Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Éliphas Lévi

View on WikipediaThis article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (April 2022) |

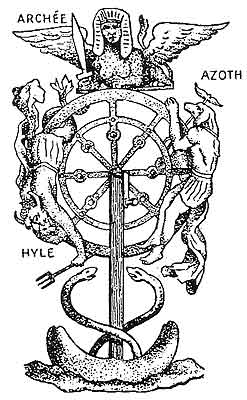

Éliphas Lévi Zahed, born Alphonse Louis Constant (8 February 1810 – 31 May 1875), was a French esotericist, poet, and writer. Initially pursuing an ecclesiastical career in the Catholic Church, he abandoned the priesthood in his mid-twenties and became a ceremonial magician. At the age of 40, he began professing knowledge of the occult.[1] He wrote over 20 books on magic, Kabbalah, alchemical studies, and occultism.

Key Information

The pen name "Éliphas Lévi" was an adaptation of his given names "Alphonse Louis" into Hebrew. Levi gained renown as an original thinker and writer, his works attracting attention in Paris and London among esotericists and artists of romantic or symbolist inspiration.[2][3] He left the Grand Orient de France (the French Masonic organization that originated Continental Freemasonry) in the belief that the original meanings of its symbols and rituals had been lost. "I ceased being a freemason, at once, because the Freemasons, excommunicated by the Pope, did not believe in tolerating Catholicism ... [and] the essence of Freemasonry is the tolerance of all beliefs."[4]

Many authors influenced Levi's political, occultic and literary development, such as the French monarchist Joseph de Maistre (whom he quotes in many parts of his Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie), Paracelsus, Robert Fludd, Swedenborg, Fabre d'Olivet, the Rosicrucians, Plato, Raymond Lull, and other esotericists.[5]

Life

[edit]Early period

[edit]Born Alphonse Louis Constant, he was the son of a shoemaker in Paris. In 1832 he entered the seminary of Saint Sulpice to study to enter the Roman Catholic priesthood. As a sub-deacon he was responsible for catechism. Later he was ordained a deacon, remaining a cleric for the rest of his life. One week before being ordained to the priesthood, he decided to leave the priestly path; however, the spirit of charity and the life he had in the seminary stayed with him through the rest of his life. Later he wrote that he had acquired an understanding of faith and science without conflicts.[6]

In 1836, on leaving the priestly path, he provoked his superiors' anger. He had committed to permanent vows of chastity and obedience as a sub-deacon and deacon, so returning to civil life was particularly painful for him; he continued to wear the clerical clothes, the cassocks, until 1844.

The possible reasons that saw Levi's departure from the Saint-Sulpice seminary, in 1836, are expressed in the following quote, by A. E. Waite: "He [Levi] seems, however, to have conceived strange views on doctrinal subjects, though no particulars are forthcoming, and, being deficient in gifts of silence, the displeasure of authority was marked by various checks, ending finally in his expulsion from the Seminary. Such is one story at least, but an alternative says more simply that he relinquished the sacerdotal career in consequence of doubts and scruples."[7]

He had to obviate extreme poverty by working as a tutor in Paris. Around 1838, he met and was influenced by the views of the mystic Simon Ganneau, and it may have been through Ganneau's meetings that he also met Flora Tristan.[8][9][10] In 1839 he entered the monastic life in the Abbey of Solesmes, but he could not maintain the discipline so he quit the monastery.

Upon returning to Paris, he wrote, La Bible de la liberté (The Bible of Liberty), which resulted in his imprisonment in August 1841.

