Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Banten

View on Wikipedia

Banten (Sundanese: ᮘᮔ᮪ᮒᮨᮔ᮪, romanized: banten, Pegon: بنتن) is the westernmost province on the island of Java, Indonesia. Its capital city is Serang and its largest city is Tangerang. The province borders West Java and the Special Capital Region of Jakarta on the east, the Java Sea on the north, the Indian Ocean on the south, and the Sunda Strait (which separates Java from the neighbouring island of Sumatra) on the west and shares a maritime border with Lampung to the west. The province covers an area of 9,352.77 km2 (3,611.12 sq mi). It had a population of over 11.9 million in the 2020 census,[7] up from about 10.6 million in 2010.[8] The estimated mid-2024 population was 12,431,390, still increasing by about 106,000 people per year.[1] Formerly part of the province of West Java, Banten was split off to become a separate province on 17 October 2000.

Key Information

The northern half (particularly the eastern areas near Jakarta and the Java Sea coast) has recently experienced rapid rises in population and urbanization, and the southern half (especially the region facing the Indian Ocean) has a more traditional character but an equally fast-rising population.

Present-day Banten was part of the Sundanese Tarumanagara kingdom from the fourth to the seventh centuries AD. After the fall of Tarumanegara, it was controlled by Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms such as the Srivijaya Empire and the Sunda Kingdom. The spread of Islam in the region began in the 15th century; by the late 16th century, Islam had replaced Hinduism and Buddhism as the dominant religion in the province, with the establishment of the Banten Sultanate. European traders began arriving in the region – first the Portuguese, followed by the British and the Dutch. The Dutch East India Company, VOC (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie), finally controlled the regional economy, gradually weakening the Banten Sultanate. On 22 November 1808, Dutch Governor-General Herman Willem Daendels declared that the Sultanate of Banten had been absorbed into the Dutch East Indies.[9] This began the Bantam Residency, 150 years of direct Dutch rule. In March 1942, the Japanese invaded the Indies and occupied the region for three years before their August 1945 surrender. The region was returned to Dutch control for the next five years before the Dutch left and it was ruled by the Indonesian government. Banten became part of the province of West Java, but separatist efforts led to the creation of the separate province of Banten in October 17, 2000.[10]

Etymology

[edit]The name "Banten" has several possible origins. The first is from the Sundanese phrase katiban inten, which means "struck down by diamonds". The phrase comes from the history of the Bantenese people, who were animists before adopting Buddhism and Hinduism. After Islam began to spread in Banten, the community began to recognize and embrace Islam. The spread of Islam in Banten is described as being "struck down by diamonds".[11]

Another origin story is that the Indonesian Hindu god Batara Guru traveled from east to west, arriving at Surasowan (present-day Serang). When he arrived, Batara Guru sat on a stone which became known as watu gilang. The stone glowed, and was presented to the king of Surasowan. Surasowan was reportedly surrounded by a clear, star-like river, and was described as a ring covered with diamonds (Sundanese: ban inten). This evolved into "banten".[11]

Another possibility is that "Banten" comes from the Indonesian word bantahan (rebuttal), because the local Bantenese people resisted the Dutch colonial government.[11] The word "Banten" appeared before the establishment of the Banten Sultanate as the name of a river. The high plains on its banks were called Cibanten Girang, shortened to Banten Girang (Upper Banten). Based on research in Banten Girang, the area has been settled since the 11th and 12th centuries.[12] During the 16th century, the region developed rapidly towards Serang and the northern coast. The coastal area later became the Sultanate of Banten, founded by Sunan Gunung Jati, which controlled almost all of the former Sunda Kingdom in West Java. Sunda Kelapa (Batavia) was captured by the Dutch, and Cirebon and the Parahiyangan region were captured by the Mataram Sultanate. The Banten Sultanate was later converted into a residency by the Dutch.[11]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

During the fifth century, Banten was part of the kingdom of Tarumanagara. The fourth-century Lebak inscription, discovered in 1947 in a lowland village on the Cidanghiyang River in Munjul, Pandeglang, contains two lines of Sanskrit poetry in the Pallawa script[13] which describes life in the kingdom under the reign of Purnawarman.[14] The kingdom collapsed after an attack by Srivijaya, and western Java became part of the Sunda Kingdom. In the Chinese Chu-fan-chi, written around 1225, Chou Ju-kua wrote that Srivijaya ruled Sumatra, the Malay peninsula, and western Java during the early 13th century. Chu-fan-chi identified the port of Sunda as strategic and thriving, with pepper from Sunda among the highest quality. The population were made up of farmers, and their houses were built on wooden poles (rumah panggung). Robbery, however, was common.[15]

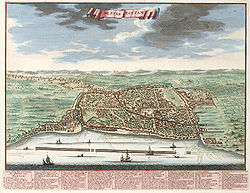

According to Portuguese explorer Tome Pires, Bantam (Banten) was an important early-16th-century port in the Kingdom of Sunda along with the ports of Pontang, Cheguide (Cigede), Tangaram (Tangerang), Calapa (Sunda Kelapa) and Chimanuk (on the Cimanuk river estuary).[16] In 1527, as the Portuguese fleet arrived off the coast, newly-converted Javanese Muslims under Sunan Gunungjati captured the port of Banten and the surrounding area from the Sundanese and established the Sultanate of Banten. According to Portuguese historian João de Barros, Banten was the center of the sultanate and a major Southeast Asian port (rivaling Malacca and Makassar). The town of Banten was in the middle of the bay, about 3 mi (4.8 km) across. It was 850 fathoms in length. A river, navigable by junks, flowed through the center of the town; a small tributary extended to the town's edge. The present-day river is smaller, and only navigable by small boats. A fortress near the town had brick walls seven palms thick. Armed, wooden defence buildings were two stories high. The town square was used for military activities and folk art, with a market in the morning. The palace was on the south side of the square. Next to the palace is a tall, flat-roofed building known as Srimanganti, which was used by the king to meet his subjects. West of the square is the Great Mosque of Banten.[citation needed]

Colonial era

[edit]

When the Dutch arrived in Indonesia, the Portuguese had long been in Banten. The English established a factory in Banten, followed by the Dutch. The French and the Danish also came to trade in Banten. In the competition among European traders, the Dutch emerged victorious. The Portuguese left Banten in 1601 after their fleet was destroyed by the Dutch off the coast during the Dutch–Portuguese War.[citation needed]

In 16th century, Chinese junk ships regularly traded with Jambi, Patani, Siam and Cambodia.[17] Local Muslim women who dealt in the cloth trade willingly married Han Chinese men in Palembang and Jambi and also local Muslim women in Banten married Han Chinese men. The Han Chinese men usually converted to Islam to please their Muslim wives.[18]

Although the Dutch won the war, they preserved the Banten Sultanate. The maritime sultanate relied on trade, and the pepper monopoly in Lampung made the Banten authorities intermediaries. The sultanate grew rapidly, becoming a commercial center.[19] As sea trade increased throughout the archipelago, Banten became a multi-ethnic region. Assisted by the British, Danish and Chinese, Banten traded with Persia, India, Siam, Vietnam, the Philippines, China and Japan.[20] The reign of Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa was the sultanate's height.[21] Under his reign, Banten had one of the strongest navies in the region, built to European standards with help from European shipbuilders and attracted Europeans to the sultanate.[22] To secure its shipping lanes, Banten sent its fleet to Sukadana (the present-day Ketapang Regency in West Kalimantan) and conquered it in 1661.[23] Banten also tried to escape the pressure of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), which had blockaded incoming merchant ships.[22]

A power struggle developed around 1680 between Ageng Tirtayasa and his son, Abu Nashar Abdul Qahar (also known as Sultan Haji). The disagreement was exploited by the VOC, who supported Haji and causing a civil war. Strengthening his position, Haji sent two envoys to meet King Charles II of England in London in 1682 to obtain support and weapons.[24] In the ensuing war, Ageng withdrew from his palace to Tirtayasa (present-day Tangerang); on 28 December 1682, the region was seized by Haji with Dutch assistance. Ageng and his other sons, Pangeran Purbaya and Syekh Yusuf from Makassar, retreated to the southern Sunda interior. On 14 March 1683, Sultan Ageng was captured and imprisoned in Batavia.[citation needed]

The VOC continued to pursue and suppress Sultan Ageng's followers, led by Prince Purbaya and Sheikh Yusuf. On 5 May 1683, the VOC sent Lieutenant Untung Surapati and his Balinese troops, joining forces led by VOC Lieutenant Johannes Maurits van Happel to subdue the Pamotan and Dayeuhluhur regions; on 14 December 1683, they captured Sheikh Yusuf.[25] Heavily outnumbered, Prince Purbaya surrendered. Surapati was ordered by Captain Johan Ruisj to pick up Purbaya and bring him to Batavia. They met with VOC forces led by Willem Kuffeler, but a dispute between them destroyed Kuffeler's forces; Surapati and his followers became fugitives from the VOC.[26]

