Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Clergy

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the terms used for individual clergy are clergyman, clergywoman, clergyperson, churchman, cleric, ecclesiastic, and vicegerent while clerk in holy orders has a long history but is rarely used.[citation needed]

In Christianity, the specific names and roles of the clergy vary by denomination and there is a wide range of formal and informal clergy positions, including deacons, elders, priests, bishops, cardinals, preachers, pastors, presbyters, ministers, and the pope.

In Islam, a religious leader is often formally or informally known as an imam, caliph, qadi, mufti, sheikh, mullah, muezzin, and ulema.

In the Jewish tradition, a religious leader is often a rabbi (teacher) or hazzan (cantor).

Etymology

[edit]The word cleric comes from the ecclesiastical Latin Clericus, for those belonging to the priestly class. In turn, the source of the Latin word is from the Ecclesiastical Greek Klerikos (κληρικός), meaning appertaining to an inheritance, in reference to the fact that the Levitical priests of the Old Testament had no inheritance except the Lord.[1] "Clergy" is from two Old French words, clergié and clergie, which refer to those with learning and derive from Medieval Latin clericatus, from Late Latin clericus (the same word from which "cleric" is derived).[2] "Clerk", which used to mean one ordained to the ministry, also derives from clericus. In the Middle Ages, reading and writing were almost exclusively the domain of the priestly class, and this is the reason for the close relationship of these words.[3] Within Christianity, especially in Eastern Christianity and formerly in Western Roman Catholicism, the term cleric refers to any individual who has been ordained, including deacons, priests, and bishops.[4] In Latin Catholicism, the tonsure was a prerequisite for receiving any of the minor orders or major orders before the tonsure, minor orders, and the subdiaconate were abolished following the Second Vatican Council.[5] Now, the clerical state is tied to reception of the diaconate.[6] Minor Orders are still given in the Eastern Catholic Churches, and those who receive those orders are 'minor clerics.'[7]

The use of the word cleric is also appropriate for Eastern Orthodox minor clergy who are tonsured in order not to trivialize orders such as those of Reader in the Eastern Church, or for those who are tonsured yet have no minor or major orders. It is in this sense that the word entered the Arabic language, most commonly in Lebanon from the French, as kleriki (or, alternatively, cleriki) meaning "seminarian". This is all in keeping with Eastern Orthodox concepts of clergy, which still include those who have not yet received, or do not plan to receive, the diaconate.

A priesthood is a body of priests, shamans, or oracles who have special religious authority or function. The term priest is derived from the Greek presbyter (πρεσβύτερος, presbýteros, elder or senior), but is often used in the sense of sacerdos in particular, i.e., for clergy performing ritual within the sphere of the sacred or numinous communicating with the gods on behalf of the community.

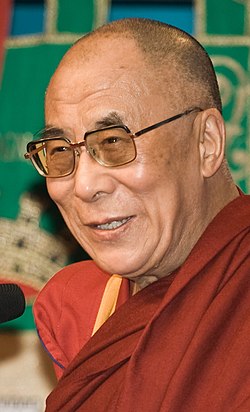

Buddhism

[edit]

Buddhist clergy are often collectively referred to as the Sangha, and consist of various orders of male and female monks (originally called bhikshus and bhikshunis respectively). This diversity of monastic orders and styles was originally one community founded by Gautama Buddha during the 5th century BC living under a common set of rules (called the Vinaya). According to scriptural records, these celibate monks and nuns in the time of the Buddha lived an austere life of meditation, living as wandering beggars for nine months out of the year and remaining in retreat during the rainy season (although such a unified condition of Pre-sectarian Buddhism is questioned by some scholars). However, as Buddhism spread geographically over time—encountering different cultures, responding to new social, political, and physical environments—this single form of Buddhist monasticism diversified. The interaction between Buddhism and Tibetan Bon led to a uniquely Tibetan Buddhism, within which various sects, based upon certain teacher-student lineages arose. Similarly, the interaction between Indian Buddhist monks (particularly of the Southern Madhyamika School) and Chinese Confucian and Taoist monks from c200-c900AD produced the distinctive Ch'an Buddhism. Ch'an, like the Tibetan style, further diversified into various sects based upon the transmission style of certain teachers (one of the most well known being the 'rapid enlightenment' style of Linji Yixuan), as well as in response to particular political developments such as the An Lushan Rebellion and the Buddhist persecutions of Emperor Wuzong. In these ways, manual labour was introduced to a practice where monks originally survived on alms; layers of garments were added where originally a single thin robe sufficed; etc. This adaptation of form and roles of Buddhist monastic practice continued after the transmission to Japan. For example, monks took on administrative functions for the Emperor in particular secular communities (registering births, marriages, deaths), thereby creating Buddhist 'priests'. Again, in response to various historic attempts to suppress Buddhism (most recently during the Meiji Era), the practice of celibacy was relaxed and Japanese monks allowed to marry. This form was then transmitted to Korea, during later Japanese occupation,[8] where celibate and non-celibate monks today exist in the same sects. (Similar patterns can also be observed in Tibet during various historic periods multiple forms of monasticism have co-existed such as "ngagpa" lamas, and times at which celibacy was relaxed). As these varied styles of Buddhist monasticism are transmitted to Western cultures, still more new forms are being created.

In general, the Mahayana schools of Buddhism tend to be more culturally adaptive and innovative with forms, while Theravada schools (the form generally practiced in Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka) tend to take a much more conservative view of monastic life, and continue to observe precepts that forbid monks from touching women or working in certain secular roles. This broad difference in approach led to a major schism among Buddhist monastics in about the 4th century BCE, creating the Early Buddhist Schools.

While female monastic (bhikkhuni) lineages existed in most Buddhist countries at one time, the Theravada lineages of Southeast Asia died out during the 14th-15th Century AD. As there is some debate about whether the bhikkhuni lineage (in the more expansive Vinaya forms) was transmitted to Tibet, the status and future of female Buddhist clergy in this tradition is sometimes disputed by strict adherents to the Theravadan style. Some Mahayana sects, notably in the United States (such as San Francisco Zen Center) are working to reconstruct the female branches of what they consider a common, interwoven lineage.[9]

The diversity of Buddhist traditions makes it difficult to generalize about Buddhist clergy. In the United States, Pure Land priests of the Japanese diaspora serve a role very similar to Protestant ministers of the Christian tradition. Meanwhile, reclusive Theravada forest monks in Thailand live a life devoted to meditation and the practice of austerities in small communities in rural Thailand- a very different life from even their city-dwelling counterparts, who may be involved primarily in teaching, the study of scripture, and the administration of the nationally organized (and government sponsored) Sangha. In the Zen traditions of China, Korea and Japan, manual labor is an important part of religious discipline; meanwhile, in the Theravada tradition, prohibitions against monks working as laborers and farmers continue to be generally observed.

Currently in North America, there are both celibate and non-celibate clergy in a variety of Buddhist traditions from around the world. In some cases, they are forest dwelling monks of the Theravada tradition; in other cases, they are married clergy of a Japanese Zen lineage and may work a secular job in addition to their role in the Buddhist community. There is also a growing realization that traditional training in ritual and meditation as well as philosophy may not be sufficient to meet the needs and expectations of American lay people. Some communities have begun exploring the need for training in counseling skills as well. Along these lines, at least two fully accredited Master of Divinity programs are currently available: one at Naropa University in Boulder, CO and one at the University of the West in Rosemead, CA.

Titles for Buddhist clergy include:

In Theravada:

- Acharya

- Ajahn

- Anagarika

- Ayya

- Bhante

- Dasa sil mata

- Luang Por

- Maechi or Mae chee

- Phra

- Sayadaw

- Sikkhamānā

- Thilashin

In Mahayana:

In Vajrayana:

Christianity

[edit]In general, Christian clergy are ordained; that is, they are set apart for specific ministry in religious rites. Others who have definite roles in worship but who are not ordained (e.g., laypeople acting as acolytes) are generally not considered clergy, even though they may require some sort of official approval to exercise these ministries.