The Eliphas Levi Circle ("(Association law 1901) was set up on April 1, 1975") gives the following summary of Levi's marriage and paternity: "At the age of 32 he met two young girls who were friends, Eugénie C and Noémie Cadiot. Despite his preference for Eugenie he also fell under the spell of Noémie whom he was obliged to marry in 1846 in order to avoid a confrontation with the girl’s father. Seven years later Noémie ran away from the marital home to join the marquis of Montferriet and in 1865 the marriage was annulled. Several children issued from this marriage, in particular twins who died shortly after birth. None of these children reached adult age, little Marie for example, who died when she was seven. Lévi had an illegitimate son with Eugénie C, born 29 September 1846, but the child never bore Lévi’s name. However he did know his father, who saw that he was educated. We know from reliable sources that the descendants of this son are living among us in France today."[11]

Writing at the beginning of the 20th century, A. E. Waite depicts Levi's marriage, perished offspring, and (possible) violation of the Saint Sulpice seminary rule, as follows:

I have failed to ascertain at what period he married Mlle. Noemy, a girl of sixteen, who became afterwards of some repute as a sculptor, but it was a runaway match and in the end she left him. It is even said that she succeeded in a nullity suit—not on the usual grounds, for she had borne him two children, who died in their early years if not during infancy, but on the plea that she was a minor, while he had taken irrevocable vows. Saint-Sulpice is, however, a seminary for secular priests who are not pledged to celibacy, though the rule of the Latin Church forbids them to enter the married state.[12]

Unexpectedly, in 1850, at the age of 40, Levi succumbed to a period of heightened financial and spiritual crisis, leading him, more profoundly, to find refuge in the milieu of mid-19th-century esotericism and the occult.[11]

Later period

[edit]In December 1851, Napoleon III organized a coup that would end the Second Republic and give rise to the Second Empire. Lévi saw the emperor as the defender of the people and the restorer of public order. In the Moniteur parisien of 1852, Lévi praised the new government's actions, but he soon became disillusioned with the rigid dictatorship and was eventually imprisoned in 1855 for publishing a polemical chanson against the Emperor. What had changed, however, was Lévi's attitude towards "the people." As early as in La Fête-Dieu and Le livre des larmes from 1845, he had been skeptical of the uneducated people's ability to emancipate themselves. Similar to the Saint-Simonians, he had adopted the theocratic ideas of Joseph de Maistre in order to call for the establishment of a "spiritual authority" led by an élite class of priests. After the disaster of 1849, he was completely convinced that the "masses" were not able to establish a harmonious order and needed instruction.[13]

Lévi's activities reflect the struggle to come to terms, both with the failure of 1848 and the tough repressions by the new government. He participated on the Revue philosophique et religieuse, founded by his old friend Fauvety, wherein he propagated his "Kabbalistic" ideas, for the first time in public, in 1855-1856 (notably using his civil name).[14]

Lévi began to write Histoire de la magie in 1860. The following year, in 1861, he published a sequel to Dogme et rituel, La clef des grands mystères ("The Key to the Great Mysteries"). In 1861 Lévi revisited London. Further magical works by Lévi include Fables et symboles ("Stories and Images"), 1862, Le sorcier de Meudon ("The Wizard of Meudon", an extended edition of two novels originally published in 1847) 1861, and La science des esprits ("The Science of Spirits"), 1865. In 1868, he wrote Le grand arcane, ou l'occultisme Dévoilé ("The Great Secret, or Occultism Unveiled"); this, however, was only published posthumously in 1898.[citation needed]

The thesis of magic propagated by Éliphas Lévi was of significant renown, especially after his death. That Spiritualism was popular on both sides of the Atlantic from the 1850s contributed to this success. However, Lévi diverged from spiritualism and criticized it, because he believed only mental images and "astral forces" persisted after an individual died, which could be freely manipulated by skilled magicians, unlike the autonomous spirits that Spiritualism posited.[15]

In regard to the purported supernatural occurrences reported by the practitioners of spiritualism, Levi was obviously credulous. He explained: "The phenomena which quite recently have perturbed America and Europe, those of table-turning and fluidic manifestations, are simply magnetic currents at the beginning of their formation, appeals on the part of Nature inviting us, for the good of humanity, to reconstitute great sympathetic and religious chains."[16]

