Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

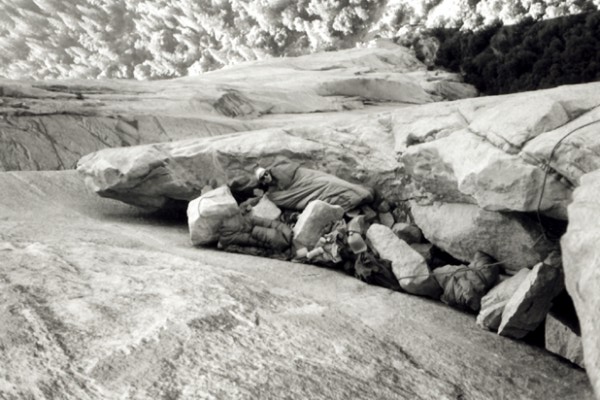

Bivouac shelter

View on Wikipedia

A bivouac shelter or bivvy (alternately bivy, bivi, bivvi) is any of a variety of improvised camp site or shelter that is usually of a temporary nature, used especially by soldiers or people engaged in backpacking, bikepacking, scouting or mountain climbing.[1] It may often refer to sleeping in the open with a bivouac sack, but it may also refer to a shelter constructed of natural materials like a structure of branches to form a frame, which is then covered with leaves, ferns and similar material for waterproofing and duff (leaf litter) for insulation. Modern bivouacs often involve the use of one- or two-person tents but may also be without tents or full cover.[2] In modern mountaineering the nature of the bivouac shelter will depend on the level of preparedness, in particular whether existing camping and outdoor gear may be incorporated into the shelter.[3]

Etymology

[edit]The word bivouac is French and ultimately derives from an 18th-century Swiss German usage of Beiwacht (bei by, Wacht watch or patrol).[2] It referred to an additional watch that would be maintained by a military or civilian force to increase vigilance at an encampment.[2] Following use by the troops of the British Empire the term became also known as bivvy for short.[2]

Construction

[edit]

Artificial bivouacs can be constructed using a variety of available materials from corrugated iron sheeting or plywood, to groundsheets or a purpose-made basha. Although these have the advantage of being speedy to erect and resource-efficient, they have relatively poor insulation properties.

There are many different ways to put up a bivouac shelter. The most common method is to use one bivouac sheet as the roof of the shelter and a second as the groundsheet. The 'roof' flysheet is suspended along its ridge line by a cord tied between two trees which are a suitable distance apart. The four corners of the flysheet are then either pegged out or tied down to other trees. Care must be taken to leave a gap between the ground and the sheet to ensure that there is enough air flow to stop condensation.

A basha is a simple tent, made from one or two sheets of waterproof fabric and some strong cord. Generally a basha is made of reinforced nylon with eyelets and loops or tabs located along all four sides of the sheet and sometimes across the two central lines of symmetry. The basha is an extremely versatile shelter that can be erected in many different ways to suit the particular conditions of the location. (The word also sometimes refers to a special type of bivouac sack described below).[4]

Bivouac sack

[edit]

A bivouac sack is a smaller type of bivouac shelter. Generally it is a portable, lightweight, waterproof shelter, and an alternative to larger bivouac shelters. The main benefit of a bivouac sack shelter is speed of setup and ability to use in a tiny space as compared to tent-like shelters. A bivouac sack is therefore a common choice for hikers, cyclists or climbers who have to camp in tight areas, or in unknown areas. A bivouac sack will usually have a thin waterproof fabric shell that is designed to slip over a sleeping bag, providing an additional 5 to 10 °C of insulation and forming an effective barrier against wind chill and rain.[5]

A drawback of a simple bivouac sack is the humidity that condenses on the inner side, leaving the occupant or the sleeping bag moist. Moisture severely decreases the insulating effect of sleeping bags.[6] This problem has been alleviated somewhat in recent years with the advent of more waterproof, but breathable fabrics, such as Gore-Tex, which allow some humidity to pass through the fabric while blocking most external water. A traditional bivouac bag typically cinches all the way down to the user's face, leaving only a small hole to breathe or look through. Other bivouac sacks have a mesh screen at the face area to allow for outside visibility and airflow, while still protecting from insects.

