Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Tuvalu

View on Wikipedia

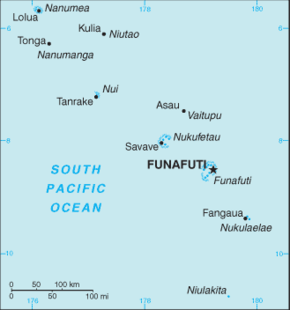

Tuvalu (/tuːˈvɑːluː/ ⓘ too-VAH-loo)[5] is an island country in the Polynesian sub-region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean, about midway between Hawaii and Australia. It lies east-northeast of the Santa Cruz Islands (which belong to the Solomon Islands), northeast of Vanuatu, southeast of Nauru, south of Kiribati, west of Tokelau, northwest of Samoa and Wallis and Futuna, and north of Fiji.

Key Information

Tuvalu is composed of three reef islands and six atolls spread out between the latitude of 5° and 10° south and between the longitude of 176° and 180°. They lie west of the International Date Line.[6] The 2022 census determined that Tuvalu had a population of 10,643,[7]: 5 making it the 194th most populous country, exceeding only Niue and the Vatican City in population. Tuvalu's total land area is 25.14 square kilometres (9.71 sq mi).[7]

The first inhabitants of Tuvalu were Polynesians arriving as part of the migration of Polynesians into the Pacific that began about three thousand years ago.[8] Long before European contact with the Pacific islands, Polynesians frequently voyaged by canoe between the islands. Polynesian navigation skills enabled them to make elaborately planned journeys in either double-hulled sailing canoes or outrigger canoes.[9] Scholars believe that the Polynesians spread out from Samoa and Tonga into the Tuvaluan atolls, which then served as a stepping stone for further migration into the Polynesian outliers in Melanesia and Micronesia.[10][11][12]

In 1568, Spanish explorer and cartographer Álvaro de Mendaña became the first European known to sail through the archipelago, sighting the island of Nui during an expedition he was making in search of Terra Australis. The island of Funafuti, currently serving as the capital, was named Ellice's Island in 1819. Later, the whole group was named Ellice Islands by English hydrographer Alexander George Findlay. In the late 19th century, Great Britain claimed control over the Ellice Islands, designating them as within their sphere of influence.[13] Between 9 and 16 October 1892, Captain Herbert Gibson of HMS Curacoa declared each of the Ellice Islands a British protectorate. Britain assigned a resident commissioner to administer the Ellice Islands as part of the British Western Pacific Territories (BWPT). From 1916 to 1975, they were managed as part of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony.

A referendum was held in 1974 to determine whether the Gilbert Islands and Ellice Islands should each have their own administration.[14] As a result, the Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony legally ceased to exist on 1 October 1975; on 1 January 1976, the old administration was officially separated,[15] and two separate British colonies, Kiribati and Tuvalu, were formed. On 1 October 1978, Tuvalu became fully independent as a sovereign state within the Commonwealth, and is a constitutional monarchy with Charles III as King of Tuvalu. On 5 September 2000, Tuvalu became the 189th member of the United Nations.

The islands do not have a significant amount of soil, so the country relies heavily on imports and fishing for food. Licensing fishing permits to international companies, grants and aid projects, and remittances to their families from Tuvaluan seafarers who work on cargo ships are important parts of the economy. Because it is a low-lying island nation, Tuvalu is extremely vulnerable to sea level rise due to climate change.[16] It is active in international climate negotiations as part of the Alliance of Small Island States.

History

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]The origins of the people of Tuvalu are addressed in the theories regarding the migration into the Pacific that began about 3,000 years ago. During pre-European-contact times, there was frequent canoe voyaging between the nearer islands including Samoa and Tonga.[17] Eight of the nine islands of Tuvalu were inhabited. This explains the origin of the name, Tuvalu, which means 'eight standing together' in Tuvaluan (compare to *walu meaning 'eight' in Proto-Austronesian). Possible evidence of human-made fires in the Caves of Nanumanga suggests humans may have occupied the islands for thousands of years.

An important creation myth in the islands of Tuvalu is the story of te Pusi mo te Ali (the Eel and the Flounder), who are said to have created the islands of Tuvalu. Te Ali (the flounder) is believed to be the origin of the flat atolls of Tuvalu and te Pusi (the eel) is the model for the coconut palms that are important in the lives of Tuvaluans. The stories of the ancestors of the Tuvaluans vary from island to island. On Niutao,[18] Funafuti and Vaitupu, the founding ancestor is described as being from Samoa,[19][20] whereas on Nanumea, the founding ancestor is described as being from Tonga.[19]

Early contacts with other cultures

[edit]

Tuvalu was first sighted by Europeans on 16 January 1568, during the voyage of Álvaro de Mendaña from Spain, who sailed past Nui and charted it as Isla de Jesús (Spanish for "Island of Jesus") because the previous day was the feast of the Holy Name. Mendaña made contact with the islanders but was unable to land.[22][23] During Mendaña's second voyage across the Pacific, he passed Niulakita on 29 August 1595, which he named La Solitaria.[23][24]

Captain John Byron passed through the islands of Tuvalu in 1764, during his circumnavigation of the globe as captain of the Dolphin (1751).[25] He charted the atolls as Lagoon Islands. The first recorded sighting of Nanumea by Europeans was by Spanish naval officer Francisco Mourelle de la Rúa who sailed past it on 5 May 1781 as captain of the frigate La Princesa, when attempting a southern crossing of the Pacific from the Philippines to New Spain. He charted Nanumea as San Augustin.[26][27] Keith S. Chambers and Doug Munro (1980) identified Niutao as the island that Mourelle also sailed past on 5 May 1781, thus solving what Europeans had called The Mystery of Gran Cocal.[24][28] Mourelle's map and journal named the island El Gran Cocal ('The Great Coconut Plantation'); however, the latitude and longitude was uncertain.[28] Longitude could be reckoned only crudely at the time, as accurate chronometers did not become available until the late 18th century.

In 1809, Captain Patterson in the brig Elizabeth sighted Nanumea while passing through the northern Tuvalu waters on a trading voyage from Port Jackson, Sydney, Australia to China.[26] In May 1819, Arent Schuyler de Peyster, of New York, captain of the armed brigantine or privateer Rebecca, sailing under British colours,[29][30] passed through the southern Tuvaluan waters. De Peyster sighted Nukufetau, and Funafuti which he named Ellice's Island after an English politician, Edward Ellice, the Member of Parliament for Coventry and the owner of the Rebecca's cargo.[28][31][32] The name Ellice was applied to all nine islands after the work of English hydrographer Alexander George Findlay.[33]

In 1820, the Russian explorer Mikhail Lazarev visited Nukufetau as commander of the Mirny.[28] Louis-Isidore Duperrey, captain of La Coquille, sailed past Nanumanga in May 1824 during a circumnavigation of the Earth (1822–1825).[34] A Dutch expedition by the frigate Maria Reigersberg[35] under captain Koerzen, and the corvette Pollux under captain C. Eeg, found Nui on the morning of 14 June 1825 and named the main island (Fenua Tapu) as Nederlandsch Eiland.[36]

Whalers began roving the Pacific, although they visited Tuvalu only infrequently because of the difficulties of landing on the atolls. The American Captain George Barrett of the Nantucket whaler Independence II has been identified as the first whaler to hunt the waters around Tuvalu.[31] He bartered coconuts from the people of Nukulaelae in November 1821, and also visited Niulakita.[24] He established a shore camp on Sakalua islet of Nukufetau, where coal was used to melt down the whale blubber.[37]

Christianity came to Tuvalu in 1861 when Elekana, a deacon of a Congregational church in Manihiki, Cook Islands, became caught in a storm and drifted for eight weeks before landing at Nukulaelae on 10 May 1861.[28][38] Elekana began preaching Christianity. He was trained at Malua Theological College, a London Missionary Society (LMS) school in Samoa, before beginning his work in establishing the Church of Tuvalu.[28] In 1865, the Rev. Archibald Wright Murray of the LMS, a Protestant congregationalist missionary society, arrived as the first European missionary; he also evangelised among the inhabitants of Tuvalu. By 1878 Protestantism was considered well established, as there were preachers on each island.[28] In the later 19th and early 20th centuries, the ministers of what became the Church of Tuvalu (Te Ekalesia Kelisiano Tuvalu) were predominantly Samoans,[39] who influenced the development of the Tuvaluan language and the music of Tuvalu.[40]

