Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

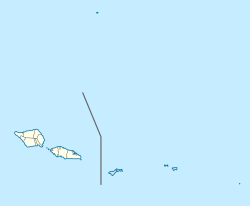

Apia (Samoan: [a.pi.a]) is the capital and largest city of Samoa. It is located on the central north coast of Upolu, Samoa's second-largest island. Apia falls within the political district (itūmālō) of Tuamasaga.

Key Information

The Apia Urban Area (generally known as the City of Apia) has a population of 35,974 (2021 census).[2] Its geographic boundaries extend from the east approximately from Letogo village in Vaimauga to the west in the newer, industrialized region of Apia which extends to Vaitele village in Faleata.

History

[edit]

Apia was originally a small village (the 1800 population was 304[2]), from which the country's capital took its name. Apia Village still exists within the larger modern capital of Apia, which has grown into a sprawling urban area that encompasses many villages. Like every other settlement in the country, Apia Village has its own matai (leaders) and fa'alupega (genealogy and customary greetings) according to fa'a Samoa.[citation needed]

The modern city of Apia was founded in the 1850s, and it has been the official capital of Samoa since 1959.[3] Seumanutafa Pogai was high chief until his death in 1898.

The harbour was the site of a notorious 15 March 1889 naval standoff in which seven ships — from Germany, the US, and Britain — refused to leave the harbour, even though a typhoon was clearly approaching, lest the first one to move lose face. All the ships sank or were damaged beyond repair, except for the British cruiser Calliope, which managed to leave port, travelling at a rate of one mile per hour, and was able to ride out the storm. Nearly 200 American and German people died.[4]

Western Samoa was ruled by Germany as German Samoa from 1900 to 1914, with Apia as its capital.[citation needed] In August 1914, the Occupation of German Samoa by an expeditionary force from New Zealand began. New Zealand governed the islands, (as the Western Samoa Trust Territory) from 1920 until Samoan independence in 1962 – first under a League of Nations Class C Mandate and then, after 1945, as a United Nations Trust Territory.[5]

The country underwent a struggle for political independence in the early 1900s, organised under the aegis of the national Mau movement. During this period, the streets of Apia were the site of non-violent protests and marches, in the course of which many Samoans were arrested. On what became known as "Black Saturday" (28 December 1929), during a peaceful Mau gathering in the town, the New Zealand constabulary killed the paramount chief Tupua Tamasese Lealofi III.[6]

During World War II the United States Navy built and operated Naval Base Upolu from 1941 to 1944.[7][8]

Geography

[edit]

Apia is situated on a natural harbour at the mouth of the Vaisigano River. It is on a narrow coastal plain with Mount Vaea (elevation 472 metres (1,549 ft)), the burial place of writer Robert Louis Stevenson, directly to its south. Two main ridges run south on either side of the Vaisigano River, with roads on each. The more western of these is Cross Island Road, one of the few roads cutting north to south across the middle of the island to the south coast of Upolu.[citation needed]

Climate

[edit]Apia features a tropical rainforest climate (Af according to the Köppen climate classification) with consistent temperatures throughout the year. Nevertheless, the climate is not equatorial because the trade winds are the dominant aerological mechanism and besides there are a few cyclones. Apia's driest months are July and August when on average about 80 millimetres (3.1 in) of rain falls. Its wettest months are December through March when average monthly precipitation easily exceeds 300 millimetres (12 in). Apia's average temperature for the year is 26 °C (79 °F). Apia averages roughly 3,000 millimetres (120 in) of rainfall annually.

| Climate data for Apia (Elevation: 2 m or 6.6 ft) (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1971–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.2 (97.2) |

34.6 (94.3) |

35.2 (95.4) |

36 (97) |

37.6 (99.7) |

34.7 (94.5) |

33.7 (92.7) |

35.9 (96.6) |

35.3 (95.5) |

34.8 (94.6) |

34.9 (94.8) |

35.1 (95.2) |

37.6 (99.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.6 (87.1) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.9 (87.6) |

31.1 (88.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.8 (85.6) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30 (86) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.4 (86.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.6 (81.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27 (81) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24.5 (76.1) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24 (75) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.9 (75.0) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.1 (75.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.6 (63.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 482.8 (19.01) |

