Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lavrentiy Beria

View on Wikipedia

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (September 2025) |

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria[a] (29 March [O.S. 17 March] 1899 – 23 December 1953) was a Soviet politician and one of the longest-serving and most influential of Joseph Stalin's secret police chiefs, serving as head of the NKVD from 1938 to 1946, during the country's involvement in the Second World War.

Key Information

An ethnic Georgian, Beria enlisted in the Cheka in 1920, and quickly rose through its ranks. He transferred to Communist Party work in the Caucasus in the 1930s, and in 1938 was appointed head of the NKVD by Stalin. His ascent marked the end of the Stalinist Great Purge carried out by Nikolai Yezhov, whom Beria purged. After the Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, Beria organized the Katyn massacre of 22,000 Polish officers and intelligentsia, and after the occupation of the Baltic states and parts of Romania in 1940, he oversaw the deportations of hundreds of thousands of Poles, Balts, and Romanians to remote areas or Gulag camps. In 1940, Beria began a new purge of the Red Army. After Operation Barbarossa, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, he was appointed to the State Defense Committee, overseeing security.

Beria expanded the system of forced labour, mobilizing millions of Gulag prisoners into wartime production. He also was in charge of NKVD units responsible for barrier and partisan intelligence and sabotage operations on the Eastern Front. In 1943–44, Beria oversaw the mass deportations of millions of ethnic minorities from the Caucasus, actions which have been described by many scholars as ethnic cleansing or genocide. Beria was also responsible for supervising secret Gulag detention facilities for scientists and engineers, known as sharashkas. From 1945, he oversaw the Soviet atomic bomb project, to which Stalin gave priority; the project's first nuclear device was completed in 1949.[2] After the war, Beria was made a Marshal of the Soviet Union in 1945, and promoted to a full member of the Politburo in 1946.

After Stalin's death in March 1953, Beria became head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and a First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers. He also formed a troika alongside Georgy Malenkov and Vyacheslav Molotov which briefly led the country in Stalin's place.[3][4][5] However, by June 1953, Beria was removed from power in a coup organized with the support of his colleagues in the Soviet leadership and Marshal Georgy Zhukov. He was arrested, tried for treason and other offenses, and ultimately executed on 23 December 1953.

Early life and rise to power

[edit]Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria was born in Merkheuli, near Sukhumi, in the Sukhum Okrug of the Kutais Governorate (now Gulripshi District, Abkhazia, Georgia, then part of the Russian Empire). He grew up in a Georgian Orthodox family; his mother, Marta Jaqeli (1868–1955), was deeply religious and church-going. Marta was from the Guria region, descended from a noble Georgian family, and was a widow before marrying Beria's father, Pavle Beria (1872–1922), a landowner in Sukhumi Okrug, from the Mingrelian ethnic group.[6][7]

Beria attended a technical school in Sukhumi, and later claimed to have joined the Bolsheviks in March 1917 while a student in the Baku Polytechnicum (subsequently known as the Azerbaijan State Oil Academy). Beria had earlier worked for the anti-Bolshevik Mussavatists in Baku. After the Red Army captured the city on 28 April 1920, he was saved from execution because there was not enough time to arrange his shooting and replacement; it may also have been that Sergei Kirov intervened.[8] While in prison, Beria formed a connection with Nina Gegechkori (1905–1991),[9] his cellmate's niece, and they eloped on a train.[10]

In 1919, at the age of 20, Beria started his career in state security when the security service of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic hired him while he was still a student at the Polytechnicum. In 1920, he was enlisted in the Cheka, the original Bolshevik secret police, by Mir Jafar Baghirov.[11] At that time, a Bolshevik revolt took place in the Menshevik-controlled Democratic Republic of Georgia, and the Red Army subsequently invaded. The Cheka became heavily involved in the conflict, which resulted in the defeat of the Mensheviks and the formation of the Georgian SSR. Between 1922 and 1924, Beria was deputy chairman of the Georgian OGPU (as Cheka had been renamed).[12]

He then led the repression of a Georgian nationalist uprising in 1924, after which up to 10,000 people were executed.[13] Between 1924 and 1927, he was head of the secret political department of the Transcaucasian SFSR OGPU. In December 1926, he was appointed Chairman of the Georgian OGPU, and deputy chairman for the Transcaucasian OGPU.[12]

Relations with Stalin

[edit]

Beria and Joseph Stalin first met in summer 1931, when Stalin took a six-week rest in Tsqaltubo, and Beria took personal charge of his security.[16] Stalin was unimpressed by most of the local party leaders, chosen by the former Georgian party boss, Sergo Ordzhonikidze, but writing to Lazar Kaganovich in August 1932, Stalin commented that "Beria makes a good impression. He is a good organizer, an efficient, capable functionary."[17] But according to Stalin's daughter Svetlana:

He was a magnificent specimen of the artful courtier, the embodiment of Oriental perfidy, flattery and hypocrisy who had succeed[ed] in confounding even my father, a man whom it was ordinarily difficult to deceive. A good deal that this monster did is now a blot on my father's name.[18]

In October 1931, when Stalin proposed to appoint Beria Second Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party Central Committee and Second Secretary of the Transcaucasian party, the First Secretary Lavrenty Kartvelishvili exclaimed: "I refuse to work with that charlatan!"[19][page needed] Ordzhonikidze also objected to the promotion. Kartvelishvili was replaced by Mamia Orakhelashvili, who wrote to Stalin and Ordzhonikidze in August 1932 asking to be allowed to resign because he could not work with Beria as his deputy.[17] On 9 October 1932, Beria was appointed party leader for the whole Transcaucasian region. He also retained his post as First Secretary of the Georgian CP. In 1933, he promoted his old ally, Baghirov, to the head of the Azerbaijani communist party. He became a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in February 1934.

During this time, he began to attack fellow members of the Georgian Communist Party, particularly Gaioz Devdariani, who served as Minister of Education of the Georgian SSR. Beria ordered the executions of Devdariani's brothers George and Shalva. In 1935, Beria cemented his place in Stalin's entourage with a lengthy oration titled, "On the History of the Bolshevik Organisations in Transcaucasia" (later published as a book), which emphasised Stalin's role.[20] It quoted from what purported to be police reports from early in the century, which identified Stalin, under his real name Jugashvili, as the leader of the Social Democrats (Marxists) in Georgia and Azerbaijan, though as the historian Bertram Wolfe noted: "These new finds tell a different story and even speak another language from all police documents and Bolshevik reminiscences published [...] while Lenin was alive. The language sounds uncommonly like Beria's own."[21]

The Great Purge

[edit]

In the first couple of years of mass arrests of members of the Communist Party and Soviet government that began after the assassination of Leningrad party boss Sergei Kirov (1 December 1934), Beria was one of the few regional party leaders considered ruthless enough to purge the region under his control, without outside interference. On 9 July 1936, the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Armenian Communist Party, Aghasi Khanjian was found dead from a bullet wound. It was officially announced that he had committed suicide, and he was retrospectively denounced as an enemy of the people, but in 1961, the then head of the KGB, Alexander Shelepin reported that he had been murdered by Beria.[22]

On 26 December 1936, Beria summoned the head of the communist party of Abkhazia, Nestor Lakoba, to the Party headquarters in Tbilisi. Beria had Lakoba over for dinner the next day, where he was served fried trout, a favorite of Lakoba's[23] and a glass of poisoned wine.[24] They attended the opera after the dinner, watching the play Mzetchabuki (მზეჭაბუკი; "Sun-boy" in Georgian).[23] During the performance Lakoba showed the first signs of his poisoning and returned to his hotel room, where he died early the next morning.[25] Officially, Lakoba was said to have died of a heart attack, though a previous medical examination in Moscow had shown he had arteriosclerosis (thickening of the arteries), cardiosclerosis (thickening of the heart), and erysipelas (skin inflammation) in the left auricle that had led to his hearing loss.[26] His body was returned to Sukhumi, though notably all the internal organs (which could have helped identify the cause of death) were removed.[27] Lakoba was accused of "nationalist deviationism", of having helped Trotsky, and of trying to kill both Stalin and Beria.[28] With Lakoba dead, Beria effectively took control of Abkhazia and implemented a policy of "Georgification".[29]

In the months that followed Lakoba's death, members of his family were implicated on charges against the state. His two brothers were arrested on 9 April 1937, and his mother Sariya was arrested on 23 August of that year.[30] A trial of thirteen members of Lakoba's family was conducted between 30 October and 3 November 1937 in Sukhumi, with charges including counter-revolutionary activities, subversion and sabotage, espionage, terrorism, and insurgent organization in Abkhazia. Nine of the defendants, including Lakoba's two brothers, were shot on the night of 4 November.[31] Rauf, Lakoba's 15-year-old son, tried to speak to Beria, who visited Sukhumi to view the start of the trial. He was promptly arrested as well. Sariya was taken to Tbilisi and tortured in order to extract a statement implicating Lakoba, but refused, even after Rauf was tortured in front of her.[32] Sariya would die in prison in Tbilisi on 16 May 1939.[33] Rauf was sent to a labour camp, and was eventually shot in a Sukhumi prison on 28 July 1941.[34]