For less than a year between 1862 and 1863, Peruvian ships engaged in the so-called "blackbirding" trade, by which they recruited or impressed workers, combed the smaller islands of Polynesia from Easter Island in the eastern Pacific to Tuvalu and the southern atolls of the Gilbert Islands (now Kiribati). They sought recruits to fill the extreme labour shortage in Peru.[41] On Funafuti and Nukulaelae, the resident traders facilitated the recruiting of the islanders by the "blackbirders".[42] The Rev. Archibald Wright Murray,[43] the earliest European missionary in Tuvalu, reported that in 1863 about 170 people were taken from Funafuti and about 250 were taken from Nukulaelae,[28] as there were fewer than 100 of the 300 recorded in 1861 as living on Nukulaelae.[44][45]

The islands came into Britain's sphere of influence in the late 19th century, when each of the Ellice Islands was declared a British protectorate by Captain Herbert Gibson of HMS Curacoa, between 9 and 16 October 1892.[46]

Trading firms and traders

[edit]

Trading companies became active in Tuvalu in the mid-19th century; the trading companies engaged white (palagi) traders who lived on the islands. John (also known as Jack) O'Brien was the first European to settle in Tuvalu; he became a trader on Funafuti in the 1850s. He married Salai, the daughter of the paramount chief of Funafuti. Louis Becke, who later found success as a writer, was a trader on Nanumanga from April 1880 until the trading station was destroyed later that year in a cyclone.[47] He then became a trader on Nukufetau.[48][49][50]

In 1892, Captain Edward Davis of HMS Royalist reported on trading activities and traders on each of the islands visited. Captain Davis identified the following traders in the Ellice Group: Edmund Duffy (Nanumea); Jack Buckland (Niutao); Harry Nitz (Vaitupu); Jack O'Brien (Funafuti); Alfred Restieaux and Emile Fenisot (Nukufetau); and Martin Kleis (Nui).[51][52] During this time, the greatest number of palagi traders lived on the atolls, acting as agents for the trading companies. Some islands would have competing traders, while dryer islands might only have a single trader.[42]

In the 1890s, structural changes occurred in the operation of the Pacific trading companies; they moved from a practice of having traders resident on each island to instead becoming a business operation where the supercargo (the cargo manager of a trading ship) would deal directly with the islanders when a ship visited an island.[42] After the high point in the 1880s,[42] the numbers of palagi traders in Tuvalu declined; the last of them were Fred Whibley on Niutao, Alfred Restieaux on Nukufetau,[53][54] and Martin Kleis on Nui.[52] By 1909 there were no more resident palagi traders representing the trading companies,[52][42] although Whibley, Restieaux and Kleis[55] remained in the islands until their deaths.

Scientific expeditions and travellers

[edit]

The United States Exploring Expedition under Charles Wilkes visited Funafuti, Nukufetau, and Vaitupu in 1841.[56] During this expedition, engraver and illustrator Alfred Thomas Agate recorded the dress and tattoo patterns of the men of Nukufetau.[57]

In 1885 or 1886, the New Zealand photographer Thomas Andrew visited Funafuti[58] and Nui.[59][60]

In 1890, Robert Louis Stevenson, his wife Fanny Vandegrift Stevenson and her son Lloyd Osbourne sailed on the Janet Nicoll, a trading steamer owned by Henderson and Macfarlane of Auckland, New Zealand, which operated between Sydney and Auckland and into the central Pacific.[61] The Janet Nicoll visited three of the Ellice Islands;[62] while Fanny records that they made landfall at Funafuti, Niutao and Nanumea, Jane Resture suggests that it was more likely they landed at Nukufetau rather than Funafuti,[63] as Fanny describes meeting Alfred Restieaux and his wife Litia; however, they had been living on Nukufetau since the 1880s.[53][54] An account of this voyage was written by Fanny Stevenson and published under the title The Cruise of the Janet Nichol,[64] together with photographs taken by Robert Louis Stevenson and Lloyd Osbourne.

In 1894, Count Rudolf Festetics de Tolna, his wife Eila (née Haggin) and her daughter Blanche Haggin visited Funafuti aboard the yacht Le Tolna.[65] The Count spent several days photographing men and women on Funafuti.[66][67]

Photograph by Harry Clifford Fassett

The boreholes on Funafuti, at the site now called Darwin's Drill,[68] are the result of drilling conducted by the Royal Society of London for the purpose of investigating the formation of coral reefs to determine whether traces of shallow water organisms could be found at depth in the coral of Pacific atolls. This investigation followed the work on The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs conducted by Charles Darwin in the Pacific. Drilling occurred in 1896, 1897 and 1898.[69] Professor Edgeworth David of the University of Sydney was a member of the 1896 "Funafuti Coral Reef Boring Expedition of the Royal Society", under Professor William Sollas and led the expedition in 1897.[70] Photographers on these trips recorded people, communities, and scenes at Funafuti.[71]

Charles Hedley, a naturalist at the Australian Museum, accompanied the 1896 expedition, and during his stay on Funafuti he collected invertebrate and ethnological objects. The descriptions of these were published in Memoir III of the Australian Museum Sydney between 1896 and 1900. Hedley also wrote the General Account of the Atoll of Funafuti, The Ethnology of Funafuti,[72] and The Mollusca of Funafuti.[73][74] Edgar Waite was also part of the 1896 expedition and published The mammals, reptiles, and fishes of Funafuti.[75] William Rainbow described the spiders and insects collected at Funafuti in The insect fauna of Funafuti.[76]

Harry Clifford Fassett, captain's clerk and photographer, recorded people, communities and scenes at Funafuti in 1900 during a visit of USFC Albatross when the United States Fish Commission was investigating the formation of coral reefs on Pacific atolls.[77]

Colonial administration

[edit]

The Ellice Islands were administered as a British Protectorate from 1892 to 1916, as part of the British Western Pacific Territories (BWPT), by a Resident Commissioner based in the Gilbert Islands. The administration of the BWPT ended in 1916, and the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony was established, which existed until October 1975.

Second World War

[edit]During the Second World War, as a British colony the Ellice Islands were aligned with the Allies of the war. Early in the war, the Japanese invaded and occupied Makin, Tarawa and other islands in what is now Kiribati. The United States Marine Corps landed on Funafuti on 2 October 1942,[78] and on Nanumea and Nukufetau in August 1943. Funafuti was used as a base to prepare for the subsequent seaborne attacks on the Gilbert Islands (Kiribati) that were occupied by Japanese forces.[79]

The islanders assisted the American forces to build airfields on Funafuti, Nanumea and Nukufetau and to unload supplies from ships.[80] On Funafuti, the islanders shifted to the smaller islets so as to allow the American forces to build the airfield and Naval Base Funafuti on Fongafale.[81] A Naval Construction Battalion (Seabees) built a seaplane ramp on the lagoon side of Fongafale islet, for seaplane operations by both short- and long-range seaplanes, and a compacted coral runway was also constructed on Fongafale,[82] with runways also constructed to create Nanumea Airfield[83] and Nukufetau Airfield.[84] USN Patrol Torpedo Boats (PTs) and seaplanes were based at Naval Base Funafuti from 2 November 1942 to 11 May 1944.[85]

The atolls of Tuvalu acted as staging posts during the preparation for the Battle of Tarawa and the Battle of Makin that commenced on 20 November 1943, which were part of the implementation of "Operation Galvanic".[86][87] After the war, the military airfield on Funafuti was developed into Funafuti International Airport.

Post-World War II – transition to independence

[edit]The formation of the United Nations after World War II resulted in the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization committing to a process of decolonisation; as a consequence, the British colonies in the Pacific started on a path to self-determination.[88][89]

In 1974, the ministerial government was introduced to the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony through a change to the Constitution. In that year a general election was held,[90] and a referendum was held in 1974 to determine whether the Gilbert Islands and Ellice Islands should each have their own administration.[91] As a consequence of the referendum, separation occurred in two stages. The Tuvaluan Order 1975, which took effect on 1 October 1975, recognised Tuvalu as a separate Crown Colony with its own government.[92] The second stage occurred on 1 January 1976, when separate administrations were created out of the civil service of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony.[93]: 169 [94]

In 1976, Tuvalu adopted the Tuvaluan dollar, whose currency circulates alongside the Australian dollar,[95][96] which was previously adopted in 1966.

