Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Biofilter

View on Wikipedia

Biofiltration is a pollution control technique using a bioreactor containing living material to capture and biologically degrade pollutants. Common uses include processing waste water, capturing harmful chemicals or silt from surface runoff, and microbiotic oxidation of contaminants in air. Industrial biofiltration can be classified as the process of utilizing biological oxidation to remove volatile organic compounds, odors, and hydrocarbons.

Examples of biofiltration

[edit]Examples of biofiltration include:

Control of air pollution

[edit]When applied to air filtration and purification, biofilters use microorganisms to remove air pollution.[1] The air flows through a packed bed and the pollutant transfers into a thin biofilm on the surface of the packing material. Microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi are immobilized in the biofilm and degrade the pollutant. Trickling filters and bioscrubbers rely on a biofilm and the bacterial action in their recirculating waters.

The technology finds the greatest application in treating malodorous compounds and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Industries employing the technology include food and animal products, off-gas from wastewater treatment facilities, pharmaceuticals, wood products manufacturing, paint and coatings application and manufacturing and resin manufacturing and application, etc. Compounds treated are typically mixed VOCs and various sulfur compounds, including hydrogen sulfide. Very large airflows may be treated and although a large area (footprint) has typically been required—a large biofilter (>200,000 acfm) may occupy as much or more land than a football field—this has been one of the principal drawbacks of the technology. Since the early 1990s, engineered biofilters have provided significant footprint reductions over the conventional flat-bed, organic media type.

One of the main challenges to optimum biofilter operation is maintaining proper moisture throughout the system. The air is normally humidified before it enters the bed with a watering (spray) system, humidification chamber, bio scrubber, or bio trickling filter. Properly maintained, a natural, organic packing media like peat, vegetable mulch, bark or wood chips may last for several years but engineered, combined natural organic, and synthetic component packing materials will generally last much longer, up to 10 years. Several companies offer these types of proprietary packing materials and multi-year guarantees, not usually provided with a conventional compost or wood chip bed biofilter.

Although widely employed, the scientific community is still unsure of the physical phenomena underpinning biofilter operation, and information about the microorganisms involved continues to be developed.[2] A biofilter/bio-oxidation system is a fairly simple device to construct and operate and offers a cost-effective solution provided the pollutant is biodegradable within a moderate time frame (increasing residence time = increased size and capital costs), at reasonable concentrations (and lb/hr loading rates) and that the airstream is at an organism-viable temperature. For large volumes of air, a biofilter may be the only cost-effective solution. There is no secondary pollution (unlike the case of incineration where additional CO2 and NOx are produced from burning fuels) and degradation products form additional biomass, carbon dioxide and water. Media irrigation water, although many systems recycle part of it to reduce operating costs, has a moderately high biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and may require treatment before disposal. However, this "blowdown water", necessary for proper maintenance of any bio-oxidation system, is generally accepted by municipal publicly owned treatment works without any pretreatment.

Biofilters are being utilized in Columbia Falls, Montana at Plum Creek Timber Company's fiberboard plant.[3] The biofilters decrease the pollution emitted by the manufacturing process and the exhaust emitted is 98% clean. The newest, and largest, biofilter addition to Plum Creek cost $9.5 million, yet even though this new technology is expensive, in the long run it will cost less overtime than the alternative exhaust-cleaning incinerators fueled by natural gas (which are not as environmentally friendly).

Water treatment

[edit]

Biofiltration was first introduced in England in 1893 as a trickling filter for wastewater treatment and has since been successfully used for the treatment of different types of water.[5] Biological treatment has been used in Europe to filter surface water for drinking purposes since the early 1900s and is now receiving more interest worldwide. Biofiltration is also common in wastewater treatment, aquaculture and greywater recycling, as a way to minimize water replacement while increasing water quality.

