Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Light therapy

View on Wikipedia| Light therapy | |

|---|---|

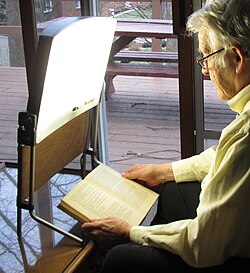

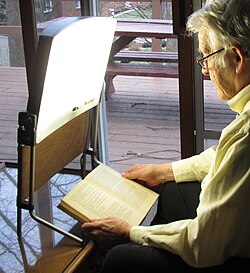

Example of light therapy for winter depression | |

| ICD-10-PCS | 6A6, GZJ |

| ICD-9 | 99.83, 99.88 |

| MeSH | D010789 |

Light therapy, also called phototherapy or bright light therapy, is the exposure to direct sunlight or artificial light at controlled wavelengths in order to treat a variety of medical disorders, including seasonal affective disorder (SAD), circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders, cancers, neonatal jaundice, and skin wound infections. Treating skin conditions such as neurodermatitis, psoriasis, acne vulgaris, and eczema with ultraviolet light is called ultraviolet light therapy.

Medical uses

[edit]

Nutrient deficiency

[edit]Vitamin D deficiency

[edit]Exposure to UV-B light at wavelengths of 290-300 nanometers enables the body to produce vitamin D3 to treat vitamin D3 deficiency.[1]

Skin conditions

[edit]

Light therapy treatments for the skin usually involve exposure to ultraviolet light.[2] The exposures can be to a small area of the skin or over the whole body surface, as in a tanning bed. The most common treatment is with narrowband UVB, which has a wavelength of approximately 311–313 nanometers. Full body phototherapy can be delivered at a doctor's office or at home using a large high-power UVB booth.[3] Tanning beds, however, generate mostly UVA light, and only 4% to 10% of tanning-bed light is in the UVB spectrum.

Acne vulgaris

[edit]As of 2012[update], evidence for light therapy and lasers in the treatment of acne vulgaris was not sufficient to recommend them.[4] There is moderate evidence for the efficacy of blue and blue-red light therapies in treating mild acne, but most studies are of low quality.[5][6] While light therapy appears to provide short-term benefit, there is a lack of long-term outcome data in those with severe acne.[7]

Atopic dermatitis

[edit]Light therapy is considered one of the best monotherapy treatments for atopic dermatitis (AD) when applied to patients who have not responded to traditional topical treatments. The therapy offers a wide range of options: UVA1 for acute AD, NB-UVB for chronic AD, and balneophototherapy have proven their efficacy. Patients tolerate the therapy safely but, as in any therapy, there are potential adverse effects and care must be taken in its application, particularly to children.[8] According to a study involving 21 adults with severe atopic dermatitis, narrowband UVB phototherapy administered three times per week for 12 weeks reduced atopic dermatitis severity scores by 68%. In this open study, 15 patients still experienced long-term benefits six months later.[9]

Cancer

[edit]According to the American Cancer Society, there is some evidence that ultraviolet light therapy may be effective in helping treat certain kinds of skin cancer, and ultraviolet blood irradiation therapy is established for this application. However, alternative uses of light for cancer treatment – light box therapy and colored light therapy – are not supported by evidence.[10] Photodynamic therapy (often with red light) is used to treat certain superficial non-melanoma skin cancers.[11]

Psoriasis

[edit]For psoriasis, UVB phototherapy has been shown to be effective.[12] A feature of psoriasis is localized inflammation mediated by the immune system.[13] Ultraviolet radiation is known to suppress the immune system and reduce inflammatory responses. Light therapy for skin conditions like psoriasis usually use 313 nanometer UVB though it may use UVA (315–400 nm wavelength) or a broader spectrum UVB (280–315 nm wavelength). UVA combined with psoralen, a drug taken orally, is known as PUVA treatment. In UVB phototherapy the exposure time is very short, seconds to minutes depending on intensity of lamps and the person's skin pigment and sensitivity.

Vitiligo

[edit]About 1% of the human population has vitiligo which causes painless distinct light-colored patches of the skin on the face, hands, and legs. Phototherapy is an effective treatment because it forces skin cells to manufacture melanin to protect the body from UV damage. Prescribed treatment is generally 3 times a week in a clinic or daily at home. About 1 month usually results in re-pigmentation in the face and neck, and 2–4 months in the hands and legs. Narrowband UVB is more suitable to the face and neck and PUVA is more effective at the hands and legs.[14]

Other skin conditions

[edit]Some types of phototherapy may be effective in the treatment of polymorphous light eruption, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma[15] and lichen planus. Narrowband UVB between 311 and 313 nanometers is the most common treatment.[16]

Retinal conditions

[edit]There is preliminary evidence that light therapy is an effective treatment for diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular oedema.[17][18]

Mood and sleep related

[edit]Seasonal affective disorder

[edit]The effectiveness of light therapy for treating seasonal affective disorder (SAD) may be linked to reduced sunlight exposure in the winter months. Light resets the body's internal clock.[19] Studies show that light therapy helps reduce the debilitating depressive symptoms of SAD, such as excessive sleepiness and fatigue, with results lasting for at least 1 month. Light therapy is preferred over antidepressants in the treatment of SAD because it is a relatively safe and easy therapy with minimal side effects.[20] Two methods of light therapy, bright light and dawn simulation, have similar success rates in the treatment of SAD.[21]