In December 1936, Nikolai Yezhov, the newly appointed commissar of the NKVD, the ministry which oversaw the state security and police forces, reported that more than 300 people had been arrested in Georgia in the previous few weeks.[35] In June 1937, Beria said in a speech, "Let our enemies know that anyone who attempts to raise a hand against the will of our people, against the will of the party of Lenin and Stalin, will be mercilessly crushed and destroyed."[36][page needed]

On 20 July, he wrote to Stalin to report that he had had 200 people shot, was about to submit a list of another 350 who were also to be shot, and that Shalva Eliava, Lavrenty Kartvelishvili, Maria Orakhelashvili (wife of Mamia Orakhelashvili), and numerous others had all confessed to counter-revolutionary activities but Mamia Orakhelashvili himself was holding out, though he repeatedly fainted under interrogation and had to be revived with camphor. The evidence against all of them was found, after Beria's execution, to have consisted of false confessions extracted under torture.[37] Reputedly, Orakhelashvili's ear drums were perforated and his eyes gouged out.[38]

Head of the NKVD

[edit]

In August 1938, Stalin brought Beria to Moscow as deputy head of the NKVD. Under Yezhov, the NKVD carried out the Great Purge: the imprisonment or execution of a huge number, possibly over a million, of citizens throughout the Soviet Union as alleged "enemies of the people". By 1938 the oppression had become so extensive that it was damaging the infrastructure, economy, and the armed forces of the Soviet state, prompting Stalin to wind the purge down. In September, Beria was appointed head of the Main Administration of State Security (GUGB) of the NKVD, and in November he succeeded Nikolai Yezhov as NKVD head. Yezhov was executed in 1940.

Beria's appointment marked an easing of the repression begun under Yezhov. Over 100,000 people were released from the labour camps. The government officially admitted that there had been some injustice and "excesses" during the purges, which were blamed entirely on Yezhov. The liberalization was only relative; arrests, torture, and executions continued. On 16 January 1940, Beria sent Stalin a list of 457 "enemies of the people" of whom 346 were marked to be shot. They included Yezhov and his brother and nephews; Mikhail Frinovsky and his wife and teenage son, Yefim Yevdokimov and his wife and teenage son, dozens more former NKVD officers, and the renowned writer Isaac Babel and the journalist Mikhail Koltsov.[39]

Some of the NKVD officers Beria promoted, such as Boris Rodos, Lev Shvartzman, and Bogdan Kobulov were brutal torturers who were executed in the 1950s. The theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold described being beaten on the spine and soles of his feet until "the pain was so intense that it felt as if boiling water was being poured on these sensitive areas."[40] His interrogation record was signed by Shvartzman. Robert Eikhe, a former high ranking party official, was sadistically beaten and had an eye gouged out by Rodos, in Beria's office, while Beria watched.[41] He not only permitted and encouraged the beating of prisoners, but in some cases carried it out. One prisoner who survived to give evidence in the 1950s testified that he was brought to Beria's office and accused of plotting to blow up the Moscow metro, which he denied:

Beria hit me in the face. After that, I was given 30 minutes to think in the next room, next to his office, from where the screams and groans of the beaten could be heard. An hour later, called to the office, I was met with the words of Kobulov: "What shall we start beating?"[42]

In March 1939, Beria was appointed as a candidate member of the Communist Party's Politburo. Although he did not rise to full membership until 1946, he was by then one of the senior leaders of the Soviet state. In 1941, he was made a Commissar General of State Security, the highest quasi-military rank within the Soviet police system. In 1940, the pace of the purges accelerated again. During this period, Beria supervised deportations of people identified as "political enemies" from Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia after Soviet occupation of those countries.

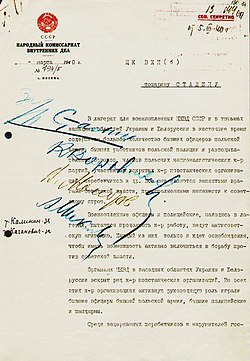

On 5 March 1940, after the Gestapo–NKVD Third Conference was held in Zakopane, Beria sent a note (No. 794/B) to Stalin in which he stated that the Polish prisoners of war kept at camps and prisons in western Belarus and Ukraine were enemies of the Soviet Union, and recommended their execution.[43] Most of them were military officers, but there were also intelligentsia, doctors, priests, and others in a total of 22,000 people. With Stalin's approval, Beria's NKVD executed them in what became known as the Katyn massacre.[44][45]

From October 1940 to February 1942, the NKVD under Beria carried out a new purge of the Red Army and related industries. In February 1941, Beria became deputy chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, and in June, following Operation Barbarossa Nazi Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union, he became a member of the State Defense Committee (GKO). During the Second World War, he took on major domestic responsibilities and mobilised the millions of people imprisoned in NKVD Gulag camps into wartime production. He took control of the manufacture of armaments, and (with Georgy Malenkov) aircraft and aircraft engines. This was the beginning of Beria's alliance with Malenkov, which later became of central importance.

In 1944, as the Soviet Union had repelled the German invasion, Beria was placed in charge of the various ethnic minorities accused of anti-sovietism and/or collaboration with the invaders, including the Balkars, Karachays, Chechens, Ingush, Crimean Tatars, Kalmyks, Pontic Greeks, and Volga Germans.[46] All these groups were deported to Soviet Central Asia.

In December 1944, the NKVD supervised the Soviet atomic bomb project ("Task No. 1"), which built and tested a bomb by 29 August 1949. The project was extremely labour-intensive. At least 330,000 people, including 10,000 technicians, were involved. The Gulag system provided tens of thousands of people for work in uranium mines and for the construction and operation of uranium processing plants. They also constructed test facilities, such as those at Semipalatinsk and in the Novaya Zemlya archipelago.

In July 1945, as Soviet police ranks were converted to a military uniform system, Beria's rank was officially converted to that of Marshal of the Soviet Union. Although he had never held a traditional military command, he made a significant contribution to the victory of the Soviet Union in the war through his organisation of wartime production and his use of partisans. Abroad, Beria had met with Kim Il Sung, the future leader of North Korea, several times when the Soviet troops had declared war on Japan and occupied the northern half of Korea from August 1945. Beria recommended that Stalin install a communist leader in the occupied territories.[47][48]

Post-war politics

[edit]With Stalin nearing 70, a concealed struggle for succession amongst his entourage dominated Soviet politics. At the end of the war, Andrei Zhdanov, who had served as the Communist Party leader in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) during the war, seemed the most likely candidate. After 1946, Beria formed an alliance with Malenkov to counter Zhdanov's rise.[49] In January 1946, Beria resigned as chief of the NKVD while retaining general control over national security matters as Deputy Prime Minister and Curator of the Organs of State Security under Stalin. However, the new NKVD chief, Sergei Kruglov, was not a supporter of Beria. Also by the summer of 1946 Beria's man, Vsevolod Merkulov, was replaced as head of the Ministry for State Security (MGB) by Viktor Abakumov.

Abakumov had headed SMERSH from 1943 to 1946; his relationship with Beria involved close collaboration (since Abakumov owed his rise to Beria's support and esteem) but also rivalry. Stalin had begun to encourage Abakumov to form his own network inside the MGB to counter Beria's dominance of the power ministries.[50] Kruglov and Abakumov moved expeditiously to replace Beria's men in the security apparatus with new people. Very soon, Deputy Minister Stepan Mamulov of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD) was the only close Beria ally left outside foreign intelligence on which Beria kept a grip.