His magical teachings were free from obvious fanaticisms, even if they remained rather obscure; and he had nothing to sell (notwithstanding his publications). He did profess himself to be: "A poor and obscure scholar [who] has found the lever of Archimedes, and he offers it to you for the good of humanity alone, asking nothing whatsoever in exchange."[16] He did not pretend to be the initiate of some ancient or fictitious secret society. He incorporated the Tarot cards into his magical system, and as a result the Tarot has been an important part of the paraphernalia of Western magicians.[17]

He had a deep impact on the magic of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and later on ex–Golden Dawn member Aleister Crowley. He was also the first to declare that a pentagram or five-pointed star with one point down and two points up represents evil, while a pentagram with one point up and two points down represents good.[citation needed] Lévi's ideas also influenced Helena Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society.[18]

As a ceremonial magus

[edit]Of his initial experience with British esotericists, in 1854, Levi wrote: "I had undertaken a journey to London, that I might escape from internal disquietude and devote myself, without interruption, to science. [...] They asked me forthwith to work wonders, as if I were a charlatan, and I was somewhat discouraged, for, to speak frankly, far from being inclined to initiate others into the mysteries of Ceremonial Magic, I had shrunk all along from its illusions and weariness. Moreover, such ceremonies necessitated an equipment which would be expensive and hard to collect. I buried myself therefore in the study of the transcendent Kabbalah, and troubled no further about English adepts."[19]

It did not take long after his arrival in England, however, before his skills as a reputed magus were earnestly courted; and Levi obliged: An elderly British woman, who, on the agreement to strictest secrecy, "rigorous amongst adepts," provided him with "a complete magical cabinet" containing the necessary paraphernalia to apply his theories to the practice of magic in England.[20]

Theory of magic

[edit]In the preface to The History of Magic, translator A. E. Waite enumerates what he believed to be the nine key tenets of magic as codified in Levi's earlier work, Doctrine and Ritual of Transcendental Magic. They are:

(1) There is a potent and real Magic, popular exaggerations of which are actually below the truth. (2) There is a formidable secret which constitutes the fatal science of good and evil. (3) It confers on many powers apparently super-human. (4) It is the traditional science of the secrets of Nature which has been transmitted to us from the Magi. (5) Initiation therein gives empire over souls to the sage and full capacity for ruling human wills. (6). Arising apparently from this science, there is one infallible, indefectible and truly catholic religion which has always existed in the world, but it is unadapted for the multitude. (7) For this reason there has come into being the exoteric religion of apologue [parable], fable and wonder-stories, which is all that is possible for the profane : it has undergone various transformations, and it is represented at this day by Latin Christianity under the obedience of Rome. (8) Its veils are valid in their symbolism, and it may be called valid for the crowd, but the doctrine of initiates is tantamount to a negation of any literal truth therein. (9) It is Magic alone which imparts true science.[21]

The three chief components of Levi's magical thesis were: Astral Light, the Will and the Imagination. Levi did not originate any of these as occult concepts.

Concerning the "Astral Light", Waite noted: "the Astral Light, which is neither more nor less than the odylic force of Baron Carl Reichenbach, as the French writer [Levi] himself admits substantially, [...]"[22] and: "This force he [Levi] usually terms the Astral Light, a name which is borrowed from Saint-Martin and the French mystics of the eighteenth century."[23]

Louis Claude de Saint-Martin had used the term "astral" to mean "psychic force"[24]

"Astral Light" was also indebted to the ideas of 18th-century proto-hypnotist, Franz Mesmer: "[Mesmer] evolved the theory of “animal magnetism.” This he held to be a fluid which pervades the universe, but is most active in the human nervous organization, and enables one man, charged with the fluid, to exert a powerful influence over another."[25]