Lampung was given to the VOC on 12 March 1682 by Sultan Haji as compensation for the company's support, and a 22 August 1682 letter gave the VOC the province's pepper monopoly.[27] The sultanate also had to reimburse the VOC for losses caused by the war.[28] After Sultan Haji's death in 1687, the VOC's influence in the sultanate began to increase; the appointment of a new sultan required the approval of the governor-general in Batavia. Sultan Abu Fadhl Muhammad Yahya ruled for about three years before he was replaced by his brother, Pangeran Adipati (Sultan Abul Mahasin Muhammad Zainul Abidin). The civil war in Banten left instability for the next government, due to dissatisfaction with the VOC's interference in local affairs.[23] Popular resistance peaked again at the end of the reign of Sultan Abul Fathi Muhammad Syifa Zainul Arifin. The sultan sought VOC assistance against the rebellion, and Banten became a vassal state of the company in 1752.[29]

In 1808, at the peak of the Napoleonic Wars, Governor-general Herman Willem Daendels ordered the construction of the Great Post Road to defend Java from British attack.[30] Daendels ordered the sultan of Banten to move his capital to Anyer and provide labor to build a port in Ujung Kulon. The sultan defied Daendels' order, and Daendels ordered an attack on Banten and the destruction of Surosowan Palace. The sultan and his family were held in the palace before their imprisonment in Fort Speelwijk. Sultan Abul Nashar Muhammad Ishaq Zainulmutaqin was then exiled to Batavia. On 22 November 1808, Daendels announced from his Serang headquarters that the sultanate had been absorbed into the Dutch East Indies.[31] The sultanate was abolished in 1813 by the British after the invasion of Java.[32] That year, Sultan Muhammad bin Muhammad Muhyiddin Zainussalihin was disarmed and forced to abdicate by Thomas Stamford Raffles; this ended the sultanate. After the British returned Java to the Dutch in 1814 as part of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814, Banten became a residentie (residency) of the Dutch East Indies.[10]

Japanese occupation and independence

[edit]

The Empire of Japan invaded the East Indies, expelling the Dutch, and occupied Banten in March 1942. During their three years of occupation, the Japanese built the Saketi–Bayah railway in southern Lebak to transport brown coal from the Bayah mines. The project involved a workforce of about 1,000 rōmusha (local forced labourers) and a few engineers and technicians (mainly Dutch), supervised by the Japanese.[33] The rōmusha working in the mines were taken from Central and East Java, the railway rōmusha were primarily from Banten. The construction took 12 million human days over 14 months.[34] Working conditions were harsh due to food shortages, lack of medical care, and the tropical climate.[35] Casualties are estimated at 20,000 to 60,000, not including mine workers.[33]

After Japan surrendered in August 1945, the Dutch East Indies declared independence as the Republic of Indonesia. This was opposed by the returning Dutch, resulting in the Indonesian war of independence. During the war, Banten remained under Indonesian control. On 26 February 1948, the State of West Java (Indonesian: Negara Jawa Barat, Sundanese: Negara Jawa Kulon) was established; on 24 April 1948, it was renamed Pasundan. Pasundan became a federal state of the United States of Indonesia in 1949, and was incorporated into the Republic of Indonesia on 11 March 1950.[36]

After Indonesian independence, Banten became part of the province of West Java. Separatist sentiment led to the creation of the province of Banten in October 17, 2000.[37]

Geography

[edit]

Banten lies between 5°7'50" and 7°1'11" south latitude and 105°1'11" and 106°7'12" east longitude.[38] The province has a land area of 9,352.77 km2 (3,611.12 sq mi).[39]

It is near the Sunda Strait's sea lanes, which link Australia and New Zealand with Southeast Asia. Banten also links Java and Sumatra. The region has a number of industries; its seaports handle overflow cargo from the seaport in Jakarta,[40] and are intended to be an alternative to the Port of Singapore.[41]

Its location on the western tip of Java makes Banten the gateway to Java, Sumatra and the adjacent areas of Jakarta, Indonesia's capital. Bordering the Java Sea on the north, the Sunda Strait on the west and the Indian Ocean on the south, the province has abundant marine resources.[42]

The land area includes some 81 offshore islands (large enough to have names) of which 50 are in Pandeglang Regency, 4 in Lebak Regency, 9 in Serang Regency, 5 in Cilegon City and 11 in Tangerang Regency.

Topography

[edit]

The province ranges in altitude from sea level to 2,000 m (6,600 ft). Banten is primarily lowland (below 50 metres above sea level) in Cilegon, Tangerang, Pandeglang Regency, and most of Serang Regency. The central Lebak and Pandeglang Regencies range from 201 to 2,000 m (659 to 6,562 ft), and the eastern Lebak Regency ranges in altitude from 501 to 2,000 m (1,644 to 6,562 ft) at the summit of Mount Halimun.

Banten's geomorphology generally consists of lowlands and sloping and steep hills.[43] The lowlands are generally in the north and south.

The sloping hills have a minimum height of 50 m (160 ft) above sea level. Mount Gede, north of Cilegon, has an altitude of 553 m (1,814 ft) above sea level; there are also hills in the southern Serang Regency, in the Mancak and Waringin Kurung Districts. The southern Pandeglang Regency is also hilly. In eastern Lebak Regency, bordering Bogor Regency and Sukabumi Regency in West Java, most of the region consists of steep hills of old sedimentary rock interspersed with igneous rocks such as granite, granodiorite, diorite and andesite. It also contains valuable tin and copper deposits.[44]

Climate

[edit]

Banten's climate is influenced by the South and East Asian Monsoons and the alternating La Niña or El Niño. During the rainy season, the weather is dominated by a west wind (from Sumatra and the Indian Ocean south of the Indian subcontinent) joined by winds from Northern Asia crossing the South China Sea. The dry season is dominated by an east wind which gives Banten severe droughts, especially on the northern coast during El Niño. Temperatures on the coast and in the hills range from 22 to 32 °C (72 to 90 °F), and temperatures in the mountains from 400 to 1,350 m (1,310 to 4,430 ft) above sea level range from 18 to 29 °C (64 to 84 °F).

The heaviest rainfall ranges from 2,712 to 3,670 mm (106.8 to 144.5 in) during the rainy season from September to May, covering half of the western Pandeglang Regency. Rainfall from 335 to 453 mm (13.2 to 17.8 in) covers half of Tangerang Regency, the northern Serang Regency, and the cities of Cilegon and Tangerang. In the dry season (from April to December), the peak rainfall of 615 to 833 mm (24.2 to 32.8 in) covers half of the northern Serang and Tangerang Regencies and the cities of Cilegon and Tangerang. The lowest dry-season rainfall, 360 to 486 mm (14.2 to 19.1 in) from June to September, covers half of the southern Tangerang Regency and 15 percent of southeastern Serang Regency.

Government and administrative divisions

[edit]Banten consists of four regencies (kabupaten) and four autonomous cities (kota), listed below with their populations in the 2010[8] and 2020 censuses[7] and the official estimates for mid-2024 as well as those projected for mid 2025.[1] The cities and regencies are subdivided into 155 districts (kecamatan) as at 2024, in turn sub-divided into 314 urban villages (kelurahan) and 1,238 rural villages (desa).

Over half (54.48% in mid 2023) of the population lives in the northeast corner of the province on just 14.6% of its land area. This corner, which comprises Tangerang Regency, Tangerang City and South Tangerang City, is part of the Jakarta metropolitan area (Jabodetabek).

| Kode Wilayah |

Name of City or regency |

Capital | Area (km2) |

Pop'n 2010 census |

Pop'n 2020 census |

Pop'n estimate mid-2024 |

Pop'n projected mid 2025 |

HDI[45] 2014 estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36.72 | Cilegon | 162.51 | 374,559 | 434,896 | 455,620 | 460,400 | 0.715 (High) | |

| 36.73 | Serang | 265.79 | 577,785 | 692,101 | 734,870 | 745,560 | 0.702 (High) | |

| 36.02 | Lebak Regency | Rangkasbitung | 3,312.18 | 1,204,095 | 1,386,793 | 1,449,210 | 1,463,820 | 0.616 (Medium) |

| 36.01 | Pandeglang Regency | Pandeglang | 2,771.41 | 1,149,610 | 1,272,687 | 1,325,950 | 1,338,370 | 0.620 (Medium) |

| 36.04 | Serang Regency | Ciruas | 1,469.91 | 1,402,818 | 1,622,630 | 1,701,800 | 1,720,320 | 0.639 (Medium) |

| Western Banten totals |

7,981.80 | 4,708,867 | 5,409,107 | 5,667,450 | 5,728,470 | |||

| 36.74 | South Tangerang | 164.86 | 1,290,322 | 1,354,350 | 1,399,500 | 1,402,160 | 0.791 (High) | |

| 36.71 | Tangerang | 178.35 | 1,798,601 | 1,895,486 | 1,963,970 | 1,971,650 | 0.758 (High) | |

| 36.03 | Tangerang Regency | Tigaraksa | 1,027.76 | 2,834,376 | 3,245,619 | 3,400,490 | 3,435,160 | 0.695 (Medium) |

| Eastern Banten totals (Greater Tangerang) |

1,370.97 | 5,923,299 | 6,495,455 | 6,763,960 | 6,808,970 | |||

| Banten totals | 9,352.77 | 10,632,166 | 11,904,562 | 12,431,390 | 12,537,440 | 0.698 (Medium) | ||

