Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Boston Post Road

View on Wikipedia

Boston Post Road | |

|---|---|

Routes of the Boston Post Road | |

| Major junctions | |

| South end | |

| North end | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| Highway system | |

The Boston Post Road was a system of mail-delivery routes between New York City and Boston, Massachusetts, that evolved into one of the first major highways in the United States.

The three major alignments were the Lower Post Road (now U.S. Route 1 (US 1) along the shore via Providence, Rhode Island), the Upper Post Road (now US 5 and US 20 from New Haven, Connecticut, by way of Springfield, Massachusetts), and the Middle Post Road (which diverged from the Upper Road in Hartford, Connecticut, and ran northeastward to Boston via Pomfret, Connecticut).

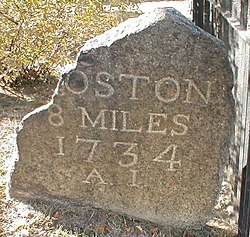

In some towns, the area near the Boston Post Road has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places, since it was often the first road in the area, and some buildings of historical significance were built along it. The Boston Post Road Historic District, including part of the road in Rye, New York, has been designated a National Historic Landmark. The Post Road is also famous for milestones that date from the 18th century, many of which survive to this day. In parts of Connecticut (generally east of Hartford), it is also known as Route 6.

History

[edit]The Upper Post Road was originally called the Pequot Path and had been in use by Native Americans long before Europeans arrived.[1] Some of these important native trails were in many places as narrow as two feet.[2]

What is now called the Old Connecticut Path and the Bay Path were used by John Winthrop the Younger to travel from Boston to Springfield in November 1645, and these form much of the basis for the Upper Post Road.

The colonists first used this trail to deliver the mail using post riders. The first ride to lay out the Upper Post Road started on January 1, 1673.[3] Later, the newly blazed trail was widened and smoothed to the point where horse-drawn wagons or stagecoaches could use the road. The country's first successful long-distance stagecoach service was launched by Levi Pease along the upper road in October 1783.[4]

During the 19th century, turnpike companies took over and improved pieces of the road. Large sections of the various routes are still called the King's Highway and Boston Post Road. Much of the Post Road is now U.S. Route 1, U.S. Route 5, and U.S. Route 20.

Mileposts were measured from the intersection of Broadway and Wall Street in New York (one block west of Federal Hall) and from the old Boston city-line on Washington Street, near the present-day Massachusetts Turnpike.

The Metropolitan Railroad Company was chartered in 1853 to run streetcars down the stretch of the road on Washington Street in Roxbury, which is now served by the MBTA Silver Line. The Upper and Lower Boston Post Roads were designated U.S. Routes 1 and 20 in 1925 (though Route 20 has since been substantially modified).[4]

New York

[edit]

Manhattan

[edit]Much of the route in Manhattan, where it was known as the Eastern Post Road, was abandoned between 1839 and 1844, when the current street grid was laid out as part of the Commissioners' Plan that had been originally advanced in 1811.[5] The following sections of the road still exist:

- Broadway – Park Row – Bowery – Fourth Avenue – Broadway from Wall Street (the southern end of the Post Road) to Madison Square Park

- There is a large gap in midtown Manhattan before Post Road resumes its course north of Central Park

- St. Nicholas Avenue-Broadway: St. Nicholas Avenue from 110th Street (with a realignment near 145th Street), switching to Broadway at 169th Street and continuing to 228th Street

- 228th Street-Kingsbridge Avenue from Broadway to the old Kings Bridge over the old Harlem River bed. (The course of the Harlem River was altered in 1895.)

