Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lower Chitral District

View on Wikipedia

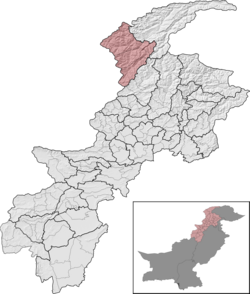

Lower Chitral District (Khowar: موڑی ݯھیترارو ضلع; Urdu: ضلع چترال زیریں) is a district in Malakand Division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in Pakistan. It is mainly populated by the ethnic Kho people.[4]

Key Information

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1961 | 54,844 | — |

| 1972 | 87,617 | +4.35% |

| 1981 | 121,641 | +3.71% |

| 1998 | 184,874 | +2.49% |

| 2017 | 278,328 | +2.18% |

| 2023 | 320,407 | +2.37% |

| Sources:[5] | ||

As of the 2023 census, Lower Chitral district has 46,028 households and a population of 320,407. The district has a sex ratio of 104.31 males to 100 females and a literacy rate of 66.10%: 76.81% for males and 54.77% for females. 87,378 (27.46% of the surveyed population) are under 10 years of age. 57,157 (17.84%) live in urban areas.[2]

87.76% of the population speaks languages classified as 'Others', namely Khowar (or Chitrali), the dominant language of Chitral as a whole. Pashto is spoken in the southeast of the district by 9.36% of the population, while Kalasha is spoken by 1.59% of the population.[6] There are some speakers of the Madaklasht dialect, a Persian dialect which is considered a mix of Dari and Tajik.[7]

Ethnic groups

[edit]The main ethnic groups in the district are:

Religion

[edit]| Religion | 1998[11] | 2017[12] | 2023[13] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Islam |

182,169 | 98.54% | 274,426 | 98.60% | 313,101 | 98.39% |

| Kalash | 2,602 | 1.41% | 3,725 | 1.34% | 4,617 | 1.45% |

| Christianity |

50 | 0.03% | 165 | 0.06% | 509 | 0.16% |

| Hinduism |

2 | 0.00% | 9 | 0.00% | 4 | 0.00% |

| Ahmadi | 51 | 0.03% | 3 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.00% |

| Total | 184,874 | 100.00% | 278,328 | 100.00% | 318,234 | 100.00% |

Administrative Divisions

[edit]| Tehsil | Area

(km²)[14] |

Pop.

(2023) |

Density

(ppl/km²) (2023) |

Literacy rate

(2023)[15] |

Union Councils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitral Tehsil | 6,127 | 211,374 | 34.5 | 70.20% | |

| Drosh Tehsil | 331 | 109,033 | 329.4 | 57.38% |

National Assembly

[edit]The district along with Upper Chitral District is represented by one elected MNA (Member of National Assembly) in Pakistan National Assembly. Its constituency is NA-1.

| Member of National Assembly | Party Affiliation | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Abdul Latif | PTI | 2024 |

Provincial Assembly

[edit]The district is represented by one elected MPA (Member of Provincial Assembly) in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Assembly. Its constituency is PK-2.

| Member of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Assembly | Party Affiliation | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Fateh-ul-Mulk Ali Nasir | PTI | 2024 |

References

[edit]- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 January 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "7th Population and Housing Census - Detailed Results: Table 1" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "Literacy rate, enrolments, and out-of-school population by sex and rural/urban, CENSUS-2023, KPK" (PDF).

- ^ "Upper Chitral gets status of separate district". dawn.com. 21 November 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ "Population by administrative units 1951-1998" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "7th Population and Housing Census - Detailed Results: Table 11" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "Madaklasht village of Ismaili Muslims sets an example of communal tolerance, harmony". 9 June 2014.

- ^ a b "About". www.lowerchitral.kp.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 23 May 2025. Retrieved 19 July 2025.

- ^ Khan, Mohammad Afzal (1975). Chitral and Kafiristan: A Personal Study. Ferozsons. p. 86.

The Gujars who are found in Golen and Shishikuh valley in lower Chitral.

- ^ "Introduction". lowerchitral.kp.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 23 May 2025. Retrieved 19 July 2025.

This is a nomad tribe that came from Dir, Swat, Hazara, Kohistan and Afghanistan during Katur rule and settled in the southern valleys of Chitral.

- ^ "1998 District Census Report of Chitral". May 1999. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ "Pakistan Census 2017 District-Wise Tables: Lower Chitral District". Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "7th Population and Housing Census - Detailed Results: Table 9" (PDF). www.pbscensus.gov.pk. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ^ "TABLE 1 : AREA, POPULATION BY SEX, SEX RATIO, POPULATION DENSITY, URBAN POPULATION, HOUSEHOLD SIZE AND ANNUAL GROWTH RATE, CENSUS-2023, KPK" (PDF).

- ^ "LITERACY RATE, ENROLMENT AND OUT OF SCHOOL POPULATION BY SEX AND RURAL/URBAN, CENSUS-2023, KPK" (PDF).

Lower Chitral District

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Topography

Lower Chitral District occupies the northwestern part of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in Pakistan, nestled within the Hindu Kush mountain system. It shares borders with Upper Chitral District to the north, Dir District to the south, and Afghanistan's Nuristan and Kunar provinces to the west, while eastern limits adjoin Swat and Dir Upper districts. The district spans approximately from the Lowari Pass southward boundary to northern extents near Barenis and Gobor areas, encompassing the Chitral Valley's southern reaches.[5][6] The terrain consists of rugged, high-relief landscapes dominated by steep mountain slopes and narrow river valleys. Elevations vary significantly, with valley floors around Chitral town at about 1,500 meters above sea level and surrounding peaks exceeding 5,000 meters, contributing to an average district elevation of roughly 3,685 meters. The Chitral River traverses the central valley, shaping alluvial plains suitable for limited agriculture amid otherwise rocky and glacial uplands. Tributaries like the Bumburet River in side valleys further define the topography, fostering isolated settlements in intermontane basins.[7][8][9]Climate and Natural Resources

Lower Chitral District features a moderate continental climate, milder than the colder upper regions due to lower elevations ranging from about 1,000 to 2,500 meters in its valleys, resulting in cold, snowy winters and warm, dry summers. January minimum temperatures average -9°C with occasional snowfall, while July maxima reach 30-35°C in lowland areas, influenced by the region's position in the rain shadow of the Hindu Kush, which limits moisture influx.[10] [11] Annual precipitation totals 300-600 mm, concentrated in spring (peaking at 102 mm in April) and the summer monsoon (July-September), though the driest month, July, sees only 6 mm; this pattern supports limited rainfed agriculture but necessitates irrigation for sustained crop yields. Recent trends show rising temperatures and glacial melt, exacerbating water variability and flash flood risks in high-altitude tributaries.[5] [12] Natural resources are dominated by water from the Chitral River and glacial-fed streams like the Bomboret, providing irrigation for valley agriculture (e.g., wheat, maize, fruits) and untapped hydropower potential amid glacier recession reducing long-term flows by up to 30% since the 1990s. Forests, covering roughly 4.7% of the district, include oak and coniferous species in northern slopes, supporting biodiversity, timber, and regeneration efforts despite deforestation pressures. Mineral deposits, including copper (up to 8.9% in some ores), lead, antimony, and mica, occur in metamorphic terrains, with historical small-scale mining but limited modern extraction due to infrastructure challenges.[11] [13] [14]History

