Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Prussian Partition

View on Wikipedia| The Prussian Partition | |

|---|---|

| The Commonwealth | |

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772 | |

| Elimination | |

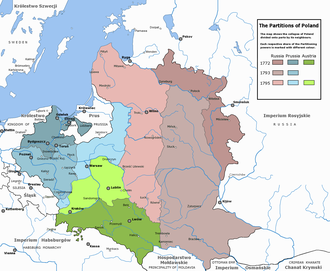

The three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Russian Partition (red), the Austrian Partition (green), and the Prussian Partition (blue) |

The Prussian Partition (Polish: Zabór pruski), or Prussian Poland, is the former territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth acquired during the Partitions of Poland, in the late 18th century by the Kingdom of Prussia.[1] The Prussian acquisition amounted to 141,400 km2 (54,600 sq mi) of land constituting formerly western territory of the Commonwealth. The first partitioning led by imperial Russia with Prussian participation took place in 1772; the second in 1793, and the third in 1795, resulting in Poland's elimination as a state for the next 123 years.[2]

History

[edit]The Kingdom of Prussia acquired Polish territories in all three military partitions.[2]

The First Partition

[edit]The First Partition of Poland in 1772 included the annexation of the formerly Polish Prussia by Frederick II who quickly implanted over 57,000 German families there in order to solidify his new acquisitions.[3] In the first partition, Frederick sought to exploit and develop Poland economically as part of his wider aim of enriching Prussia.[4] and described it as an "artichoke, ready to be consumed leaf by leaf".[5] As early as 1731 Frederick had suggested that his country would benefit from annexing Polish territory.[6] By 1752, he had prepared the ground for the partition of Poland–Lithuania, aiming to achieve his goal of building a territorial bridge between Pomerania, Brandenburg, and his East Prussian provinces.[7] The new territories would also provide an increased tax base, additional populations for the Prussian military, and serve as a surrogate for the other overseas colonies of the other great powers.[8]

Frederick did not justify his conquests on an ethnic basis; he pursued an imperialist policy focused on the security interests of his state.[9] However, Frederick did use propaganda to justify the partition and his economic exploitation of Poland, portraying the acquired provinces as underdeveloped and in need of improvement by Prussian rule; these claims were sometimes accepted by subsequent German historiography and can still be found in modern works.[10] Frederick wrote that Poland had "the worst government in Europe with the exception of Turkey".[11] After a prolonged visit to West Prussia in 1773, Frederick informed Voltaire of his findings and accomplishments: "I have abolished serfdom, reformed the savage laws, opened a canal which joins up all the main rivers; I have rebuilt those villages razed to the ground after the plague in 1709. I have drained the marshes and established a police force where none existed. … [I]t is not reasonable that the country which produced Copernicus should be allowed to moulder in the barbarism that results from tyranny. Those hitherto in power have destroyed the schools, thinking that uneducated people are easily oppressed. These provinces cannot be compared with any European country—the only parallel would be Canada."[12] However, in a letter to his favorite brother, Prince Henry, Frederick admitted that the Polish provinces were economically profitable:

- It is a very good and advantageous acquisition, both from a financial and a political point of view. In order to excite less jealousy I tell everyone that on my travels I have seen just sand, pine trees, heath land and Jews. Despite that there is a lot of work to be done; there is no order, and no planning and the towns are in a lamentable condition.[13]

Frederick's long-term goal was to displace the Poles from the conquered region[14] and colonize it with Germans, whom he considered better workers.[15] To accomplish this goal, Frederick invited thousands of German colonists into the conquered territories by promises of free land.[16] He also engaged in the plunder of Polish property, gradually appropriating starostwie (Polish Crown estates) and monasteries[17] and redistributed them to German landowners.[8] He also aimed to expel the Polish nobles—who were viewed as wasteful, lazy, and negligent[18]—from their land by taxing them at a rate higher than other regions of Prussia,[8] which increased their financial burden and reduced their power.[19] In 1783, Frederick also passed legislation allowed buyouts of noble land.[20] This legislation allowed the free alienation of Polish nobles' estates so that this property could be purchased by German colonists.[21] This resulted in a greater percentage of noble land being transferred to bourgeoise owners than in any other part of Hohenzollern land.[22] Ultimately, Frederick settled 300,000 colonists in territories he had conquered.[8]