Elections to the House of Assembly of the British Colony of Tuvalu were held on 27 August 1977, with Toaripi Lauti being appointed chief minister in the House of Assembly of the Colony of Tuvalu on 1 October 1977. The House of Assembly was dissolved in July 1978, with the government of Toaripi Lauti continuing as a caretaker government until the 1981 elections were held.[97]

Post-Independence

[edit]Toaripi Lauti became the first prime minister on 1 October 1978, when Tuvalu became an independent state.[88][93]: 153–177 That date is also celebrated as the country's Independence Day and is a public holiday.[98]

On 26 October 1982, Queen Elizabeth II made a special royal tour to Tuvalu.

On 5 September 2000, Tuvalu became the 189th member of the United Nations.[99]

On 15 November 2022, amidst sea level rises, Tuvalu announced plans as the first country in the world to build a self-digital replica in the metaverse in order to preserve its cultural heritage.[100]

On 10 November 2023, Tuvalu signed the Falepili Union treaty with Australia.[101] In the Tuvaluan language, Falepili describes the traditional values of good neighbourliness, care and mutual respect.[102] The Treaty addresses climate change and security,[102] with security threats encompassing major natural disasters, health pandemics and traditional security threats.[102] The implementation of the Treaty will involve Australia increasing its contribution to the Tuvalu Trust Fund and the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project.[102] Australia will also provide a pathway for 280 citizens of Tuvalu to migrate to Australia each year, to enable climate-related mobility for Tuvaluans.[102][103]

Geography and environment

[edit]Geography

[edit]

Tuvalu is a volcanic archipelago, and consists of three reef islands (Nanumanga, Niutao and Niulakita) and six true atolls (Funafuti, Nanumea, Nui, Nukufetau, Nukulaelae and Vaitupu).[104] Its small, scattered group of low-lying atolls have poor soil and a total land area of only about 26 square kilometres (10 square miles) making it the fourth smallest country in the world. The highest elevation is 4.6 metres (15 ft) above sea level on Niulakita; however, the low-lying atolls and reef islands of Tuvalu are susceptible to seawater flooding during cyclones and storms.[105] The sea level at the Funafuti tide gauge has risen at 3.9 mm per year, which is approximately twice the global average.[106] However, over four decades, there had been a net increase in land area of the islets of 0.74 square kilometres (0.3 square miles) (2.9%), although the changes are not uniform, with 74% increasing and 27% decreasing in size. A 2018 report stated that the rising sea levels are identified as creating an increased transfer of wave energy across reef surfaces, which shifts sand, resulting in accretion to island shorelines.[104] The Tuvalu Prime Minister objected to the report's implication that there were "alternate" strategies for Islanders to adapt to rising sea levels, and criticised it for neglecting issues such as saltwater intrusion into groundwater tables as a result of sea level rise.[107]

Funafuti is the largest atoll, and comprises numerous islets around a central lagoon that is approximately 25.1 kilometres (15.6 miles) (N–S) by 18.4 kilometres (11.4 miles) (W-E), centred on 179°7'E and 8°30'S. On the atolls, an annular reef rim surrounds the lagoon with seven natural reef channels.[108] Surveys were carried out in May 2010 of the reef habitats of Nanumea, Nukulaelae and Funafuti; a total of 317 fish species were recorded during this Tuvalu Marine Life study. The surveys identified 66 species that had not previously been recorded in Tuvalu, which brings the total number of identified species to 607.[109][110] Tuvalu's exclusive economic zone (EEZ) covers an oceanic area of approximately 900,000 km2.[111]

Tuvalu signed the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992, and ratified it in December 2002.[112][113] The predominant vegetation type on the islands of Tuvalu is the cultivated coconut woodland, which covers 43% of the land. The native broadleaf forest is limited to 4.1% of the vegetation types,[114] with 40% of the native broadleaf forest of Funafuti contained in the Funafuti Conservation Area. Tuvalu contains the Western Polynesian tropical moist forests terrestrial ecoregion.[115]

Environmental pressures

[edit]

The eastern shoreline of Funafuti Lagoon on Fongafale was modified during World War II when the airfield (now Funafuti International Airport) was constructed. The coral base of the atoll was used as fill to create the runway. The resulting borrow pits impacted the fresh-water aquifer. In the low-lying areas of Funafuti, the sea water can be seen bubbling up through the porous coral rock to form pools with each high tide.[116][117] In 2014, the Tuvalu Borrow Pits Remediation (BPR) project was approved so that 10 borrow pits would be filled with sand from the lagoon, leaving Tafua Pond, which is a natural pond. The New Zealand Government funded the BPR project.[118] The project was carried out in 2015, with 365,000 sqm of sand being dredged from the lagoon to fill the holes and improve living conditions on the island. This project increased the usable land space on Fongafale by eight per cent.[119]

During World War II, several piers were also constructed on Fongafale in the Funafuti Lagoon; beach areas were filled and deep-water access channels were excavated. These alterations to the reef and shoreline resulted in changes to wave patterns, with less sand accumulating to form the beaches, compared to former times. Attempts to stabilise the shoreline did not achieve the desired effect.[120] In December 2022, work on the Funafuti reclamation project commenced, which is part of the Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project. Sand was dredged from the lagoon to construct a platform on Fongafale islet that is 780 metres (2,560 ft) meters long and 100 metres (330 ft) meters wide, giving a total area of approximately 7.8 ha. (19.27 acres), which is designed to remain above sea level rise and the reach of storm waves beyond the year 2100.[121] The platform starts from the northern boundary of the Queen Elizabeth Park (QEP) reclamation area and extends to the northern Tausoa Beach Groyne and the Catalina Ramp Harbour.[122]

The reefs at Funafuti suffered damage during the El Niño events that occurred between 1998 and 2001, with an average of 70% of the Staghorn (Acropora spp.) corals becoming bleached as a consequence of the increase in ocean temperatures.[123][124][125] A reef restoration project has investigated reef restoration techniques;[126] and researchers from Japan have investigated rebuilding the coral reefs through the introduction of foraminifera.[127] The project of the Japan International Cooperation Agency is designed to increase the resilience of the Tuvalu coast against sea level rise, through ecosystem rehabilitation and regeneration and through support for sand production.[128]

The rising population has resulted in an increased demand on fish stocks, which are under stress,[124] although the creation of the Funafuti Conservation Area has provided a fishing exclusion area to help sustain the fish population across the Funafuti lagoon.[129] Population pressure on the resources of Funafuti, and inadequate sanitation systems, have resulted in pollution.[130][131] The Waste Operations and Services Act of 2009 provides the legal framework for waste management and pollution control projects funded by the European Union directed at organic waste composting in eco-sanitation systems.[132] The Environment Protection (Litter and Waste Control) Regulation 2013 is intended to improve the management of the importation of non-biodegradable materials. Plastic waste is a problem in Tuvalu, for much imported food and other commodities are supplied in plastic containers or packaging.

In 2023 the governments of Tuvalu and other islands vulnerable to climate change (Fiji, Niue, the Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu) launched the "Port Vila Call for a Just Transition to a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific", calling for the phase out fossil fuels and the 'rapid and just transition' to renewable energy and strengthening environmental law including introducing the crime of ecocide.[133][134][135]

Climate

[edit]

Tuvalu experiences two distinct seasons, a wet season from November to April and a dry season from May to October.[136] Westerly gales and heavy rain are the predominant weather conditions from November to April, the period that is known as Tau-o-lalo, with tropical temperatures moderated by easterly winds from May to October.