Astral is an adjective meaning: "Connected to, consisting of, stars."[26] Levi used the term "Astral", not only as a synonym for "psychic force", but because he believed in the ancient and medieval practice of astrology. As Levi wrote himself: "Nothing is indifferent in Nature, a pebble more or less upon a road may crush or profoundly alter the fortunes of the greatest men and even of the greatest empires, much more then the position of a particular star can not be indifferent to the destinies of the child who is being, and who enters by the fact of his birth into the universal harmony of the sidereal [astrological] world."[27]

"Will" and "Imagination", as magical agents, were asserted three centuries before Levi, by Paracelsus:

The magical is a great hidden wisdom, and reason is a great open folly. No armour shields against magic for it strikes at the inward spirit of life. Of this we may rest assured, that through full and powerful imagination only can we bring the spirit of any man into an image. No conjuration, no rites are needful; circle-making and the scattering of incense are mere humbug and jugglery. The human spirit is so great a thing that no man can express it; eternal and unchangeable as God Himself is the mind of man; and could we rightly comprehend the mind of man, nothing would be impossible to us upon the earth. Through faith the imagination is invigorated and completed, for it really happens that every doubt mars its perfection. Faith must strengthen imagination, for faith establishes the will. Because man did not perfectly believe and imagine, the result is that arts are uncertain when they might be wholly certain.[28]

Whether the object of your faith be real or false, you will nevertheless obtain the same effects. Thus, if I believe in Saint Peter’s statue as I should have believed in Saint Peter himself, I shall obtain the same effects that I should have obtained from Saint Peter. But that is superstition. Faith, however, produces miracles; and whether it is a true or a false faith, it will always produce the same wonders.[29]

Eliphas Levi cautioned: "The operations of [magic] science are not devoid of danger. Their result may be madness for those who are not established on the base of the supreme, absolute, and infallible reason. They may over-excite the nervous system, producing terrible and incurable diseases."[30] "Let those, therefore, who seek in magic the means to satisfy their passions, pause in that deadly path, where they will find nothing but death or madness. This is the significance of the vulgar tradition that the devil finished sooner or later by strangling the sorcerers."[31]

Socialist background

[edit]It was long believed that the socialist Constant disappeared with the demise of the Second Republic and gave way to the occultist Éliphas Lévi. However, according to historian of religions Julian Strube, who wrote his doctoral dissertation on Constant, this narrative was constructed at the end of the 19th century in occultist circles and was uncritically adopted by later scholars. Strube argues that Constant not only developed his occultism as a direct consequence of his socialist and post-clergical ideas, but he continued to propagate the realization of socialism throughout his entire life.[32]

According to the occultist Papus (Gérard Encausse) and the occultist biographer Paul Chacornac, Constant's turn to occultism was the result of an "initiation" by the eccentric Polish expatriate Józef Maria Hoene-Wroński. The two did know each other, as evidenced in Constant's 6 January 1853 letter to Hoene-Wroński, thanking him for including one of Constant's articles in Hoené-Wroński's 1852 work, Historiosophie ou science de l'histoire. In the letter Constant expresses his admiration for Hoené-Wroński's "still underappreciated genius" and calls himself his "sincere admirer and devoted disciple."[33] Nonetheless, Strube argues that Wronski's influence had been brief, between 1852 and 1853, and superficial. He criticizes Papus and his companions' research based on Papus' attempts to contact Constant on 11 January 1886–11 years after Constant's death.[34]

Later on, the construction of a specifically French esoteric tradition, in which Constant was to form a crucial link, perpetuated this idea of a clear rupture between the socialist Constant and the occultist Lévi. Strube in 2016 wrote that a different narrative was developed independently by Arthur Edward Waite, who was a near contemporary of Lévi. Strube opined that A. E. Waite knew insufficient details of Constant's life.[35]

