Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

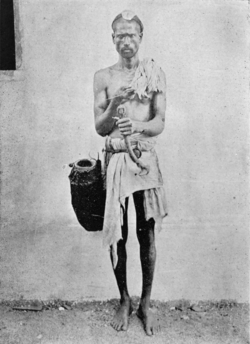

Billava

View on Wikipedia

The Billava (IPA: [bilːɐʋɐ]), Billoru,[1] Biruveru[2] people are an ethnic tuluva group of India. They constitute 18% of the coastal Karnataka population.[3][4] They are found traditionally in Tulu Nadu region and primarily engaged in toddy tapping, cultivation and other activities. They have used both missionary education and Sri Narayana Guru's reform movement to upgrade themselves.

Key Information

Etymology and origins

[edit]The Billavas are first recorded in inscriptions dating from the fifteenth century AD but Amitav Ghosh notes that "... this is merely an indication of their lack of social power; there is every reason to suppose that all the major Tuluva castes share an equally long history of settlement in the region". The earliest epigraphy for the Tuluva Bunt community dates to around 400 years earlier.[5]

L. K. Ananthakrishna Iyer recounted the community's belief that billava means bowmen and that it "applied to the castemen who were largely employed as soldiers by the native rulers of the district".[1] Edgar Thurston had reached a similar conclusion in 1909.[6][a]

Language

[edit]

There is a complex linguistic environment in Tulu Nadu, which is the area of India to which the Billavas trace their origin. A compact geographic area, Tulu Nadu lies on the coastal belt of Karnataka and Kerala and has natural boundaries in the form of the Arabian Sea, the hills of the Western Ghats and the rivers Suvarna and Chandragiri. It includes the South Canara district of Karnataka and the Kasaragod area of Kerala, which were formerly united for administrative purposes within the Madras Presidency. Although many languages and dialects are traditionally to be found there—for example, Tulu, Kannada, Konkani and Marathi—it is the first two of these that are common throughout,[7] and of those two it is Tulu that gave rise to the region's name.[8]

Traditionally, Kannada is used in formal situations such as education, while Tulu is the lingua franca used in everyday communication. Tulu is more accepted as the primary language in the north of the Tulu Nadu region, with the areas south of the Netravati river demonstrating a more traditional, although gradually diminishing, distinction between that language and the situations in which Kannada is to be preferred. A form of the Tulu language known as Common Tulu has been identified, and this is spreading as an accepted standard for formal communication. Although four versions of it exist, based on geographic demarcations and also the concentration of various caste groups within those areas, that version which is more precisely known as Northern Common Tulu is superseding the other three dialects. As of 1998[update] the Brahmin community use Common Tulu only to speak with those outside their own caste, while communities such as the Bunts, Billavas and Gouds use it frequently, and the tribal communities are increasingly abandoning their own dialects in favour of it.[7]

William Logan's work Manual of Malabar, a publication of the British Raj period, recognised the Billavas as being the largest single community in South Canara, representing nearly 20 per cent of that district's population.[9]

Marriage, death and inheritance

[edit]The Billavas practised the matrilineal system of inheritance known as Aliya Kattu[10] or Aliya Santana. Ghosh describes that this system entailed that "men transmit their immovable property, not to their own children, but matrilineally, to their sister's children."[11]

Iyer described the rules regarding marriage as

A Billava does not marry his sister's daughter or mother's sister's daughter. He can marry his paternal aunt's or maternal uncle's daughter. Two sisters can be taken in marriage simultaneously or at different times. Two brothers can marry two sisters.[1]

Marriage of widows was permitted but the wedding ritual in such cases was simplified. An amended version of the ceremony was also used for situations where an illegitimate child might otherwise result: the father had to marry the pregnant woman in such circumstances.[12]

Women were considered to be ritually polluted at the time of their first menstrual cycle and also during the period of pregnancy and childbirth.[10]

The Billava dead are usually cremated, although burial occurs in some places, and there is a ritual pollution period observed at this time also.[13] The Billava community is one of a few in India that practice posthumous marriage. Others that do so include the Badagas, Komatis and the Todas.[14]

Subgroups

[edit]All of the Tuluva castes who participate fully in Bhuta worship also have loose family groupings known as balis. These groups are also referred to as "septs", and are similar to the Brahmin gotras except that their membership is based on matrilineal rather than patrilineal descent.[11] Iyer noted 16 balis within the Billava community and that some of these had further subdivisions.[1] Thurston said of these exogamous Billava groups that "There is a popular belief that these are sub-divisions of the twenty balis which ought to exist according to the Aliya Santana system (inheritance of the female line)."[15]

Worship of Bhutas

[edit]

The Billavas were among the many communities to be excluded from the Hindu temples of Brahmins[16] and they traditionally worship spirits in a practice known as Bhuta Kola. S. D. L. Alagodi wrote in 2006 of the South Canara population that "Among the Hindus, a little over ten per cent are Brahmins, and all the others, though nominally Hindus, are really propitiators or worshippers of tutelary deities and bhutas or demons."[17]

The venues for Bhuta Kola are temple structures called Bhutasthana or Garidi[b] as well as numerous shrines. The officiators at worship are a subcaste of Billavas, known as Poojary (priest),[19][20] and their practices are known as pooja.[21] Iyer noted that families often have a place set aside in their home for the worship of a particular Bhuta and that the worship in this situation is called Bhuta Nema.[22]

Iyer, who considered the most prevalent of the Billava Bhutas to be the twin heroes Koti and Chennayya,[23] also described the spirits as being of people who when living had

... acquired a more than usual local reputation whether for good or evil, or had met with a sudden or violent death. In addition to these, there are demons of the jungle, and demons of the waste, demons who guard the village boundaries, and demons whose only apparent vocation is that of playing tricks, such as throwing stones on houses and causing mischief generally.[24]

More recently, Ghosh has described a distinction between the Bhuta of southern India, as worshipped by the Billavas, and the similarly named demons of the north

In northern India the word bhuta generally refers to a ghost or a malign presence. Tulu bhutas, on the other hand, though they have their vengeful aspects, are often benign, protective figures, ancestral spirits and heroes who have been assimilated to the ranks of minor deities.[25]

Bhuta Kola is a cult practised by a large section of Tulu Nadu society, ranging from landlords to the Dalits, and the various hierarchical strands all have their place within it. While those at the top of this hierarchical range provide patronage, others such as the Billava provide the practical services of officiating and tending the shrines, while those at the bottom of the hierarchy enact the rituals, which include aspects akin to the regional theatrical art forms known as Kathakali and Yakshagana.[25] For example, the pooja rituals include devil-dancing, performed by the lower class Paravar[c] or Naike,[21] and the Bunts – who were historically ranked as superior to the Billava[d]– rely upon the Poojary to officiate.[20]

There was a significance in the Bunt landholdings and the practice of Bhuta worship. As the major owners of land, the Bunts held geographic hubs around which their tenant farmers and other agricultural workers were dispersed. The Billavas, being among the dispersed people, were bonded to their landlords by the necessities of livelihood and were spread so that they were unable to unite in order to assert authority. Furthermore, the Bhuta belief system also provided remedies for social and legal issues: it provided a framework for day-to-day living.[28]

Thurston noted that Baidya was a common name among the community, as was Poojary. He was told that this was a corruption of Vaidya, meaning a physician.[18]

Traditional occupations

[edit]

Heidrun Brückner describes the Billavas of the nineteenth century as "frequently small tenant farmers and agricultural labourers working for Bunt landowners."[28] Writing in 1930, Iyer described the community as being involved mostly in toddy tapping, although they also had involvements in agriculture and in some areas were so in the form of peasant tenant landholders known as raiyats.[16] This was echoed in a report of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research of 1961, which said that "The Billavas are concentrated mostly in South Kanara district. Though toddy tappers by profession, they rely mostly on cultivation. They are generally small landowners or lessees ..."[29]

According to Ghosh, "By tradition, [the Billavas] are also associated with the martial arts and the single most famous pair of Tuluva heroes, the brothers Koti-Chennaya, are archetypal heroes of the caste who symbolize the often hostile competition between the Billavas and the Bunts."[30] Neither Thurston nor Iyer make any reference to this claim.