These milestones were once present in Manhattan:

- 1 – the west side of Bowery near Rivington Street[6]

- 2 – southwest corner of Astor Place and Fourth Avenue

- 3 – Madison Avenue and 26th Street

- 4 – east side of Third Avenue, halfway between 45th Street and 46th Street

- 5 – west side of Second Avenue at 62nd Street

- 6 – northwest corner of Third Avenue and 81st Street

- 7 – in Central Park, west of Fifth Avenue, between 97th Street and 98th Street

- 8 – St. Nicholas Avenue, west side, between 115th Street and 116th Street

- 9 – St. Nicholas Avenue, west side, opposite north line of 133rd Street

- 10 – southwest corner of St. Nicholas Avenue and 152nd Street

- 11 – Broadway, west side, near 170th Street or 171st Street ~ Now at Roger Morris Park next to the Morris-Jumel Manse 40°50'04.7"N 73°56'18.5"W

- 12 – Broadway, west side, at or near 189th Street ~ Now at the Broadway entrance to Isham Park 40°52'06.4"N+73°55'08.9"W

- 13 – east side of Broadway between Academy Street and 204th Street

- 14 – Broadway, west side, between 225th Street and 228th Street

The Bronx

[edit]

In southwestern Westchester County, now the Bronx, the Boston Post Road came off the Kings Bridge and quickly turned east, with the Albany Post Road continuing north to Albany, New York. It passed over the Bronx River on the Williams Bridge, and left The Bronx on Bussing Avenue, becoming Kingsbridge Road in Westchester County. In more detail, it used the following modern roads:

- Kingsbridge Avenue – 230th Street – Broadway – 231st Street

- Albany Post Road continued north on Albany Crescent

- Albany Crescent – Kingsbridge Terrace – Heath Avenue

- gap across Jerome Park Reservoir

- Van Cortlandt Avenue

- gap at Williamsbridge Reservoir

- Reservoir Place – Gun Hill Road – White Plains Road (southbound lanes)

- gap from near 217th Street to near 231st Street

- Bussing Avenue

- gap from Grace Avenue to De Reimer Avenue

- Bussing Place – Bussing Avenue

Westchester County

[edit]The Boston Post Road entered what is now Westchester County on Kingsbridge Road, and turned north on Third Avenue-Columbus Avenue (Route 22), forking off onto Colonial Place. It continued across Sandford Boulevard (Sixth Street) where there is no longer a road, and curved east and southeast around the hill, hitting Sandford Boulevard-Colonial Avenue at the Hutchinson River Parkway interchange. It then continued east on Colonial Avenue-Kings Highway, merging with U.S. Route 1. From there to the Connecticut border, the Post Road used US 1, except for several places, where Post Road used the following roads:

- The southbound side of US 1-Huguenot Street through downtown New Rochelle.

- Old Boston Post Road north of downtown New Rochelle.

- Old Post Road-Orienta Avenue south of downtown Mamaroneck.

- Mamaroneck Avenue-Prospect Avenue-Tompkins Avenue north of downtown Mamaroneck.

- Old Post Road at Playland Parkway in Rye.

Upper Post Road

[edit]The Upper Post Road was the most traveled of the three routes, being the furthest from the shore and thus having the fewest and shortest river crossings. It was also considered to have the best taverns, which contributed to its popularity.[citation needed] The Upper Post Road roughly corresponds to the alignment of U.S. Route 5 from New Haven, Connecticut, to Hartford; Connecticut Route 159 from Hartford to Springfield, Massachusetts; U.S. Route 20 from Springfield to Warren, Massachusetts (via Route 67); Massachusetts Route 9 from Warren to Worcester; an unnumbered road (Lincoln Street in Worcester, Main Street in Shrewsbury, and West Main Street in Northborough) to Northborough; and U.S. Route 20 from Northborough to Boston. A series of historic milestones erected in the 18th century survive along its route from Springfield to Boston.

Connecticut

[edit]

Massachusetts

[edit]Lower Post Road

[edit]The Lower Post Road hugged the shoreline of Long Island Sound all the way to Rhode Island and then turned north through Providence to Boston. It traversed what is now the most densely populated part of Connecticut, including the state’s three largest cities; as a result, it is the best-known of the routes today. The Lower Post Road roughly corresponds to the original alignment of U.S. Route 1 in eastern Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.

