Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Austrian Partition

View on Wikipedia| The Austrian Partition | |

|---|---|

| The Commonwealth | |

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772 | |

| Elimination | |

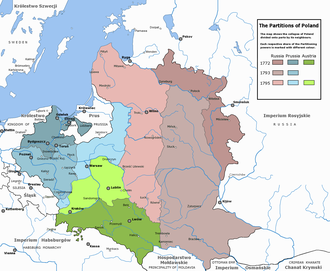

The three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Russian Partition (pink and brown), the Austrian Partition (green), and the Prussian Partition (blue) |

The Austrian Partition (Polish: zabór austriacki) comprises the former territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth acquired by the Habsburg monarchy during the Partitions of Poland in the late 18th century. The three partitions were conducted jointly by the Russian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia and Habsburg Austria, resulting in the complete elimination of the Polish Crown. Austria acquired Polish lands during the First Partition of 1772, and Third Partition of Poland in 1795.[1] In the end, the Austrian sector encompassed the second-largest share of the Commonwealth's population after Russia;[note 1] over 2.65 million people living on 128,900 km2 (49,800 sq mi) of land constituting the formerly south-central part of the Republic.[3]

History

[edit]The territories acquired by Austrian Empire (later the Austro-Hungarian Empire) during the First Partition included the Polish Duchy of Zator and Duchy of Oświęcim, as well as part of Lesser Poland with the counties of Kraków, Sandomierz and Galicia, less the city of Kraków. In the Third Partition, the annexed lands included so called "Western Galicia": northern Lesser Poland (voivodeships of Lublin and Sandomierz) and southern Masovia. Major historical events of the Austrian Partition included: the formation of the Napoleonic Duchy of Warsaw in 1807, which was followed by the 1809 Austro-Polish War aided by the French, and the victorious Battle of Raszyn resulting in Austrian temporary defeat (1809) marked by the recapture of Kraków and Lwów by the Duchy. However, the fall of Napoleon, leading to abolition of the Duchy at the Congress of Vienna (1815) allowed Austria to regain control. The Congress created the Free City of Kraków protectorate of Austria, Prussia and Russia, which lasted for a decade. It was abolished by Austria, after the crushing of Kraków Uprising in 1846. The formation of the Polish Legions by Piłsudski initially to fight alongside the Austro-Hungarian Army,[4] helped Poland regain its sovereignty in aftermath of World War I.

Society

[edit]

For most of the 19th century, the Austrian government made few or no concessions to their Polish constituents,[5] their attitude being that a "patriot was a traitor – unless he was a patriot for the [Austrian] Emperor."[6] However, by the early 20th century – just before the outbreak of World War I and the collapse of Austria-Hungary – out of the three partitions, the Austrian one had the most local autonomy.[7] The local government called the Governorate Commission (Polish: Komisja Gubernialna) had considerable influence locally, Polish was accepted as the official regional language on Polish soil, and used in schools; Polish organizations had some freedom to operate, and Polish parties could formally participate in Austro-Hungarian politics of the empire.[7]

Austria-Hungary also de facto encouraged (the flourishing[8]) Ukrainian organizations as a "divide and rule" tactic.[9][10] This led to accusations by Poles that "Austria-Hungary had invented Ukrainians".[10] Ukrainians maintained schools (from elementary to higher levels)[note 2] and newspapers[note 3] in the Ukrainian language.[8][12] After 1848 Ukrainians also moved into Austrian politics with their own political parties.[8] Austria-Hungary gave Ukrainians more rights than Ukrainians living in the Russian Empire.[13] Decades after it had ceased to exist its former Ukrainian citizens had positive emotions about Austria-Hungary.[13]

Economy

[edit]On the other hand, economically, Galicia was rather backward, and universally regarded as the poorest of the three partitions.[7] There was much corruption during the elections, and the region was seen by the Viennese government as the low priority for investment and development.[7] It was a vast, but constantly struggling region with inefficient agriculture and little industry. In 1900, 60% of the village population (age 12 and over) could not read or write.[7] Education was obligatory until the age of 12, but this requirement was often ignored.[7] Between the years 1850 and 1914 it is estimated that about 1 million people from Galicia (mostly Poles) emigrated to United States.[7] "Galician poverty" and "Galician misery" to this day have survived in Polish as expressions of hopelessness (adage: bieda galicyjska or nędza galicyjska).[7][14]

Administrative division

[edit]The Austrian Empire divided the former territories of the Commonwealth it obtained into:

- Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria – from 1772 to 1918.