Ancient and Medieval Periods

The Chitral Valley, encompassing Lower Chitral, preserves archaeological evidence of early settlements linked to the Gandharan Grave Culture, dating roughly from 1200 BCE to the early 1st millennium CE. Surveys have identified over a dozen such grave sites in the region, featuring pit and chamber tombs with pottery, iron tools, and personal ornaments indicative of pastoralist communities with ties to broader Indo-Iranian cultural spheres and early trade networks.[15] Recent excavations at sites like Thamuniak Broze, south of Chitral town, have unearthed Iron Age burials with skeletal remains and artifacts, confirming continuous habitation from the late Bronze Age through the proto-historic period.[16] Buddhist influence reached the area by the 3rd century CE, likely via routes from Gandhara, though less extensively than in neighboring Swat. Artifacts such as a unique terracotta figurine from Singoor, depicting a female deity possibly identified as Hariti—a protective yakshini in Buddhist lore—suggest localized veneration within a syncretic religious landscape blending indigenous animism and imported iconography during the Kushan or immediate post-Kushan phases (circa 1st–5th centuries CE).[17] A mid-8th-century burial at Gankoriniotek, potentially linked to Tang Chinese administration or migration, hints at transient East Asian contacts amid the region's role as a Silk Road fringe corridor, though such evidence remains isolated.[18] In the early medieval period (circa 7th–12th centuries), Lower Chitral fell under the sway of Rai or Rais rulers, local dynasties exploiting mineral resources like orpiment and iron, which facilitated economic ties with Central Asian polities.[19] Polytheistic "Kafir" societies, ancestral to the Kalash, dominated the southern valleys, maintaining animist traditions centered on nature deities and wooden idol worship, as preserved in oral histories and archaeological traces of ritual sites.[20] Kho (Khowar-speaking) tribes, originating from upper valleys, expanded southward around 1200–1300 CE, defeating Kalash chieftains and initiating Islamization; by the 14th century, most Kalash in Lower Chitral had converted, though pockets in valleys like Bumburet retained pagan practices into the 16th century under residual chiefdoms.[20] This transition marked the onset of Sunni Islam's dominance, blending with Dardic ethnic substrates amid intermittent raids from Afghan and Mughal peripheries.Princely State Era

The Katur dynasty established control over Chitral in the late 16th century, seizing power from the preceding Raees dynasty around 1570 through the efforts of Sangan Ali and his sons, with Muhtaram Shah I consolidating the rule as the first Mehtar by the early 18th century.[21][22] This marked the beginning of a hereditary monarchy characterized by internal conflicts and expansionist campaigns, maintaining relative independence amid regional powers like the Mughals, Afghans, and later Sikhs.[21] Under Mehtar Aman ul-Mulk (r. 1857–1892), the state reached its territorial peak through conquests in neighboring areas and a subsidiary alliance with the Maharaja of Kashmir in 1877, which aligned Chitral with British interests in the region while preserving internal autonomy.[21][23] A succession crisis following Aman ul-Mulk's death in 1892 led to fratricidal strife, with brief reigns by Afzal ul-Mulk, Nizam ul-Mulk (murdered), and Amir ul-Mulk, culminating in the brief usurpation by Sher Afzal and the famous Siege of Chitral in 1895.[21] British political agent Sir George Scott Robertson and a garrison endured a 48-day siege in Chitral Fort by tribal forces, relieved by expeditions from Gilgit and Peshawar, after which the British installed Shuja ul-Mulk (r. 1895–1936) as Mehtar, formalizing Chitral as a princely state under British suzerainty via subsidiary alliance while the Mehtar retained administrative control over internal affairs.[22][21] Shuja ul-Mulk's long reign stabilized the state, suppressed internal revolts, and supported British efforts during the Third Anglo-Afghan War in 1919, earning Chitral recognition as a 9-gun salute state in 1911.[21][23] Subsequent rulers included Nasir ul-Mulk (r. 1936–1943) and Muzaffar ul-Mulk (r. 1943–1949), under whose tenure Chitral navigated the partition of British India.[21] On 7 November 1947, Muzaffar ul-Mulk signed the Instrument of Accession, integrating Chitral into the Dominion of Pakistan and ending its status as an independent princely state, though the Mehtar retained advisory influence until the full merger as a district in 1969.[23][21] This accession secured Chitral's alignment with Pakistan amid regional instability, including efforts to stabilize Gilgit-Baltistan.[21]Integration into Pakistan and Modern Developments

Following the partition of India in August 1947, the princely state of Chitral, under Mehtar Muzaffar ul-Mulk, acceded to the Dominion of Pakistan by signing the Instrument of Accession on November 6, 1947.[24] The accession was formally accepted by Muhammad Ali Jinnah on February 18, 1948, integrating Chitral into Pakistan while initially preserving its internal autonomy under the mehtar's rule.[24] This decision aligned with the mehtar's earlier expressions of support for the Pakistan Movement, including correspondence with Jinnah in August and October 1947 affirming loyalty to the new state.[25] Chitral's forces, including the Chitral Scouts, contributed to Pakistan's early defense efforts during the 1947–1948 Indo-Pakistani War, particularly in securing northern frontier regions amid tribal uprisings and conflicts over Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan.[26] Post-accession, the state retained semi-autonomous status, with the mehtar continuing as a titular ruler until administrative reforms eroded this arrangement; the monarchy was effectively abolished in 1969 under President Yahya Khan, followed by full integration into Pakistan's provincial structure by Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1971 to diminish the mehtar's influence.[21] By 1972, Chitral transitioned into a formal administrative district of the North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), marking the end of princely privileges and the imposition of centralized governance.[22] In the decades following integration, Chitral's development was hampered by geographic isolation, with limited road access via the snow-prone Lowari Pass restricting trade and mobility until infrastructure upgrades in the late 20th century.[22] Modern initiatives have focused on enhancing connectivity and economic potential, including the construction of the Lowari Tunnel (completed in phases by 2019) to improve year-round access to Peshawar and facilitate trade with Afghanistan.[27] Regional strategies under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) envision Chitral as a transit hub linking Pakistan to Central Asia via the Wakhan Corridor, promoting investments in hydropower, mining, and tourism despite persistent challenges like inadequate rural roads and energy shortages.[28] The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government has advanced projects such as the Chitral Economic Zone to boost local industries, though uneven implementation has widened urban-rural disparities.[27][29]Creation of the District