Since the 1980s, an increasing number of militaries including those of the US, UK and many European countries include bivouac sacks as part of their standard issue travelling sleep systems. These frequently are designed to attach to the same military's standard issue sleeping bags, and allow soldiers on expedition or away from base camp to keep their entire sleep kit in one individual and low profile system.[7]

Boofen

[edit]In the German region of Saxon Switzerland in the Elbe Sandstone Mountains, climbers refer to overnighting in the open air as Boofen (pronounced "bo-fen").[8] The spot selected for overnight stays usually comprises an overhang in the sandstone rock or a cave, the so-called Boofe ("bo-fe"). This has often been adapted with a sleeping area and fireplace. In the national park itself, Boofen is only permitted at designated sites and only in connection with climbing, although in this case lighting fires is absolutely forbidden. The colloquial Saxon word boofen is a cognate of pofen (to sleep soundly and for a long time).

Examples

[edit]Count Henry Russell-Killough, the "hermit of the Pyrenees", is broadly accredited with the invention of the bivouac in extreme, inhospitable places. He would bivouac in the open, creating a blanket of rocks and earth or using a simple bag.[9]

An example of a bivouac being made in a time of urgency was shown when the climber Hermann Buhl made his ascent of Nanga Parbat in 1953 and was forced to bivouac alone on a rock ledge at 8,000 metres (26,000 ft) altitude, in order to survive until the following morning.[10]

Modern bivouacs have evolved to offer heightened levels of comfort for climbers and explorers. Modern portaledges (the vertical camping version of a tent) are a more comfortable, safer, and sturdier option to hanging hammocks.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Bivouac". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on September 25, 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d Bradford, James (2004). International Encyclopedia of Military History. Routledge.

- ^ Houston, Mark (2004). Alpine Climbing: Techniques to Take You Higher. The Mountaineers Books.

- ^ "How to build a basha". timeoff2outdoors.com. Retrieved 2020-10-05.

- ^ Howe, Steve; Getchell, Dave (March 1995). "Hit the sack". Backpacker. Vol. 23, no. 139. pp. 143–169. ISSN 0277-867X. Retrieved 2013-06-21.

- ^ Camenzind, M; Weder, M; Den Hartog, E (2002). "Influence of Body Moisture on the Thermal Insulation of Sleeping Bags". Blowing Hot and Cold: Protecting Against Climatic Extremes, Papers Presented at the RTO Human Factors and Medicine Panel (HFM) Symposium Held in Dresden, Germany, 8-10 October 2001. North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Research and Technology Organization. ISBN 978-92-837-1082-0. S2CID 26357620. DTIC ADA403853.

- ^ "Sleep Systems". Program Executive Office Soldier. Retrieved 17 October 2025.

- ^ "Where to find free, legal bivouac & camp sites in Europe". Caravanistan. 2020-09-26. Retrieved 2020-10-05.

- ^ "Become an FT subscriber to read | Financial Times". Financial Times. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

- ^ "9 Legendary Bivoacs". Adventure Journal. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ^ "Big Wall Vertical Camping: How Does It Really Work?". The Dyrt Magazine. 2019-05-15. Retrieved 2021-09-07.

Bivouac shelter

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Etymology

Definition

A bivouac shelter, often shortened to bivouac or bivy, is an improvised, temporary encampment or overnight stay used primarily in remote or harsh environments such as mountains or wilderness areas, typically without the use of a full tent.[10] It serves as a minimalist form of protection for resting, emphasizing rapid setup and breakdown to suit situations where time, weight, or terrain constraints limit more structured options.[11] Key characteristics of a bivouac shelter include its lightweight construction, portability, and reliance on natural elements, tarps, or basic gear like sleeping bags and groundsheets, allowing for quick assembly in many cases. Unlike a full tent, which features rigid poles, sewn-in floors, and enclosed fabric walls for comprehensive weatherproofing, a bivouac often involves sleeping in the open or under minimal covering, such as a waterproof sack or improvised windbreak.[3] This setup prioritizes mobility over comfort, making it suitable for high-altitude or multi-day expeditions where carrying extra equipment is impractical.[12] In modern contexts as of 2025, bivouac shelters have gained popularity in ultralight backpacking and emergency preparedness, where enthusiasts use compact bivy sacks or tarps to reduce pack weight to under 2 pounds while maintaining essential protection against rain, wind, and insects.[13] These applications extend to recreational hiking in protected areas and survival training, adapting traditional military and climbing practices to emphasize sustainability and minimal environmental impact.[11]Etymology

