Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

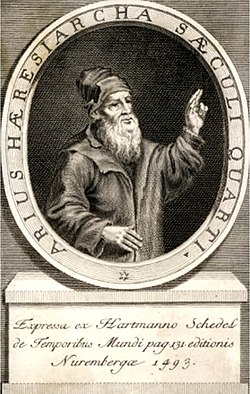

Arius

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Key Information

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Arianism |

|---|

| History and theology |

| Arian leaders |

| Other Arians |

| Modern semi-Arians |

| Opponents |

|

|

Arius (/əˈraɪəs, ˈɛəri-/; Koine Greek: Ἄρειος, romanized: Áreios; 250 or 256 – 336) was a Cyrenaic presbyter and ascetic. He has been regarded as the founder of Arianism,[1][2] which holds that Jesus Christ was not coeternal with God the Father, but was rather created by God the Father. Arian theology and its doctrine regarding the nature of the Godhead showed a belief in radical subordinationism,[3] a view notably disputed by 4th century figures such as Athanasius of Alexandria.[4]

Constantine the Great's formal decriminalization of Christianity into the Roman Empire entailed the convention of ecumenical councils to remove theological divisions between opposing sects within the Church. Arius's theology was a prominent topic at the First Council of Nicaea, where Arianism was condemned in favor of Homoousian conceptions of God and Jesus. Opposition to Arianism remains embodied in the Nicene Creed, described as "a deliberately anti-Arian document."[5] Nevertheless, despite concerted opposition, Arian churches persisted for centuries throughout Europe (especially in various Germanic kingdoms), the Middle East, and North Africa. They were suppressed by military conquest or by voluntary royal conversion between the fifth and seventh centuries.

Arius's role as the sole originator of Arian theology has been disputed by historians such as Rowan Williams, who stated that "Arius' role in 'Arianism' was not that of the founder of a sect. It was not his individual teaching that dominated the mid-century eastern Church."[6] Richard Hanson writes that Arius' specific espousal of subordinationist theology brought "into unavoidable prominence a doctrinal crisis which had gradually been gathering[...] He was the spark that started the explosion. But in himself he was of no great significance."[7] The association between Arius and the theology titled after him has been argued to be a creation "based on the polemic of Nicene writers" such as Athanasius of Alexandria, a Homoousian.[8]

Early life and personality

[edit]Reconstructing the life and doctrine of Arius has proven to be a difficult task.

Arius was of Berber descent.[9] His father's name is given as Ammonius.

Hanson says that "Arius very probably had at some time studied with Lucian of Antioch" because he refers to somebody else as "truly a fellow-disciple of Lucian."[10] But Williams questions whether "we should assume from the one word in Arius' letter that he had actually been Lucian's student."[11]

In the past, many writers have assumed that our Arius is the same as the Arius who was involved in the Melitian schism, "who had an outward appearance of piety, and ... was eager to be a teacher."[12] However, after several pages of detailed analysis, Williams concludes that "the Melitian Arius ... melt(s) away under close investigation."[13]

In 313, Arius was made presbyter of the Baucalis district in Alexandria.

Arius' views have always been "represented as ... some hopelessly defective form of belief."[14] Contrary to this view, Rowan Williams recently concluded that Arius is "a thinker and exegete of resourcefulness, sharpness and originality."[15]

Although his character has been severely assailed by his opponents, Arius appears to have been a man of personal ascetic achievement, pure morals, and decided convictions.

"He was very tall in stature, with downcast countenance ... always garbed in a short cloak and sleeveless tunic; he spoke gently, and people found him persuasive and flattering."[16]

It is traditional to claim that Arius was a deliberate radical, breaking away from the 'orthodoxy' of the church fathers. However:

"A great deal of recent work seeking to understand Arian spirituality has, not surprisingly, helped to demolish the notion of Arius and his supporters as deliberate radicals, attacking a time-honoured tradition."[17] "Arius was a committed theological conservative; more specifically, a conservative Alexandrian."[18]

Arius' writings

[edit]Very little of Arius' writing has survived. "As far as his own writings go, we have no more than three letters, (and) a few fragments of another." The three are:

- The confession of faith Arius presented to Alexander of Alexandria,

- His letter to Eusebius of Nicomedia, and

- The confession he submitted to the emperor."[19]

The letters' original text and English translation can be found in Fontes Nicaenae Synodi.[20]

"The Thalia is Arius' only known theological work"[21] but "we do not possess a single complete and continuous text."[22] We only have extracts from it in the writings of Arius' enemies, "mostly from the pen of Athanasius of Alexandria, his bitterest and most prejudiced enemy."[23]

Emperor Constantine ordered their burning while Arius was still living but R.P.C. Hanson concluded that so little survived because "the people of his day, whether they agreed with him or not, did not regard him (Arius) as a particularly significant writer."[7]

Those works which have survived are quoted in the works of churchmen who denounced him as a heretic. This leads some—but not all—scholars to question their reliability.[24] For example Bishop R.P.C. Hanson wrote:

"Athanasius, a fierce opponent of Arius ... certainly would not have stopped short of misrepresenting what he said."[21] "Athanasius... may be suspected of pressing the words maliciously rather further than Arius intended."[25]

Archbishop Rowan Williams agrees that Athanasius applied "unscrupulous tactics in polemic and struggle."[26]

Arian controversy

[edit]Beginnings

[edit]The Diocletianic Persecution (Great Persecution) of AD 303–313 was Rome's final attempt to limit the expansion of Christianity across the empire. That persecution came to an end when Christianity was legalized with Galerius' Edict of Toleration in 311 followed by Constantine's Edict of Milan in 313, after Emperor Constantine himself had become a Christian. The Arian Controversy began only 5 years later in 318 when Arius, who was in charge of one of the churches in Alexandria, publicly criticized his bishop Alexander for "carelessness in blurring the distinction of nature between the Father and the Son by his emphasis on eternal generation".[27]

The Trinitarian historian Socrates of Constantinople reports that Arius sparked the controversy that bears his name when Alexander of Alexandria, who had succeeded Achillas as the Bishop of Alexandria, gave a sermon stating the similarity of the Son to the Father. Arius interpreted Alexander's speech as being a revival of Sabellianism, condemned it, and then argued that "if the Father begat the Son, he that was begotten had a beginning of existence: and from this it is evident, that there was a time when the Son was not. It therefore necessarily follows, that he [the Son] had his substance from nothing."[28] This quote describes the essence of Arius's doctrine.