Biofiltration process

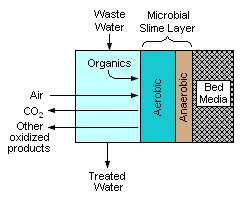

[edit]A biofilter is a bed of media on which microorganisms attach and grow to form a biological layer called biofilm. Biofiltration is thus usually referred to as a fixed–film process. Generally, the biofilm is formed by a community of different microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, yeast, etc.), macro-organisms (protozoa, worms, insect's larvae, etc.) and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) (Flemming and Wingender, 2010). Air or water flows through a media bed and any suspended compounds are transferred into a surface biofilm where microorganisms are held to degrade pollutants. The aspect of the biofilm[6] is usually slimy and muddy.

Water to be treated can be applied intermittently or continuously over the media, via upflow or downflow. Typically, a biofilter has two or three phases, depending on the feeding strategy (percolating or submerged biofilter):

- a solid phase (media)

- a liquid phase (water);

- a gaseous phase (air).

Organic matter and other water components diffuse into the biofilm where the treatment occurs, mostly by biodegradation. Biofiltration processes are usually aerobic, which means that microorganisms require oxygen for their metabolism. Oxygen can be supplied to the biofilm, either concurrently or countercurrently with water flow. Aeration occurs passively by the natural flow of air through the process (three phase biofilter) or by forced air supplied by blowers.

Microorganisms' activity is a key-factor of the process performance. The main influencing factors are the water composition, the biofilter hydraulic loading, the type of media, the feeding strategy (percolation or submerged media), the age of the biofilm, temperature, aeration, etc.

The mechanisms by which certain microorganisms can attach and colonize on the surface of filter media of a biofilter can be via transportation, initial adhesion, firm attachment, and colonization [Van Loosdrecht et al., 1990]. The transportation of microorganisms to the surface of the filter media is further controlled by four main processes of diffusion (Brownian motion), convection, sedimentation, and active mobility of the microorganisms. The overall filtration process consists of microorganism attachment, substrate utilization which causes biomass growth, to biomass detachment.[5]

Types of filtering media

[edit]Most biofilters use media such as sand, crushed rock, river gravel, or some form of plastic or ceramic material shaped as small beads and rings.[7]

Advantages

[edit]Although biological filters have simple superficial structures, their internal hydrodynamics and the microorganisms' biology and ecology are complex and variable.[8] These characteristics confer robustness to the process. In other words, the process has the capacity to maintain its performance or rapidly return to initial levels following a period of no flow, of intense use, toxic shocks, media backwash (high rate biofiltration processes), etc.

The structure of the biofilm protects microorganisms from difficult environmental conditions and retains the biomass inside the process, even when conditions are not optimal for its growth. Biofiltration processes offer the following advantages: (Rittmann et al., 1988):

- Since microorganisms are retained within the biofilm, biofiltration allows the development of microorganisms with relatively low specific growth rates;

- Biofilters are less subject to variable or intermittent loading and to hydraulic shock;[9]

- Operational costs are usually lower than for activated sludge;

- The final treatment result is less influenced by biomass separation since the biomass concentration at the effluent is much lower than for suspended biomass processes;

- The attached biomass becomes more specialized (higher concentration of relevant organisms) at a given point in the process train because there is no biomass return.[10]

Drawbacks

[edit]Because filtration and growth of biomass leads to an accumulation of matter in the filtering media, this type of fixed-film process is subject to bioclogging and flow channeling. Depending on the type of application and on the media used for microbial growth, bioclogging can be controlled using physical and/or chemical methods. Backwash steps can be implemented using air and/or water to disrupt the biomat and recover flow whenever possible. Chemicals such as oxidizing (peroxide, ozone) or biocide agents can also be used.

Biofiltration can require a large area for some treatment techniques (suspended growth and attached growth processes) as well as long hydraulic retention times (anaerobic lagoon and anaerobic baffled reactor).[11]

Drinking water

[edit]For drinking water, biological water treatment involves the use of naturally occurring microorganisms in the surface water to improve water quality. Under optimum conditions, including relatively low turbidity and high oxygen content, the organisms break down material in the water and thus improve water quality. Slow sand filters or carbon filters are used to provide a support on which these microorganisms grow. These biological treatment systems effectively reduce water-borne diseases, dissolved organic carbon, turbidity and color in surface water, thus improving overall water quality.