The term "bivouac" entered the French language in the 17th century as "bivouac," denoting a temporary military encampment, and ultimately derives from the Swiss German "Biwwak" or "Beiwacht," which translates to "auxiliary guard" or "night watch," referring to additional sentries posted during the night.[4] This Swiss German root, from the Alemannic dialect spoken in regions like Switzerland and Alsace, reflects the practice of soldiers maintaining vigilance without full shelter, a concept that spread through European military usage during conflicts such as the Thirty Years' War.[14] The word was adopted into English around the 1700s, primarily through French military terminology, initially describing an armed night encampment without tents, as documented in early 18th-century texts on warfare.[15] Over time, "bivouac" evolved into a verb meaning to lodge temporarily in the open or with minimal cover, emphasizing impromptu camping.[7] In British English, informal variants such as "bivy," "bivi," or "bivvi" emerged in the early 20th century, particularly during World War I, as slang shortenings for a temporary shelter or the act of bivouacking, often used in outdoor and military contexts.[16] Culturally, the term has been adapted in other languages for similar improvised setups; in German, "Biwak" (or historically "Biwwak") retains the original sense of a field encampment or guard post, borrowed back from French but rooted in the same Germanic etymology.[17]Historical Development

Military Origins

The term bivouac originated in late 17th- or early 18th-century European military practice during the Thirty Years' War, referring to a temporary night encampment without tents, designed to facilitate rapid movement and maintain tactical flexibility during campaigns. Derived from the Swiss German "Beiwacht," meaning an additional guard or patrol duty, it entered French military lexicon around the early 1700s and spread across armies as a means for soldiers to rest in the open while remaining armed and alert for security. This approach contrasted with formal tented camps, reducing the logistical strain of transporting heavy equipment and allowing forces to cover greater distances without delay.[7][18] During the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), bivouacs became a hallmark of fast-paced warfare, particularly in Napoleon's Grande Armée, where soldiers often slept under the stars or used greatcoats for cover to prioritize speed over comfort. Armies like the French emphasized these open-air halts to execute swift maneuvers, such as the rapid advances across Europe that outpaced slower coalition forces burdened by full encampments. Bivouacs were typically set up after dusk for concealment and included basic precautions like posted sentries, associating the practice closely with "night watches" to deter surprise attacks. This method minimized supply demands, enabling armies of tens of thousands to sustain momentum in grueling campaigns without the encumbrance of tentage. For example, after the first day of the Battle of Wagram on 5 July 1809, French troops established a bivouac to rest before the decisive engagement the next day.[19] In the 20th century, bivouac practices evolved with industrialized warfare. During World War I, soldiers frequently bivouacked in dug-in foxholes and improvised positions along trench lines, providing essential cover from artillery while allowing quick redeployment during offensives. World War II saw further adaptation, with troops using ponchos or shelter halves to form lightweight, modular covers that could be erected and struck in minutes, supporting the mobility of mechanized infantry in theaters like Europe and the Pacific. These features underscored the enduring military value of bivouacs for rapid setup, minimal logistics, and integration with defensive tactics.[20] Contemporary military training continues this tradition, incorporating bivouacs into survival and field exercises to build resilience. In the U.S. Army's Basic Combat Training as of 2025, bivouacs form part of Field Training Exercises (FTXs) like HAMMER and FORGE, where recruits practice austere living, field sanitation, land navigation, and tactical casualty care in simulated combat environments. These sessions emphasize sex-segregated sleeping areas, roving security patrols, and improvised hygiene methods such as slit trenches, preparing soldiers for operational deployment while reinforcing the historical focus on mobility and self-reliance.[21]Adoption in Mountaineering and Outdoor Recreation

