Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bengkulu

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2021) |

Bengkulu (Indonesian pronunciation: [bəŋˈkulu], Rejang: ꤷꥍꥏꤰꥈꤾꥈ), historically known as Bencoolen, is a province of Indonesia. It is located on the southwest coast of Sumatra. It was formed on 18 November 1968 by separating out the area of the historic Bencoolen Residency from the province of South Sumatra under Law No. 9 of 1967 and was finalized by Government Regulation No. 20 of 1968. Spread over 20,181.53 km2, its land area is comparable to the European country of Slovenia or the U.S. state of Massachusetts or Ivanovo Oblast and it is bordered by the provinces of West Sumatra to the north, Jambi to the northeast, Lampung to the southeast, and South Sumatra to the east, and by the Indian Ocean to the northwest, south, southwest, and west.

Key Information

Bengkulu is the 28th largest province by area; it is divided into nine regencies and the city of Bengkulu, the capital and the only independent city. Bengkulu is also the 26th largest province by population in Indonesia, with 1,715,518 inhabitants at the 2010 Census[4] and 2,010,670 at the 2020 Census;[5] the official estimate as at mid 2024 was 2,115,631 (comprising 1,065,992 males and 1,020,014 females in mid 2023).[1] According to a release by Badan Pusat Statistik, it has the eleventh highest Human Development Index among the provinces, with a score of about 0.744 in 2013. By 2014, the province is positioned 28th highest in gross domestic product and 20th highest in life expectancy, 70.35 years.

Bengkulu also includes offshore Mega Island and Enggano Island in the Indian Ocean. Bengkulu has 525 kilometres of coastline along the Indian Ocean on its western side, from Dusun Baru Pelokan in Mukomuko Regency to Tebing Nasal in Kaur Regency. Bengkulu has many natural resources such as coal and gold, and has big and potential geothermal resources.[6][7] However, it is less developed than other provinces in Sumatra.

Etymology

[edit]

Traditional sources suggest that the name Bengkulu or Bangkahulu derived from the word bangkai and hulu which means 'carcasses located in a stream'. According to the story, there was once a war between small kingdoms in Bengkulu, resulting in many casualties from both sides in the streams of Bengkulu. These casualties soon rotted as they were not buried, lying in river streams. This etymology is similar to the story of a war between the Majapahit Empire and the Pagaruyung Kingdom in Padang Sibusuk, an area once ruled by the Dharmasraya empire, which also derives the name Padang Sibusuk from casualties rotting on the battlefield. During the European colonial era, the region was known as Bencoolen or British Bencoolen.[8][9]

History

[edit]

The region was subject to the Buddhist Srivijaya empire in the 8th century. The Shailendra Kingdom and Singosari Kingdom succeeded the Srivijaya but it is unclear whether they spread their influence over Bengkulu. The Majapahit also had little influence over Bengkulu.[10] There were only few smalls 'kedatuan' based on ethnicity such as in Sungai Serut, Selebar, Pat Petulai, Balai Buntar, Sungai Lemau, Sekiris, Gedung Agung and Marau Riang. It became a vassal region of the Banten Sultanate (from Western Java) in the early 15th century[10] and since the 17th century was ruled by Minangkabau's Inderapura Sultanate (today's in Pesisir Selatan, West Sumatra Province).

The first European visitors to the area were the Portuguese, followed by the Dutch in 1596. The British East India Company established a pepper-trading center and garrison at Bengkulu (Bencoolen) in 1685.[11] In 1714 the British built Fort Marlborough, which still stands. The trading post was never profitable for the British, being hampered by a location which Europeans found unpleasant, and by an inability to find sufficient pepper to buy.[citation needed] It became an occasional port of call for the EIC's East Indiamen.

In 1785, the area was integrated into British Empire as Bencoolen, while the rest of Sumatra and most of the Indonesian archipelago was part of the Dutch East Indies. Sir Stamford Raffles was stationed as Lieutenant-Governor of Bencoolen (the colony was subordinate at the time to the Bengal Presidency) from 1818 to 1824, enacting a number of reforms including the abolition of slavery, and the British presence left a number of monuments and forts in the area. Despite the difficulties of keeping control of the area while Dutch colonial power dominated the rest of Sumatra, the British persisted, maintaining their presence for roughly 140 years before ceding Bengkulu to the Dutch as part of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 in exchange for Malacca.[12] Bengkulu then remained part of the Dutch East Indies until the Japanese occupation in World War 2.

During the early 1930s, Sukarno, the future first president of Indonesia, was imprisoned by the Dutch and briefly resided in Bengkulu,[13] where he met his wife, Fatmawati. The couple had several children, including Megawati Sukarnoputri, who later became Indonesia's first female President.

After independence, Bengkulu was initially part of the 'South Sumatra' Province, which also included Lampung, the Bangka-Belitung Islands, and what is now South Sumatra itself, as a Residency. In 1968, Bengkulu gained provincial status, becoming the 26th province of Indonesia, preceding East Timor.