406.3 (16.00) |

302 (11.9) |

231.8 (9.13) |

244.6 (9.63) |

139.2 (5.48) |

132.8 (5.23) |

112.3 (4.42) |

143.3 (5.64) |

220.7 (8.69) |

260.5 (10.26) |

413.7 (16.29) |

3,090 (121.68) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 20.5 | 18.4 | 18.1 | 13.9 | 13.2 | 10.1 | 10.7 | 9.9 | 12 | 13.1 | 15.5 | 17.8 | 173.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 149 | 160 | 173 | 186 | 193 | 197 | 213 | 219 | 207 | 199 | 181 | 154 | 2,230 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[9] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Bank (sunshine 1971–2000)[10] | |||||||||||||

Administration

[edit]

Apia is part of the Tuamasaga political district and of election district Vaimauga 1,2,3,4 and Faleata 1,2, and 3. There is no city administration for Apia, as it consists of some 45 individual, independent traditional and freehold villages. Apia proper is just a small village between the mouths of the Vaisigano (east) and Mulivai (west) rivers, and is framed by Matautu and Vaiala traditional villages. Together with several freehold villages (no traditional village council), these 45 villages constitute "Downtown Apia".

The Planning and Urban Management Act 2004[11] was passed by parliament to better plan for the urban growth of Samoa's built-up areas, with particular reference to the future urban management of Apia. The city's historical haphazard growth from village to colonial trading post to the major financial and business centre of the country has resulted in major infrastructural problems in the city. Problems of flooding are commonplace in the wet season, given the low flood-prone valley that the city is built on. In the inner-city village of Sogi, there are major shoreline pollution and effluent issues given that the village is situated on swamplands. The disparate village administrations of the Apia Urban Area has resulted in a lack of a unified and codified legislative approach to sewage disposal. The significant increase in vehicle ownership has resulted in traffic congestion in the inner city streets and the need for major projects in road-widening and traffic management. The PUMA legislation sets up the Planning Urban Management Authority to manage better the unique planning issues facing Apia's urban growth.

City features

[edit]

Mulinuʻu, the old ceremonial capital, lies at the city's western end, and is the location of the Parliament House (Maota Fono), and the historic observatory built during the German era is now the meteorology office.

The historic Catholic cathedral in Apia, the Immaculate Conception of Mary Cathedral, was dedicated 31 December 1867. It was pulled down mid-2011, reportedly due to structural damage from the earthquake of September 2009. A new cathedral was built and dedicated 31 May 2014.

An area of reclaimed land jutting into the harbour is the site of the Fiame Mataafa Faumuina Mulinuu II (FMFM II) building, the multi-storey government offices named after the first Prime Minister of Samoa, and the Central Bank of Samoa. A clock tower erected as a war memorial acts as a central point for the city. The new market (maketi fou) is inland at Fugalei, where it is more protected from the effects of cyclones. Apia still has some of the early, wooden, colonial buildings which remain scattered around the town, most notably the old courthouse from the German colonial era, with a museum on the upper floor (the new courthouse is in Mulinuʻu). Recent infrastructural development and economic growth has seen several multi-storey buildings rise in the city. The ACC building (2001) houses the Accident Compensation Board, the National Bank of Samoa, and some government departments. The mall below it is home to shops and eateries. The Samoatel building (2004) which is the site for Samoa's international telecommunications hub, was built inland at Maluafou, also to protect it from the effects of seasonal cyclones. The DBS building (2007) in Savalalo houses the Development Bank of Samoa and new courts complex in Mulinuu, with the district, supreme, and land & titles courts (2010). The Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Building (2012) in Sogi houses government ministries. Another addition to Apia's skyline is the SNPF Molesi shopping mall, opened in 2013. A new hospital complex was completed at Mot'ootua.

Scottish-born writer Robert Louis Stevenson spent the last four years of his life here, and is buried on Mount Vaea, overlooking both the city and the home he built, Vailima, now a museum in his honour. Stevenson had taken the Samoan name Tusitala ("writer of tales").[12]

Falemata'aga - Museum of Samoa is located in a former German colonial school in the city.[13]

The Bahá’í House of Worship for the Pacific is located in Apia, one of only eight continental Bahá’í Houses of Worship. Designed by architect Hossein Amanat and opened in 1984, it serves the island as a gathering space for people of all backgrounds and religions to meditate, reflect, and pray together.[14]

Economy

[edit]Talofa Airways and Samoa Airways have their headquarters in Apia.[15] Grey Investment Group has its headquarters in downtown Apia. This company also owned the first private National Bank of Samoa in Samoa, with Grey Investment Group, Samoa Artisan Water Company Ltd and Apia Bottling Company Ltd as shareholders. Grey Investment owns a multitude of commercial and residential property investments throughout Samoa and New Zealand.