The adoption of bivouac shelters in mountaineering and outdoor recreation marked a significant transition from their military origins, where they served as temporary field encampments, to essential tools for civilian explorers navigating remote and high-altitude environments. In the 19th century, European mountaineers in the Alps increasingly relied on improvised bivouacs to overcome the limitations of fixed campsites and harsh weather, enabling longer expeditions and first ascents of challenging peaks. This shift was driven by the "Golden Age" of alpinism (1854–1865), during which pioneers like Edward Whymper popularized their use for emergency overnight stays on exposed ridges and faces. A key milestone occurred during Whymper's 1865 first ascent of the Matterhorn, where his party established a bivouac at 3,380 meters before summiting, demonstrating the practicality of such shelters in technical climbing scenarios.[22][23] By the early 20th century, bivouac techniques gained traction in broader recreational contexts, particularly through organized youth movements and polar exploration. Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Scout movement, promoted natural bivouac construction in his 1908 manual Scouting for Boys, emphasizing their role in teaching self-reliance and minimal-impact camping to young participants in hiking and outdoor activities. In extreme environments, such as Antarctic expeditions, bivouacs proved vital for survival; during Robert Falcon Scott's 1910–1913 Terra Nova Expedition, members like those wintering on Inexpressible Island resorted to excavated snow caves as improvised shelters when fixed camps were inaccessible due to pack ice. The section also saw use in other explorations, such as Arctic sledging parties where lightweight natural or improvised covers were essential for mobility in subzero conditions.[24] The post-World War II era further accelerated adoption with the advent of lightweight gear derived from military surplus, including nylon bivouac sacks and down-filled components, which reduced pack weights and facilitated extended backpacking trips in North American and European trails.[25] As of 2025, bivouac shelters remain integral to ultralight backpacking philosophies, aligning with Leave No Trace principles that prioritize low-impact practices in fragile ecosystems. Environmental regulations in designated wilderness areas, such as those managed by the U.S. National Park Service, often mandate bivouacs for technical climbers to avoid permanent structures and minimize site disturbance, as seen in Rocky Mountain National Park's policies for multi-pitch routes requiring permits, no tents, and setup only at dusk. This integration reflects a broader emphasis on sustainability, where bivouacs enable dispersed, trace-free camping amid growing restrictions on fixed camps in protected terrains like the Alps and U.S. backcountry.[26][27][28]Types of Bivouac Shelters

Improvised Natural Shelters

Improvised natural shelters represent a fundamental approach to bivouacking in wilderness environments, relying exclusively on readily available organic materials to create protective enclosures against the elements. These structures are particularly valuable in survival scenarios where no equipment is present, allowing individuals to conserve energy while establishing quick refuge. By utilizing local foliage and timber, such shelters integrate seamlessly into the landscape, offering both thermal regulation and concealment from potential threats. Among the core types, the lean-to shelter involves propping a long ridgepole between two upright supports or against a natural feature like a tree trunk or rock, then layering smaller branches at an angle against the ridgepole and covering them with insulating materials such as leaves or bark. This open-sided design provides basic wind protection and is suitable for milder conditions. The debris hut, conversely, forms a low-lying enclosure with a simple frame—often a ridgepole elevated on forked sticks—overlaid with a substantial pile of forest debris like leaves, pine needles, or ferns to create an insulated cavity large enough for one person to curl inside. Its enclosed nature excels in retaining body heat during cold nights. The A-frame variant employs two sturdy poles lashed together at the top to form an inverted V, with additional cross-branches and fallen logs added for support, followed by a debris covering to seal the structure against precipitation.[29] These shelters offer distinct advantages in bushcraft and emergency contexts, as they require no specialized gear and can be assembled rapidly using environmental resources, thereby promoting self-reliance in remote areas. Their use of natural camouflage—blending with surrounding vegetation—enhances security in survival situations, while materials like ferns and pine needles provide effective insulation by trapping air pockets that retain warmth. Unlike portable synthetic options, they emphasize minimal environmental footprint when constructed properly. Key construction principles begin with site selection, prioritizing locations shielded from prevailing winds and direct rain, such as lee sides of hills, natural depressions, or beneath overhanging rock formations to maximize protection and reduce material needs. Frames are built using flexible, fallen branches to form the basic skeleton, avoiding the need for cutting tools while ensuring stability; for instance, live but flexible saplings may be bent if necessary, though modern practices discourage this. Insulation is critical for warmth, with debris layers typically 18 to 24 inches deep around the shelter's walls and roof to create a barrier that prevents convective heat loss, allowing body heat to raise internal temperatures sufficiently for rest.[30] In line with 2025 updates to outdoor ethics, sustainable practices for these shelters stress adherence to Leave No Trace guidelines, which explicitly advise against damaging live trees or vegetation by using only deadwood, downed branches, and shed foliage to prevent habitat disruption and long-term ecological harm. This approach ensures that the site can be dismantled post-use with negligible impact, aligning with broader conservation efforts in forested areas.[31]Bivouac Sacks