Frederick undertook the exploitation of Polish territory under the pretext of an enlightened civilizing mission that emphasized the supposed cultural superiority of Prussian ways.[23] He saw the outlying regions of Prussia as barbaric and uncivilized,[24] He expressed anti-Polish sentiments when describing the inhabitants, such as calling them "slovenly Polish trash".[25] He also compared the Polish peasants unfavorably with the Iroquois,[11] and named three of his new Prussian settlements after colonial areas of North America: Florida, Philadelphia and Saratoga.[16] The Poles remaining in the territories were to be Germanized.[8]

The Polish language was marginalized.[26] Teachers and administrators were encouraged to be able to speak both German and Polish,[27] and recognizing that his kingdom now had Polish inhabitants, Frederick also advised his successors to learn Polish. [27] However, German was to be the language of education.[28] The introduction of compulsory Prussian military service would also Germanize the Poles.[29] And, the rural Poles were to be mixed with German neighbors so these Poles could learn "industriousness", "cleanliness, and orderliness" and acquire a "Prussian character". By such means, Frederick boasted he would "gradually...get rid of all Poles".[30]

The Second Partition

[edit]In the Second Partition of Poland in 1793, the Kingdom of Prussia annexed Gdańsk (Danzig) and Toruń (Thorn), part of the Crown of Poland since 1457. The incursion sparked the first Greater Poland Uprising in Kujawy under Jan Henryk Dąbrowski. The revolt ended after General Tadeusz Kościuszko was captured by the Russians.

The Third Partition

[edit]

The subsequent third partitioning of 1795 marked the Prussian annexation of Podlasie region, with the remainder of Masovia, and the capital city of Warsaw (handed over to the Russians twenty years later by Frederick III).[31]

The second Greater Poland Uprising against Prussian forces (also under General Dąbrowski) broke out in Wielkopolska (Greater Poland) in 1806, ahead of the Prussian total defeat by Napoleon who created the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807. However, the fall of Napoleon during his Russian Campaign lead to the dismantling of the Duchy at the Congress of Vienna (1815) and the return of Prussian control.[2]

The third Greater Poland Uprising under Ludwik Mierosławski occurred in 1846. The Uprising was designed to be part of a general uprising against all three states that had partitioned Poland.[32] Some 254 insurgents were charged with high treason in Berlin. Two years later, during the Spring of Nations, the fourth Polish uprising broke out in and around Poznań in 1848, led by the Polish National Committee. The Prussian army pacified the area and 1,500 Poles were imprisoned in Poznań Citadel. The Uprising showed to Polish insurgents that there was no possibility whatsoever to try to negotiate Polish statehood with the Germans. Only sixty years later, the Greater Poland Uprising (1918–1919) in the Prussian Partition helped Poland regain its freedom in the aftermath of World War I.[26]

Ethnicity

[edit]Apart from ethnic Germans and Poles, the Prussian Partition was also inhabited by ethnolinguistic minorities. Minority groups included Kashubs in West Prussia, Czechs and Moravians in Silesia, Jews, and others.[33]

-

Ethnic structure of the eastern regions of Prussia in 1817–1823

-

Poles in the Kingdom of Prussia during the 19th century:90% – 100% Polish80% – 90% Polish70% – 80% Polish60% – 70% Polish50% – 60% Polish20% – 50% Polish5% – 20% Polish

Society

[edit]

In the late 19th century, non-Germans in the Prussian partition were subject to extensive Germanization policies (Kulturkampf, Hakata).[34] Frederick the Great brought 300,000 colonists to territories he conquered to facilitate Germanization.[35]

That policy, however, had an opposite effect to that which the German leadership had expected: instead of becoming assimilated, the Polish minority in the German Empire became more organized, and its national consciousness grew.[34] Of the Three Partitions, the education system in Prussia was on a higher level than in Austria and Russia, irrespective of its virulent attack on the Polish language specifically, resulting in the Września children strike in 1901–04, leading to persecution and imprisonment for refusing to accept the German textbooks and the German religion lessons.[2][34]