Thirty per cent of the businesses in downtown Apia are owned by one Chinese family. Ten per cent of the downtown businesses are owned by Europeans, while the other 60% are owned by the local community.

Transport

[edit]

Apia Harbour is by far the largest and busiest harbour in Samoa. International shipping with containers, LPG gas, and fuels all dock here. Ferries to Tokelau and American Samoa depart from here.

Apia is served by a good road network, which is generally kept reasonably well maintained. Most of the main roads are sealed; the unsealed roads have lower use. Vehicles drive on the left-hand side of the road since 7 September 2009.[16]

The Samoan government started the second phase of a major upgrading of arterial routes around the Apia Urban Area in 2012, with incremental widening of major roads around the city.[17]

The country has no trains or trams, but is served by an extensive, privatised bus and taxi system. People commonly walk around the town, or even some distances outside it. There are few bicycles and motorcycles, but traffic congestion due to a huge increase in vehicle ownership has necessitated a major upgrade in road infrastructure.[18]

The main international airport, Faleolo International Airport, is a 40-minute drive west of the city. Samoa's major domestic airlines, Polynesian Airlines and Talofa Airways, service this airport. Fagali'i Airport, the small airstrip in Fagali'i, was used for internal flights and some international flights to Pago Pago in American Samoa.[19]

Education

[edit]Apia is home to a number of pre-schools, primary, secondary and post-secondary institutions,[20] including Samoa's only university, the National University of Samoa. In addition, the University of the South Pacific School of Agriculture maintains a campus at Alafua,[21] on the outskirts of Apia. Another major school in Apia is Robert Louis Stevenson School which is a private primary and secondary school. Robert Louis Stevenson school is known as Samoa's upper class school, due to many children of Samoa's wealthy classes attending it.

Universities

[edit]Colleges in Upolu Island

[edit]- LDS Church College of Pesega, Pesega

- Faatuatua Christian College, Vaitele Fou

- Kolisi o Sagata Maria, also called St Mary's College, Vaimoso

- Leififi College, Leififi

- Leulumoega-fou College, Malua

- Maluafou College, Maluafou

- Saint Joseph's College, Alafua

- Samoa College, Vaivase Tai

- Seventh Day Adventist College, Lalovaea

- Robert Louis Stevenson College, Tafaigata

- Wesley College, Faleula

- Nuuausala College, Nofoalii

- Paul V1 College, Leulumoega Tuai

- Chanel College, Moamoa

- Avele College, Vailima

- Lepa Lotofaga College

- Palalaua College, Siumu

- Aleipata College

- Anoamaa College

- Falealili College

- Safata College

- Aana No. 1 College

- Aana No. 2 College

- Sagaga College

Colleges in Savaii Island

[edit]- Tuasivi College

- LDS Church College of Vaiola

- Wesleyan College (Uesiliana)

- Don Bosco College

- Itu O Tane College

- Palauli College

- Palauli I Sisifo College

- Amoa College

- Vaimauga College

- Papauta Girls College

- Mataevave College

Primary schools

[edit]Most of the villages have their own primary schools, but the Churches run most of the primary schools in downtown Apia.

- Robert Louis Stevenson School, Lotopa

- Marist Brothers' School, Mulivai

- Saint Mary's School, Savalalo

- Peace Chapel School, Vaimea

- Apia Baptist School, Aai o Niue

- Seventh-day Adventist Primary School, Lalovaea

- All Saints Anglican School, Malifa

Sport

[edit]Pacific Games

[edit]Apia hosted the Pacific Games in 1983 for the first time in the country's history. The Games returned to Apia for the 2007 Pacific Games, in which Samoa finished third. A crowd of 20,000 attended the 2007 Games closing ceremony at Apia Park.[22]

Association football

[edit]Apia hosted the Oceania region's qualification matches for the 2010 FIFA World Cup. As such, Apia was the location of the first goal scored in the 2010 qualifiers, by Pierre Wajoka of New Caledonia against Tahiti.[23] The qualification matches commenced on 27 August 2007 and finished on 7 September 2007.[24] All matches were played at the Toleafoa J.S. Blatter Complex, which is named after FIFA president Sepp Blatter.

The complex, based in Apia, is also the venue of the Samoa national football team's home matches and has a capacity of 3,500.