A bivouac sack, commonly referred to as a bivy sack or bivy bag, is a lightweight, minimalist shelter consisting of a waterproof and breathable fabric envelope designed to encase a sleeping bag and sleeping pad for protection during overnight stays in the outdoors.[3] Typically constructed with a durable nylon floor coated in polyurethane for waterproofing and an upper layer of breathable membrane such as Gore-Tex or Pertex Quantum to allow moisture vapor escape while blocking liquid water, these sacks feature a hooded opening with a zipper or drawcord for ventilation and entry.[3][32] Weighing between 0.5 and 1 kg for ultralight models, they are compact when packed, often fitting into a space the size of a water bottle, making them ideal for weight-conscious adventurers.[33] The development of modern bivouac sacks traces back to the late 1970s, when mountaineering brands like Marmot began incorporating Gore-Tex fabric into bivy designs for alpine expeditions, providing enhanced weather resistance over earlier improvised coverings used in big-wall and high-altitude climbing.[34] This innovation aligned with the rise of lightweight alpinism, where climbers needed portable protection for unplanned overnights on routes like those in the Alps and Himalayas, evolving from military surplus tarps and basic waterproof bags into specialized gear produced by companies such as The North Face and Outdoor Research.[8] In practice, bivouac sacks serve primarily to shield users from rain, wind, and ground moisture while minimizing internal condensation through breathable materials, but they are not intended as standalone shelters and must be paired with a sleeping bag for warmth and insulation.[3] Available in standard solo sizes accommodating one person and their gear, or larger tandem models for two users, they excel in scenarios requiring rapid setup, such as ultralight backpacking or technical ascents, where space and weight constraints preclude full tents.[35] Unlike improvised natural shelters, which rely on environmental materials, bivy sacks offer manufactured portability for consistent weatherproofing.[3] Contemporary bivouac sacks as of 2025 incorporate sustainable advancements, including recycled polyester fabrics that maintain high waterproof ratings (often 10,000mm+) without perfluorocarbons (PFCs), as seen in models from Rab and Mountain Equipment, reducing environmental impact while preserving durability.[36] Many designs now integrate no-see-um mesh panels or full bug netting hoods for insect protection, and modular attachments like compatible stuff sacks or stake-out points allow customization for varied terrains, enhancing versatility in bug-prone or multi-day alpine environments.[33][37]Specialized Variants