Types of clerics are distinguished from offices, even when the latter are commonly or exclusively occupied by clerics. A Roman Catholic cardinal, for instance, is almost without exception a cleric, but a cardinal is not a type of cleric. An archbishop is not a distinct type of cleric, but is simply a bishop who occupies a particular position with special authority. Conversely, a youth minister at a parish may or may not be a cleric. Different churches have different systems of clergy, though churches with similar polity have similar systems.

Anglicanism

[edit]

In Anglicanism, clergy consist of the orders of deacons, priests (presbyters), and bishops in ascending order of seniority. Canon, archdeacon, archbishop and the like are specific positions within these orders. Bishops are typically overseers, presiding over a diocese composed of many parishes, with an archbishop presiding over a province in most, which is a group of dioceses. A parish (generally a single church) is looked after by one or more priests, although one priest may be responsible for several parishes. New clergy are first ordained as deacons. Those seeking to become priests are usually ordained to the priesthood around a year later. Since the 1960s some Anglican churches have reinstituted the permanent diaconate, in addition to the transitional diaconate, as a ministry focused on bridges the church and the world, especially ministry to those on the margins of society.

For a short period of history before the ordination of women as deacons, priests and bishops began within Anglicanism, women could be deaconesses. Although they were usually considered having a ministry distinct from deacons they often had similar ministerial responsibilities.

In Anglicanism all clergy are permitted to marry. In most national churches women may become deacons or priests, but while fifteen out of 38 national churches allow for the consecration of women as bishops, only five have ordained any. Celebration of the Eucharist is reserved for priests and bishops.

National Anglican churches are presided over by one or more primates or metropolitans (archbishops or presiding bishops). The senior archbishop of the Anglican Communion is the Archbishop of Canterbury, who acts as leader of the Church of England and 'first among equals' of the primates of all Anglican churches.

Being a deacon, priest or bishop is considered a function of the person and not a job. When priests retire they are still priests even if they no longer have any active ministry. However, they only hold the basic rank after retirement. Thus a retired archbishop can only be considered a bishop (though it is possible to refer to "Bishop John Smith, the former Archbishop of York"), a canon or archdeacon is a priest on retirement and does not hold any additional honorifics.

For the forms of address for Anglican clergy, see Forms of address in the United Kingdom.

-

Sir George Fleming, 2nd Baronet, British churchman.

-

Charles Wesley Leffingwell, Episcopal priest.

Baptist

[edit]The Baptist tradition only recognizes two ordained positions in the church as being the elders (pastors) and deacons as outlined in the third chapter of I Timothy[10] in the Bible.

Catholic Church

[edit]

Ordained clergy in the Catholic Church are either deacons, priests, or bishops belonging to the diaconate, the presbyterate, or the episcopate, respectively. Among bishops, some are metropolitans, archbishops, or patriarchs. The pope is the bishop of Rome, the supreme and universal hierarch of the Church, and his authorization is now required for the ordination of all Roman Catholic bishops. With rare exceptions, cardinals are bishops, although it was not always so; formerly, some cardinals were people who had received clerical tonsure, but not Holy Orders. Secular clergy are ministers, such as deacons and priests, who do not belong to a religious institute and live in the world at large, rather than a religious institute (saeculum). The Holy See supports the activity of its clergy by the Congregation for the Clergy ([1]), a dicastery of Roman curia.

Canon Law indicates (canon 207) that "[b]y divine institution, there are among the Christian faithful in the Church sacred ministers who in law are also called clerics; the other members of the Christian faithful are called lay persons".[11] This distinction of a separate ministry was formed in the early times of Christianity; one early source reflecting this distinction, with the three ranks or orders of bishop, priest and deacon, is the writings of Saint Ignatius of Antioch.

Holy Orders is one of the Seven Sacraments, enumerated at the Council of Trent, that the Magisterium considers to be of divine institution. In the Catholic Church, only men are permitted to be clerics.[12]

In the Latin Church before 1972, tonsure admitted someone to the clerical state, after which he could receive the four minor orders (ostiary, lectorate, order of exorcists, order of acolytes) and then the major orders (subdiaconate, diaconate, presbyterate, and finally the episcopate), which according to Roman Catholic doctrine is "the fullness of Holy Orders". Since 1972 the minor orders and the subdiaconate have been replaced by lay ministries and clerical tonsure no longer takes place, except in some Traditionalist Catholic groups, and the clerical state is acquired, even in those groups, by Holy Orders.[13] In the Latin Church the initial level of the three ranks of Holy Orders is that of the diaconate. In addition to these three orders of clerics, some Eastern Catholic, or "Uniate", Churches have what are called "minor clerics".[14]

Members of institutes of consecrated life and societies of apostolic life are clerics only if they have received Holy Orders. Thus, unordained monks, friars, nuns, and religious brothers and sisters are not part of the clergy.

The Code of Canon Law and the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches prescribe that every cleric must be enrolled or "incardinated" in a diocese or its equivalent (an apostolic vicariate, territorial abbey, personal prelature, etc.) or in a religious institute, society of apostolic life or secular institute.[15][14] The need for this requirement arose because of the trouble caused from the earliest years of the Church by unattached or vagrant clergy subject to no ecclesiastical authority and often causing scandal wherever they went.[16]

Current canon law prescribes that to be ordained a priest, an education is required of two years of philosophy and four of theology, including study of dogmatic and moral theology, the Holy Scriptures, and canon law have to be studied within a seminary or an ecclesiastical faculty at a university.[17][18]

Clerical celibacy is a requirement for almost all clergy in the predominant Latin Church, with the exception of deacons who do not intend to become priests. Exceptions are sometimes admitted for ordination to transitional diaconate and priesthood on a case-by-case basis for married clergymen of other churches or communities who become Catholics, but consecration of already married men as bishops is excluded in both the Latin and Eastern Catholic Churches (see personal ordinariate). Clerical marriage is not allowed and therefore, if those for whom in some particular Church celibacy is optional (such as permanent deacons in the Latin Church) wish to marry, they must do so before ordination. Eastern Catholic Churches while allowing married men to be ordained, do not allow clerical marriage after ordination: their parish priests are often married, but must marry before being ordained to the priesthood.[19] Eastern Catholic Churches require celibacy only for bishops.

Eastern Orthodoxy

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

The Eastern Orthodox Church has three ranks of holy orders: bishop, priest, and deacon. These are the same offices identified in the New Testament and found in the Early Church, as testified by the writings of the Holy Fathers. Each of these ranks is ordained through the Sacred Mystery (sacrament) of the laying on of hands (called cheirotonia) by bishops. Priests and deacons are ordained by their own diocesan bishop, while bishops are consecrated through the laying on of hands of at least three other bishops.

Within each of these three ranks there are found a number of titles. Bishops may have the title of archbishop, metropolitan, and patriarch, all of which are considered honorifics. Among the Orthodox, all bishops are considered equal, though an individual may have a place of higher or lower honor, and each has his place within the order of precedence. Priests (also called presbyters) may (or may not) have the title of archpriest, protopresbyter (also called "protopriest", or "protopope"), hieromonk (a monk who has been ordained to the priesthood) archimandrite (a senior hieromonk) and hegumen (abbot). Deacons may have the title of hierodeacon (a monk who has been ordained to the deaconate), archdeacon or protodeacon.

The lower clergy are not ordained through cheirotonia (laying on of hands) but through a blessing known as cheirothesia (setting-aside). These clerical ranks are subdeacon, reader and altar server (also known as taper-bearer). Some churches have a separate service for the blessing of a cantor.

Ordination of a bishop, priest, deacon or subdeacon must be conferred during the Divine Liturgy (Eucharist)—though in some churches it is permitted to ordain up through deacon during the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts—and no more than a single individual can be ordained to the same rank in any one service. Numerous members of the lower clergy may be ordained at the same service, and their blessing usually takes place during the Little Hours prior to Liturgy, or may take place as a separate service. The blessing of readers and taper-bearers is usually combined into a single service. Subdeacons are ordained during the Little Hours, but the ceremonies surrounding his blessing continue through the Divine Liturgy, specifically during the Great Entrance.

Bishops are usually drawn from the ranks of the archimandrites, and are required to be celibate; however, a non-monastic priest may be ordained to the episcopate if he no longer lives with his wife (following Canon XII of the Quinisext Council of Trullo)[20] In contemporary usage such a non-monastic priest is usually tonsured to the monastic state, and then elevated to archimandrite, at some point prior to his consecration to the episcopacy. Although not a formal or canonical prerequisite, at present bishops are often required to have earned a university degree, typically but not necessarily in theology.