Culture

[edit]Tuluva paddanas are sung narratives which are part of several closely related singing traditions, similar to Vadakkan Pattukal (Northern ballads) of northern Kerala and which may be considered ballads, epics or ritual songs (depending on the context or purpose for which they are sung). The community has special occasions in which it is traditional to sing paddanas. They will sing the Paddana of Koti-Chennaya during a ceremony on the eve of a marriage. Women who sing the song in the fields will sing those verses appropriate for the young heroes.[31]

Social changes

[edit]The Billava community suffered ritual discrimination under the Brahmanic system—of which the caste system in Kerala was perhaps the most extreme example until the twentieth century. They were, however, allowed to live in the same villages as Brahmins.[16]

Some Billavas had seen the possibility of using religion as a vehicle for the social advancement of their community, as the Paravars had previously attempted in their conversion to Christianity.[32] The British had wrested the region from the control of Tipu Sultan in 1799, as a consequence of the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, and in 1834 the Christian Basel Mission arrived in Mangalore. These evangelists were among the first to take advantage of a relaxation of rules that had prevented non-British missionaries from working in India, and theirs was the first Protestant mission of any nationality in the area.[33] They initially condemned the caste system because it was an inherent part of the Hindu religion and therefore must be wrong, but they came to see the divisions caused by it as being evil in their own right and took to undermining it as a matter of social justice.[34] They considered the stratification of the caste system as being contrary to Christian values, which proclaimed that all were equal in the eyes of God.[35] These missionaries had some success in converting native people, of which those converted from among the Billavas formed the "first and largest group".[34] Brückner describes the Billavas as being "the strongest group among the converts" and that, along with the Bunts, they were "the mainstays of the popular local religion, and the mission was probably induced by this target group to occupy itself with its practices and oral literature."[28]

Alagodi notes that the

... motives for conversion were not always purely religious. Support against oppression by landlords and money lenders, hope for better social standards, education for their children, chances of employment in the mission's firms, the prospect of food provision, clothing, shelter and a decent state of life—such motives might have contributed to their decision for baptism. The chief motive, however, seems to have been a revolt against the social order dominated by demons or bhutas. The conversion offered them forgiveness of sin and liberation from the social conditions that would hold them back if they remained in the Hindu fold. ... Many people thought that the God of the missionaries was greater and more powerful than the demons.[36]

However, the conversion of Billavas to Christianity did not always run smoothly. The Basel missionaries were more concerned with the quality of those converted than with the quantity. In 1869 they rejected a proposition that 5000 Billavas would convert if the missionaries would grant certain favours, including recognition of the converts as a separate community within the church and also a dispensation to continue certain of their traditional practices. The missionaries took the view that the proposition was contrary to their belief in equality and that it represented both an incomplete rejection of the caste system and of Hindu practices. Alagodi has speculated that if the proposition had been accepted then "Protestant Christians would have been perhaps one of the largest religious communities in and around Mangalore today."[35] A further barrier to conversion proved to be the Billava's toddy tapping occupation: the Basel Mission held no truck with alcohol, and those who did convert found themselves economically disadvantaged, often lacking both a job and a home.[37] This could apply even if they were not toddy tappers: as tenant farmers or otherwise involved in agriculture, they would lose their homes and the potential beneficence of their landlords if they converted.[28] The Mission attempted to alleviate this situation by provision of work, principally in factories that produced tiles and woven goods.[37][e]

Nireshvalya Arasappa—described by Kenneth Jones as "one of the few educated Billavas"—was one such person who looked to conversion from Hinduism as a means to advancement during the nineteenth century. Having initially examined the opportunities provided by Christian conversion, Arasappa became involved with the Brahmo Samaj movement in the 1870s and he arranged for Brahmo missionaries to meet with his community. The attempt met with little success: the Billavas were suspicious of the Brahmo representatives, who wore western clothing and spoke in English[32] whereas the Basel Missionaries had studied the local languages and produced a copy of the New Testament in both Tulu and Kannada.[2]

Kudroli Gokarnanatheshwara Temple

[edit]

Ezhavas, a kindred community from Kerala, were organised by Narayana Guru in establishing social equality through his temple in Sivagiri. Using the same principles, Billavas established a temple. After the construction of the Kudroli Gokarnanatheshwara Temple at Mangalore, Naryana Guru asked community leaders to work together for mutual progress by organising schools and industrial establishments; in accordance with his wishes, many Sree Narayana organisations have sprung up in the community.[38][39]

Similar communities

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ L. K. Ananthakrishna Iyer's The Mysore Tribes and Castes, published in 1930, contains numerous sentences that appear also in Edgar Thurston's The Castes and Tribes of Southern India of 1909. In turn, Thurston's work used material that had previously been published by other British Raj sources, and not always with clear attribution of this fact. This situation makes it difficult to distinguish individual opinions and it has to be understood in the context of the multiple publications produced under the aegis of the Ethnographic Survey of India that was established in 1901 on the basis of the work of Herbert Hope Risley.

- ^ Thurston called the Bhutasthana "devil shrines" and appears to distinguish them from Garidi but does not explain why he did so: "Some Billavas officiate as priests (pujaris) at bhutasthanas (devil shrines) and garidis."[18]

- ^ Iyer called these devil-dancers the Pombada but Thurston refers to the Paravar community.[26]

- ^ Amitav Ghosh quotes Francis Buchanan, who said of the Billava that they "pretend to be Shudras, but acknowledge their inferiority to the Bunts."[20] Shudra is the lowest ritual rank in the Hindu varna system, below which are the outcastes. Buchanan travelled through South Canara in 1801, soon after the British took control of it.[27] Ghosh notes that "until quite recently [the Bunts] controlled most of the land in Tulunad" and their influence in Bhuta worship was notable because of this.[20]

- ^ The first of seven weaving factories operated by the Basel Mission was established in 1851, and the first of a similar number of tile factories in 1865.[37]

Citations

- ^ a b c d Iyer, L. Krishna Ananthakrishna (1930). The Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. II. Mysore: Mysore University Press. p. 288. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ a b Brückner, Heidrun (2009). On an Auspicious Day, at Dawn: Studies in Tulu Culture and Oral Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 4. ISBN 978-3-447-05916-9. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ Dev, Arun (13 April 2023). "Caste equations may trump Hindutva plank in coastal Karnataka". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 30 April 2025.

- ^ "Billava ministers attempting to scuttle community struggle, alleges Pranavananda Swami". The Hindu. 11 July 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2025.

