Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Logical biconditional

View on WikipediaThis article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2013) |

| Logical connectives | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related concepts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Applications | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(true part in red)

In logic and mathematics, the logical biconditional, also known as material biconditional or equivalence or bidirectional implication or biimplication or bientailment, is the logical connective used to conjoin two statements and to form the statement " if and only if " (often abbreviated as " iff "[1]), where is known as the antecedent, and the consequent.[2][3]

Nowadays, notations to represent equivalence include .

is logically equivalent to both and , and the XNOR (exclusive NOR) Boolean operator, which means "both or neither".

Semantically, the only case where a logical biconditional is different from a material conditional is the case where the hypothesis (antecedent) is false but the conclusion (consequent) is true. In this case, the result is true for the conditional, but false for the biconditional.[2]

In the conceptual interpretation, P = Q means "All P's are Q's and all Q's are P's". In other words, the sets P and Q coincide: they are identical. However, this does not mean that P and Q need to have the same meaning (e.g., P could be "equiangular trilateral" and Q could be "equilateral triangle"). When phrased as a sentence, the antecedent is the subject and the consequent is the predicate of a universal affirmative proposition (e.g., in the phrase "all men are mortal", "men" is the subject and "mortal" is the predicate).

In the propositional interpretation, means that P implies Q and Q implies P; in other words, the propositions are logically equivalent, in the sense that both are either jointly true or jointly false. Again, this does not mean that they need to have the same meaning, as P could be "the triangle ABC has two equal sides" and Q could be "the triangle ABC has two equal angles". In general, the antecedent is the premise, or the cause, and the consequent is the consequence. When an implication is translated by a hypothetical (or conditional) judgment, the antecedent is called the hypothesis (or the condition) and the consequent is called the thesis.

A common way of demonstrating a biconditional of the form is to demonstrate that and separately (due to its equivalence to the conjunction of the two converse conditionals[2]). Yet another way of demonstrating the same biconditional is by demonstrating that and .

When both members of the biconditional are propositions, it can be separated into two conditionals, of which one is called a theorem and the other its reciprocal.[citation needed] Thus whenever a theorem and its reciprocal are true, we have a biconditional. A simple theorem gives rise to an implication, whose antecedent is the hypothesis and whose consequent is the thesis of the theorem.

It is often said that the hypothesis is the sufficient condition of the thesis, and that the thesis is the necessary condition of the hypothesis. That is, it is sufficient that the hypothesis be true for the thesis to be true, while it is necessary that the thesis be true if the hypothesis were true. When a theorem and its reciprocal are true, its hypothesis is said to be the necessary and sufficient condition of the thesis. That is, the hypothesis is both the cause and the consequence of the thesis at the same time.

Notations

[edit]Notations to represent equivalence used in history include:

- in George Boole in 1847.[4] Although Boole used mainly on classes, he also considered the case that are propositions in , and at the time is equivalence.

- in Frege in 1879;[5]

- in Bernays in 1918;[6]

- in Hilbert in 1927 (while he used as the main symbol in the article);[7]

- in Hilbert and Ackermann in 1928[8] (they also introduced while they use as the main symbol in the whole book; is adopted by many followers such as Becker in 1933[9]);

- (prefix) in Łukasiewicz in 1929[10] and (prefix) in Łukasiewicz in 1951;[11]

- in Heyting in 1930;[12]

- in Bourbaki in 1954;[13]

- in Chazal in 1996;[14]

and so on. Somebody else also use or occasionally.[citation needed][vague][clarification needed]

Definition

[edit]Logical equality (also known as biconditional) is an operation on two logical values, typically the values of two propositions, that produces a value of true if and only if both operands are false or both operands are true.[2]

Truth table

[edit]The following is a truth table for :

| F | F | T |

| F | T | F |

| T | F | F |

| T | T | T |

When more than two statements are involved, combining them with might be ambiguous. For example, the statement

may be interpreted as

- ,

or may be interpreted as saying that all xi are jointly true or jointly false:

As it turns out, these two statements are only the same when zero or two arguments are involved. In fact, the following truth tables only show the same bit pattern in the line with no argument and in the lines with two arguments:

meant as equivalent to

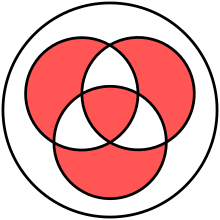

The central Venn diagram below,

and line (ABC ) in this matrix

represent the same operation.

meant as shorthand for

The Venn diagram directly below,

and line (ABC ) in this matrix

represent the same operation.