Usual titles are Your Holiness for a patriarch (with Your All-Holiness reserved for the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople), Your Beatitude for an archbishop/metropolitan overseeing an autocephalous Church, Your Eminence for an archbishop/metropolitan generally, Master or Your Grace for a bishop and Father for priests, deacons and monks,[21] although there are variations between the various Orthodox Churches. For instance, in Churches associated with the Greek tradition, while the Ecumenical Patriarch is addressed as "Your All-Holiness", all other Patriarchs (and archbishops/metropolitans who oversee autocephalous Churches) are addressed as "Your Beatitude".[22]

Orthodox priests, deacons, and subdeacons must be either married or celibate (preferably monastic) prior to ordination, but may not marry after ordination. Remarriage of clergy following divorce or widowhood is forbidden. Married clergy are considered as best-suited to staff parishes, as a priest with a family is thought better qualified to counsel his flock.[23] It has been common practice in the Russian tradition for unmarried, non-monastic clergy to occupy academic posts.

Methodism

[edit]In the Methodist churches, candidates for ordination are "licensed" to the ministry for a period of time (typically one to three years) prior to being ordained.[24] This period typically is spent performing the duties of ministry under the guidance, supervision, and evaluation of a more senior, ordained minister. In some denominations, however, licensure is a permanent, rather than a transitional state for ministers assigned to certain specialized ministries, such as music ministry or youth ministry.

Latter-day Saints

[edit]The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) has no dedicated clergy, and is governed instead by a system of lay priesthood leaders. Locally, unpaid and part-time priesthood holders lead the church; the worldwide church is supervised by full-time general authorities, some of whom receive modest living allowances.[25][26] No formal theological training is required for any position. The church believes that all of its leaders are called by revelation and the laying on of hands by one who holds authority. The church also believes that Jesus Christ stands at the head of the church and leads the church through revelation given to the President of the Church, the First Presidency, and Twelve Apostles, all of whom are recognized as prophets, seers, and revelators and have lifetime tenure. Below these men in the hierarchy are quorums of seventy, which are assigned geographically over the areas of the church. Locally, the church is divided into stakes; each stake has a president, who is assisted by two counselors and a high council. The stake is made up of several individual congregations, which are called "wards" or "branches". Wards are led by a bishop and his counselors and branches by a president and his counselors. Local leaders serve in their positions until released by their supervising authorities.[27]

Generally, all worthy males age 12 and above receive the priesthood. Youth age 12 to 18 are ordained to the Aaronic priesthood as deacons, teachers, or priests, which authorizes them to perform certain ordinances and sacraments. Adult males are ordained to the Melchizedek priesthood, as elders, seventies, high priests, or patriarchs in that priesthood, which is concerned with spiritual leadership of the church. Although the term "clergy" is not typically used in the LDS Church, it would most appropriately apply to local bishops and stake presidents. Merely holding an office in the priesthood does not imply authority over other church members or agency to act on behalf of the entire church.

Lutheranism

[edit]

From a religious standpoint there is only one order of clergy in the Lutheran church, namely the office of pastor. This is stated in the Augsburg Confession, article 14.[28] Some Lutheran churches, like the state churches of Scandinavia, refer to this office as priest.

However, for practical and historical reasons, Lutheran churches tend to have different roles of pastors or priests, and a clear hierarchy. Some pastors are functioning as deacons or provosts, others as parish priests and yet some as bishops and even archbishops. Lutherans have no principal aversion against having a pope as the leading bishop. But the Roman Catholic view of the papacy is considered antichristian.[29]

In many European churches where Lutheranism was the state religion, the clergy were also civil servants, and their responsibilities extended well beyond spiritual leadership, encompassing government administration, education, and the implementation of government policies. Government administration was organized around the church's parishes. In rural parishes the parish priest tended to be the foremost government official. In more important parishes or cities a bishop or governor would outrank parish priests.

The Book of Concord, a compendium of doctrine for the Lutheran Churches allows ordination to be called a sacrament.[30]

Reformed

[edit]The Presbyterian Church (USA) ordains two types of presbyters or elders, teaching (pastor) and ruling (leaders of the congregation which form a council with the pastors). Teaching elders are seminary trained and ordained as a presbyter and set aside on behalf of the whole denomination to the ministry of Word and Sacrament. Ordinarily, teaching elders are installed by a presbytery as pastor of a congregation. Ruling elders, after receiving training, may be commissioned by a presbytery to serve as a pastor of a congregation, as well as preach and administer sacraments.[31]

In Congregationalist churches, local churches are free to hire (and often ordain) their own clergy, although the parent denominations typically maintain lists of suitable candidates seeking appointment to local church ministries and encourage local churches to consider these individuals when filling available positions.

Hinduism

[edit]

A Hindu priest may refer to either of the following:

- A pujari (IAST: Pūjārī) or an archaka is a Hindu temple priest.[32]

- A purohita (IAST: Purōhita) officiates and performs rituals and ceremonies, and is usually linked to a specific family or, historically, a dynasty.[33]

- A sadhu (IAST: Sādhu) is an ascetic who renounced his worldly life and devoted to liberation from cycle of life of birth, death and rebirth. A Sadhu is also called Sannyasa. Ascetics are both male and female. Their duty is preach religion to people.

- A brahmachari is a person initiated into monasticism. He is a trainee and his duty is to learn and preach scriptures to people. Female initiate is called Brahmacharini.[34]

Traditionally, priests have predominantly come from the Brahmana class, whose male members are designated for the function in the Hindu texts.[35][36]

Hindu priests are known to perform prayer services, often referred to as puja. Priests are identified as pandits or pujaris amongst the devotees.[37] Braja Kishore Goswami "Yuvaaraj" is one such famous spiritual leader of the Hindu religion.

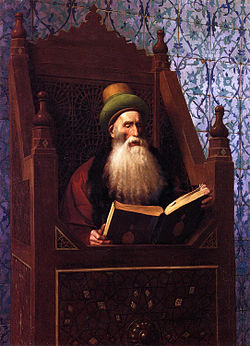

Islam

[edit]Islam, like Judaism, has no clergy in the sacerdotal sense; there is no institution resembling the Christian priesthood. Islamic religious leaders do not "serve as intermediaries between mankind and God",[38] have "process of ordination",[39] nor "sacramental functions".[38] They have been said to resemble more rabbis, serving as "exemplars, teachers, judges, and community leaders", providing religious rules to the pious on "even the most minor and private" matters.[38]

The title mullah (a Persian variation of the Arabic maula, "master"), commonly translated "cleric" in the West and thought to be analogous to "priest" or "rabbi", is a title of address for any educated or respected figure, not even necessarily (though frequently) religious. The title sheikh ("elder") is used similarly.

Most of the religious titles associated with Islam are scholastic or academic in nature: they recognize the holder's exemplary knowledge of the theory and practice of ad-dín (religion), and do not confer any particular spiritual or sacerdotal authority. The most general such title is `alim (pl. `ulamah), or "scholar". This word describes someone engaged in advanced study of the traditional Islamic sciences (`ulum) at an Islamic university or madrasah jami`ah. A scholar's opinions may be valuable to others because of his/her knowledge in religious matters; but such opinions should not generally be considered binding, infallible, or absolute, as the individual Muslim is directly responsible to God for their own religious beliefs and practice.

There is no sacerdotal office corresponding to the Christian priest or Jewish kohen, as there is no sacrificial rite of atonement comparable to the Eucharist or the Korban. Ritual slaughter or dhabihah, including the qurban at `Idu l-Ad'ha, may be performed by any adult Muslim who is physically able and properly trained. Professional butchers may be employed, but they are not necessary; in the case of the qurban, it is especially preferable to slaughter one's own animal if possible.[40]

Sunni

[edit]

The nearest analogue among Sunni Muslims to the parish priest or pastor, or to the "pulpit rabbi" of a synagogue, is called the imam khatib. This compound title is merely a common combination of two elementary offices: leader (imam) of the congregational prayer, which in most mosques is performed at the times of all daily prayers; and preacher (khatib) of the sermon or khutba of the obligatory congregational prayer at midday every Friday. Although either duty can be performed by anyone who is regarded as qualified by the congregation, at most well-established mosques imam khatib is a permanent part-time or full-time position. He may be elected by the local community, or appointed by an outside authority—e.g., the national government, or the waqf that sustains the mosque. There is no ordination as such; the only requirement for appointment as an imam khatib is recognition as someone of sufficient learning and virtue to perform both duties on a regular basis, and to instruct the congregation in the basics of Islam.