Connecticut

[edit]

|

|

Rhode Island

[edit]Massachusetts

[edit]In Massachusetts, the Norfolk and Bristol Turnpike was established in 1803 as a straighter route between Pawtucket, Rhode Island, and Roxbury, Massachusetts, mostly west of the Post Road. It is known as Washington Street in many of the towns it passes through. [2] Due to its avoidance of built-up areas, the southern half of this road was little-used. In addition, another well-used route passed west of this turnpike along current Route 1A.

The Post Road entered Massachusetts at the town of Attleboro's Newport Avenue (Route 1A) through the settlement of South Attleboro. It continued northeast on Newport Avenue along Route 123, splitting to the north (staying with Newport Avenue) to cross into North Attleborough.

South of North Attleborough center, the old road is known as Old Post Road. The old road crossed the turnpike (now US 1) just south of the intersection with Route 120, forming a small curve before merging with the turnpike north of the intersection. This curved alignment is now gone, so traffic must use US 1. Additionally, US 1 leaves the turnpike at the Route 120 intersection to bypass North Attleborough center on East Washington Street.

The Lower Post Road passed through North Attleborough Center on Washington Street, later used as part of the turnpike. Another short curved alignment still exists to the west of Washington Street north of the center, now called "Park Street". Just north of this, the route crosses the Ten Mile River and then enters a complicated five-way intersection with US 1 and Route 1A. US 1 straight ahead is the old turnpike, and US 1 to the right was built in the 1930s. The Post Road went to the right onto Elmwood Street. The fork to the left onto Route 1A through Plainville center was an alternate route to Boston.

Elmwood Street enters the town of Plainville, where it becomes Messenger Street. The road merges with Route 106 before crossing Route 152 at Wilkins Four Corners and entering Foxborough.

There is a road passing from the town of Sharon into East Walpole which is known as Old Post Road, which continues north as Pleasant Street into Norwood. [3]

- East Walpole (part of Walpole)

In Norwood, the oldest route of the Post Road followed Neponset Street south until the intersection with Pleasant Street. The newer route followed Washington Street through the center of Norwood, south towards Walpole.

The Post Road turned from East Street onto Washington Street, heading south towards Norwood.

In Dedham, the road followed modern-day Lower East Street north to Boston. Here the Post Road splits, with the oldest route (prior to 1704) following East Street in an arc around the old marshes until it meets Washington Street (Route 1A) south of the Dedham village center.

The new road (in use by 1744) followed High Street to Court Street, and continued south along Highland Street and Elm Street, rejoining East Street south of Interstate 95.

In Roxbury, the road turned down Roxbury Street and followed modern-day Centre Street around the edge of Fort Hill, crossing Stony Brook at a bridge in the location of the modern-day Jackson Square MBTA station. The road continued following Centre Street southwards through modern-day Hyde Square and Jamaica Plain, and southwards to Dedham.

In the colonial city, the road began at the Old State House, the government center of the 18th-century city. Once called Cornhill, Orange, and Newbury Street, it's now modern-day Washington Street, running southwards off the Boston Neck towards the village of Roxbury.

Middle Post Road

[edit]The Middle Post Road was the shortest, fastest, and youngest portion of the route. From Hartford, it ran into the Eastern Upper Highlands, an area with large native Indian populations. During King Philip's War of 1675, travel in these areas was often dangerous for settlers. It was not until the end of the war and establishment of the Colonial post system that the area began to become populated, and the middle post road was established as the fastest route. This area of the state continues to remain underpopulated in contrast to other portions of Connecticut, and accordingly, portions of the original post road have been preserved due to various circumstances. It split from the Upper Post Road in Hartford, and initially ran roughly along current U.S. Route 44 through Bolton Notch and towards Mansfield Four Corners. From Mansfield, it went through Ashford, Pomfret, and headed into Massachusetts via the town of Thompson, along Thompson Road. In Massachusetts, the Middle Post Road runs along sections of modern Route 16 to Mendon, then through Bellingham, and then via Route 109 from Medway to Dedham where it meets with the Lower Post Road (old U.S. Route 1) heading into Boston.

Connecticut

[edit]Starting at the Old State House, the road crossed the Connecticut River over the area that is now occupied by the Founders Bridge, initially by ferry and later by bridge. It is notable that until 1783, Hartford's eastern boundaries included present-day East Hartford and Manchester.