Socrates of Constantinople believed that Arius was influenced in his thinking by the teachings of Lucian of Antioch, a celebrated Christian teacher and martyr. In a letter to Patriarch Alexander of Constantinople, Arius's bishop, Alexander of Alexandria, wrote that Arius derived his theology from Lucian. The express purpose of the letter was to complain about the doctrines that Arius was spreading, but his charge of heresy against Arius is vague and unsupported by other authorities. Furthermore, Alexander's language, like that of most controversialists in those days, is quite bitter and abusive. Moreover, even Alexander never accused Lucian of having taught Arianism.

Supporters

[edit]It is traditionally taught that Arius had wide support in the areas of the Roman Empire.

"The Thalia appears ... to have circulated only in Alexandria; what is known of him elsewhere seems to stem from Athanasius' quotations."[29]He also had the support of perhaps the two most important church leaders of that time:

Eusebius of Nicomedia

[edit]Eusebius of Nicomedia "was a supporter of Arius as long as Arius lived."[30] "The conventional picture of Eusebius is of an unscrupulous intriguer."[31] "This is of course because our knowledge of Eusebius derives almost entirely from the evidence of his bitter enemies."[31] Hanson mentions several instances displaying Eusebius' integrity and courage[32] and concludes:

"Eusebius certainly was a man of strong character and great ability" (page 29). "It was he who virtually took charge of the affairs of the Greek speaking Eastern Church from 328 until his death" (page 29). He encouraged the spread of the Christian faith beyond the frontiers of the Roman Empire. The version of the Christian faith which the missionaries spread was that favoured by Eusebius and not Athanasius. This serves as evidence of his zeal."[33]

Eusebius of Caesarea

[edit]"Eusebius, bishop of Caesarea in Palestine [the church historian] was certainly an early supporter of Arius."[34] "He was universally acknowledged to be the most scholarly bishop of his day."[34] "Eusebius of Caesarea ... was one of the most influential authors of the fourth century."[35] "Neither Arius nor anti-Arians speak evil of him."[34] "He was made bishop of Caesarea about 313, (and) attended the Council of Nicaea in 325."[36]

"We cannot accordingly describe Eusebius (of Caesarea) as a formal Arian in the sense that he knew and accepted the full logic of Arius, or of Asterius' position. But undoubtedly, he approached it nearly."[37]

Origen and Arius

[edit]Like many third-century Christian scholars, Arius was influenced by the writings of Origen, widely regarded as the first great theologian of Christianity.[38] However, while both agreed on the subordination of the Son to the Father, and Arius drew support from Origen's theories on the Logos, the two did not agree on everything. For example:

- Hanson refers several times to Origen's teaching that the Son always existed, for example, "Origen's doctrine of the eternal generation of the Son by the Father."[39] To contrast this with what Arius taught, Hanson states that Arius taught that 'there was a time when he did not exist'."[40]

- "Arius in the Thalia sees the Son as praising the Father in heaven; Origen generally avoids language suggesting that the Son worships the Father as God."[41]

Hanson concluded:

"Arius probably inherited some terms and even some ideas from Origen, ... he certainly did not adopt any large or significant part of Origen's theology."[42] "He was not without influence from Origen, but cannot seriously be called an Origenist."[43]

However, because Origen's theological speculations were often proffered to stimulate further inquiry rather than to put an end to any given dispute, both Arius and his opponents were able to invoke the authority of this revered (at the time) theologian during their debate.[44]

Divine but not fully divine

[edit]Arius emphasized the supremacy and uniqueness of God the Father, meaning that the Father alone is infinite and eternal and almighty, and that therefore the Father's divinity must be greater than the Son's. Arius maintained that the Son possessed neither the eternity nor the true divinity of the Father but was rather made "God" only by the Father's permission and power.[45][46]

"Many summary accounts present the Arian controversy as a dispute over whether or not Christ was divine."[47] "It is misleading to assume that these controversies were about 'the divinity of Christ'."[48] "Many fourth-century theologians (including some who were in no way anti-Nicene) made distinctions between being 'God' and being 'true God' that belie any simple account of the controversy in these terms."[49]

"It must be understood that in the fourth century the word 'God' (theos, deus) had not acquired the significance which in our twentieth-century world it has acquired ... viz. the one and sole true God. The word could apply to many gradations of divinity and was not as absolute to Athanasius as it is to us."[50]

Initial responses

[edit]The Bishop of Alexandria exiled the presbyter following a council of local priests. Arius's supporters vehemently protested. Numerous bishops and Christian leaders of the era supported his cause, among them Eusebius of Nicomedia, who baptized Constantine the Great.[51]

First Council of Nicaea

[edit]

The Christological debate could no longer be contained within the Alexandrian diocese. By the time Bishop Alexander finally acted against Arius, Arius's doctrine had spread far beyond his own see; it had become a topic of discussion—and disturbance—for the entire Church. The Church was now a powerful force in the Roman world, with Emperors Licinius and Constantine I having legalized it in 313 through the Edict of Milan. Emperor Constantine had taken a personal interest in several ecumenical issues, including the Donatist controversy in 316, and he wanted to bring an end to the Christological dispute. To this end, the emperor sent Hosius, bishop of Córdoba to investigate and, if possible, resolve the controversy. Hosius was armed with an open letter from the Emperor: "Wherefore let each one of you, showing consideration for the other, listen to the impartial exhortation of your fellow-servant." However, as the debate continued to rage despite Hosius's efforts, Constantine in AD 325 took an unprecedented step: he called a council to be composed of church prelates from all parts of the empire to resolve this issue, possibly at Hosius's recommendation.[52]