In the following months, Abakumov started carrying out important operations without consulting Beria, often working with Zhdanov, and on Stalin's direct orders. One of the first such moves involved the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee affair, which commenced in October 1946 and eventually led to the murder of Solomon Mikhoels and the arrest of many other members. After Zhdanov died in August 1948, Beria and Malenkov consolidated their power by means of a purge of Zhdanov's associates in the so-called "Leningrad Affair". Those executed included Zhdanov's deputy, Alexey Kuznetsov; the economic chief, Nikolai Voznesensky; the Party head in Leningrad, Pyotr Popkov; and the Prime Minister of the Russian SFSR, Mikhail Rodionov.[51]

However, Beria was unable to purge Mikhail Suslov, whom he hated. Beria felt increasingly uncomfortable with Suslov's growing relationship with Stalin. Russian historian Roy Medvedev speculates in his book, Neizvestnyi Stalin, that Stalin had made Suslov his "secret heir".[52] Evidently, Beria felt so threatened by Suslov that after his arrest in 1953, documents were found in his safe labelling Suslov the No. 1 person he wanted to "eliminate".[53]

During the postwar years, Beria supervised the establishment of communist regimes in Eastern Europe and chose their Soviet-backed leaders.[54] Starting in 1948, Abakumov initiated several investigations against these leaders, which culminated with the arrest in November 1952 of Rudolf Slánský, Bedřich Geminder, and others in Czechoslovakia. These men were frequently accused of Zionism, "rootless cosmopolitanism", and providing weapons to Israel. Such charges deeply disturbed Beria, as he had directly ordered the sale of large amounts of Czech arms to Israel. Altogether, fourteen Czechoslovak communist leaders, eleven of them Jewish, were tried, convicted, and executed as part of Soviet policy to woo Arab nationalists, which culminated in the major Czech–Egyptian arms deal of 1955.[55]

The Doctors' Plot began in 1951, when a number of the country's prominent Jewish physicians were accused of poisoning top Soviet leaders and arrested. Concurrently, the Soviet press began an anti-Semitic propaganda campaign, euphemistically termed the "struggle against rootless cosmopolitanism". Initially, 37 men were arrested, but the number quickly grew into hundreds. Scores of Soviet Jews were dismissed from their jobs, arrested, sent to the Gulag, or executed. The "plot" was presumably invented by Stalin. A few days after Stalin's death on 5 March 1953, Beria freed all surviving arrested doctors, announced that the entire matter was fabricated, and arrested the MGB functionaries directly involved.

Stalin's death

[edit]Stalin's aide, Vasili Lozgachev, reported that Beria and Malenkov were the first members of the Politburo to see Stalin's condition when he was found unconscious. They arrived at Stalin's dacha at Kuntsevo at 03:00 on 2 March 1953, after being called by Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin. The latter two did not want to risk Stalin's wrath by entering his private rooms.[56] Lozgachev tried to explain to Beria that the unconscious Stalin (still in his soiled clothing) was "sick and needed medical attention". Beria angrily dismissed his claims as panic-mongering and quickly left, ordering him, "Don't bother us, don't cause a panic and don't disturb Comrade Stalin!"[57] Alexsei Rybin, Stalin's bodyguard, recalled, "No one wanted to telephone Beria, since most of the personal bodyguards hated Beria".[58]

Calling a doctor was deferred for a full twelve hours after Stalin was rendered paralysed, incontinent, and unable to speak. This decision is noted as "extraordinary" by the historian Simon Sebag Montefiore, but also consistent with the standard Stalinist policy of deferring all decision-making (no matter how crucial or obvious) without official orders from a higher authority.[59] Beria's decision to avoid immediately calling a doctor was tacitly supported (or at least not opposed) by the rest of the Politburo, which was rudderless without Stalin's micromanagement and paralysed by a legitimate fear that he would suddenly recover and take reprisals on anyone who had dared to act without his orders.[60] Stalin's suspicion of doctors in the wake of the Doctors' Plot was well known at the time of his sickness; his private physician was being tortured in the basement of the Lubyanka for suggesting the leader required more bed rest.[61] Khrushchev wrote in his memoirs that immediately after Stalin's stroke, Beria had gone about "spewing hatred against [Stalin] and mocking him". When Stalin showed signs of consciousness, Beria dropped to his knees and kissed his hand. When Stalin fell unconscious again, Beria immediately stood and spat.[62]

After Stalin's death on 5 March 1953, Beria's ambitions sprang into full force. In the uneasy silence following the cessation of Stalin's last agonies, he was the first to dart forward to kiss his lifeless form (a move likened by Montefiore to "wrenching a dead King's ring off his finger").[63] While the rest of Stalin's inner circle (even Molotov, saved from certain liquidation) stood sobbing unashamedly over the body, Beria reportedly appeared "radiant", "regenerated", and "glistening with ill-concealed relish".[63] When Beria left the room, he broke the sombre atmosphere by shouting loudly for his driver, his voice echoing with what Stalin's daughter Svetlana Alliluyeva called "the ring of triumph unconcealed".[64] Alliluyeva noticed how the Politburo seemed openly frightened of Beria and unnerved by his bold display of ambition. "He's off to take power", Mikoyan recalled muttering to Khrushchev. That prompted a "frantic" dash for their own limousines to intercept him at the Kremlin.[64]

Stalin's death prevented a final purge of the Old Bolsheviks, Mikoyan and Molotov, for which Stalin had been laying the groundwork in the year prior to his death. Shortly after Stalin's death, Beria announced triumphantly to the Politburo that he had "done [Stalin] in" and "saved [us] all", according to Molotov's memoirs. The assertion that Stalin was poisoned by Beria's associates has been shared by Edvard Radzinsky and other authors.[61] From 1939 to 1953, the Soviet Poison Laboratory was under the supervision of Beria and his deputy Vsevolod Merkulov[citation needed].[65][page needed] According to Radzinsky, Stalin was poisoned by a senior bodyguard.[66][page needed][67][68] Beria's son, Sergo Beria, later recounted that after Stalin's death, his mother Nina told her husband that, "Your position now is even more precarious than when Stalin was alive".[69] Some authors have claimed that Stalin "may have been poisoned" using the anticoagulant warfarin, although others have argued that "the description we have of Stalin's illness does not match the appearance or timeline of patients that experience severe warfarin or warfarin-related overdoses".[68][70] Towards the end of his life, Stalin was "obsessive about the possibility of being poisoned" and that given his paranoia, "it is difficult to imagine a scenario where Beria or another conspirator could have slipped an anticoagulant into his drink".[70]

First Deputy Premier and triumvirate

[edit]After Stalin's death, Beria was appointed First Deputy Premier and reappointed head of the MVD, which he merged with the MGB. His close ally Malenkov was the new Premier and initially the most powerful man in the post-Stalin leadership. Beria was second-most powerful, and given Malenkov's weakness, was poised to become the power behind the throne and ultimately leader.[according to whom?] Khrushchev became Party Secretary and Kliment Voroshilov became Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (the nominal head of state).

Beria undertook some measures of liberalisation immediately after Stalin's death.[71] He reorganised the MVD and drastically reduced its economic power and penal responsibilities. A number of costly construction projects, such as the Salekhard–Igarka Railway, were scrapped, and the remaining industrial enterprises became affiliated under other economic ministries.[72] The Gulag system was transferred to the Ministry of Justice, and a mass release of over a million prisoners was announced, although only prisoners convicted for "non-political" crimes were released.[73] That amnesty led to a substantial increase in crime and would later be used against Beria by his rivals.[74][75]

To consolidate power, Beria also took steps to recognise the rights of non-Russian nationalities. As a Georgian, he questioned the traditional policy of Russification and encouraged local officials to assert their own identities. He first turned to Georgia, where Stalin's fabricated Mingrelian affair was called off and the republic's key posts were filled by pro-Beria Georgians.[76] Beria's policies of granting more autonomy to the Ukrainian SSR alarmed Khrushchev, for whom Ukraine was a power base. Khrushchev then tried to draw Malenkov to his side, warning that "Beria is sharpening his knives".[77]

Khrushchev opposed the alliance between Beria and Malenkov, but he was initially unable to challenge them. Khrushchev's opportunity came in June 1953 when the East German uprising of 1953 against the East German communist regime broke out in East Berlin. Based on Beria's statements, other leaders suspected that in the wake of the uprising he would consider trading the reunification of Germany and the end of the Cold War for support from the United States, as had been received in the Second World War.

The cost of the war still weighed heavily on the Soviet economy. Beria craved the vast financial resources that another (more sustained) relationship with the U.S. could provide. According to some later sources, he ostensibly even considered giving the Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian SSRs "serious prospects of national autonomy", possibly similar to the Soviet satellite states in Europe.[78][79][page needed][80] Beria said of East Germany, "It is not even a real state but one kept in being only by Soviet troops".[13] The East German uprising convinced Molotov, Malenkov and Bulganin that Beria's policies were dangerous and destabilizing to Soviet power.