- ^ Ghosh, Amitav (2003). The Imam and the Indian: prose pieces (Third ed.). Orient Blackswan. pp. 195–197. ISBN 978-81-7530-047-7. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Thurston, Edgar (1909). The Castes and Tribes of Southern India, A – B. Vol. I. Madras: Government Press. p. 244. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ a b Bhat, D. N. S. (1998). "Tulu". In Steever, Sanford B. (ed.). The Dravidian languages. Taylor & Francis. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-0-415-10023-6. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Alagodi, S. D. L. (2006). "The Basel Mission in Mangalore: Historical and Social Context". In Wendt, Reinhard (ed.). An Indian to the Indians?: on the initial failure and the posthumous success of the missionary Ferdinand Kittel (1832–1903). Studien zur aussereuropäischen Christentumsgeschichte. Vol. 9. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 132. ISBN 978-3-447-05161-3. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ Thurston, Edgar (1909). The Castes and Tribes of Southern India, A – B. Vol. I. Madras: Government Press. pp. 243–244. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ a b Iyer, L. Krishna Ananthakrishna (1930). The Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. II. Mysore: Mysore University Press. p. 290. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ a b Ghosh, Amitav (2003). The Imam and the Indian: prose pieces (Third ed.). Orient Blackswan. p. 193. ISBN 978-81-7530-047-7. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Iyer, L. Krishna Ananthakrishna (1930). The Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. II. Mysore: Mysore University Press. p. 289. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Iyer, L. Krishna Ananthakrishna (1930). The Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. II. Mysore: Mysore University Press. pp. 294–295. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Hastings, James, ed. (1908). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Vol. 4. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 604. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- ^ Thurston, Edgar (1909). The Castes and Tribes of Southern India, A – B. Vol. I. Madras: Government Press. pp. 246–247. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ a b c Iyer, L. Krishna Ananthakrishna (1930). The Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. II. Mysore: Mysore University Press. p. 295. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Alagodi, S. D. L. (2006). "The Basel Mission in Mangalore: Historical and Social Context". In Wendt, Reinhard (ed.). An Indian to the Indians?: on the initial failure and the posthumous success of the missionary Ferdinand Kittel (1832–1903). Studien zur aussereuropäischen Christentumsgeschichte. Vol. 9. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 142. ISBN 978-3-447-05161-3. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ a b Thurston, Edgar (1909). The Castes and Tribes of Southern India, A – B. Vol. I. Madras: Government Press. p. 246. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Iyer, L. Krishna Ananthakrishna (1930). The Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. II. Mysore: Mysore University Press. pp. 289–290. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d Ghosh, Amitav (2003). The Imam and the Indian: prose pieces (Third ed.). Orient Blackswan. p. 195. ISBN 978-81-7530-047-7. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ a b Iyer, L. Krishna Ananthakrishna (1930). The Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. II. Mysore: Mysore University Press. pp. 293–294. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Iyer, L. Krishna Ananthakrishna (1930). The Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. II. Mysore: Mysore University Press. pp. 291, 293. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Iyer, L. Krishna Ananthakrishna (1930). The Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. II. Mysore: Mysore University Press. p. 292. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Iyer, L. Krishna Ananthakrishna (1930). The Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. II. Mysore: Mysore University Press. pp. 290–291. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ a b Ghosh, Amitav (2003). The Imam and the Indian: prose pieces (Third ed.). Orient Blackswan. p. 192. ISBN 978-81-7530-047-7. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Thurston, Edgar (1909). The Castes and Tribes of Southern India, A – B. Vol. I. Madras: Government Press. p. 250. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Ghosh, Amitav (2003). The Imam and the Indian: prose pieces (Third ed.). Orient Blackswan. p. 194. ISBN 978-81-7530-047-7. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d Brückner, Heidrun (2009). On an Auspicious Day, at Dawn: Studies in Tulu Culture and Oral Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 5. ISBN 978-3-447-05916-9. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ Randhawa, Mohinder Singh (1961). Farmers of India: Madras, Andhra Pradesh, Mysore & Kerala. Vol. 2. Indian Council of Agricultural Research. p. 269. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Ghosh, Amitav (2003). The Imam and the Indian: prose pieces (Third ed.). Orient Blackswan. p. 196. ISBN 978-81-7530-047-7. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Peter J. Claus, "Variability in the Tulu Paddanas". Archived 8 July 2012 at archive.today Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ a b Jones, Kenneth W. (1989). Socio-religious Reform Movements in British India. Vol. Part 3, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-521-24986-7. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Alagodi, S. D. L. (2006). "The Basel Mission in Mangalore: Historical and Social Context". In Wendt, Reinhard (ed.). An Indian to the Indians?: on the initial failure and the posthumous success of the missionary Ferdinand Kittel (1832–1903). Studien zur aussereuropäischen Christentumsgeschichte. Vol. 9. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 133–134. ISBN 978-3-447-05161-3. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ a b Alagodi, S. D. L. (2006). "The Basel Mission in Mangalore: Historical and Social Context". In Wendt, Reinhard (ed.). An Indian to the Indians?: on the initial failure and the posthumous success of the missionary Ferdinand Kittel (1832–1903). Studien zur aussereuropäischen Christentumsgeschichte. Vol. 9. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 142–144. ISBN 978-3-447-05161-3. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ a b Alagodi, S. D. L. (2006). "The Basel Mission in Mangalore: Historical and Social Context". In Wendt, Reinhard (ed.). An Indian to the Indians?: on the initial failure and the posthumous success of the missionary Ferdinand Kittel (1832–1903). Studien zur aussereuropäischen Christentumsgeschichte. Vol. 9. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 150. ISBN 978-3-447-05161-3. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ Alagodi, S. D. L. (2006). "The Basel Mission in Mangalore: Historical and Social Context". In Wendt, Reinhard (ed.). An Indian to the Indians?: on the initial failure and the posthumous success of the missionary Ferdinand Kittel (1832–1903). Studien zur aussereuropäischen Christentumsgeschichte. Vol. 9. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 145. ISBN 978-3-447-05161-3. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ a b c Alagodi, S. D. L. (2006). "The Basel Mission in Mangalore: Historical and Social Context". In Wendt, Reinhard (ed.). An Indian to the Indians?: on the initial failure and the posthumous success of the missionary Ferdinand Kittel (1832–1903). Studien zur aussereuropäischen Christentumsgeschichte. Vol. 9. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-3-447-05161-3. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ "At Indian temple, widows from lowest caste are exalted as priests". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Udupi: Chapter on Sri Narayana Guru to be part of school syllabus". Daiji World.

Billava

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Identity

Etymology

The term Billava is derived from the Dravidian root billu or biru, meaning "bow" in Tulu and related languages, combined with the suffix -ava or -avan (indicating "person" or "he" in Kannada), yielding "bowman" or "archer." This etymology underscores the community's ancestral proficiency in archery and martial traditions, such as garudi wrestling and weapon-based combat, which were integral to their identity as protectors and toddy tappers in Tulunadu.[9][3] Anthropological records from the early 20th century describe Billava as a contraction of Billinavaru ("bowmen"), a designation tied to their historical role as skilled archers employed by local rulers for warfare and security in coastal Karnataka.[10] Alternative derivations link the name to proto-Dravidian terms for archers, paralleling ancient Tamil Villavar (bowmen) associated with the Chera dynasty and Bhil tribal groups, suggesting possible migrations or cultural affinities among pre-Aryan Dravidian communities.[11][12] These connections are supported by shared symbolism in folklore and rituals, though direct genetic or epigraphic evidence remains limited, with interpretations varying across ethnographic accounts.[8]Historical and Mythological Origins

The Billava community is regarded as among the aboriginal inhabitants of Tulunadu, the coastal region encompassing parts of present-day Dakshina Kannada and Udupi districts in Karnataka, with evidence of their presence tied to ancient practices such as archery, healing, and toddy extraction from coconut palms.[2] Ethnographic accounts describe them as the numerically dominant group in South Canara during the early 20th century, comprising approximately one-fifth of the local population and maintaining distinct roles in warfare, temple rituals, and midwifery.[10] Their etymology, derived from Kannada roots meaning "bow user" (billu + ava), reflects historical associations with martial traditions, including the use of bows and arrows in regional conflicts and hunting.[3] While inscriptions explicitly mentioning Billavas date to the 15th century CE, oral histories and cultural continuity suggest deeper antiquity, potentially linking them to pre-Dravidian settlers through persistent indigenous customs like bhuta (spirit) worship.[2] Mythologically, Billavas center their identity around the legend of the twin heroes Koti and Chennayya, revered as deified bhutas symbolizing resistance to feudal oppression. According to folklore recorded in ethnographic surveys, the twins descended from an excommunicated Brahman woman and a Billava man, born into a toddy-tapper family in the 16th century CE near Padumale; they trained in martial arts, defied a tyrannical king by stealing ritual horses, and were ultimately killed in battle, ascending as protective spirits.[10] This narrative, elaborated in the epic Koti Chennayya Pad'dana, underscores themes of valor and communal solidarity, with the brothers' exploits commemorated in annual rituals and garadi (martial training) halls across Tulunadu.[2] A parallel tradition involves the Baidya (physician) lineage, where two Billava brothers received esoteric medical and magical texts from a sanyasi mentor, establishing hereditary healing practices that integrated herbal knowledge with ritual elements.[10] These myths, preserved through oral epics and bhuta kola (spirit possession dances), reinforce Billava claims to indigenous spiritual authority, though they blend historical kernels—such as regional power struggles under Ballala kings—with symbolic etiology rather than verifiable chronology.[2]Genetic and Anthropological Perspectives