The title hafiz (lit. "preserver") is awarded to one who has memorized the entire Qur'an, often by attending a special course for the purpose; the imam khatib of a mosque is frequently (though not always) a hafiz.

There are several specialist offices pertaining to the study and administration of Islamic law or shari`ah. A scholar with a specialty in fiqh or jurisprudence is known as a faqih. A qadi is a judge in an Islamic court. A mufti is a scholar who has completed an advanced course of study which qualifies him to issue judicial opinions or fatawah.

Shia

[edit]

In modern Shia Islam, scholars play a more prominent role in the daily lives of Muslims than in Sunni Islam; and there is a hierarchy of higher titles of scholastic authority, such as Ayatollah. Traditionally a more complex title has been used in Twelver Shi`ism, namely marjaʿ at-taqlid. Marjaʿ (pl. marajiʿ ) means "source", and taqlid refers to religious emulation or imitation. Lay Shi`ah must identify a specific marjaʿ whom they emulate, according to his legal opinions (fatawah) or other writings. On several occasions, the Marjaʿiyyat (community of all marajiʿ ) has been limited to a single individual, in which case his rulings have been applicable to all those living in the Twelver Shi'ah world. Of broader importance has been the role of the mujtahid, a cleric of superior knowledge who has the authority to perform ijtihad (independent judgment). Mujtahids are few in number, but it is from their ranks that the marajiʿ at-taqlid are drawn. However these titles are more related to scholarly rank and piety than a hierarchy like that of a priesthood.

Sufism

[edit]The spiritual guidance function known in many Christian denominations as "pastoral care" is fulfilled for many Muslims by a murshid ("guide"), a master of the spiritual sciences and disciplines known as tasawuf or Sufism. Sufi guides are commonly styled Shaikh in both speaking and writing; in North Africa they are sometimes called marabouts. They are traditionally appointed by their predecessors, in an unbroken teaching lineage reaching back to Muhammad. (The lineal succession of guides bears a superficial similarity to Christian ordination and apostolic succession, or to Buddhist dharma transmission; but a Sufi guide is regarded primarily as a specialized teacher and Islam denies the existence of an earthly hierarchy among believers.)

Muslims who wish to learn Sufism dedicate themselves to a murshid's guidance by taking an oath called a bai'ah. The aspirant is then known as a murid ("disciple" or "follower"). A murid who takes on special disciplines under the guide's instruction, ranging from an intensive spiritual retreat to voluntary poverty and homelessness, is sometimes known as a dervish.

During the Islamic Golden Age, it was common for scholars to attain recognized mastery of both the "exterior sciences" (`ulum az-zahir) of the madrasahs as well as the "interior sciences" (`ulum al-batin) of Sufism. Al-Ghazali and Rumi are two notable examples.

Ahmadiyya

[edit]The highest office an Ahmadi can hold is that of Khalifatu l-Masih. Such a person may appoint amirs who manage regional areas.[41] The consultative body for Ahmadiyya is called the Majlis-i-Shura, which ranks second in importance to the Khalifatu l-Masih.[42] However, the Ahmadiyya community is declared as non-Muslims by many mainstream Muslims and they reject the messianic claims of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad.

Judaism

[edit]

Rabbinic Judaism does not have clergy as such, although according to the Torah there is a tribe of priests known as the Kohanim who were leaders of the religion up to the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 AD when most Sadducees were wiped out; each member of the tribe, a Kohen had priestly duties, many of which centered around the sacrificial duties, atonement and blessings of the Israelite nation. Today, Jewish Kohanim know their status by family tradition, and still offer the priestly blessing during certain services in the synagogue and perform the Pidyon haben (redemption of the first-born son) ceremony.

Since the time of the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, the religious leaders of Judaism have often been rabbis, who are technically scholars in Jewish law empowered to act as judges in a rabbinical court. All types of Judaism except Orthodox Judaism allow women as well as men to be ordained as rabbis and cantors.[43][44] The leadership of a Jewish congregation is, in fact, in the hands of the laity: the president of a synagogue is its actual leader and any adult male Jew (or adult Jew in non-traditional congregations) can lead prayer services. The rabbi is not an occupation found in the Torah; the first time this word is mentioned is in the Mishnah. The modern form of the rabbi developed in the Talmudic era. Rabbis are given authority to make interpretations of Jewish law and custom. Traditionally, a man obtains one of three levels of Semicha (rabbinic ordination) after the completion of an arduous learning program in Torah, Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Mishnah and Talmud, Midrash, Jewish ethics and lore, the codes of Jewish law and responsa, theology and philosophy.

Since the early medieval era an additional communal role, the Hazzan (cantor) has existed as well. Cantors have sometimes been the only functionaries of a synagogue, empowered to undertake religio-civil functions like witnessing marriages. Cantors do provide leadership of actual services, primarily because of their training and expertise in the music and prayer rituals pertaining to them, rather than because of any spiritual or "sacramental" distinction between them and the laity. Cantors as much as rabbis have been recognized by civil authorities in the United States as clergy for legal purposes, mostly for awarding education degrees and their ability to perform weddings, and certify births and deaths.

Additionally, Jewish authorities license mohalim, people specially trained by experts in Jewish law and usually also by medical professionals to perform the ritual of circumcision.[46] Traditional Orthodox Judaism does not generally license women as mohelot, unless a Jewish male expert is absent, but other movements of Judaism do. They are appropriately called mohelot (pl. of mohelet, f. of mohel).[46] As the j., the Jewish News Weekly of Northern California, states, "...there is no halachic prescription against female mohels, [but] none exist in the Orthodox world, where the preference is that the task be undertaken by a Jewish man".[46] In many places, mohalim are also licensed by civil authorities, as circumcision is technically a surgical procedure. Kohanim, who must avoid contact with dead human body parts (such as the removed foreskin) for ritual purity, cannot act as mohalim,[47] but some mohalim are also either rabbis or cantors.

Another licensed cleric in Judaism is the shochet, who are trained and licensed by religious authorities for kosher slaughter according to ritual law. A Kohen may be a shochet. Most shochetim are ordained rabbis.[48]

Then there is the mashgiach/mashgicha. Mashgichim are observant Jews who supervise the kashrut status of a kosher establishment. The mashgichim must know the Torah laws of kashrut, and how they apply in the environment they are supervising. This can vary. In many instances, the mashgiach/mashgicha is a rabbi. This helps, since rabbinical students learn the laws of kosher as part of their syllabus. However, not all mashgichim are rabbis, and not all rabbis are qualified to be mashgichim.

Orthodox Judaism

[edit]In contemporary Orthodox Judaism, women are usually forbidden from becoming rabbis or cantors.[49] Most Orthodox rabbinical seminaries or yeshivas also require dedication of many years to education, but few require a formal degree from a civil education institution that often define Christian clergy. Training is often focused on Jewish law, and some Orthodox Yeshivas forbid secular education.

In Hasidic Judaism, generally understood as a branch of Orthodox Judaism, there are dynastic spiritual leaders known as Rebbes, often translated in English as "Grand Rabbi". The office of Rebbe is generally a hereditary one, but may also be passed from Rebbe to student or by recognition of a congregation conferring a sort of coronation to their new Rebbe. Although one does not need to be an ordained Rabbi to be a Rebbe, most Rebbes today are ordained Rabbis. Since one does not need to be an ordained rabbi to be a Rebbe, at some points in history there were female Rebbes as well, particularly the Maiden of Ludmir.