The province comprises three of Indonesia's 84 national electoral districts to elect members to the People's Representative Council. The Banten I Electoral District consists of the regencies of Pandeglang and Lebak, and elects 6 members to the People's Representative Council. The Banten II Electoral District consists of the regency of Serang, together with the cities of Ciligon and Serang, and elects 6 members to the People's Representative Council. The Banten III Electoral District consists of the regency of Tangerang, together with the cities of Tangerang and South Tangerang, and elects 10 members to the People's Representative Council.[46]

Regency capitals

[edit]Under the Law No. 2 of 1993, Tangerang was incorporated as a city on 27 February 1993 from the Tangerang Regency, of which it had been the administrative capital. It was replaced by Cipasera.

Under the Law No. 15 of 1999, Cilegon was incorporated as a city on 20 April 1999 from the Serang Regency, of which it had been the administrative capital. It was replaced by Serang.

Under the Law No. 32 of 2007, Serang was incorporated as a city on 14 August 2007 from the Serang Regency, of which it had been the administrative capital. It was replaced by Ciruas.

Under the Law No. 51 of 2008, South Tangerang (formerly Cipasera) was incorporated as a city on 26 November 2008 from the Tangerang Regency, of which it had been the administrative capital. It was replaced by Tigaraksa.

Demographics

[edit]

The 2006 population of Banten was 9,351,470, with 3,370,182 children (36.04 percent), 240,742 elderly people (2.57 percent), and the remaining 5,740,546 people aged between 15 and 64. It was Indonesia's fifth-most-populous province, after West Java, East Java, Central Java and North Sumatra. By mid-2022, the estimated total had risen to 12,251,985.[47]

Ethnic groups

[edit]

The Bantenese people are the largest group in the province, forming 47% of the total population. They mostly inhabit the central and southern part of the province. The origins of the Bantenese people; which are closely related to the Banten Sultanate, are different from the Cirebonese people whom are not part of the Sundanese people nor the Javanese people (unless it is from the result of a mixture of two major cultures, namely Sundanese and Javanese). The Bantenese people along with the Baduy people (Kanekes) are essentially a subdivision of the Sundanese people which occupies the former region of the Banten Sultanate (region of Bantam Residency after the abolishment and annexation by the Dutch East Indies). Only after the formation of the Banten Province did people began to regard the Bantenese as a group of people with a culture and language of their own.[48]

Most of the north Banten population is Javanese. Most of the Javanese are migrants from central and eastern Java. The Betawi people live in greater Jakarta, including Tangerang. Chinese Indonesians may also be found in urban areas, also primarily in the greater Jakarta area. The Benteng Chinese (a subgroup of Chinese Indonesians) lives in Tangerang and the surrounding area, and are distinct from other Chinese Indonesians.[49][50][51]

Languages

[edit]

The province's dominant language is Sundanese.[52][53] Its indigenous people speak a dialect derived from archaic Sundanese, classified as informal in modern Sundanese.[54][55]

The Mataram Sultanate tried to control West Java, including Banten; the Sultanate of Banten defended its territory except for Banten. In the mountains and most of present-day Banten, the "loma" version of the Sundanese language is dominant; this version is considered "harsh" by people from Parahyangan. Bantenese is commonly spoken, especially in the southern Pandeglang and Lebak Regencies.[56] Near Serang and Cilegon, the Javanese Banyumasan dialect is spoken by about 500,000 people.[57] In northern Tangerang, Betawi is spoken by Betawi immigrants. Indonesian is also widely spoken, especially by urban migrants from other parts of Indonesia. The Baduy people speak the Baduy language, also an archaic form of Sundanese.[58]

Religion

[edit]

Most residents are Muslims (94.85% of population),[59] and the Banten Sultanate was one of the largest Islamic kingdoms on the island of Java. The province also has other ethnicities and religions, including the Benteng Chinese community in Tangerang and the Baduy people who practice Sunda Wiwitan in Kanekes, Leuwidamar, Lebak Regency.

Based on archaeological data, early Banten society was influenced by the Hindu-Buddhist Tarumanagara, Sriwijaya and Sunda Kingdoms. According to the Babad Banten, Sunan Gunung Jati and Maulana Hasanuddin spread Islam extensively in the region. Maulana Yusuf reportedly engaged in da'wah in the interior, and conquered Pakuan Pajajaran.

The sultan of Banten's genealogy reportedly traced back to Muhammad, and the ulamas were influential. Tariqa Sufism developed in the region.

Culture

[edit]

Banten's culture is based on Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam. It includes the pencak silat martial arts, the Saman dance, and Palingtung. Religious sites include the Great Mosque of Banten and the Keramat Panjang Tomb.[citation needed]

The Baduy people live in central and southern Banten. The Inner Baduy tribes are native Sundanese who are opposed to modernization in dress and lifestyle, and the Outer Baduy tribes are more open to modernization. The Baduy-Rawayan tribe lives in the Kendeng Cultural Heritage Mountains, an area of 5,101.85 ha (19.70 sq mi) spanning the Kanekes area, Leuwidamar District, Lebak Regency. Baduy villages are generally located on the Ciujung River in the Kendeng Mountains.[60]

Weapons

[edit]The golok, similar to a machete, is Banten's traditional weapon. Formerly a self-defence weapon, it is now a martial-arts tool. The Baduy people use goloks for farming and forest hunting. Other traditional weapons include the kujang, kris, spear, sledgehammer, machete, sword and bow and arrow.

Traditional housing

[edit]Traditional housing in Banten has thatched roofing, with floors made of split and pounded bamboo. This type of traditional house is still widely found in areas inhabited by the Kanekes and Baduy peoples.

Clothing

[edit]Bantenese men traditionally wear closed-neck shirts and trousers belted with batik, perhaps with a golok tucked into the belt. Bantenese women traditionally wear a kebaya, decorated with a hand-crafted brooch at the waist. Hair is tied into a bun, and decorated with a flower.

Islamic architecture

[edit]Three-level mosque architecture is symbolic of tariqa ihsan (beauty) and sharia (law).[60]

Pencak silat

[edit]Pencak silat is a group of martial arts, rooted in Indonesian culture, which reportedly existed throughout the archipelago since the seventh century. It began to be recorded when it was influenced by the ulamas during the spread of Islam in the 15th century. At that time, martial arts were taught with religious studies in pesantren (Islamic boarding schools). Religion and pencak silat became intertwined. Silat evolved from folk dancing, becoming part of the region's defense against invaders.

Banten is known for its warriors, who are proficient in the martial arts.[60] Debus (from Arabic: دَبُّوس, romanized: dabbūs) is a Bantenese martial art which was developed during the 16th century.[61]

Tourism

[edit]

Banten is one of the favorite tourist areas in Indonesia, especially for local residents from Jakarta and West Java, especially Bogor. The Banten region, which is close to the west coast of Java Island, has a panorama located in Banten Bay such as Carita Beach, Sawarna and others as well as resort islands such as Umang and Sangiang Islands.[62] The uniqueness of the Banten community, especially the Baduy people who still maintain their ancestral customs, is also interesting to explore, as well as the rare Javan rhinoceros sanctuary in the Ujung Kulon National Park which has been designated as a world heritage site.[63] Banten also has historical tourist destinations such as the Great Mosque of Banten, the Old Banten Museum, the Multatuli Museum.

Tanjung Lesung Beach, in the Panimbang district of western Pandeglang Regency, covers about 150 ha (370 acres). A proposed special economic zone in 2012, the Tanjung Lesung SEZ became operational on 23 February 2015.[64] Pulau Dua, covering about 30 ha (74 acres) near Serang, is known for its ocean coral, fish and of birds. Between April and August each year, it is visited by about 40,000 birds from 60 species from Australia, Asia and Africa. Originally an island, sedimentation has joined it to mainland Java.[65]

Jakarta Premium Outlets is an international outlet shopping center located in Alam Sutera, Tangerang City, Indonesia. Officially opened on March 6, 2025, JPO is a joint venture between Simon Property Group and Genting Plantations Berhad. The mall features over 150 global and local brands offering daily discounts. Strategically located, it is easily accessible from Jakarta via the Jakarta–Merak Toll Road and the Jakarta Outer Ring Road (JORR).It is also considered one of the modern tourist destinations in Banten, attracting both local and international visitors.[66][67]

Transport

[edit]Banten is in western Java. In 2006, 249.246 km (155 mi) of its national roads were in good condition; 214.314 km (133 mi) were in fair condition, and 26.840 km (16.7 mi) were in poor condition. At the end of that year, 203.67 km (127 mi) of Banten's 889.01 km (552 mi) provincial road network were in good condition; 380.02 km (236 mi) were in fair condition, and 305.320 km (190 mi) were in poor condition. The province's national roads are congested; provincial roads have less traffic, and congestion is generally localized.