Anthropological accounts portray the Billava as indigenous inhabitants of Tulunadu, the coastal region encompassing present-day Dakshina Kannada and Udupi districts in Karnataka, with roots tracing to pre-caste societal structures centered on lineages known as bari systems. Traditionally associated with occupations such as archery, hunting, toddy tapping from palm trees, and service as soldiers, they maintained distinct cultural practices including spirit worship (bhuta kola) and matrilineal inheritance (aliya santana) in earlier periods, reflecting adaptation to the agrarian and forested landscape of the region.[3][2] These traits position them among aboriginal groups like the Mogeras and Malekudiyas, predating significant Dravidian or Indo-Aryan migrations, though their warrior ethos—evident in hero stone inscriptions (viragallu) commemorating martial exploits—suggests possible links to ancient Dravidian archer clans termed Villavars.[13][9] Genetic research on the Billava remains sparse and often embedded within broader analyses of southwest coastal populations, but available data align them with Dravidian-speaking groups exhibiting high Ancestral South Indian (ASI) ancestry, indicative of deep indigenous continuity in peninsular India. Paternal lineages show the presence of Y-chromosomal haplogroup O2a1-M95 among Billava samples, a marker linked to late Neolithic expansions from eastern to western India, potentially tied to early agricultural dispersals rather than later Indo-European influences.[14] Studies of related toddy-tapper communities, such as Thiyya (equated with Billava in Tulunadu), reveal elevated west Eurasian or northwest Indian paternal gene flow via Y-microsatellite markers, suggesting historical male-mediated admixture events, possibly from trade or migration along coastal routes, while maternal mtDNA lineages retain strong Indian-specific clustering.[15] Overall, these findings underscore a predominantly ASI foundation with variable ANI contributions, consistent with endogamous practices reinforcing local genetic structure amid regional diversity.[16]Demographics and Social Framework

Population Distribution and Size

The Billava community is predominantly concentrated in the coastal districts of Karnataka, particularly Dakshina Kannada, Udupi, and Uttara Kannada, which collectively form the Tulu Nadu region. These areas account for the majority of their population, with smaller communities present in neighboring Shivamogga district and through migration to urban centers such as Bengaluru and Mumbai.[8][17] In these coastal districts, Billavas constitute a dominant demographic group, estimated at around 18% of the local population according to political scientist Valerian Rodrigues. A 2024 community assessment places their numbers at approximately 12 lakh across Dakshina Kannada, Udupi, Karwar (in Uttara Kannada), and Shivamogga districts.[18][17] Precise statewide figures are unavailable due to the absence of sub-caste breakdowns in official censuses, but estimates suggest the community exceeds 20 lakh primarily within Karnataka's coastal belt, reflecting their historical ties to toddy-tapping and agriculture in the region.[8] Smaller diaspora populations exist in Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Gulf countries, though these represent a fraction of the total.[19]Language and Dialects

The Billava community predominantly speaks Tulu, a Dravidian language native to the Tulu Nadu region encompassing Dakshina Kannada and Udupi districts in coastal Karnataka.[10] This language serves as their primary medium of communication, reflecting their historical concentration in South Canara (now parts of coastal Karnataka).[2] Within Tulu, Billavas typically employ the common Tulu dialect, which is the most widespread variant used for commerce, trade, and daily interactions among multiple castes including Billavas, Bunts, and Mogaveera.[9] In northern and inland extensions of their settlement areas, such as around Kundapur and Byndoor, some Billavas have adopted Kannada as a spoken language, particularly over the last 100–150 years, while historically maintaining Tulu in domestic settings.[2] Those identifying as "Kannada Billavas" integrate Kannada into their linguistic practices, often alongside Tulu, due to regional administrative and educational influences.[9] A distinct subgroup, the Maliyali Billavas, speaks a specialized dialect of Malayalam incorporating lexical elements from Tulu, Beary, and other local tongues, primarily in areas bordering Kerala.[20] Tulu as a whole features four broadly similar dialects with minor phonological and lexical variations, but no unique Billava-specific subdialect beyond the common form has been documented in ethnographic records.[21]Subgroups and Internal Divisions

The Billava community features occupational subgroups such as Poojari, who function as priests officiating bhuta (spirit) worship ceremonies at sacred sites known as bhutasthanas and garodis, often wearing a distinctive gold bangle and credited with invoking deities for healing and rituals.[10] Baidya (or Baida), another subgroup, specializes in traditional herbal medicine and serpent worship (nagaradhana), deriving from the term Vaidya meaning physician, with members sometimes serving in priestly roles tied to magical and medicinal practices.[10] [9] These divisions reflect historical specialization in ritual and healing, predating Vedic influences, though intermarriage occurs within the broader community.[3] Regional distinctions further delineate the group, with Tulu Billava predominant in coastal Karnataka's Tulu Nadu, speaking Tulu and adhering to local customs, contrasted by Malayali Billava (also termed Thiyya Billava, Belchada, or Belchand) in Kerala-adjacent areas, who speak Malayalam or Byari and worship deities like Bhagavathi.[22] [9] In northern taluks like Kundapur, a subgroup known as Halepaika (or Hale Paikaru) engages in toddy drawing using Kanarese speech and distinct tools, such as stone weights versus bone, marking linguistic and methodological variations from southern counterparts around Udupi.[10] Internally, marriage is regulated by exogamous septs called balis, matrilineally inherited under the Aliya Santana system, traditionally numbering twenty and serving as sub-divisions to prevent endogamy within clans; common baris (clans) include Suvarna, Amin, and Kotian, with additional koodubaris like Pergade.[10] [3] These structures, alongside titles like Deevar in Shimoga district, underscore a flexible hierarchy influenced by geography and occupation rather than rigid subcaste endogamy.[22]Family and Life Cycle Rituals

Marriage Customs and Practices

The Billava community traditionally adheres to the matrilineal Aliya Kattu (or Aliya Santana) system of inheritance and marriage, wherein property descends through the female line to the sister's son (nephew), and the groom typically integrates into the bride's household after marriage.[23] [24] This system emphasizes nephew lineage, prohibiting unions with a sister's daughter or mother's sister's daughter while permitting marriages to a paternal aunt's daughter or maternal uncle's daughter.[23] [9] Exogamy is enforced within Bari subgroups—clusters of families sharing common ancestry—to preserve social harmony and prevent intra-clan unions.[25] Marriage rituals, as documented in early 20th-century ethnographies, span two days and involve preparatory purificatory ceremonies for an adult bride (dhāre), conducted one or two days prior.[10] On the wedding day, the bride and groom are seated on separate planks atop a dais, with a barber arranging ritual items including rice, flowers, lamps, betel leaves, and areca nuts for symbolic exchanges and invocations.[10] Widow remarriage is permitted, though with abbreviated rites compared to first marriages.[12] Premarital intercourse resulting in pregnancy mandates a simplified union rite known as bidu dhāre to legitimize the offspring within the matrilineal framework.[26] The community practices posthumous marriage for unmarried deceased individuals, particularly to ensure ancestral continuity or resolve spiritual obligations, a custom shared with select other South Indian groups like the Badagas and Todas.[27] [23] While these traditions reflect historical matrilineal norms in Tulunadu, contemporary Billava marriages increasingly incorporate patrilineal elements influenced by Hindu reform movements and legal changes, diminishing strict Aliya Kattu adherence since the mid-20th century.[12]Inheritance and Property Rights

The Billava community in coastal Karnataka traditionally adhered to the Aliyasantana, also known as Aliya Kattu, a matrilineal inheritance system shared with groups like the Bunts in Tulu Nadu.[28] In this framework, property succession followed the female line, with a man typically transmitting assets to his nephew (the son of his sister) rather than to his own sons, emphasizing lineage continuity through maternal kinship.[28] Family property was held jointly within the taravadu (extended matrilineal household), where children were considered members of the mother's family, and post-marriage, the wife retained residence in her natal home while the husband contributed to its management.[28] Property rights vested primarily in female members and their descendants, with daughters inheriting shares to perpetuate the family name and assets; sons received portions for personal use, but these did not confer inheritance rights to their wives or children under customary rules.[28] The eldest family member, termed Yejaman (male) or Yejamanthi (female), oversaw joint holdings, including finances and land, often with maternal uncles playing key supportive roles in decision-making and resource allocation after the matriarch's passing.[28] Partition or division of ancestral property required the head's explicit approval, preventing unilateral claims and preserving communal tenure, though individual members could seek separation with consent.[28] Legal interventions, including amendments to the Indian Succession Act around 1962, eroded these customs by granting wives and direct heirs of deceased males claims to portions of estates previously excluded, facilitating transitions to individualized ownership and nuclear families.[28] By the 2010s, Aliya Kattu had largely ceased among Billavas, supplanted by patrilineal Hindu inheritance norms under statutory law, though vestiges persisted symbolically in rituals like daughters preparing mortuary feasts.[29] This shift aligned with broader socio-economic changes, including urbanization and the influence of reform movements, reducing joint family dependencies on toddy-tapping lands and ancestral holdings.[28]Death and Funeral Observances