Conservative Judaism

[edit]In Conservative Judaism, both men and women are ordained as rabbis and cantors. Conservative Judaism differs with Orthodoxy in that it sees Jewish Law as binding but also as subject to many interpretations, including more liberal interpretations. Academic requirements for becoming a rabbi are rigorous. First earn a bachelor's degree before entering rabbinical school. Studies are mandated in pastoral care and psychology, the historical development of Judaism and most importantly the academic study of Bible, Talmud and rabbinic literature, philosophy and theology, liturgy, Jewish history, and Hebrew literature of all periods.

Reconstructionist and Reform Judaism

[edit]Reconstructionist Judaism and Reform Judaism do not maintain the traditional requirements for study as rooted in Jewish Law and traditionalist text. Both men and women may be rabbis or cantors. The rabbinical seminaries of these movements hold that one must first earn a bachelor's degree before entering the rabbinate. In addition studies are mandated in pastoral care and psychology, the historical development of Judaism; and academic biblical criticism. Emphasis is placed not on Jewish law, but rather on sociology, modern Jewish philosophy, theology and pastoral care.

Sikhism

[edit]Sikh clergy consists of five Jathedars, one each from five takhts or sacred seats. The Jathedars are appointed by the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), an elected body of the Sikhs sometimes called the "Parliament of Sikhs". The highest seat of the Sikh religion is called Akal Takht and the Jathedar of Akal Takht makes all the important decisions after consultations with the Jathedars of the other four takhts and the SGPC.

Zoroastrianism

[edit]Mobad and Magi are the clergy of Zoroastrianism. Kartir was one of the powerful and influential of them.

Traditional religions

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2025) |

Historically traditional (or pagan) religions typically combine religious authority and political power. What this means is that the sacred king or queen is therefore seen to combine both kingship and priesthood within their person, even though he or she is often aided by an actual high priest or priestess (see, for example, the Maya priesthood). When the functions of political ruler and religious leader are combined in this way, deification could be seen to be the next logical stage of their social advancement within their native environment, as is found in the case of the Egyptian Pharaohs. The Vedic priesthood of India is an early instance of a structured body of clergy organized as a separate and hereditary caste, one that occupied the highest social rung of its nation. A modern example of this phenomenon the priestly monarchs of the Yoruba holy city of Ile-Ife in Nigeria, whose reigning Onis have performed ritual ceremonies for centuries for the sustenance of the entire planet and its people.

Health risks for ministry in the United States

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

In recent years, studies have suggested that American clergy in certain Protestant, Evangelical and Jewish traditions are more at risk than the general population of obesity, hypertension and depression.[50][51] Their life expectancies have fallen as of 2010, and their use of antidepressants has risen.[52] Several religious bodies in the United States (Methodist, Episcopal, Baptist and Lutheran) have implemented measures to address the issue, through wellness campaigns, for example—but also by simply ensuring that clergy take more time off.

It is unclear whether similar symptoms affect American Muslim clerics, although an anecdotal comment by one American imam suggested that leaders of mosques may also share these problems.[53]

One exception to the findings of these studies is the case of American Catholic priests, who are required by canon law to take a spiritual retreat each year, and four weeks of vacation.[54] Sociological studies at the University of Chicago have confirmed this exception; the studies also took the results of several earlier studies into consideration and included Roman Catholic priests nationwide.[55] It remains unclear whether American clergy in other religious traditions experience the same symptoms, or whether clergy outside the United States are similarly affected.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Harper, Douglas. "cleric". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29 – via etymonline.com.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "clergy". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29 – via etymonline.com.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "clerk". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29 – via etymonline.com.

- ^ "Cleric". Catholic Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2018-08-20 – via newadvent.org.

- ^ Paul VI, Apostolic letter motu proprio Ministeria quaedam nos. 2–4, 64 AAS 529 (1972).

- ^ Ministeria quaedam no. 1; CIC Canon 266 § 1.

- ^ Nedungatt, George (2002). "Clerics". A Guide to the Eastern Code. CCEO Canon 327. pp. 255, 260.

- ^ Korean Buddhism#Buddhism during Japanese colonial rule

- ^ "Names of Women Ancestors" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-17. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ^ 1Tim 3

- ^ "Code of Canon Law, Canon 207". Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- ^ "Ordinatio Sacerdotalis (May 22, 1994) | John Paul II". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 2024-10-17.

- ^ "Ministeria quaedam - Disciplina circa Primam Tonsuram, Ordines Minores et Subdiaconatus in Ecclesia Latina innovatur, Litterae Apostolicae Motu Proprio datae, Die 15 m. Augusti a. 1972, Paulus PP.VI - Paulus PP. VI". The Holy See. Archived from the original on 2011-11-03. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ a b "Codex Canonum Ecclesiarum orientalium, die XVIII Octobris anno MCMXC - Ioannes Paulus PP. II - Ioannes Paulus II". The Holy See. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ "Code of Canon Law - IntraText". The Holy See. Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ John P. Beal, James A. Coriden, Thomas J. Green, New Commentary on the Code of Canon Law (Paulist Press 2002 ISBN 9780809140664), p. 329

- ^ "Code of Canon Law - IntraText". The Holy See. Archived from the original on 2011-05-08. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ "Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches, canons 342-356". Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ W. Braumüller, W. (2006). The Rusyn-Ukrainians of Czechoslovakia: An Historical Survey. University of Michigan Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-3-7003-0312-1.

- ^ Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers CCEL.org Archived 2005-07-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Clergy Etiquette Archived 2009-11-22 at the Wayback Machine", Orthodox Christian Information Center.

- ^ "Forms of Addresses and Salutations for Orthodox Clergy". Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. Archived from the original on Feb 6, 2017.

- ^ Ken Parry, David Melling, Dimitri Brady, Sidney Griffith & John Healey (eds.), 1999, The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity, Oxford, pp116-7

- ^ "Candidacy Towards Ordination | SCC, United Methodist Church" (PDF).

- ^ "Questions and Answers - ensign". ChurchofJesusChrist.org. Archived from the original on 2020-02-19. Retrieved 2019-07-15.

- ^ "General Authorities," Archived 2014-11-11 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopedia of Mormonism, p. 539

- ^ The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, "Why Don't Mormons Have Paid Clergy?" Archived 2014-05-08 at the Wayback Machine, mormon.org.

- ^ "The Augsburg Confession". www.gutenberg.org. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ^ "Power and Primacy of the Pope (1537): Smalcald Theologians". www.projectwittenberg.org. Archived from the original on 2022-02-07. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ^ Confident.Faith (2019-12-10). "Art. XIV: Of Ecclesiastical Order | Book of Concord". thebookofconcord.org. Retrieved 2024-10-17.

- ^ Presbyterian Church (USA). Book of Order: 2009-2011 (Louisville: Office of the General Assembly), Form of Government, Chapter 6 and 14. See also "Theology and Worship" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-03-07.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (2018-09-23). "Arcaka: 11 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. Archived from the original on 2022-09-28. Retrieved 2022-09-28.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (2014-08-03). "Purohita: 24 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. Archived from the original on 2022-09-20. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- ^ "Swamins and Brahmacharins". Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ Dubois, Jean Antoine; Beauchamp, Henry King (1897). Hindu Manners, Customs and Ceremonies. Clarendon Press. p. 15. Archived from the original on 2023-12-24. Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ Gandhi, Dr Srinivasan (2018-09-05). Hinduism And Brotherhood. Notion Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-64324-834-9. Archived from the original on 2023-12-24. Retrieved 2023-12-24.

- ^ "Hindu Religious Worker Definitions". Hindu American Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Pipes, Daniel (1983). In the Path of God: Islam and Political Power. Routledge. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-351-51291-6. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ^ Brown, Jonathan A.C. (2014). Misquoting Muhammad: The Challenge and Choices of Interpreting the Prophet's Legacy. Oneworld Publications. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-78074-420-9. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ "Qurbani Meat Distribution Rules". Muslim Aid. Archived from the original on 2022-08-22. Retrieved 2022-08-22.

- ^ The Muslim Resurgence in Ghana Since 1950: Nathan Samwini - 2003 p151

- ^ Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jamaʻat: History, Belief, Practice, p.93, Simon Ross Valentine, 2008.

- ^ "Orthodox Women To Be Trained As Clergy, If Not Yet as Rabbis". Forward.com. 21 May 2009. Archived from the original on 6 December 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ "The Cantor". myjewishlearning.com. My Jewish Learning. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2013.