In 1902, after unveiling a statue of Frederick in Posen, Wilhelm offered a speech where he denied German interferences with Polish religion and tradition.[36] He also demanded that the "many races" of Prussia first and foremost hold themselves to be good Prussians. Observers indicated that Wilhelm's speech had little impact on alleviating concerns amongst the populace in the region.[36]

Economy

[edit]From the economic perspective, the territories of the Prussian Partition were the most developed out of the three partitions, thanks to the policies of the government.[34] The German government supported efficient farming, industry, financial institutions and transport.[34]

Administrative division

[edit]In the First Partition, Prussia received 38,000 km² and about 600,000 people.[37] In the second partition, Prussia received 58,000 km² and about 1 million people. In the third, similar to the second, Prussia gained 55,000 km² and 1 million people. Overall, Prussia gained about 20 percent of the former Commonwealth territory (149;000 km²) and about 23 percent of the population (2.6 million people).[38] From the geographical perspective, most of the territories annexed by Prussia formed the province of Greater Poland (Wielkopolska).

The Kingdom of Prussia divided the former territories of the Commonwealth it obtained into the following:

- Netze District - from 1772 to 1793

- New Silesia - from 1795 to 1807

- New East Prussia - from 1795 to 1807

- South Prussia - from 1793 to 1806

- East Prussia - from 1773 to 1829

- West Prussia - from 1773 to 1829

It should also be noted that most of East Prussia, including its capital Königsberg (now Kaliningrad), was already part of the Kingdom of Prussia prior to the partitions of Poland. Upon the first partition of Poland, the Prince-Bishopric of Warmia was annexed by Kingdom of Prussia and added to the province of East Prussia. Over time the administrative divisions changed. Important Prussian administrative areas set up from Polish lands included:

- Grand Duchy of Posen from 1815–1848

- Province of Posen from 1848–1919

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

- ^ Davies 1981, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d Davies 1981.

- ^ Ritter 1936, pp. 179-180..

- ^ Scott 2001, p. 176.

- ^ Clark 2006, p. 231.

- ^ MacDonogh 2000, p. 78.

- ^ Friedrich 2000, p. 189.

- ^ a b c d e Hagen, William W. (1976). "The Partitions of Poland and the Crisis of the Old Regime in Prussia 1772-1806". Central European History. 9 (2): 115–128. doi:10.1017/S0008938900018136. JSTOR 4545765.

- ^ Clark 2006, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Friedrich 2000, p. 12.

- ^ a b Ritter 1936, p. 192.

- ^ Mitford 1984, p. 277.

- ^ MacDonogh 2000, p. 363.

- ^ Finszch, Norbert; Schirmer, Dietmar (2006). Identity and Intolerance: Nationalism, Racism, and Xenophobia in Germany and the United States. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-521-59158-4.

- ^ Ritter 1936, pp. 178-180.

- ^ a b Kakel, Carroll P. (2013). The Holocaust as Colonial Genocide: Hitler's 'Indian Wars' in the 'Wild East'. New York: Springer. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-137-39169-8.

- ^ Konopczyński 1919, pp. 46.

- ^ Clark 2006, p. 227.

- ^ Lerski, Jerzy Jan (1996). Wróbel, Piotr; Kozicki, Richard J. (eds.). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0.

- ^ Brzezina, Maria (1989). Polszczyzna Niemców [The Polish Language of the Germans] (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawn. Nauk. ISBN 978-83-01-09347-1. p. 26:

...ki bylych starostw polskich, dobra pojezuickie i klasztorne, ale już w 1783 r. Fryderyk nakazuje wykupywanie prywatnych majątków polskich.

[[Frederick had previously appropriated] "...former Polish starosties [and] the estates of jesuit institutions and of monasteries, but in 1783 Frederick ordered forced sales of Polish private assets.] - ^ Philippson, Martin (1905). "The First Partition of Poland and the War of the Bavarian Succession". In Wright, John Henry (tr.) (ed.). The Age of Frederick the Great. A History of All Nations from the Earliest Times: Being a Universal Historical Library. Vol. XV. Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co. pp. 227-228.