- West Galicia – from 1795 to 1809

- Free City of Kraków – from 1815 to 1846

Two important and major cities of the Austrian partition were Kraków (German: Krakau) and Lwów (German: Lemberg).

In the first partition, Austria received the largest share of the formerly Polish population, and the second largest land share (83,000 square kilometres (32,000 sq mi) and over 2.65 million people). Austria did not participate in the second partition, and in the third, it received 47,000 square kilometres (18,000 sq mi) with 1.2 million people. Overall, Austria gained about 18 percent of the former Commonwealth territory (130,000 square kilometres (50,000 sq mi)) and about 32 percent of the population (3.85 million people).[15] From the geographical perspective, much of the Austrian partition corresponded to the Galicia region.

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ The "Austrian sector" is a historical term used by scholars in reference to Commonwealth territories consisting of Polish heritage dating as far back as the first days of Poland's statehood.[2]

- ^ This Ukrainian education system was also in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[9]

- ^ The first published in 1848.[10][11]

References

[edit]- ^ Norman Davies (2005), "Galicia: The Austrian Partition", God's Playground A History of Poland, vol. II: 1795 to the Present, Oxford University Press, pp. 102–119, ISBN 0199253404, retrieved November 24, 2012

- ^ William Fiddian Reddaway, ed. (1941). "Galicia in the Period of Autonomy and Self-Government, 1849–1914". The Cambridge History of Poland. Vol. 2. CUP Archive. pp. 434–. ISBN 9287148821. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Norman Davies (2005). "Austrian Partition". God's Playground. A History of Poland. The Origins to 1795. Vol. I (Revised ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 367, 393. ISBN 0199253390.

- ^ Hein Erich Goemans, War and Punishment: The Causes of War Termination and the First World War, Princeton University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-691-04944-0, pp. 104-5

- ^ Jerzy Lukowski, Hubert Zawadzki, A Concise History of Poland, Cambridge University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-521-55917-0, p. 129

- ^ Anatol Murad (1968). "Chapter 3: Franz Joseph's Lands and Peoples". Franz Joseph I of Austria and His Empire (First printing ed.). New York: Twayn Publishers. p. 17. Retrieved December 1, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Andrzej Garlicki, Polsko-Gruziński sojusz wojskowy, Polityka: Wydanie Specjalne 2/2008, ISSN 1730-0525, p. 11-12

- ^ a b c Ukrainian Security Policy by Taras Kuzio, 1995, Praeger, ISBN 0275953858 (page 9)

- ^ a b Serhy Yekelchyk Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation, Oxford University Press (2007), ISBN 978-0-19-530546-3

- ^ a b c Ukraine: A History, 4th Edition by Orest Subtelny, 2009, Toronto, Canada, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-1-4426-4016-0 & ISBN 978-1-4426-0991-4

- ^ Jeremy Popkin, ed., Media and Revolution: Comparative Perspectives (University of Kentucky Press, 1995)

- ^ Mark von Hagen. (2007). War in a European Borderland. University of Washington Press. pg. 4

- ^ a b History of Ukraine – The Land and Its Peoples by Paul Robert Magocsi, University of Toronto Press, 2010, ISBN 1442640855 (page 482)

- ^ David Crowley, National Style and Nation-state: Design in Poland from the Vernacular Revival to the International Style, Manchester University Press ND, 1992 ISBN 0-7190-3727-1, p. 12

- ^ Piotr Stefan Wandycz, The Price of Freedom: A History of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the Present, Routledge (UK), 2001, ISBN 0-415-25491-4, p. 133.

Further reading

[edit]- Norman Davies: God's Playground, pp. 102-119: "GALICIA: The Austrian Partition (1773–1918)"