It is possible that response to light therapy for SAD could be season dependent.[22] Morning therapy has provided the best results because light in the early morning aids in regulating the circadian rhythm.[20] People affected by SAD often have low energy, tend to eat more carbohydrates and sleep longer, but symptoms can vary between people.[23]

A Cochrane review conducted in 2019 states the evidence that light therapy's effectiveness as a treatment for the prevention of seasonal affective disorder is limited, although the risk of adverse effects are minimal. Therefore, the decision to use light therapy should be based on a person's preference of treatment.[24]

Non-seasonal depression

[edit]Light therapy has also been suggested in the treatment of non-seasonal depression and other psychiatric mood disturbances, including major depressive disorder,[25][26] bipolar disorder and postpartum depression.[27][28] A meta-analysis by the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that "for patients suffering from non-seasonal depression, light therapy offers modest though promising antidepressive efficacy."[29] A 2008 systematic review concluded that "overall, bright light therapy is an excellent candidate for inclusion into the therapeutic inventory available for the treatment of nonseasonal depression today, as adjuvant therapy to antidepressant medication, or eventually as stand-alone treatment for specific subgroups of depressed patients."[30] A 2015 review found that supporting evidence for light therapy was limited due to serious methodological flaws.[31]

A 2016 meta-analysis showed that bright light therapy appeared to be efficacious, particularly when administered for 2–5 weeks' duration and as monotherapy.[32]

Chronic circadian rhythm sleep disorders (CRSD)

[edit]In the management of circadian rhythm disorders such as delayed sleep phase disorder (DSPD), the timing of light exposure is critical. Light exposure administered to the eyes before or after the nadir of the core body temperature rhythm can affect the phase response curve.[33] Use upon awakening may also be effective for non-24-hour sleep–wake disorder.[34] Some users have reported success with lights that turn on shortly before awakening (dawn simulation). Evening use is recommended for people with advanced sleep phase disorder. Some, but not all, totally blind people whose retinae are intact, may benefit from light therapy.

Circadian rhythm sleep disorders and jet lag

[edit]Source:[35]

Situational CRSD

[edit]Light therapy has been tested for individuals with shift work sleep disorder and for jet lag.[36][37]

Sleep disorder in Parkinson's disease

[edit]Light therapy has been trialed in treating sleep disorders experienced by patients with Parkinson's disease.[38]

Sleep disorder in Alzheimer's disease

[edit]Studies have shown that daytime and evening light therapy for nursing home patients with Alzheimer's disease, who often struggle with agitation and fragmented wake/rest cycles effectively led to more consolidated sleep and an increase in circadian rhythm stability.[39][40][41]

Neonatal jaundice (postnatal jaundice)

[edit]

Light therapy is used to treat cases of neonatal jaundice.[42] Bilirubin, a yellow pigment normally formed in the liver during the breakdown of old red blood cells, cannot always be effectively cleared by a neonate's liver causing neonatal jaundice. Accumulation of excess bilirubin can cause central nervous system damage, and so this buildup of bilirubin must be treated. Phototherapy uses the energy from light to isomerize the bilirubin and consequently transform it into compounds that the newborn can excrete via urine and stools. Bilirubin is most successful absorbing light in the blue region of the visible light spectrum, which falls between 460 and 490 nm.[43] Therefore, light therapy technologies that utilize these blue wavelengths are the most successful at isomerizing bilirubin.[44]

Techniques

[edit]Photodynamic therapy

[edit]Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a form of phototherapy using nontoxic light-sensitive compounds (photosensitizers) that are exposed selectively to light at a controlled wavelength, laser intensity, and irradiation time, whereupon they generate toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) that target malignant and other diseased cells. Oxygen is thus required for activity, lowering efficacy in highly developed tumors and other hypoxic environments. Selective apoptosis of diseased cells is difficult due to the radical nature of ROS, but may be controlled for through membrane potential and other cell-type specific properties'[45] effects on permeability or through photoimmunotherapy. In developing any phototherapeutic agent, the phototoxicity of the treatment wavelength should be considered.

Photodynamic cancer therapy

[edit]Various cancer treatments utilizing PDT have been approved by the FDA. Treatments are available for actinic keratosis (blue light with aminolevulinic acid), cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, Barrett esophagus, basal cell skin cancer, esophageal cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and squamous cell skin cancer (Stage 0). Photosensitizing agents clinically-approved or undergoing clinical trials for the treatment of cancers include Photofrin, Temoporfin, Motexafin lutetium, Palladium bacteriopheophorbide, Purlytin, and Talaporfin. Verteporfin is approved to treat eye conditions such as macular degeneration, myopia, and ocular histoplasmosis.[46] Third-generation photosensitizers are currently in development, but none are yet approved for clinical trials.

Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy

[edit]PDT may also be utilized to treat multidrug-resistant skin, wound, or other superficial infections. This is known as antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) or photodynamic inactivation (PDI). aPDT has been observed to be effective against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Mycobacterium. aPDT has shown lowered efficacy on some other bacterial species, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii. This is likely due to factors such as cell wall thickness and membrane potential.[45] Many studies utilizing aPDT focus on the application of the photosensitizer through leakage from a hydrogel, which has been found to increase wound healing speed of skin infections[47][48] through the upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hypoxia inducible factor (HIF).[49] This controlled leakage allows for prolonged but limited generation of ROS, lowering the impact on human cell viability due to ROS cytotoxicity. It is unlikely for drug resistance to photosensitizers to form due to the nontoxic nature of the photosensitizer itself as well as the ROS generation mechanism of action, which cannot be prevented outside of hypoxic environments. Certain dental infections (peri-implantitis, periodontitis) are more difficult to treat with PDT as opposed to photothermal therapy due to the requirement of oxygen, though a significant response is still observed.[50][51][52]

Increased antimicrobial activity and wound healing speeds are typically observed when PDT is combined with photothermal therapy in photodynamic/photothermal combination therapy.