The former Chitral District, established as an administrative unit of Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) in 1969, was bifurcated into two separate districts by the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government on November 20, 2018.[30] This division separated the northern, more remote portions—headquartered at Booni—into the newly formed Upper Chitral District, while the southern areas, including the district headquarters at Chitral town, were redesignated as Lower Chitral District.[30] The bifurcation was enacted under Sections 5 and 6 of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Land Revenue Act, 1967, aiming to improve administrative efficiency and service delivery in the region's challenging terrain.[31] Lower Chitral encompasses approximately the area from the Lowari Pass southward to the border with Dir District, covering key valleys such as Ayun, Kalash, and Drosh, with a focus on enhancing local governance for its population of around 200,000 at the time.[5] This restructuring followed years of advocacy from local stakeholders for decentralized administration, reflecting the geographical divide imposed by the Chitral River and high passes that historically isolated northern areas during winter closures.[30] The move aligned with broader provincial efforts to create smaller districts for better resource allocation, though it initially faced logistical challenges in establishing separate infrastructure and staffing.[31]Administrative Divisions

Tehsils and Union Councils

Lower Chitral District is subdivided into two tehsils: Chitral Tehsil and Drosh Tehsil.[32] These divisions stem from the 2018 bifurcation of the former Chitral District, with Lower Chitral encompassing the southern portions previously administered under Chitral Tehsil, which included the sub-divisions of Drosh and Lutkho; Drosh was formalized as a separate tehsil to enhance local governance.[33] Chitral Tehsil, the administrative headquarters of the district, spans 6,127 square kilometers and recorded a population of 211,374 in the 2023 census, yielding a density of 34.5 persons per square kilometer. Drosh Tehsil, located downstream along the Chitral River, covers 331 square kilometers with 109,033 residents as of 2023, resulting in a higher density of 329.4 persons per square kilometer due to its more accessible terrain and agricultural potential.[34] Union councils serve as the primary grassroots administrative units within these tehsils, handling local matters such as development projects, dispute resolution, and basic services under Pakistan's local government framework. Lower Chitral District encompasses 14 union councils, distributed across the two tehsils, which were restructured from the former Chitral District's 24 union councils following the bifurcation.[35] These councils facilitate community-level representation and were last delineated during the 2015-2021 local government term, with elections influencing resource allocation for infrastructure like roads and irrigation in remote valleys.[36]Governance Structure

The governance of Lower Chitral District operates under the administrative framework of the Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, with the Deputy Commissioner serving as the principal executive authority and coordinating head of district-level operations. Appointed as a civil servant from provincial services such as the Pakistan Administrative Service or Provincial Management Service, the Deputy Commissioner oversees the implementation of provincial policies, revenue administration, and inter-departmental coordination across sectors including health, education, agriculture, and public works.[37][2] Key responsibilities of the Deputy Commissioner include acting as District Collector for land revenue matters, exercising magisterial powers to uphold law and order in collaboration with the District Police Officer, managing the district treasury, and directing disaster response and public safety initiatives. The office also handles regulatory approvals such as domicile certificates, arms licenses, and no-objection certificates, while monitoring development projects and ensuring compliance with environmental and building regulations.[38][39] Assisting the Deputy Commissioner are Additional Deputy Commissioners and specialized sections within the district secretariat, which facilitate day-to-day executive functions and public grievance redressal. Line departments, headed by officers from provincial cadres, report developmental progress to the Deputy Commissioner, who consolidates reports for provincial oversight. Although the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Local Government Act, 2013, establishes elected bodies at the tehsil and village council levels for localized service delivery and planning, the district administration retains core executive control, particularly in revenue, security, and coordination roles, reflecting a hybrid bureaucratic-elected model.[40][41]Demographics

Population and Growth Trends

According to the 2023 Pakistan census conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, Lower Chitral District has a population of 320,407, comprising 163,584 males and 156,823 females, with a sex ratio of 104.31 males per 100 females.[1] The district spans 6,458 square kilometers, yielding a population density of 49.61 persons per square kilometer, reflecting its predominantly rural and mountainous character, where 82% of the population resides in rural areas.[1] There are 46,028 households in the district.[42] Prior to the district's creation in 2018 from the former Chitral Tehsil, the area's population was recorded at 278,122 in the 2017 census and 184,874 in the 1998 census.[43] This indicates an average annual growth rate of approximately 2.1% from 1998 to 2017, lower than the national average of around 2.4% during that period, attributable to factors such as geographic isolation, limited economic opportunities, and high emigration for education and employment.[44] From 2017 to 2023, the annual growth rate accelerated to 2.4%, aligning more closely with provincial trends in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, potentially driven by improved infrastructure like the Lowari Tunnel and returning migrants.[44] Overall, population growth remains moderate compared to urbanizing districts in Pakistan, constrained by the region's rugged terrain and pastoral economy.Ethnic Composition and Languages

The predominant ethnic group in Lower Chitral District consists of the Kho people, who form the core of the Chitrali population and maintain a distinct identity separate from neighboring Pashtuns, Gilgitis, and Tajiks.[45] This group primarily inhabits the central and northern areas of the district, with their demographic dominance reflected in the widespread use of Khowar, a Dardic language of the Indo-Aryan branch, as the primary tongue and lingua franca.[5] Khowar speakers number approximately 400,000 across the broader Chitral region, encompassing Lower Chitral, where it functions as the medium for local administration, education at lower levels, and daily communication.[46][47] Pashtun communities, speaking Pashto—an Eastern Iranian language—reside mainly in the southeastern periphery of the district, near the Afghan border, representing a notable minority influenced by cross-border ties and pastoral migrations.[48] Their presence stems from historical settlements and trade routes, though they remain outnumbered by Khowar speakers in the district's overall composition. The Kalash form a small but culturally distinct indigenous ethnic enclave, confined to the three valleys of Birir, Bumburet, and Rumbur in the southwestern part of Lower Chitral, with a population estimated at around 3,000 individuals as of recent assessments.[49] This group speaks Kalasha, another Dardic language unintelligible with Khowar, preserving unique oral traditions amid pressures from linguistic assimilation to the dominant Khowar.[48] The Kalash comprise roughly 1% of the former Chitral District's population, a proportion that has remained stable despite external narratives of decline, underscoring their resilience as a relict population with Indo-Aryan roots diverging from surrounding groups.[50] Minor linguistic pockets include Gojri among nomadic herders and remnants of Nuristani languages like Gawarbati in isolated border hamlets, but these do not significantly alter the district's overarching Dardic linguistic profile, which aligns with Chitral's classification across Indo-Aryan, Iranian, and Nuristani families.[48] Demographic data from the 2017 Pakistan census, while not disaggregating ethnicity finely, supports Khowar as the majority mother tongue, with Pashto and Kalasha as secondary, based on reported speaker distributions in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's northern districts.[51]Religious Affiliations