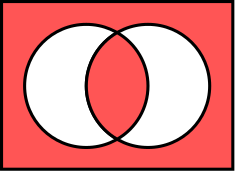

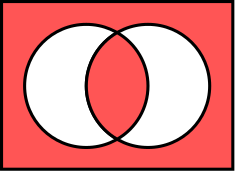

The left Venn diagram below, and the lines (AB ) in these matrices represent the same operation.

Venn diagrams

[edit]Red areas stand for true (as in ![]() for and).

for and).

|

|

|

Properties

[edit]Commutativity: Yes

Associativity: Yes

|

|

|

|

|

Distributivity: Biconditional doesn't distribute over any binary function (not even itself), but logical disjunction distributes over biconditional.

Idempotency: No

Monotonicity: No

|

|

|

|

Truth-preserving: Yes

When all inputs are true, the output is true.

Falsehood-preserving: No

When all inputs are false, the output is not false.

Walsh spectrum: (2,0,0,2)

Nonlinearity: 0 (the function is linear)

Rules of inference

[edit]Like all connectives in first-order logic, the biconditional has rules of inference that govern its use in formal proofs.

Biconditional introduction

[edit]Biconditional introduction allows one to infer that if B follows from A and A follows from B, then A if and only if B.

For example, from the statements "if I'm breathing, then I'm alive" and "if I'm alive, then I'm breathing", it can be inferred that "I'm breathing if and only if I'm alive" or equivalently, "I'm alive if and only if I'm breathing." Or more schematically:

B → A A → B ∴ A ↔ B

B → A A → B ∴ B ↔ A

Biconditional elimination

[edit]Biconditional elimination allows one to infer a conditional from a biconditional: if A ↔ B is true, then one may infer either A → B, or B → A.

For example, if it is true that I'm breathing if and only if I'm alive, then it's true that if I'm breathing, then I'm alive; likewise, it's true that if I'm alive, then I'm breathing. Or more schematically:

A ↔ B ∴ A → B

A ↔ B ∴ B → A

Colloquial usage

[edit]One unambiguous way of stating a biconditional in plain English is to adopt the form "b if a and a if b"—if the standard form "a if and only if b" is not used. Slightly more formally, one could also say that "b implies a and a implies b", or "a is necessary and sufficient for b". The plain English "if'" may sometimes be used as a biconditional (especially in the context of a mathematical definition[15]). In which case, one must take into consideration the surrounding context when interpreting these words.

For example, the statement "I'll buy you a new wallet if you need one" may be interpreted as a biconditional, since the speaker doesn't intend a valid outcome to be buying the wallet whether or not the wallet is needed (as in a conditional). However, "it is cloudy if it is raining" is generally not meant as a biconditional, since it can still be cloudy even if it is not raining.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Iff". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- ^ a b c d Peil, Timothy. "Conditionals and Biconditionals". web.mnstate.edu. Archived from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2019-11-25.

- ^ Brennan, Joseph G. (1961). Handbook of Logic (2nd ed.). Harper & Row. p. 81.

- ^ Boole, G. (1847). The Mathematical Analysis of Logic, Being an Essay Towards a Calculus of Deductive Reasoning. Cambridge/London: Macmillan, Barclay, & Macmillan/George Bell. p. 17.

- ^ Frege, G. (1879). Begriffsschrift, eine der arithmetischen nachgebildete Formelsprache des reinen Denkens (in German). Halle a/S.: Verlag von Louis Nebert. p. 15.