"Around 250–300 attended, drawn almost entirely from the eastern half of the empire."[53] Pope Sylvester I, himself too aged to attend, sent two priests as his delegates. Arius himself attended the council, as did his bishop, Alexander. Also there were Eusebius of Caesarea, Eusebius of Nicomedia and the young deacon Athanasius, who would become the champion of the Trinitarian view ultimately adopted by the council and spend most of his life battling Arianism. Before the main conclave convened, Hosius initially met with Alexander and his supporters at Nicomedia.[54] The council was presided over by the emperor himself, who participated in and even led some of its discussions.[52]

At this First Council of Nicaea, 22 bishops, led by Eusebius of Nicomedia, came as supporters of Arius. Nonetheless, when some of Arius's writings were read aloud, they are reported to have been denounced as blasphemous by most participants.[52] Those who upheld the notion that Christ was co-eternal and consubstantial with the Father were led by the bishop Alexander. Athanasius was not allowed to sit in on the Council because he was only an arch-deacon. However, Athanasius is seen as doing the legwork and concluded (according to Bishop Alexander's defense of Athanasian Trinitarianism and also according to the Nicene Creed adopted at this Council)[55][56] that the Son was of the same essence (homoousios) with the Father (or one in essence with the Father), and was eternally generated from that essence of the Father.[57] Those who instead insisted that the Son of God came after God the Father in time and substance were led by Arius the presbyter. For about two months, the two sides argued and debated,[58] with each appealing to Scripture to justify their respective positions. Arius argued for the supremacy of God the Father, and maintained that the Son of God was simply the oldest and most beloved creature of God, made from nothing, because of being the direct offspring. Arius taught that the pre-existent Son was God's first production (the very first thing that God actually ever did in his entire eternal existence up to that point), before all ages. Thus he insisted that only God the Father had no beginning, and that the Father alone was infinite and eternal. Arius maintained that the Son had a beginning. Thus, said Arius, only the Son was directly created and begotten of God; furthermore, there was a time that he had no existence. He was capable of his own free will, said Arius, and thus "were He in the truest sense a son, He must have come after the Father, therefore the time obviously was when He was not, and hence He was a finite being."[59] Arius appealed to Scripture, quoting verses such as John 14:28: "the Father is greater than I",[60] as well as Colossians 1:15: "the firstborn of all creation."[61] Thus, Arius insisted that the Father's Divinity was greater than the Son's, and that the Son was under God the Father, and not co-equal or co-eternal with him.

According to some accounts in the hagiography of Nicholas of Myra, debate at the council became so heated that at one point, Nicholas struck Arius across the face.[62][63] The majority of the bishops ultimately agreed upon a creed, known thereafter as the Nicene Creed. It included the word homoousios, meaning "consubstantial", or "one in essence", which was incompatible with Arius's beliefs.[64] On June 19, 325, council and emperor issued a circular to the churches in and around Alexandria: Arius and two of his unyielding partisans (Theonas and Secundus)[64] were deposed and exiled to Illyricum, while three other supporters—Theognis of Nicaea, Eusebius of Nicomedia and Maris of Chalcedon—affixed their signatures solely out of deference to the emperor. The following is part of the ruling made by the emperor denouncing Arius's teachings with fervor.

In addition, if any writing composed by Arius should be found, it should be handed over to the flames, so that not only will the wickedness of his teaching be obliterated, but nothing will be left even to remind anyone of him. And I hereby make a public order, that if someone should be discovered to have hidden a writing composed by Arius, and not to have immediately brought it forward and destroyed it by fire, his penalty shall be death. As soon as he is discovered in this offense, he shall be submitted for capital punishment [...]

— Edict by Emperor Constantine against the Arians[65]

Exile, return, and death

[edit]The homoousian party's victory at Nicaea was short-lived, however. Despite Arius' exile and the ostensible finality of the Council's decrees, the Arian controversy recommenced at once. When Bishop Alexander died in 327, Athanasius succeeded him, despite not meeting the age requirements for a hierarch. Still committed to pacifying the conflict between Arians and Trinitarians, Constantine gradually became more lenient toward those whom the Council of Nicaea had exiled.[52] Though he never repudiated the council or its decrees, the emperor ultimately permitted Arius (who had taken refuge in Palestine) and many of his adherents to return to their homes, once Arius had reformulated his Christology to mute the ideas found most objectionable by his critics. Athanasius was exiled following his condemnation by the First Synod of Tyre in 335 (though he was later recalled), and the Synod of Jerusalem the following year restored Arius to communion. The emperor directed Alexander of Constantinople to receive Arius, despite the bishop's objections; Bishop Alexander responded by earnestly praying that Arius might perish before this could happen.[66]

Modern scholars consider that the subsequent death of Arius may have been the result of poisoning by his opponents.[67][68] In contrast, some contemporaries of Arius asserted that the circumstances of his death were a miraculous consequence of Arius's heretical views. The latter view was evident in the account of Arius's death by a bitter enemy, Socrates Scholasticus:

It was then Saturday, and Arius was expecting to assemble with the church on the day following: but divine retribution overtook his daring criminalities. For going out of the imperial palace, attended by a crowd of Eusebian partisans like guards, he paraded proudly through the midst of the city, attracting the notice of all the people. As he approached the place called Constantine's Forum, where the column of porphyry is erected, a terror arising from the remorse of conscience seized Arius, and with the terror a violent relaxation of the bowels: he therefore enquired whether there was a convenient place near, and being directed to the back of Constantine's Forum, he hastened thither. Soon after a faintness came over him, and together with the evacuations his bowels protruded, followed by a copious hemorrhage, and the descent of the smaller intestines: moreover portions of his spleen and liver were brought off in the effusion of blood, so that he almost immediately died. The scene of this catastrophe still is shown at Constantinople, as I have said, behind the shambles in the colonnade: and by persons going by pointing the finger at the place, there is a perpetual remembrance preserved of this extraordinary kind of death.[69]

The death of Arius did not end the Arian controversy, which would not be settled for centuries in some parts of the Christian world.