Among the Billava, the deceased are typically cremated, though burial is practiced in certain instances.[10] [30] The body is prepared by washing it, placing it on a plantain leaf, and covering it with a new cloth; unhusked rice (paddy) is heaped near the head and feet, and coconut halves with lighted wicks are positioned accordingly, sometimes on a throne-like seat (gaddī).[10] [30] Relatives and friends sprinkle water infused with tulsi (Ocimum sanctum) leaves into the mouth of the corpse.[10] The body, wrapped in banana leaves and anointed with coconut and turmeric, is carried on a plank or men's shoulders to the cremation ground, where Holeya community members gather wood for the pyre—excluding Strychnos nux-vomica—and a Madhivala (washerman) may officiate as priest; the pyre is ignited at both ends using a mango tree trunk.[10] [30] On the fifth day, ashes are gathered and interred at the site; for burials, a straw effigy is cremated over the grave, followed by similar ash disposal.[10] A conical mound (dhūpe) is raised, topped with a tulsi plant, alongside an opened tender coconut, tobacco leaf, betel leaves, and areca nuts.[10] The family enters a period of ritual pollution (sūtaka), culminating in purification after 11 days, which may involve dramatizing death as an old woman announcing the deceased's afterlife transition.[30] The 13th-day bojja ceremonies mark a key observance, involving construction of ritual cars: a small bamboo tiered car (Nīrneralu) at home, decorated with cloths and holding the deceased's jewels and clothes under a suspended lamp, and an upparige framework around the dhūpe.[10] Rice is measured and washed by women, mixed with jaggery and coconut, and offered in a cup turned upside down on a plantain leaf; sons-in-law receive new cloths, and water rituals occur at a coconut tree.[10] Items are bundled, processed in a palanquin—potentially with Nalke or Parava devil-dancers portraying bhūtas—to the upparige, circled thrice, unpacked, and augmented with rice or produce before dismantling.[10] On the 14th day, food is offered to crows, concluding the rites.[10] In cases of death on an inauspicious day, the Kāle deppuni rite expels the ghost: ashes are strewn indoors with doors closed, followed by sprinkling turmeric water on the roof and beating it with Zizyphus oenoplia twigs; upon reopening, cloven footprints in the ashes confirm departure, or a magician intervenes.[10] For unnatural deaths producing pretas (restless ghosts), especially of the unmarried or violently deceased, appeasement may occur in garōdis (community shrines), including symbolic preta marriages under bhūtas like Koti and Chennaya to integrate the spirit and avert torment.[30] These practices, rooted in Tulu Nadu traditions, blend Hindu elements with local bhūta veneration, though specifics vary by locality and era.[10] [30]Religious Beliefs and Practices

Traditional Bhuta Worship

Traditional Bhuta worship, also termed Bhuta Kola or Bhuta Aradhane, forms the cornerstone of Billava religious life in Tulu Nadu, involving the ritual invocation and propitiation of local spirits (bhutas or daivas) believed to embody ancestors, heroes, and natural forces for protection, justice, and dispute resolution.[31] These practices, rooted in pre-Hindu animism, feature trance-induced possession of performers who, under the spirit's influence, deliver oracles, enforce moral codes, and address communal grievances through dance, music, and symbolic enactments.[32] Unlike Brahmanical temple rituals from which Billavas were historically excluded, Bhuta worship emphasizes direct, egalitarian access to the divine, with ceremonies held in sacred groves (daivasthanas) or garodis (martial halls doubling as shrines), often annually or during crises.[33] Billavas predominantly serve as officiants, with priests (pujaris or patris) from the community's Poojary subcaste preparing altars, reciting invocations, and managing the rite's progression, while possessed dancers—typically lower-status individuals—embody the bhutas via elaborate costumes, masks, and vigorous movements synchronized to drumbeats and folk instruments like the damaru.[34] Paddanas, epic oral narratives in Tulu, accompany the rituals, recounting the bhuta's origin, exploits, and attributes to induce possession and affirm cultural continuity; for instance, verses detail heroic feats to invoke valorous spirits.[33] Offerings include rice, coconut, and animal sacrifices in some cases, followed by feasting that reinforces kinship ties, though the core efficacy lies in the bhuta's perceived intervention in real-world affairs, such as averting calamities or arbitrating land disputes.[31] Prominent bhutas venerated by Billavas include Koti and Chennaya, deified twin warriors from the community circa 1556–1591 CE, renowned for combating feudal oppression and symbolizing martial prowess and dharma; their garodis host wrestling and weapons training alongside worship, blending spiritual and physical discipline.[35] Other key figures encompass Panjurli, a daiva or spirit deity revered as a divine wild boar and central to Bhuta Kola, symbolizing nature's guardianship, justice, and fertility, Jumadi (fierce protector), Kallurti, and maternal spirits like Devi Baidedi, each tied to specific locales or functions, with rituals tailored to petition their aid—e.g., Panjurli invoked for communal protection and agricultural prosperity.[29] This pantheon reflects causal realism in Billava worldview, positing bhutas as active agents in ecological and social equilibrium rather than abstract ideals, sustained through empirical communal validation over generations.[32]Folk Deities and Possession Cults

Billavas traditionally worship a diverse array of folk deities known as bhutas (spirits or demons), which are regarded as protective entities influencing devotees' fortunes and resolving communal conflicts.[1] These practices form part of the broader bhuta aradhane (spirit worship) endemic to Tulu Nadu, where Billavas, as a significant demographic, participate actively as devotees and mediums.[6] Possession cults, particularly Bhuta Kola or nema, constitute the core mechanism, involving ritual invocation of bhutas through music, fasting, and ceremonial attire, culminating in trance states where the medium (patri or paatry) embodies the deity to dispense justice, oracles, and blessings.[6] Prominent among Billava-specific deities are the twin brothers Koti and Chennaya, deified heroes from folk epics (paddanas) embodying resistance against feudal oppression and symbolizing communal valor.[35] Their cult centers on garodis, multifunctional shrines functioning as gymnasiums for martial training and ritual spaces for possession ceremonies that mark rites of passage and reinforce social bonds.[35] In these rituals, Billava mediums channel the twins' spirits, often amid drumming and invocation, to address grievances, a practice historically tied to their roles as royal healers and patris under Tulu chieftains.[6] The reappropriation of this cult gained momentum in the mid-20th century, spurred by Billava intellectuals like Babu Amin and Damodar Kalmady, who adapted garodi rites to promote egalitarian ideals amid peasant uprisings and challenges to high-caste patronage of bhuta worship.[35] This revival, building on earlier influences from Basel Mission education since the 1830s, transformed possession practices into assertions of subaltern identity, democratizing access previously controlled by elites.[6] While Koti-Chennaya dominate, Billavas also honor regional bhutas like Jumadi (a serpent spirit) and Panjurli, a spirit deity revered as a divine wild boar central to Bhuta Kola and symbolizing nature's guardianship, justice, and fertility, integrating these into kola performances for fertility, protection, and exorcism.[36] Such cults persist as living traditions, blending animistic elements with community governance despite pressures toward Hinduization.[1]Impact of Social Reformers and Hinduization

The Billava community experienced significant religious transformation through the influence of Sree Narayana Guru (1856–1928), a Kerala-based reformer whose teachings emphasized equality, self-reliance, and the philosophy of "one caste, one religion, one God." His movement, which began in the early 1900s, resonated with Billavas in coastal Karnataka, encouraging them to reject mass conversions to Christianity promoted by the Basel Mission since the 1830s and instead pursue social elevation within Hinduism. Narayana Guru's advocacy for education and temple access inspired Billavas to establish inclusive institutions, such as the Kudroli Gokarnanath Temple in Mangalore, consecrated in 1912, which symbolized a shift toward mainstream Hindu practices and community solidarity.[37][4][38] This Hinduization process involved reappropriating traditional Bhuta possession cults, integrating them with Vedantic ideals to foster identity and resistance against caste oppression. Educated Billava elites, empowered by missionary schooling yet remaining Hindu, reformed rituals around folk heroes like Koti and Chennaya, framing martyrdom narratives as paths to salvation and social assertion rather than mere animism. Such reforms dissociated Bhuta worship from untouchability stigma, aligning it with structured Hindu devotion while preserving Tuluva cultural elements.[6][39] In the mid-20th century, organizations like the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), active among Billavas since the 1940s, further reinforced Hindu identity by incorporating them into broader Hindutva activities, such as through the Vishva Hindu Parishad and Bajrang Dal. While this provided a counter to lingering caste discrimination, it often preserved hierarchical structures, prompting ongoing demands for equitable representation. Narayana Guru's enduring legacy, however, drove foundational changes, enabling Billavas to leverage temple-centered practices for upward mobility without full assimilation into higher-caste norms.[4][37]Economic Roles and Livelihoods