Bengkulu lies near the Sunda Fault and is prone to earthquakes and tsunamis. The June 2000 Enggano earthquake killed at least 100 people. A recent report predicts that Bengkulu is "at risk of inundation over the next few decades from undersea earthquakes predicted along the coast of Sumatra"[14] A series of earthquakes struck Bengkulu during September 2007, killing 13 people.[15]

Geography and climate

[edit]

The western part of Bengkulu province, bordering the Indian Ocean coast, is about 576 km along, and the eastern part of the condition is hilly with a plateau that is prone to erosion. Bengkulu Province is on the west side of the Bukit Barisan mountains. The province's area is about 20,130.21 square kilometres,or slightly smaller than the European country,Slovenia.The province extends from the border province of West Sumatra to the border province of Lampung; the distance is about 567 kilometres. Bengkulu Province lies between 2° 16' S and 03° 31' S latitude and 101° 01'-103° 41'E longitude.[16] Bengkulu province in the north borders the province of West Sumatra, in the southern the Indian Ocean and Lampung province, in the west it borders the Indian Ocean and in the east the provinces of Jambi and South Sumatra. Bengkulu province is also bordered by the Indian Ocean coastline of approximately 525 kilometres to the west. Its western part is hilly with fertile plateaus, while the western part is lowland relatively narrow, elongated from north to south and punctuated bumpy areas.

Bengkulu's climate is classified as tropical. Bengkulu has a large amount of rainfall throughout the year, even in the driest month. The climate here is classified as Af by the Köppen-Geiger system. The annual average temperature is 26.8 °C. The average annual rainfall is 3360 mm.

The total area of Bengkulu province is 20,181.53 km2. For administrative purposes, the province is divided into nine regencies and one city, together sub-divided into 93 districts.[17]

| Climate data for Bengkulu (Fatmawati Soekarno Airport, 1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 33.7 (92.7) |

35.2 (95.4) |

34.4 (93.9) |

34.8 (94.6) |

35.4 (95.7) |

34.9 (94.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.8 (92.8) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.4 (95.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.0 (87.8) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.1 (88.0) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.2 (88.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.6 (78.1) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.8 (78.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 22.3 (72.1) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.3 (72.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 20.5 (68.9) |

20.2 (68.4) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.5 (68.9) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.8 (69.4) |

18.1 (64.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 287.9 (11.33) |

222.8 (8.77) |

259.5 (10.22) |

241.1 (9.49) |

171.7 (6.76) |

133.9 (5.27) |

146.8 (5.78) |

155.4 (6.12) |

147.8 (5.82) |

210.7 (8.30) |

328.8 (12.94) |

359.9 (14.17) |

2,666.3 (104.97) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 16.5 | 13.7 | 15.4 | 13.9 | 10.7 | 9.2 | 8.6 | 9.1 | 9.3 | 13.1 | 17.0 | 19.3 | 155.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 127.0 | 133.9 | 153.8 | 163.8 | 179.7 | 175.7 | 182.9 | 185.3 | 155.0 | 136.7 | 120.3 | 111.4 | 1,825.5 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization[18] | |||||||||||||

Population

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 519,316 | — |

| 1980 | 768,064 | +47.9% |

| 1990 | 1,179,122 | +53.5% |

| 1995 | 1,409,117 | +19.5% |

| 2000 | 1,567,436 | +11.2% |

| 2010 | 1,715,518 | +9.4% |

| 2015 | 1,872,136 | +9.1% |

| 2020 | 2,010,670 | +7.4% |

| 2024 | 2,115,631 | +5.2% |

| Source: Badan Pusat Statistik[1] 2019-2024 | ||

The 2010 census reported a population of 1,715,518[4] including 875,663 males and 837,730 females;[19] by the 2020 Census this had risen to 2,010,670,[5] and the official estimate for mid 2024 was 2,115,631.[1]

Ethnic groups

[edit]

Bengkulu is home to various indigenous ethnic groups. The Rejangs form the majority of the province with 60.4% of the population. The second largest ethnic group is the Javanese forming around 24%. Other minority indigenous ethnic groups includes Lembak, Serawai, Pekal, Enggano, Pasemah, Minangkabau and Bengkulu Malays. There is also non-indigenous ethnic groups that mostly came from other parts of Indonesia such as Sundanese, Javanese, Acehnese, Madurese, Batak, Chinese and others.

Religion

[edit]

The 2022 data of Ministry of Religious Affairs found 97.69% of the population as adherents to Islam and 2% as Christian. The remainder includes Hindus (0.20%) who are mostly Balinese migrants, Buddhists (0.1%), and "other" including traditional beliefs (0.004%).[20]

Languages

[edit]Like the rest of Indonesia, Indonesian is the official language for formal occasions, institutions, and government affairs while local languages are widely used in daily life.