Photothermal Therapy

[edit]Photothermal therapy (PTT) is a form of phototherapy that uses non-toxic compounds called photothermal agents (PTA) that, when irradiated at a certain wavelength of light, converts the light energy directly to heat energy. The photothermal conversion efficiency determines the amount of light converted to heat, which can dictate the necessary irradiation time and/or laser intensity for treatments. Typically PTT treatments use wavelengths in the near-infrared (NIR) spectra, which can be further divided into NIR-I (760-900 nm), NIR-II (900-1880 nm), and NIR-III (2080-2340 nm) windows.[53] Wavelengths in these regions are typically less phototoxic than UV or high-energy visible light. In addition, NIR-II wavelengths have been observed to show deeper penetration than NIR-I wavelengths, allowing for treatment of deeper wounds, infections, and cancers. Important considerations for the development of a PTA include photothermal conversion efficiency, phototoxicity, laser intensity, irradiation time, and the temperature at which human cell viability is impaired (around 46-60 °C).[54] Currently, the only FDA-approved photothermal agent is indocyanine green which is active against both tumor and bacterial cells.[50][55]

PTT is less selective than photodynamic therapy (PDT, see above) due to its heat-based mechanism of action, but also less likely to promote drug resistance than most, if not all, currently developed treatments. In addition, PTT can be used in hypoxic environments and on deeper wounds, infections, and tumors than PDT due to the higher wavelength of light. Due to PTT activity in hypoxic environments, it may be also used on more developed tumors than PDT. Low-temperature PTT (≤ 45 °C) for treatment of infections is also a possibility when combined with an antibiotic compound due to heat's proportionality with membrane permeability - a hotter environment causes heightened membrane permeability, which thus allows the drug into the cell.[56] This would reduce/eliminate the impact on human cell viability, and aiding in antibiotic accumulation within the target cell may assist in restoring activity in antibiotics that pathogens had developed resistance to.

PTT is typically seen to have improved antimicrobial and wound healing activity when combined with an additional mechanism of action through PDT or added antibiotic compounds in the application.

Light boxes

[edit]

The production of the hormone melatonin, a sleep regulator, is inhibited by light and permitted by darkness as registered by photosensitive ganglion cells in the retina.[57] To some degree, the reverse is true for serotonin,[58] which has been linked to mood disorders. Hence, for the purpose of manipulating melatonin levels or timing, light boxes providing very specific types of artificial illumination to the retina of the eye are effective.[59]

Light therapy uses either a light box which emits up to 10,000 lux of light at a specified distance,[a] much brighter than a customary lamp, or a lower intensity of specific wavelengths of light from the blue (460 nm) to the green (525 nm) areas of the visible spectrum.[60] A 1995 study showed that green light therapy at doses of 350 lux produces melatonin suppression and phase shifts equivalent to 10,000 lux white light therapy,[61][62] but another study published in May 2010 suggests that the blue light often used for SAD treatment should perhaps be replaced by green or white illumination, because of a possible involvement of the cones in melatonin suppression.[63]

Risks and complications

[edit]Ultraviolet

[edit]Ultraviolet light causes progressive damage to human skin and erythema even from small doses.[64][65] This is mediated by genetic damage, collagen damage, as well as destruction of vitamin A and vitamin C in the skin and free radical generation.[citation needed] Ultraviolet light is also known to be a factor in formation of cataracts.[66][67] Ultraviolet radiation exposure is strongly linked to incidence of skin cancer.[68][64][69]

Visible light

[edit]Optical radiation of any kind with enough intensity can cause damage to the eyes and skin including photoconjunctivitis and photokeratitis.[70] Researchers have questioned whether limiting blue light exposure could reduce the risk of age-related macular degeneration.[71] According to the American Academy of Ophthalmology, there is no scientific evidence showing that exposure to blue light emitting devices result in eye damage.[72] According to Harriet Hall, blue light exposure is reported to suppress the production of melatonin, which affects our body's circadian rhythm and can decrease sleep quality.[73] It is reported that, in reproductive-age females, bright light therapy may activate the production of reproductive hormones, such as luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and estradiol[74]

Modern phototherapy lamps used in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder and sleep disorders either filter out or do not emit ultraviolet light and are considered safe and effective for the intended purpose, as long as photosensitizing drugs are not being taken at the same time and in the absence of any existing eye conditions. Light therapy is a mood altering treatment, and just as with drug treatments, there is a possibility of triggering a manic state from a depressive state, causing anxiety and other side effects. While these side effects are usually controllable, it is recommended that patients undertake light therapy under the supervision of an experienced clinician, rather than attempting to self-medicate.[75]

Contraindications to light therapy for seasonal affective disorder include conditions that might render the eyes more vulnerable to phototoxicity, tendency toward mania, photosensitive skin conditions, or use of a photosensitizing herb (such as St. John's wort) or medication.[76][77] Patients with porphyria should avoid most forms of light therapy. Patients on certain drugs such as methotrexate or chloroquine should use caution with light therapy as there is a chance that these drugs could cause porphyria.[citation needed]

Side effects of light therapy for sleep phase disorders include jumpiness or jitteriness, headache, eye irritation and nausea.[78] Some non-depressive physical complaints, such as poor vision and skin rash or irritation, may improve with light therapy.[79]

History

[edit]

Many ancient cultures practiced various forms of heliotherapy, including people of Ancient Greece, Ancient Egypt, and Ancient Rome.[81] The Inca, Assyrian and early Germanic peoples also worshipped the sun as a health bringing deity. Indian medical literature dating to 1500 BCE describes a treatment combining herbs with natural sunlight to treat non-pigmented skin areas. Buddhist literature from about 200 CE and 10th-century Chinese documents make similar references.