Judo

[edit]The capital also hosted from 2009 to 2012 the IJF Judo World Cup, which was downgraded in 2013 to become a regional tournament called the 'Oceania Open'.[25]

Cricket

[edit]Apia hosted the 2012 ICC World Cricket League Division Eight tournament at the Faleata Oval's, which consists of four cricket grounds. The national teams of Samoa, Belgium, Japan, Suriname, Ghana, Bhutan, Norway and Vanuatu took part. It was the first time a tournament officially sanctioned by the International Cricket Council had been held in the region.[26]

Basketball

[edit]Apia hosted the 2018 FIBA Polynesia Basketball Cup where Samoa's national basketball team finished runner-up.

Sister cities

[edit] Shenzhen, Guangdong, China (2015)[27]

Shenzhen, Guangdong, China (2015)[27] Compton, California, United States (2010)[28]

Compton, California, United States (2010)[28] Oranjestad, Aruba (2012)

Oranjestad, Aruba (2012) Riohacha, Colombia (2019)

Riohacha, Colombia (2019) Taipei, Republic of China

Taipei, Republic of China

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Weather Underground: Apia, Samoa".

- ^ a b "Population and Housing Census Report 2006" (PDF). Samoa Bureau of Statistics. July 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ^ "Samoa", Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ "Hurricane at Apia, Samoa 15-16 March 1889". US Department of Navy, Naval Historical Center. 24 March 2002. Archived from the original on 4 April 2002. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ MacLean, James (2 February 2005). "Imperialism as a Vocation: Class C Mandates". Archived from the original on 25 August 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- ^ Ministry for Culture and Heritage (2 September 2014). "The rise of the Mau movement - New Zealand in Samoa | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". Nzhistory.net.nz. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ Built of US Navy basesUS Navy

- ^ "Straw | Operations & Codenames of WWII". codenames.info.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Apia". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 3 January 2024.

- ^ "Environmental and Social Management Framework for the Samoa Agriculture Competitiveness Enhancement Project" (PDF). World Bank. 2 December 2011. p. 54. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- ^ "Planning and Urban Management Act 2004". PACLII. 21 January 2004. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "Scot of the South Seas: Robert Louis Stevenson in Samoa". The New Statesman. Retrieved 13 February 2025.

- ^ "Falemata'aga | Apia, Samoa Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ "Baha'i House of Worship of Samoa". bahaisamoa. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ "Our Company Archived 27 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine." Polynesian Airlines. Retrieved on 23 October 2009.

- ^ Chang, Richard S. (8 September 2009). "In Samoa, Drivers Switch to Left Side of the Road". The New York Times.

- ^ Tavita, Tupuola Terry (2 July 2012). "Convent Street, first phase in capital development". Savali News.

- ^ "Parking Policy Statement" (PDF). Newsline. MNRE. 19 November 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2012.

- ^ Sagapolutele, Fili. "Polynesian to resume flying into Fagali'i airport this week". Samoa News. SamoaNews.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2011.

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Nations: Samoa Education

- ^ "University of South Pacific: Alafua Campus". Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ "Unprecedented fireworks display closes 13th South Pacific Games". RNZ. 10 September 2007. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ "Oceania FIFA World Cup qualifying review". M.fifa.com. 12 January 2017. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ "futbolplanet.de". futbolplanet.de. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ "IJF World Cup Apia, Event, JudoInside". Judoinside.com. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- ^ "World Cricket League Division 8, Apia (Samoa), September 2012". cricketeurope4.net. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ "Apia signs sister-city agreement with Shenzhen". samoagovt.ws. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ "Sister Cities of Compton". comptonsistercities.org. Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

External links

[edit]- View of Apia, the Capital of Samoa, One of the Islands in the Pacific Ocean, from Harper's Weekly, 12 January 1895 by D.J. Kennedy, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