Furthermore, Strube proposes that Lévi contemplated "magic" as a new order—an ideology (potentially a politically useful superstition) by which a new hierarchy would be articulated, as he interpret from Levi's statement: "Hereunto therefore we have made it plain, as we believe, that our Magic is opposed to the goetic and necromantic kinds. It is at once an absolute science and religion, which should not indeed destroy and absorb all opinions and all forms of worship, but should regenerate and direct them by reconstituting the circle of initiates, and thus providing the blind masses with wise and clear-seeing leaders."[36] Strube argues that "A journey to London that Lévi made in May 1854, did not cause his preoccupation with magic", and that "even though Lévi professed involvement in magical ritual. Instead, it was the aforementioned socialist-magnetistic dialectic that compassed Lévi's interest in magic."[37] Despite so, it is clear that Lévi's statement limits itself to magic and its kinds, where Lévi proposes to have merged science and religion and promotes his own methods by claiming to have applied a scientific approach in his research, contrasting it against the Goetic and Necromantic methods.

Gallery

[edit]Selected writings

[edit]- Lévi, Éliphas (1841a). La Bible de la liberté [The Bible of Liberty].

- Lévi, Éliphas (1841b). Doctrines religieuses et sociales [Religious and Social Doctrines].

- Lévi, Éliphas (1841c). L'assomption de la femme [The Assumption of Woman].

- Lévi, Éliphas (1844). La mère de Dieu [The Mother of God].

- Lévi, Éliphas (1845). Le livre des larmes [The Book of Tears].

- Lévi, Éliphas (1848). Le testament de la liberté [The Testament of Liberty].

- Lévi, Éliphas (1854–1856). Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie [The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic]. Includes material on alchemy[38]

- Lévi, Éliphas (1860). Histoire de la magie [The History of Magic].

- Lévi, Éliphas (1861). La clef des grands mystères [The Key to the Great Mysteries].

- Lévi, Éliphas (1862). Fables et symboles [Stories and Symbols].

- Lévi, Éliphas (1865). La science des esprits [The Science of Spirits]. Paris: Germer Baillière, Libraire-éditeur.

- Lévi, Éliphas (1868). Le grand arcane, ou l'occultisme dévoilé [The Great Secret, or Occultism Unveiled].

- Lévi, Éliphas (1894). Le livre des splendeurs [The Book of Splendours].

- Lévi, Éliphas (1895). Clefs majeures et clavicules de Salomon [Major Keys and Minor Keys of Solomon].

- Lévi, Éliphas (1896). The Magical Ritual of the Sanctum Regnum.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ McIntosh 1972.

- ^ Juin 1972, p. 16.

- ^ Mercier 1969, p. 62.

- ^ Chacornac Frères 2001.

- ^ Levi 1896a, p. 34.

- ^ Levi 1896a, p. 30.

- ^ Levi 1922, p. viii.

- ^ Andrews 2006, pp. 40–41, 95, 102.

- ^ Grogan 2002, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Bertin 1995, p. 53.

- ^ a b Buisset n.d.

- ^ Levi 1922, pp. viii–ix.

- ^ Strube 2016a, pp. 418–426.

- ^ Strube 2016a, pp. 470–488.

- ^ Josephson-Storm 2017, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Levi 1896a, p. 56.

- ^ Josephson 2013.

- ^ Josephson-Storm 2017, p. 116.

- ^ Levi 1896a, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Levi 1896a, pp. 64–67.

- ^ Levi 1922, p. x-xi.

- ^ Levi 1922, p. xii.

- ^ Waite 1886, p. xxxvi.

- ^ Waite 1922, p. 18.

- ^ Hudson 1893, p. 84.

- ^ Oxford Illustrated Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1986. p. 44.

- ^ Waite 1891, p. 163.

- ^ Gordon 2001, p. 958.

- ^ Hudson 1893, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Waite 1886, p. 24.

- ^ Waite 1886, p. 26.

- ^ Strube 2016b, p. 21.

- ^ Prinke 2013, p. 133.

- ^ Strube 2016a, pp. 426–438.

- ^ Strube 2016a, pp. 590–618.

- ^ Levi 1896a, p. 16.

- ^ Strube 2016a, pp. 455–470.