Most indigenous languages in Bengkulu belong to the Malayan group of Austronesian languages, such as Bengkulu Malay, Lembak, Pekal and Minangkabau varieties. The most widely spoken language in the province, Rejang, is the only Bornean language to be spoken in Sumatra (and one of three outside of Borneo other than Malagasy in Madagascar and Yakan in Basilan).

Engganese is classified as a highly divergent branch of Malayo-Polynesian, however, this is still debated.[citation needed][who?]. A less-studied language is Nasal language, which may be related to Rejang or form its own branch of Malayo-Polynesian. Non-indigenous ethnic groups also speak their own language/dialects.

Government and administrative divisions

[edit]

When it was formed in 1967 from the western parts of South Sumatra province, Bengkulu Province consisted of three regencies - Bengkulu Selatan, Bengkulu Utara and Rejang Lebong - together with the independent city of Bengkulu, which lies outside any regency. Five additional regencies were established on 25 February 2003 - Kaur Regency and Seluma Regency from parts of Bengkulu Selatan, Kepahiang Regency and Lebong Regency from parts of Rejand Lrbong Regency, and Mukomuko Regency from part of Bengkulu Utara. A ninth regency (Bengkulu Tengah) was formed on 24 June 2008 from another part of Bengkulu Utara. The regencies and city are listed below with their areas and their populations at the 2010[4] and 2020[5] Censuses, together with the official estimates as at mid 2024.[1]

| Kode Wilayah |

Name of City or Regency |

Area in km2 |

Pop'n Census 2010 |

Pop'n Census 2020 |

Pop'n Estimate mid 2024 |

Capital | HDI[21] 2014 Estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17.71 | Bengkulu City | 151.70 | 308,544 | 373,591 | 397,321 | Bengkulu | 0.764 (High) |

| 17.09 | Central Bengkulu Regency (Bengkulu Tengah) |

1,223.94 | 98,333 | 116,706 | 122,673 | Karang Tinggi | 0.641 (Medium) |

| 17.04 | Kaur Regency | 2,608.85 | 107,899 | 126,551 | 132,659 | Bintuhan | 0.637 (Medium) |

| 17.08 | Kepahiang Regency | 710.11 | 124,865 | 149,737 | 156,353 | Kepahiang | 0.652 (Medium) |

| 17.07 | Lebong Regency | 1,666.28 | 99,215 | 106,293 | 111,750 | Tubei | 0.639 (Medium) |

| 17.06 | Mukomuko Regency | 4,146.52 | 155,753 | 190,498 | 201,700 | Mukomuko | 0.653 (Medium) |

| 17.03 | North Bengkulu Regency (a) (Bengkulu Utara) |

4,424.60 | 257,675 | 296,523 | 313,521 | Arga Makmur | 0.672 (Medium) |

| 17.02 | Rejang Lebong Regency | 1,550.26 | 246,787 | 276,645 | 288,832 | Curup | 0.665 (Medium) |

| 17.05 | Seluma Regency | 2,479.36 | 173,507 | 207,877 | 217,507 | Pasar Tais | 0.629 (Medium) |

| 17.01 | South Bengkulu Regency (Bengkulu Selatan) |

1,219.91 | 142,940 | 166,249 | 173,315 | Kota Manna | 0.682 (Medium) |

| Totals | 20,181.53 | 1,715,518 | 2,010,670 | 2,115,631 | 0.680 (Medium) |

Note: (a) includes Enggano Island and neighbouring small islands in the Indian Ocean.

The province forms one of Indonesia's 84 national electoral districts to elect members to the People's Representative Council. The Bengkulu Electoral District consists of all of the 9 regencies in the province, together with the city of Bengkulu, and elects 4 members to the People's Representative Council.[22]

Economy

[edit]Three active coal mining companies produce between 200,000 and 400,000 tons of coal per year, which is exported to Malaysia, Singapore, South Asia, and East Asia.[citation needed] Fishing, particularly tuna and mackerel, is an important activity.[citation needed] Agricultural products exported by the province include ginger, bamboo shoots, and rubber.[citation needed]

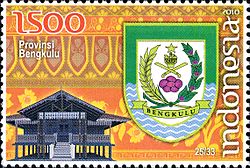

Coat of arms

[edit]The coat of arms of Bengkulu is in the shape of a shield inscribed with the word "Bengkulu". Inside the shield are a star, a cerana (traditional container), a rudus (traditional weapon), a Rafflesia arnoldii flower, and stalks of rice and coffee.

The star symbolizes belief in God Almighty. The cerana represents high culture, while the rudus signifies heroism. The Rafflesia arnoldii reflects Bengkulu’s natural uniqueness. Rice and coffee symbolize prosperity. The emblem also contains waves with 18 lines, 11 coffee leaves, six coffee flowers on each stalk, and eight stalks in total — together symbolizing 18 November 1968, the date of Bengkulu’s establishment as a province.[23]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 28 February 2025, Provinsi Bengkulu Dalam Angka 2025 (Katalog-BPS 1102001.17)

- ^ Bengkulu Lumbung Nasionalis yang Cair. February 11, 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Indeks Pembangunan Manusia 2024" (in Indonesian). Statistics Indonesia. 2024. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ a b c Biro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2011.