On 21 June 1953, Khrushchev was contacted by MVD Chief Timofei Strokach, a wartime colleague of his, who warned him that Beria was preparing for a coup in Moscow and had threatened him, saying "we shall expel you from the MVD, arrest you, and allow you to rot in the camps". He claimed that Beria intended to send special MVD divisions to Moscow to help him seize power, and that several MVD agents had boasted that the MVD would become independent of Party bodies and "a regional MVD chief would no longer be answerable to the Party secretary". Within days, Khrushchev persuaded the other leaders to support a coup d'etat against Beria.[81]

Arrest, trial and execution

[edit]

Beria, as first deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers and an influential Politburo member, saw himself as Stalin's successor, while wider Politburo members had contrasting thoughts on the leadership. On 26 June 1953, Beria was arrested and held in an undisclosed location near Moscow. Accounts of his downfall vary considerably. The historical consensus is that Khrushchev prepared an elaborate ambush, convening a meeting of the Presidium on 26 June, where he suddenly launched a scathing attack on Beria, accusing him of being a traitor and spy in the pay of British intelligence agencies. Beria was taken completely by surprise. He asked, "What's going on, Nikita Sergeyevich? Why are you picking fleas in my trousers?" When Beria finally realised what was happening and plaintively appealed to Malenkov to speak for him, Malenkov silently hung his head and pressed a button on his desk. This was an arranged signal to Marshal Georgy Zhukov and a group of armed officers in a nearby room, who burst in and arrested Beria.[b]

As Beria's men were guarding the Kremlin, he was held there in a special cell until nightfall and then smuggled out in the trunk of a car.[83] He was taken first to the Moscow guardhouse and then to the bunker of the headquarters of the Moscow Military District.[84] Defence Minister Bulganin ordered the Kantemirovskaya Tank Division and Tamanskaya Motor Rifle Division to move into Moscow to prevent security forces loyal to Beria from rescuing him. Many of Beria's subordinates, proteges, and associates were also arrested and later executed, among them Merkulov, Bogdan Kobulov, Sergo Goglidze, Vladimir Dekanozov, Pavlo Meshyk, and Lev Vlodzimirsky.

Following Beria's arrest, the Politburo issued a decree formally removing him from his posts as a "traitor and capitalist agent" and accused him and his co-defendants of attempting to place the MVD above the party in a bid to seize power and liquidate the Soviet regime. A Pravda editorial on 10 July repeated these charges and made other accusations, claiming that Beria had caused food shortages by undermining the Soviet collective farm system, and claimed his policies of liberalization (in which a number of Russian officials in Latvia were dismissed from their posts) were meant to incite ethnic hatred and undermine the friendship of the Soviet people.[85][86]

Vyacheslav Malyshev succeeded Beria as head of the Soviet nuclear weapons project. After a review of project documentation during the summer of 1953 it was found that Beria had started thermonuclear weapons development without approval from the Central Committee, which was "shocked" by the revelation. Beria had even scratched out the signature block for Malenkov's signature and signed it himself. "Evidently Beria had been confident enough of his ascent to power to assume that he would command sole authority by the time the thermonuclear design was ready to be tested".[87]

Beria and his men were tried by a "special session" (специальное судебное присутствие) of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union on 23 December 1953 with no defence counsel and no right of appeal. Marshal Ivan Konev was the chairman of the court.[88][89] Beria was found guilty of:

- Treason. It was alleged that he had maintained secret connections with foreign intelligence services. In particular, attempts to initiate peace talks with Adolf Hitler in 1941 through the ambassador of the Kingdom of Bulgaria were classified as treason, though Beria had been acting on the orders of Stalin and Molotov. It was also alleged that Beria, who in 1942 helped organise the defence of the North Caucasus, tried to let the Germans occupy the Caucasus. Beria's suggestion to his assistants that to improve foreign relations it was reasonable to transfer the Kaliningrad Oblast to Germany, part of Karelia to Finland, the Moldavian SSR to Romania, and the Kuril Islands to Japan also formed part of the allegations against him.

- Terrorism. Beria's participation in the purge of the Red Army in 1941 was classified as an act of terrorism.

- Counter-revolutionary activity during the Russian Civil War. In 1919, Beria worked in the security service of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. Beria maintained that he was assigned to that work by the Hummet party, which subsequently merged with the Adalat Party, the Ahrar Party, and the Baku Bolsheviks to establish the Azerbaijan Communist Party.

Beria and all the other defendants were sentenced to death on the day of the trial. The other six defendants – Dekanozov, Merkulov, Vlodzimirsky, Meshik, Goglidze, and Kobulov – were shot immediately after the trial ended.[90] Beria was executed separately; he allegedly pleaded on his knees before collapsing to the floor wailing.[91] He was shot through the forehead by General Pavel Batitsky.[92] His final moments bore great similarity to those of his predecessor, Nikolai Yezhov, who begged for his life before his execution in 1940.[93] Beria's body was cremated and the remains buried in Communal Grave No. 3 at Donskoye Cemetery in Moscow.[94] Beria's personal archive (said to have included "compromising" material on his former colleagues) was destroyed on Khrushchev's orders.[95]

Sexual predation

[edit]At Beria's trial in 1953, it became known that he had committed numerous rapes during the years he was NKVD chief.[96] Montefiore concludes that the information "reveals a sexual predator who used his power to indulge himself in obsessive depravity".[97] Despite evidence, charges of sexual abuse were disputed by his wife Nina and their son Sergo.[98]

According to the testimony of Colonel Rafael Semyonovich Sarkisov and Colonel Sardion Nikolaevich Nadaraia – two of Beria's bodyguards – on warm nights during the war, Beria was often driven around Moscow in his limousine. He would point out young women that he wanted to be taken to his dacha, where wine and a feast awaited them. After dining, Beria would take the women into his soundproofed office and rape them. An American report from 1952 quoted a former Muscovite as having "learned from one of Beria's mistresses that it was Beria's habit to order various women to become intimate with him and that he threatened them with prison if they refused".[99]

His bodyguards reported that their duties included handing each victim a flower bouquet as she left the house. Accepting it implied that the sex had been consensual; refusal would mean arrest. Sarkisov reported that after one woman rejected Beria's advances and ran out of his office, Sarkisov mistakenly handed her the flowers anyway. The enraged Beria declared, "Now, it is not a bouquet, it is a wreath! May it rot on your grave!" The NKVD arrested the woman the next day.[97]

According to the historian Amy Knight, rumors about Beria's behavior had been circulating around Moscow, with post-war US embassy employee Edward Ellis Smith claiming that "Beria's escapades were common knowledge among embassy personnel because his house was on the same street as a residence for Americans, and those who lived there saw girls brought to Beria's house late at night in a limousine".[100]

Women also submitted to Beria's sexual advances in exchange for the promise of freedom for imprisoned relatives. In one case, Beria picked up Tatiana Okunevskaya, a well-known Soviet actress, under the pretence of bringing her to perform for the Politburo. Instead he took her to his dacha, where he offered to free her father and grandmother from prison if she submitted. He then raped her, telling her, "Scream or not, it doesn't matter". In fact, Beria knew that Okunevskaya's relatives had been executed months earlier. Okunevskaya was arrested shortly afterwards and sentenced to solitary confinement in the gulag, which she survived.[101]

Stalin and other high-ranking officials came to distrust Beria.[102] In one instance, when Stalin learned that his teenage daughter, Svetlana, was alone with Beria at his house, he telephoned her and told her to leave immediately. When Beria complimented Alexander Poskrebyshev's daughter on her beauty, Poskrebyshev quickly pulled her aside and instructed her, "Don't ever accept a lift from Beria".[103] After taking an interest in Kliment Voroshilov's daughter-in-law during a party at their summer dacha, Beria shadowed their car closely all the way back to the Kremlin, terrifying his wife.[102]

Before and during the war, Beria directed Sarkisov to keep a list of the names and phone numbers of the women that Beria had sex with. Eventually, he ordered Sarkisov to destroy the list as a security risk, but Sarkisov retained a secret copy. When Beria's fall from power began, Sarkisov passed the list to Viktor Abakumov, the former wartime head of SMERSH and now chief of the MGB – the successor to the NKVD. Abakumov was already building a case against Beria. Stalin, who was also seeking to undermine Beria, was thrilled by the detailed records kept by Sarkisov, demanding, "Send me everything this asshole writes down!"[101] In 2003, the Russian government acknowledged Sarkisov's handwritten list of Beria's victims, which reportedly contains hundreds of names. The victims' names were also released to the public in 2003.[104]

Evidence suggests that Beria also murdered some of the women. In 1993, construction workers installing streetlights unearthed human remains near Beria's former Moscow villa (now the Tunisian embassy), which included skulls, pelvises and leg bones.[105] More were found at the site in 1998, when the skeletal remains of five young women were discovered during work carried out on the water pipes in the villa's garden.[106] In 2011, building workers digging a ditch in Moscow city centre unearthed a common grave near the same residence containing a pile of human bones, including two children's skulls covered with lime or chlorine. The lack of articles of clothing and the condition of the remains indicate that these bodies were buried naked.[citation needed]

According to Martin Sixsmith, in a BBC documentary, "Beria spent his nights having teenagers abducted from the streets and brought here for him to rape. Those who resisted were strangled and buried in his wife's rose garden".[107] Vladimir Zharov, head of the Department of Forensic Medicine at Moscow State University and then the head of the criminal forensics bureau, said a torture chamber existed in the basement of Beria's villa and that there was probably an underground passage to burial sites.[105]

Honours and awards

[edit]Beria was stripped of all titles and awards on 23 December 1953.[108]