- ^ Waite 2013, p. 33ff.

Works cited

[edit]- Andrews, Naomi Judith (2006). Socialism's Muse: Gender in the Intellectual Landscape of French Romantic Socialism.

- Bertin, Francis (1995). Esotérisme et socialisme.

- Chacornac Frères (2001) [1926]. "Éliphas Lévi was a freemason—briefly". Éliphas Lévi, rénovateur de l'occultisme en France (1810-1875), Paul Chacornac (1884-1964) (in French). Translated by Trevor W. McKeown. Paris: Librairie Génerale des Sciences Occultes. Archived from the original on 18 December 2001 – via Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon.

- Buisset, Christiane (n.d.). Eliphas Lévi: sa vie, son œuvre, ses pensées [Eliphas Lévi: His Life, His Work, His Thought]. de la Maisnie, out of print.

- Gordon, Melton J., ed. (2001). Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. Vol. 2 (5th ed.). Michigan: Gale Group.

- Grogan, Susan (2002). Flora Tristan: Life Stories.

- Hudson, Thomson (1893). Law Of Psychic Phenomena. Chicago: A. C. McClurg and Co.

- Josephson, Jason Ānanda (May 2013). "God's Shadow: Occluded Possibilities in the Genealogy of Religion". History of Religions. 52 (4): 321. doi:10.1086/669644. JSTOR 10.1086/669644. S2CID 170485577.

- Josephson-Storm, Jason (2017). The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-40336-6.

- Juin, Hubert (1972). Écrivains de l'avant-siècle (in French). Paris: Seghers.

- Levi, Eliphas (1896a). Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magi Part I: The Doctrine of Transcendental Magic. Translated by A. E. Waite. England: Rider & Company.

- Levi, Eliphas (1896b). The Magical Ritual of the Sanctum Regnum. Translated by W. Wynn Westcott. London: George Redway.

- Levi, Eliphas (1922). The History of Magic. Translated by A. E. Waite (2nd ed.). London: William Rider & Son Ltd.

- McIntosh, Christopher (1972). Éliphas Lévi and the French Occult Revival.

- Mercier, Alain (1969). Les Sources ésotériques et occultes de la poésie symboliste (1870-1914) (in French). Vol. 1: Le symbolisme français. A.-G. Nizet.

- Prinke, Rafał T. (2013). Wysocka, Barbara (ed.). "Uczeń Wrońskiego - Éliphas Lévi w kręgu polskich mesjanistów" [Student of Wroński - Éliphas Lévi in the circle of Polish messianists]. Pamiętnik Biblioteki Kórnickiej, Zeszyt 30 [Diary of the Kórnik Library, Book 30] (in Polish).

- Strube, Julian (2016a). Sozialismus, Katholizismus und Okkultismus im Frankreich des 19. Jahrhunderts: Die Genealogie der Schriften von Eliphas Lévi. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110478105.

- Strube, Julian (29 March 2016b). "Socialist religion and the emergence of occultism: a genealogical approach to socialism and secularization in 19th-century France". Religion. 46 (3): 359–388. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2016.1146926. ISSN 0048-721X. S2CID 147626697.

- Waite, A. E. (1886). The Mysteries Of Magic. London: George Redway.

- Waite, A. E. (1891). The Occult Sciences. London: Keagan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd.

- Waite, A. E. (1922). Saint-Martin, The French Mystic. London: William Rider & Son Ltd.

- Waite, A. E. (2013). The Secret Tradition in Alchemy: Its Development and Records. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1136182921.

Further reading

[edit]- Bowman, Frank Paul (1969). Eliphas Lévi, visionnaire romantique (in French). Presses Universitaires de France.

- Chacornac, Paul (1926). Eliphas Lévi: Rénovateur de l'Occultisme en France (in French). Chacornac frères.

- Mercier, Alain (1974). Eliphas Lévi et la pensée magique au XIXe siècle Alain Mercier (in French). Seghers.