Tuvalu experiences the effects of El Niño and La Niña, which is caused by changes in ocean temperatures in the equatorial and central Pacific. El Niño effects increase the chances of tropical storms and cyclones, while La Niña effects increase the chances of drought. Typically the islands of Tuvalu receive between 200 and 400 mm (8 and 16 in) of rainfall per month. The central Pacific Ocean experiences changes from periods of La Niña to periods of El Niño.[137]

| Climate data for Funafuti (Köppen Af) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.8 (92.8) |

34.4 (93.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.9 (91.2) |

32.8 (91.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.7 (87.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.8 (87.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 28.2 (82.8) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.2 (82.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 25.5 (77.9) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 22.0 (71.6) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

23.0 (73.4) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.0 (69.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 413.7 (16.29) |

360.6 (14.20) |

324.3 (12.77) |

255.8 (10.07) |

259.8 (10.23) |

216.6 (8.53) |

253.1 (9.96) |

275.9 (10.86) |

217.5 (8.56) |

266.5 (10.49) |

275.9 (10.86) |

393.9 (15.51) |

3,512.6 (138.29) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 20 | 19 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 16 | 18 | 17 | 19 | 223 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 82 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 81 | 82 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 179.8 | 161.0 | 186.0 | 201.0 | 195.3 | 201.0 | 195.3 | 220.1 | 210.0 | 232.5 | 189.0 | 176.7 | 2,347.7 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 5.8 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 6.3 | 5.7 | 6.4 |

| Source: Deutscher Wetterdienst[138] | |||||||||||||

Impact of climate change

[edit]As low-lying islands lacking a surrounding shallow shelf, the communities of Tuvalu are especially susceptible to changes in sea level and undissipated storms.[139][140][141] At its highest, Tuvalu is only 4.6 metres (15 ft) above sea level. Tuvaluan leaders have been concerned about the effects of rising sea levels.[142] It is estimated that a sea level rise of 20–40 centimetres (7.9–15.7 inches) in the next 100 years could make Tuvalu uninhabitable.[143][144] A study published in 2018 estimated the change in land area of Tuvalu's nine atolls and 101 reef islands between 1971 and 2014, indicating that 75% of the islands had grown in area, with an overall increase of more than 2%.[145] Enele Sopoaga, the prime minister of Tuvalu at the time, responded to the research by stating that Tuvalu is not expanding and has gained no additional habitable land.[146][147] Sopoaga has also said that evacuating the islands is the last resort.[148]

Whether there are measurable changes in the sea level relative to the islands of Tuvalu is a contentious issue.[149][150] There were problems associated with the pre-1993 sea level records from Funafuti which resulted in improvements in the recording technology to provide more reliable data for analysis.[144] The degree of uncertainty as to estimates of sea level change relative to the islands of Tuvalu was reflected in the conclusions made in 2002 from the available data.[144] The uncertainty as to the accuracy of the data from this tide gauge resulted in a modern Aquatrak acoustic gauge being installed in 1993 by the Australian National Tidal Facility (NTF) as part of the AusAID-sponsored South Pacific Sea Level and Climate Monitoring Project.[151] The 2011 report of the Pacific Climate Change Science Program published by the Australian Government,[152] concludes: "The sea-level rise near Tuvalu measured by satellite altimeters since 1993 is about 5 mm (0.2 in) per year."[153]

Tuvalu has adopted a national plan of action as the observable transformations over the last ten to fifteen years show Tuvaluans that there have been changes to the sea levels.[154] These include sea water bubbling up through the porous coral rock to form pools at high tide and the flooding of low-lying areas including the airport during spring tides and king tides.[116][117][155][156][157]

In November 2022, Simon Kofe, Minister for Justice, Communication & Foreign Affairs, proclaimed that in response to rising sea levels and the perceived failures by the outside world to combat global warming, the country would be uploading a virtual version of itself to the metaverse in an effort to preserve its history and culture.[158]

The major concerns about climate change has led to the launching and development of the National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA). These adaptation measures are needed to decrease the amount and volume of the negative effects from climate change. NAPA has selected seven adaptation projects with all different themes. These are: coastal, agricultural, water, health, fisheries (two different projects) and disaster. For example, a "target" of one of these projects, like the project "coastal", is "increasing resilience of coastal areas and settlement to climate change". And for the project "water" it is "adaptation to frequent water shortages through increasing household water capacity, water collection accessories, and water conservation techniques".[159]

The Tuvalu Coastal Adaptation Project (TCAP) was launched in 2017 for the purpose on enhancing the resilience of the islands of Tuvalu to meet the challenges resulting from higher sea levels.[160] Tuvalu was the first country in the Pacific to access climate finance from Green Climate Fund, with the support of the UNDP.[160] In December 2022, work on the Funafuti reclamation project commenced. The project is to dredge sand from the lagoon to construct a platform on Funafuti that is 780 metres (2,560 ft) meters long and 100 metres (330 ft) meters wide, giving a total area of approximately 7.8 ha. (19.27 acres), which is designed to remain above sea level rise and the reach of storm waves beyond the year 2100.[160] The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) also provided funding for the TCAP. Further projects that are part of TCAP are capital works on the outer islands of Nanumea and Nanumaga aimed at reducing exposure to coastal damage resulting from storms.[160]

Cyclones and king tides

[edit]Cyclones

[edit]

Because of the low elevation, the islands that make up this country are vulnerable to the effects of tropical cyclones and by the threat of current and future sea level rise.[130][161][162] A warning system, which uses the Iridium satellite network, was introduced in 2016 to allow outlying islands to be better prepared for natural disasters.[163]

The highest elevation is 4.6 metres (15 ft) above sea level on Niulakita.[164] Tuvalu thus has the second-lowest maximum elevation of any country (after the Maldives). The highest elevations are typically in narrow storm dunes on the ocean side of the islands which are prone to overtopping in tropical cyclones, as occurred with Cyclone Bebe, which was a very early-season storm that passed through the Tuvaluan atolls in October 1972.[165] Cyclone Bebe submerged Funafuti, eliminating 95% of structures on the island, with 6 people lost in the cyclone.[166] Sources of drinking water were contaminated as a result of the system's storm surge and the flooding of the sources of fresh water.[167]

George Westbrook, a trader on Funafuti, recorded a cyclone that struck Funafuti on 23–24 December 1883.[168] A cyclone struck Nukulaelae on 17–18 March 1886.[168] A cyclone caused severe damage to the islands in 1894.[169]

Tuvalu experienced an average of three cyclones per decade between the 1940s and 1970s; however, eight occurred in the 1980s.[105] The impact of individual cyclones is subject to variables including the force of the winds and also whether a cyclone coincides with high tides. Funafuti's Tepuka Vili Vili islet was devastated by Cyclone Meli in 1979, with all its vegetation and most of its sand swept away during the cyclone. Along with a tropical depression that affected the islands a few days later, Severe Tropical Cyclone Ofa had a major impact on Tuvalu with most islands reporting damage to vegetation and crops.[170][171] Cyclone Gavin was first identified during 2 March 1997, and was the first of three tropical cyclones to affect Tuvalu during the 1996–97 cyclone season, with Cyclones Hina and Keli following later in the season.

In March 2015, the winds and storm surge created by Cyclone Pam resulted in waves of 3 to 5 metres (9.8 to 16.4 ft) breaking over the reef of the outer islands, causing damage to houses, crops and infrastructure.[172][173] A state of emergency was declared. On Nui, the sources of fresh water were destroyed or contaminated.[174][175][176] The flooding in Nui and Nukufetau caused many families to shelter in evacuation centres or with other families.[177] Nui suffered the most damage of the three central islands (Nui, Nukufetau and Vaitupu);[178] with both Nui and Nukufetau suffering the loss of 90% of the crops.[179] Of the three northern islands (Nanumanga, Niutao and Nanumea), Nanumanga suffered the most damage, with from 60 to 100 houses flooded, with the waves also causing damage to the health facility.[179] Vasafua islet, part of the Funafuti Conservation Area, was severely damaged by Cyclone Pam. The coconut palms were washed away, leaving the islet as a sand bar.[180][181]

The Tuvalu Government carried out assessments of the damage caused by Cyclone Pam to the islands and has provided medical aid, food as well as assistance for the cleaning-up of storm debris. Government and Non-Government Organisations provided assistance technical, funding and material support to Tuvalu to assist with recovery, including WHO, UNICEF EAPRO, UNDP Asia-Pacific Development Information Programme, OCHA, World Bank, DFAT, New Zealand Red Cross & IFRC, Fiji National University and governments of New Zealand, Netherlands, UAE, Taiwan and the United States.[182]

Despite passing over 500 km (310 mi) to the south of the island nation, Cyclone Tino and its associated convergence zone impacted the whole of Tuvalu between January 16 - 19 of 2020.[183][184]

King tides

[edit]Tuvalu is also affected by perigean spring tide events which raise the sea level higher than a normal high tide.[185] The highest peak tide recorded by the Tuvalu Meteorological Service is 3.4 metres (11 ft), on 24 February 2006 and again on 19 February 2015.[186] As a result of the historical sea level rise, the king tide events lead to flooding of low-lying areas, which is compounded when sea levels are further raised by La Niña effects or local storms and waves.[187][188]

Water and sanitation

[edit]Rainwater harvesting is the principal source of fresh water in Tuvalu. Nukufetau, Vaitupu and Nanumea are the only islands with sustainable groundwater supplies. The effectiveness of rainwater harvesting is diminished because of poor maintenance of roofs, gutters and pipes.[189][190] Aid programmes of Australia and the European Union have been directed to improving the storage capacity on Funafuti and in the outer islands.[191]