The population of Lower Chitral District is predominantly Muslim, with Sunni Islam of the Hanafi school comprising the vast majority, reflecting the ethnic Kho people's primary religious adherence. Ismaili Shia Muslims, more concentrated in Upper Chitral, maintain a limited presence in Lower Chitral's peripheral areas.[52][53] A notable religious minority consists of the Kalash people, who practice an indigenous polytheistic faith centered on animistic and nature-worship elements, distinct from surrounding Islamic traditions; this group numbers approximately 3,000 to 4,000 adherents residing in the Bumburet, Rumbur, and Birir valleys.[50][54] Other religious communities, such as Christians or Hindus, are negligible, with no significant reported populations or institutions.[55]Economy

Primary Sectors: Agriculture and Pastoralism

Agriculture in Lower Chitral District is primarily subsistence-based, adapted to the district's high-altitude, rugged terrain where cultivable land is severely limited by steep slopes and a short frost-free growing period of 120-150 days. Farmers employ terraced fields irrigated via traditional kuhls—communally maintained gravity channels fed by the Chitral River, its tributaries, and glacial meltwater—to grow staple cereals including wheat, maize, barley, and minor amounts of rice and sorghum.[56][57] These crops form the backbone of food security, with wheat as the dominant rabi (winter) crop and maize as the key kharif (summer) staple, though yields remain low due to reliance on rain-fed supplements in unirrigated areas and vulnerability to erratic precipitation.[58] Fruit cultivation thrives in suitable microclimates, particularly apricots, walnuts, apples, mulberries, grapes, pears, cherries, and almonds, which are harvested seasonally and support limited cash income through local markets or drying for preservation and trade.[57] Vegetables such as potatoes, peas, beans, onions, tomatoes, and chilies supplement diets and are promoted through varietal trials at the Agricultural Research Station in Seenlasht, which focuses on high-yielding, climate-resilient strains to enhance productivity amid soil nutrient deficiencies and water scarcity.[58][57] Overall, crop farming engages a majority of the rural population but contributes modestly to the district economy, constrained by small landholdings averaging under 1 hectare per household and minimal mechanization.[59] Pastoralism integrates with agriculture as a key livelihood strategy, involving the herding of goats, sheep, and cattle—prioritized for milk, meat, wool, hides, and draft power—in a transhumant system that exploits seasonal vertical migrations to high-elevation pastures above 3,000 meters during summer.[60][57] In lower valleys, daily herding to nearby slopes supplements this, though trends show declining herd sizes per household, reduced emphasis on large ruminants like cattle, and partial shifts to sedentarization driven by population growth, fodder shortages, and flood-damaged grazing lands in areas like Rumbur and Birir.[61][62] Livestock populations in the broader Chitral area, reflective of Lower Chitral patterns, totaled around 174,842 cattle heads in 2006, with goats and sheep dominating due to their adaptability to sparse rangelands covering much of the district's non-arable expanse. This sector provides essential protein and income diversification but faces pressures from overgrazing, climate variability, and competition with expanding settlements.Tourism and Emerging Industries

![The City of Chitral and Tirich Mir.jpg][float-right] Tourism in Lower Chitral District centers on its rugged Hindu Kush landscapes, cultural heritage of the Kalash people, and historical sites. Key attractions include the Kalash valleys of Bumburet, Rumbur, and Birir, home to the indigenous Kalash community known for their polytheistic traditions and festivals, drawing cultural tourists.[63] Chitral Gol National Park offers wildlife viewing and trekking opportunities, while Garam Chashma's natural hot springs provide therapeutic bathing.[63] Chitral Fort, a 17th-century structure overlooking the Chitral River, and Ayun Valley's scenic confluence of rivers attract adventure seekers and photographers.[64] The district's tourism potential emphasizes ecotourism, with studies highlighting sustainable development to minimize environmental impacts while boosting local income and employment.[65] Eco-tourism initiatives have positively affected local communities by increasing economic opportunities, though infrastructure limitations hinder broader access.[66] Annual events like Kalash festivals and polo matches further promote cultural immersion, contributing to seasonal visitor influxes primarily from domestic and regional sources.[67] Emerging industries focus on resource processing and value-added activities to diversify beyond subsistence agriculture. The Chitral Economic Zone prioritizes mineral processing, handicrafts, and food packaging, including dry fruit and marble sectors, to stimulate investment and job creation.[68] Mining beneficiation for copper and antimony deposits in areas like Krinj-Shughor shows promise for strategic business models in a low-carbon future. Hydropower development, gemstone mining, and high-value crops like saffron cultivation represent growth areas, with saffron trials aimed at economic upliftment through export potential.[13][70] These sectors leverage the district's natural resources, though realization depends on infrastructure improvements and private investment.[71]Challenges and Development Initiatives

Lower Chitral District faces significant challenges from recurrent natural disasters, exacerbated by its remote, mountainous terrain and vulnerability to climate change. Flash floods in 2023 devastated homes and livelihoods in areas like Drosh, displacing families and destroying agricultural assets, while earlier events such as the 2010 floods damaged infrastructure across the district. Rapid glacier melting in adjacent regions like Broghil and Tirich, reported in September 2025, threatens water security and increases risks of glacial lake outburst floods, contributing to soil erosion and reduced arable land. A 2025 study in Lotkuh Valley highlighted how climate variability disrupts pastoral and farming livelihoods, leading to crop failures and livestock losses due to erratic precipitation and temperature shifts. Infrastructure deficits persist, including inadequate roads and bridges prone to washouts, limiting access to markets and services; a 2018 assessment noted chronic underinvestment in the broader Chitral area, hindering economic integration. Poverty remains acute, with limited diversification beyond subsistence agriculture and pastoralism, compounded by poor transport that affects sapling survival for afforestation efforts. Development initiatives focus on resilience-building and sector-specific interventions. The Chitral Climate Change Adaptation Action Plan, finalized in March 2025, outlines strategies for flood mitigation, including early warning systems and community-based disaster risk reduction in Lower Chitral. In education, the National Commission for Human Development (NCHD) signed a memorandum of understanding with the University of Chitral in October 2025 to expand literacy programs and outreach in the district, while UN-Habitat handed over disaster-resilient school upgrades in September 2025 across Lower Chitral to enhance structural safety against earthquakes and floods. Health efforts include a community-integrated mental health initiative launched in October 2025, aiming to raise awareness and provide grassroots support services. The Sarhad Rural Support Programme (SRSP) maintains extensive coverage in Lower Chitral's 14 union councils, implementing projects in water management, energy, and livelihoods since the early 2000s. Energy development emphasizes hydropower, with micro- and mini-hydropower schemes initiated by SRSP providing electricity to remote villages, drawing from lessons in sustainable community management. Larger projects, such as the proposed Mujigram-Shoghore scheme on the Lutkho River and the 99 MW Arkari Gol run-of-river project, target expanded capacity while assessing environmental impacts. Tourism promotion accelerated through the Chitral Economic Development Conference in October 2025, which identified investment opportunities, alongside government efforts to develop 42 sites and conduct feasibility studies for tourism corridors by 2025. The Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund (PPAF)'s Chitral Growth Strategy invests in infrastructure, health, and education to foster inclusive growth, though implementation faces logistical hurdles in high-altitude areas. Wildlife conservation generates revenue, with the department auctioning trophy hunting permits for $1.9 million in the 2025-26 season, funding habitat protection.Culture and Society