Soviet Union

[edit]- Hero of Socialist Labour (1943)

- Order of Lenin (1935, 1943, 1945, 1949, 1949)

- Order of the Red Banner (1924, 1942, 1944)

- Order of Suvorov, 1st class (1944)

- Medal "For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (1945)

- Medal "For the Defence of Stalingrad" (1942)

- Medal "For the Defence of Moscow" (1944)

- Medal "For the Defence of the Caucasus" (1944)

- Jubilee Medal "30 Years of the Soviet Army and Navy" (1948)

- Medal "In Commemoration of the 800th Anniversary of Moscow" (1947)

- Honorary State Security Officer, twice

- Stalin Prize (1949, 1951)

Soviet Republics

[edit]- Order of the Red Banner of Labour (Armenian SSR)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour (Azerbaijan SSR)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour (Georgian SSR)

- Order of the Red Banner (Georgian SSR)

- Order of the Republic (Tuva)

Mongolia

[edit]- Order of Sukhbaatar (Mongolia)

- Order of the Red Banner (Mongolia)

- Medal "25 Years of the Mongolian People's Revolution" (Mongolia)

In popular culture

[edit]Theatre

[edit]Beria is the central character in Good Night, Uncle Joe by Canadian playwright David Elendune. The play is a fictionalised account of the events leading up to Stalin's death.[109]

Film

[edit]In My Best Friend, General Vasili, Son of Joseph Stalin Beria is portrayed by actor Yan Yanakiev.

Georgian film director Tengiz Abuladze based the character of dictator Varlam Aravidze on Beria in his 1984 film Repentance. Although banned in the Soviet Union for its semi-allegorical critique of Stalinism, it premiered at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival, winning the FIPRESCI Prize, Grand Prize of the Jury, and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury.[110]

Beria was played by British actor Bob Hoskins in the 1991 film Inner Circle, and by David Suchet in Red Monarch.

Simon Russell Beale played Beria in the 2017 satirical film The Death of Stalin.[111]

Television

[edit]In the 1958 CBS production of "The Plot to Kill Stalin" for Playhouse 90, Beria was portrayed by E. G. Marshall. In the 1992 HBO movie Stalin, Roshan Seth was cast as Beria.

In the 1999 film adaptation Animal Farm based on George Orwell's novel, Napoleon's bodyguard Pincher represents Beria.

Beria appears in the third episode ("Superbomb") of the four-part 2007 BBC docudrama series Nuclear Secrets, played by Boris Isarov. In the 2008 BBC documentary series World War II: Behind Closed Doors, Beria was portrayed by Polish actor Krzysztof Dracz.

In the 1969 Doctor Who story The War Games, actor Philip Madoc based the coldly evil War Lord on Beria, even wearing his pince-nez glasses.

Literature

[edit]Alan Williams wrote a spy novel titled The Beria Papers, the plot of which revolves around Beria's alleged secret diaries recording his political and sexual depravities.

At the opening of Kingsley Amis's The Alteration, Beria appears as "Monsignor Laurentius", paired with the similarly black-clad cleric "Monsignor Henricus" (Heinrich Himmler) of the Inquisition.

Beria is a significant character in the alternate history/alien invasion novel series Worldwar by Harry Turtledove, as well as the Axis of Time series by John Birmingham.

In the 1981 novel Noble House by James Clavell, set in 1963 Hong Kong, the main character Ian Dunross receives a set of secret documents regarding a Soviet spy-ring in Hong Kong code-named "Sevrin" signed by an LB (Lavrentiy Beria).

The arrest and execution of Beria is recreated in the Robert Moss novel Moscow Rules as part of the rise of main character Alexander Preobrazensky's father-in-law Marshall Zotov, a character who stands in for Zhukov.

Beria is a significant character in the opening chapters of the 1998 novel Archangel by British novelist Robert Harris.

Beria is a minor character in the 2009 novel The Hundred-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared by Jonas Jonasson.[112]

As "der Kleine Große Mann" ("the Little Big Man"), Beria appears as the abuser of one of the leading characters, Christine, in the 2014 novel Das achte Leben (Für Brilka) (translated as "The Eighth Life (For Brilka)") by Nino Haratischwili.[113]

In the 2015–2017 serialised science fiction novel Unsong by writer Scott Alexander, Beria is mentioned as being in the nicest part of hell, reserved for the worst sinners, along with Hitler and LaLaurie.[114]

A character based on Beria, named "Loria" with his predatorial tendencies, appears in The Saga of Tanya the Evil light novel.[115] Loria is also depicted in the series' animated movie adaptation.[116]

Beria is a significant character in Malcolm Knox's 2024 novel The First Friend, about his fictional childhood friend Vasil Murtov who now works as his driver, and the consequences that follow from a proposed visit by Stalin to Georgia.

Beria is a significant character in Polostan by Neal Stephenson.

See also

[edit]- History of the Soviet Union

- Democracy and Totalitarianism

- Kang Sheng

- Mustapha Tabet, Moroccan police commissioner who raped over 500 women between 1986 and 1993, and was executed by firing squad.

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Beria". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins.

- ^ "Manhattan Project: Espionage and the Manhattan Project, 1940–1945". US Department of Energy – Office of History and Heritage Resources.

- ^ Marlowe 2005, p. 140.

- ^ Malia 2008, p. 1948.

- ^ Curtis 1998, p. xxix.

- ^ Knight 1996, pp. 14–16.

- ^ "Последние Годы Правления Сталина".

- ^ Alliluyeva 1967, p. 138.

- ^ Мікалай Аляксандравіч Зяньковіч; Николай Зенькович (2005). Самые секретные родственники. ОЛМА Медиа Групп. ISBN 978-5-94850-408-7.

- ^ Montefiore 2008, p. 67.

- ^ Zalessky, K.A. "Багиров Мир Джафар Аббасович 1896–1956 Биографический Указатель". Khronos. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ a b Zalessky, K.A. "Берия Лаврентий Павлович 1899–1953 Биографический Указатель". Khronos. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ a b "History's Forgotten People Lavrentiy Beria". Sky History TV. Sky TV. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ Montefiore 2003, pp. 124–125

- ^ Berthold Seewald (10 February 2014). "Ferien mit Stalin: Als Sotschi das Zentrum des Terrors war". Die Welt (in German). Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ Medvedev 1976, pp. 242–3.

- ^ a b Stalin & Kaganovič 2003, p. 182.

- ^ Alliluyeva 1967, p. 15.

- ^ Medvedev 1976.

- ^ Knight 1996, p. 57.

- ^ Wolfe 2001, pp. 420.

- ^ Medvedev 1976, pp. 367–68.

- ^ a b Lakoba 2004, p. 112

- ^ Shenfield 2010

- ^ Rayfield 2012, p. 352

- ^ Kotkin 2017, p. 506

- ^ Hewitt 2013, p. 42

- ^ Kotkin 2017, pp. 506–507

- ^ Blauvelt 2007, pp. 217–218

- ^ Lakoba 2004, pp. 113–114

- ^ Lakoba 2004, p. 117

- ^ Lakoba 2004, p. 118

- ^ Lakoba 2004, p. 119

- ^ Lakoba 2004, pp. 120–121

- ^ Getty & Naumov 1999, pp. 304–05.

- ^ McDermott 1995.

- ^ Beria, L.P. "Записка Л.П. Берии И.В. Сталину о "контрреволюционных" группах в Грузии* 20.07.1937". ЛУБЯНКА: Сталин и Главное управление госбезопасности НКВД. Alexander Yakovlev Foundation. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Medvedev 1976, p. 264.

- ^ Jansen & Petrov 2002, p. 186.

- ^ Shentalinskiĭ 1995, p. 25.

- ^ Slezkine, Yuri (2017). The House of Government, A Saga of the Russian Revolution. Prinveton, N.J.: Princeton U.P. pp. 841–842. ISBN 978-06911-9272-7.

- ^ "Записка Р.А. Руденко в ЦК КПСС о реабилитации А.И. Угарова и С.М. Соболева. 3 января 1956 г." Исторические Материалы. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ Brown 2009, p. 140.

- ^ "Russian parliament condemns Stalin for Katyn massacre". BBC News. 26 November 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ "The Katyn Massacre – Mechanisms of Genocide". Warsaw Institute. 18 May 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Pohl 1999, p. 122.

- ^ "Wisdom of Korea". ysfine.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013.

- ^ Mark O'Neill (17 October 2010). "Kim Il-sung's secret history". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ Knight 1996, p. 143.

- ^ Parrish 1996.

- ^ Knight 1996, p. 151.

- ^ Montefiore 2003, p. 642n.

- ^ Skvortsova, Elena (7 December 2021). "Unknown history. The "Gray Eminence" of the Soviet system Mikhail Suslov". sobesednik. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Top 10 Odd Facts about Stalin". Mix Top Ten. 2 August 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ Rasler, Thompson & Ganguly 2013, p. 39.