- ^ a b c Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2021.

- ^ EJOLT. "Bengkulu Coal-fired Power Plant, Indonesia | EJAtlas". Environmental Justice Atlas. Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ Sari, Meri Maya (2017-04-21). "Kajian Efektivitas Pelaksanaan Amdal Bidang Energi Dan Sumber Daya Mineral Dalam Pelestarian Kawasan Lindung di Kabupaten Bengkulu Tengah". Jurnal Pengelolaan Sumberdaya Alam Dan Lingkungan (Journal of Natural Resources and Environmental Management). 7 (1): 61–71. doi:10.29244/jpsl.7.1.61-71. ISSN 2086-4639.

- ^ "A History on the Honourable East India Company's Garrison on the West Coast of Sumatra 1685–1825". Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ^ "Bencoolen (Bengkulen)". Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ^ a b Schellinger, Paul; Salkin, Robert, eds. (1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places, Volume 5: Asia and Oceania. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 113. ISBN 1-884964-04-4.

- ^ "Bencoolen, Fort Marlborough of the East India Company". wftw.nl. Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 34.

- ^ "Indonesia - Toward independence | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ Andrew C. Revkin (2006-12-05). "Indonesian Cities Lie in Shadow Of Cyclical Tsunami". The New York Times (Late Edition (East Coast)) p. A.5.

- ^ "With Every Rumble, Indonesians Fear Additional Ruin (Published 2007)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2019-08-23.

- ^ "Bengkulu | province, Indonesia | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ "SEKILAS BENGKULU". PEMERINTAH PROVINSI BENGKULU (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-04-26.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Jumlah Penduduk Bengkulu 1,7 Juta Jiwa | Harian Berita Sore". Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ^ "Jumlah Penduduk Menurut Agama" (in Indonesian). Ministry of Religious Affairs. 31 August 2022. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ Indeks-Pembangunan-Manusia-2014

- ^ Law No. 7/2017 (UU No. 7 Tahun 2017) as amended by Government Regulation in Lieu of Law No. 1/2022 and Regulation of General Elections Commission No. 6/2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Lambang Bengkuluwas invoked but never defined (see the help page).

References

[edit]- Reid, Anthony (ed.). 1995. Witnesses to Sumatra: A traveller's anthology. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. pp. 125–133.

- Reprints of British-era primary source material

- Wilkinson, R.J. 1938. Bencoolen. Journal of the Malayan Branch Royal Asiatic Society. 16(1): 127–133.

- Overview of the British experience in Bencoolen

Bengkulu

View on GrokipediaName and Etymology

Etymology

The toponym Bengkulu originates from the Malay compound "Bangkahulu," where "bangkai" denotes "carcass" and "hulu" refers to "upstream" or "river head," evoking local legends of corpses from intertribal conflicts washing downstream along the region's rivers.[9][10] This folk etymology, rooted in oral traditions among Sumatran communities, underscores the area's pre-colonial history of localized warfare among petty kingdoms.[11] European colonial records adapted the name phonetically: the British East India Company, establishing a trading post in 1685, rendered it as "Bencoolen" to approximate local pronunciation while denoting their outpost on Sumatra's southwest coast.[12][13] The Dutch, acquiring the territory in 1825 via exchange with Britain, similarly used "Benkoelen," maintaining the anglicized/Dutch form in administrative documents until the mid-20th century.[12] Upon Indonesian independence in 1945, the standardized form "Bengkulu" was adopted in Bahasa Indonesia, aligning with national linguistic policies that prioritized indigenous Malay-derived terms over colonial variants for provincial nomenclature.[9] This reversion emphasized cultural continuity, with the name formalized for the province upon its creation in 1974 from South Sumatra.[9]Provincial Symbols

The coat of arms of Bengkulu Province depicts a shield with layered elements symbolizing the region's natural and cultural identity, including the Rafflesia arnoldii flower at its center to represent the endemic biodiversity unique to Sumatra's rainforests.[14] Additional motifs include rice and coffee plants signifying agricultural prosperity, a five-pointed star denoting monotheism, a crescent moon for the predominant Islamic faith, green hues for the Bukit Barisan mountain ranges, and blue waves evoking the coastal maritime heritage, with 18 waves specifically alluding to the provincial formation date. Mount Kaba, a prominent local landmark and volcano, is incorporated in the mountainous silhouette to highlight geological features.[14] The provincial flag features a solid green field with the coat of arms centered, where green denotes the fertile lands and lush vegetation supporting the province's economy.[14] Adopted alongside other symbols in the late 1960s following Bengkulu's establishment as a province on November 14, 1967, via Law No. 9 of 1967, these emblems underscore themes of unity and natural abundance.[15] The official motto, "Sekundang Setungguan Seiyo Sekato," translates to "No matter how heavy the task, if done together it feels lighter," emphasizing communal solidarity and shared prosperity as core provincial values. The seal, derived from the coat of arms, integrates maritime symbols like azure waves to reflect Bengkulu's extensive 525-kilometer coastline and historical trade significance, formalized through regional regulations post-independence.[14]History