History

Pre-colonial and early European contact

The Samoan archipelago, encompassing the island of Upolu where Apia is located, was initially settled by Austronesian voyagers of the Lapita culture between 2,880 and 2,750 years ago, with archaeological evidence from sites like Mulifanua indicating early pottery and human activity dating to approximately 750–550 BCE.[6] These settlers established villages along coastal areas, including proto-settlements in the Apia region, relying on fishing, taro cultivation, and communal resource management under a hierarchical social structure. Oral traditions preserved in Samoan genealogy (gafa) recount migrations from Fiji and Tonga, fostering a distinct Polynesian identity centered on extended family units (aiga).[7] Pre-colonial Samoan society in the Apia vicinity operated under the faʻamatai system, where titled chiefs (matai) inherited leadership roles through family consensus, overseeing village councils (fono) and communal land tenure to ensure collective welfare and dispute resolution.[8] Matai authority emphasized reciprocity (faʻalavelave) and adherence to customs (faʻa Samoa), with Apia's early villages functioning as hubs for inter-island exchange and chiefly alliances, as evidenced by artifact distributions suggesting trade networks predating European arrival. This system maintained social stability amid environmental challenges like cyclones, without centralized kingship but through district-level coordination. The first recorded European sighting of Samoa occurred on June 13, 1722, when Dutch navigator Jacob Roggeveen approached the Manuʻa Islands from the east, noting high islands and brief interactions marked by mutual suspicion and minor skirmishes that deterred prolonged contact.[9] Roggeveen's expedition, seeking Terra Australis, documented Samoans as robust seafarers with outrigger canoes, but departed after limited bartering, leaving no lasting imprint. Sporadic French and British voyages followed, such as Louis-Antoine de Bougainville's 1768 passage, yet these remained exploratory without settlement. Christian missionaries initiated sustained European engagement in the 1830s, with London Missionary Society agents John Williams and Charles Barff arriving on August 16, 1830, at Sapapaliʻi on Savaiʻi, where they secured the allegiance of paramount chief Malietoa Vainuʻu, facilitating rapid conversion across islands including Upolu's Apia district.[10] Wesleyan Methodists, led by Peter Turner, established a station in Apia by 1835, introducing literacy and trade goods that intertwined with local chiefly networks, though initial adaptations preserved matai oversight. By 1839, over half of Upolu's population had embraced Christianity, transforming social rituals while Apia evolved as an early nexus for missionary outposts and passing vessels.[11]Colonial administration and conflicts

In the late 1880s, Apia became the focal point of imperial rivalries among Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom, as each power sought influence over Samoa's strategic harbors and copra trade. By March 1889, three American warships—USS Trenton, Vandalia, and Nipsic—joined three German vessels—SMS Adler, Eber, and Olga—and the British HMS Calliope in Apia Harbor, amid escalating tensions that risked naval confrontation.[12][13] On March 15–16, 1889, a powerful cyclone struck, wrecking the American and German ships with significant loss of life—over 140 sailors perished—and beaching others, while HMS Calliope escaped under full steam, averting potential war among the powers.[12][13] The crisis prompted the General Act of Berlin on June 14, 1889, establishing a joint protectorate with shared administration among the three powers, though implementation faltered amid ongoing Samoan civil strife and foreign interference.[14] This tridominium period, lasting until 1899, saw Apia as the de facto administrative hub, but governance was ineffective, marked by competing consular influences and local resistance to foreign meddling. The Tripartite Convention of December 2, 1899—ratified and proclaimed by February 16, 1900—resolved the impasse by partitioning Samoa: Germany acquired the western islands including Apia, forming German Samoa; the United States took the eastern group as American Samoa; and Britain received compensatory interests elsewhere, such as Tonga.[15] Under German rule from 1900 to 1914, Apia served as the capital and primary port, with administration centered on expanding copra plantations dominated by firms like the Deutsch Handels- und Plantations-Gesellschaft (DHPG), which drove economic development through labor recruitment and infrastructure like roads and a government district in Apia.[16] German policies emphasized efficient colonial governance but faced "renegade" resistance from Samoans opposing land alienation and taxation, challenging the notion of a non-violent administration.[17] World War I ended German control when New Zealand forces occupied Apia unopposed on August 29, 1914, interning German officials and assuming administration.[18] In 1920, the League of Nations granted New Zealand a Class C Mandate over Western Samoa, with Apia remaining the administrative center under military governance that prioritized stability and export economies like copra, though it encountered local Mau movement protests against perceived authoritarianism.[19] This mandate persisted through World War II, bridging imperial transitions until post-war decolonization pathways emerged.[19]Independence and post-colonial era