Rail transport is declining; 48 percent of Banten's 305.9 km (190.1 mi) rail network was operational in 2005, with an average of 22 passenger trains and 16 freight trains per day. Most lines were single-track, and the main line was the 141.6 km (88.0 mi) Merak-Tanah Abang, Tangerang-Duri, Cilegon-Cigading line, and Soekarno–Hatta Airport Rail Link serving Manggarai-Soetta Airport along with the Skytrain. Then Jakarta MRT Phase 3 with Balaraja to Cikarang, will be construction in 2024.[68][69]

Soekarno–Hatta International Airport is Indonesia's main national airport. Other airports include the general-aviation Pondok Cabe Airport in South Tangerang, Budiarto Airport in Tangerang (for training), and Gorda Airport in Serang (used by the Indonesian Air Force).

-

Soekarno–Hatta International Airport in Tangerang, gateway to Jakarta and Indonesia

-

KRL Commuterline train at the Tangerang railway station

-

Bus at Poris terminal in Tangerang

-

The Port of Merak has ferry service to Sumatra.

Economy

[edit]- Agriculture (5.09%)

- Manufacturing (30.5%)

- Other Industrial (14.6%)

- Service (49.9%)

This section needs to be updated. (January 2025) |

Banten's 2006 population totaled 9,351,470, with 36.04 percent children, 2.57 percent elderly, and the remainder 15 to 64 years old. The province's 2005 Gross Regional Domestic Product (GDP) was primarily from the manufacturing industry sector (49.75 percent), followed by the trade, hotel and restaurant sector (17.13 percent), transportation and communication (8.58 percent), and agriculture (8.53 percent). Industry had 23.11 percent of jobs, followed by agriculture (21.14 percent), trade (20.84 percent) and transportation and communication (9.5 percent). The northern part of the province is more economically developed than the southern part.

It is strategically located between Java and Sumatra. Most investment is in Tangerang, South Tangerang and the rest of the north because of their infrastructure and proximity to Jakarta. Infrastructure in southern Banten lags behind that of the north, and Banten's development policies have prioritised growth over equality in Pandeglang and Lebak regencies; investors choose areas with existing infrastructure to ensure competitiveness.

Cuisine

[edit]

Rabeg is a Bantenese food similar to goat or curried rawon. Found in Serang Regency, it is believed to have originated in the Arabian Peninsula and was brought by Arab traders during the spread of Islam in Indonesia.[71] Other Bantenese foods include nasi sumsum (from Serang Regency, made of white rice and buffalo-bone marrow), mahbub, shark fin soup, milkfish and duck satays, duck soup, laksa Tangerang, rice vermicelli, beef jerky and emping.

Sports

[edit]Football

[edit]There are multiple football clubs based in Banten. Each of them usually represent each one of Banten's regencies and cities. Two clubs are currently playing in Liga 1, Persita Tangerang and Dewa United, both play at Indomilk Arena in Tangerang regency. The rest are playing in the lower division of Indonesian football, namely Persikota Tangerang which represented the city of Tangerang with its home base at the Benteng Stadium and Persic Cilegon based at Krakatau Steel Stadium in Cilegon playing in Liga 3 while Perserang Serang (with its home ground at Maulana Yusuf Stadium) playing in Liga 2.

Motorsports

[edit]In 2009, the Lippo Village International Formula Circuit was built in a bid to host the A1 Grand Prix. The series was removed from the schedule, and the track was used for local motorsports before it was dismantled for the Lippo Village expansion; the paddock area was reclaimed by Pelita Harapan University. A replacement street circuit, BSD City Grand Prix, was built in BSD City for local motorsports.

Coat of arms

[edit]The coat of arms of Banten consists of a shield containing a mosque dome, the Great Mosque tower, the Kaibon gate, rice stalks numbering 17 grains, cotton with 8 stalks, 4 petals, and 5 flowers, a mountain, sea, gearwheel, two runway lines, a ribbon, a Javan rhinoceros, and the motto IMAN TAQWA.

The mosque dome symbolizes the religious character of Banten's people, while the five-pointed star represents belief in God Almighty. The Great Mosque tower symbolizes high spirit guided by the will of God. The Kaibon gate represents Banten as a gateway of world civilization, economy, and international traffic toward globalization. The yellow rice (17 grains) and white cotton (8 stalks, 4 brown petals, 5 flowers) symbolize Banten as an agrarian region, sufficient in food and clothing; the numbers 17-8-45 refer to the Proclamation of Indonesian Independence. The black mountain symbolizes natural wealth, lowlands, and highlands. The Javan rhinoceros symbolizes the people’s persistence in upholding truth and being protected by law. The blue sea with 17 white waves represents Banten as a maritime region rich in marine resources. The grey gearwheel (10 teeth) symbolizes the spirit of development and the industrial sector. Two white runway lines symbolize Soekarno–Hatta International Airport's runway; the yellow beacon light represents encouragement to achieve aspirations. The yellow ribbon symbolizes the unity and integrity of the Bantenese people. The Javan rhinoceros also represents the province’s identity fauna, recognized as a world heritage species.

The colors have their own meanings: red for bravery, white for purity and wisdom, yellow for glory and nobility, black for determination and perseverance, grey for resilience, blue for peace and calm, green for fertility, and brown for prosperity. The motto IMAN TAQWA (faith and piety) serves as the foundation of development towards an independent, advanced, and prosperous Banten Darussalam.

References

[edit]- "Coat of arms of Banten". Government of Banten. Archived from the original on 1 December 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2025.

Notable people

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 28 February 2025, Provinsi Banten Dalam Angka 2025 (Katalog-BPS 1102001.36)

- ^ a b "Kewarganegaraan Suku Bangsa, Agama dan Bahasa Sehari-hari Penduduk Indonesia" (PDF). www.bps.go.id. pp. 36–41. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ "Laporan Penduduk Berdasarkan Agama Provinsi Banten Semester I Tahun 2014". Biro Pemerintahan Provinsi Banten. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Badan Pusat Statistik (2023). "Produk Domestik Regional Bruto (Milyar Rupiah), 2020–2022" (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik.

- ^ Badan Pembangunan Nasional (2023). "Capaian Indikator Utama Pembangunan" (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Badan Pembangunan Nasional.

- ^ "Indeks Pembangunan Manusia 2024" (in Indonesian). Statistics Indonesia. 2024. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ a b Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2021.

- ^ a b Biro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2011.

- ^ Ekspedisi Anjer-Panaroekan, Laporan Jurnalistik Kompas. Penerbit Buku Kompas, PT Kompas Media Nusantara, Jakarta Indonesia. November 2008. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-979-709-391-4.

- ^ a b Gorlinski, Virginia. "Banten". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b c d Banten, BPCB (28 February 2017). "Banten, arti kata dan toponimi". Balai Pelestarian Cagar Budaya Banten. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Guillot, Claude, Lukman Nurhakim, Sonny Wibisono, "La principauté de Banten Girang", Archipel, 1995, Volume 50, No. 50, pp. 13-24.

- ^ OV (Oudheidkundige Verslag) 1949; 1950:20

- ^ Soekmono, Raden (1973). Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia (5th reprint ed.). Yogyakarta: Kanisius. p. 36. ISBN 9794131741. OCLC 884261720.

- ^ Soekmono, Raden (1973). Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia (5th reprint ed.). Yogyakarta: Kanisius. p. 60. ISBN 9794131741. OCLC 884261720.

- ^ Heuken, A. (1999). Sumber-sumber asli sejarah Jakarta, Jilid I: Dokumen-dokumen sejarah Jakarta sampai dengan akhir abad ke-16. Cipta Loka Caraka. p. 34.

- ^ Prakash, Om, ed. (2020). European Commercial Expansion in Early Modern Asia. An Expanding World: The European Impact on World History, 1450 to 1800. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-93871-6.

... Leur' estimate China sent out four junks to Batavia, four to Cambodia, three to Siam, one to Patani, one to Jambi, ... However, the Dutch established some control over the Chinese trade only after the destruction of Macassar in 1667 ...

- ^ Ma, Debin (2017). Textiles in the Pacific, 1500–1900. The Pacific World: Lands, Peoples and History of the Pacific, 1500-1900 (reprint ed.). Routledge. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-351-89561-3.