Pre-Colonial and Early Period

The Bengkulu region on southwestern Sumatra was inhabited by Austronesian-speaking indigenous groups, including the Rejang people of Proto-Malay stock, who practiced animism and relied on swidden agriculture, hunting, and forest resource extraction for subsistence.[16] Linguistic evidence from Proto-Austronesian vowel developments in Rejang indicates deep roots in the Austronesian expansion that populated island Southeast Asia over millennia, with settlements in Sumatra dating to the Neolithic period around 2500–1500 BCE based on broader regional artifact patterns such as pottery and tools.[17] Archaeological remains, including megalithic structures on Enggano Island offshore from Bengkulu, further attest to early indigenous presence, featuring stone alignments and tombs consistent with pre-metal age traditions in Sumatra.[18] Local societies organized into decentralized village clusters governed by customary (adat) law and hereditary chiefs, fostering minimal centralization suited to the hilly terrain and reliance on kinship networks rather than large polities. These communities engaged in regional trade of forest products like resins, spices, and timber with coastal entrepôts, exchanging goods via riverine and overland routes with neighboring Sumatran groups.[19] By the 8th century, the Bengkulu area integrated into the Buddhist Srivijaya empire's thalassocratic network, a maritime power centered in southern Sumatra that dominated spice and aromatic trade routes extending to India and China, with local ports serving as peripheral nodes for pepper and camphor exports.[15] Srivijaya's influence introduced Buddhist elements and enhanced connectivity, though inland Rejang chiefdoms retained autonomy under tributary relations rather than direct rule. Following Srivijaya's decline in the 13th century amid Chola invasions and internal fragmentation, the region shifted into the orbit of the 14th-century Hindu Majapahit empire from Java, which exerted cultural and trade oversight without establishing firm territorial control, preserving indigenous adat structures amid episodic external contacts.[15]Colonial Era

The British East India Company first established a trading post at Bencoolen (present-day Bengkulu) in 1685 to secure supplies of pepper, a key commodity in European trade. Construction of Fort Marlborough, the primary defensive outpost, began in 1714 and was completed by 1719, encompassing 44,000 square meters and serving as the largest such fortification built by the Company in Southeast Asia.[12] The settlement facilitated pepper exports, yielding temporary economic surges through monopolistic trade arrangements that compelled local producers to cultivate the crop exclusively for the Company. However, persistent conflicts with indigenous groups, including raids and resistance against coercive labor practices, combined with high administrative costs and disease prevalence, rendered the venture unprofitable, with annual losses reaching £100,000 by the early 19th century.[20] Under the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, Britain transferred Bencoolen and its Sumatran dependencies to the Netherlands in exchange for Malacca, with the handover formalized on March 1, 1825.[21] Bengkulu was reorganized as the Benkoelen Residency within the Dutch East Indies, shifting colonial priorities toward broader plantation-based extraction. Dutch governance emphasized cash crop cultivation, including rubber and coffee on estates that relied on imported labor systems, though the region's rugged terrain and sparse population limited yields compared to eastern Sumatra's more intensive developments.[22] These operations perpetuated exploitative structures, such as debt bondage and forced deliveries, to maximize exports amid fluctuating global commodity prices. In February 1938, Dutch colonial authorities relocated Indonesian nationalist leader Sukarno to Bengkulu from Flores exile due to a malaria epidemic, confining him there until the Japanese occupation began in March 1942.[23] This internment underscored Bengkulu's strategic isolation for suppressing independence activism, allowing limited political engagement while monitoring Sukarno's communications and alliances, which foreshadowed broader anti-colonial mobilization.[24]Post-Independence and Modern Developments

Following Indonesia's proclamation of independence on August 17, 1945, Bengkulu was incorporated into the Republic after the end of Dutch colonial administration, initially functioning as part of the newly formed South Sumatra province in 1950. On November 18, 1968, Bengkulu was separated from South Sumatra to establish it as an independent province, marking a key administrative milestone in regional autonomy.) The province's formation reflected broader efforts to decentralize governance in Sumatra amid national consolidation post-independence. Bengkulu gained national prominence through its association with Sukarno, Indonesia's first president, who was exiled there by the Dutch from 1938 until the Japanese occupation in 1942; his residence in the city of Bengkulu remains a preserved historical site symbolizing the nationalist struggle.[23][6] During the subsequent New Order regime under Suharto (1966–1998), provincial development emphasized centralized planning from Jakarta, with subsidies supporting basic infrastructure while maintaining tight political control. In the 21st century, Bengkulu has prioritized infrastructural enhancements, including road network expansions connecting rural districts to urban centers, as highlighted in provincial initiatives to boost accessibility.[25] A notable crisis occurred in May 2025, when a widespread fuel shortage disrupted all regencies and municipalities, prompting adaptive responses from provincial authorities, including coordination with national logistics to mitigate impacts.[26] Vice President Gibran Rakabuming Raka directed accelerated dredging at Pulau Baai Port to resolve supply chain bottlenecks exacerbated by silting, demonstrating inter-level governance collaboration.[27] Presidential Instruction No. 12 of 2025 further targeted port maintenance issues affecting remote areas like Enggano Island, aiming to prevent recurrent shortages.[28]Geography and Environment