Arianism after Arius

[edit]Immediate aftermath

[edit]Historians report that Constantine, who had not been baptized for most of his lifetime, was baptized on his deathbed in 337 by the Arian bishop, Eusebius of Nicomedia.[52][70]

Constantius II, who succeeded Constantine, was an Arian sympathizer.[71] Under him, Arianism reached its high point at the Third Council of Sirmium in 357. The Seventh Arian Confession (Second Sirmium Confession) held, regarding the doctrines homoousios (of one substance) and homoiousios (of similar substance), that both were non-biblical; and that the Father is greater than the Son, a confession later dubbed the Blasphemy of Sirmium:

But since many persons are disturbed by questions concerning what is called in Latin substantia, but in Greek ousia, that is, to make it understood more exactly, as to 'coessential', or what is called, 'like-in-essence', there ought to be no mention of any of these at all, nor exposition of them in the Church, for this reason and for this consideration, that in divine Scripture nothing is written about them, and that they are above men's knowledge and above men's understanding.[72]

Following the abortive effort by Julian the Apostate to restore paganism in the empire, emperor Valens—himself an Arian—renewed the persecution of Nicene bishops. However, Valens's successor Theodosius I ended Arianism once and for all among the elites of the Eastern Empire through a combination of imperial decree, persecution, and the calling of the First Council of Constantinople in 381 that condemned Arius anew while reaffirming and expanding the Nicene Creed.[71][73][page needed] This generally ended the influence of Arianism among the non-Germanic peoples of the Roman Empire.

Arianism in the West

[edit]

Arianism played out very differently in the Western Empire; during the reign of Constantius II, the Arian Gothic convert Ulfilas was consecrated a bishop by Eusebius of Nicomedia and sent to missionize his people. His success ensured the survival of Arianism among the Goths and Vandals until the beginning of the eighth century, when their kingdoms succumbed to the adjacent Niceans or they accepted Nicean Christianity. Arians continued to exist in North Africa, Spain and portions of Italy until they were finally suppressed during the sixth and seventh centuries.[74]

In the 12th century, the Benedictine abbot Peter the Venerable described the Islamic prophet Muhammad as "the successor of Arius and the precursor to the Antichrist".[75] During the Protestant Reformation, a Polish sect known as the Polish Brethren were often referred to as Arians due to their antitrinitarian doctrine.[76]

Contemporary Arianism

[edit]There are several contemporary Christian and Post-Christian denominations today that echo Arian thinking.

Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) are sometimes accused of being Arians by their detractors.[77] However, the Christology of the Latter-day Saints differs in several significant aspects from Arian theology.[78]

The Jehovah's Witnesses teach that the Son is a created being, and is not actually God, but rather his only-begotten Son.

Some Christians in the Unitarian Universalist movement are influenced by Arian ideas. Contemporary Unitarian Universalist Christians often may be either Arian or Socinian in their Christology, seeing Jesus as a distinctive moral figure but not equal or eternal with God the Father; or they may follow Origen's logic of Universal Salvation, and thus potentially affirm the Trinity, but assert that all are already saved.

According to the reincarnationist religion of Spiritism, Jesus, the highest-order spirit that has ever incarnated on Earth, is distinct from God, by whom he was created. Jesus is not considered God or part of God as in Nicene Christianity, but nonetheless the ultimate model of human love, intelligence, and forgiveness, often cited as the governor of Earth.

Arius's doctrine

[edit]Introduction

[edit]In explaining his actions against Arius, Alexander of Alexandria wrote a letter to Alexander of Constantinople and Eusebius of Nicomedia (where the emperor was then residing), detailing the errors into which he believed Arius had fallen. According to Alexander, Arius taught:

That God was not always the Father, but that there was a period when he was not the Father; that the Word of God was not from eternity, but was made out of nothing; for that the ever-existing God ('the I AM'—the eternal One) made him who did not previously exist, out of nothing; wherefore there was a time when he did not exist, inasmuch as the Son is a creature and a work. That he is neither like the Father as it regards his essence, nor is by nature either the Father's true Word, or true Wisdom, but indeed one of his works and creatures, being erroneously called Word and Wisdom, since he was himself made of God's own Word and the Wisdom which is in God, whereby God both made all things and him also. Wherefore he is as to his nature mutable and susceptible of change, as all other rational creatures are: hence the Word is alien to and other than the essence of God; and the Father is inexplicable by the Son, and invisible to him, for neither does the Word perfectly and accurately know the Father, neither can he distinctly see him. The Son knows not the nature of his own essence: for he was made on our account, in order that God might create us by him, as by an instrument; nor would he ever have existed, unless God had wished to create us.

— Socrates Scholasticus (Trinitarian)[79]

Alexander also refers to Arius's poetical Thalia:

God has not always been Father; there was a moment when he was alone, and was not yet Father: later he became so. The Son is not from eternity; he came from nothing.