The Chinese, on the other hand, "bought wives" when they arrived, and, as one observer noted in Banten, these women "served them until they returned to China." In Jambi and Palembang most Chinese adopted Islam and married local women, ...

- ^ Untoro, Heriyanti Ongkodharma (2007). Kapitalisme pribumi awal Kesultanan Banten, 1522-1684 : kajian arkeologi ekonomi (in Indonesian) (1st ed.). Depok: Fakultas Ilmu Pengetahuan Budaya UI. ISBN 978-979-8184-85-7. OCLC 271724805.

- ^ Ishii, Yoneo (1998). The junk trade from Southeast Asia : translations from the Tôsen fusetsu-gaki, 1674-1723. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 981-230-022-8. OCLC 40418802.

- ^ Nana Supriatna, Sejarah, PT Grafindo Media Pratama, ISBN 979-758-601-4.

- ^ a b Guillot, C. (1990). The Sultanate of Banten. Hasan Muarif Ambary, Jacques Dumarçay. Jakarta, Indonesia: Gramedia Book Pub. Division. ISBN 979-403-922-5. OCLC 23812664.

- ^ a b Ota, Atsushi (25 June 2003). "Banten Rebellion, 1750-1752: Factors behind the Mass Participation". Modern Asian Studies. 37 (3): 613–651. doi:10.1017/S0026749X03003044. ISSN 0026-749X.

- ^ Pudjiastuti, Titik (2007). Perang, dagang, persahabatan : surat-surat Sultan Banten (1st ed.). Jakarta: Yayasan Obor Indonesia. ISBN 978-979-461-650-5. OCLC 228631545.

- ^ Azra, Azyumardi (2004). The origins of Islamic reformism in Southeast Asia : networks of Malay-Indonesian and Middle Eastern 'Ulama' in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Crows Nest, New South Wales: Asian Studies Association of Australia in association with Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-261-X. OCLC 54998728.

- ^ Kumar, Ann (1976). Surapati : man and legend : a study of three Babad traditions. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-04364-0. OCLC 3554749.

- ^ Amir Hendarsah, Cerita Kerajaan Nusantara, Great! Publisher, ISBN 602-8696-14-5.

- ^ Poesponegoro, Marwati Djoened (2008). Sejarah nasional Indonesia (Updated ed.). Jakarta: Balai Pustaka. ISBN 978-979-407-407-7. OCLC 435629543.

- ^ Ota, Atsushi (2006). Changes of regime and social dynamics in West Java : society, state, and the outer world of Banten, 1750-1830. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-15091-9. OCLC 62755670.

- ^ Pramono, Sidik (2008). Ekspedisi Anjer-Panaroekan : laporan jurnalistik Kompas : 200 tahun Anjer-Panaroekan, jalan untuk perubahan. = Expeditie Anjer-Panaroekan : journalistiek verslag van Kompas. Penerbit Buku Kompas. Jakarta: Penerbit Buku Kompas. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-979-709-391-4. OCLC 298706775.

- ^ Kartodirdjo, Sartono (1966). The peasants' revolt of Banten in 1888 : its conditions, course and sequel : a case study of social movements in Indonesia. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-94-017-6357-8. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w76vfh. OCLC 652424455.

- ^ Cribb, Robert; Kahin, Audrey (2004). Historical dictionary of Indonesia (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland.: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4935-6. OCLC 53793487.

- ^ a b Poeze, Harry A. "The Road to Hell: Construction of a Railway Line in West Java during the Japanese Occupation". In Kratoska, Paul H. (ed.). Asian Labor in the Wartime Japanese Empires. Armonk, New York: M.E.Sharpe. pp. 152–178. ISBN 978-0-7656-3335-4.

- ^ Shigeru Sato (1994). "The Bayah-Saketi Railway Construction". War, Nationalism and Peasants: Java Under the Japanese Occupation, 1942–1945. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 179–186. ISBN 978-0-7656-3907-3. OCLC 1307467455.

- ^ Bruin, Jan de; de Jager, Henk (2003). Het Indische spoor in oorlogstijd : de spoor- en tramwegmaatschappijen in Nederlands-Indië in de vuurlinie, 1873-1949 (in Dutch) (1st ed.). 's-Hertogenbosch: Uquilair. pp. 119–122. ISBN 90-71513-46-7. OCLC 66720099.

- ^ "United States of Indonesia".

- ^ Gorlinski, Virginia. "Banten". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ According to the Law of the Republic of Indonesia No. 23 (2000).

- ^ Biro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2014.

- ^ Deslatama, Yandhi. "Pemprov Banten Ajukan Enam Pelabuhan 'Pembantu' Tanjung Priok". ekonomi (in Indonesian). Jakarta: CNN Indonesia. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Banten dan Lampung Bakal Jadi Pelabuhan Penting Internasional". Redaksi Indonesia | Jernih – Tajam – Mencerahkan. 18 October 2015. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Perikanan Jadi Komoditi Andalan Provinsi Banten". SINDOnews.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Dokumen Rencana Pembangunan Daerah. "Geografi – Profil Provinsi". Website Resmi Pemerintah Provinsi Banten. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Dinas Energi dan Sumber Daya Mineral Provinsi Banten | Potensi Pertambangan". desdm.bantenprov.go.id. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Indeks-Pembangunan-Manusia-2014". Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ Law No. 7/2017 (UU No. 7 Tahun 2017) as amended by Government Regulation in Lieu of Law No. 1/2022 and Regulation of General Elections Commission No. 6/2023.

- ^ Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2023, Provinsi Banten Dalam Angka 2023 (Katalog-BPS 1102001.36)

- ^ "Suku Banten". Kebudayaan Indonesia. 26 August 2013. Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ Lohanda, Mona (1996). The Kapitan Cina of Batavia, 1837–1942: A History of Chinese Establishment in Colonial Society. Jakarta: Djambatan. ISBN 9789794282571. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ "Sejarah Cina Benteng di Indonesia !". Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Knorr, Jacqueline (2014). Creole Identity in Postcolonial Indonesia. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78238-269-0. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Language maps of Indonesia (Java and Bali)

- ^ "ECAI – Pacific Language Mapping". Archived from the original on 22 February 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Bahasa Sunda Banten". Perpustakaan Digital Budaya Indonesia. 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Purwo, Bambang K. (1993). Factors influencing comparison of Sundanese, Javanese, Madurese, and Balinese.

- ^ Parisi, Batur (16 March 2017). "Bahasa dan Sastra Sunda Banten Terancam Punah". Metro TV News. Archived from the original on 1 June 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Ethnologue. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ^ "Kewarganegaraan, Suku Bangsa, Agama, Dan Bahasa Sehari-Hari Penduduk Indonesia". Badan Pusat Statistik. 2010. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ "Jumlah Penduduk Menurut Agama" (in Indonesian). Ministry of Religious Affairs. 31 August 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ a b c Banten, Website Resmi Pemerintah Provinsi. "Kebudayaan – Profil Provinsi". Website Resmi Pemerintah Provinsi Banten. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Debus". www.indonesia.travel. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ "Umang Island". 13 August 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ "Ujung Kulon National Park". UNESCO World Heritage Convention. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ^ "Jokowi to Open Tanjung Lesung Special Economic Zone".

- ^ "Cagar Alam Pulau Dua". 13 August 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ "Jakarta Premium Outlets Resmi Dibuka, Jadi Destinasi Belanja Baru Jelang Lebaran". Suara.com. 21 March 2025. Retrieved 16 April 2025.

- ^ "Store Directory - Jakarta Premium Outlets Alam Sutera". Jakarta Premium Outlets Official Site. Retrieved 16 April 2025.

- ^ Kamalina, Annasa Rizki (23 January 2023). "Jepang Alirkan Rp160 Triliun untuk Proyek MRT Cikarang-Balaraja, Konstruksi 2024". Bisnis com.

- ^ Al Hikam, Herdi Alif (18 February 2023). "Cek! Rincian 48 Wilayah Bakal Dilewati MRT Fase 3 Cikarang-Balaraja". finance.detik.com.