Traditional Practices and Festivals

The Kalash people, indigenous to the valleys of Bumburet, Rumbur, and Birir in Lower Chitral District, maintain distinct traditional practices rooted in their animistic-polytheistic beliefs, including ritual sacrifices to deities, communal feasting with mulberry wine and cheese, and gender-specific dances where women in embroidered black attire perform energetic steps accompanied by flute and drum music.[72][73] These practices emphasize harmony with nature and seasonal cycles, contrasting with the Sunni Islamic customs of the majority Khowar-speaking population, who integrate Persian-influenced hospitality rituals like atthi (guest-sharing meals) and folk dances such as shishtari during weddings.[74] Key festivals among the Kalash include the Chilam Joshi spring celebration, held from approximately May 13 to 16, marking the end of winter and dairy season with processions to sacred sites, goat sacrifices, and all-night dances invoking fertility gods like Dizane.[75][76] The Uchal harvest festival in late August, around the 20th, features thanksgiving rituals for milk and grain yields, including decorated cattle processions, archery contests, and feasting to honor mountain spirits.[75] The winter Chaumos (or Choimus) festival in December spans several days of purification rites, bonfires, and choral prayers, culminating in animal offerings and masked dances to ward off evil during the solstice period.[73][77] In the broader Muslim communities of Lower Chitral, traditions revolve around Islamic observances like Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, augmented by local customs such as polo matches and folk singing during weddings, while the district-wide Jashn-e-Chitral in mid-September showcases archery, wrestling, and traditional music performances drawing from both Kalash and Khowar elements.[78][74] These events preserve oral epics and instrumental traditions using the sitar and rabab, though modernization and religious pressures have led to declining participation in some ritualistic aspects among younger generations.[72]Linguistic and Artistic Heritage

The primary language of Lower Chitral District is Khowar, an Indo-Aryan Dardic language spoken by the majority Kho population across the region, serving as the lingua franca for communication and cultural expression.[79] Khowar features a rich oral literary tradition, including epic poetry and folk tales that preserve historical narratives and moral teachings, with influences from ancient Iranian and Central Asian linguistic substrates evident in its phonology and vocabulary.[80] In the Kalash valleys of Bumburet, Rumbur, and Birir within Lower Chitral, the Kalasha language—an endangered Dardic tongue with approximately 3,000 to 5,000 speakers—predominates among the indigenous Kalash people, distinguished by its unique phonological traits such as voiced aspirates differing from related languages like Khowar.[81] Kalasha maintains a vital oral heritage through myths, songs, and ritual chants that encode cosmological beliefs and seasonal cycles, though it faces pressure from Khowar dominance and limited formal documentation.[79] Other minority languages, including Phalura and Gawar-Bati (both Indo-Aryan) and traces of Nuristani dialects, persist in isolated pockets, reflecting the district's linguistic diversity shaped by historical migrations from the Hindu Kush.[48] Artistically, Lower Chitral's heritage centers on Kalash wood carvings, which adorn traditional multi-story homes with intricate motifs of humans, animals, and mythical figures, blending functional architecture with symbolic representation of nature and ancestry—a craft sustained by familial apprenticeships and using local walnut and deodar woods.[82] These carvings, often featuring exaggerated forms and narrative scenes, trace to pre-Islamic influences and contrast with the plainer Islamic motifs in Kho areas. Embroidery and textiles form another pillar, with Kalash women producing vibrant garments from black wool robes accented by cowrie shells, multicolored threads depicting floral and geometric patterns, symbolizing fertility and protection.[83] Music and dance constitute dynamic expressions, particularly among the Kalash, where communal performances accompany festivals using instruments like the rubab (a lute) and dairo (drum) to enact rhythmic circle dances that mimic natural rhythms and communal harmony, preserving oral histories through improvised verses in Kalasha.[84] In broader Chitral contexts, Khowar folk music echoes these with shepherd songs and epic recitations, though artistic output remains largely non-commercial and tied to agrarian lifestyles rather than institutional patronage.[80]Social Structure and Family Systems

The social structure of Lower Chitral District is organized around tribal clans and kinship networks, reflecting a patrilineal and hierarchical system influenced by historical feudal arrangements and local ethnic groups such as the Kho and Pashtuns. Prominent clans, including the Razakhel—descendants of Muhammad Raza and considered one of Chitral's largest—maintain welfare organizations and social cohesion through collective decision-making, often guided by elders in informal councils reminiscent of jirgas.[85] This clan-based organization facilitates resource sharing and dispute resolution in a rugged, agrarian environment, though modernization and administrative changes post-1970s have diluted feudal hierarchies without eliminating tribal identities.[86] Family systems predominantly follow a patriarchal joint or extended model, where multiple generations—typically grandparents, parents, children, and grandchildren, numbering over 10 members—reside together under the authority of the senior male, who manages household affairs, land, and decisions.[87] Upon his death, authority passes to the eldest son, reinforcing patrilineal inheritance that favors male heirs in property distribution.[88] Women occupy secondary roles, primarily in domestic spheres, with limited public autonomy due to cultural norms emphasizing male guardianship.[89] A distinctive feature is the low consanguinity rate of approximately 12%, the lowest among Pakistani populations, attributed to extended family dynamics treating cousins as siblings, sparse land-owning elites reducing marriage-for-property incentives, and exogamous preferences that expand social alliances across clans or villages.[45] Marriages emphasize compatibility within caste or neighboring groups but avoid close kin, often arranged through community events like weddings or funerals to navigate geographical isolation.[45] Shifts toward nuclear families have emerged in urbanizing areas of Lower Chitral, driven by education, migration for work, and economic pressures, yet joint systems persist in rural settings for mutual support amid limited infrastructure.[87] This resilience underscores causal factors like resource scarcity and security needs in a border region, where extended kin networks provide buffers against external threats and economic volatility.[45]Government and Politics