- ^ Clark 2006, p. 237.

- ^ Clark 2006, p. 239.

- ^ Egremont, Max (2011). Forgotten Land: Journeys among the Ghosts of East Prussia. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-374-53356-4.

- ^ Blackbourn 2006, p. 303.

- ^ a b Andrzej Chwalba, Historia Polski 1795-1918, Wydawnictwo Literackie 2000, Kraków, pages 175-184, and 307-312. ISBN 830804140X.

- ^ a b Koch 1978, p. 136.

- ^ United States Office of Education (1896). Higher Education in Russian, Austrian, and Prussian Poland. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 788.

- ^ Salmonowicz, Stanisław (1993). Polacy i Niemcy wobec siebie: postawy, opinie, stereotypy (1697-1815) : próba zarysu [Poles and Germans in Relation to Each Other: Attitudes, Opinions, Stereotypes (1697-1815): An Attempt at an Outline] (in Polish). Ośrodek Badań Naukowych im. W. Kętrzyńskiego. p. 88:

Służba wojskowa z całą pewnością największym ciężarem dla polskiej ludności, nieckiedy w toku dlugoletniej służby jednostki ulegaly germanizacji

[Military service was by far the greatest burden for the Polish population, and in the course of their long service the units were Germanized]. - ^ Day, David (2008). Conquest: How Societies Overwhelm Others. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-19-923934-4.

- ^ Norman Davies (1996). Europe: a history. Oxford University Press. pp. 828–. ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ Marian Zagórniak, Józef Buszko, Wielka historia Polski vol. 4 Polska w czasach walk o niepodległość (1815–1864). "Od niewoli do niepodległości (1864–1918)", 2003, page 186.

- ^ Belzyt, Leszek (1998). Sprachliche Minderheiten im preussischen Staat: 1815 – 1914; die preußische Sprachenstatistik in Bearbeitung und Kommentar. Marburg: Herder-Inst. ISBN 978-3-87969-267-5.

- ^ a b c d e Andrzej Garlicki, Polsko-Gruziński sojusz wojskowy, Polityka: Wydanie Specjalne 2/2008, ISSN 1730-0525, pp. 11–12

- ^ Jerzy Surdykowski, Duch Rzeczypospolitej, 2001 Wydawn. Nauk. PWN, 2001, page 153.

- ^ a b "KAISER ADDRESSES POLES; Speech at the Provincial Diet House in Posen". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

- ^ Kaplan, Herbert H. (1962). The first partition of Poland. --. New York : Columbia University Press. p. 188. Retrieved 2021-04-21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Piotr Stefan Wandycz, The Price of Freedom: A History of East Central Europe from the Middle Ages to the Present, Routledge (UK), 2001, ISBN 0-415-25491-4, Google Print, p.133

Bibliography

- Blackbourn, David (2006). The Conquest of Nature. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06212-0.

- Clark, Christopher (2006). Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600–1947. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02385-7.

- Davies, Norman (1981). "PREUSSEN: The Prussian Partition (1772–1918)". God's Playground: A History of Poland. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 112–138.

- Friedrich, Karin (2000). The Other Prussia: Royal Prussia, Poland and Liberty, 1569–1772. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58335-0.

- Koch, H. W. (1978). A History of Prussia. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. ISBN 978-0-88029-158-3.

- Konopczyński, Władysław (1919). A Brief Outline of Polish History. Translated by Benett, Francis. Geneva: Imprimierie Atar.

- MacDonogh, Giles (2000). Frederick the Great: A Life in Deed and Letters. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-25318-4.

- Mitford, Nancy (1984) [1970]. Frederick the Great. New York: E. P. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-48147-8.

- Ritter, Gerhard (1974) [1936]. Frederick the Great: A Historical Profile. Translated by Peter Peret. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Scott, Hamish (2001). The Emergence of the Eastern Powers 1756–1775. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79269-1.