Specialized variants of bivouac shelters adapt standard designs for extreme or niche activities, emphasizing minimal weight, rapid deployment, and environmental integration in challenging terrains. Bivouac tents, often ultra-light single-wall structures, provide enhanced ventilation and protection compared to basic sacks while maintaining portability for long-distance pursuits. These tents typically weigh between 0.5 and 1.5 kg, using materials like Dyneema or silnylon for durability and low pack volume, making them suitable for thru-hiking or fastpacking where every gram counts.[38][39][40] Portaledges represent a critical adaptation for big-wall climbing, consisting of suspended aluminum-framed platforms with fabric beds and optional rain flies to shield against exposure. These deployable systems hang from anchors on sheer rock faces, allowing climbers to rest securely mid-route without descending, and are commonly equipped with sidewalls for wind and precipitation resistance. In Yosemite National Park, portaledges have been integral to historic ascents of El Capitan, where multi-day wall climbs demand overnight accommodations hundreds of feet above the ground.[41][42][43] Boofen, a regional practice in German climbing culture, refers to minimalist bivouacs under natural rock overhangs, particularly in the Elbe Sandstone Mountains of Saxon Switzerland. Originating among traditional climbers seeking low-impact overnight stays, boofen involves using sleeping bags, tarps, or sacks on exposed ledges without tents to prioritize speed and environmental harmony on multi-pitch routes. Designated sites—limited to 58 locations outside core protected areas—enforce strict rules like no fires or trace removal to preserve the fragile sandstone ecosystem.[44][45][46] Hammock-based bivouacs incorporate underquilts to address cold-ground insulation challenges, suspending a quilt beneath the hammock to trap body heat and prevent convective loss in forested or uneven terrains. These setups, often paired with lightweight tarps for overhead cover, enable elevated sleeping that avoids wet or rocky surfaces, with underquilts rated for temperatures down to 0°F using synthetic or down fills. This variant suits woodland adventures where flat ground is scarce, enhancing comfort without adding significant bulk.[47][48] In polar or high-latitude conditions, snow caves integrate with bivouac sacks for thermal regulation, where excavated snow domes trap body heat to maintain internal temperatures near 32°F even in subzero exteriors. These improvised vaults, reinforced by their own structure against wind, provide a hybrid shelter for expeditions in Arctic or Antarctic environments, often lined with minimal gear for moisture control. Recent innovations, such as the solar-powered bivouac by Carlo Ratti Associati unveiled in 2025, incorporate photovoltaic panels and digital fabrication for heated, off-grid alpine units deployable via helicopter, designed to withstand extreme weather while debuting at the 2026 Winter Olympics.[49][50][51]Construction Techniques

Materials and Tools

Bivouac shelters often rely on readily available natural materials for structure and insulation, such as branches for framing, leaves or pine boughs for layering to trap heat, snow for packing into walls or caves in cold environments, and rocks to form windbreaks or low walls.[52] When sourcing wood, non-resinous hardwoods like oak or birch are preferred over softwoods such as pine or fir to minimize fire hazards from excess sap and smoke if a nearby campfire is used.[53] Sustainability practices emphasize using only deadfall—fallen branches and leaves—to avoid damaging live vegetation and promote environmental leave-no-trace principles.[54] Synthetic materials provide lightweight, portable alternatives, particularly for bivouac sacks and tarp-based shelters, including nylon or silnylon tarps typically sized 1-3 m² for quick setup as roofs or walls, ponchos that double as groundsheets, guy lines for tensioning, and stakes for securing.[3] Bivouac sacks themselves feature a durable urethane-coated nylon bottom for waterproofing and a ripstop nylon top with breathable laminates like Gore-Tex for moisture management, often incorporating straps to secure sleeping pads.[3] Additional options include multi-use emergency blankets made from reflective Mylar for thermal insulation in improvised setups.[55] Tools for bivouac construction remain minimalist to support portability, primarily a knife for cutting branches or cordage, natural or synthetic cordage (such as paracord) for binding elements, and multi-functional items like a trekking pole serving as a ridgepole without requiring heavy equipment.[52] Material and tool selection depends on prevailing weather: waterproof synthetics like coated nylon tarps or bivouac sacks are essential for rain to prevent moisture ingress, while insulating natural options such as pine boughs or snow provide thermal protection in cold conditions when layered properly.[3] For instance, improvised natural shelters may prioritize abundant local deadfall in forested areas, whereas high-altitude mountaineering variants favor compact synthetic bivouac sacks for their breathability in variable alpine weather.[3]Building Methods