- ^ Montefiore 2003, p. 639.

- ^ Montefiore 2003, p. 605.

- ^ Rybin 1996, p. 61.

- ^ Montefiore 2003, pp. 640–644.

- ^ Montefiore 2003, pp. 638–641.

- ^ a b Montefiore 2003, p. 640.

- ^ Montefiore 2003, p. 571.

- ^ a b Montefiore 2003, p. 649.

- ^ a b Montefiore 2003, p. 650.

- ^ Radzinsky 1997.

- ^ Alliluyeva 1967.

- ^ Faria MA (2011). "Stalin's mysterious death". Surg Neurol Int. 2: 161. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.89876. PMC 3228382. PMID 22140646. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012.

- ^ a b Wines, Michael (5 March 2003). "New Study Supports Idea Stalin Was Poisoned". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ Berii͡a 2001, p. 250.

- ^ a b Turner, Matthew D (16 March 2023). "Tyrant's End: Did Joseph Stalin Die From Warfarin Poisoning?". Cureus. 15 (3) e36265. doi:10.7759/cureus.36265. PMC 10105823. PMID 37073203.

- ^ Knight 1996, p. 184.

- ^ Kozlov & Gilburd 2013, p. 111.

- ^ Kozlov & Gilburd 2013, p. 112.

- ^ Hardy 2016, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Kozlov & Gilburd 2013, p. 114.

- ^ Knight 1996, p. 187.

- ^ Knight 1996, p. 190.

- ^ Wydra 2007, p. 165.

- ^ Gaddis 2005.

- ^ Knight 1996, p. 189.

- ^ Loader, Michael (25 November 2016). "Beria and Khrushchev: The Power Struggle over Nationality Policy and the Case of Latvia". Europe-Asia Studies. 68 (10): 1759–1792. doi:10.1080/09668136.2016.1257701. ISSN 0966-8136.

- ^ Andrew & Gordievsky 1990, pp. 423–424.

- ^ Remnick, David. "SOVIETS CHRONICLE DEMISE OF BERIA". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ Cavendish, Richard. "Lavrenti Beria Executed". History Today. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Abe Stein: The Downfall of Beria (July 1953)". marxists.org. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ "CIA On The Beria Purge | PDF". Retrieved 6 May 2024 – via Scribd.

- ^ Rhodes 1995, p. 519.

- ^ Kramer, Mark (1999). "The Early Post-Stalin Succession Struggle and Upheavals in East-Central Europe: Internal-External Linkages in Soviet Policy Making (Part 2)". Journal of Cold War Studies. 1 (2): 3–38. ISSN 1520-3972. JSTOR 26925014.

- ^ Schwartz, Harry (24 December 1953). "Beria Trial Shows Army's Rising Role; BERIA TRIAL SHOWS ARMY'S RISING ROLE". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ "Citizen Kurchatov Stalin's Bomb Maker" (documentary). PBS. Archived from the original on 19 February 2003. Retrieved 12 February 2007.

- ^ Rhodes 1995, p. 523.

- ^ "Лаврентия Берию в 1953 году расстрелял лично советский маршал" (in Russian). 24 June 2010.

- ^ Jansen & Petrov 2002, pp. 186–189.

- ^ "Beria, Lavrenti Pavlovich". WW2 Gravestone. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ Medvedev & Medvedev 2003, p. 86.

- ^ Rayfield, Donald (2005). Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him. New York City: Random House. pp. 466–467. ISBN 978-0-375-75771-6.

- ^ a b Montefiore 2003, p. 506.

- ^ Sudoplatov 1995, p. 97.

- ^ The Soviet Union as Reported by Former Soviet Citizens; Interview Report No.5 (Washington D.C.: United States Department of State, September 1952), p. 4.

- ^ Knight 1996, p. 97.

- ^ a b Montefiore 2003, p. 507.

- ^ a b Montefiore, Simon Sebag (3 June 2010). "Chapter 45". Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar. Orion. ISBN 978-0-297-86385-4.

- ^ Montefiore 2003, p. 508.

- ^ Shepard, Robin (18 January 2003). "Beria's terror files are opened". The Times.

- ^ a b "Grim reminder of Beria terror". The Herald. Glasgow. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ Sixsmith, Martin (2011). Russia: A 1,000-Year Chronicle of the Wild East. Random House. p. 396. ISBN 978-1-4464-1688-4.

- ^ Sixsmith, Martin (2 August 2011). "The Secret Speech/The Scramble For Power". Russia, The Wild East. Season 2. Episode 17. BBC. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "Statesman Lavrenty Pavlovich Beria. Brief biography of Lavrenty Beria". kaskadtuning.ru. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "Good Night Uncle Joe – One Act Version". stageplays.com. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Repentance". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ^ "The Death of Stalin".

- ^ Jonasson 2012.

- ^ Haratischwili 2014.

- ^ Alexander, Scott (22 June 2016). "Interludeי: The Broadcast". unsongbook.com.

- ^ Gaffney, Sean (23 September 2023). "The Saga of Tanya the Evil: Mundus Vult Decipi, Ergo Decipiatur". A Case Suitable for Treatment. Manga Bookshelf. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ "The Saga of Tanya the Evil". TV Tropes. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

Works cited

[edit]- Alliluyeva, Svetlana (1967). Twenty Letters to a Friend. Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-06-010099-5.

- Andrew, Christopher; Gordievsky, Oleg (1990). "11". KGB: The Inside Story (1st ed.). New York: HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 423–424. ISBN 0-06-016605-3.

- Berii͡a, Sergo Lavrentʹevich (2001). Beria, My Father: Inside Stalin's Kremlin. Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-3062-4.

- Blauvelt, Timothy (May 2007), "Abkhazia: Patronage and Power in the Stalin Era", Nationalities Papers, 35 (2): 203–232, doi:10.1080/00905990701254318, S2CID 128803263

- Brown, Archie (2009). The Rise and Fall of Communism. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-113879-9. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- Curtis, Glenn Eldon (1998). Russia: A Country Study. DIANE Publishing Inc. ISBN 978-0-8444-0866-8.

- Gaddis, John Lewis (2005). The Cold War: a new history. New York City: Penguin Press. ISBN 1-59420-062-9.

- Getty, John Arch; Naumov, Oleg V. (1999). The Road to Terror: Stalin and the Self-destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07772-8.

- Haratischwili, Nino (2014). Das achte Leben (Für Brilka). Frankfurter Verlagsanstalt. ISBN 978-3-627-02208-2.

- Hardy, Jeffrey S. (18 October 2016). The Gulag After Stalin: Redefining Punishment in Khrushchev's Soviet Union, 1953–1964. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-0604-2.

- Hewitt, George (2013), Discordant Neighbours: A Reassessment of the Georgian–Abkhazian and Georgian–South Ossetian Conflicts, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-24892-2

- Jansen, Marc; Petrov, Nikita Vasilʹevich (1 April 2002). Stalin's Loyal Executioner: People's Commissar Nikolai Ezhov, 1895-1940. Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-2902-2.

- Jonasson, Jonas (11 September 2012). The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared. Hachette Books. ISBN 978-1-4013-0439-3.

- Kotkin, Stephen (2017). Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941. New York: Random House.

- Knight, Amy (1996). Beria: Stalin's First Lieutenant. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03257-2. OCLC 804864639.

- Kozlov, Denis; Gilburd, Eleonory (2013). The Thaw: Soviet Society and Culture during the 1950s and 1960s. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-1895-4.

- Lakoba, Stanislav (2004), Абхазия после двух империй. XIX–XXI вв. [Abkhazia after two empires: XIX–XXI centuries] (in Russian), Moscow: Materik, ISBN 5-85646-146-0

- Malia, Martin (2008). Soviet Tragedy: A History of Socialism in Russia. Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4391-1854-2.

- Marlowe, Lynn Elizabeth (2005). GED Social Studies. Research and Education Association. ISBN 978-0-7386-0127-4.

- McDermott, K. (1995). "Stalinist Terror in the Comintern: New Perspectives". Journal of Contemporary History. 20 (1): 111–130. doi:10.1177/002200949503000105. JSTOR 260924. S2CID 161318303.

- Medvedev, Roy Aleksandrovich (1976). Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism. Spokesman Books for the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation Limited. ISBN 978-0-85124-150-0.

- Medvedev, Zhores; Medvedev, Roy (2003). The Unknown Stalin. Translated by Dahrendorf, Ellen. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85771-769-6.

- Montefiore, Simon (2003). Stalin: Court of the Red Tsar. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-7678-9.

- Montefiore, Simon (2008). Young Stalin. New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-1-4000-9613-8. OCLC 276996699.