— Alexander (Trinitarian)[80]

Eusebius of Caesarea, in his famous book The Ecclesiastical History explains Arius' views as:[81]

That God has not always been a Father, and that there was a time when the Son was not ; that the Son is a creature like the others ; that he is mutable by his nature; that by his free will he chose to remain virtuous, but that he might change like others. He said that Jesus Christ was not true God, but divine by participation, like all others to whom the name of God is attributed. He added, that he was not the substantial Word of the Father, and his proper wisdom, by which he had made all things, but that he was himself made by the eternal wisdom ; that he is foreign in every thing from the substance of the Father; that we were not made for him, but he for us, when it was the pleasure of God, who was before alone, to create us that he was made by the will of God, as others are, having no previous existence at all, since he is not a proper and natural production of the Father, but an effect of his grace. The father, he continued, is invisible to the Son, and the Son cannot know him perfectly ; nor, indeed, can he know his own substance.

The Logos

[edit]The question of the exact relationship between the Father and the Son (a part of the theological science of Christology) had been raised some fifty years before Arius, when Paul of Samosata was deposed in 269 for agreeing with those who used the word homoousios (Greek for 'same substance') to express the relation between the Father and the Son. This term was thought at that time to have a Sabellian tendency,[82] though—as events showed—this was on account of its scope not having been satisfactorily defined. In the discussion which followed Paul's deposition, Dionysius, the Bishop of Alexandria, used much the same language as Arius did later, and correspondence survives in which Pope Dionysius blames him for using such terminology. Dionysius responded with an explanation widely interpreted as vacillating. The Synod of Antioch, which condemned Paul of Samosata, had expressed its disapproval of the word homoousios in one sense, while Bishop Alexander undertook its defense in another. Although the controversy seemed to be leaning toward the opinions later championed by Arius, no firm decision had been made on the subject; in an atmosphere so intellectual as that of Alexandria, the debate seemed bound to resurface—and even intensify—at some point in the future.

Arius endorsed the following doctrines about the Son or the Word (Logos, referring to Jesus:

- that the Word (Logos) and the Father were not of the same essence (ousia);

- that the Son was a created being (ktisma or poiema); and

- that the worlds were created through him, so he must have existed before them and before all time.

- However, there was a "once" [Arius did not use words meaning 'time', such as chronos or aion] when he did not exist, before he was begotten of the Father.

Extant writings

[edit]Three surviving letters attributed to Arius are his letter to Alexander of Alexandria,[83] his letter to Eusebius of Nicomedia,[84] and his confession to Constantine.[85] In addition, several letters addressed by others to Arius survive, together with brief quotations contained within the polemical works of his opponents. These quotations are often short and taken out of context, and it is difficult to tell how accurately they quote him or represent his true thinking.

The Thalia

[edit]Arius's Thalia (literally, 'festivity', 'banquet'), a popularized work combining prose and verse and summarizing his views on the Logos,[86] survives in quoted fragmentary form. In the Thalia, Arius says that God's first thought was the creation of the Son, before all ages, therefore time started with the creation of the Logos or Word in Heaven (lines 1–9, 30–32). Arius explains how the Son could still be God, even if he did not exist eternally (lines 20–23); and endeavors to explain the ultimate incomprehensibility of the Father to the Son (lines 33–39). The two available references from this work are recorded by his opponent Athanasius: the first is a report of Arius's teaching in Orations Against the Arians, 1:5–6. This paraphrase has negative comments interspersed throughout, so it is difficult to consider it as being completely reliable.[87]

The second quotation appears on page 15 of the document On the Councils of Arminum and Seleucia, also known as De Synodis. This second passage, entirely in irregular verse, seems to be a direct quotation or a compilation of quotations;[88] it may have been written by someone other than Athanasius, perhaps even a person sympathetic to Arius.[89] This second quotation does not contain several statements usually attributed to Arius by his opponents, is in metrical form, and resembles other passages that have been attributed to Arius. It also contains some positive statements about the Son.[90] But although these quotations seem reasonably accurate, their proper context is lost, so their place in Arius's larger system of thought is impossible to reconstruct.[88]

The part of Arius's Thalia quoted in Athanasius's De Synodis is the longest extant fragment. The most commonly cited edition of De Synodis is by Hans-Georg Opitz.[91] A translation of this fragment has been made by Aaron J. West,[92] but based not on Opitz' text but on a previous edition: "When compared to Opitz' more recent edition of the text, we found that our text varies only in punctuation, capitalization, and one variant reading (χρόνῳ for χρόνοις, line 5)."[93] The Opitz edition with the West translation is as follows:

Αὐτὸς γοῦν ὁ θεὸς καθό ἐστιν ἄρρητος ἅπασιν ὑπάρχει.

ἴσον οὐδὲ ὅμοιον, οὐχ ὁμόδοξον ἔχει μόνος οὗτος.

ἀγέννητον δὲ αὐτόν φαμεν διὰ τὸν τὴν φύσιν γεννητόν·

τοῦτον ἄναρχον ἀνυμνοῦμεν διὰ τὸν ἀρχὴν ἔχοντα,

ἀίδιον δὲ αὐτὸν σέβομεν διὰ τὸν ἐν χρόνοις γεγαότα.

ἀρχὴν τὸν υἰὸν ἔθηκε τῶν γενητῶν ὁ ἄναρχος

καὶ ἤνεγκεν εἰς υἱὸν ἑαυτῷ τόνδε τεκνοποιήσας,

ἴδιον οὐδὲν ἔχει τοῦ θεοῦ καθ᾽¦ ὑπόστασιν ἰδιότητος,

οὐδὲ γάρ ἐστιν ἴσος, ἀλλ' οὐδὲ ὁμοούσιος αὐτῷ.

σοφὸς δέ ἐστιν ὁ θεός, ὅτι τῆς σοφίας διδάσκαλος αύτός.

ἱκανὴ δὲ ἀπόδειξις ὅτι ὁ θεὸς ἀόρατος ἅπασι,

τοῖς τε διὰ υἱοῦ καὶ αὐτῷ τῷ υἱῷ ἀόρατος ὁ αὐτός.