Reverse osmosis (R/O) desalination units supplement rainwater harvesting on Funafuti. The 65 m3 desalination plant operates at a real production level of around 40 m3 per day. R/O water is only intended to be produced when storage falls below 30%; however, demand to replenish household storage supplies with tanker-delivered water means that the R/O desalination units are continually operating. Water is delivered at a cost of A$3.50 per m3. Cost of production and delivery has been estimated at A$6 per m3, with the difference subsidised by the government.[189]

In July 2012, a United Nations Special Rapporteur called on the Tuvalu Government to develop a national water strategy to improve access to safe drinking water and sanitation.[192][193] In 2012, Tuvalu developed a National Water Resources Policy under the Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) Project and the Pacific Adaptation to Climate Change (PACC) Project, which are sponsored by the Global Environment Fund/SOPAC. Government water planning has established a target of between 50 and 100L of water per person per day accounting for drinking water, cleaning, community and cultural activities.[189]

Tuvalu is working with the South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission (SOPAC) to implement composting toilets and to improve the treatment of sewage sludge from septic tanks on Fongafale, for septic tanks are leaking into the freshwater lens in the sub-surface of the atoll as well as the ocean and lagoon. Composting toilets reduce water use by up to 30%.[189]

Government

[edit]

Parliamentary democracy

[edit]The Constitution of Tuvalu states that it is "the supreme law of Tuvalu" and that "all other laws shall be interpreted and applied subject to this Constitution"; it sets out the Principles of the Bill of Rights and the Protection of the Fundamental Rights and Freedoms. On 5 September 2023, Tuvalu's parliament passed the Constitution of Tuvalu Act 2023,[194] with the changes to the constitution came into effect on 1 October 2023.[195]

Tuvalu is a parliamentary democracy and Commonwealth realm with Charles III as King of Tuvalu. Since the King resides in the United Kingdom, he is represented in Tuvalu by a governor general, whom he appoints upon the advice of the prime minister of Tuvalu.[97] Referendums were carried out in 1986 and 2008 seeking to abolish the monarchy and establish a republic, but on both occasions the monarchy was retained.

From 1974 (the creation of the British colony of Tuvalu) until independence, the legislative body of Tuvalu was called the House of the Assembly or Fale I Fono. Following independence in October 1978, the House of the Assembly was renamed the Parliament of Tuvalu or Palamene o Tuvalu.[97] The place at which the parliament sits is called the Vaiaku maneapa.[196] The maneapa on each island is an open meeting place where the chiefs and elders deliberate and make decisions.[196]

The unicameral Parliament has 16 members, with elections held every four years. The members of parliament select the Prime Minister (who is the head of government) and the Speaker of Parliament. The ministers that form the Cabinet are appointed by the Governor General on the advice of the Prime Minister. There are no formal political parties; election campaigns are largely based on personal/family ties and reputations.

The 2023 amendments to the Constitution recognise the Falekaupule as the traditional governing authorities of the islands of Tuvalu.[197]

The Tuvalu National Library and Archives holds "vital documentation on the cultural, social and political heritage of Tuvalu", including surviving records from the colonial administration, as well as Tuvalu government archives.[198]

Tuvalu is a state party to the following human rights treaties: the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC); the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and; the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).[199] Tuvalu has commitments to ensuring human rights are respected under the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The national strategy plan Te Kete – National Strategy for Sustainable Development 2021–2030 sets out the development agenda of the Government of Tuvalu,[200][201] which followed on from Te Kakeega III – National Strategy for Sustainable Development-2016-2020 (TK III). The areas of development in these strategic plans include education; climate change; environment; migration and urbanisation.[200][202]

The Tuvalu National Council for Women acts as an umbrella organisation for non-governmental women's rights groups throughout the country and works closely with the government.[203]

Legal system

[edit]There are eight Island Courts and Lands Courts; appeals in relation to land disputes are made to the Lands Courts Appeal Panel. Appeals from the Island Courts and the Lands Courts Appeal Panel are made to the Magistrates Court, which has jurisdiction to hear civil cases involving up to $T10,000. The superior court is the High Court of Tuvalu as it has unlimited original jurisdiction to determine the Law of Tuvalu and to hear appeals from the lower courts. Rulings of the High Court can be appealed to the Court of Appeal of Tuvalu. From the Court of Appeal, there is a right of appeal to His Majesty in Council, i.e., the Privy Council in London.[204][205]

With regard to the judiciary, "the first female Island Court magistrate was appointed to the Island Court in Nanumea in the 1980s and another in Nukulaelae in the early 1990s." There were 7 female magistrates in the Island Courts of Tuvalu (as of 2007) in comparison "to the past where only one woman magistrate served in the Magistrate Court of Tuvalu."[206]

The Law of Tuvalu comprises the Acts voted into law by the Parliament of Tuvalu and statutory instruments that become law; certain Acts passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom (during the time Tuvalu was either a British protectorate or British colony); the common law; and customary law (particularly in relation to the ownership of land).[204][205] The land tenure system is largely based on kaitasi (extended family ownership).[207]

Foreign relations

[edit]

Tuvalu participates in the work of the Pacific Community (SPC) and is a member of the Pacific Islands Forum, the Commonwealth of Nations and the United Nations. It has maintained a mission at the United Nations in New York City since 2000. Tuvalu became a member of the Asian Development Bank in 1993,[208] and became a member of the World Bank in 2010.[209]

Tuvalu maintains close relations with Fiji, New Zealand, Australia (which has maintained a High Commission in Tuvalu since 2018),[210] Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the United States of America, the United Kingdom and the European Union. It has diplomatic relations with Taiwan;[211][212][213] which maintains an embassy in Tuvalu and has a large assistance programme in the islands.[214][215]

A major international priority for Tuvalu in the UN, at the 2002 Earth Summit in Johannesburg, South Africa and in other international fora, is promoting concern about global warming and the possible sea level rising. Tuvalu advocates ratification and implementation of the Kyoto Protocol. In December 2009, the islands stalled talks on climate change at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen, fearing some other developing countries were not committing fully to binding deals on a reduction in carbon emissions. Their chief negotiator stated, "Tuvalu is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate change and our future rests on the outcome of this meeting."[216]

Tuvalu participates in the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), which is a coalition of small island and low-lying coastal countries that have concerns about their vulnerability to the adverse effects of global climate change. Under the Majuro Declaration, which was signed on 5 September 2013, Tuvalu has made a commitment to implement power generation of 100% renewable energy (between 2013 and 2020), which is proposed to be implemented using Solar PV (95% of demand) and biodiesel (5% of demand). The feasibility of wind power generation will be considered.[217] Tuvalu participates in the operations of the Pacific Islands Applied Geoscience Commission (SOPAC) and the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP).[218]

Tuvalu is party to a treaty of friendship with the United States, signed soon after independence and ratified by the US Senate in 1983, under which the United States renounced prior territorial claims to four Tuvaluan islands (Funafuti, Nukufetau, Nukulaelae and Niulakita) under the Guano Islands Act of 1856.[219]

Tuvalu participates in the operations of the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA)[220] and the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC).[221] The Tuvaluan government, the US government, and the governments of other Pacific islands are parties to the South Pacific Tuna Treaty (SPTT), which entered into force in 1988.[222] Tuvalu is also a member of the Nauru Agreement which addresses the management of tuna purse seine fishing in the tropical western Pacific. The United States and the Pacific Islands countries have negotiated the Multilateral Fisheries Treaty (which encompasses the South Pacific Tuna Treaty) to confirm access to the fisheries in the Western and Central Pacific for US tuna boats. Tuvalu and the other members of the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA) and the United States have settled a tuna fishing deal for 2015; a longer-term deal will be negotiated. The treaty is an extension of the Nauru Agreement and provides for the US flagged purse seine vessels to fish 8,300 days in the region in return for a payment of US$90 million made up by tuna fishing industry and US-Government contributions.[223] In 2015, Tuvalu refused to sell fishing days to certain nations and fleets that have blocked Tuvaluan initiatives to develop and sustain their own fishery.[224] In 2016, the Minister of Natural Resources drew attention to Article 30 of the WCPF Convention, which describes the collective obligation of members to consider the disproportionate burden that management measures might place on small-island developing states.[225]

In July 2013, Tuvalu signed the memorandum of understanding (MOU) to establish the Pacific Regional Trade and Development Facility, which Facility originated in 2006, in the context of negotiations for an Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) between Pacific ACP States and the European Union. The rationale for the creation of the Facility being to improve the delivery of aid to Pacific island countries in support of the Aid-for-Trade (AfT) requirements. The Pacific ACP States are the countries in the Pacific that are signatories to the Cotonou Agreement with the European Union.[226] On 31 May 2017 the first enhanced High Level Political Dialogue between Tuvalu and the European Union under the Cotonou Agreement was held in Funafuti.[227]

On 18 February 2016, Tuvalu signed the Pacific Islands Development Forum Charter and formally joined the Pacific Islands Development Forum (PIDF).[228] In June 2017, Tuvalu signed the Pacific Agreement on Closer Economic Relations (PACER).[229][230] Tuvalu ratified the PACER agreement in January 2022. The agreement is designed to reduce trade barriers between signatories of the agreement. Existing import tariffs will reduce to zero, and the agreement contemplates additional actions to reduce trade barriers, including harmonizing customs procedures and rules of origin, as well as eliminating restrictions to services trade, and improving labour mobility schemes between countries.[231]

Defence and law enforcement

[edit]Tuvalu has no regular military forces, and spends no money on the military. Its national police force, the Tuvalu Police Force headquartered in Funafuti, includes a maritime surveillance unit, customs, prisons and immigration. Police officers wear British-style uniforms.