- Parrish, Michael (1996). The Lesser Terror: Soviet State Security, 1939-53: Soviet State Security, 1939-1953. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Pohl, Jonathan Otto (1999). Ethnic Cleansing in the USSR, 1937–1949. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30921-2. OCLC 40158950.

- Radzinsky, Edvard (18 August 1997). Stalin: The First In-depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-385-47954-7.

- Rasler, Karen; Thompson, William R.; Ganguly, Sumit (15 March 2013). How Rivalries End. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0829-0.

- Rayfield, Donald (2012), Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia, London: Reaktion Books, ISBN 978-1-78023-030-6

- Rhodes, Richard (1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-82414-0.

- Rybin, Alekseĭ Trofimovich (1996). Next to Stalin: Notes of a Bodyguard. Northstar Compass Journal.

- Shenfield, Stephen (2010), The Stalin-Beria Terror in Abkhazia, 1936–1953, Sukhum: Abkhaz World, retrieved 8 September 2019

- Shentalinskiĭ, Vitaliĭ (1995). The KGB's Literary Archive. Harvill Press. ISBN 978-1-86046-072-2.

- Stalin, Josif Vissarionovič; Kaganovič, Lazarʹ M. (2003). Davies, R. W.; Khlevniuk, Oleg; Rees, E. A. (eds.). The Stalin - Kaganovich correspondence, 1931-36. Annals of communism. Translated by Shabad, Steven. New Haven, Conn. London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09367-4.

- Sudoplatov, Pavel (1995). Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness – A Soviet Spymaster. Boston: Little Brown & Co. ISBN 0-316-77352-2. OCLC 35547754.

- Wolfe, Bertram David (2001). Three who Made a Revolution: A Biographical History. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8154-1177-2.

- Wydra, Harald (8 February 2007). Communism and the Emergence of Democracy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46218-1.

General references

[edit]- Brent, Jonathan; Naumov, Vladimir Pavlovich (2003). Stalin's Last Crime: The Doctor's Plot. John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5448-3.

- Chang, June; Halliday, Jon (2005). Mao: The Unknown Story. New York: Alfred a Knopf.

- Courtois, Stephane (2010). "Raphael Lemkin and the Question of Genocide under Communist Regimes". In Bieńczyk-Missala, Agnieszka; Dębski, Sławomir (eds.). Rafał Lemkin. PISM. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-83-89607-85-0. LCCN 2012380710.

- Williams, Brian Glyn (2015). Inferno in Chechnya: The Russian-Chechen Wars, the Al Qaeda Myth, and the Boston Marathon Bombings. University Press of New England. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-61168-801-6. LCCN 2015002114.

Further reading

[edit]- Antonov-Ovseenko, Anton (2007). Берия [Beria] (PDF) (in Russian). Sukhumi: Дом печати. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2015.

- Avtorkhanov, Abdurahman (1991). "The Mystery of Stalin's Death". Novyi Mir (in Russian). pp. 194–233.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila (1996). Stalin's Peasants: Resistance and Survival in the Russian Village after Collectivization. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila (1999). Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hastings, Max (2015). The Secret War: Spies, Codes and Guerrillas 1939–1945. London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-750374-2.

- Khruschev, Nikita (1977). Khruschev Remembers: Last Testament. Random House. ISBN 0-517-17547-9.

- Kikodze, Geronti (2003). ქიქოძე, გერონტი, თანამედროვის ჩანაწერები. – [1-ლი გამოც.]. – თბ.: არეტე [Writings of Contemporary Records]. Arete. ISBN 99940-745-6-3. OCLC 59109649..

- Stove, Robert (2003). The Unsleeping Eye: Secret Police and Their Victims. San Francisco: Encounter Books. ISBN 1-893554-66-X. OCLC 470173678.

- Sukhomlinov, Andrey (2004). Кто вы, Лаврентий Берия?: неизвестные страницы уголовного дела (in Russian). Moscow: Detektiv-Press. ISBN 5-89935-060-1. OCLC 62421057.

- Wittlin, Thaddeus (1972). Commissar: The Life and Death of Lavrenty Pavlovich Beria. New York: The Macmillan Co. OCLC 462215687.

- Yakovlev, A.N.; Naumov, V.; Sigachev, Y., eds. (1999). Lavrenty Beria, 1953. Stenographic Report of July's Plenary Meeting of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and Other Documents (in Russian). Moscow: International Democracy Foundation. ISBN 5-89511-006-1.

- Zalessky, Konstantin [in Russian] (2000). Империя Сталина: Биографический энциклопедический словарь (in Russian). Veche. p. 605. ISBN 5-7838-0716-8. OCLC 237410276.

External links

[edit]- Beria, Lavrentiy (1936), The Victory of the National Policy of Lenin and Stalin, Marxists.

- Beria, Lavrentiy (1950), The Great Contrast, Marxists.

- Annotated bibliography for Lavrentiy Beria from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Current Intelligence. The Reversal of the Doctors' Plot and Its Immediate Aftermath, 17 July 1953.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Current Intelligence. Purge of L.P. Beria, 17 April 1954.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Current Intelligence. Summarization of Reports Preceding Beria Purge, 17 August 1954.

- Newspaper clippings about Lavrentiy Beria in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

Lavrentiy Beria

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Revolutionary Beginnings

Childhood and Education in Georgia

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria was born on 29 March 1899 in the village of Merkheuli, located near Sukhumi in Abkhazia, then part of the Kutaisi Governorate within the Russian Empire's Georgian territory.[5] He came from an ethnic Georgian family; his father, Pavel Khukhaevich Beria, worked as a landowner or customs official in the region, while his mother, Marta Ivanovna (née Saakadze), maintained a deeply religious household influenced by Orthodox traditions.[6] Beria's early years were spent in this rural Caucasian setting, marked by the multi-ethnic dynamics of Abkhazia, where Georgian, Abkhaz, and Russian communities coexisted amid the empire's waning influence.[7] Beria received his initial primary education in Sukhumi, attending local schools that provided basic instruction in reading, writing, and arithmetic typical of late imperial Russian provincial systems.[7] These years exposed him to the social upheavals preceding the 1917 revolutions, though records indicate no formal revolutionary involvement during this period; his later claims of early Bolshevik sympathies remain unverified by contemporaneous evidence.[8] By age 16, around 1915, Beria had completed this foundational schooling in Georgia and relocated to Baku in Azerbaijan for advanced technical training, marking the transition from his Georgian childhood roots.[7] [1]Bolshevik Involvement and Early Career

Beria joined the Bolshevik Party in March 1917 while studying engineering at the Baku Polytechnicum.[9] [7] From June to December 1917, he served as a technician for a hydraulic unit on the Romanian front, supporting Bolshevik-aligned military efforts.[9] In mid-1918, during the Turkish occupation of Baku, Beria worked as a clerk at the Caspian Company in White City while conducting underground Bolshevik assignments, which continued through spring 1920 amid shifting control between Ottoman, British, and local forces.[9] By fall 1919, he had infiltrated the counter-intelligence operations of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic's Committee of National Defense, gathering intelligence for Bolshevik revolutionaries.[9] In April 1920, following the Red Army's capture of Baku on April 28, Beria was dispatched by the Caucasian Regional Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) for clandestine operations in Menshevik-controlled Georgia; arrested in Tiflis (Tbilisi), he was released and deported back to Azerbaijan.[9] [7] By August 1920, Beria had risen to managing director of the Central Committee of the Azerbaijan Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and executive secretary of its Extraordinary Commission, roles that positioned him at the intersection of party administration and early security functions.[9] In October 1920, he formally joined the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police, marking his entry into professional counter-revolutionary operations.[7] Between April and May 1921, he advanced rapidly to deputy chief and then head of the Secret Operations Department, followed by appointment as deputy chairman of the Azerbaijan Cheka, where he oversaw suppression of anti-Bolshevik elements in the Caucasus.[9] By November 1922, Beria transferred to Georgia as head of the Secret Operations Division and deputy chairman of the Georgian Cheka, consolidating his early career in regional security apparatus amid the Bolshevik consolidation of Transcaucasia.[9] These positions involved direct participation in intelligence gathering, arrests, and the neutralization of Menshevik and nationalist opposition, establishing Beria's reputation for ruthless efficiency in party enforcement.[1]Rise Within the Transcaucasian Soviet Structure