Traditional Occupations in Toddy Tapping and Agriculture

The Billava community in Tulu Nadu, Karnataka, has long been identified with toddy tapping as a primary hereditary occupation, involving the extraction of sap from palm trees such as coconut and areca varieties endemic to the region's coastal agroecology.[6] This labor-intensive practice demanded exceptional physical agility, with tappers ascending trees—often exceeding 20 meters in height—using looped ropes or bare limbs to access inflorescences, where precise incisions allowed sap collection in earthen pots; the unfermented sap, known as neera, would naturally ferment within hours into toddy, a staple rural beverage and revenue source under pre-independence landholding systems.[40] Historical accounts from the early 20th century document Billavas as comprising a significant portion of South Canara's (now Dakshina Kannada and Udupi) toddy-tapping workforce, with estimates suggesting thousands engaged seasonally, though exact figures vary due to informal labor structures.[41] Complementing toddy tapping, agriculture formed a secondary yet integral livelihood, with Billavas typically operating as small tenant farmers or landless laborers under feudal arrangements dominated by landowning groups like Bunts.[2] Cultivation focused on wet-rice paddies, coconut groves, and areca plantations, utilizing rudimentary tools such as wooden plows and sickles adapted to the lateritic soils and monsoon-dependent cycles of Tulu Nadu; yields supported subsistence alongside toddy income, with crops like paddy, pulses, and plantation nuts integral to household economies by the 19th century.[2] This dual occupation reflected adaptive strategies to the agroforestry landscape, where palm-based tapping integrated with intercropping practices, though systemic land scarcity confined most Billavas to marginal holdings averaging under 2 hectares per family in colonial-era surveys.[42] These roles were not merely economic but embedded in social hierarchies, with toddy tappers often facing ritual pollution stigma that limited access to higher agrarian positions, prompting community-wide efforts by the mid-20th century to diversify away from these vocations amid urbanization.[6] Empirical records from missionary and census data underscore the prevalence, with Billavas accounting for a majority of Tulu Nadu's palm sap extractors into the 1940s, before mechanization and prohibition policies eroded traditional methods.[42]Transition to Modern Professions and Entrepreneurship

In the 20th century, the Billava community began transitioning from traditional roles in toddy tapping and agriculture to modern professions, facilitated by access to education through Basel Mission schools established in Mangalore around the mid-19th century and later institutions inspired by the teachings of Sree Narayana Guru.[37] This shift was accelerated by social reform movements that emphasized self-reliance and upward mobility, leading to increased literacy and entry into white-collar jobs, government service, and urban industries.[38] By the late 20th century, many Billavas migrated to cities such as Mumbai and opportunities in Gulf countries, diversifying into sectors like manufacturing, trade, and services, which provided economic stability beyond rural agrarian constraints.[37] Entrepreneurship emerged as a key avenue for economic empowerment, particularly in the hospitality sector, where Billavas capitalized on culinary traditions to establish restaurant chains and hotels. Notable examples include the Jayaram Banan Group, which operates a chain of restaurants, star-category hotels, budget accommodations, and industrial canteens, and Hotel Deepa Comforts in Mangalore, led by Ramesh Kumar.[43] The Sukh Sagar chain, founded in 1962 by Suresh Poojari from a modest background, expanded to over 22 outlets offering vegetarian fare, reflecting a pattern of scaling from small ventures to multi-city enterprises. Community-led initiatives, such as cooperative societies and the Billava Chamber of Commerce inaugurated in 2016, further supported business ventures by providing networks and resources, enabling transitions into real estate, tile manufacturing—stemming from early Basel Mission factories—and other commercial activities.[37] [43] This evolution has been marked by self-initiated reforms, including the construction of temples like Kudroli Gokarnanatha in 1912, which symbolized cultural assertion alongside economic diversification, though persistent caste barriers in some rural areas continue to influence mobility patterns.[38] Overall, these changes have positioned Billavas as a relatively prosperous group within coastal Karnataka, with contributions to politics and industry underscoring their adaptation to post-independence urbanization and liberalization.[37]Cultural Heritage

Folklore, Literature, and Heroic Narratives

The folklore of the Billava community centers on the legendary twin warriors Koti and Chennayya, whose epic narrative embodies resistance to oppression and martial valor in Tulu Nadu. Born circa 1556 to Deyi Baidethi, a Billava woman who had saved the life of the local ruler Perumal Ballal, the twins were prophesied to bring fame to their lineage and trained rigorously in archery, wrestling, and other martial arts from childhood.[44][45] Their story, preserved as one of the longest Tulu epics, recounts their quests for cultivable land, confrontations with tyrannical figures like the envious Budyanata, and battles against feudal injustices between approximately 1559 and 1591.[35] In heroic deeds, Koti and Chennayya are depicted as protectors of their community, engaging in feats such as outwitting royal schemes, defending the weak, and upholding dharma through combat, often invoking divine aid from local deities. Their narrative culminates in a glorious martyrdom during a final confrontation with enemies near Yenmoor, where they perish fighting rather than submit, symbolizing self-sacrifice for collective honor.[46][35] This oral epic, transmitted through paddanas—traditional Tulu folk ballads sung by women during agricultural work, marriage eve ceremonies, or community gatherings—serves as both literature and ritual device, reinforcing Billava identity and ethical codes.[35][44] Garodis, the community's traditional gymnasia dedicated to these heroes, function as sites for enacting elements of the legend through physical training and mock combats, blending folklore with lived practice to instill discipline and solidarity. The twins' deification as bhutas (spirits) integrates their heroic narrative into possession cults, where performers channel their spirits to resolve disputes or affirm caste pride, as documented in ethnographic accounts from the late 19th century.[10] Modern retellings, such as Babu Amin's 1982 Koti Chennaya (translated as The Tale of the Twin Warriors in 2009) and Damodar Kalmady's 2007 Epic of the Warriors, adapt the paddanas into written form while preserving their inspirational role in Billava socio-political mobilization.[35] These narratives underscore empirical patterns of community resilience, drawing from verifiable oral traditions rather than unsubstantiated myths.Festivals, Arts, and Community Events

The Billava community participates in cultural festivals that emphasize heritage preservation, artistic expression, and social cohesion, often organized by sanghas or associations. The annual Billava Chavadi, hosted by groups like the Billava Sangha, features vibrant performances including traditional dances, music, and talent competitions, alongside tributes to reformers such as Narayana Guru. For instance, the 2022 edition in Kuwait incorporated Diwali lighting ceremonies and cultural skits, drawing hundreds to celebrate unity and artistic talent. These events, typically held in September or October, extend to diaspora communities and include elements of Tulu Nadu folklore adapted for modern stages.[47][48] Community gatherings such as the Vishwa Sammelana, convened by the Brahmashri Narayana Guru Seva Sangha, integrate beach festivals with cultural programs, as seen in the three-day event at Sasihithlu beach from January 24 to 26, 2025, which showcased local arts and promoted inter-community dialogue. These sammelanas often feature folk singing of paddanas—narrative ballads recounting heroic exploits—and martial arts demonstrations from garadi traditions, where practitioners perform synchronized routines with sticks and ropes, rooted in historical self-defense practices. Such displays highlight the community's transition from agrarian roots to contemporary cultural assertion.[49] Arts within Billava events draw from garadi mane centers, which host exhibitions of physical prowess and rhythmic exercises blending combat techniques with performative elements, occasionally integrated into festival side programs for youth engagement. Organizations like the Kannadiga Kalavidara Paristhat have held dedicated cultural arts festivals at venues such as Billava Bhavan in Mumbai, focusing on Kannada-Tulu performances to sustain linguistic and performative traditions amid urbanization. These initiatives underscore self-organized efforts to maintain artistic vitality without reliance on external patronage.[50]Cuisine and Daily Customs