Electoral Representation

Lower Chitral District forms part of the NA-1 (Chitral Upper-cum-Lower Chitral) constituency in the National Assembly of Pakistan, which encompasses the entirety of both Upper and Lower Chitral districts as delimited by the Election Commission of Pakistan following the 2023 census-based redistricting.[90] In the February 8, 2024, general elections, Abdul Latif, running as an independent candidate with backing from Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI), secured victory in NA-1 with 61,834 votes, defeating Muhammad Talha Mehmood of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (F) who received 42,897 votes.[91] [92] Voter turnout in the constituency was approximately 45%, reflecting challenges such as remote terrain and winter conditions that delayed polling in some upper areas until February 10.[92] For the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Provincial Assembly, Lower Chitral District constitutes the PK-2 (Chitral Lower) constituency, covering tehsils including Chitral, Ayun, and Kalash valleys.[93] Fateh Ul Mulk Ali Nasir, a member of the former royal family of Chitral and running as an independent with PTI support, won the seat in the 2024 elections, marking his first term in the assembly after securing a plurality amid competition from candidates like Saleem Khan of Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP).[94] [95] This outcome aligned with PTI-affiliated independents dominating Chitral's seats, consistent with the party's strong local appeal rooted in anti-establishment sentiments and development promises.[95] Local electoral representation occurs through the district's union councils under Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's Local Government Act 2013, with Lower Chitral divided into approximately 20-25 union councils electing councilors and nazims via direct vote; however, recent elections in 2019-2021 saw low turnout due to security concerns and logistical issues in mountainous areas.[2] Political dynamics in these elections often favor tribal and familial networks, with PTI and JUI-F holding sway among the predominantly Sunni Kho and Kalash communities, though independent candidates frequently prevail by leveraging personal influence over party machinery.[95]Local Administration and Policies

The local administration of Lower Chitral District is headed by a Deputy Commissioner, who is responsible for executive functions, including maintaining law and order, ensuring security, regulating public activities, and delivering services such as domicile certificates, arms licenses, and no-objection certificates.[2] The current Deputy Commissioner is Rao Muhammad Hashim Azeem of the Pakistan Administrative Service, assisted by an Additional Deputy Commissioner for general administration, Abdul Salam.[2] The district is divided into two tehsils—Chitral and Drosh—each managed by an Assistant Commissioner, with further subdivision into union councils that form the base of local governance structures.[5] Governance in the district follows the framework of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Local Government Act, 2013, which establishes tehsil councils, village councils, and neighbourhood councils to handle local affairs, though the district tier was abolished via amendments in 2019, shifting more authority to provincial and tehsil levels.[96] Policies emphasize decentralized service delivery, with the Deputy Commissioner's office facilitating digital platforms for transparency in administrative processes and resource allocation.[2] Development-oriented policies include community-driven initiatives under the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Community Driven Local Development framework, aimed at enhancing local responsiveness, employment, and infrastructure through participatory planning across union councils.[97] Specific sectoral policies address the district's unique cultural and geographic features, notably through the Special Purpose Kalash Valleys Development Authority, established under rules notified in 2020, which promotes sustainable tourism, heritage preservation, and cultural development in the Kalash valleys of Lower Chitral while extending to notified adjacent areas.[98] Urban policies are guided by the Chitral City Master Plan for 2024–2042, prepared by the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Urban Policy and Planning Unit, focusing on planned expansion, infrastructure resilience, and economic integration in the district capital.[99] These efforts are supported by provincial finance and planning mechanisms, which allocate funds for annual development programs and budgeting in areas like agriculture and rural support.[100]Infrastructure and Development

Transportation Networks

The primary road access to Lower Chitral District connects via the 8.5 km Lowari Tunnel, completed in 2018 and operational since 2019, linking Chitral town to Dir Lower District and enabling year-round vehicular travel to Peshawar, approximately 300 km south, reducing previous seasonal closures at Lowari Pass due to snowfall.[101][102] Prior to the tunnel, the 3,118 m Lowari Pass route, prone to avalanches and blockages for up to four months annually, served as the sole southern link, with clearance for light traffic only after snowmelt.[103] Internal road networks, including the Shandur Road northward to Upper Chitral, remain underdeveloped with frequent damage from floods and landslides, as evidenced by disruptions from heavy rains on September 17, 2025, affecting multiple bridges and segments.[104][105] Air transportation is facilitated by Chitral Airport (IATA: CJL), located 3.7 km north of Chitral town, offering domestic flights primarily operated by Pakistan International Airlines to Islamabad and Peshawar, with schedules varying seasonally due to weather constraints in the Hindu Kush region.[72] The airport's single runway supports small aircraft, serving as a critical link for remote areas but limited by frequent closures during winter fog and snow.[106] Local connectivity relies on a sparse network of district roads and bridges, including the 100 m Singur Bridge installed in a remote area to enhance economic access, and recent constructions like the Patai and Ursoon Bridges in Ashiret Union Council funded by development initiatives.[107][108] No railway infrastructure exists, and public transport consists mainly of buses and jeeps along unmetaled tracks vulnerable to natural hazards, contributing to logistical challenges for goods and passengers.[104][6]Education and Healthcare Facilities

The education system in Lower Chitral District encompasses government-managed primary, middle, high, and higher secondary schools overseen by the District Education Office, with ongoing infrastructure upgrades in remote border areas to enhance access for marginalized communities.[109][35] Recent initiatives include the inauguration of six renovated government schools in December 2024 by the Sarhad Rural Support Programme (SRSP), funded by the German government, targeting structural improvements in underserved locations.[110] Higher education options are limited but include sub-campuses of institutions such as the University of Chitral and Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, serving student enrollments amid geographic isolation.[111] The district's literacy rate for individuals aged 10 and above was recorded at 66.1% in the 2023 census, reflecting male literacy of 76.8% and female literacy of 54.8%, higher than many Khyber Pakhtunkhwa districts but constrained by rural disparities and seasonal inaccessibility.[44] Healthcare infrastructure centers on the District Headquarters (DHQ) Hospital in Chitral town, categorized as a medium-level facility providing secondary care, alongside tehsil headquarters hospitals and approximately 65 Basic Health Units (BHUs) and Rural Health Centers (RHCs) for primary services.[112][113] As of September 2025, acute doctor shortages— with only 20 medical officers available district-wide—have disrupted primary care delivery, leading to operational disarray in remote units and forcing reliance on understaffed facilities amid high patient volumes averaging over 22,000 daily visits across sites in prior assessments.[113][114] Supplementary efforts include NGO interventions, such as the Aga Khan Health Service's 20-bed emergency center in Garamchashma established in June 2020 for infectious disease response, and mHealth applications tested across 63 facilities in 2025 to bolster immunization and service tracking in Upper and Lower Chitral.[115][116] Staff challenges, including heavy workloads and fatigue in valleys like Karimabad, exacerbate gaps in rural nursing and overall capacity.[117]Security Issues