ῥητῶς δὲ λέχω, πῶς τῷ υἱῷ ὁρᾶται ὁ ἀόρατος·

τῇ δυνάμει ᾗ δύναται ὁ θεὸς ἰδεῖν· ἰδίοις τε μέτροις

ὑπομένει ὁ υἱὸς ἰδεῖν τὸν πατέρα, ὡς θέμις ἐστίν.

ἤγουν τριάς ἐστι δόξαις οὐχ ὁμοίαις, ἀνεπίμικτοι ἑαυταῖς εἰσιν αἱ ὑποστάσεις αὐτῶν,

μία τῆς μιᾶς ἐνδοξοτέρα δόξαις ἐπ' ἄπειρον.

ξένος τοῦ υἱοῦ κατ' οὐσίαν ὁ πατήρ, ὅτι ἄναρχος ὐπάρχει.

σύνες ὅτι ἡ μονὰς ἦν, ἡ δυὰς δὲ οὐκ ἦν, πρὶν ὑπάρξῃ.

αὐτίκα γοῦν υἱοῦ μὴ ὄντος ὁ πατὴρ θεός ἐστι.

λοιπὸν ὁ υἰὸς οὐκ ὢν (ὐπῆρξε δὲ θελήσει πατρῴᾳ)

μονογενὴς θεός ἐστι καὶ ἑκατέρων ἀλλότριος οὗτος.

ἡ σοφία σοφία ὑπῆρξε σοφοῦ θεοῦ θελήσει.

επινοεῖται γοῦν μυρίαις ὅσαις ἐπινοίαις πνεῦμα, δύναμις, σοφία,

δόξα θεοῦ, ἀλήθειά τε καὶ εἰκὼν καὶ λόγος οὗτος.

σύνες ὅτι καὶ ἀπαύγασμα καὶ φῶς ἐπινοεῖται.

ἴσον μὲν τοῦ υἱοῦ γεννᾶν δυνατός ἐστιν ὁ κρείττων,

διαφορώτερον δὲ ἢ κρείττονα ἢ μείζονα οὐχί.

θεοῦ ¦ θελήσει ὁ υἱὸς ἡλίκος καὶ ὅσος ἐστίν,

ἐξ ὅτε καὶ ἀφ' οὖ καὶ ἀπὸ τότε ἐκ τοῦ θεοῦ ὑπέστη,

ἰσχυρὸς θεὸς ὢν τὸν κρείττονα ἐκ μέρους ὑμνεῖ.

συνελόντι εἰπεῖν τῷ υἱῷ ὁ θεὀς ἄρρητος ὑπάρχει·

ἔστι γὰρ ἑαυτῷ ὅ ἐστι τοῦτ' ἔστιν ἄλεκτος,

ὥστε οὐδὲν τῶν λεγομένων κατά τε κατάληψιν συνίει ἐξειπεῖν ὁ υἱός.

ἀδύνατα γὰρ αὐτῷ τὸν πατέρα τε ἐξιχνιάσει, ὅς ἐστιν ἐφ' ἑαυτοῦ.

αὐτὸς γὰρ ὁ υἱὸς τὴν ἑαυτοῦ οὐσίαν οὐκ οἶδεν,

υἱὸς γὰρ ὢν θελήσει πατρὸς ὑπῆρξεν ἀληθῶς.

τίς γοῦν λόγος συγχωρεῖ τὸν ἐκ πατρὸς ὄντα

αὐτὸν τὸν γεννήσαντα γνῶναι ἐν καταλήψει;

δῆλον γὰρ ὅτι τὸ αρχὴν ἔχον, τὸν ἄναρχον, ὡς ἔστιν,

ἐμπερινοῆσαι ἢ ἐμπεριδράξασθαι οὐχ οἷόν τέ ἐστιν.

... And so God Himself, as he really is, is inexpressible to all.

He alone has no equal, no one similar, and no one of the same glory.

We call him unbegotten, in contrast to him who by nature is begotten.

We praise him as without beginning in contrast to him who has a beginning.

We worship him as timeless, in contrast to him who in time has come to exist.

He who is without beginning made the Son a beginning of created things

He produced him as a son for himself by begetting him.

He [the son] has none of the distinct characteristics of God's own being

For he is not equal to, nor is he of the same being as him.

God is wise, for he himself is the teacher of Wisdom

Sufficient proof that God is invisible to all:

He is invisible both to things which were made through the Son, and also to the Son himself.

I will say specifically how the invisible is seen by the Son:

by that power by which God is able to see, each according to his own measure,

the Son can bear to see the Father, as is determined

So there is a Triad, not in equal glories. Their beings are not mixed together among themselves.

As far as their glories, one infinitely more glorious than the other.

The Father in his essence is a foreigner to the Son, because he exists without beginning.

Understand that the Monad [eternally] was; but the Dyad was not before it came into existence.

It immediately follows that, although the Son did not exist, the Father was still God.

Hence the Son, not being [eternal] came into existence by the Father's will,

He is the Only-begotten God, and this one is alien from [all] others

Wisdom came to be Wisdom by the will of the Wise God.

Hence he is conceived in innumerable aspects. He is Spirit, Power, Wisdom,

God's glory, Truth, Image, and Word.

Understand that he is also conceived of as Radiance and Light.

The one who is superior is able to beget one equal to the Son,

But not someone more important, or superior, or greater.

At God's will the Son has the greatness and qualities that he has.

His existence from when and from whom and from then – are all from God.

He, though strong God, praises in part his superior.

In brief, God is inexpressible to the Son.

For he is in himself what he is, that is, indescribable,

So that the son does not comprehend any of these things or have the understanding to explain them.

For it is impossible for him to fathom the Father, who is by himself.

For the Son himself does not even know his own essence,

For being Son, his existence is most certainly at the will of the Father.