- ^ Bernays, P. (1918). Beiträge zur axiomatischen Behandlung des Logik-Kalküls. Göttingen: Universität Göttingen. p. 3.

- ^ Hilbert, D. (1928) [1927]. "Die Grundlagen der Mathematik". Abhandlungen aus dem mathematischen Seminar der Hamburgischen Universität (in German). 6: 65–85. doi:10.1007/BF02940602.

- ^ Hilbert, D.; Ackermann, W. (1928). Grundzügen der theoretischen Logik (in German) (1 ed.). Berlin: Verlag von Julius Springer. p. 4.

- ^ Becker, A. (1933). Die Aristotelische Theorie der Möglichkeitsschlösse: Eine logisch-philologische Untersuchung der Kapitel 13-22 von Aristoteles' Analytica priora I (in German). Berlin: Junker und Dünnhaupt Verlag. p. 4.

- ^ Łukasiewicz, J. (1958) [1929]. Słupecki, J. (ed.). Elementy logiki matematycznej (in Polish) (2 ed.). Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- ^ Łukasiewicz, J. (1957) [1951]. Słupecki, J. (ed.). Aristotle's Syllogistic from the Standpoint of Modern Formal Logic (in Polish) (2 ed.). Glasgow, New York, Toronto, Melbourne, Wellington, Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, Karachi, Lahore, Dacca, Cape Town, Salisbury, Nairobi, Ibadan, Accra, Kuala Lumpur and Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Heyting, A. (1930). "Die formalen Regeln der intuitionistischen Logik". Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Physikalisch-mathematische Klasse (in German): 42–56.

- ^ Bourbaki, N. (1954). Théorie des ensembles (in French). Paris: Hermann & Cie, Éditeurs. p. 32.

- ^ Chazal, G. (1996). Eléments de logique formelle. Paris: Hermes Science Publications.

- ^ In fact, such is the style adopted by Wikipedia's manual of style in mathematics.

External links

[edit] Media related to Logical biconditional at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Logical biconditional at Wikimedia Commons

This article incorporates material from Biconditional on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

Logical biconditional

View on Grokipedia| p | q | p ↔ q |

|---|---|---|

| True | True | True |

| True | False | False |

| False | True | False |

| False | False | True |

Fundamentals

Definition

The logical biconditional, denoted as , is a binary connective in propositional logic that links two propositions and , asserting their logical equivalence. It evaluates to true precisely when and share the same truth value—either both true or both false—and false otherwise.[8] This connective originates from the natural language expression "if and only if" (often abbreviated as IFF), which conveys mutual implication between statements. The formalization of logical relations in modern symbolic logic, enabling the expression of equivalences through primitive connectives such as implication and negation, was advanced by Gottlob Frege in his seminal 1879 work Begriffsschrift.[9] Syntactically, the biconditional functions as a propositional connective in constructing well-formed formulas, adhering to standard binding precedence rules where it ranks lowest, on par with material implication, thus necessitating parentheses to clarify scope in compound expressions.[10] For example, the proposition "It rains if and only if the ground is wet" employs the biconditional to indicate that rain implies wet ground and vice versa, capturing the bidirectional dependency.[11]Notations

The logical biconditional is commonly denoted by the symbol ↔ (Unicode U+2194, left right arrow) or ⇔ (Unicode U+21D4, left right double arrow) in propositional logic texts and formal semantics.[12] In mathematical writing using LaTeX, the command \iff produces a double arrow symbol equivalent to ⇔, widely adopted for expressing "if and only if" relations in proofs and definitions.[13] Alternative notations appear in specialized logical systems. In algebraic logics and Boolean algebra, the triple bar ≡ is used to indicate logical equivalence between propositions p and q, written as p ≡ q, emphasizing the structural identity of their truth values.[14] In Polish notation, developed by Jan Łukasiewicz, the biconditional is represented in prefix form as E p q, where E stands for equivalence, avoiding parentheses by placing the operator before its operands.[15] Programming languages often adapt these concepts with operators that handle equality for boolean values, effectively implementing the biconditional. In Python, the == operator compares booleans for equality, yielding true only if both are true or both are false, though it is primarily an equality check rather than a dedicated logical connective.[16] Similarly, in MySQL, the <=> operator provides NULL-safe equality, which for boolean-like comparisons functions as a biconditional by returning true when values match exactly, including handling of NULLs as a form of equivalence.[17] Historically, before standardized symbols, the biconditional was expressed verbally as "if and only if" in pre-symbolic logic texts. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, in his 17th-century writings on logic, employed such verbal forms alongside early algebraic notations like "=" to denote identity and equivalence between concepts, laying groundwork for later symbolic developments. The arrow symbols ↔ and ⇔ emerged in the early 20th century, popularized in works by logicians such as David Hilbert and Bertrand Russell.[18][19]Representations