From 1994 to 2019 Tuvalu policed its 200-kilometre exclusive economic zone with the Pacific-class patrol boat HMTSS Te Mataili, provided by Australia.[232] In 2019, Australia gifted a Guardian-class patrol boat as replacement.[233] Named HMTSS Te Mataili II, it is meant for use in maritime surveillance, fishery patrol and for search-and-rescue missions.[234] ("HMTSS" stands for His/Her Majesty's Tuvaluan State Ship or for His/Her Majesty's Tuvalu Surveillance Ship.) Te Mataili II was severely damaged by cyclones.[235] On 16 October 2024 Australia handed over a Guardian-class patrol boat to Tuvalu, which was named HMTSS Te Mataili III.[236]

In May 2023 the Government of Tuvalu signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Sea Shepherd Global, which is based in the Netherlands, to combat illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing in Tuvalu's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).[235] Sea Shepherd Global will provide the Allankay, a 54.6 metres (179 ft) motor vessel, to support Tuvalu's law enforcement activities.[235] Allankay will accommodate officers from the Tuvalu Police Force, who have the authority to board, inspect, and arrest fishing vessels engaged in IUU activity in Tuvalu's EEZ.[235]

Male homosexuality is illegal in Tuvalu.[237] Crime in Tuvalu is not a significant social problem due to an effective criminal justice system, also due to the influence of the Falekaupule (the traditional assembly of elders of each island) and the central role of religious institutions in the Tuvaluan community.

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Tuvalu consists of six atolls and three reef islands, each constituting a district of the country. The smallest, Niulakita, is administered as part of Niutao. The districts, their island counts, and their populations as of the 2022 census are as follows:

| District | Islets | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Funafuti | 6 | 6,602 |

| Nanumanga | 1 | 391 |

| Nanumea | 9 | 610 |

| Niulakita | 1 | 36 |

| Niutao | 1 | 550 |

| Nui | 21 | 514 |

| Nukufetau | 33 | 581 |

| Nukulaelae | 15 | 341 |

| Vaitupu | 9 | 1,007 |

Each island has its own high-chief (ulu-aliki), several sub-chiefs (alikis), and a community council (Falekaupule). The Falekaupule, also known as te sina o fenua (grey-hairs of the land), is the traditional assembly of elders.

The ulu-aliki and aliki exercise informal authority at the local level, with the former chosen on the basis of ancestry. Since the passage of the Falekaupule Act in 1997,[238] the powers and functions of the Falekaupule are shared with the pule o kaupule, a village president elected on each atoll.[239]

Tuvalu has ISO 3166-2 codes defined for one town council (Funafuti) and seven island councils. Niulakita, which now has its own island council, is not listed, as it is administered as part of Niutao.

Society

[edit]Demographics

[edit]

The population at the 2002 census was 9,561,[240] and the population at the 2017 census was 10,645.[241][242] The most recent evaluation in 2020 puts the population at 11,342.[243] The population of Tuvalu is primarily of Polynesian ethnicity, with approximately 5.6% of the population being Micronesians speaking Gilbertese, especially on Nui.[241]

Life expectancy for women in Tuvalu is 70.2 years and 65.6 years for men (2018 est.).[244] The country's population growth rate is 0.86% (2018 est.).[244] The net migration rate is estimated at −6.6 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2018 est.).[244] The threat of global warming in Tuvalu is not yet a dominant motivation for migration as Tuvaluans appear to prefer to continue living on the islands for reasons of lifestyle, culture and identity.[245]

From 1947 to 1983, a number of Tuvaluans from Vaitupu migrated to Kioa, an island in Fiji.[246] The settlers from Tuvalu were granted Fijian citizenship in 2005. In recent years, New Zealand and Australia have been the primary destinations for migration or seasonal work.

In 2014, attention was drawn to an appeal to the New Zealand Immigration and Protection Tribunal against the deportation of a Tuvaluan family on the basis that they were "climate change refugees", who would suffer hardship resulting from the environmental degradation of Tuvalu.[247] However, the subsequent grant of residence permits to the family was made on grounds unrelated to the refugee claim.[248] The family was successful in their appeal because, under the relevant immigration legislation, there were "exceptional circumstances of a humanitarian nature" that justified the grant of resident permits, for the family was integrated into New Zealand society with a sizeable extended family that had effectively relocated to New Zealand.[248] Indeed, in 2013 a claim of a Kiribati man of being a "climate change refugee" under the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (1951) was determined by the New Zealand High Court to be untenable, as there was no persecution or serious harm related to any of the five stipulated Refugee Convention grounds.[249] Permanent migration to Australia and New Zealand, such as for family reunification, requires compliance with the immigration legislation of those countries.[250]

New Zealand announced the Pacific Access Category in 2001, which provided an annual quota of 75 work permits for Tuvaluans.[251] The applicants register for the Pacific Access Category (PAC) ballots; the primary criterion is that the principal applicant must have a job offer from a New Zealand employer.[252] Tuvaluans also have access to seasonal employment in the horticulture and viticulture industries in New Zealand under the Recognised Seasonal Employer (RSE) Work Policy introduced in 2007 allowing for employment of up to 5,000 workers from Tuvalu and other Pacific islands.[253] Tuvaluans can participate in the Australian Pacific Seasonal Worker Program, which allows Pacific Islanders to obtain seasonal employment in the Australian agriculture industry, in particular, cotton and cane operations; fishing industry, in particular aquaculture; and with accommodation providers in the tourism industry.[254]

On 10 November 2023, Tuvalu signed the Falepili Union, a bilateral diplomatic relationship with Australia, under which Australia will provide a pathway for citizens of Tuvalu to migrate to Australia, to enable climate-related mobility for Tuvaluans.[101][102]

Languages

[edit]The Tuvaluan language and English are the national languages of Tuvalu. Tuvaluan is of the Ellicean group of Polynesian languages, distantly related to all other Polynesian languages such as Hawaiian, Māori, Tahitian, Rapa Nui, Samoan and Tongan.[255] It is most closely related to the languages spoken on the Polynesian outliers in Micronesia and northern and central Melanesia. The Tuvaluan language has borrowed from the Samoan language, as a consequence of Christian missionaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries being predominantly Samoan.[40][255]

The Tuvaluan language is spoken by virtually everyone, while a Micronesian language very similar to Gilbertese is spoken on Nui.[255][256] English is also an official language but is not spoken in daily use. Parliament and official functions are conducted in the Tuvaluan language.