Although the road crossed via the route of the Founders Bridge from Hartford, this area was later developed into an enormous highway interchange, and thus much of the historic road was destroyed. In the early years of Connecticut's history, East Hartford was privately owned. What remains of the route is the path of Interstate 84 / Route 6, which connects to Manchester's Middle Turnpike East.

Since Manchester was a part of Hartford until 1783, the area was made up of settlements and present-day boroughs. The post road can be traced along present-day Middle Turnpike East through central Manchester. It later passed through Manchester Green, where the post road became reconnected with Route 6, and, for the first time, U.S. Route 44. Just before leaving Manchester and entering Bolton, the post road breaks off Route 44 onto Middle Turnpike East (the portion of Route 44 between Manchester and Bolton is known as "New Bolton Road")

Bolton serves a unique role in the post road, as it was the border between the flat and tranquil Connecticut River Valley, and the hilly and turbulent Eastern Upper Highlands. Entering Bolton on Middle Turnpike East, the traveler encountered a fork and could choose to head southeast on Bolton Center Street (later Center Street) to the settlement of Bolton, or stay on Middle Turnpike East to reconnect with Route 44 and head east on the original Mohegan Indian Trail through Bolton Notch, a natural depression in the ridge that dramatically sped up transit and served as a demarcation between the two geologic landscapes. Within the Bolton settlement was White's Tavern, notable for having housed the staff of General Rochambeau, whose unit camped in the settlement during the revolutionary war. To exit Bolton, one heads north on Notch Road until reaching Route 44, just outside Bolton Notch. Route 44 then connects to Coventry.

Between Bolton and Mansfield, the road passed through the borough of North Coventry, entirely along present-day U.S. Route 44, known locally as the Boston Turnpike. Along the Willimantic River (and border of Mansfield) stands the Brigham Tavern, which holds the distinction of having housed George Washington around the period of the Revolutionary War. This plaque can be seen in front of the Brigham Tavern; it is currently a private residence.

Like Coventry, the post road follows the path of present-day U.S. Route 44. After crossing the Willimantic River from Coventry, the road crosses through Mansfield Four Corners, and towards Ashford.

The road connects on Route 44 from Mansfield, and runs directly through the borough of Ashford. It stops, however, at Phoenixville, which then heads north towards Eastford on Route 198. Before reaching Eastford, however, it takes a right onto Route 244 ("Brayman Hollow Road") which headed directly to Pomfret.

At the center of Pomfret, Route 244 headed east turns into U.S. Route 44. The post road turns left shortly after the intersection with Route 169 onto Allen Road which quickly merges into Freedley Road. The road then heads northeast into Woodstock.

The post road briefly passes through the Harrisville section of town on Tripp Road before entering Putnam.

Soon after entering Putnam, the road crosses over Route 171 onto West Thompson Road headed into Thompson.

The post road soon follows over West Thompson Dam. The road once passed through the village of West Thompson, which was flooded purposely to control the Quinebaug River. The original post road can be seen from the Dam when water levels in West Thompson Lake are low enough. Once over the Dam the road turns into Route 193 and travels through historic Thompson Hill. Continuing northeast, the road bears right at a fork onto East Thompson Road and follows all the way to the Massachusetts state line.

Massachusetts

[edit]Crosses the Massachusetts state line into the town of Douglas as Southwest Main Street. This section passes through Douglas State Forest and is one of the most remote parts of the route that is still used as a public road. A 1-mile (1.6 km) section here was still unpaved until 2002. At the center of Douglas, the Post Road follows Massachusetts Route 16 eastward to East Douglas. Where Route 16 turns south, the Post Road continues east as Northeast Main Street, which leads to the Uxbridge town line. French General Lafayette traveled this road to join forces with Washington, and stopped in Douglas during the Revolutionary War.