Truth Table

The truth table for the logical biconditional exhaustively lists all possible truth value assignments for the propositions and , showing the resulting truth value of the biconditional.[4]| T | T | T |

| T | F | F |

| F | T | F |

| F | F | T |

Venn Diagrams

Venn diagrams provide a visual representation of the logical biconditional by treating the propositions and as sets within a universe of possible truth value combinations. The diagram consists of two overlapping circles, one representing the set where is true and the other where is true, dividing the plane into four regions corresponding to the pairs (true, true), (true, false), (false, true), and (false, false). The biconditional holds where both propositions share the same truth value, shading the regions for both true (the intersection) and both false (the area outside both circles), while leaving the mixed regions unshaded.[22] This construction highlights the biconditional as the union of the intersection of the sets and the intersection of their complements: . These shaded areas align with the truth conditions of the biconditional, which is true precisely when and are equivalent in truth value.[22] In predicate logic, the biconditional extends to statements like , interpreted as the truth sets of predicates and being identical, meaning the domains where the properties coincide completely. This set equality can be visualized similarly, with Venn diagrams showing total overlap or equivalence across the universe.[23] Venn diagrams are most effective for illustrating the biconditional in simple binary propositional cases but become less intuitive for complex formulas involving multiple connectives, where truth tables offer a more exhaustive and precise enumeration.[24]Properties

Algebraic Properties

The logical biconditional satisfies several key algebraic properties within the framework of Boolean algebra, reflecting its role as a binary operation that captures equivalence between propositions. These properties facilitate simplification and manipulation of logical expressions involving the biconditional. The biconditional is commutative, meaning . This follows directly from the symmetry in the truth table for the biconditional, where the output depends only on whether and have matching truth values, regardless of order.[25] A brief proof sketch using substitution leverages the definition : since implication is not commutative but the conjunction of and swaps symmetrically, the overall equivalence holds.[26] It is also associative: . This property arises because the biconditional models transitive equivalence; chaining equivalences preserves the relation across groupings. Verification via truth table confirms identical columns for both sides across all 8 combinations of truth values for .[27] An alternative sketch substitutes the definition repeatedly: expanding both sides yields equivalent disjunctions of matching conjunctions, such as , balancing to tautological identity. The operation is idempotent: , where denotes the tautology (always true). By definition, and always share the same truth value, making the biconditional true in all cases; the truth table has a single column of T for both input combinations (T or F).[28] This contrasts with non-idempotent connectives like exclusive or, underscoring the biconditional's equivalence nature. Other notable laws include absorption-like identities specific to the biconditional. For instance, . This holds because the left side requires to match : when is false, both are false (true); when is true, is true only if is (equivalent to ). A detailed sketch: . The second conjunct simplifies to (since implies ); the first is .[28]| Property | Formula | Brief Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Commutativity | Symmetric truth table columns. | |