- ^ Klapheck, Elisa. "Regina Jonas". The Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women. Jewish Women's Archive. Archived from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2021 – via jwa.org.

- ^ a b c "Making the cut". j., the Jewish News Weekly of Northern California. 3 March 2006. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2013 – via jweekly.com.

- ^ Citron, Aryeh. "The Kohen's Purity".

- ^ Grandin, Temple (1980). "Problems With Kosher Slaughter". International Journal for the Study of Animal Problems. 1 (6): 375–390. Archived from the original on 2017-01-18. Retrieved 2017-01-17 – via The Humane Society of the United States.

- ^ Schachter, Hershel (2011). "Women Rabbis?" (PDF). Hakirah.

- ^ Eagle, David; Holleman, Anna; Olvera, Brianda Barrera; Blackwood, Elizabeth (July 2024). "Prevalence of obesity in religious clergy in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Obesity Reviews. 25 (7) e13741. doi:10.1111/obr.13741. ISSN 1467-789X. PMID 38572610.

- ^ Eagle, David; Holleman, Anna; Olvera, Brianda Barrera; Blackwood, Elizabeth (July 2024). "Prevalence of obesity in religious clergy in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Obesity Reviews. 25 (7). doi:10.1111/obr.13741. ISSN 1467-7881.

- ^ Vitello, Paul (August 1, 2010). "Taking a Break From the Lord's Work". The New York Times.

- ^ Vitello, Paul (2 August 2010). "Evidence Grows of Problem of Clergy Burnout". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ "CanonLaw.Ninja - Search Results". CanonLaw.Ninja. Retrieved 2024-10-17.

- ^ See A. M. Greeley, Priests: A Calling in Crisis (University of Chicago Press, 2004).

Further reading

[edit]Clergy in general

[edit]- Aston, Nigel. Religion and revolution in France, 1780–1804 (CUA Press, 2000)

- Bremer, Francis J. Shaping New Englands: Puritan Clergymen in Seventeenth-Century England and New England (Twayne, 1994)

- Dutt, Sukumar. Buddhist monks and monasteries of India (London: G. Allen and Unwin, 1962)

- Farriss, Nancy Marguerite. Crown and clergy in colonial Mexico, 1759–1821: The crisis of ecclesiastical privilege (Burns & Oates, 1968)

- Ferguson, Everett. The Early Church at Work and Worship: Volume 1: Ministry, Ordination, Covenant, and Canon (Casemate Publishers, 2014)

- Freeze, Gregory L. The Parish Clergy in Nineteenth-Century Russia: Crisis, Reform, Counter-Reform (Princeton University Press, 1983)

- Haig, Alan. The Victorian Clergy (Routledge, 1984), in England

- Holifield, E. Brooks. God's ambassadors: a history of the Christian clergy in America (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2007), a standard scholarly history

- Lewis, Bonnie Sue. Creating Christian Indians: Native Clergy in the Presbyterian Church (University of Oklahoma Press, 2003)

- Marshall, Peter. The Catholic Priesthood and the English Reformation (Clarendon Press, 1994)

- Osborne, Kenan B. Priesthood: A history of ordained ministry in the Roman Catholic Church (Paulist Press, 1989), a standard scholarly history

- Parry, Ken, ed. The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity (John Wiley & Sons, 2010)

- Sanneh, Lamin. "The origins of clericalism in West African Islam". The Journal of African History 17.01 (1976): 49–72.

- Schwarzfuchs, Simon. A concise history of the rabbinate (Blackwell, 1993), a standard scholarly history

- Zucker, David J. American rabbis: Facts and fiction (Jason Aronson, 1998)

Female clergy

[edit]- Amico, Eleanor B., ed. Reader's Guide to Women's Studies ( Fitzroy Dearborn, 1998), pp 131–33; historiography

- Collier-Thomas, Bettye. Daughters of Thunder: Black Women Preachers and Their Sermons (1997).

- Flowers, Elizabeth H. Into the Pulpit: Southern Baptist Women and Power Since World War II (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2012)

- Maloney, Linda M. "Women in Ministry in the Early Church". New Theology Review 16.2 (2013).

- Ruether, Rosemary Radford. "Should Women Want Women Priests or Women-Church?". Feminist Theology 20.1 (2011): 63–72.

- Tucker, Ruth A. and Walter L. Liefeld. Daughters of the Church: Women and Ministry from New Testament Times to the Present (1987), historical survey of female Christian clergy

External links

[edit]- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Church Administration" – The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

- Wlsessays.net, Scholarly articles on Christian Clergy from the Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary Library

- University of the West, Buddhist M.Div.

- Naropa University Archived 2007-02-08 at the Wayback Machine, Buddhist M.Div.

- National Association of Christian Ministers, Priesthood of All Believers: Explained and Supported in Scripture

Clergy

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Terminology

Etymology

The term "clergy" originates from the Late Latin clericus, meaning "clerk" or "one in holy orders," which itself derives from the Greek klērikos ("clerical" or "pertaining to the clergy"), rooted in klēros ("lot" or "heritage").[4][6] This Greek term references the biblical concept of inheritance, particularly the Levites' allotment as a priestly heritage in the Old Testament, as translated in the Septuagint and echoed in New Testament passages like 1 Peter 5:3, where clergy are described as God's "heritage."[6][7] In early medieval Europe, following the fall of the Roman Empire, the word entered Old English as clerc or cleric, initially denoting literate individuals serving the church, as literacy was largely confined to ecclesiastical circles.[8] By the Middle English period around the 13th century, it had evolved through Old French clergie ("learned men" or "office of a clergyman") to encompass the collective body of ordained religious leaders, shifting from a broader association with scholarly or scribal roles to a specific religious vocation.[4][9] This semantic broadening reflected the institutionalization of the church, where clericus distinguished ordained ministers from the unordained laity.[7] Related terms include "cleric" (directly from Late Latin clericus, referring to an individual church official) and "clergyman" (emerging in the 16th century to specify a male member of the clergy).[10][11] Non-English equivalents preserve similar roots, such as French clergé (from Old French clergie) and German Klerus (adapted from Latin clericus), both denoting the ordained class in Christian contexts.[4][9]Definitions and Distinctions

The clergy consists of ordained or consecrated individuals within a religious tradition who are authorized to perform sacred rites, lead worship, administer sacraments or rituals, and provide spiritual guidance to adherents.[12] This designation emphasizes a formal commissioning or holy orders that sets them apart for ministerial roles, distinguishing them from other participants in religious life.[13] A fundamental distinction exists between clergy and laity, with clergy representing the ordained class empowered to conduct official religious functions, while laity encompasses unordained congregants who engage in communal worship and faith practices but lack sacramental authority.[14] Similarly, clergy differ from other religious specialists, such as monks or nuns, who may take vows of religious life and contribute to spiritual communities but do not necessarily receive ordination to officiate rites unless additionally consecrated.[15] Variations in the concept of clergy arise across traditions, reflecting differing structures of authority and ritual performance. In Christianity, the term encompasses a hierarchy including bishops, priests, and deacons, all ordained through apostolic succession to represent Christ in liturgical acts.[16] In Judaism, rabbis function as clergy equivalents, serving as scholars, teachers of Torah, and officiants at life-cycle events, though without the hereditary priesthood of ancient times.[17] In Islam, no centralized ordained clergy exists; imams act as community leaders who lead prayers, deliver sermons, and offer counsel based on knowledge of Islamic texts, selected by congregations rather than through formal consecration.[18] Some Christian denominations also recognize elders or deacons as partial or auxiliary clergy with limited ministerial roles.[13] In secular legal contexts, definitions of clergy often focus on recognition for fiscal benefits, such as tax exemptions. In the United States, the Internal Revenue Service considers clergy to include duly ordained, commissioned, or licensed ministers who perform ministerial services, exempting their housing allowances from federal income taxation to support religious duties.[19] In the United Kingdom, legislation provides council tax exemptions for properties occupied by ministers of religion when used as residences for fulfilling ecclesiastical offices.[20]Roles and Functions