The Faroese physician Niels Finsen is believed to be the father of modern phototherapy. He developed the first artificial light source for this purpose.[82] Finsen used short wavelength light to treat lupus vulgaris, a skin infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. He thought that the beneficial effect was due to ultraviolet light killing the bacteria, but recent studies showed that his lens and filter system did not allow such short wavelengths to pass through, leading instead to the conclusion that light of approximately 400 nanometers generated reactive oxygen that would kill the bacteria.[83] Finsen also used red light to treat smallpox lesions. He received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1903.[84] Scientific evidence for some of his treatments is lacking, and later eradication of smallpox and development of antibiotics for tuberculosis rendered light therapy obsolete for these diseases.[85] In the early 20th-century light therapy was promoted by Auguste Rollier and John Harvey Kellogg.[86] In 1924, Caleb Saleeby founded The Sunlight League.[87]

From the late nineteenth century until the early 1930s, light therapy was considered an effective and mainstream medical therapy in the UK for conditions such as varicose ulcer, 'sickly children' and a wide range of other conditions. Controlled trials by the medical scientist Dora Colebrook, supported by the Medical Research Council, indicated that light therapy was not effective for such a wide range of conditions.[88]

Controversy

[edit]Red light therapy involves exposure to low levels of red light or near-infrared light, typically through lamps or masks.[89] It is promoted for various skin-related benefits, including improved appearance and reduced signed of aging.[89][90][91] However, there is currently insufficient scientific evidence to support many of these claims.[91] There has been some indication that it may reduce inflammation associated with conditions such as acne or rosacea, but evidence supporting its anti-aging effects remain limited.[89] Most existing research has focused on in-office treatments, while at-home devices are generally less powerful and precise, which may lead to inconsistent results.[89][90] It is generally considered safe, however if misused red light therapy could cause eye or skin damage.[92][89][91]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lux measures the amount of illumination in a square meter. The distance affects how much area the light is spread over.

- ^ Kalajian, T. A.; Aldoukhi, A.; Veronikis, A. J.; Persons, K.; Holick, M. F. (2017-09-13). "Ultraviolet B Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) Are More Efficient and Effective in Producing Vitamin D3 in Human Skin Compared to Natural Sunlight". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 11489. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-11362-2. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5597604. PMID 28904394.

- ^ "PUVA therapy for skin diseases: treatment features | Heliotherapy Research Institute". Retrieved 2022-06-01.

- ^ "Treating psoriasis: light therapy and phototherapy – National Psoriasis Foundation". Psoriasis.org. 2014-02-14. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ^ Titus S, Hodge J (October 2012). "Diagnosis and treatment of acne". Am Fam Physician. 86 (8): 734–740. PMID 23062156.

- ^ Pei S, Inamadar AC, Adya KA, Tsoukas MM (2015). "Light-based therapies in acne treatment". Indian Dermatol Online J. 6 (3): 145–157. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.156379. PMC 4439741. PMID 26009707.

- ^ Hession MT, Markova A, Graber EM (2015). "A review of hand-held, home-use cosmetic laser and light devices". Dermatol Surg. 41 (3): 307–320. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000283. PMID 25705949. S2CID 39722284.

- ^ Hamilton FL, Car J, Lyons C, Car M, Layton A, Majeed A (June 2009). "Laser and other light therapies for the treatment of acne vulgaris: systematic review". Br. J. Dermatol. 160 (6): 1273–1285. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09047.x. PMID 19239470. S2CID 6902995.

- ^ Patrizi, A; Raone, B; Ravaioli, GM (5 October 2015). "Management of atopic dermatitis: safety and efficacy of phototherapy". Clinical, Cosmetic and Investigational Dermatology. 8: 511–520. doi:10.2147/CCID.S87987. PMC 4599569. PMID 26491366.

- ^ "Phototherapy for Eczema: The Ultimate Guide to Using UV Light Therapy". skinsuperclear.com. 22 March 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ "Light Therapy". American Cancer Society. 14 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2015-02-12. Retrieved 2013-09-08.

- ^ Morton, C.A.; Brown, S.B.; Collins, S.; Ibbotson, S.; Jenkinson, H.; Kurwa, H.; Langmack, K.; Mckenna, K.; Moseley, H.; Pearse, A.D.; Stringer, M.; Taylor, D.K.; Wong, G.; Rhodes, L.E. (April 2002). "Guidelines for topical photodynamic therapy: report of a workshop of the British Photodermatology Group". British Journal of Dermatology. 146 (4): 552–567. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04719.x. PMID 11966684. S2CID 7137209.

- ^ Diffey BL (1980). "Ultraviolet radiation physics and the skin". Phys. Med. Biol. 25 (3): 405–426. Bibcode:1980PMB....25..405D. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/25/3/001. PMID 6996006. S2CID 250744277.