| Associativity | Transitivity of equivalence; truth table match. | |

| Idempotence | Identical inputs always match. | |

| Absorption example | Simplifies to implication via identity conjunct. |

Equivalences to Other Connectives

The logical biconditional is not a primitive connective in propositional logic and can be decomposed into expressions using simpler connectives such as implication, conjunction, disjunction, and negation. A core equivalence defines it as the conjunction of mutual implications: . This formulation captures the biconditional's semantics, where both propositions must imply each other for the statement to hold true.[14] Alternative decompositions emphasize different aspects of the biconditional's truth conditions. For instance, it is equivalent to the disjunction of the cases where both propositions are true or both are false: . This form directly reflects the truth table, being true precisely when and share the same truth value. Similarly, the biconditional corresponds to the negation of the exclusive disjunction (XOR): , underscoring its role as the "equivalence" operator in contrast to the "inequivalence" of XOR.[29] The biconditional can also be constructed using solely the Sheffer stroke, denoted as NAND (), which serves as a single primitive capable of expressing all Boolean connectives. Since the singleton set {NAND} is functionally complete—meaning any Boolean function, including the biconditional, can be realized through compositions of NAND operations—the biconditional is composite rather than primitive in this basis. For example, basic connectives like negation (), conjunction (), and disjunction () are first derived, allowing subsequent construction of the biconditional via the equivalences above. This universality of NAND highlights the biconditional's derivability in minimal connective sets.[30][31] Historically, in Hilbert-style axiomatic systems for propositional logic, efforts to minimize primitive connectives led to defining the biconditional in terms of implication () and negation () alone, rather than treating it as primitive. Standard Hilbert systems use axioms based on implication and negation, with the biconditional introduced as an abbreviation , where conjunction itself is defined using the primitives (e.g., ). This reduction supports the formal economy of such systems while preserving expressive power.[32]Inference Rules

Biconditional Introduction

In natural deduction systems for propositional and predicate logic, the biconditional introduction rule, commonly denoted as ↔I, permits the derivation of a biconditional from the premises and .[33] This rule captures the logical equivalence between two propositions by establishing mutual implication.[34] The application of ↔I requires the construction of two separate subproofs within a Fitch-style natural deduction framework. In the first subproof, assume and derive , thereby establishing via the implication introduction rule (→I). In the second subproof, assume and derive , yielding via →I. The biconditional is then inferred by discharging both assumptions and applying ↔I to the conclusions of these subproofs.[33][35] As a simplified example, consider proving the commutativity of conjunction: . In the first subproof, assume , derive and using conjunction elimination (∧E), then derive using conjunction introduction (∧I), establishing . In the second subproof, assume , derive similarly, yielding . Applying ↔I then confirms the biconditional equivalence between the two formulations. The justification for ↔I lies in its preservation of truth: if both implications are true, the biconditional must hold, as the propositions are true under exactly the same conditions.[34] In sequent calculus, the rule takes a schematic form where, from sequents and , one infers , reflecting the right introduction rule for the biconditional.[36] This formulation ensures soundness in classical proof systems. Variations in presentation occur across deduction systems; for instance, Fitch-style natural deduction uses nested subproof boxes to manage assumptions, while sequent calculus employs linear sequent notations without explicit subproofs, focusing instead on antecedent and succedent partitions.[33][35]Biconditional Elimination

In natural deduction systems for propositional logic, the biconditional elimination rule (denoted ↔E) permits the derivation of two conditional statements from a given biconditional. Specifically, from the premise , one infers both and , often presented as a single rule yielding both implications or in two separate applications.[37] This rule facilitates proof construction by decomposing an equivalence into unidirectional implications, enabling the application of other inference rules like modus ponens to advance the argument without requiring verification of the reverse direction. For example, given the biconditional "a triangle is equilateral if and only if all its sides are equal," biconditional elimination yields the implication "if all sides of a triangle are equal, then it is equilateral," which can then be invoked in geometric demonstrations.[37] The rule imposes no side effects on surrounding assumptions or subproofs; it merely extends the proof by adding the implications based on the biconditional line, preserving the structure of any nested scopes. In intuitionistic logic, where the biconditional is defined as , the elimination remains valid via conjunction elimination and is invertible, allowing the biconditional to be reconstructed through conjunction introduction without loss of information.[38] In contrast to equational reasoning systems, where equivalence (often denoted =) supports direct substitution of terms in expressions, biconditional elimination in sentential logic yields implications that necessitate additional steps—such as assumption introduction—for effective replacement within larger formulas.[34]Applications