- ^ "Provinsi Banten Dalam Angka 2023". Statistics Indonesia. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ "Banten Introduces Distinctive Dish at Culinary Festival". en.tempo.co. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

Further reading

[edit]External links

[edit]- Official website Archived 2 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine (in Indonesian)

Banten

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Name origins and interpretations

The name Banten is most commonly traced to the Sundanese phrase katiban inten, translating to "struck by a diamond" or "falling of a diamond," symbolizing a purported miraculous event in local lore where a diamond allegedly fell from the sky, marking a pivotal spiritual transition.[6][7] This interpretation ties to pre-Islamic eras when inhabitants practiced animism and later Buddhism, with the diamond's descent interpreted as divine intervention heralding Islam's arrival and the establishment of early settlements around the 14th century.[8][9] An alternative etymology posits derivation from the Indonesian term bantahan, meaning "rebuttal" or "objection," reflecting the historical resistance of Bantenese communities against external authorities, particularly during Dutch colonial incursions in the 16th–17th centuries when the Banten Sultanate asserted autonomy.[10] This view emphasizes the region's strategic port role and martial traditions, though it lacks the mythological depth of the katiban inten narrative and appears in fewer traditional accounts.[11] These origins remain interpretive, rooted in oral histories and early chronicles rather than archaeological evidence, with the katiban inten legend prevailing in Sundanese cultural memory as emblematic of enlightenment and resilience.[12][13]History

Pre-Islamic and early Islamic periods

The region of Banten was inhabited during the megalithic era, with archaeological evidence including menhirs and statues found in sites such as Lebak Sibedug and Cadasari in Pandeglang, indicating early settlements.[14] It subsequently fell under the influence of ancient kingdoms, beginning with Salakanagara on the west coast, followed by Tarumanagara in the 7th century, as evidenced by inscriptions like those at Munjul in Pandeglang.[14] From the 8th century, Banten formed part of the Sunda Kingdom (Pajajaran), serving as a strategic port for exporting rice and pepper to Indian, Chinese, and Persian traders under Tarumanagara and later Sunda rule.[14] Banten Girang, located along the Banten River, emerged as a key pre-Islamic political and trade center from the 10th century, populated primarily by Sundanese people and characterized by Hindu-Buddhist influences, including Shivite statues and myths centered on sacred mountains.[15] Archaeological excavations at Banten Girang reveal its role in regional commerce spanning six centuries until the 16th century, with structures and artifacts underscoring continuity in trade practices into the Islamic era.[15] As a vassal port of Pajajaran, Banten ranked second in importance to Sunda Kalapa, facilitating connections between Asia and Europe by the early 16th century.[14] Muslim traders from Arabia, India, and China had settled in Banten by 1512–1515, as recorded by Portuguese traveler Tome Pires, marking the initial phase of Islamization, which intensified after the fall of Malacca in 1511.[14] In 1525, forces from the Demak and Cirebon sultanates, led by Maulana Hasanuddin—son of Syarif Hidayatullah (Sunan Gunung Jati)—gained control of the area, initiating the shift from Hindu dominance.[14] The capital relocated to Surosowan (Banten Lama) in 1526, coinciding with the conquest of Banten Girang and the establishment of Islamic governance under Demak's protectorate.[14] Maulana Hasanuddin, appointed adipati of Banten in 1525, was formally crowned sultan in 1552, solidifying Banten as an independent Islamic kingdom and accelerating conversion among the port population.[14] This period retained pre-Islamic trade networks and symbolic elements, such as mountain-centric legitimacy myths, while Hindu priests persisted in upland areas into the mid-16th century.[15] Historical manuscripts like Sajarah Banten and Carita Purwaka Caruban Nagari corroborate these transitions, though pre-Islamic details remain challenging due to limited authentic references.[14]Sultanate of Banten

The Sultanate of Banten emerged as an independent Islamic kingdom in 1552 under Maulana Hasanuddin, who ruled until 1570 and established its capital at the port city of Banten on Java's northwest coast.[3] [14] Originally a vassal of the Pajajaran Kingdom, Banten transitioned to Islam following the spread of the faith in the region, with Hasanuddin's lineage tracing to influential religious figures that facilitated its Islamization.[14] The sultanate rapidly grew into a key entrepôt for Southeast Asian trade, particularly after Muslim merchants relocated there post the Portuguese capture of Melaka in 1511, positioning Banten as a rival hub by the mid-16th century. Economically, Banten thrived on exports of pepper, rice, and textiles, leveraging its strategic location to connect Indian Ocean networks with European and Asian markets.[3] At its zenith in the late 16th and mid-17th centuries, the sultanate controlled significant pepper production and trade routes, fostering diplomatic ties with powers like the English, French, and Danes while maintaining naval strength to protect commerce.[16] The Dutch East India Company (VOC) established a trading post in 1603, initially as partners, but competition intensified as the VOC sought monopolies on spices.[17] Relations with the VOC deteriorated amid the Anglo-Dutch Wars and internal sultanate conflicts, culminating in the 1682 Dutch conquest of Lampung's pepper lands, which undercut Banten's primary revenue source.[18] By 1686, Banten ceded control of its pepper trade to the Dutch, accelerating economic decline exacerbated by port silting and reduced deliveries after 1770.[17] [19] The 1752 treaty with the VOC further eroded sovereignty, and the sultanate persisted nominally until its dissolution by the Dutch in 1809, marking the end of its autonomy after over two centuries.[3] [20]Colonial era and European trade dominance

European traders first reached Banten in the early 16th century, with the Portuguese establishing initial contacts amid efforts to control spice routes, though Banten maintained autonomy unlike other regional ports.[21] By the late 16th century, Banten had emerged as a key exporter of pepper, leveraging its strategic position on Java's northwest coast to attract diverse merchants and facilitate trade in high-value spices that commanded premium prices in Europe.[16] The arrival of the first Dutch fleet under Cornelis de Houtman on June 27, 1596, marked the beginning of sustained Northern European involvement, as Banten's rulers sought to balance alliances for arms and goods while exporting pepper to fund military enhancements.[22] The Dutch East India Company (VOC), chartered in 1602, formalized its presence by establishing the first permanent trading post in Indonesia at Banten in 1603, focusing on securing pepper supplies amid competition with English merchants who set up a factory there in 1602.[23] Tensions escalated as the VOC pursued monopoly control; in 1619, Dutch forces seized Jayakarta from Bantenese control, renaming it Batavia and redirecting trade flows away from Banten, which undermined the sultanate's economic leverage.[24] English-Dutch rivalries culminated in the VOC expelling the English from Banten by the 1680s, further consolidating Dutch influence through naval superiority and blockades that restricted Banten's access to alternative markets.[17] Military confrontations defined the shift to European dominance, including the 1682 Dutch-Banten war, which initiated the sultanate's decline by weakening local defenses and establishing VOC oversight.[25] Subsequent rebellions, such as the 1750-1752 uprising, were suppressed by VOC forces, leading to formal overlordship by 1752 and ceding control of the pepper trade to the Dutch in 1686.[26] By the early 19th century, amid VOC bankruptcy and Napoleonic Wars disruptions, Governor-General Herman Willem Daendels dissolved the sultanate on November 22, 1808, integrating Banten into Dutch East Indies administration, ending its independent trade role.[23] This progression reflected causal dynamics of superior European naval power and commercial organization outcompeting Banten's fragmented alliances, reducing the port from a 17th-century trade hub to a peripheral outpost.[27]Japanese occupation and Indonesian independence

Japanese forces occupied Banten as part of the broader conquest of the Dutch East Indies, completing control over Java by March 9, 1942, after the Battle of the Java Sea defeated Allied naval forces.[28] The occupation administration, under the Japanese 16th Army, divided Java into three military districts, with Banten falling within West Java, emphasizing economic exploitation to support the war effort through rice requisitions, resource extraction, and labor mobilization.[29] The Japanese regime conscripted local populations, including from Banten, into romusha forced labor programs starting in 1943, deploying workers for infrastructure projects, military bases, and overseas assignments such as the Burma-Thailand railway, where conditions led to mortality rates exceeding 20% due to overwork, starvation, and tropical diseases.[30] Nationwide, 4 to 10 million Indonesians were mobilized as romusha, resulting in 200,000 to 500,000 deaths, though precise figures for Banten remain undocumented amid the archipelago-wide scope.[30] To bolster support, Japan established propaganda bodies like Putera in 1943, led by nationalists including Sukarno, and paramilitary units such as the PETA volunteer army in October 1943, training over 37,000 Javanese officers by 1945 who later aided republican forces.[28] These measures inadvertently fostered Indonesian unity and military skills, eroding Dutch prestige without significant combat resistance.[31] Japan's surrender on August 15, 1945, created a power vacuum exploited by Indonesian leaders, who proclaimed independence on August 17 in Jakarta under youth pressure.[29] In Banten, local elites, including ulama and former Japanese-trained personnel, formed committees to wrest authority from residual Japanese garrisons and Japanese-backed militias, leveraging the region's Islamic networks and historical trade autonomy for rapid organization.[27] Banten maintained republican control during the ensuing national revolution, resisting Dutch reoccupation attempts through guerrilla actions until the 1949 Round Table Conference granted sovereignty, integrating the area into the Republic of Indonesia as part of West Java.[32] Some Japanese holdouts, numbering around 900 across Indonesia, joined republican fighters in western Java, including Banten vicinities, until repatriation.