- ^ "What is Psoriasis: What Causes Psoriasis?". 29 January 2012. Archived from the original on 6 September 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ Bae, Jung Min; Jung, Han Mi; Hong, Bo Young; Lee, Joo Hee; Choi, Won Joon; Lee, Ji Hae; Kim, Gyong Moon (1 July 2017). "Phototherapy for Vitiligo". JAMA Dermatology. 153 (7): 666–674. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0002. PMC 5817459. PMID 28355423.

- ^ Baron ED, Stevens SR (2003). "Phototherapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma". Dermatologic Therapy. 16 (4): 303–310. doi:10.1111/j.1396-0296.2003.01642.x. PMID 14686973. S2CID 33047908.

- ^ Bandow, Grace D.; Koo, John Y. M. (August 2004). "Narrow-band ultraviolet B radiation: a review of the current literature". International Journal of Dermatology. 43 (8): 555–561. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02032.x. PMID 15304175. S2CID 27388121.

- ^ Arden, G. B.; Sivaprasad, S. (2012-02-03). "The pathogenesis of early retinal changes of diabetic retinopathy". Documenta Ophthalmologica. 124 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1007/s10633-011-9305-y. ISSN 0012-4486. PMID 22302291. S2CID 25514638.

- ^ Sivaprasad S, Arden G (2016). "Spare the rods and spoil the retina: revisited". Eye (Lond) (Review). 30 (2): 189–192. doi:10.1038/eye.2015.254. PMC 4763134. PMID 26656085.

- ^ "Light Therapy – Topic Overview". WebMD. 30 June 2009. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ a b Sanassi Lorraine A (2014). "Seasonal affective disorder: Is there light at the end of the tunnel?". Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 27 (2): 18–22. doi:10.1097/01.jaa.0000442698.03223.f3. PMID 24394440. S2CID 45234549.

- ^ Danilenko, K.V.; Ivanova, I.A. (July 2015). "Dawn simulation vs. bright light in seasonal affective disorder: Treatment effects and subjective preference". Journal of Affective Disorders. 180: 87–89. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.055. PMID 25885065.

- ^ Thompson C, Stinson D, Smith A (September 1990). "Seasonal affective disorder and season-dependent abnormalities of melatonin suppression by light". Lancet. 336 (8717): 703–706. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(90)92202-S. PMID 1975891. S2CID 34280446.

- ^ Doyle, Ashley. "Light Therapy: Does It Work and Can It Help You?". Savvysleeper. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- ^ Nussbaumer-Streit, Barbara; Forneris, Catherine A.; Morgan, Laura C.; Van Noord, Megan G.; Gaynes, Bradley N.; Greenblatt, Amy; Wipplinger, Jörg; Lux, Linda J.; Winkler, Dietmar; Gartlehner, Gerald (2019). "Light therapy for preventing seasonal affective disorder". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (4) CD011269. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011269.pub3. PMC 6422319. PMID 30883670.

- ^ Benedetti, Francesco; Colombo, Cristina; Pontiggia, Adriana; Bernasconi, Alessandro; Florita, Marcello; Smeraldi, Enrico (June 2003). "Morning light treatment hastens the antidepressant effect of citalopram: a placebo-controlled trial". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 64 (6): 648–653. doi:10.4088/JCP.v64n0605. PMID 12823078. S2CID 40483934.

- ^ Tuunainen, Arja; Kripke, Daniel F; Endo, Takuro (2004-04-19). "Light therapy for non-seasonal depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004 (2) CD004050. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004050.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6669243. PMID 15106233.

- ^ Prasko J (November 2008). "Bright light therapy". Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 29 (Suppl 1): 33–64. PMID 19029878.

- ^ Terman M (December 2007). "Evolving applications of light therapy". Sleep Med Rev. 11 (6): 497–507. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2007.06.003. PMID 17964200. S2CID 2054580.

- ^ Tuunainen, Arja; Kripke, Daniel F; Endo, Takuro (19 April 2004). "Light therapy for non-seasonal depression". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004 (2) CD004050. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004050.pub2. PMC 6669243. PMID 15106233.

- ^ Even, C; Schröder, CM; Friedman, S; Rouillon, F (2008). "Efficacy of light therapy in nonseasonal depression: A systematic review". Journal of Affective Disorders. 108 (1–2): 11–23. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2007.09.008. PMID 17950467.

- ^ Mårtensson B; Pettersson A; Berglund L; Ekselius L (2015). "Bright white light therapy in depression: A critical review of the evidence". J Affect Disord. 182: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.04.013. PMID 25942575.

- ^ Al-Karawi D, Jubair L (Jul 2016). "Bright light therapy for nonseasonal depression: Meta-analysis of clinical trials". J Affect Disord. 198: 64–71. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.016. PMID 27011361.

- ^ Bjorvatn, Bjørn; Pallesen, Ståle (February 2009). "A practical approach to circadian rhythm sleep disorders". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 13 (1): 47–60. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2008.04.009. PMID 18845459.

- ^ Zisapel, Nava (2001). "Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders". CNS Drugs. 15 (4): 311–328. doi:10.2165/00023210-200115040-00005. PMID 11463135. S2CID 34990596.

- ^ Dodson, Ehren R.; Zee, Phyllis C (December 2010). "Therapeutics for Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders". Sleep Medicine Clinics. 5 (4): 701–715. doi:10.1016/j.jsmc.2010.08.001. ISSN 1556-407X. PMC 3020104. PMID 21243069.