Formal Usage in Mathematics and Logic

In mathematics, the logical biconditional is fundamental for expressing definitions where one property is both necessary and sufficient for another. For instance, a natural number is even if and only if it is divisible by 2, denoted is even is divisible by 2, ensuring the conditions are equivalent and hold simultaneously or not at all.[39] This usage captures the bidirectional implication, where each side guarantees the truth of the other, as formalized by meaning .[40] Extending to predicate logic, the biconditional defines equivalence between predicates over a domain. The statement asserts definitional equivalence, meaning the predicates and identify precisely the same elements in the universe, with no distinctions between them.[41] In proof theory, biconditionals play a key role in formal systems, where Gödel's completeness theorem for first-order logic guarantees that any semantically valid formula, including those with biconditionals, is syntactically provable from the axioms.[42] This ensures equivalence relations expressed via biconditionals can be rigorously established. In automated theorem proving, biconditional definitions enable completeness results, allowing systems to unfold recursive or non-recursive definitions efficiently to verify equivalences.[43] In set theory, set equality is defined using the biconditional via the Axiom of Extensionality: two sets and are equal, , if and only if , meaning they share exactly the same members.[44] This biconditional formulation underscores that sets are determined solely by their elements, with proofs of equality requiring demonstration of mutual subset inclusion, equivalent to the bidirectional membership condition.[45] Similarly, via characteristic functions, sets and are equal if their characteristic functions satisfy for all , which corresponds to pointwise logical equivalence under the biconditional.[46] In modern computer science applications, the biconditional manifests in circuit design through the XNOR gate, which implements logical equivalence by outputting true only when inputs are identical, directly modeling .[47] This gate is essential for comparators and parity checks in digital systems. In database queries, equi-joins in SQL rely on equality conditions, such asON A.key = B.key, to combine rows where values match exactly, effectively applying a biconditional filter for equivalence between attributes.[48]

Colloquial and Everyday Usage

In everyday language, the phrase "if and only if" is frequently employed in contracts, laws, and instructions to denote strict equivalence between conditions and outcomes, ensuring clarity in obligations. For instance, a contract might stipulate that payment is due if and only if the goods are delivered in full compliance with specifications, preventing disputes over partial fulfillment.[49] Similarly, legal statutes or instructional guidelines, such as "You pass the course if and only if you achieve at least 70% on the final exam," use this phrasing to establish necessary and sufficient criteria without ambiguity.[50] However, colloquial usage often leads to misinterpretations, where speakers confuse the biconditional with one-directional implication ("if"), resulting in logical fallacies during arguments or decision-making. Everyday statements like "I'll go to the party if my friend goes" are typically intended as biconditionals—meaning attendance occurs if and only if the friend attends—but listeners or speakers may treat them as mere implications, overlooking the necessity aspect and leading to mismatched expectations.[50] This confusion can escalate in debates, where assuming a one-way condition undermines the equivalence, fostering errors in causal reasoning. In rhetorical contexts, "if and only if" strengthens assertions by emphasizing both necessity and sufficiency, as in claims like "A policy succeeds if and only if it addresses core stakeholder needs," which underscores an unbreakable link to bolster persuasive impact.[50] Such phrasing appears in political discourse to frame ideals rigidly, implying failure without the specified condition. Cultural proverbs and idioms also reflect biconditional thinking, implying strict reciprocity. Psychologically, humans intuitively recognize biconditional structures but frequently overlook their full implications in reasoning tasks, as demonstrated by the Wason selection task. In this experiment, participants struggle to identify cards that falsify conditional rules, often due to interpreting them as biconditionals rather than testing both directions, revealing limitations in everyday logical application.[51] This highlights how biconditionals are grasped conceptually but misapplied under cognitive load.References

- https://proofwiki.org/wiki/Biconditional_is_Commutative

- https://proofwiki.org/wiki/Biconditional_is_Associative