Physical Geography

Bengkulu Province occupies the southwestern coast of Sumatra island, spanning a land area of approximately 20,181 square kilometers.[29] Its western boundary fronts the Indian Ocean along a 525-kilometer coastline, while to the north it adjoins Jambi and West Sumatra provinces, and to the south, South Sumatra province.[30] The terrain transitions from low-lying coastal plains and alluvial deposits in the west to rugged highlands dominated by the Bukit Barisan mountain range in the interior, with elevations rising sharply eastward toward the central Sumatran spine.[31] Principal rivers, including the Air Ketahun and Air Kelingi, originate in the mountainous interior and flow westward across the province, discharging into the Indian Ocean and supporting drainage patterns that define the narrow riparian zones along the coast.[32] These waterways contribute to sediment deposition that sustains the coastal morphology, while the upper reaches traverse forested slopes integral to regional hydrology. Bengkulu encompasses portions of recognized biodiversity hotspots within Sumatra's tropical rainforests, harboring endemic flora such as Rafflesia arnoldii, the largest known flower species, with documented habitats across multiple districts including Kaur and South Bengkulu.[33] [34] These ecosystems thrive in the humid understory of primary and secondary forests, underscoring the province's role in preserving rare parasitic angiosperms dependent on specific liana hosts. Positioned along the Sunda subduction zone, where the Indo-Australian Plate subducts beneath the Eurasian Plate, Bengkulu experiences elevated seismic activity, including megathrust events that have historically prompted adaptive settlement in elevated or structurally resilient areas to mitigate tsunami and shaking risks.[35] [36] The Sumatran Fault system further intersects the region, amplifying intraplate seismicity and influencing geomorphic features like fault scarps and landslide-prone slopes.[37]Climate

Bengkulu province experiences a tropical monsoon climate characterized by high temperatures, elevated humidity levels averaging 80-90%, and significant seasonal rainfall variations. Average annual temperatures range from 25.6°C to 28°C across the region, with minimal diurnal or annual fluctuations due to its proximity to the equator and the Indian Ocean; daytime highs typically reach 31-32°C, while nighttime lows seldom drop below 23°C.[38][39] Annual precipitation totals approximately 2,960 mm, concentrated in the wet season from October to March, when monthly rainfall often exceeds 300 mm and can surpass 400 mm during peak months like November and December, driven by southwest monsoon winds. The dry season spans May to September, with monthly totals below 100 mm, though occasional convective showers occur due to local sea breezes from the Indian Ocean. These patterns are recorded by stations such as Fatmawati in Bengkulu City, showing consistent monsoon dominance without prolonged frost or snow.[38][40] The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) exerts notable influence on interannual variability, with positive IOD phases—marked by warmer western Indian Ocean sea surface temperatures—correlating with reduced rainfall and heightened drought risk in Bengkulu, as observed during the extreme 2019 event that caused precipitation deficits across Sumatra. Conversely, negative IOD events enhance monsoon intensity, amplifying flood-prone heavy rains, a dynamic compounded by El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) interactions that have contributed to rising air temperatures in the province.[41][42] Microclimatic differences arise between coastal lowlands and inland hilly areas in the east, where elevations up to 1,000-1,500 meters in regions like the Barisan foothills yield slightly cooler temperatures (1-2°C lower averages) and moderated rainfall due to orographic effects and reduced maritime influence. Coastal stations like Bengkulu report higher humidity and heat stress indices, while inland sites such as Polesang exhibit greater temperature variability from topographic shading and diurnal winds, as analyzed via ANOVA across BMKG-monitored locations.[43][44]Environmental Issues and Resource Management