Post-independence era and provincial formation

After Indonesia's declaration of independence on August 17, 1945, and the conclusion of the national revolution with the Dutch transfer of sovereignty in December 1949, the Banten region was incorporated into the province of West Java as part of the Republic's administrative reorganization. The area, encompassing former Dutch residencies around Serang and Tangerang, primarily supported agrarian economies focused on rice, cassava, and fisheries, while its coastal ports facilitated limited trade. Local resistance during the revolution included guerrilla activities against Allied and Dutch forces, though Banten saw relatively less intense conflict compared to central Java due to its strategic proximity to Batavia (Jakarta).[33] Throughout the Sukarno and Suharto eras, Banten's integration into West Java highlighted growing disparities, with the region's distinct ethno-religious identity—marked by strong adherence to Nahdlatul Ulama traditions and pesantren networks—contrasting with the Sundanese-majority dynamics of Bandung-centered governance. Economic underdevelopment persisted, despite rapid peri-urban growth in Tangerang from Jakarta's expansion, leading to early autonomy demands in the 1950s that were sidelined under centralized policies. By the late 1990s, amid the Asian financial crisis and Suharto's resignation in May 1998, separatist sentiments intensified, driven by calls for localized resource management and cultural preservation.[34] The push culminated in Banten's formal separation from West Java under Indonesia's decentralization framework, enacted via Law No. 23 of 2000, which established the province on October 17, 2000, as the nation's 30th province. This division addressed long-standing grievances over administrative neglect and empowered local control over revenues from agriculture, manufacturing hubs, and the strategic Soekarno-Hatta International Airport in Tangerang. The new entity initially comprised four regencies—Pandeglang, Lebak, Serang, and Tangerang—and four municipalities—Cilegon, Serang, Tangerang, and Tangerang Selatan—with Serang designated as the capital to honor historical ties to the Sultanate.[35][36]Geography

Location, borders, and topography

Banten is a province located at the western end of Java island in Indonesia, spanning latitudes from approximately 5°08′S to 7°01′S and longitudes from 105°01′E to 106°07′E.[35] The province occupies a land area of 9,663 square kilometers.[37] It shares land borders with West Java province and the Special Capital Region of Jakarta to the east, while maritime boundaries include the Java Sea to the north and the Indian Ocean to the south; to the west lies the Sunda Strait, separating it from Sumatra.[38][39][40] The topography of Banten is characterized by extensive lowland coastal plains in the northern and southwestern areas, comprising the majority of the terrain below 50 meters elevation, transitioning to hilly and mountainous regions in the south-central parts, with maximum elevations reaching 2,000 meters, notably in the Ujung Kulon area.[37][41]

Climate patterns

Banten province features a tropical climate dominated by monsoon influences, with consistently high temperatures and pronounced wet-dry seasonal cycles. Year-round average temperatures hover around 26–27°C, with daily maxima typically reaching 30–32°C and minima 23–25°C; extremes rarely fall below 22°C or exceed 34°C.[42][43] Relative humidity averages 80–90%, fostering muggy conditions that persist across seasons.[43] Precipitation patterns follow the broader Indonesian monsoon regime, driven by the northwest winter monsoon (November–March), which delivers heavy rainfall averaging 200–300 mm per month, and the southeast summer monsoon (April–October), which brings drier weather with 50–100 mm monthly totals. Annual rainfall accumulates to about 2,200 mm province-wide, peaking in December–February (wettest months often exceed 300 mm) and bottoming in July–August (driest at around 50 mm).[42][44] This bimodal distribution aligns with the Köppen Aw (tropical savanna) or Af (tropical rainforest) classifications prevalent in western Java, though coastal Banten areas lean toward monsoon variability (Am subtype) due to maritime exposure.[45][46] Cloud cover is highest during the wet season (over 80% opacity), reducing sunshine to 4–5 hours daily, while the dry season sees clearer skies and 7–8 hours of sun.[44] Interannual variability, tracked by Indonesia's Badan Meteorologi, Klimatologi, dan Geofisika (BMKG), shows occasional El Niño-induced droughts or La Niña-enhanced flooding, with recent decades recording intensified wet-season peaks linked to regional warming trends of 0.1–0.2°C per decade.[47][48]Natural resources and environmental pressures

Banten's natural resources encompass a mix of minerals, forests, agricultural lands, and marine assets. The province features active mining operations, including oil and natural gas extraction, geothermal energy development, coal mining with a reported GRDP growth of 2.96% in recent quarters, and metal ore mining such as gold in districts like Cikotok and Lebak, though metal ore extraction experienced a contraction of 17.99% in the same period.[49] [50] Agricultural production includes paddy rice, fruits, and livestock, supported by fertile lowlands, while coastal fisheries leverage the Java Sea, Sunda Strait, and Indian Ocean for capture and aquaculture, contributing to national fish resource utilization where over 75% of Indonesia's stocks face full exploitation or overfishing.[51] Forested areas, including conservation zones and mangroves in Ujung Kulon National Park, provide ecosystem services like carbon sequestration, but conversion to aquaculture has led to substantial losses in carbon stocks and reduced storage capacity, with mangroves historically serving as buffers against coastal erosion.[52] [53] Environmental pressures in Banten stem primarily from industrialization, resource extraction, and climate factors. Heavy industry in Cilegon has contaminated rivers like the Ciujung with mercury from mining and manufacturing, impacting agriculture and water quality.[54] Coastal areas face plastic debris accumulation in Banten Bay, threatening marine ecosystems and fisheries sustainability.[55] Annual flooding, exacerbated by quarrying that diminishes rainwater absorption capacity and marine sand mining, affects low-lying regions, while unresolved waste management compounds urban pollution.[56] [57] Mangrove degradation and coral reef stress on islands like Tunda arise from aquaculture expansion, tourism growth, and rising sea levels, with environmental pressures including sedimentation and overexploitation reducing reef health indices.[58] [59] Ujung Kulon National Park, a biodiversity hotspot, contends with habitat fragmentation from development and potential geothermal projects, alongside broader climate vulnerabilities like extreme weather projected to intensify across Indonesia.[60] [61]Administrative divisions and government

Provincial structure and regencies

Banten Province is administratively divided into four regencies (kabupaten) and four autonomous cities (kota), a structure established when the province was separated from West Java Province by Indonesian Law No. 23 of 2000 on October 4, 2000.[62] These second-level divisions are further subdivided into 156 districts (kecamatan), 1,297 villages (desa and kelurahan), reflecting the standard hierarchical framework of Indonesian local governance under the 1999 decentralization laws.[63] The regencies generally encompass rural and semi-urban areas, while the cities function as urban administrative units with greater fiscal autonomy, each headed by a regent (bupati) for regencies or mayor (wali kota) for cities, elected every five years.[64] The regencies include Lebak Regency (capital: Rangkasbitung), Pandeglang Regency (capital: Pandeglang), Serang Regency (capital: Ciruas), and Tangerang Regency (capital: Tigaraksa).[65] The autonomous cities are Cilegon City, Serang City, Tangerang City, and South Tangerang City.[65] This configuration supports localized service delivery in areas such as education, health, and infrastructure, though disparities in development persist, with urban centers like Tangerang experiencing higher economic activity compared to rural regencies like Lebak.[66]| Division | Type | Capital | Area (km², 2023) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lebak Regency | Regency | Rangkasbitung | 3,426.56 |

| Pandeglang Regency | Regency | Pandeglang | 2,746.89 |

| Serang Regency | Regency | Ciruas | 1,469.91 |

| Tangerang Regency | Regency | Tigaraksa | 959.61 |

| Cilegon City | City | Cilegon | 162.51 |

| Serang City | City | Serang | 265.79 |

| Tangerang City | City | Tangerang | 178.35 |

| South Tangerang City | City | Tangerang Selatan | 147.19 |

Key administrative centers

Serang serves as the capital and principal administrative hub of Banten Province, hosting the offices of the governor, the Provincial People's Representative Council (DPRD), and various provincial departments responsible for policy implementation, budgeting, and oversight across the province's regencies and cities.[69] Located in the northern coastal region, approximately 75 km west of Jakarta, Serang facilitates centralized governance while connecting to surrounding areas via national highways and rail links, enabling efficient administration of public services, education, and health initiatives. The city's role extends to judicial functions through local courts and supports cultural preservation tied to Banten's historical sultanate legacy. Tangerang, the province's largest urban center with a 2020 population of 1,895,500 residents, functions as a vital secondary administrative node, particularly for economic planning and infrastructure coordination due to its adjacency to Jakarta and inclusion of key transport facilities like Soekarno-Hatta International Airport.[70] As an independent city (kota), it maintains its own municipal government handling urban development, zoning, and public utilities, while contributing to provincial revenue through industrial taxes and trade oversight in the densely populated northwest. Its administrative importance stems from managing spillover growth from the capital region, including labor migration and logistics hubs. Cilegon, situated in the northwest near the Sunda Strait, acts as a specialized administrative center for Banten's heavy industry sector, governing local regulations for manufacturing zones that produce iron, steel, and petrochemicals, which account for a significant portion of provincial exports.[71] With a 2020 population of 434,900, the city administration focuses on environmental compliance, workforce training, and port-related infrastructure at nearby Merak, supporting broader provincial goals in trade and energy security.[70] Other regency seats, such as Pandeglang in Pandeglang Regency and Tigaraksa in Tangerang Regency, handle localized administration including rural development and disaster management, but lack the scale of the major cities in influencing provincial-level decisions.[72]Local governance framework