What reasoning allows, that he who is from the Father

should comprehend and know his own parent?

For clearly that which has a beginning

is not able to conceive of or grasp the existence of that which has no beginning.

A slightly different edition of the fragment of the Thalia from De Synodis is given by G.C. Stead,[94] and served as the basis for a translation by R.P.C. Hanson.[95] Stead argued that the Thalia was written in anapestic meter, and edited the fragment to show what it would look like in anapests with different line-breaks. Hanson based his translation of this fragment directly on Stead's text.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Torkington 2011, p. 113.

- ^ Anatolios 2011, p. 44, "Arius, who was born in Libya, was a respected ascetic and presbyter at the church of the Baucalis in Alexandria and was the founder of Arianism.".

- ^ Williams 2002, p. 98.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. xix.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 164.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 165.

- ^ a b Hanson 1988, p. xvii.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 82.

- ^ Hendrix, Scott E.; Okeja, Uchenna (2018-03-01). The World's Greatest Religious Leaders [2 volumes]: How Religious Figures Helped Shape World History [2 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA (published 2018). p. 35. ISBN 978-1-4408-4138-5. Archived from the original on 2023-12-01. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 5.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 30.

- ^ Williams 2004, pp. 34, 32–40.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 40.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 2.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 116.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 175.

- ^ Hanson 1988, pp. 5–6.

- ^ S. Fernández (ed.), Fontes Nicaenae Synodi: the contemporary sources for the study of the Council of Nicaea (304-337), Brill 2024.

- ^ a b Hanson 1988, p. 10.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 62.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 6.

- ^ Dennison, James T Jr. "Arius "Orthodoxos"; Athanasius "Politicus": The Rehabilitation of Arius and the Denigration of Athanasius". Lynnwood: Northwest Theological Seminary. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 15.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 238.

- ^ Lyman, J. Rebecca (2010). "The Invention of 'Heresy' and 'Schism'". The Cambridge History of Christianity.

- ^ Socrates. "The Dispute of Arius with Alexander, his Bishop.". The Ecclesiastical Histories of Socrates Scholasticus. Archived from the original on 10 January 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Ayres 2004, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Hanson 1988, pp. 30, 31.

- ^ a b Hanson 1988, p. 27.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 28.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Hanson 1988, p. 46.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 860.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 47.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 59.

- ^ Moore, Edward (2 May 2005). "Origen of Alexandria". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The University of Tennessee at Martin. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 65.

- ^ Hanson 1988, pp. 65, 86.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 144.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 70.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 98.

- ^ "Arius of Alexandria, Priest and Martyr". Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church (Arian Catholic). Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Kelly 1978, Chapter 9

- ^ Davis 1983, pp. 52–54

- ^ Ayres 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Ayres 2004, pp. 14.

- ^ Ayres 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Hanson 1988, p. 456.

- ^ Rubenstein 2000, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e Vasiliev, Al (1928). "The empire from Constantine the Great to Justinian". History of the Byzantine Empire. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Ayres 2004, p. 19.

- ^ Photius. "Epitome of Chapter VII". Epitome of Book I. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Athanasius, Discourse 1 Against the Arians, part 9, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/28161.htm Archived 2016-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Athanasius, De Decretis, parts 20 and 30, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/2809.htm Archived 2023-07-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Matt Perry – Athanasius and his Influence at the Council of Nicaea Archived 2014-04-07 at the Wayback Machine – QUODLIBET JOURNAL – Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society 1963, p. 477.

- ^ McClintock & Strong 1982, p. 45.

- ^ John 14:28

- ^ Colossians 1:15

- ^ Bishop Nicholas Loses His Cool at the Council of Nicaea Archived 2011-01-01 at the Wayback Machine. From the St. Nicholas center. See also St. Nicholas the Wonderworker Archived 2012-09-10 at the Wayback Machine, from the website of the Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ^ SOCKEY, DARIA (5 December 2012). "In this corner, St. Nicholas!". Catholic Exchange. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- ^ a b Carroll 1987, p. 12.

- ^ Athanasius (23 January 2010). "Edict by Emperor Constantine against the Arians". Fourth Century Christianity. Wisconsin Lutheran College. Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Draper, John William (1875). The History of the Intellectual Development of Europe. pp. 358–359., quoted in "The events following the Council of Nicaea". The Formulation of the Trinity. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Kirsch 2004, p. 178.

- ^ Freeman 2005, p. 171.

- ^ Socrates. "The Death of Arius". The Ecclesiastical Histories of Socrates Scholasticus. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Scrum, D S. "Arian Reaction – Athanasius". Biography of Arius. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ a b Jones 1986, p. 118.

- ^ "Second Creed of Sirmium or "The Blasphemy of Sirmium"". Fourth Century Christianity. Archived from the original on 2017-03-12. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

- ^ Freeman 2009.

- ^ "Arianism". The Columbia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Kritzeck, James (2015) [1964]. Peter the Venerable and Islam. Princeton Studies on the Near East. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 145–146. ISBN 9780691624907.

- ^ Wilbur, Earl Morse (1977). "The Socinian Exiles in East Prussia". A History of Unitarianism in Transylvania, England, and America. Boston: Beacon Press. Archived from the original on 2012-03-03. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- ^ Tuttle, Dainel S (1981). "Mormons". A Religious Encyclopedia: 1578. Archived from the original on 2013-11-07. Retrieved 2010-02-03.

- ^ "Are Mormons Arians?". Mormon Metaphics. 19 January 2006. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Socrates. "Division begins in the Church from this Controversy; and Alexander Bishop of Alexandria excommunicates Arius and his Adherents.". The Ecclesiastical Histories of Socrates Scholasticus. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Carroll 1987, p. 10.

- ^ Eusebius of Caesarea. The Church History (PDF). Bell & Daldy. p. 501. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-05-17. Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- ^ Saint Athanasius 1911, p. 124, footnote.