Leadership in Georgian Affairs

In November 1931, following a purge of the Transcaucasian Communist Party leadership, Lavrentiy Beria was appointed First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic, a position he held until October 1932 and resumed from January 1934 to August 1938.[10][8] This appointment marked his ascent to de facto control over Georgian affairs, building on his prior role as head of the Georgian OGPU since 1926, where he had directed counterintelligence operations.[11] As First Secretary, Beria fused party leadership with security functions, enabling him to enforce Moscow's directives while cultivating a patronage network of loyal obkom secretaries and administrators to solidify his authority.[10][12] Beria's tenure emphasized rapid industrialization and agricultural collectivization aligned with Soviet five-year plans, directing resources toward heavy industry and mechanized farming despite Georgia's agrarian base.[7] Electric power production in Georgia reportedly surged from pre-revolutionary levels, with output increasing significantly by 1935, though such gains were achieved amid forced labor and resource extraction for central Soviet needs.[13] He also pursued limited recognition of Georgian cultural elements, such as promoting the Georgian language in official use, to mitigate nationalist resistance and legitimize Soviet rule locally, contrasting with stricter Russification elsewhere.[14] These measures facilitated Georgia's tighter integration into the Transcaucasian SFSR and broader USSR, with Beria reporting directly to Joseph Stalin on regional compliance.[15] Administrative reforms under Beria reorganized local soviets and economic councils to prioritize central planning, including the expansion of mining and hydroelectric projects in the Caucasus.[7] By 1938, his control extended to key appointments across Georgia's oblasts, ensuring policy execution but also centralizing power in Tbilisi under his allies, which positioned him for elevation to Moscow.[10] This era laid the groundwork for Georgia's contribution to Soviet wartime mobilization, though at the cost of internal stability.[2]Elimination of Regional Opponents

Beria played a central role in quelling the August Uprising of 1924, a widespread anti-Soviet rebellion in Georgia that sought to restore independence from Bolshevik rule, personally overseeing operations as a senior Cheka officer that led to the execution of up to 10,000 participants and sympathizers.[16] [17] This repression not only crushed immediate resistance from Menshevik nationalists and former Democratic Republic of Georgia officials but also eliminated potential bases for future regional autonomy, solidifying Soviet control in the Caucasus.[18] Within the Georgian Bolshevik apparatus, Beria systematically targeted intra-party rivals to consolidate his authority, beginning in the mid-1920s as he ascended through the OGPU ranks. By the early 1930s, as First Secretary of the Transcaucasian Regional Committee, he launched accusations of "national deviationism" against established Georgian communists, including attacks on Gaioz Devdariani, the Minister of Education, whose brothers George and Shalva were executed on Beria's orders as part of fabricated treason cases.[19] These actions reflected Beria's strategy of framing local leaders as ideologically unreliable to preempt challenges to his growing influence under Stalin's patronage. A pivotal instrument in this elimination was Beria's 1935 treatise On the History of Bolshevik Organizations in Transcaucasia, presented as a report to Tiflis party activists, which retroactively condemned pre-revolutionary and early Soviet regional figures as deviationists for insufficient loyalty to Stalin, thereby justifying their purge and rewriting Transcaucasian Bolshevik history to elevate Stalin's centrality.[20] This historiographical assault facilitated the removal of dozens of veteran Transcaucasian party members, including those associated with earlier factions like the "Old Bolsheviks" in Georgia and Armenia, through arrests, show trials, and executions orchestrated via Beria's control of local security organs.[21] Regional autonomy figures faced similar fates; for instance, Abkhazian Soviet leader Nestor Lakoba, who maintained semi-independent influence, died under suspicious circumstances in December 1936 shortly after dining with Beria, with contemporary accounts and later analyses attributing the death to poisoning as a means to neutralize a non-Georgian ethnic rival in the Transcaucasian hierarchy.[22] Such targeted eliminations extended to Armenian and Azerbaijani opponents, ensuring Beria's unchallenged dominance in the federation by 1937, though they prefigured the broader Great Purge's intensity in the region.[23]Integration into Stalin's Central Apparatus

Personal Ties to Stalin

Lavrentiy Beria's relationship with Joseph Stalin developed through shared Georgian origins and Beria's demonstrated loyalty in regional Soviet administration. Born in 1899 in the Mingrelian region of Georgia, Beria advanced in the Transcaucasian Communist Party apparatus during the 1920s and 1930s, aligning closely with Stalin's centralizing policies against local rivals. By 1931, Beria had become party secretary in Georgia, where he orchestrated purges that solidified Stalinist control, earning Stalin's favor as an effective enforcer.[24][25] Stalin's frequent vacations in Georgia provided opportunities for direct interaction, fostering personal rapport built on ethnic affinity and mutual political utility. Beria cultivated these ties by hosting Stalin and ensuring unwavering obedience, which contrasted with the purges of other Caucasian leaders. This proximity extended to Stalin's inner circle; photographs depict Beria interacting familiarly with Stalin's daughter Svetlana, indicating access beyond mere professional subordination. Stalin's preference for Georgian associates, including shared cultural elements like regional wines and cuisine, reinforced this bond.[24][26] In 1938, Stalin summoned Beria to Moscow as deputy head of the NKVD, promoting him to chief within months after executing his predecessor Nikolai Yezhov amid the Great Purge. This elevation reflected Stalin's trust in Beria's ruthlessness and administrative acumen, positioning him as a key instrument for central terror operations. Beria maintained this allegiance through the 1940s, overseeing security during World War II and atomic projects, though their dynamic involved Stalin's characteristic paranoia, with Beria navigating purges of subordinates while avoiding personal downfall until after Stalin's death in 1953.[2][4]Appointment to Key Security Positions

In August 1938, amid the height of the Great Purge, Joseph Stalin summoned Lavrentiy Beria from his position in the Transcaucasus to Moscow, appointing him First Deputy People's Commissar of Internal Affairs on August 22, effectively as deputy to Nikolai Yezhov, the incumbent head of the NKVD.[7][11] This rapid elevation reflected Stalin's dissatisfaction with Yezhov's management of the purges, which had spiraled into widespread chaos, and Beria's reputation for ruthless efficiency in suppressing opposition in Georgia.[2] Within days of his appointment, on August 29, 1938, Beria assumed control of the NKVD's Main Directorate of State Security (GUGB), the branch responsible for political repression and intelligence, consolidating his influence over core security operations.[7][11] By November 1938, following Yezhov's arrest on November 10 and subsequent dismissal, Beria was elevated to full People's Commissar of Internal Affairs, heading the entire NKVD apparatus until 1946.[11][2] This transition marked a shift in the purges' direction, with Beria tasked by Stalin to both complete the elimination of perceived enemies and rein in the unchecked terror that had implicated even loyal Bolsheviks. Beria's ascent included installing trusted subordinates from the Caucasus, such as Vladimir Dekanozov as deputy commissar, which strengthened his personal network within the security services and ensured alignment with Stalin's directives.[7] These appointments centralized power in Moscow's security apparatus under Beria's command, enabling more targeted repressions while purging Yezhov's appointees, thereby solidifying his role as a key instrument of Stalin's control.[2]Command of the NKVD (1938–1946)

Orchestration of the Great Purge

Lavrentiy Beria was transferred to Moscow from his position in the Transcaucasus and appointed as First Deputy People's Commissar of Internal Affairs on 22 August 1938, serving under Nikolai Yezhov, the architect of the ongoing Great Purge.[27] In this role, Beria began consolidating influence within the NKVD apparatus amid the escalating repressions that had already claimed an estimated 681,692 lives through executions alone by the end of 1938.[28] On 23 November 1938, Yezhov was dismissed, and Beria assumed full leadership as People's Commissar of Internal Affairs, officially taking command of the NKVD on that date.[29] Under Beria's direction, the NKVD shifted focus to purging its own ranks, arresting over 7,000 officers and executing key figures from Yezhov's era, including Yezhov himself, who was tried and shot on 4 February 1940.[25] This internal "purge of the purgers" helped curtail the mass operations of the Great Terror, reducing the annual execution quotas from peaks exceeding 300,000 in 1937–1938 to fewer than 2,600 by 1939, though selective repressions persisted against alleged Trotskyists, foreign spies, and party dissidents.[25] Beria's oversight included reviewing and revising thousands of cases from the Purge era; between late 1938 and 1940, approximately 330,000 prisoners were released from camps and prisons, with many rehabilitated posthumously to signal a moderation in terror tactics.[30] However, he maintained Stalin's apparatus of control by fabricating dossiers and signing off on troika decisions for executions, such as the 1939 liquidation of remaining Old Bolsheviks and military figures accused of conspiracy.[31] Archival evidence indicates Beria personally approved death sentences for at least 15,000 individuals in 1939–1941, ensuring the NKVD's role in suppressing perceived internal threats while transitioning from indiscriminate mass arrests to more targeted operations.[32] This phase under Beria marked the formal conclusion of the Great Purge's zenith, as Politburo directives in December 1938 halted widespread "enemy" hunts, yet his administration expanded the Gulag system, with prisoner numbers reaching over 2 million by 1941, reflecting a sustained repressive framework rather than outright cessation of coercion.[21] Beria's strategic repositioning distanced the NKVD from Yezhov's excesses, attributing blame to his predecessor in internal reports, which facilitated Beria's entrenchment as Stalin's primary security enforcer.[33]World War II Security Operations and Atrocities