Bengkulu Province has experienced significant deforestation, primarily driven by expansion of oil palm plantations and illegal logging activities. Satellite data from Global Forest Watch indicates that between 2001 and 2024, the province lost 477,000 hectares of tree cover, representing a 27% decline from its 2000 baseline, with associated emissions of 334 million metric tons of CO₂ equivalent.[45] This loss exceeds national averages in some periods and correlates with agricultural conversion, though enforcement challenges persist amid economic pressures for palm oil production, which provides employment but accelerates habitat degradation without commensurate reforestation gains.[45] Coastal fishing communities in Bengkulu face heightened vulnerability to climate change, exacerbated by reduced fish catches linked to shifting ocean patterns and habitat loss from upstream deforestation. Studies using livelihood vulnerability indices show that small-scale marine capture fishermen in Bengkulu City exhibit high exposure due to dependence on fisheries, with adaptive capacities limited by poverty and inadequate infrastructure, resulting in moderate overall vulnerability scores.[46] Indigenous fishers, in particular, report declining yields from phenomena like sea level rise and erratic weather, underscoring causal links between environmental degradation and socioeconomic precarity, though development in sectors like palm oil has generated jobs that partially offset income losses for some households.[47] Resource management policies emphasize sustainable practices, including village-level regulations for ecotourism in mangrove and forest areas to balance conservation with local economies. The provincial environmental and forestry services promote initiatives like mangrove tourism in Kampung Sejahtera, leveraging natural assets for revenue while aiming to curb illegal extraction, as outlined in national forest reports advocating protected area tourism.[48] However, enforcement of forest reclamation has drawn scrutiny for potential human rights issues in aggressive anti-logging operations, with 2024-2025 national data highlighting tensions between regulatory crackdowns and community reprisal claims, though empirical evidence of overregulation remains limited compared to documented illegal activities contributing to ongoing cover loss.[49]Demographics

Population Statistics

As of the 2020 Population Census conducted by Statistics Indonesia (BPS), Bengkulu Province had a total population of 2,010,670 residents.[50] The province covers an area of 19,919 km², resulting in a population density of approximately 101 inhabitants per km².[51] Annual population growth has averaged around 1.1% in recent years, driven by natural increase and net migration, leading to a projected population of approximately 2.1 million by mid-2025 based on BPS medium-variant projections.[52]| Census Year | Population | Annual Growth Rate (approx.) |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 1,715,518 | - |

| 2020 | 2,010,670 | 1.6% (2010-2020 average) |

Ethnic Groups

The ethnic composition of Bengkulu Province is diverse, reflecting indigenous groups, historical migrations, and 20th-century government transmigration efforts. Major ethnicities include the Javanese, Rejang, and Serawai, which dominate population distributions per Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS) assessments.[57] The Javanese form the largest group province-wide, stemming primarily from transmigration programs initiated under Dutch colonial rule and expanded during Indonesia's New Order era (1966–1998), with settlements spanning at least 10 regencies as of 2024.[58] The Rejang, an indigenous Proto-Malay group, represent a core highland population, concentrated in regencies such as Rejang Lebong, Lebong, Kepahiang, and northern areas of Bengkulu Utara. Numbering around 414,000 individuals nationally (largely within Bengkulu), they inhabit upland regions along the Musi River's upper reaches and uphold semi-autonomous customs, including traditional governance and rituals tied to agrarian lifestyles.[59][60] Serawai and related Lembak subgroups, also indigenous, prevail in southern and central lowlands, contributing to the province's native demographic base alongside coastal Bengkulu Malays, who trace origins to mixed Rejang, Minangkabau, and migrant influences. Minority communities include Chinese Indonesians, focused in urban trade hubs like Bengkulu City, and voluntary migrants such as Minangkabau from West Sumatra. Transmigration has spurred assimilation, with BPS long-form census data from 2020 indicating inter-ethnic mixing in urban and transmigrant settlements, though highland Rejang enclaves exhibit persistent cultural distinctiveness amid national integration policies. Ethnic tensions remain limited, with occasional resource strains in coastal fisheries noted in local surveys, but no widespread conflicts reported in recent decades.[61]Religion

Islam arrived in Bengkulu during the 15th or 16th century, primarily through trade and cultural contacts with neighboring regions such as Minangkabau and Palembang, leading to widespread conversions among local populations.[62] The predominant form is Sunni Islam, with adherence characterized by minimal syncretism with pre-Islamic animist practices, reflecting a relatively orthodox implementation following initial adoption.[62] As of 2023, over 97% of Bengkulu's population adheres to Islam, with approximately 2.03 million Muslims reported in official data derived from national surveys.[63] Christian communities, comprising Protestants and Catholics, account for less than 3% of the population, alongside negligible proportions of Hindus and Buddhists, typically under 1% combined; these minorities are largely urban-based due to migration and historical missionary activities.[63] Indonesia's Pancasila ideology mandates monotheistic belief for all citizens, ensuring formal recognition and protections for these six official religions without state favoritism toward any, though practical enforcement varies locally. Bengkulu maintains harmony among adherents through adherence to Pancasila, with no major inter-religious conflicts recorded in recent decades; local bylaws incorporate sharia-influenced elements, such as regulations on moral conduct and public behavior, but remain subordinate to national constitutional frameworks prohibiting discrimination.[64] These measures align with broader Indonesian practices post-1998 reforms, emphasizing tolerance while prioritizing the dominant Muslim demographic's preferences in community governance.[64]Languages