Samoa achieved independence from New Zealand administration on January 1, 1962, becoming the Independent State of Western Samoa and the first Pacific island nation to regain sovereignty in the 20th century, with Apia designated as the capital and administrative center.[20][21] The new constitution established a parliamentary democracy that integrated the traditional fa'amatai chiefly system—where matai titleholders lead villages and hold political authority—with elements of the Westminster model, requiring parliamentary candidates to possess matai titles to ensure cultural continuity in governance.[22][23] Apia, as the seat of government on Mulinu'u Peninsula, hosted key institutions like the Legislative Assembly and judiciary, fostering political stability amid post-colonial nation-building.[24] In July 1997, a constitutional amendment shortened the country's name to Samoa, reflecting a move toward cultural self-assertion while retaining Apia as the capital amid growing urbanization.[25][26] Post-independence population growth and rural-to-urban migration expanded Apia's boundaries, with the urban area encompassing about 22% of Samoa's population by the early 2000s, driven by economic opportunities in administration, trade, and services.[22][27] This development strained infrastructure but solidified Apia's role as the economic and political hub, with policies emphasizing sustainable urban financing to accommodate sprawl.[28] The matai system's influence persisted in politics, promoting consensus-based leadership through village councils (fono), though it limited broader participation until universal adult suffrage was extended in 1990.[23] A 2019 constitutional reform mandated a minimum 10% quota for women in the Legislative Assembly to address underrepresentation, as matai titles were historically male-dominated, marking a targeted evolution in electoral practices without altering the chiefly candidacy requirement.[29][30] This measure aimed to balance tradition with democratic inclusion, sustaining Samoa's record of stable governance centered in Apia.[31]Recent political and social developments

In the April 2021 general elections, Samoa's Fa'atuatua i le Atua Samoa ua Tasi (FAST) party secured 25 of 50 contested seats plus additional allocations under constitutional gender quota provisions, enabling Fiame Naomi Mata'afa to become the nation's first female prime minister after 22 years of Human Rights Protection Party (HRPP) rule.[32] A subsequent constitutional crisis arose when the outgoing HRPP government, based in Apia, locked the parliamentary chamber to block the new session's convening on May 24, aiming to nullify the quota law's implementation—which mandates adding the highest-polling unsuccessful female candidates if fewer than 10% of seats are held by women—thereby preserving HRPP's perceived majority.[33][34] The Supreme Court intervened on May 20, ruling the delay unlawful and affirming the quotas' validity under the 2013 constitutional amendment, allowing FAST to form government and averting prolonged deadlock in the capital.[35] Political tensions persisted into 2025, culminating in Prime Minister Fiame's dissolution of parliament on July 25 after opposition rejection of her budget amid internal FAST fractures and cost-of-living protests in Apia.[36] Snap elections on August 29 saw FAST retain power with a confirmed victory, though voter turnout reflected dissatisfaction with blackouts, inflation, and governance amid geopolitical influences like China's regional aid.[37][38] This instability, centered in Apia's Mulinu'u Peninsula government precinct, highlighted ongoing elite rivalries within Samoa's fa'amatai chiefly system intersecting with democratic processes.[39] Socially, Apia's rapid urbanization has intensified since 2010 due to rural-to-urban migration driven by access to education, healthcare, and employment, with the capital absorbing over 70% of Samoa's urban population growth and straining infrastructure like water supply and sanitation.[40] This influx, comprising families relocating from outer islands, has fostered informal settlements and landlessness, as communal land tenure limits individual ownership, exacerbating vulnerability during events like the 2022 measles outbreak that originated in Apia.[41] Remittances from Samoan diaspora—totaling 20-25% of GDP annually, primarily from New Zealand, Australia, and the United States—bolster household incomes in Apia but sustain uneven development, with urban poor relying on church networks for support amid rising living costs post-COVID border closures.[42][43]Geography

Location and topography

Apia lies on the northern coast of Upolu Island, the principal island of Samoa, at coordinates 13°49′S 171°46′W.[2] Positioned at the mouth of the Vaisigano River, the city centers around a natural harbor fronted by fringing coral reefs that provide shelter from open ocean swells.[44] These reefs, including areas like Palolo Deep adjacent to the harbor entrance, form a barrier influencing marine access and coastal sedimentation patterns critical to port functionality.[45] The terrain features low-lying coastal plains, averaging elevations of 2 to 13 meters above sea level, that extend narrowly inland before ascending to rugged volcanic highlands.[44][46] Mount Vaea, reaching 472 meters, exemplifies the steep rise to the island's interior, shaped by Upolu's origins as a basaltic shield volcano emerging from the Pacific seafloor.[44][47] This topography confines urban expansion to the alluvial plains while directing drainage from mountainous catchments into the harbor, historically supporting settlement and agriculture proximate to the coast. Across the Apolima Strait, Savai'i Island lies approximately 56 kilometers west, its volcanic peaks visible from Apia and occasionally impacting regional visibility during eruptions due to ash dispersal.[48] The strait's width facilitates inter-island ferry trade but exposes Apia to potential seismic influences from the Samoan hotspot chain.[48]