Spiritual and Sacramental Duties

Clergy fulfill essential spiritual and sacramental duties by serving as conduits between the divine and human communities, facilitating rituals that foster spiritual connection and communal devotion. These responsibilities typically require formal ordination, which empowers individuals to perform sacred functions within their traditions.[21] A core duty involves leading worship services, prayers, and rituals, which vary by tradition but universally aim to invoke divine presence and guidance. In Christianity, priests preside over the Eucharist, a ritual meal symbolizing Christ's body and blood, during which they consecrate bread and wine to nourish the faithful spiritually.[22] Similarly, in Hinduism, priests conduct puja, a devotional worship involving offerings of flowers, incense, and food to deities, often accompanied by mantras and chants to honor the divine and seek blessings for participants.[23] In Islam, imams lead congregational prayers (salah), particularly the Friday Jumu'ah service, reciting the Quran and guiding worshippers in synchronized prostrations to affirm submission to Allah.[24] Jewish rabbis lead synagogue services, including the recitation of prayers from the Siddur and the Torah reading, creating a space for communal reflection on sacred texts.[25] Buddhist monks perform chanting ceremonies and rituals, such as reciting sutras during vesak festivals, to invoke the Buddha's teachings and promote mindfulness among the assembly.[26] Administering sacraments or rites of passage forms another pivotal responsibility, marking life's transitions with sacred significance. Christian clergy officiate baptisms to initiate believers into the faith, marriages to sanctify unions, funerals to commend souls to God, and confession to offer absolution for sins.[22] In Judaism, rabbis conduct brit milah (circumcision) for newborns, bar/bat mitzvah ceremonies for adolescents, and wedding rituals under the chuppah, embedding these events in halakhic tradition.[25] Hindu priests oversee samskaras, including name-giving ceremonies, weddings with fire rituals (saptapadi), and last rites (antyeshti) involving cremation and ancestral offerings.[23] Islamic imams lead nikah marriage contracts, aqiqah naming rites for infants, and janazah funeral prayers to ensure proper Islamic burial.[24] In Buddhism, monks perform ordinations, offer blessings at weddings with merit-making chants, and perform funeral rites, such as chants during cremation ceremonies and merit transfer, to aid the deceased's rebirth.[26] Preaching and teaching doctrine, along with interpreting scriptures, enable clergy to impart moral and spiritual guidance. Rabbis deliver drashot (sermons) expounding Torah portions, clarifying ethical imperatives for daily life.[25] Imams provide khutbah sermons during prayers, drawing from the Quran and Hadith to address contemporary issues through Islamic principles.[24] Hindu priests explain Puranic stories and Vedic hymns during rituals, fostering understanding of dharma (cosmic order).[23] Christian priests offer homilies based on biblical readings, applying teachings to foster faith and virtue.[22] Buddhist monks teach dhamma talks on the Eightfold Path, guiding adherents toward enlightenment.[26] As intermediaries between the divine and human realms, clergy perform blessings, exorcisms, and other acts to mediate spiritual forces. In Christianity, priests bestow blessings and conduct exorcisms to expel evil influences, invoking God's protection.[22] Islamic imams recite protective dua (supplications) and ruqyah for healing or warding off jinn.[24] Hindu priests offer ashirvada (blessings) during pujas and perform shanti rituals to appease malevolent spirits.[23] Rabbis pronounce berakhot (blessings) at lifecycle events, channeling divine favor.[25] Monks in Buddhism lead paritta chanting to generate protective merit against harm.[26] Clergy also engage in pastoral counseling for spiritual crises, offering compassionate guidance rooted in doctrine. This includes addressing doubt, grief, or ethical dilemmas through scripture-based dialogue.[24] Additionally, they maintain sacred spaces, such as preparing altars for rituals—arranging icons in Christian churches, Torah arks in synagogues, mihrabs in mosques, or deity images in Hindu temples and Buddhist shrines—to ensure environments conducive to worship.[21]Pastoral and Administrative Responsibilities

Clergy play a vital role in fostering community cohesion through the organization of events, charity initiatives, and social outreach programs that extend the reach of their religious institutions beyond formal worship. These activities often include coordinating volunteer efforts to address local needs, such as food drives or educational workshops, which strengthen bonds among congregants and attract new participants. For instance, many clergy oversee youth groups to provide structured activities that promote social development and mentorship among younger members.[27][28][29] In times of crisis, clergy frequently lead disaster relief efforts, mobilizing resources and personnel to offer immediate aid like shelter and emotional support to affected communities. Faith-based organizations, under clerical guidance, have been instrumental in long-term recovery, providing supplies and coordinating with secular agencies to rebuild infrastructure and support vulnerable populations. This outreach not only addresses practical needs but also builds trust and resilience within diverse neighborhoods.[30][31] Beyond community events, clergy offer counseling for personal challenges such as grief, marital conflicts, and addiction, emphasizing emotional and practical guidance integrated with spiritual and doctrinal insights to help individuals navigate life's difficulties. This support focuses on empathetic listening and resource referral, drawing on interpersonal skills to foster healing. Such sessions often occur in private settings, allowing clergy to act as accessible confidants for congregants facing everyday stressors.[32][33] Administrative duties form a core component of clerical work, encompassing the management of institutional finances, property maintenance, and volunteer coordination to ensure smooth operations. Clergy typically serve as the primary administrative officers, handling budgeting, payroll, and compliance with legal requirements while delegating tasks to lay leaders. This oversight includes organizing schedules for facility use and maintaining records, which sustains the physical and fiscal health of religious centers.[34][27][35] Clergy also engage in advocacy, representing their faith traditions in interfaith dialogues to promote mutual understanding and collaborative initiatives on shared concerns. These interactions often involve joint events or discussions that bridge religious divides, enhancing social harmony. Additionally, clergy advocate on public policy matters related to ethical issues, such as social justice or environmental stewardship, by testifying before lawmakers or issuing statements that align with moral teachings.[36][37][38]Education and Ordination

Theological Education

Theological education forms the foundational preparation for individuals aspiring to serve as clergy, encompassing formal academic study, spiritual formation, and practical training tailored to specific religious traditions. This preparation equips candidates with the knowledge and skills necessary to interpret sacred texts, lead worship, provide pastoral care, and engage in ethical leadership within their communities. Across faiths, programs typically emphasize a blend of intellectual rigor and personal spiritual development, often culminating in ordination, though the educational pathways vary significantly by tradition. Common paths to clerical roles include enrollment in seminaries, divinity schools, rabbinical seminaries, or yeshivas, with programs generally lasting 3 to 7 years depending on the denomination and region. For instance, in Christianity, candidates often pursue a Master of Divinity (MDiv) degree, a standard three-year graduate program that builds on a prior bachelor's degree. Prerequisites typically include a bachelor's degree in any field, along with recommendations from religious leaders and sometimes psychological evaluations to assess suitability for ministry. Spiritual formation is integrated throughout, involving mentorship, retreats, and reflective practices to foster personal growth alongside academics. In Judaism, rabbinical training at institutions like yeshivas or Hebrew Union College involves intensive study over 4 to 6 years, focusing on Talmudic analysis and halakhic decision-making, with a bachelor's degree as a common entry requirement. The curriculum in theological education universally prioritizes the study of scriptures, theology, and ethics, supplemented by practical disciplines such as homiletics (the art of preaching) and pastoral counseling. Language training is a key component, including ancient tongues like Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic for accessing primary texts in Abrahamic faiths; for example, Christian seminaries often require proficiency in biblical Greek and Hebrew to engage with the New Testament and Old Testament originals. In Islamic madrasas, curricula emphasize Quranic exegesis (tafsir), hadith studies, and fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), with Arabic language immersion essential for textual analysis. Hindu pandit training, often through gurukuls or Vedic schools, centers on memorization and recitation of Sanskrit scriptures like the Vedas and Upanishads, alongside rituals and philosophy, which can span several years to over a decade under a guru's guidance, varying by tradition and program. Ethical training addresses contemporary issues such as social justice and interfaith dialogue, ensuring clergy are prepared for diverse societal contexts. Institutions providing theological education range from denominational seminaries to interfaith divinity schools, reflecting the global diversity of clerical preparation. In Christianity, prominent examples include Princeton Theological Seminary and Fuller Theological Seminary, which offer MDiv programs accredited by the Association of Theological Schools, emphasizing both evangelical and mainline Protestant perspectives. Islamic madrasas, such as Al-Azhar University in Egypt, provide comprehensive training for imams through a blend of traditional and modern curricula, often culminating in advanced degrees in Islamic studies. In Hinduism, traditional paths like those at the Sringeri Sharada Peetham involve apprenticeship-style learning in Vedic recitation and temple rituals, contrasting with more formalized programs at institutions like the Sanskriti University. Prerequisites for entry often include demonstrated religious commitment, such as prior volunteer service in a faith community, alongside academic qualifications. Global variations in theological education highlight adaptations to cultural and institutional contexts, with some traditions favoring shorter apprenticeships over extended academic degrees. In certain evangelical Christian circles, accelerated programs or Bible colleges offer 2- to 4-year certifications focused on practical ministry skills, bypassing the full MDiv for faster entry into service. Orthodox Jewish training in hasidic communities may emphasize yeshiva immersion from a young age, with less formal degree structures. In Islam, rural madrasas in South Asia might prioritize oral transmission and community apprenticeship, lasting 3-5 years, while urban programs align with university standards. Hindu training in diaspora communities, such as those in the United States through organizations like the Hindu Students Council, increasingly incorporates bachelor's-level prerequisites and hybrid online elements to accommodate working adults. As of 2025, many programs worldwide have increasingly incorporated online and hybrid formats, as well as competency-based models, to address accessibility and enrollment challenges.[39] These differences underscore a spectrum from rigorous, degree-oriented paths to mentorship-based models, all aimed at producing clergy attuned to their religious and societal roles.Ordination Processes and Authority