Typically in drinking water treatment; granular activated carbon or sand filters are used to prevent re-growth of microorganisms in water distribution pipes by reducing levels of iron and nitrate that act as a microbial nutrient. GAC also reduces chlorine demand and other disinfection by-product accumulation by acting as a first line of disinfection. Bacteria attached to filter media as a biofilm oxidize organic material as both an energy and carbon source, this prevents undesired bacteria from using these sources which can reduce water odors and tastes [Bouwer, 1998]. These biological treatment systems effectively reduce water-borne diseases, dissolved organic carbon, turbidity and color in surface water, thus improving overall water quality.

Biotechnological techniques can be used to improve the biofiltration of drinking water by studying the microbial communities in the water. Such techniques include qPCR (quantitative polymerase chain reaction), ATP assay, metagenomics, and flow cytometry.[12]

Wastewater

[edit]Biofiltration is used to treat wastewater from a wide range of sources, with varying organic compositions and concentrations. Many examples of biofiltration applications are described in the literature. Bespoke biofilters have been developed and commercialized for the treatment of animal wastes,[13] landfill leachates,[14] dairy wastewater,[15] domestic wastewater.[16]

This process is versatile as it can be adapted to small flows (< 1 m3/d), such as onsite sewage[17] as well as to flows generated by a municipality (> 240 000 m3/d).[18] For decentralized domestic wastewater production, such as for isolated dwellings, it has been demonstrated that there are important daily, weekly and yearly fluctuations of hydraulic and organic production rates related to modern families' lifestyle.[19] In this context, a biofilter located after a septic tank constitutes a robust process able to sustain the variability observed without compromising the treatment performance.

In anaerobic wastewater treatment facilities, biogas is fed through a bio-scrubber and “scrubbed” with activated sludge liquid from an aeration tank.[20] Most commonly found in wastewater treatment is the trickling filter process (TFs) [Chaudhary, 2003]. Trickling filters are an aerobic treatment that uses microorganisms on attached medium to remove organic matter from wastewater.

In primary wastewater treatment, biofiltration is used to control levels of biochemical oxygen, demand, chemical oxygen demand, and suspended solids. In tertiary treatment processes, biofiltration is used to control levels of organic carbon [ Carlson, 1998].

Use in aquaculture

[edit]The use of biofilters is common in closed aquaculture systems, such as recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS). The biofiltration techniques used in aquaculture can be separated into three categories: biological, physical, and chemical. The primary biological method is nitrification; physical methods include mechanical techniques and sedimentation, and chemical methods are usually used in tandem with one of the other methods.[21] Some farms use seaweed, such as those from the genera Ulva, to take excess nutrients out of the water and release oxygen into the ecosystem in a “recirculation system” while also serving as a source of income when they sell the seaweed for safe human consumption.[22]

Many designs are used, with different benefits and drawbacks, however the function is the same: reducing water exchanges by converting ammonia to nitrate. Ammonia (NH4+ and NH3) originates from the brachial excretion from the gills of aquatic animals and from the decomposition of organic matter. As ammonia-N is highly toxic, this is converted to a less toxic form of nitrite (by Nitrosomonas sp.) and then to an even less toxic form of nitrate (by Nitrobacter sp.). This "nitrification" process requires oxygen (aerobic conditions), without which the biofilter can crash. Furthermore, as this nitrification cycle produces H+, the pH can decrease, which necessitates the use of buffers such as lime.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Joseph S. Devinny; Marc A. Deshusses & Todd S. Webster (1999). Biofiltration for Air Pollution Control. Lewis Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56670-289-8.