Entering Uxbridge, the name of the road changes to Hartford Avenue. Hartford Avenue is a major cross-town road and follows the route of the Post Road for its entire length. From the Douglas town line to the intersection of Massachusetts Route 122, it is known as Hartford Avenue West; from Route 122 to the Mendon town line, it is known as Hartford Avenue East. The original stone arch bridge over the Blackstone Canal is still in use today. There was a Civil War encampment near the stone-arch bridge, and the road was used by troops during the French and Indian Wars and as a supply route during the War of 1812. George Washington stopped here a number of times when traveling this road, including when he took command of the Continental Army at Boston in 1775, and on his post-Inaugural tour of New England in 1789.

The Post Road enters the town from Uxbridge as Hartford Avenue West. It follows that road to Route 16, which follows the route of the Post Road for approximately one-half-mile eastward to Maple Street, which follows the route into Mendon town center. From there, the Post Road followed a Providence-Worcester post road south out of the village. This section is now part of Providence Street. About 1-mile (1.6 km) south of the town center the roads diverged. The Post Road heads east, now known as Hartford Avenue East. This road follows the original Post Road route to the Bellingham town line. Historic milestone 37 is still located along the route.[4]

The Post Road enters from Mendon as Hartford Avenue. Massachusetts Route 126 joins the road shortly before crossing over Interstate 495. Route 126 follows the Post Road route the remainder of the way to the Medway town line.

The original Post Road from Mendon followed Village Street through Medway to the Tavern and Inn in Medway Village near the Charles River. The post road followed (present day) Village Street through Millis (part of Medway until 1885). In the early 19th century, the Hartford and Dedham Turnpike was built (now Rt 109), a straight route built through the Great Black Swamp, and up a large hill in the center of town.

The original Post Road in Millis followed Village St from Medway, crossing current Massachusetts Rt 109, and then following the current Dover Road to the location of a series of Bridges over the Charles River leading into Medfield. In the period from 1806 to 1810, the Hartford and Dedham Turnpike was built (now Route 109), nearly going broke in attempting to build a causeway over the Charles River at the Medfield town line and through the Great Black Swamp.

The upper post road (US 20) also runs through Weston, and links directly to The Gifford School

In popular culture

[edit]- The Long Walk – a novel by Stephen King published under the pseudonym Richard Bachman in 1979 as a paperback original – revolves around the contestants of a gruelling walking contest along a route that roughly follows and extends beyond the Boston Post Road.

- In the 1957 I Love Lucy episode "Lucy Raises Tulips", Lucy loses control of a riding lawn mower while mowing the lawn at the Ricardos' Westport home, and later describes riding it down the Boston Post Road "for a mile and a half, against traffic all the way".

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Bourne, p.13

- ^ Clark, George Larkin (1914). A History of Connecticut. ISBN 9780722249826.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Daughters of the American Revolution Magazine, January 1917, Vol. 50, page 386, [1]

- ^ a b "How the Post Road wrote New England’s history", The Boston Globe

- ^ Walsh, Kevin (July 2001). "DE-CLASSIFIED 4-A". Forgotten New York. Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- ^ One Mile House, on the corner of Rivington Street, demolished in 1921, was a meeting-ground for Tammany Hall politicians. "Bowery Landmark in $170,000 lease", The New York Times 1 April 1921; the painted sign for One Mile House, on the flank of a building on the east side of Bowery, survived into the 1980s.

Bibliography

- Bourne, Russell, The Red King's Rebellion, 1990, ISBN 0-689-12000-1

- From Path to Highway: The Story of the Boston Post Road by Gail Gibbons, ISBN 0-690-04514-X, HarperCollins, 1986

- Horseback on the Boston Post Road, by Laurie Lawlor, ISBN 0-7434-3626-1, Aladdin, 2002

- 1789 strip map from New York to Stratford (0–73)

Further reading

[edit]- Jaffe, Eric, The King's Best Highway: The Lost History of the Boston Post Road, the Route That Made America, New York: Scribner, June 2010. ISBN 978-1-4165-8614-2.

External links

[edit]- West Brookfield milestones (upper 67–69)

- Post Roads and Milestones [New York] City History Club, 1915

- New York Press – Post Road

- Hartford & Dedham Turnpike