Building a bivouac shelter involves a systematic process starting with site assessment to ensure safety and effectiveness. Select a location on level, well-drained ground that shields against prevailing winds, such as behind natural barriers like rocks or dense vegetation, while avoiding low-lying areas prone to flooding or flash runoff. Inspect overhead for widowmakers—dead or loose branches that could fall—and steer clear of them to prevent injury. Foundation setup requires clearing debris, rocks, and moisture from the sleeping area, then layering insulating materials like dry leaves, pine needles, or a ground cloth to elevate off cold soil. The covering phase constructs the overhead protection, followed by securing all elements against movement. Basic bivouac shelters can be erected in 5 to 30 minutes with practice and available materials, allowing quick protection in emergencies.[56][57][58] Specific methods vary by available resources but emphasize simplicity and stability. For an improvised lean-to using natural materials, tie a sturdy ridgepole horizontally at chest height between two trees or upright supports, then lean additional branches at a 45-degree angle against it to form the back wall and roof. Layer the structure with overlapping foliage, moss, or bark for waterproofing and insulation, ensuring the open side faces away from wind. For a tarp-based A-frame, establish a taut ridgeline between two anchor points like trees or trekking poles, drape the tarp evenly over it, and stake the corners outward with tension lines to create a peaked roof that sheds water; adjust guy lines for tautness to prevent sagging. Bivouac sack deployment is straightforward: unzip the long end opening to crawl inside with sleeping gear, then reseal it tightly while positioning the sack on a moisture-barrier ground sheet to block ground dampness and condensation. These techniques draw from common materials like cordage and tarps detailed in preparatory sections.[56][58][59] Safety considerations are paramount during construction to mitigate risks like structural failure or environmental exposure. Always verify the shelter's stability by testing supports before occupancy, and incorporate ventilation—such as leaving a small gap at the entry or using breathable fabrics—to avoid trapped moisture that accelerates hypothermia by chilling the body through evaporation. In 2025, modern tools like GPS-enabled apps such as Gaia GPS facilitate precise site selection by overlaying topographic data to pinpoint elevated, hazard-free spots with optimal wind protection and drainage. Common errors include overpacking or disturbing the site excessively, which harms local ecosystems and leaves traces, or skimping on anchoring, allowing wind to dislodge the structure and expose occupants to the elements.[57][60][61][62][63]Uses and Examples

Applications in Survival and Military Contexts

In survival situations, bivouac shelters serve as critical emergency protections against environmental hazards, particularly for lost hikers or stranded individuals in wilderness settings. Among the core survival priorities—often outlined as shelter, fire, water, and food—shelter ranks first to prevent hypothermia, hyperthermia, or exposure-related injuries by shielding the body from wind, rain, precipitation, and extreme temperatures.[64][65] Improvised natural bivouacs, such as debris huts constructed from leaves, branches, and snow, enable rapid assembly using available forest materials, providing insulation and concealment for overnight stays during unexpected delays or injuries.[66] These structures prioritize low-energy construction to conserve the survivor's strength, emphasizing site selection that avoids hazards like falling branches or flooding.[67] To enhance warmth within a bivouac shelter, integration with fire-building techniques is essential, typically involving an external fire pit positioned a few feet away to direct radiant heat inward via a reflector wall of rocks or logs. This method avoids the risks of internal fires, such as smoke inhalation or structural ignition in flammable natural materials, while still boosting internal temperatures effectively in cold conditions.[68] Heated stones from the fire can also be safely transferred inside for sustained warmth, aligning with the second survival priority of fire for morale, signaling, and thermal regulation alongside shelter.[65] In military contexts, bivouac shelters remain integral to contemporary training and operations, enabling forces to maintain operational readiness during field exercises and deployments. U.S. Marine Corps units, for instance, routinely establish bivouac sites as part of wing support squadron drills, such as those conducted at Fort Stewart in 2022, where Marines quickly site and erect temporary camps to simulate sustained field presence.[69] NATO allies incorporate similar bivouac practices in multinational exercises, focusing on rapid deployment and environmental adaptation to bolster collective defense capabilities, as seen in the 2025 Steadfast Dart exercise.[70] These applications emphasize bivouacs' role in marshaling troops at combat-functional status without permanent infrastructure, drawing from established mountain and cold-weather doctrines. Tactically, bivouac shelters offer advantages in asymmetric warfare through their low-profile design, which facilitates quick hides in diverse terrains like urban fringes or jungles, minimizing detection by superior forces. Camouflage integration, using patterned materials or natural cover, enhances concealment for small units, while multi-person configurations—such as two-person poncho tents—support team cohesion without compromising mobility.[71] U.S. Marine Corps fieldcraft training stresses efficient bivouac drills for setups under 15 minutes, prioritizing security, sustainability, and low observability in contested environments.[72] In mountain or cold operations, these shelters provide indigenous forces with terrain-exploiting edges, allowing defensive positioning that preserves warmth and protection over offensive maneuvers.[73] Post-2020 developments have introduced climate-adaptive enhancements to bivouac shelters for extreme weather events, driven by intensified storms and temperature shifts in military and survival scenarios. Rapidly deployable systems, like insulated fabric enclosures, now feature modular add-ons for flood-prone or high-wind areas, enabling quick reconfiguration for resilience in humanitarian or combat aid roles.[74] For harsh cold, heat, or storms, updated designs incorporate reflective linings and ventilation to mitigate condensation and heat loss, tailored to evolving climate threats. These adaptations ensure bivouacs remain viable in prolonged exposure, aligning with broader military emphases on environmental sustainability in training.Notable Mountaineering Examples