There are about 13,000 Tuvaluan speakers worldwide.[257][258] Radio Tuvalu transmits Tuvaluan-language programming.[259][260][261]

Religion

[edit]

The Congregational Christian Church of Tuvalu, which is part of the Calvinist tradition, is the state church of Tuvalu;[262] although in practice this merely entitles it to "the privilege of performing special services on major national events".[263] Its adherents comprise about 86% of the 10,632 (2022 census) inhabitants of the archipelago.[262][1] The Constitution of Tuvalu guarantees freedom of religion, including the freedom to practice, the freedom to change religion, the right not to receive religious instruction at school or to attend religious ceremonies at school, and the right not to "take an oath or make an affirmation that is contrary to his religion or belief".[264]

Other Christian groups include the Catholic community served by the Mission Sui Iuris of Funafuti (1%), and the Seventh-day Adventist which has 2% of the population.[1] The Tuvalu Brethren Church has 3% of the population.[1]

The Baháʼí Faith is the largest minority religion and the largest non-Christian religion in Tuvalu. It constitutes 1% of the population.[1] The Baháʼís are present on Nanumea,[265] and Funafuti.[266] The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community consists of about 50 members (0.4% of the population).[267]

The introduction of Christianity ended the worship of ancestral spirits and other deities (animism),[268] along with the power of the vaka-atua (the priests of the old religions).[269] Laumua Kofe describes the objects of worship as varying from island to island, although ancestor worship was described by the Rev. Samuel James Whitmee in 1870 as being common practice.[270]

Health

[edit]The Princess Margaret Hospital on Funafuti is the only hospital in Tuvalu and the primary provider of medical services.

Since the late 20th century, the biggest health problems in Tuvalu have been obesity-related. The leading cause of death has been heart disease,[271] which is closely followed by diabetes[272] and high blood pressure.[271] In 2016 the majority of deaths resulted from cardiac diseases, with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, and cerebral-vascular disease among the other causes of death.[273]

Education

[edit]

Education in Tuvalu is free and compulsory between the ages of 6 and 15 years. Each island has a primary school. Motufoua Secondary School is located on Vaitupu.[274] Students board at the school during the school term, returning to their home islands each school vacation. Fetuvalu Secondary School, a day school operated by the Church of Tuvalu, is on Funafuti.[275]

Fetuvalu offers the Cambridge syllabus. Motufoua offers the Fiji Junior Certificate (FJC) at year 10, Tuvaluan Certificate at Year 11 and the Pacific Senior Secondary Certificate (PSSC) at Year 12, which is set by SPBEA, the Fiji-based exam board.[276] Sixth form students who pass their PSSC go on to the Augmented Foundation Programme, funded by the Tuvalu government. This program is required for tertiary education programmes outside of Tuvalu and is available at the University of the South Pacific (USP) Extension Centre in Funafuti.[277]

Required attendance at school is 10 years for males and 11 years for females (2001).[244] The adult literacy rate is 99.0% (2002).[278] In 2010, there were 1,918 students who were taught by 109 teachers (98 certified and 11 uncertified). The teacher-pupil ratio for primary schools in Tuvalu is around 1:18 for all schools with the exception of Nauti School, which has a ratio of 1:27. Nauti School on Funafuti is the largest primary school in Tuvalu with more than 900 students (45 per cent of the total primary school enrolment). The pupil-teacher ratio for Tuvalu is low compared to the entire Pacific region (ratio of 1:29).[279]

Community Training Centres (CTCs) have been established within the primary schools on each atoll. They provide vocational training to students who do not progress beyond Class 8 because they failed the entry qualifications for secondary education. The CTCs offer training in basic carpentry, gardening and farming, sewing and cooking. At the end of their studies the graduates can apply to continue studies either at Motufoua Secondary School or the Tuvalu Maritime Training Institute (TMTI). Adults can also attend courses at the CTCs.[280]

Four tertiary institutions offer technical and vocational courses: Tuvalu Maritime Training Institute (TMTI), Tuvalu Atoll Science Technology Training Institute (TASTII), Australian Pacific Training Coalition (APTC) and University of the South Pacific (USP) Extension Centre.[281]

The Tuvaluan Employment Ordinance of 1966 sets the minimum age for paid employment at 14 years and prohibits children under the age of 15 from performing hazardous work.[282]

Culture

[edit]Architecture

[edit]The traditional buildings of Tuvalu used plants and trees from the native broadleaf forest,[283] including timber from pouka (Hernandia peltata); ngia or ingia bush (Pemphis acidula); miro (Thespesia populnea); Tonga (Rhizophora mucronata); fau or fo fafini, or woman's fibre tree (Hibiscus tiliaceus).[283] Fibre is from coconut; ferra, native fig (Ficus aspem); fala, screw pine or Pandanus.[283] The buildings were constructed without nails, lashed together with plaited sennit rope handmade from dried coconut fibre.[284]

Following contact with Europeans, iron products were used including nails and corrugated roofing material. Modern buildings in Tuvalu are constructed from imported building materials, including imported timber and concrete.[284]

Church and community buildings (maneapa) are usually coated with white paint that is known as lase, which is made by burning a large amount of dead coral with firewood. The whitish powder that is the result is mixed with water and painted on the buildings.[285]

Art

[edit]The women of Tuvalu use cowrie and other shells in traditional handicrafts.[286] The artistic traditions of Tuvalu have traditionally been expressed in the design of clothing and traditional handicrafts such as the decoration of mats and fans.[286] Crochet (kolose) is one of the art forms practised by Tuvaluan women.[287] The design of women's skirts (titi), tops (teuga saka), headbands, armbands, and wristbands, which continue to be used in performances of the traditional dance songs of Tuvalu, represents contemporary Tuvaluan art and design.[288] The material culture of Tuvalu uses traditional design elements in artefacts used in everyday life such as the design of canoes and fish hooks made from traditional materials.[289][290]

In 2015, an exhibition was held on Funafuti of the art of Tuvalu, with works that addressed climate change through the eyes of artists and the display of Kope ote olaga (possessions of life), a display of the various artefacts of Tuvalu culture.[291]

Dance and music

[edit]

The traditional music of Tuvalu consists of a number of dances, including fakaseasea, fakanau and fatele.[292] The fatele, in its modern form, is performed at community events and to celebrate leaders and other prominent individuals, such as the visit of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in September 2012.[293][294] The Tuvaluan style can be described "as a musical microcosm of Polynesia, where contemporary and older styles co-exist".[292]

Cuisine

[edit]The cuisine of Tuvalu is based on the staple of coconut and the many species of fish found in the ocean and lagoons of the atolls. Desserts made on the islands include coconut and coconut milk, rather than animal milk. The traditional foods eaten in Tuvalu are pulaka, taro, bananas, breadfruit[295] and coconut.[296] Tuvaluans also eat seafood, including coconut crab and fish from the lagoon and ocean.[129] Another traditional food source is seabirds (taketake or black noddy and akiaki or white tern), with pork being eaten mostly at fateles (or parties with dancing to celebrate events).[239]

Pulaka is the main source for carbohydrates. Seafood provides protein. Bananas and breadfruit are supplemental crops. Coconut is used for its juice, to make other beverages (such as toddy) and to improve the taste of some dishes.[239]

A 1560-square-metre pond was built in 1996 on Vaitupu to sustain aquaculture in Tuvalu.[297]

Flying fish are also caught as a source of food;[298][299][300] and as an exciting activity, using a boat, a butterfly net and a spotlight to attract the flying fish.[239]

Heritage

[edit]The traditional community system still survives to a large extent on Tuvalu. Each family has its own task, or salanga, to perform for the community, such as fishing, house building or defence. The skills of a family are passed on from parents to children.

Most islands have their own fusi, community-owned shops similar to convenience stores, where canned foods and bags of rice can be purchased. Goods are cheaper, and fusis give better prices for their own produce.[239]

Another important building is the falekaupule or maneapa, the traditional island meeting hall,[301] where important matters are discussed and which is also used for wedding celebrations and community activities such as a fatele involving music, singing and dancing.[239] Falekaupule is also used as the name of the council of elders – the traditional decision-making body on each island. Under the Falekaupule Act, Falekaupule means "traditional assembly in each island ... composed in accordance with the Aganu of each island". Aganu means traditional customs and culture.[301]

Historical records are held by the Tuvalu National Library and Archives. The creation of a Tuvalu National Cultural Centre and Museum was discussed in the government's strategic plan for 2018–24.[302][303]

Traditional single-outrigger canoe

[edit]

Paopao (from the Samoan language, meaning a small fishing-canoe made from a single log), is the traditional single-outrigger canoe of Tuvalu, of which the largest could carry four to six adults. The variations of single-outrigger canoes that had been developed on Vaitupu and Nanumea were reef-type or paddled canoes; that is, they were designed for carrying over the reef and being paddled, rather than being sailed.[289] Outrigger canoes from Nui were constructed with an indirect type of outrigger attachment and the hull is double-ended, with no distinct bow and stern. These canoes were designed to be sailed over the Nui lagoon.[304] The booms of the outrigger are longer than those found in other designs of canoes from the other islands. This made the Nui canoe more stable when used with a sail than the other designs.[304]