The cuisine of the Billava community, rooted in the coastal Tulu Nadu region of Karnataka, emphasizes rice-based staples, coconut, and spices, with a prominence of non-vegetarian dishes reflecting local availability of seafood and poultry. Dishes such as neer dosa (thin rice-flour crepes), patrode (fermented colocasia leaves steamed in batter), kori rotti (crispy rice discs paired with dry chicken curry or ghee roast), and chicken sukka (coconut-spiced chicken) form core elements, often accompanied by tangy chutneys and pulimunchi (fish curry).[51] These preparations highlight the use of fresh, local ingredients and bold flavors typical of Mangalorean-Tuluva culinary traditions, which Billavas share as a major ethnic group in the area.[52] Toddy (kallu or palm wine), extracted from coconut or areca palms, serves as a traditional fermented beverage integral to Billava food culture, derived from their historical role in toddy tapping. Consumed fresh or mildly fermented for its mildly sweet, effervescent quality, it accompanies meals and social gatherings, though excessive use has drawn reformist critiques within the community.[10] Community events like the annual Atidonji Dina ritual feature handmade noodles prepared using the traditional seme mane (noodle-making tool), alongside other heritage dishes, reinforcing culinary continuity.[53] Daily customs among Billavas traditionally center on agrarian and extraction labors, particularly toddy tapping, which involves skilled climbing of palms at dawn to tap sap from flower-spathes crushed with stones or tools to initiate flow.[10] This labor-intensive routine, carried out by men using gourds or pots to collect and transport the sap, underscores a rhythm tied to natural cycles and simple, sustenance-focused living, with meals often communal and prepared over wood fires using earthenware. Modern transitions to urban professions have adapted these practices, yet toddy remains symbolically linked to identity in folklore and events.[3]Path to Socio-Economic Empowerment

Historical Barriers and Self-Initiated Reforms

The Billava community in coastal Karnataka faced systemic ritual discrimination under traditional Brahmanic hierarchies, including practices akin to untouchability that persisted until the 1970s.[4] They were often barred from entering upper-caste temples, accessing public wells, and participating in mainstream social rituals, reinforcing their economic dependence on occupations like toddy tapping.[6] This exclusion stemmed from perceptions of ritual pollution, limiting intergenerational mobility and perpetuating poverty among a population constituting about 18% of the region's demographics.[54] In response, Billavas initiated internal reforms by embracing the egalitarian philosophy of Sri Narayana Guru (1856–1928), a Kerala-born reformer whose teachings emphasized "one caste, one religion, one god" to dismantle hierarchical barriers.[38] Community leaders adopted these principles to advocate temple access and social inclusion, establishing inclusive worship sites such as the Kudroli Gokarnanatheshwara Temple in Mangalore in the early 20th century, which symbolized resistance to exclusionary practices.[4] This self-driven Hinduization involved reinterpreting local possession cults and folklore, like the Koti-Chennaya narrative, to foster pride and unity against historical injustices.[6] Further reforms included leveraging early missionary education from the Basel Mission starting in 1834 to promote literacy and skill development, while forming community associations focused on welfare, education, and entrepreneurship.[38] These organizations, such as Billava trusts, supported the establishment of schools, hospitals, and cultural centers, enabling gradual socio-economic advancement independent of dominant caste patronage.[55] By the mid-20th century, these efforts contributed to reduced overt discrimination, though vestiges persisted in rural areas.[56]Role of Education and Institutions

The Basel Mission, commencing activities in coastal Karnataka in the 1830s, introduced formal education to the Billava community, focusing on literacy, vocational skills, and social emancipation for those facing caste-based exclusion. Schools established by the mission were particularly receptive among Billavas, enabling access to reading, writing, and technical training that facilitated upward mobility beyond traditional occupations like toddy tapping.[57][37][58] In the early 20th century, the philosophical reforms of Sri Narayana Guru (1856–1928), which prioritized education as a means of self-upliftment for marginalized groups, profoundly influenced Billava leaders. Adopting Guru's Vedanta-based teachings, the community constructed temples and adjacent educational facilities to promote literacy and ethical development, countering ritual discrimination while building institutional autonomy. This integration of religious and educational initiatives strengthened communal networks and supported generational access to schooling.[38][59] Community-led institutions further amplified these efforts, with groups like the Sri Venkatesha Shiva Bhakti Yoga Sangha establishing hostels for Billava youth in the mid-20th century to ensure continued education amid economic barriers. Such self-initiated reforms, alongside government reservations for Scheduled Castes, elevated literacy rates and professional diversification, as evidenced by increased participation in governance and entrepreneurship by the 21st century. Ongoing advocacy, including calls for quality schooling in 2024, underscores education's enduring role in addressing internal disparities.[13][60]Key Milestones: Temples and Movements

![Kudroli Gokarnanatheshwara Temple][float-right] In the early 20th century, the Billava community in coastal Karnataka drew inspiration from the teachings of Sree Narayana Guru, a Kerala-based social reformer who advocated spiritual enlightenment and social equality to challenge caste hierarchies.[4][61] This influence prompted Billavas to pursue self-reform, emphasizing education, unity, and access to religious spaces denied to them as a marginalized group previously barred from upper-caste temples.[55][38] A pivotal milestone occurred in 1909 when Narayana Guru consecrated a Shiva temple in Kudroli, Mangalore, dedicated specifically to Billavas and other lower castes, enabling worship without reliance on exclusionary institutions.[61] The temple's foundation was laid around this period, with construction completed by 1912 under the patronage of community leader Adhyaksha Hoige Bazaar Koragappa, marking a deliberate assertion of religious autonomy and dignity.[62][63] Formalized as the Kudroli Gokarnanatheshwara Temple, it embodied principles of inclusivity, allowing unrestricted participation regardless of caste background.[4][64] This initiative spurred broader socio-religious movements among Billavas, including the establishment of additional community temples and cooperative efforts for mutual progress, as urged by Narayana Guru post-construction.[65] These developments represented a non-confrontational path to empowerment, focusing on parallel institutions rather than forced entry into orthodox sites, amid colonial-era dynamics that included missionary influences and local caste resistances.[1] By fostering cultural "Hinduization" and ritual reforms, such as reappropriating possession cults, the community transitioned from untouchability stigma toward social mobility.[65][6]Contemporary Dynamics and Challenges

Political Engagement and Representation

The Billava community, constituting approximately 18% of the population in coastal Karnataka districts such as Dakshina Kannada and Udupi, plays a pivotal role in regional electoral dynamics due to its numerical strength, estimated at around 9 lakh voters in these areas as of 2016.[66][18] This influence stems from organized community forums like the Sri Narayana Guru Vichara Vedike, which mobilizes support for Billava candidates across party lines to enhance representation.[67][68] Historically aligned with the Congress party through leaders like Janardhan Poojary, a former Union minister, the community shifted toward the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the 1990s amid the latter's Hindutva mobilization, providing grassroots support including vigilante activities in Dakshina Kannada.[4] However, persistent grievances over tokenism—such as deployment in street-level enforcement without proportional ticket allocations or cabinet berths—have prompted a partial realignment toward Congress in recent cycles, exemplified by the 2023 assembly polls where Billava voters contributed to Congress gains in coastal seats.[4][69] The BJP's initiatives, including the establishment of the Sri Narayana Guru Development Board in February 2023 for Billava and allied castes' welfare, aimed to retain loyalty but have been critiqued as inadequate amid demands for dedicated political quotas.[7] Prominent Billava politicians include B.K. Hariprasad, a Congress Rajya Sabha member who emerged as a leading community figure by 2023, advocating for inclusion in the Karnataka cabinet under the Congress government.[70][71] Other notables are Sunil Kumar, Dakshina Kannada's district in-charge minister, and Padmaraj R. Poojary, fielded by Congress in the 2024 Lok Sabha elections from the same constituency.[18][4] In the 2023 Karnataka assembly, Congress nominated at least two Billavas/Eedigas, including Geetha Shivarajkumar, reflecting targeted outreach.[4] Representation remains contested, with community seers in 2023 decrying a "use-and-throw" approach by parties and demanding three assembly seats each for Billava, Namdhari, and Eediga subgroups.[72] In the Congress-led Karnataka government formed in May 2023, Billavas secured positions within the Other Backward Classes (OBC) quota, including ministerial roles alongside castes like Kuruba and Besta, underscoring caste arithmetic in cabinet formation.[73] Yet, broader underrepresentation persists, as evidenced by the BJP's failure to field Billava candidates in key 2024 parliamentary seats despite prior welfare measures like the Billava Development Corporation established pre-2023 elections.[74] Community leaders continue pushing for distinct census enumeration as "Billava" to bolster reservation claims and electoral leverage.[75] This engagement reflects pragmatic caste-based bargaining rather than ideological purity, with forums prioritizing intra-community advancement over party loyalty.[67]Achievements in Mobility and Contributions