- ^ Cruz-García, Blanca; Geronimo-Meza, Andrea Selene; Martínez-Lievana, Concepción; Arriaga, Sonia; Huante-González, Yolanda; Aizpuru, Aitor (2019). "Biofiltration of high concentrations of methanol vapors: removal performance, carbon balance and microbial and fly populations". Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology. 94 (6): 1925–1936. Bibcode:2019JCTB...94.1925C. doi:10.1002/jctb.5974. ISSN 0268-2575. S2CID 104375950.

- ^ Lynch, Keriann (2008-10-26). "'Bug farm' a breath of fresh air". Spokesman Review.

- ^ Beychok, Milton R. (1967). Aqueous Wastes from Petroleum and Petrochemical Plants (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. LCCN 67019834.

- ^ a b Chaudhary, Durgananda Singh; Vigneswaran, Saravanamuthu; Ngo, Huu-Hao; Shim, Wang Geun; Moon, Hee (November 2003). "Biofilter in water and wastewater treatment". Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering. 20 (6): 1054–1065. doi:10.1007/BF02706936. S2CID 10028364.

- ^ H.C. Flemming & J. Wingender (2010). "The biofilm matrix". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 8 (9): 623–633. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2415. PMID 20676145. S2CID 28850938.

- ^ Ebeling, James. "Biofiltration-Nitrification Design Overview" (PDF). Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ C.R. Curds & H.A. Hawkes (1983). Ecological Aspects of Used-Water Treatment. The Processes and their Ecology Vol.3. ISBN 9780121995027.

- ^ P.W. Westerman; J.R. Bicudo & A. Kantardjieff (1998). Aerobic fixed-media biofilter treatment of flushed swine manure. ASAE Annual International Meeting - Florida. Archived from the original on 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2013-06-19.

- ^ H. Odegaard (2006). "Innovations in wastewater treatment: the moving bed biofilm process". Water Science and Technology. 53 (9): 17–33. Bibcode:2006WSTec..53...17O. doi:10.2166/wst.2006.284. PMID 16841724. Archived from the original on 2013-10-18. Retrieved 2013-06-19.

- ^ Ali Musa, Mohammed; Idrus, Syazwani (2021). "Physical and Biological Treatment Technologies of Slaughterhouse Wastewater: A Review". Sustainability. 13 (9): 4656. Bibcode:2021Sust...13.4656M. doi:10.3390/su13094656.

- ^ Kirisits, Mary Jo; Emelko, Monica B.; Pinto, Ameet J. (June 2019). "Applying biotechnology for drinking water biofiltration: advancing science and practice". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 57: 197–204. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2019.05.009. PMID 31207464.

- ^ G. Buelna, R. Dubé & N. Turgeon (2008). "Pig manure treatment by organic bed biofiltration". Desalination. 231 (1–3): 297–304. Bibcode:2008Desal.231..297B. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2007.11.049.

- ^ M. Heavey (2003). "Low-cost treatment of landfill leachate using peat". Waste Management. 23 (5): 447–454. Bibcode:2003WaMan..23..447H. doi:10.1016/S0956-053X(03)00064-3. PMID 12893018.

- ^ M.G. Healy; M. Rodgers & J. Mulqueen (2007). "Treatment of dairy wastewater using constructed wetlands and intermittent sand filters". Bioresource Technology. 98 (12): 2268–2281. Bibcode:2007BiTec..98.2268H. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2006.07.036. hdl:10379/2567. PMID 16973357.

- ^ Jowett, E. Craig; McMaster, Michaye L. (January 1995). "On-Site Wastewater Treatment Using Unsaturated Absorbent Biofilters". Journal of Environmental Quality. 24 (1): 86–95. Bibcode:1995JEnvQ..24...86J. doi:10.2134/jeq1995.00472425002400010012x.

- ^ Talbot P, Bélanger G, Pelletier M, Laliberté G, Arcand Y (1996). "Development of a biofilter using an organic medium for on-site wastewater treatment". Water Science and Technology. 34 (3–4). doi:10.1016/0273-1223(96)00609-9.