Militancy and Cross-Border Threats

Lower Chitral District, sharing a porous border with Afghanistan's Kunar and Nuristan provinces, has experienced sporadic militancy primarily driven by cross-border incursions from Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) militants based in Afghan territory. These threats intensified following the 2021 Taliban takeover in Afghanistan, which provided safe havens for TTP factions seeking to expand operations into Pakistan's northwestern regions. Pakistani security assessments attribute the uptick to TTP's strategic use of the rugged Durand Line terrain for infiltration, aiming to establish footholds in relatively stable areas like Chitral to bolster recruitment and logistics.[118][119] A notable escalation occurred in 2011 when approximately 200-300 militants from Afghanistan launched coordinated attacks on seven Frontier Corps (FC) checkposts in Chitral, resulting in the deaths of 25 Pakistani soldiers and the temporary seizure of positions before security forces regained control. More recently, on September 6-7, 2023, TTP fighters numbering in the scores to hundreds attempted a large-scale raid across the border into Chitral's border areas, targeting multiple army and FC posts in an effort to capture territory and demonstrate resurgence. Pakistani forces repelled the assault, killing at least 12 TTP militants and reporting four soldiers killed, with the TTP claiming responsibility via its media wing; Afghan authorities later acknowledged arresting over 200 suspected militants involved, though they denied state complicity.[120][121][118] In 2025, cross-border threats persisted amid heightened Pakistan-Afghanistan tensions, including Pakistani airstrikes on TTP targets inside Afghanistan starting October 9. On the night of October 11-12, Afghan Taliban forces and affiliated TTP elements attacked Pakistani posts in Chitral, alongside other border regions like Kurram and Bajaur, in what Pakistan described as a coordinated offensive involving hundreds of fighters. Casualty figures remain disputed: Pakistan's Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) reported killing over 200 militants while losing 23 troops, whereas Afghan Taliban spokesmen claimed to have killed 58 Pakistani soldiers and captured 25 posts in retaliation for the airstrikes. Further clashes on October 26 resulted in five Pakistani soldiers and 25 militants killed, underscoring ongoing vulnerabilities in Lower Chitral's frontier zones despite fencing efforts and local levies like the Chitral Scouts.[122][123][124][125]Sectarian Conflicts

Lower Chitral District, predominantly Sunni Muslim in composition, has experienced sporadic sectarian tensions primarily with the neighboring Ismaili Shia communities concentrated in Upper Chitral, exacerbated by cross-border influences and political maneuvering. While inter-sect marriages and cooperative social practices remain relatively common—higher than in many other Pakistani regions—the district's Sunni majority has occasionally clashed with Ismaili institutions and individuals over perceived religious and economic encroachments. These conflicts, though less frequent and severe than in areas like Kurram or Gilgit-Baltistan, underscore vulnerabilities to external militant ideologies and local resource disputes.[53][52] A notable early incident occurred in 1982, when sectarian violence erupted across Chitral, resulting in approximately 60 Ismailis killed and the burning of community buildings, amid broader anti-Ismaili sentiments fueled by land ownership disputes and ideological agitation. In southern Chitral—now part of Lower Chitral—a 1995 killing of a Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI) leader by an Ismaili individual, stemming from a family feud, risked escalation but was contained through intervention by JUI leadership, highlighting the role of informal religious networks in averting wider conflict. Further violence targeted Ismaili-linked development efforts in 2004, when two employees of the Aga Khan Foundation were murdered in Chitral by alleged Sunni extremists, reflecting opposition to the organization's perceived promotion of Ismaili interests.[126][53][127] Political dynamics have intensified divisions, with Sunni-majority Lower Chitral voters increasingly favoring sect-aligned candidates in elections, as seen in the 2018 polls where alliances like the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal labeled Ismailis as non-Muslims to consolidate support. Threats from groups like the Pakistani Taliban in 2014 explicitly targeted Ismailis in Chitral valleys, vowing armed struggle against them alongside the Kalash minority, though these did not materialize into large-scale attacks in Lower Chitral. More recently, on May 23, 2025, local authorities in Chitral city—within Lower Chitral—imposed a ban on Ismaili butchers supplying meat to Sunni markets, citing unspecified religious concerns but widely viewed as discriminatory economic exclusion; the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan condemned it as a threat to pluralism, warning of eroded trust and heightened intolerance.[128][52][129] Despite these episodes, Lower Chitral's sectarian landscape benefits from geographic isolation and cultural intermingling, limiting militancy spillover from Afghanistan, but analysts note rising risks from blasphemy accusations, rejection of Ismaili-backed projects (e.g., educational initiatives), and influxes of conservative Sunni settlers, which could politicize latent grievances into sustained conflict absent robust state mediation.[53][52][130]Social Challenges

Mental Health and Suicide Epidemic

Lower Chitral District faces a pronounced suicide crisis, with rates exceeding national averages despite the region's relative isolation from broader criminality. In the five years preceding September 2025, the district recorded 63 suicides, disproportionately affecting women amid underlying mental health strains and social pressures.[131] Overall, Chitral District—encompassing Lower Chitral—reported 176 suicides from 2013 to 2019, equating to an annualized rate far above Pakistan's estimated 7.5 per 100,000 population as of 2012 WHO data.[132][133] Recent incidents underscore persistence, including four suicides in July 2025, three involving women, often linked to domestic disputes.[134] Domestic violence emerges as the predominant trigger, particularly for married women, compounded by sub-factors such as spousal abuse, familial discord, economic dependency, and restricted autonomy in patriarchal structures.[135] Mental health challenges, including untreated depression and anxiety, intersect with these, exacerbated by academic competition among youth, forced marriages, and flawed dispute resolution mechanisms that prolong grievances.[136] Youth suicides have surged sociologically, defying Chitral's high literacy rates (over 70% in some areas), with factors like unemployment, cultural stigma against seeking help, and remote geography limiting access to counseling.[137][138] Notably, suicide incidence remains lower in the Kalash valleys of Lower Chitral, attributed to indigenous cultural practices fostering resilience, communal support, and a life-affirming worldview that contrasts with mainstream Pashtun-influenced norms elsewhere in the district.[139][140] Institutional responses lag, with minimal dedicated mental health infrastructure; interventions focus reactively on police investigations rather than preventive counseling or community programs, despite calls for targeted youth mental health initiatives.[141] Stigma and criminalization of suicide under Pakistani law further deter reporting and treatment, perpetuating underdiagnosis of underlying psychiatric conditions.[142]Gender Dynamics and Domestic Issues

