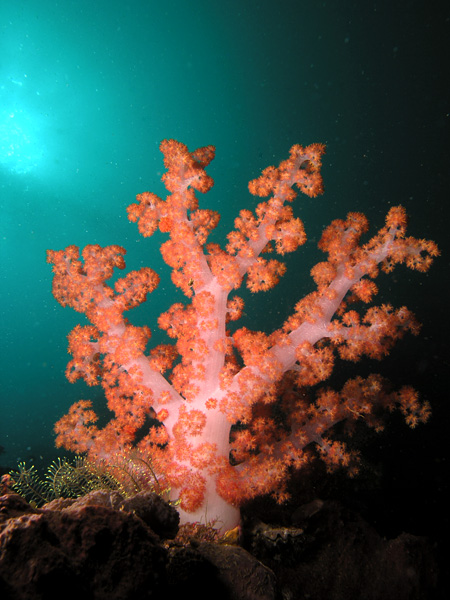

Octocorallia

View on Wikipedia

| Octocorallia Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Dendronephthya klunzingeri | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Subphylum: | Anthozoa |

| Class: | Octocorallia Haeckel, 1866 |

| Orders | |

| |

Octocorallia, along with Hexacorallia, is one of the two extant classes of Anthozoa.[1] It comprises over 3,000 species of marine and brackish animals consisting of colonial polyps with 8-fold symmetry, commonly referred to informally as "soft corals". It was previously known by the now unaccepted scientific names Alcyonacea[2] and Gorgonacea,[3] both deprecated c. 2022, and by the also deprecated name of Alcyonaria, in earlier times.[4][5]

Its only two orders are Malacalcyonacea and Scleralcyonacea, which include corals such as those under the common names of blue corals, sea pens, and gorgonians (sea fans and sea whips).[4] These animals have an internal skeleton secreted by their mesoglea, and polyps with typically eight tentacles and eight mesenteries. As is the case with all cnidarians, their complex life cycle includes a motile, planktonic phase (a larva called planula), and a later characteristic sessile phase.

Octocorals have existed at least since the Ordovician period, as shown by Maurits Lindström's findings in the 1970s.[6] A 2023 work suggested that the Cambrian fossil Pywackia may represent a Cambrian octocoral,[7][8][9] and molecular techniques have even pointed to a Precambrian origin for Octocorallia. For instance, a 2021 study built a time-calibrated phylogenetic tree that has placed the origin of Octocorallia in the Ediacaran (578 Mya).[10]

Biology

[edit]

Octocorals resemble the stony corals in general appearance and in the size of their polyps, but lack the distinctive stony skeleton. Also unlike the stony corals, each polyp has only eight tentacles, each of which is feather-like in shape, with numerous side-branches, or pinnules.

Octocorals are colonial organisms, with numerous tiny polyps embedded in a soft matrix that forms the visible structure of the colony. The matrix is composed of mesogleal tissue, lined by a continuous epidermis and perforated by numerous tiny channels. The channels interconnect the gastrovascular cavities of the polyps, allowing water and nutrients to flow freely between all the members of the colony. The skeletal material, called coenenchyme, is composed of living tissue secreted by numerous wandering amoebocytes. Although it is generally soft, in many species it is reinforced with calcareous or horny material.[11]

The polyp is largely embedded within the colonial skeleton, with only the uppermost surface, including the tentacles and mouth, projecting about the surface. The mouth is slit-like, with a single ciliated groove, or siphonoglyph, at one side to help control water flow. It opens into a tubular pharynx that projects down into a gastrovascular cavity that occupies the hollow interior. The pharynx is surrounded by eight radial partitions, or mesenteries, that divide the upper part of the gastrovascular cavity into chambers, one of which connects to the hollow space inside each tentacle. The gonads are located near the base of each mesentery.[11] Octocorals have high phenotypic plasticity from adapting to dynamic environments where temperature, pH, and other parameters are in constant flux[12] and have shown high recruitment rates post-die-off events caused by El Niño events.[13]

Bioluminescence is found in 32 genera, a trait estimated to have evolved 540 million years ago, the earliest timing of emergence of bioluminescence in the marine environment.[14]

Phylogeny

[edit]Octocorallia is considered to be monophyletic, meaning that all contained species are descended from a common ancestor, but the relationships between subdivisions are not well known. The sea pens (Pennatulacea) and blue coral (Helioporacea) continue to be assigned separate orders, whereas the current order Alcyonacea was historically represented by four orders: Alcyonacea, Gorgonacea, Stolonifera and Telestacea.

Unplaced taxa

[edit]The following taxa are unplaced within Octocorallia according to the World Register of Marine Species as of April 2024[update]:[15]

Families:

- Haimeidae Wright, 1865

- Pseudogorgiidae Utinomi & Harada, 1973

Genera:

- Aspera Dautova, 2018

- Bayergorgia Williams & López-González, 2005

- Briareopsis Bayer, 1993

- Caliacis Deichmann, 1936

- Canarya Ocaña & van Ofwegen, 2003

- Ceratocaulon Jungersen, 1892

- Chalcogorgia Bayer, 1949

- Chondronephthya Utinomi, 1960

- Daniela von Koch, 1891

- Denhartogia Ocaña & van Ofwegen, 2003

- Distichogorgia Bayer, 1979

- Elasmogorgia Wright & Studer, 1889

- Flagelligorgia Cairns & Cordeiro, 2017

- Hypnogorgia Duchassaing & Michelotti, 1864

- Inflatocalyx Verseveldt & Bayer, 1988

- Lanthanocephalus Williams & Starmer, 2000

- Lignopsis Pérez & Zamponi, 2000

- Mesogligorgia López-González, 2007

- Moolabalia Alderslade, 2001

- Pseudocladochonus Versluys, 1907

- Pseudosuberia Kükenthal, 1916

- Pseudothesea Kükenthal, 1919

- Rhipiopathes

- Rolandia de Lacaze-Duthiers, 1900

- Scleranthelia Studer, 1878

- Speirogorgia Williams, 2019

- Sphaeralcyon López-González & Gili, 2000

- Stereacanthia Thomson & Henderson, 1906

- Stereogorgia Kükenthal, 1916

- Stereosoma Hickson, 1894

- Tesseranthelia Bayer, 1981

- Thelogorgia Bayer, 1991

- Tubigorgia Pasternak, 1985

- Verseveldtia Williams, 1990

- Williamsium Moore, Alderslade & Miller, 2017

- Xenogorgia Bayer & Muzik, 1976

References

[edit]- ^ Hoeksema, Bert (29 February 2024). "Octocorallia. Haeckel, 1866". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ McFadden, Cathy (2 November 2022). "Alcyonacea. Lamouroux, 1812". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ McFadden, Cathy (6 November 2022). "Gorgonacea. Lamouroux, 1816". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 16 May 2025.

- ^ a b Daly, M.; Brugler, M.P.; Cartwright, P.; Collins, A.G.; Dawson, M.N.; Fautin, D.G.; France, S.C.; McFadden, C.S.; Opresko, D.M.; Rogriguez, E.; Romano, S.L.; Stake, J.L. (21 December 2007). "The phylum Cnidaria: A review of phylogenetic patterns and diversity 300 years after Linnaeus". Zootaxa. 1668: 1–766. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.1668.1.11. hdl:1808/13641.

- ^ Fabricius, Katharina (2011). "Octocorallia". Encyclopedia of Modern Coral Reefs. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. pp. 740–745. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2639-2_35. ISBN 978-90-481-2638-5.

- ^ Bergström, Stig M.; Bergström, Jan; Kumpulainen, Risto; Ormö, Jens; Sturkell, Erik (2007). "Maurits Lindström – A renaissance geoscientist". GFF. 129 (2): 65–70. Bibcode:2007GFF...129...65B. doi:10.1080/11035890701292065. S2CID 140593975.

- ^ Taylor, Paul D.; Berning, Björn; Wilson, Mark A. (November 2013). "Reinterpretation of the Cambrian 'bryozoan' Pywackia as an octocoral". Journal of Paleontology. 87 (6): 984–990. Bibcode:2013JPal...87..984T. doi:10.1666/13-029. ISSN 0022-3360. S2CID 129113026.

- ^ Landing, Ed; Antcliffe, Jonathan B.; Brasier, Martin D.; English, Adam B. (2015). "Distinguishing Earth's oldest known bryozoan (Pywackia, late Cambrian) from pennatulacean octocorals (Mesozoic–Recent)". Journal of Paleontology. 89 (2): 292–317. Bibcode:2015JPal...89..292L. doi:10.1017/jpa.2014.26.

- ^ Hageman, Steven J.; Vinn, Olev (2023). "Late Cambrian Pywackia is a cnidarian, not a bryozoan: Insights from skeletal microstructure". Journal of Paleontology. 97 (5): 990–1001. Bibcode:2023JPal...97..990H. doi:10.1017/jpa.2023.35.

- ^ McFadden, Catherine S.; Quattrini, Andrea M.; Brugler, Mercer R.; Cowman, Peter F.; Dueñas, Luisa F.; Kitahara, Marcelo V.; Paz-García, David A.; Reimer, James D.; Rodríguez, Estefanía (2021). "Phylogenomics, Origin, and Diversification of Anthozoans (Phylum Cnidaria)". Systematic Biology. 70 (4): 635–647. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syaa103. PMID 33507310.

- ^ a b Barnes, Robert D. (1982). Invertebrate Zoology. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 164–169. ISBN 0-03-056747-5.

- ^ Lopes, Ana Rita; Faleiro, Filipa; Rosa, Inês C.; Pimentel, Marta S.; Trubenbach, Katja; Repolho, Tiago; Diniz, Mário; Rosa, Rui (11 June 2018). "Physiological resilience of a temperate soft coral to ocean warming and acidification". Cell Stress and Chaperones. 23 (5): 1093–1100. doi:10.1007/s12192-018-0919-9. ISSN 1355-8145. PMC 6111073. PMID 29948929.

- ^ Lasker, H. R.; Martínez-Quintana, Á.; Bramanti, L.; Edmunds, P. J. (9 March 2020). "Resilience of Octocoral Forests to Catastrophic Storms". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 4286. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.4286L. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61238-1. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7063042. PMID 32152448.

- ^ Deleo, Danielle M.; Bessho-Uehara, Manabu; Haddock, Steven H.D.; McFadden, Catherine S.; Quattrini, Andrea M. (2024). "Evolution of bioluminescence in Anthozoa with emphasis on Octocorallia". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 291 (2021). doi:10.1098/rspb.2023.2626. PMC 11040251. PMID 38654652.

- ^ "Octocorallia incertae sedis". WoRMS. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 23 April 2024.