- ^ Y. Bihan & P. Lessard (2000). "Use of enzyme tests to monitor the biomass activity of a trickling biofilter treating domestic wastewaters". Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology. 75 (11): 1031–1039. Bibcode:2000JCTB...75.1031B. doi:10.1002/1097-4660(200011)75:11<1031::AID-JCTB312>3.0.CO;2-A.

- ^ R. Lacasse (2009). Effectiveness of domestic wastewater treatment technologies in the context of the new constrains imposed by lifestyle changes in north American families (PDF). NOWRA - 18th Annual Technical Education Conference and Expo in Milwaukee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-18. Retrieved 2013-06-19.

- ^ "Removal of hydrogen sulfide from an anaerobic biogas using a bio-scrubber". Water Science and Technology. 36 (6–7). 1997. doi:10.1016/S0273-1223(97)00542-8.

- ^ Crab, Roselien; Avnimelech, Yoram; Defoirdt, Tom; Bossier, Peter; Verstraete, Willy (September 2007). "Nitrogen removal techniques in aquaculture for a sustainable production" (PDF). Aquaculture. 270 (1–4): 1–14. Bibcode:2007Aquac.270....1C. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2007.05.006.

- ^ Neori, Amir; Chopin, Thierry; Troell, Max; Buschmann, Alejandro H.; Kraemer, George P.; Halling, Christina; Shpigel, Muki; Yarish, Charles (March 2004). "Integrated aquaculture: rationale, evolution and state of the art emphasizing seaweed biofiltration in modern mariculture". Aquaculture. 231 (1–4): 361–391. Bibcode:2004Aquac.231..361N. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2003.11.015.

Further reading

[edit]- Biofilter Bags SE-14. (2012). California Stormwater BMP Handbook, 1–3. Retrieved from https://www.cityofventura.ca.gov/DocumentCenter/View/13163/CASQA-Guidance-SE-14-Biofilter-Bags.

- Bouwer, Edward J.; Crowe, Patricia B. (September 1988). "Biological Processes in Drinking Water Treatment". Journal AWWA. 80 (9): 82–93. Bibcode:1988JAWWA..80i..82B. doi:10.1002/j.1551-8833.1988.tb03103.x. JSTOR 41292287.

- Chaudhary, Durgananda Singh; Vigneswaran, Saravanamuthu; Ngo, Huu-Hao; Shim, Wang Geun; Moon, Hee (November 2003). "Biofilter in water and wastewater treatment". Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering. 20 (6): 1054–1065. doi:10.1007/BF02706936. S2CID 10028364.

- Carlson, Kenneth H.; Amy, Gary L. (December 1998). "BOM removal during biofiltration". Journal AWWA. 90 (12): 42–52. Bibcode:1998JAWWA..90l..42C. doi:10.1002/j.1551-8833.1998.tb08550.x. JSTOR 41296445. S2CID 91347325.

- Pagans, Estel.la; Font, Xavier; Sánchez, Antoni (October 2005). "Biofiltration for ammonia removal from composting exhaust gases". Chemical Engineering Journal. 113 (2–3): 105–110. Bibcode:2005ChEnJ.113..105P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.470.1234. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2005.03.004.

- Nishimura, Sosuke; Yoda, Motoyuki (1 January 1997). "Removal of hydrogen sulfide from an anaerobic biogas using a bio-scrubber". Water Science and Technology. 36 (6): 349–356. doi:10.1016/S0273-1223(97)00542-8.

- van Loosdrecht, M C; Lyklema, J; Norde, W; Zehnder, A J (March 1990). "Influence of interfaces on microbial activity". Microbiological Reviews. 54 (1): 75–87. doi:10.1128/mr.54.1.75-87.1990. PMC 372760. PMID 2181260.

External links

[edit]- Bioswales and strips for storm runoff - California Dept. of Transportation (CalTrans)