Sport and leisure

[edit]A traditional sport played in Tuvalu is kilikiti,[305] which is similar to cricket.[306] A popular sport specific to Tuvalu is Te ano (The ball), which is played with two round balls of 12 cm (5 in) diameter.[239] Te ano is a traditional game that is similar to volleyball, in which the two hard balls made from pandanus leaves are volleyed at great speed with the team members trying to stop the ball hitting the ground.[307] Traditional sports in the late 19th century were foot racing, lance throwing, quarterstaff fencing and wrestling, although the Christian missionaries disapproved of these activities.[308]

The popular sports in Tuvalu include kilikiti, Te ano, association football, futsal, volleyball, handball, basketball and rugby sevens. Tuvalu has sports organisations for athletics, badminton, tennis, table tennis, volleyball, football, basketball, rugby union, weightlifting and powerlifting. At the 2013 Pacific Mini Games, Tuau Lapua Lapua won Tuvalu's first gold medal in an international competition in the weightlifting 62 kilogram male snatch. (He also won bronze in the clean and jerk, and obtained the silver medal overall for the combined event.)[309] In 2015, Telupe Iosefa received the first gold medal won by Tuvalu at the Pacific Games in the powerlifting 120 kg male division.[310][311][312]

Football in Tuvalu is played at club and national team level. The Tuvalu national football team trains at the Tuvalu Sports Ground in Funafuti and competes in the Pacific Games. The Tuvalu National Football Association is an associate member of the Oceania Football Confederation (OFC) and is seeking membership in FIFA.[313][314] The Tuvalu national futsal team participates in the Oceanian Futsal Championship.

A major sporting event is the "Independence Day Sports Festival" held annually on 1 October. The most important sports event within the country is arguably the Tuvalu Games, which are held yearly since 2008. Tuvalu first participated in the Pacific Games in 1978 and in the Commonwealth Games in 1998, when a weightlifter attended the games held at Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.[315] Two table tennis players attended the 2002 Commonwealth Games in Manchester, England;[315] Tuvalu entered competitors in shooting, table tennis and weightlifting at the 2006 Commonwealth Games in Melbourne, Australia;[315] three athletes participated in the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi, India, entering the discus, shot put and weightlifting events;[315] and a team of 3 weightlifters and 2 table tennis players attended the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow. Tuvaluan athletes have also participated in the men's and women's 100 metres sprint at the World Championships in Athletics from 2009.

The Tuvalu Association of Sports and National Olympic Committee (TASNOC) was recognised as a National Olympic Committee in July 2007. Tuvalu entered the Olympic Games for the first time at the 2008 Summer Games in Beijing, China, with a weightlifter and two athletes in the men's and women's 100 metres sprint. A team with athletes in the same events represented Tuvalu at the 2012 Summer Olympics.[316] Etimoni Timuani was the sole representative of Tuvalu at the 2016 Summer Olympics in the 100m event.[317] Karalo Maibuca and Matie Stanley represented Tuvalu at the 2020 Summer Olympics in the 100m events.[318][319] Tuvalu sent a team to the 2023 Pacific Games. Tuvalu was represented in athletic events at the 2024 Summer Olympics by Karalo Maibuca in the men's 100 metres,[320] and Temalini Manatoa in the women's 100 metres.[321]

Economy and government services

[edit]Economy

[edit]

From 1996 to 2002, Tuvalu was one of the best-performing Pacific Island economies and achieved an average real gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of 5.6% per annum. Economic growth slowed after 2002, with GDP growth of 1.5% in 2008. Tuvalu was exposed to rapid rises in world prices of fuel and food in 2008, with the level of inflation peaking at 13.4%.[278] Tuvalu has the smallest total GDP of any sovereign state in the world.[322] Tuvalu joined the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on 24 June 2010.[323]

In 2023, the IMF Article IV consultation with Tuvalu concluded that a successful vaccination strategy allowed Tuvalu to lift coronavirus disease (COVID) containment measures at the end of 2022. However, the economic cost of the pandemic was significant, with real gross domestic product growth falling, and an increase in the rate of inflation.[324] The increase in inflation in 2022 was due to the rapid rise in the cost of food resulting from a drought that affected food production and from rising global food prices, following Russia's invasion of Ukraine (food imports represent 19 percent of Tuvalu's GDP, while agriculture makes up for only 10 percent of GDP).[324]

The growth of GDP of Tuvalu was at a high point in 2019. The global pandemic resulted in a retraction in the level of GDP (-3.7% in 2020, -0.5% in 2021, and -2.3% in 2022). Tuvalu experienced a 7.9% GDP growth in 2023, however the growth was estimated to moderate to 3.3 percent in 2024. An important factor in the moderation in growth is an expected decline in fishing revenue.[325] In 2025, GDP growth was estimated to further moderate to 3 percent of GDP. In 2026, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects GDP growth to ease further to 2.1 percent.[326] This trend towards more modest and sustainable growth levels reflects underlying structural challenges in the economy of Tuvalu, including sluggish productivity, rising emigration, and growing exposure to climate-related risks, and also Tuvalu’s exposure to global economic conditions.[327][325] Tuvalu’s economy is small and heavily reliant on a few sectors, including fishing, government services, and remittances from Tuvaluans participated in regional employment programmes in Australia and New Zealand. The National Bank of Tuvalu calculated remittances from New Zealand and Australia rose to 7% of GDP between 2021 and 2023.[327]

The government is the primary provider of medical services through Princess Margaret Hospital on Funafuti, which operates health clinics on the other islands. Banking services are provided by the National Bank of Tuvalu. Public sector workers make up about 65% of those formally employed. Remittances from Tuvaluans living in Australia and New Zealand, and remittances from Tuvaluan sailors employed on overseas ships are important sources of income for Tuvaluans.[328] Approximately 15% of adult males work as seamen on foreign-flagged merchant ships. Agriculture in Tuvalu is focused on coconut trees and growing pulaka in large pits of composted soil below the water table. Tuvaluans are otherwise involved in traditional subsistence agriculture and fishing.

Tuvaluans are well known for their seafaring skills, with the Tuvalu Maritime Training Institute on Amatuku motu (island), Funafuti, providing training to approximately 120 marine cadets each year so that they have the skills necessary for employment as seafarers on merchant shipping. The Tuvalu Overseas Seamen's Union (TOSU) is the only registered trade union in Tuvalu. It represents workers on foreign ships. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates that 800 Tuvaluan men are trained, certified and active as seafarers. The ADB estimates that, at any one time, about 15% of the adult male population works abroad as seafarers.[329] Job opportunities also exist as observers on tuna boats where the role is to monitor compliance with the boat's tuna fishing licence.[330]

Government revenues largely come from sales of fishing licences, income from the Tuvalu Trust Fund, and from the lease of its ".tv" internet Top Level Domain (TLD). Tuvalu began deriving revenue from the commercialisation of its ".tv" internet domain name,[331] which was managed by Verisign until 2021.[332][333] In 2023, an agreement between the government of Tuvalu and the GoDaddy company, outsourced the marketing, sales, promotion and branding of the .tv domain to the Tuvalu Telecommunications Corporation, which established a .tv unit.[334] Tuvalu also generates income from postage stamps by the Tuvalu Philatelic Bureau, and from the Tuvalu Ship Registry.

The Tuvalu Trust Fund (TTF) was established in 1987 by the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand.[39] The TTF is a sovereign wealth fund that is owned by Tuvalu but is administered by an international board and the government of Tuvalu. When the performance of the TTF exceeds its operating target each year, excess funds are transferred to the Consolidated Investment Fund (CIF), and can be freely drawn upon by the Tuvaluan government to finance budgetary expenditures.[335] In 2022, the value of the Tuvalu Trust Fund is approximately $190 million.[335] In 2021 the market value of the TTF rose by 12 percent to its highest level on record (261 percent of GDP). However, the volatility in global equity markets in 2022 resulted in the TTF's value falling by 7 percent as compared to the end of 2021.[335]

Financial support to Tuvalu is also provided by Japan, South Korea and the European Union. Australia and New Zealand continue to contribute capital to the TTF, and provide other forms of development assistance.[328][39]

The U.S. government is also a major revenue source for Tuvalu. In 1999, the payment from the South Pacific Tuna Treaty (SPTT) was about $9 million, with the value increasing in the following years. In May 2013, representatives from the United States and the Pacific Islands countries agreed to sign interim arrangement documents to extend the Multilateral Fisheries Treaty (which encompasses the South Pacific Tuna Treaty) for 18 months.[336]