- ^ Brown GM, Pandi-Perumal SR, Trakht I, Cardinali DP (March 2009). "Melatonin and its relevance to jet lag". Travel Med Infect Dis. 7 (2): 69–81. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2008.09.004. PMID 19237140.

- ^ Crowley, S.J.; Eastman, C.I. (2013). "Light and Melatonin Treatment for Jet Lag Disorder". Encyclopedia of Sleep. pp. 74–80. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-378610-4.00285-0. ISBN 978-0-12-378611-1.

- ^ Willis G. L.; Moore C.; Armstrong S. M. (2012). "A historical justification for and retrospective analysis of the systematic application of light therapy in Parkinson's disease". Reviews in the Neurosciences. 23 (2): 199–226. doi:10.1515/revneuro-2011-0072. PMID 22499678. S2CID 37717110.

- ^ Satlin, A.; Volicer, L.; Ross, V.; Herz, L.; Campbell, S. (August 1992). "Bright light treatment of behavioral and sleep disturbances in patients with Alzheimer's disease". American Journal of Psychiatry. 149 (8): 1028–1032. doi:10.1176/ajp.149.8.1028. PMID 1353313.

- ^ Ancoli-Israel, Sonia; Gehrman, Philip; Martin, Jennifer L.; Shochat, Tamar; Marler, Matthew; Corey-Bloom, Jody; Levi, Leah (February 2003). "Increased Light Exposure Consolidates Sleep and Strengthens Circadian Rhythms in Severe Alzheimer's Disease Patients". Behavioral Sleep Medicine. 1 (1): 22–36. doi:10.1207/s15402010bsm0101_4. PMID 15600135. S2CID 39597697.

- ^ Hanford, Nicholas; Figueiro, Mariana (21 January 2013). "Light Therapy and Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementia: Past, Present, and Future". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 33 (4): 913–922. doi:10.3233/jad-2012-121645. PMC 3553247. PMID 23099814.

- ^ Newman TB, Kuzniewicz MW, Liljestrand P, Wi S, McCulloch C, Escobar GJ (May 2009). "Numbers needed to treat with phototherapy according to American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines". Pediatrics. 123 (5): 1352–1359. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-1635. PMC 2843697. PMID 19403502.

- ^ Grossweiner, Leonard I.; Grossweiner, James B.; Gerald Rogers, B. H. (2005). "Phototherapy of Neonatal Jaundice" (PDF). The Science of Phototherapy: An Introduction. pp. 329–335. doi:10.1007/1-4020-2885-7_13. ISBN 978-1-4020-2883-0.

- ^ "Phototherapy in neonatal jaundice". BMJ. 2 (5805): 62–63. 8 April 1972. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5805.62-a. S2CID 43085146.

- ^ a b Nie, Xiaolin; Jiang, Chenyu; Wu, Shuanglin; Chen, Wangbingfei; Lv, Pengfei; Wang, Qingqing; Liu, Jingyan; Narh, Christopher; Cao, Xiuming; Ghiladi, Reza A.; Wei, Qufu (2020). "Carbon quantum dots: A bright future as photosensitizers for in vitro antibacterial photodynamic inactivation". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology. 206 111864. Bibcode:2020JPPB..20611864N. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2020.111864. PMID 32247250. S2CID 214794593.

- ^ Baskaran, Rengarajan; Lee, Junghan; Yang, Su-Geun (2018). "Clinical development of photodynamic agents and therapeutic applications". Biomaterials Research. 22 25. doi:10.1186/s40824-018-0140-z. ISSN 1226-4601. PMC 6158913. PMID 30275968.

- ^ Xu, Yinglin; Chen, Haolin; Fang, Yifen; Wu, Jun (2022). "Hydrogel Combined with Phototherapy in Wound Healing". Advanced Healthcare Materials. 11 (16) 2200494. doi:10.1002/adhm.202200494. ISSN 2192-2640. PMID 35751637. S2CID 250021788.

- ^ Ding, Qiuyue; Sun, Tingfang; Su, Weijie; Jing, Xirui; Ye, Bing; Su, Yanlin; Zeng, Lian; Qu, Yanzhen; Yang, Xu; Wu, Yuzhou; Luo, Zhiqiang; Guo, Xiaodong (2022). "Bioinspired Multifunctional Black Phosphorus Hydrogel with Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties: A Stepwise Countermeasure for Diabetic Skin Wound Healing". Advanced Healthcare Materials. 11 (12) 2102791. doi:10.1002/adhm.202102791. ISSN 2192-2640. PMID 35182097. S2CID 246974402.

- ^ Zhang, Xingyu; Zhang, Guannan; Zhang, Hongyu; Liu, Xiaoping; Shi, Jing; Shi, Huixian; Yao, Xiaohong; Chu, Paul K.; Zhang, Xiangyu (2020). "A bifunctional hydrogel incorporated with CuS@MoS2 microspheres for disinfection and improved wound healing". Chemical Engineering Journal. 382 122849. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2019.122849. S2CID 203938686.

- ^ a b Shim, Sang Ho; Lee, Si Young; Lee, Jong-Bin; Chang, Beom-Seok; Lee, Jae-Kwan; Um, Heung-Sik (2022). "Antimicrobial photothermal therapy using diode laser with indocyanine green on Streptococcus gordonii biofilm attached to zirconia surface". Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy. 38 102767. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2022.102767. PMID 35182778. S2CID 246926124.