The local governance framework in Banten operates within Indonesia's decentralized regional administration system, governed primarily by Law No. 23 of 2014 on Regional Government, which establishes provinces, regencies, cities, and villages as autonomous entities responsible for public services, development planning, and fiscal management. Banten province encompasses four regencies (kabupaten)—Lebak, Pandeglang, Serang, and Tangerang—and four cities (kota)—Cilegon, Serang, Tangerang, and South Tangerang—each led by an elected executive (regent/bupati for regencies or mayor/wali kota for cities) serving five-year terms, alongside a Regional People's Representative Council (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah, DPRD) that legislates locally and oversees the executive.[73] These elections occur simultaneously nationwide every five years, with the most recent in 2024 determining leadership until 2029.[74] Regencies and cities are subdivided into 155 districts (kecamatan), each administered by a district head (camat) appointed by the regent or mayor to coordinate service delivery, licensing, and community affairs at the sub-regency level.[75] The framework extends to the grassroots with 1,239 rural villages (desa) and 313 urban neighborhoods (kelurahan), where villages operate under Law No. 6 of 2014 on Villages, empowering elected village heads (kepala desa) with budgets from central allocations (Village Fund) for infrastructure, poverty alleviation, and participatory planning via Village Development Planning (Musrenbangdes). [76] Kelurahan heads (lurah), by contrast, are appointed and focus on administrative support in denser urban settings. This tiered autonomy emphasizes bottom-up governance, though provincial oversight ensures alignment with national standards.[73] Fiscal decentralization allocates revenues through shared taxes, transfers, and local levies, with regencies and cities deriving authority from provincial coordination via the Regional Secretary and autonomy bureaus.[77] Challenges in Banten include varying capacities across divisions, as evidenced by ongoing provincial efforts in training and monitoring under Governor Regulations like No. 45 of 2022 on organizational structures. The system prioritizes empirical service metrics, such as those tracked by the Central Statistics Agency (BPS), to evaluate performance in areas like health and education delivery.[74]Politics and controversies

Political landscape and leadership

Banten's political landscape features strong influences from national political parties, local dynasties, and coalitions that prioritize patronage networks over ideological competition. The province has historically been marked by dynastic control, exemplified by the family of former Governor Ratu Atut Chosiyah, whose tenure from 2007 to 2014 ended amid convictions for corruption involving billions of rupiah in misappropriated health insurance and housing funds.[78] This legacy has perpetuated a focus on economic and political interests among elite families, limiting broader electoral openness.[79] As of 2025, Andra Soni serves as Governor of Banten, representing the Great Indonesia Movement Party (Gerindra), with a term spanning February 20, 2025, to February 20, 2030.[80] He was elected on November 27, 2024, alongside Deputy Governor Dimyati Natakusumah, in a contest characterized by cartel politics that constrained candidate diversity through party endorsements and alliances.[81] Their victory, securing the necessary votes amid quick counts favoring coalition-backed pairs, reflects the dominance of national figures' influence, including endorsements tied to former President Joko Widodo's network, over purely local dynamics.[81] Party competition in Banten shows Gerindra's rising executive clout, building on its coalition strengths, though the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) held the largest share of legislative seats in the 2019 elections with approximately 20% of votes province-wide.[82] Legislative representation remains fragmented among 10 parties in the Provincial DPRD, but executive leadership often hinges on pragmatic alliances rather than singular dominance. Voter turnout in the 2024 pilkada exceeded 70%, driven by issues like inequality and patronage, underscoring persistent cartel arrangements that favor established networks.[83] Leadership priorities under Soni emphasize industrial growth and unemployment reduction, as evidenced by collaborations with business groups like APINDO to address economic hurdles, including a 5.33% year-on-year GDP rise in Q2 2025.[84] [85] However, governance faces ongoing challenges such as political interference in bureaucracy, corruption risks in position-selling, and demands for transparent resource allocation amid regional disparities.[86] These issues, compounded by historical pseudo-governance patterns, highlight the need for reforms to curb elite monopolies on development agendas.[87]Corruption scandals and governance failures

In 2013, Ratu Atut Chosiyah, Banten's governor from 2007 to 2014 and Indonesia's first female provincial governor, was arrested by the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) on charges of bribery related to influencing a Constitutional Court decision on a Lebak regency election dispute.[88] [89] She was convicted in 2014 of paying 1 billion rupiah (approximately $85,000 at the time) to then-Chief Justice Akil Mochtar to secure a favorable ruling, receiving a sentence of eight years imprisonment; she was released on parole in September 2022 after serving about half her term.[90] [91] This case exemplified Banten's entrenched dynastic politics, where the Chosiyah family—linked through marriage to the Ratu dynasty—allegedly controlled over 175 provincial projects valued at around $100 million, fostering opportunities for graft amid decentralized authority post-1998 reforms.[92] Ratu Atut's relatives faced parallel scrutiny, amplifying perceptions of familial corruption networks. Her younger brother, Tubagus Chaeri Wardana (known as Wawan), was convicted in July 2020 by the Jakarta Corruption Court of accepting 58 billion rupiah ($4.1 million) in bribes tied to health insurance fund mismanagement and other schemes during her tenure, receiving a seven-year sentence.[93] Additional probes revealed irregularities in housing incentive programs (Dana Perumahan) and Karangsari land acquisitions, where officials allegedly manipulated tenders and allocations for personal gain, contributing to Banten's ranking among Indonesia's provinces with the highest corruption indicators based on case volumes reported to authorities.[78] [94] Governance failures extended beyond elite scandals to systemic weaknesses, including "pseudo governance" practices where formal structures masked clientelistic control, such as "bacakan proyek" (project reading scandals) involving rigged bidding and kickbacks.[87] Decentralization amplified these issues, enabling local elites to exploit resource allocations without robust oversight, as seen in persistent political interference in decision-making and regional disparities in service delivery.[95] At the village level, a 2024 case in Gembong subdistrict highlighted ongoing vulnerabilities, where a former village head was implicated in Indonesia's largest state finance corruption scandal involving village funds, underscoring inadequate accountability in lower-tier administration.[96] These patterns reflect broader challenges in Banten's post-dynastic era, with KPK data indicating sustained corruption risks despite leadership changes.[97]Religious extremism and security challenges

Banten province has experienced religious extremism primarily through Islamist groups advocating strict interpretations of Sharia and targeting religious minorities, with roots tracing back to the Darul Islam movement that sought an Islamic state in the region during Indonesia's post-independence era.[98] This historical separatist ideology has echoed in modern networks, including Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), which has used remote areas in Banten as safe havens for recruitment, training, and funding due to socio-economic vulnerabilities like high unemployment and poverty in southern districts.[99] Vigilante organizations such as the Front Pembela Islam (FPI) have been active in Banten, engaging in intimidation, extortion, and calls for banning sects like Ahmadiyya, often framing their actions as defense of orthodox Islam against perceived deviations.[98][100] A prominent incident illustrating this extremism occurred on February 6, 2011, in Cikeusik village, Pandeglang Regency, where a mob of approximately 1,500 attackers, including members linked to radical groups, assaulted a group of Ahmadiyya Muslims, resulting in three deaths and several injuries; the violence was incited by local fatwas declaring Ahmadis heretical and culminated in convictions that drew criticism for leniency, with perpetrators receiving sentences as low as six months.[101] Such events highlight systemic intolerance, where extremist clerics and militias exploit weak enforcement of Indonesia's religious harmony regulations to justify mob justice, contributing to the displacement or closure of minority worship sites in Banten.[102] Pesantren (Islamic boarding schools) in the province, while mostly moderate, have occasionally served as vectors for radical infiltration, with studies identifying Banten as a breeding ground for JI sympathizers amid inadequate oversight and economic marginalization.[99][103] Security challenges stem from the persistence of hybrid militias blending traditional jawara (strongman) culture with Islamist ideologies, such as Pendekar Banten and Paku Banten, which number tens of thousands of members and have been implicated in electoral coercion, extortion, and alliances with radical fronts like FPI to broker political power.[98] These groups, originating from pre-Reformasi eras but surging post-1998, pose risks of localized violence during elections or religious disputes, as seen in FPI-orchestrated protests influencing Banten's 2017 gubernatorial race.[98] Although major terrorist plots in Banten remain limited compared to neighboring West Java, the province's proximity to Jakarta and underdevelopment exacerbate vulnerabilities to transnational jihadism, prompting counter-extremism efforts like anti-ISIS declarations by local networks in 2014.[98] Government responses, including FPI's 2020 dissolution, have faced challenges from rebranded iterations and uneven deradicalization in pesantren, underscoring ongoing threats to communal stability.[104][105]Demographics

Population dynamics and urbanization