In Lower Chitral District, gender dynamics are shaped by a conservative patriarchal framework prevalent among the Muslim majority, where men hold primary authority in household decisions, economic activities, and public life, while women are largely confined to domestic roles with limited mobility and autonomy. This structure perpetuates inequalities in access to education and healthcare, as evidenced by women's restricted decision-making in reproductive health matters, where only about 10% independently choose healthcare options compared to 37% controlled by husbands. Cultural norms emphasize family honor and male dominance, leading to undervaluation of daughters as economic burdens due to dowry expectations and preference for sons as future providers. In contrast, the Kalash communities in the Bumburet, Rumbur, and Birir valleys exhibit more egalitarian practices rooted in their animist traditions, allowing women greater freedoms such as public participation in festivals, alcohol consumption, and vocal expression in community matters, which starkly differ from the purdah-observing norms of neighboring Muslim groups.[143] Domestic violence remains a significant issue, with local estimates indicating a 67% prevalence in Chitral based on electronic media reports, often normalized within joint family systems and exacerbated by factors like drug addiction, gender imbalances, and intergenerational transmission of norms. Victims seldom pursue formal recourse due to stigmatization, fear of escalating abuse, potential loss of child custody, procedural hassles, and prioritization of family reputation, instead relying on informal supports such as parental kin or community jirgas and arbitration boards. Early marriage contributes to these vulnerabilities, particularly among adolescent girls facing curtailed education (with female literacy at 54.77% district-wide in 2023 versus 76.81% for males, reflecting progress from 22.09% in 1998 but persistent gaps), which limits economic independence and heightens risks in sexual and reproductive health, including low modern contraception uptake (10-15% in Chitral).[144][44][145][143] Among the Kalash, women's enhanced agency mitigates some domestic pressures; they retain rights to select partners, dissolve marriages unilaterally, and inherit property, practices that have drawn Muslim suitors and led to interfaith unions where Kalash women sometimes adopt veiling post-conversion, highlighting tensions between cultural preservation and external influences. However, even here, traditional seclusion during menstruation in bashali houses underscores ongoing ritual separations, though these afford temporary relief from labor. Overall, while Ismaili Muslim influences via development networks have boosted female enrollment and literacy to near parity in primary schools in some areas, broader societal resistance confines educated women to homes, underscoring causal links between low schooling, early unions, and entrenched power asymmetries.[146][147][148][145]Recent Developments

Urban Planning and Environmental Adaptation

Chitral City serves as the principal urban hub of Lower Chitral District, with the Master Plan 2024-2042 delineating a study area of 29.75 km² to accommodate projected population growth from 56,450 in 2022 to 84,485 by 2042 at an annual rate of approximately 2%.[99] The plan counters rapid urbanization—evidenced by built-up area expansion from 2.86 km² in 2002 to 3.62 km² in 2022—through strategies favoring compact infill development in existing neighborhood councils and controlled extension into village councils, enforcing 80% horizontal and 20% vertical construction to minimize sprawl into agricultural and steep terrains.[99] Land use zoning allocates 17.33% for residential purposes (1.70 km²), 2.14% for commercial (0.17 km²), and 27.21% for agriculture (8.10 km²), alongside dedicated zones for recreation, health, education, and a satellite town to foster tourism, trade connectivity with Central Asia, and mixed-use walkable neighborhoods.[99] Infrastructure provisions encompass road network enhancements with widened primary arteries, fixed minibuses on designated routes, expanded water supply to 2.18 million gallons per day via additional tube wells and tanks, and sewerage systems culminating in two wastewater treatment plants handling 7.1 million gallons daily by 2042, all calibrated for solid waste generation rising to 25.136 tons per day.[99] Adaptation to environmental hazards integrates resilience against Seismic Zone-4 earthquakes and Chitral River flooding, mandating early warning systems, evacuation protocols, and structures using wood, concrete, and steel; flood defenses include retaining walls, elevated parks, and a 50-meter riparian buffer across 2,790.54 acres to curb erosion.[99] Sustainability features counter observed vegetation decline through 8,332.81 acres of Miyawaki-method urban forestation with native species, 1,402.20 acres of conservation for wetlands and wildlife corridors, and check dams for water harvesting, aligning with broader efforts like the Aga Khan Agency for Habitat's 2024 project enhancing community disaster response in vulnerable locales.[99][149] These measures address escalating risks from glacial recession and temperature increases in the Eastern Hindu Kush, where summer air temperatures and land surface warming have accelerated ice loss.[150]

Disaster Response and Economic Projects

Lower Chitral District experiences frequent natural disasters due to its location in the Hindu Kush mountains, including flash floods from heavy monsoon rains, glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), and landslides, which have intensified with climate change. In September 2024, devastating floods damaged infrastructure, disrupted livelihoods, and affected thousands in Chitral, with Lower Chitral's valleys like Ayun and Bomboret seeing widespread inundation of homes, roads, and agricultural lands. Similar events struck in 2023, with monsoon floods causing extensive harm to housing, education facilities, and transport networks across the district. On September 17, 2025, torrential rains triggered flash floods that destroyed bridges, roads, and farmland in Lower Chitral, isolating communities and halting connectivity. These disasters have been recurrent, with prior incidents in 2022 exacerbating vulnerabilities in remote areas lacking robust early warning systems. Disaster response efforts involve coordination between provincial authorities, the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), and NGOs. The Aga Khan Agency for Habitat (AKAH) initiated community resilience programs in October 2025, emphasizing preparedness through training on early warnings for floods and GLOFs, alongside infrastructure hardening like embankments. Muslim Aid provided immediate relief in Lower Chitral following glacial flooding, distributing over 20 food packs and conducting needs assessments in areas under the Deputy Commissioner. Post-disaster needs assessments, such as the July 2024 PDNA, identified requirements for rebuilding initiatives, focusing on resilient housing and irrigation restoration to mitigate future losses. Government-led efforts include NDMA's push for early warning systems tailored to floods and earthquakes, though implementation gaps persist due to the district's terrain. International aid, including from ReliefWeb partners, supports rapid needs analyses to prioritize sectors like agriculture and transport recovery. Economic projects in Lower Chitral aim to bolster resilience and growth through agriculture, hydropower, and infrastructure. The Chitral Area Development Project, funded by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), enhanced productivity via improved irrigation, seeds, fertilizers, and technical training, benefiting rural households in Lower Chitral's valleys. Aga Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) initiatives, such as the Shaghor micro-hydel project, provide reliable electricity to support small enterprises and reduce disaster-related outages. The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Board of Investment and Trade (KP-BOIT) plans a 40-acre economic zone in Chitral District, offering proximity to transport routes for sustainable industrial growth. The Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund's Chitral Growth Strategy identifies high-potential sub-sectors like horticulture, linking highland produce to lowland markets via informal networks to increase farmer incomes. Hydropower development, integrated with socioeconomic planning, addresses energy needs while adapting to climate impacts on water resources. These projects emphasize causal links between infrastructure investment and reduced disaster vulnerability, though challenges like remoteness limit scaling.References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/392352123_Developing_Strategic_Business_Models_for_Pakistan%27s_EP_Sector_in_a_Net-Zero_Carbon_Future_Case_Studies_on_the_Beneficiation_of_Copper_Cu_and_Antimony_Sb_Deposits_in_Lower_Chitral