Indonesian serves as the official language of Bengkulu Province, functioning as the primary medium for government administration, public education, and mass media, in accordance with national policy across Indonesia. Bengkulu Malay, a dialect of the Malayic branch of Austronesian languages, acts as the dominant regional vernacular, employed in informal daily communication, particularly along the coast and in urban centers like Bengkulu City.[65] The Rejang language, spoken by the Rejang ethnic group in the province's highland interior, represents a key indigenous tongue and is noted for its distinct phonological and lexical features compared to surrounding Austronesian varieties. Provincial authorities have identified Rejang as endangered, citing reduced transmission to younger speakers amid the spread of Indonesian and Bengkulu Malay, with similar risks for the Enggano language on offshore islands.[66] Multilingual practices are routine in Bengkulu's marketplaces and trade interactions, where participants code-switch between Indonesian, Bengkulu Malay, and dialects like those of fish vendors reflecting idiolects, regional origins, and age-based variations. English usage remains limited to sporadic encounters in tourism, with no substantial integration into local commerce or vernacular speech.[67]Government and Administration

Provincial Governance

Bengkulu Province operates under Indonesia's unitary system of government, with executive authority vested in a governor elected directly by popular vote for a five-year term, renewable once. The governor, assisted by a vice governor and provincial secretariat, oversees policy implementation in devolved sectors such as public works, health, and education. The current gubernatorial term follows the simultaneous regional elections held on November 27, 2024, aligning with national decentralization practices that shifted from indirect legislative selection to direct polls starting in 2005.[68] The provincial legislature, Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah (DPRD) Bengkulu, comprises 45 members elected concurrently with gubernatorial races to represent diverse constituencies and political parties. The DPRD holds legislative powers, including approving the annual budget, enacting local regulations (perda), and conducting oversight of executive actions through commissions focused on areas like economy, welfare, and law enforcement. Membership distribution reflects electoral outcomes, with parties securing seats based on proportional representation thresholds.[69] Provincial governance traces to Bengkulu's establishment as a separate entity in 1968, carved from South Sumatra to address regional administrative needs. Post-1998 democratic reforms under laws like No. 22/1999 on Regional Government and No. 25/1999 on Fiscal Balance introduced "big bang" decentralization, devolving fiscal resources via transfers (DAU and DAK) for local priorities while mandating central oversight in security, justice, and foreign affairs. This framework has enabled Bengkulu to manage budgets exceeding routine allocations for infrastructure, though audits reveal persistent challenges in transparency and elite influence. Recent adaptations include integration of disaster risk provisions under Law No. 24/2007, reflecting the province's seismic vulnerability.[15][70][71]Administrative Divisions

Bengkulu Province is subdivided into nine regencies (kabupaten) and one autonomous city (kota), Bengkulu, which functions as the provincial capital and primary urban center.[72] The regencies include Bengkulu Selatan (capital: Manggala), Bengkulu Tengah (Karang Tinggi), Bengkulu Utara (Arga Makmur), Kaur (Bintuhan), Kepahiang (Kepahiang), Lebong (Lebong), Mukomuko (Lubuk Pinang), Rejang Lebong (Curup), and Seluma (Tais).[73] Each regency is governed by an elected bupati (regent), while the city is led by a wali kota (mayor), with terms of five years; these officials oversee local legislative councils (DPRD), budgeting, public services such as health and education, and development planning aligned with provincial and national policies.[73] These divisions exhibit significant variation in land area and economic output, reflecting diverse geographies from coastal lowlands to inland highlands. Mukomuko Regency covers the largest area at 4,829.95 km², facilitating forestry and fisheries activities, while Bengkulu City spans just 150.31 km² but houses 391,120 residents as of 2023, concentrating administrative and service functions.[72][74] Central Bengkulu Regency, encompassing 1,223.94 km² of fertile terrain, serves as an agricultural hub, contributing disproportionately to provincial rice and plantation crop production through its district-level management of irrigation and land use.[75] No major boundary adjustments have occurred since the early 2000s splits, such as the formation of Central Bengkulu from North Bengkulu in 2002, which were designed to enhance administrative efficiency and local responsiveness per Ministry of Home Affairs directives.[72]| Regency/City | Capital | Area (km², 2020) |

|---|---|---|

| Bengkulu Selatan | Manggala | 3,336.10[73] |

| Bengkulu Tengah | Karang Tinggi | 1,223.94[75] |

| Bengkulu Utara | Arga Makmur | 4,324.60[72] |

| Kaur | Bintuhan | 2,369.05[72] |

| Kepahiang | Kepahiang | 1,356.38[73] |

| Lebong | Lebong | 930.00[73] |

| Mukomuko | Lubuk Pinang | 4,829.95[73] |

| Rejang Lebong | Curup | 1,550.28[73] |

| Seluma | Tais | 2,246.90[73] |

| Bengkulu City | - | 150.31[76] |