The Billava community has achieved significant social mobility by leveraging philosophical reforms inspired by Sri Narayana Guru, enabling upliftment from historical marginalization despite ongoing conflicts with dominant castes.[39] [5] This transition involved adopting Guru's Vedanta teachings to challenge caste restrictions and secure temple access, fostering internal solidarity and upward movement from traditional roles in toddy tapping and martial arts.[38] Access to missionary education from the 1830s onward proved crucial, equipping converts with skills that facilitated escape from economic vulnerability and entry into diverse professions.[57] Self-initiated institutions played a pivotal role in this progress, including the establishment of schools, cooperative societies for economic self-reliance, and temples that symbolized reclaimed religious agency.[37] These efforts have led to widespread migration for employment, particularly to Gulf countries, where community members have achieved stable livelihoods and remittances supporting further development.[8] By the late 20th century, such initiatives contributed to a shift toward thriving status, with increased representation in urban jobs, business ventures, and public service.[37] In contributions to broader society, Billavas have constructed landmark sites like the Gokarnanatheshwara Temple in Mangalore, completed in 1910, which serves as a major worship center and emblem of community resilience.[76] Their involvement in education includes founding institutions that extend beyond the community, while in politics, figures such as B.K. Hariprasad have risen to prominent roles, including as a Rajya Sabha member, advocating for regional interests.[70] [76] Economically, cooperative models and entrepreneurial successes, such as in hospitality and trade, have bolstered local economies in coastal Karnataka.[76] Additionally, traditional knowledge in Ayurveda and medicinal plant collection has informed regional health practices, though largely undocumented in formal records.[8]Ongoing Debates: Identity, Reservations, and Internal Critiques

Community leaders within the Billava population have emphasized the importance of self-identifying as "Billava" in caste censuses to ensure accurate enumeration and safeguard access to reservation quotas, particularly amid ongoing surveys in Karnataka as of August 2025. This push stems from concerns that vague or alternative entries could dilute demographic visibility, potentially undermining political representation and welfare allocations for the group, which constitutes a significant portion of coastal Karnataka's Scheduled Caste population. Such advocacy reflects broader tensions over preserving distinct ethnic and cultural markers, including historical claims to indigenous or "Adinivasi" origins predating Dravidian or Aryan migrations, as articulated in community narratives tracing Billava roots to ancient Tulunadu inhabitants.[77][75][29] Debates on reservations intensify around sub-categorization within Karnataka's Scheduled Caste framework, where Billavas fall under Category II-A, a grouping perceived by some as less disadvantaged compared to Category I communities. In January 2023, Billava representatives joined padayatras protesting potential reallocations under sub-categorization proposals, arguing that redistributing the 15% SC quota could disproportionately reduce opportunities for II-A groups despite their historical exclusion and ongoing socio-economic gaps. Critics from more backward SC subgroups contend that Billavas' relative progress in education and land ownership—evidenced by higher literacy rates and urban migration—necessitates equitable intra-SC adjustments to prevent dominant castes from monopolizing benefits, a position bolstered by empirical data from state backward classes commissions showing uneven benefit distribution.[78][79] A parallel controversy involves Billava Christians and reservation eligibility, fueled by Karnataka's 2025 caste census drafts listing Christian sub-castes, including Billava variants, under Hindu-origin categories. This has sparked backlash, as the state's anti-conversion law bars reservation benefits for religious converts, yet inclusions raise fears of circumventing quotas by retaining caste labels post-conversion, potentially straining Hindu SC allocations. Proponents of strict enforcement argue that empirical conversion trends—driven by evangelism in coastal regions—erode the affirmative action's intent to uplift historically oppressed Hindu groups, while community advocates highlight economic vulnerabilities among converts ineligible for SC status.[80][81][82] Internal critiques within the Billava community often center on leadership fragmentation and identity dilution, with some attributing diminished political clout to erosion of unified cultural markers like matrilineal inheritance (Aliya Santana) and spirit worship practices amid modernization. Analyses from 2025 point to intra-community disparities, where upwardly mobile subgroups leverage religious conversions—such as to Buddhism—for social ascent, yet this fosters critiques of abandoning ancestral Bhuta Kola traditions, contributing to youth disaffection and localized violence in Dakshina Kannada. Economic critiques highlight a "creamy layer" effect, where affluent Billavas dominate reservation slots, prompting calls for internal merit-based reforms over perpetual quota reliance, though data from community surveys indicate persistent rural poverty rates exceeding 20% as of recent state reports.[83][65][84]Related Communities and Comparative Context

Similar Groups in South India

The Billava, primarily known for toddy tapping in coastal Karnataka, exhibit parallels with the Idiga (also termed Ediga or Goud in certain regions) of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, and parts of Karnataka, who similarly derived livelihoods from palm toddy extraction and related agricultural pursuits. Both groups historically navigated ritual pollution perceptions tied to their occupations, prompting organized efforts for social elevation, including federations uniting toddy-tapper castes for economic and cultural advocacy as documented in regional conferences.[85][86] In 2023, joint padayatras by Namadhari, Billava, and Idiga subgroups underscored shared demands for recognizing toddy-related trades amid regulatory shifts.[78] In Kerala, the Ezhava (also Thiyya or Tiyyar) community mirrors the Billava in ancestral roles as toddy tappers, martial practitioners, and Ayurvedic healers, with both exhibiting ethnic and occupational overlaps that fueled parallel reformist drives against caste hierarchies. Sree Narayana Guru's 19th-20th century initiatives among Ezhavas, emphasizing temple access and education, parallel Billava-led movements like those inspired by similar philosophies of self-reliance in coastal Karnataka.[87][88] These affinities extend to spirit worship traditions and transitions from warrior-hunter backgrounds to settled agrarian roles, though Ezhavas achieved broader political mobilization through organizations like the SNDP Yogam by the early 1900s.[89] The Nadar (including Shanar subgroups) of Tamil Nadu share toddy-tapping heritage with Billavas, particularly in southern districts where Shanars focused on palmyra extraction, leading to comparable 19th-century agitations for upward mobility via trade diversification and Christian conversions among subsets. Unlike Billavas' retention of indigenous Bhuta Kola rituals, Nadars integrated Vaishnava elements while contesting exclusion from public spaces, culminating in temple entry victories by the 1940s.[90] Across these groups, empirical patterns reveal causal links between occupational stigmatization and proactive reforms, with population sizes—Ezhavas at around 23% of Kerala's Hindus by 1931 censuses and Nadars forming significant blocs in Tamil Nadu—enabling collective bargaining absent in smaller castes.[3]Distinctions from Neighboring Castes

The Billava caste differs from neighboring communities in Tulu Nadu, such as the Bunt and Mogaveera, foremost in traditional occupation, with Billavas specializing in toddy tapping by climbing palm trees to extract sap for fermentation and distillation, a labor-intensive role tied to coastal agrarian economies.[91] In contrast, Bunts historically served as landowners and warriors managing estates, while Mogaveeras focused on marine fishing and coastal trade.[92][3] Socially, Billavas occupied a lower rung in the local hierarchy, enduring practices akin to untouchability from higher-status groups like Bunts, who claimed martial and landowning privileges, though not formally Brahminical.[35] This stemmed from associations with alcohol production, deemed impure, unlike the agrarian purity attributed to Bunts or the seafaring identity of Mogaveeras, both endogamous but with greater ritual access in shared Bhuta Kola spirit worship traditions.[6] Post-independence classifications reflect this: Billavas as Scheduled Castes eligible for affirmative action, while Bunts and Mogaveeras fall under Other Backward Classes with less extensive reservations.[35] Culturally, Billavas maintain distinct folklore, including epics of folk heroes Koti and Chennaya symbolizing resistance against Bunt overlords, underscoring historical tensions over land and autonomy not central to other castes' narratives.[35] All groups share Tuluva matrilineal inheritance (aliyasantana) and spirit veneration, yet Billavas uniquely reformed possession cults under 19th-century missionary influences, blending Christian education with indigenous practices, diverging from the more secular landowning ethos of Bunts.[6] These distinctions persist amid modernization, with Billavas showing higher mobility via education but retaining occupational stereotypes.[3]References