- ^ Böcher, Sarah; Wenzler, Johannes-Simon; Falk, Wolfgang; Braun, Andreas (2019). "Comparison of different laser-based photochemical systems for periodontal treatment". Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy. 27: 433–439. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.06.009. PMID 31319164. S2CID 197663815.

- ^ Fekrazad, Reza; Khoei, Farzaneh; Bahador, Abbas; Hakimiha, Neda (2020). "Comparison of different modes of photo-activated disinfection against Porphyromonas gingivalis: An in vitro study". Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy. 32 101951. doi:10.1016/j.pdpdt.2020.101951. PMID 32818643. S2CID 221221714.

- ^ Feng, Zhe; Tang, Tao; Wu, Tianxiang; Yu, Xiaoming; Zhang, Yuhuang; Wang, Meng; Zheng, Junyan; Ying, Yanyun; Chen, Siyi; Zhou, Jing; Fan, Xiaoxiao; Zhang, Dan; Li, Shengliang; Zhang, Mingxi; Qian, Jun (2021-09-24). "Perfecting and extending the near-infrared imaging window". Light: Science & Applications. 10 (1): 197. Bibcode:2021LSA....10..197F. doi:10.1038/s41377-021-00628-0. ISSN 2047-7538. PMC 8463572. PMID 34561416.

- ^ Leber, Bettina; Mayrhauser, Ursula; Leopold, Barbara; Koestenbauer, Sonja; Tscheliessnigg, Karlheinz; Stadlbauer, Vanessa; Stiegler, Philipp (2012). "Impact of temperature on cell death in a cell-culture model of hepatocellular carcinoma". Anticancer Research. 32 (3): 915–921. ISSN 1791-7530. PMID 22399612.

- ^ Li, Xingde; Beauvoit, Bertrand; White, Renita; Nioka, Shoko; Chance, Britton; Yodh, Arjun G. (1995-05-30). Chance, Britton; Alfano, Robert R. (eds.). "Tumor localization using fluorescence of indocyanine green (ICG) in rat models". Optical Tomography, Photon Migration, and Spectroscopy of Tissue and Model Media: Theory, Human Studies, and Instrumentation. 2389. SPIE: 789–797. Bibcode:1995SPIE.2389..789L. doi:10.1117/12.210021. S2CID 93116083.

- ^ Blicher, Andreas; Wodzinska, Katarzyna; Fidorra, Matthias; Winterhalter, Mathias; Heimburg, Thomas (2009-06-03). "The Temperature Dependence of Lipid Membrane Permeability, its Quantized Nature, and the Influence of Anesthetics". Biophysical Journal. 96 (11): 4581–4591. arXiv:0807.4825. Bibcode:2009BpJ....96.4581B. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.062. ISSN 0006-3495. PMC 2711498. PMID 19486680.

- ^ Lazzerini Ospri, Lorenzo; Prusky, Glen; Hattar, Samer (25 July 2017). "Mood, the Circadian System, and Melanopsin Retinal Ganglion Cells". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 40 (1): 539–556. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-072116-031324. PMC 5654534. PMID 28525301.

- ^ Harrison, S. J.; Tyrer, A. E.; Levitan, R. D.; Xu, X.; Houle, S.; Wilson, A. A.; Nobrega, J. N.; Rusjan, P. M.; Meyer, J. H. (November 2015). "Light therapy and serotonin transporter binding in the anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortex". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 132 (5): 379–388. doi:10.1111/acps.12424. PMC 4942271. PMID 25891484.

- ^ Wu, Mann-Chian; Sung, Huei-Chuan; Lee, Wen-Li; Smith, Graeme D (October 2015). "The effects of light therapy on depression and sleep disruption in older adults in a long-term care facility". International Journal of Nursing Practice. 21 (5): 653–659. doi:10.1111/ijn.12307. PMID 24750268.

- ^ Wright HR, Lack LC, Kennaway DJ (March 2004). "Differential effects of light wavelength in phase advancing the melatonin rhythm". J. Pineal Res. 36 (2): 140–44. doi:10.1046/j.1600-079X.2003.00108.x. PMID 14962066. S2CID 400498.

- ^ Saeeduddin Ahmed; Neil L Cutter; Alfred J. Lewy; Vance K. Bauer; Robert L Sack; Mary S. Cardoza (1995). "Phase Response Curve of Low-Intensity Green Light in Winter Depressives". Sleep Research. 24: 508. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-5-42. PMC 1309618. PMID 16283926.

The magnitude of the phase shifts [using low-level green light therapy] are comparable to those obtained using high-intensity white light in winter-depressives.

- ^ Michel A. Paul; James C. Miller; Gary Gray; Fred Buick; Sofi Blazeski; Josephine Arendt (July 2007). "Circadian Phase Delay Induced by Phototherapeutic Devices". Sleep Research. 78 (7): 645–52.

- ^ J.J. Gooley; S.M.W. Rajaratnam; G.C. Brainard; R.E. Kronauer; C.A. Czeisler; S.W. Lockley (May 2010). "Spectral Responses of the Human Circadian System Depend on the Irradiance and Duration of Exposure to Light". Science Translational Medicine. 2 (31): 31–33. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3000741. PMC 4414925. PMID 20463367.

- ^ a b Matsumura, Yasuhiro; Ananthaswamy, Honnavara N (March 2004). "Toxic effects of ultraviolet radiation on the skin". Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 195 (3): 298–308. Bibcode:2004ToxAP.195..298M. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2003.08.019. PMID 15020192.