Ordination represents the formal rite through which individuals are invested with clerical authority, often involving symbolic acts such as the laying on of hands, recitation of vows, or initiation ceremonies that signify a sacred commissioning.[40] In many traditions, this process confers spiritual powers, such as the ability to administer sacraments or lead worship, marking a transition from lay to ordained status.[41] The sources of clerical authority vary across religious systems but commonly derive from scripture, ecclesiastical tradition, or communal election. In scriptural models, authority is rooted in divine mandates, such as biblical passages appointing leaders like apostles or prophets.[42] Traditions emphasize continuity through apostolic succession or inherited lineages, where authority is passed via ordained superiors.[43] Congregational models, prevalent in some Protestant contexts, involve community affirmation, such as elections or votes by members to recognize leaders like elders.[44] Hierarchical systems often delineate multiple levels of clergy, each with distinct roles and rites of ordination. For instance, in Catholic and Orthodox Christianity, deacons receive ordination for service roles, priests for sacramental ministry like Eucharist celebration, and bishops for oversight and consecration of others, all through the sacrament of Holy Orders involving episcopal imposition of hands.[40] In contrast, Protestant traditions like Presbyterianism ordain elders—teaching and ruling—for local governance without a strict hierarchy, focusing on shared ministry.[45] Revocation of clerical status, known as defrocking or laicization, occurs through formal ecclesiastical processes for reasons such as doctrinal heresy, moral misconduct, or criminal acts, stripping the individual of official duties while the indelible character of ordination remains in some views.[46] These procedures typically involve investigation, trial by church authorities, and pronouncement, ensuring accountability without undermining the rite's sacramental nature.[47] Cross-traditionally, ordination manifests differently: in Judaism, semicha grants rabbinic authority through examination and certification by scholars, distinct from rites of passage like bar mitzvah that confer adult religious responsibilities without leadership powers.[48] Islam lacks a formal ordination for imams, who derive authority from knowledge and community selection rather than ritual investiture.[49] In Buddhism, upasampada ordination integrates novices into the sangha via vows before a monastic assembly, emphasizing ethical commitment over hierarchical power.[50] Hinduism's priestly roles often stem from varna inheritance or guru-disciple initiation, without universal ordination ceremonies.[51]History

Ancient and Classical Periods

In ancient civilizations, the rise of urbanization around 3000 BCE marked a pivotal shift from shamanistic practices, where individual spiritual intermediaries communed directly with the divine through ecstatic or personal rituals, to more institutionalized forms of religious authority centered in temples and managed by specialized clergy. This transition was driven by the needs of growing urban populations for structured mediation between humans and gods, economic administration of temple resources, and the legitimization of emerging state powers through sacred rituals. In early cities like those in Mesopotamia and Egypt, priests assumed roles as custodians of cosmic order, interpreters of divine will, and overseers of communal welfare, laying the foundation for hereditary and professional clerical classes that persisted across cultures.[52][53] In Mesopotamia, temple-based priesthoods emerged by approximately 3000 BCE as central to religious and social life, with priests serving as intermediaries who conducted daily rituals to appease deities, maintained temple estates that functioned as economic hubs, and interpreted omens and oracles to guide kings and communities. These priests, often organized into hierarchical colleges such as the ēnu (high priests) and sangû (ritual specialists), performed sacrifices, divination through liver inspections (extispicy), and festivals that reinforced urban cohesion and agricultural cycles. Temples like the Eanna in Uruk exemplified this system, where clergy not only handled sacred duties but also managed vast landholdings and labor forces, blending spiritual and administrative authority.[54][55] Similarly, in ancient Egypt from around 3000 BCE, priests operated within temple complexes as the primary officiants of rituals in the king's stead, ensuring the gods' favor through offerings, processions, and oracular consultations that influenced royal decisions and public life. High priests, such as the hem-netjer (servant of the god), oversaw elaborate ceremonies in sanctuaries like Karnak, while lower ranks handled purification rites, animal sacrifices, and the maintenance of divine statues believed to embody the gods. Oracles, particularly those of Amun at Thebes, involved priests interpreting divine responses via yes/no movements of barque shrines during festivals, providing guidance on matters from personal disputes to state affairs and underscoring the clergy's role in upholding ma'at (cosmic harmony). Hereditary succession within priestly families became common by the Middle Kingdom, solidifying their institutional power.[56][57][58] In ancient India, during the Vedic period around 1500 BCE, Brahmin priests emerged as the ritual experts who composed and recited hymns from the Rigveda, performing yajna (sacrificial ceremonies) to invoke deities like Indra and Agni for prosperity and cosmic balance. These priests, drawn from the highest social stratum, held specialized knowledge of sacred chants and formulas, acting as conduits between humans and the divine while advising chieftains on warfare and fertility rites. Figures like Vasishtha and Vishvamitra exemplified their influence, with Brahmins overseeing fire altars and soma rituals that structured early Indo-Aryan society, transitioning from nomadic shaman-like roles to a formalized priesthood tied to emerging settlements.[59][60] Ancient Judaism developed a hereditary clerical system centered on the Levites and kohanim (priests), as outlined in the Torah, where the tribe of Levi—descended from Aaron—was designated for temple service, with kohanim performing sacrifices and blessings exclusively. The Levites assisted in tabernacle maintenance, music, and teaching the law, while kohanim handled atonement rites and oracular inquiries via the Urim and Thummim, ensuring ritual purity and communal adherence to divine covenants. Following the Babylonian Exile (c. 586–539 BCE), post-exilic developments under Persian rule emphasized the priesthood's restoration, with figures like Joshua the High Priest rebuilding the Second Temple in 516 BCE and kohanim gaining prominence in agrarian and judicial roles, adapting hereditary duties to a diaspora-influenced Judaism focused on scriptural interpretation and local synagogues.[61][62][63] In the Greco-Roman world, religious officials like augurs and flamens institutionalized divination and state cults from the Republic onward, with augurs interpreting bird flights and lightning (auspicia) to discern divine approval for public actions, forming a college that advised magistrates on policy and warfare. Flamens, as high priests dedicated to specific gods like Jupiter or Vesta, conducted exclusive rituals, maintained temple purity, and participated in festivals, their roles often hereditary within patrician families to preserve ritual efficacy. By the 1st–4th centuries CE, early Christian communities adapted these structures, evolving bishops (episkopoi) from overseers of local house churches into authoritative figures by the late 1st century, as seen in cities like Jerusalem and Ephesus, where they led Eucharist, resolved disputes, and combated heresies, culminating in the episcopal hierarchy formalized at councils like Nicaea in 325 CE.[64][65][66]Medieval and Modern Developments