- ^ Preserved by Athanasius, On the Councils of Arminum and Seleucia, 16; Epiphanius, Refutation of All Heresies, 69.7; and Hilary, On the Trinity, 4.12)

- ^ Recorded by Epiphanius, Refutation of All Heresies, 69.6 and Theodoret, Church History, 1.5

- ^ Recorded in Socrates Scholasticus, Church History 1.26.2 and Sozomen, Church History 2.27.6–10

- ^ Arius. "Thalia". Fourth Century Christianity. Wisconsin Lutheran College. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Williams 2002, p. 99.

- ^ a b Williams 2002, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Hanson 2007, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Stevenson, J (1987). A New Eusebius. London: SPCK. pp. 330–332. ISBN 0-281-04268-3.

- ^ Opitz, Hans-Georg (1935). Athanasius Werke. pp. 242–243. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ West, Aaron J. "Arius – Thalia". Fourth Century Christianity. Wisconsin Lutheran College. Archived from the original on 2012-04-28.

- ^ West, Aaron J. "Arius – Thalia in Greek and English". Fourth Century Christianity. Wisconsin Lutheran College. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ Stead 1978, pp. 48–50.

- ^ Hanson 1988, pp. 14–15.

Works cited

[edit]- "Babylon the Great Has Fallen!" God's Kingdom Rules!. Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society. January 1, 1963. ISBN 0854830138.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - The Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 2 (International ed.). Grolier Academic Reference. December 1997. ISBN 9780717201297.

- Saint Athanasius (1911). Select Treatises of St. Athanasius in Controversy with the Arians. Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Anatolios, Khaled (October 2011). Retrieving Nicaea: The Development and Meaning of Trinitarian Doctrine. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-3132-8.

- Ayres, Lewis (2004). Nicaea and its Legacy, An Approach to Fourth-Century Trinitarian Theology.

- Carroll, Warren H. (1987). A History of Christendom: The Building of Christendom. Christendom college Press. ISBN 0317604929.

- Davis, Leo Donald (1983). The first seven ecumenical councils (325-787) : their history and theology. Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5616-7.

- Freeman, Charles (2005). The Closing of the Western Mind (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 1-4000-3380-2.

- Freeman, Charles (5 February 2009). A.D. 381: Heretics, Pagans, and the Christian State. Abrams. ISBN 978-1-59020-522-8.

- Hanson, Richard Patrick Crosland (1988). The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God: The Arian Controversy, 318-381. T. & T. Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-09485-8.

- Hanson, Richard Patrick Crosland (2007). The Search for the Christian Doctrine of God: The Arian Controversy, 318-381. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-3146-5.

- Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin (1986). The later Roman Empire, 284-602 : a social economic and administrative survey. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-3284-0.

- Kelly, J. N. D. (1978). Early Christian doctrines. San Francisco: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-064334-8.

- Kirsch, Jonathan (2004). God against the gods : the history of the war between monotheism and polytheism. New York: Viking Compass. ISBN 978-0-9659167-7-6.

- McClintock, John; Strong, James (1982). Cyclopedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature: New - Pes. Vol. 7 (2nd ed.). Baker Academic. ISBN 0801061237.

- O'Carroll, Michael (1987). Trinitas. Collegeville: Liturgical Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-8146-5595-5.

- Rubenstein, Richard E. (2000). When Jesus Became God: The Struggle to Define Christianity During the Last Days of Rome. Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-15-601315-4.

- Stead, G. C. (1978). "The "Thalia" of Arius and the Testimony of Athanasius". The Journal of Theological Studies. 29 (1): 20–52. doi:10.1093/jts/XXIX.1.20. ISSN 0022-5185. JSTOR 23960253.

- Torkington, David (3 February 2011). Wisdom from Franciscan Italy: The Primacy of Love. John Hunt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84694-442-0.

- Williams, Rowan (24 January 2002) [1987]. Arius: Heresy and Tradition (Revised ed.). Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-4969-4.

- Williams, Rowan (2004). Arius: Heresy and Tradition. Eerdmans Publishing.

Sources

[edit]Primary sources

[edit]- Athanasius of Alexandria. History of the Arians. Fig. ISBN 978-1-62630-030-9.

- Athanasius of Alexandria. History of the Arians. Online at CCEL. Part I Part II Part III Part IV Part V Part VI Part VII Part VIII. Accessed 13 December 2009.

- Schaff, Philip; Wallace, Henry, eds. (1 June 2007). Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Second Series Volume II Socrates, Sozomenus: Church Histories. New York: Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60206-510-9.

- Sozomen, Hermias. Edward Walford, Translator. The Ecclesiastical History of Sozomen. Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing, 2018. Online at newadvent.org

Secondary sources

[edit]- Latinovic, Vladimir. Arius Conservativus? The Question of Arius' Theological Belonging in: Studia Patristica, XCV, p. 27-42. Peeters, 2017. Online at [1].

- Parvis, Sara. Marcellus of Ancyra And the Lost Years of the Arian Controversy 325–345. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Rusch, William C. The Trinitarian Controversy. Sources of Early Christian Thought, 1980. ISBN 0-8006-1410-0

- Schaff, Philip. "Theological Controversies and the Development of Orthodoxy". In History of the Christian Church, Vol III, Ch. IX. Online at CCEL. Accessed 13 December 2009.

- Wace, Henry. A Dictionary of Christian Biography and Literature to the End of the Sixth Century A.D., with an Account of the Principal Sects a.d Heresies. Online at CCEL. Accessed 13 December 2009.

External links

[edit] Media related to Arius at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Arius at Wikimedia Commons- The Complete Extant Works of Arius From the Wisconsin Lutheran College website page entitled "Fourth Century Christianity".

- Tulloch, John (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. II (9th ed.). pp. 537–538.

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- Works by Arius at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)