One of the most iconic uses of bivouac shelters in mountaineering history occurred during the 1938 first ascent of the Eiger's North Face by German-Austrian climbers Anderl Heckmair, Ludwig Vörg, Heinrich Harrer, and Fritz Kasparek. Over four days from July 21 to 24, the team endured multiple unplanned and planned bivouacs on the 1,800-meter ice- and rock-covered wall, huddling in sleeping bags lashed to ledges amid falling stones and subzero temperatures to conserve strength for the technical pitches above.[75] This grueling exposure highlighted the necessity of lightweight, improvised setups like rope slings and minimal tarps for multi-day alpine pushes, influencing subsequent "Boofen" (big wall) techniques on similar European faces through the 1980s, where climbers like Jerzy Kukuczka and Wojciech Kurtyka adapted similar endurance bivouacs during rapid ascents. In the 1924 British Everest expedition, George Mallory and Andrew Irvine established what was then the world's highest camp at approximately 8,170 meters on the Northeast Ridge, functioning as a rudimentary bivouac with oxygen gear and sleeping bags but no full tent due to the extreme altitude and wind. Departing from this high camp on June 8 for their summit attempt, the pair's fate remains unknown, but the setup underscored the risks of unprotected overnight exposure above 8,000 meters, where hypothermia and oxygen deprivation claimed many early Himalayan pioneers.[76] The 1953 British Everest expedition, led by John Hunt, relied on a series of high-altitude bivouacs, including a high camp at approximately 8,500 meters (27,900 feet) described as a precarious ledge shelter with a single tent, to stage the successful summit push by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. These improvised platforms, reinforced with snow walls against gale-force winds, allowed acclimatization and gear caching, though the climbers faced severe cold that limited sleep and recovery.[77] Modern examples include big-wall ascents on Yosemite's El Capitan, where portaledge bivouacs—suspended aluminum-framed platforms with rainflies—enable multi-day free climbs. During Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson's 19-day first free ascent of the Dawn Wall in January 2015, the duo spent nights in double portaledges hung from bolts, battling subfreezing temperatures and skin injuries while progressing bolt-to-bolt without aid. Similarly, in preparation for his 2017 free solo of Freerider on El Capitan, Alex Honnold practiced the route multiple times using minimal bivouac gear, including lightweight sacks and portaledges for overnight stays to memorize sequences, though the final ascent was completed in under four hours without stopping.[78] Recent 2024-2025 seasons have seen free-solo and speed climbers on El Capitan incorporating ultralight portaledge variants for hybrid pushes, such as during the Nose route speed records, emphasizing ventilation and quick-deploy designs to mitigate condensation buildup. Bivouacs played a critical role in survival during the 1996 Mount Everest disaster, when a sudden blizzard on May 10-11 trapped multiple teams above 8,000 meters. Climbers like Taiwanese expedition leader Makalu Gau endured an unplanned open-air bivouac at 8,200 meters, wrapping in minimal insulation and sharing body heat to survive 14 hours of -30°C winds before rescue; similarly, guide Rob Hall bivouacked with client Doug Hansen near the South Summit but perished from exposure.[79] These events spurred innovations in bivouac sack design, such as Gore-Tex laminates with improved ventilation zippers to prevent fatal moisture accumulation, as analyzed in post-disaster reports.[80] Lessons from such failures, including the need for emergency bivy kits in summit packs, have reduced fatalities in high-altitude storms by enhancing thermal retention without added weight.[81]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Biwak