- ^ Barkham (5 June 2012). "One face, but two sides of a story". Theguardian.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ Yam, Jason C. S.; Kwok, Alvin K. H. (31 May 2013). "Ultraviolet light and ocular diseases". International Ophthalmology. 34 (2): 383–400. doi:10.1007/s10792-013-9791-x. PMID 23722672. S2CID 33503388.

- ^ International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation, Protection. (August 2004). "Guidelines on limits of exposure to ultraviolet radiation of wavelengths between 180 nm and 400 nm (incoherent optical radiation)". Health Physics. 87 (2): 171–86. Bibcode:2004HeaPh..87..171.. doi:10.1097/00004032-200408000-00006. PMID 15257218. S2CID 34605136.

- ^ Ichihashi, M.; Ueda, M.; Budiyanto, A.; Bito, T.; Oka, M.; Fukunaga, M.; Tsuru, K.; Horikawa, T. (July 2003). "UV-induced skin damage". Toxicology. 189 (1–2): 21–39. Bibcode:2003Toxgy.189...21I. doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(03)00150-1. PMID 12821280.

- ^ Epstein, Franklin H.; Gilchrest, Barbara A.; Eller, Mark S.; Geller, Alan C.; Yaar, Mina (29 April 1999). "The Pathogenesis of Melanoma Induced by Ultraviolet Radiation". New England Journal of Medicine. 340 (17): 1341–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM199904293401707. PMID 10219070.

- ^ European Commission; Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion (2011), Non-binding guide to good practice for implementing Directive 2006/25/EC 'artificial optical radiation', doi:10.2767/74218, ISBN 978-92-79-16046-2

- ^ Glazer-Hockstein C, Dunaief JL (January 2006). "Could blue light-blocking lenses decrease the risk of age-related macular degeneration?". Retina. 26 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1097/00006982-200601000-00001. PMID 16395131. S2CID 29045585.

- ^ American Academy of Ophthalmology. "Should You Be Worried About Blue Light?". American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Hall, Harriet (December 2020). "Blue light". Science-based Medicine. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Danilenko KV, Samoilova EA (2007). "Stimulatory effect of morning bright light on reproductive hormones and ovulation: results of a controlled crossover trial". PLOS Clinical Trials. 2 (2) e7. doi:10.1371/journal.pctr.0020007. PMC 1851732. PMID 17290302.

- ^ Terman M, Terman JS (August 2005). "Light therapy for seasonal and nonseasonal depression: efficacy, protocol, safety, and side effects". CNS Spectr. 10 (8): 647–63, quiz 672. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.527.6947. doi:10.1017/S1092852900019611. PMID 16041296. S2CID 27002316.

- ^ Gagarina, AK (2007-12-08). "Light Therapy Diagnostic Indications and Contraindications". American Medical Network. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ^ Westrin, Åsa; Lam, Raymond W. (October 2007). "Seasonal Affective Disorder: A Clinical Update". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 19 (4): 239–246. doi:10.1080/10401230701653476. PMID 18058281.

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff (20 March 2013). "Light Therapy. Tests and Procedures. Risks". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Roger DR (2007-12-04). "Practical aspects of light therapy". American Medical Network. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ^ Woloshyn, Tania Anne (2017). "Consuming light". Soaking Up the Rays: Light Therapy and Visual Culture in Britain, C. 1890-1940. Manchester: Manchester University Press. doi:10.7765/9781526115980. ISBN 978-1-5261-1598-0.

- ^ F. Ellinger Medical Radiation Biology Springfield 1957

- ^ Ingold, Niklaus (2015). Lichtduschen Geschichte einer Gesundheitstechnik, 1890–1975 (in German). Chronos Verlag. pp. 40–49. hdl:20.500.12657/31817. ISBN 978-3-0340-1276-8.

- ^ Moller, Kirsten Iversen; Kongshoj, Brian; Philipsen, Peter Alshede; Thomsen, Vibeke Ostergaard; Wulf, Hans Christian (2014-11-12). "How Finsen's light cured lupus vulgaris". Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 21 (3): 118–24. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2005.00159.x. PMID 15888127. S2CID 23272350.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1903". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. 2016-11-01. Archived from the original on 2016-10-22. Retrieved 2016-11-01.

- ^ "Engines of our Ingenuity No. 1769: NIELS FINSEN". Retrieved 2014-04-05.

- ^ Loignon, Austin E. (2022). "Bringing Light to the World: John Harvey Kellogg and Transatlantic Light Therapy". Journal of Transatlantic Studies. 20 (1): 103–128. doi:10.1057/s42738-022-00092-7. PMC 8819196. S2CID 246636998.

- ^ Butler, A. R; Greenhalgh, I. (2017). "Sanatoria revisited: sunlight and health" (PDF). J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 47 (3): 276–80. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2017.314. PMID 29465107. S2CID 3403283.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Edwards, Martin (2011). "Dora Colebrook and the evaluation of light therapy". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 104 (2). Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and Minervation Ltd: 84–6. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k067. PMC 3031646. PMID 21282799. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Katzel, Taylor (February 20, 2025). "Does red light therapy work? Experts weigh in on TikTok skincare trend". CBC Kids News.

- ^ a b Matei, Adrienne (2024-09-25). "Does red light therapy work? These are the benefits and drawbacks". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2025-04-23.

- ^ a b c "Red Light Therapy". Cleveland Clinic. December 1, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2025.

- ^ Armitage, Hanae (February 24, 2025). "What's the deal with red light therapy?". Scope. Stanford Medicine.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Phototherapy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Phototherapy at Wikimedia Commons